Abstract

Purpose of review:

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been extensively studied for therapeutic application in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Despite their promise, recent findings suggest that MSC replication during repair process may lead to replicative senescence and stem cell exhaustion. Here, we review the basic mechanisms of MSC senescence, how it leads to degenerative diseases, and potential treatments for such diseases.

Recent findings:

Emerging evidence has shown a link between senescent MSCs and degenerative diseases, especially age-related diseases such as osteoarthritis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. During these disease processes, MSCs undergo cell senescence and mediate Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotypes (SASP) to affect the surrounding microenvironment. Thus, senescent MSCs can accelerate tissue aging by increasing the number of senescent cells and spreading inflammation to neighboring cells.

Summary:

Senescent MSCs not only hamper tissue repair through cell senescence associated stem cell exhaustion, but also mediate tissue degeneration by initiating and spreading senescence-associated inflammation. It suggests new strategies of MSC-based cell therapy to remove, rejuvenate, or replace (3Rs) the senescent MSCs.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Cell senescence, Replication stress, Age-associated diseases, Senolytics, Osteoarthritis

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) are tissue-specific progenitor cells with self-renewal abilities and multi-potent differentiation potentials, which make them one of the key players in maintaining tissue and organ homeostasis [1]. MSCs can be found in a variety of tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, cartilage, dental pulp, umbilical cord blood, and placenta [1]. Thus they can differentiate into multiple cell lineages, such as bone, cartilage, adipose, and neuron cells [1]. Due to their easy isolation and expansion, MSCs have shown increasing promise for clinical application [1].

In the last few years, MSCs have emerged as powerful tools in their use as seed cells for therapeutic applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine [2]. Due to their low immunogenicity, MSCs can be safely transplanted autologously or allogeneically [3]. They have been applied to the treatment of different diseases, such as graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD), diabetes mellitus (DM), Crohn’s disease (CD), multiple sclerosis (MS), myocardial infarction (MI), etc [2]. Despite the huge advances made in the field, a critical limitation still greatly restricts the development of cell-based therapy using MSCs. Due to the low abundances in somatic tissues, MSCs usually require ex-vivo expansion before their therapeutic administration. However, MSCs inevitably reach a senescent phenotype after prolonged expansion [4] [5]. This is caused by stem cell exhaustion during cellular replication, either through cell expansion in vitro or repairing a large and chronic tissue wound in vivo. In addition, tissue aging reduces DNA synthesis and repair efficiency, accumulates DNA damage, impairs stem cell function, and drives cell senescence [6]. Thus, it is of great importance to understand the impact of senescent MSCs on their biological functions and their contribution to MSC-related diseases.

Emerging evidence has shown that senescent MSCs derived from various tissues play degenerative roles during tissue repair due to changes that occur with cell senescence. Thus they often contribute to the progression or pathogenesis of age-associated diseases. Current treatments can be summarized into the 3Rs strategy: remove, rejuvenate, and replace. In this review, we will discuss in details the current knowledge about mechanisms of MSC senescence, the roles of senescent MSCs in different diseases, and potential therapies to prevent and treat senescent MSC-associated diseases.

MSC SENESCENCE

Stem cell senescence is a cellular response to endogenous or exogenous stresses that limit proliferation and functions [6]. Cellular senescence is often considered a hallmark of aging. MSC senescence can occur from various stimuli, including oxidative stress, irradiation, chemicals, or replicative exhaustion. It has been shown that senescent cells accumulate in aged tissue [6] and contribute to the pathogenesis of age-associated diseases. This is due to the inherent property of adult somatic cells having a limited number of divisions, which eventually leads to a state of replicative senescence [7].

Senescent MSCs have many prominent features. First, senescent MSCs show an enlarged and more granular morphology. They have a decrease of cell colony number (CFU), which is one of the indicators of cellular senescence. MSCs also increase the expression of SA-β-gal due to increased lysosomal activities and altered cytosolic pH [8]. Second, the nuclei of senescent MSCs exhibit small and condensed spots of heterochromatin structure, which is called senescence-associated heterochromatic foci (SAHF) [9]. Third, there is a change in epigenetic regulation in senescent MSCs. The most promising epigenetic marker to predict MSC senescence is DNA methylation [10]. Age-associated hypomethylation interferes with transcription factors and affects gene expression. Fourth, senescent MSCs have shortened telomeres, which is a key characteristic of cellular senescence and aging. With each replication cycle, telomere shortening occurs in MSCs until it reaches a critical length that induces cellular senescence. Last, senescent MSCs tend to change their differentiation potentials. It is known that MSCs have differentiation potential for both osteogenesis and adipogenesis. However some senescent MSCS are more likely to differentiate toward adipogenesis than osteogenesis [11]. On the other hand, senescent MSCs of human osteoarthritic cartilage are prone to osteogenesis rather than chondrogenesis, even under chondrogenic induction conditions [12].

Senescent MSCs do not act on themselves only. They tend to affect their neighboring cells through paracrine mechanisms. This is also known as a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Senescent MSCs secrete SASP factors including interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-8, matrix metalloproteinase1 (MMP1), TNF-α, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [13]. Cellular senescence significantly increases the levels of SASP released. Due to the fact that MSCs produce a broad spectrum of secretory factors such as cytokines and growth factors, senescent MSCs are also responsible for inflammation that contributes to age-associated phenotypes [14].

Another way for senescent MSCs to influence their microenvironment is through their secretome. Microvesicles (MVs) are a key component of the cell secretome. They function in immunomodulatory regulation and tumor growth inhibition [15] [16]. One of the well-studied MVs is MSCs-derived exosomes. These exosomes contain biological active molecules from the MSCs, such as cytokines, growth factors, and regulatory miRNA [17]. It has been shown that senescent MSCs change the composition of the exosomes, especially the content of miRNA. RNAseq analysis indicated that many highly expressed genes in senescent MSC MVs are associated with aging-related diseases [18].

DIFFERENT TYPES OF MSC SENESCENCE

Cell senescence can be triggered after cells undergo multiple rounds of divisions. This is termed replicative senescence [7]. Although MSCs have a strong ability to proliferate and self-renew, they are not immune to senescence. Replicative senescence is a common cause for MSC senescence after MSC is activated to undergo cell divisions during the tissue repair process. Senescence is an irreversible process caused by telomere erosion after a number of cell divisions. Replicative senescence can cause long-term alterations to phenotype including inflammation, differentiation potentials, gene expression, and epigenetic profiles. Since this process is a continuous and dynamic change, replicative senescence poses the most difficult challenge for MSCs in therapeutic applications.

However, replicative senescence is not the only way for MSC to become senescent. Oncogene-induced senescence is caused by the activation or overexpression of oncogenes. Oncogene activation is associated with tumorigenesis, while oncogene-induced senescence causes genetic stress and growth arrest. Stress-induced premature senescence occurs due to different stimuli including reactive oxygen species (ROS), radiation, osmotic stress, high glucose concentrations, mechanical stress, hypoxia, and heat shock [19] [20]. In contrast, developmental senescence refers to senescence that occurs as a part of normal cellular development, which is induced by pluripotent genes in non-pathological states. This process is regulated by three canonical aging signaling pathways, insulin-like growth factor, rapamycin/mTOR, and Sirtuins/NAD+ pathways [21] [22] [23].

SENESCENT MSCS IN DISEASES

Although mostly known for their self-renew ability and differentiation potentials, increasing evidence has shown that senescent MSCs play a degenerative role in many diseases, especially age-associated diseases. Understanding the negative roles of senescent MSCs in tissue repair and regeneration will benefit the future research to develop therapeutic applications for intervention. As described in the following, senescent MSCs have been shown to associate with or contribute to the phenotypes and progression of different diseases.

Cartilage-derived MSCs

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic disease that includes changes such as articular cartilage degradation, osteophyte formation and subchondral bone sclerosis [36] [37]. Adult articular cartilage contains a small population of MSCs. Although it has been identified for more than ten years [38] [39] [40], relatively little research has been done on cartilage-derived MSCs due to the challenge of obtaining adequate number of cells. Recent studies have shown that there are more MSCs in OA cartilage than normal cartilage [41] [42]. These OA-MSCs often existed in clusters in human cartilage, which is a hallmark of OA due to cell replication. Chen group was able to successfully isolate cell lines from OA patients [43]. The heterogeneous OA-MSCs can be grouped into two populations. While the less senescent (higher CPU) cell population prefers to undergo chondrogenesis, the more senescent (lower CPU) cell population prefers to undergo osteogenesis. OA-MSCs expressed higher levels of hypertrophic OA cartilage markers, such as COL10A1 and RUNX2. The induction of chondrogenesis further stimulated expression of COL10A1 and MMP13 in these OA cartilage derived MSCs [12]. This suggests that OA-MSCs contribute to the OA phenotype and may possibly drive pathogenesis of cartilage hypertrophy, ossification, and degeneration.

Bone marrow-derived MSCs

Bone marrow MSCs is the most extensively investigated MSCs. Brondello group tested senescent MSCs from synovial tissue and sub-chondral bone marrow in relation to OA development [44]. When incubated with a senescence-promoting DNA-damage inducer, human bone marrow-derived MSCs showed an increase in SA-β-gal cells and impaired self-renewal ability. When injected intra-articularly to wild-type mice, senescent MSCs were sufficient to induce cartilage degeneration. These data suggest senescent MSCs contribute to OA development.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic lung disease with a progressive and irreversible loss of lung function [45]. Aging is considered the main risk factor for IPF. There is an increase in cell senescence markers in lung fibroblasts from IPF patients. In animal models, aged bone marrow-derived MSCs have decreased protective activity. Rojas group characterized MSCs from IPF patients and found an increase in cell senescence, which was associated with increased DNA damage and SASPs [46]. These bone marrow-derived MSCs from IPF patients have fragmented and dysfunctional mitochondria. Human lung fibroblasts were cultured with IPF MSCs and resulted in increased expression of senescence markers, including SA-β-gal, p16INK4A and p53. These results suggest a link between senescent MSCs and the onset of the IPF disease.

Adipose-derived MSCs

Physical dysfunction is associated with aging. Senescent cells lead to tissue degeneration and contribute to phenotypes such as disability, increased health problems, and mortality. Kirkland group demonstrated that transplanting senescent adipose-derived MSCs into young mice caused physical dysfunction [47]. The visceral adipose tissue has more SA-β-gal cells and increased p16INK4A expression. The mice exhibited early walking disability and accelerated aging. Thus, a small number of transplanted senescent MSCs can affect normal cells to cause long lasting and degenerative effects.

Cardiac Progenitor Cells

Human heart is known to harbor a group of self-renewal multi-potent cardiac stem and progenitor cells (CPCs) [48]. Function and potency of CPCs are decreased by aging, which can lead to cardiovascular disease [49]. Ellison-Hughes group studied CPCs isolated from patients with cardiovascular disease [50]. Analysis showed an accumulation of senescent CPCs with diminished self-renewal, differentiation and regenerative potentials. These senescent CPCs showed increased expression of SASPs, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MMP-3, PAI1, and GM-CSF. Through secreting these SASPs, senescent CPCs could negatively impact surrounding cells and make normal CPCs lose proliferative capacity and enter senescence.

Neural Progenitor Cells

It has been shown recently that neural progenitor cells may play important roles in neuro-degenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s. Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) are capable of differentiating into neuronal and glial cell types. Crocker group has identified senescent NPCs from primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) [51]. These senescent NPCs reside within demyelinated white matter lesions, expressing senescence markers. They also secrete extracellular HMGB1, a protein associated with cellular senescence, which changes gene expression and impairs maturation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs). When incubated with conditioned medium from PPMS NPCs, OPCs showed an increase in senescence markers, such as MMP2, p16INK4A, and IGFBP2. Based on the data, they hypothesize that senescent NPCs impairs the regenerative potentials through affecting the microenvironment. Thus, senescent NPCs within the multiple sclerosis brain contribute to chronic demyelination and cause aberrant cellular aging.

MECHANISMS OF MSC SENESCENCE

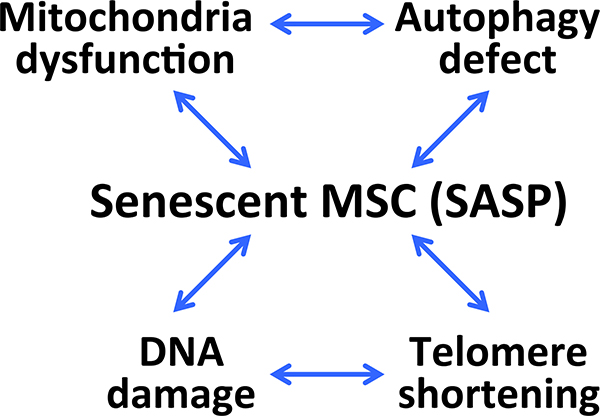

There are different mechanisms to cause MSCs to become senescent, including DNA damage, telomere erosion, mitochondrial dysfunction, and autophagy defects[2]. Although most of them are associated with aging process, they rarely occur alone and are often closely interrelated to regulate stem cell senescence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of MSC senescence. The key factors leading to MSC senescence include mitochondria dysfunction, autophagy defect, DNA damage, and telomere shortening. One prominent feature of senescent MSC is SASP (Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotypes). Through its SASP-dependent inflammatory signaling, senescent MSC exerts its effect on tissue degeneration and initiation of aging-associated diseases.

DNA damage

DNA damage is a source for initiating cell senescence. Since cell genome is critical genetic material of an organism, disruption of DNA stability often accelerates cell senescence and death, or even results in cancer and tumors. During the proliferation process, MSCs are prone to DNA damage [24]. It is termed as replication stress [25]. Another main cause for DNA damage and aging is oxidative stress. MSC senescence is also closely related to reactive oxygen species (ROS). The increase in intracellular ROS can reduce DNA synthesis and cell proliferation and cause senescence of bone marrow MSCs [26]. Senescent MSCs also increase production of ROS, which in turn impairs proliferation and differentiation of MSCs [27].

Telomere erosion

Telomere erosion is one of the prominent features of MSCs during cellular aging. The telomere is a special structure located at the end of the chromosomes, which is gradually shortened with every DNA replication. When the telomere shortens to a degree where chromosome stability is affected and DNA replication cannot continue, MSCs will go into cell senescence [28]. Telomere disorders play a role in diseases such as congenital dyskeratosis. Bone marrow-derived MSCs from congenital dyskeratosis showed a change of differentiation potential into adipocytes and fibroblasts, and exhibited features of cell senescence [29].

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another key factor in MSC senescence. Mitochondria are energy production centers in cells, which are essential for cellular respiration and proliferation. Under normal conditions, mitophagy is responsible for clearing out dysfunctional mitochondria. Accumulation of defective mitochondria will eventually lead to cell senescence or death. Senescent MSCs have disturbed mitochondrial dynamics that affect their cell morphology and decrease the levels of mitophagy [30]. A main cause for mitochondrial dysfunction is the accumulation of ROS. Defective mitochondria produce more ROS, and this accumulation of ROS leads to MSC senescence [31].

Autophagy defect

Autophagy defect is also a mechanism for causing MSC senescence. Autophagy is a highly conserved process for maintaining homeostasis through molecular degradation and organelle turnover [32] [33]. Autophagy is necessary for MSC proliferation and differentiation, while lack of autophagy leads to loss of stem cell function and dysregulated cell proliferation [34]. As a part of aging process, autophagy gradually loses its function and efficiency. Therefore, defects in autophagy prevent its normal function in removing damaged proteins and organelles that accumulate in senescent MSCs. However, various endogenous and exogenous stresses can induce autophagy of MSCs. For example, in senescent adipose-derives MSCs isolated from abdominal aortic aneurysm, treatment with an autophagy activator rapamycin efficiently decreased SASP levels, an indication of reduced senescence [35].

TREATMENT OF SENESCENT MSCS

In order to take full advantage of MSCs in therapy, stem cell exhaustion and cellular senescence must be overcome to restore their self-renew ability and differentiation properties. Various strategies have been proposed to remove, rejuvenate or replace (3Rs) the senescent MSCs. The treatment to intervene MSC senescence have been tested and described as follows.

Senolytics

Senolytics refer to the targeted elimination of the senescent cells to delay aging and age-related diseases. There are several pre-clinical studies in mice to show that senolytic drugs efficiently eliminated senescent cells and alleviated multiple age-related diseases, including age-related muscle loss, age-related osteoporosis, cardiac dysfunction, vascular dysfunction, pulmonary fibrosis, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and dementia [52]. The first generation of senolytics, dasatinib and quercetin, were tested by the Kirkland Group [53]. Dasatinib induced apotosis more effectively in senescent fat cell progenitors. Quercetin induced apoptosis more effectively in senescent endothelial cells. The combination of both alleviated senescence-associated phenotypes in damage-induced progeria and aged mice [53]. The same group reported another senolytic drug navitoclax, which is a BCL-2 family inhibitor. It worked effectively against human umbilical vein epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts [54]. Based on the first generation of senolytics, other drugs such as A1331852 and A1155463 have also worked on inhibiting BCL-2 family members [55]. The results of the first human clinical trial with dasatinib and quercetin were published last year. Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with senolytics showed significantly improved physical performance [56].

Although showing promises, the current senolytics have a few limitations. First, there might be undesirable side effects for long-term use. Navitoclax is known to cause severe thrombocytopenic and neutropenic effects [57] [58]. Second, removal of senescent cell by senolytic drugs can cause tissue atrophy. Since different tissues have various percentages of senescent cells, abrupt removal without specific targeting can result in the loss of normal roles of senescent cells, such as wound healing, cellular reprogramming, and tissue regeneration [59] [60] [61]. Therefore, careful consideration in treatment timing, dosage, tissue bio-availability, and administration route and duration must be given to improve senolytic drugs and their effects on eliminating senescent cells.

Rejuvenation: Antioxidant and other compounds

Many studies focused on rejuvenating senescent MSCs using genetic and cellular approaches. We summarized these studies in Table 1. One of the main causes for senescent MSCs is the accumulation of ROS. Several studies have shown that MSC senescence can be reversed by antioxidant through reduced ROS production. Ascorbic acid has been shown to inhibit ROS production through activation of AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in MSCs [62]. Lactoferrin inhibits ROS production induced by hydrogen peroxide through downregulating caspase-3. It reduces apoptosis by activating AKT [63]. N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) is a direct ROS scavenger and has been used to reduce the damaging effects of ROS [64]. MSCs pretreated with Cirsium setidens inhibit ROS production and decrease the expression of phosphorylated-p38 mitogen activated protein kinase and p53 [65].

Table 1.

Genetic/cellular intervention for MSC rejuvenation.

| Treatment | Mechanism | Target cell | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularized stem cell matrix (DSCM) | Promote antioxidation and chondrogenic potential | Human synovium-derived stem cell | 23092115, 22116651 |

| Lipocalin 2 (Lcn2) | Decrease senescence induced by H2O2 | Human bone marrow-derived MSCs | 24452457 |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) | Rescue from DOXO-induced senescence by inhibiting oxidative stress and activating the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | Rat bone marrow-derived MSCs | 29207187 |

| miR-195 inhibition | Induce telomere lengthening | Human bone marrow-derived MSCs | 26390028 |

| mmu-miR-291a-3p (Embryonic stem cell-derived) | Inhibit replicative, Adriamycininduced, and ionizing radiationinduced senescence through the TGF-β receptor 2 signaling pathway | Human dermal fibroblasts | 30239625 |

| Nampt overexpression | Rescue cell senescence through targeting Sirt1 | Rat bone marrow-derived MSCs | 28125705 |

| NANOG overexpression | Restore contractility of MSCs by increasing α-actin (ACTA2) expression | Human hair follicle MSCs | 28125933 |

| Neuron-derived neurotrophic factor (NDNF) overexpression | Rejuvenate aged stem cell, decrease cell senescence and apoptosis | Human bone marrow-derived MSCs | 30062183 |

| SIRT1 overexpression | Ameliorate senescent phenotype, increased stress response capabilities | Rat MSCs | 25034794 |

| SIRT3 overexpression | Reduce aging-related senescence, oxidative stress, and enhance ability to differentiate | Human bone marrow-derived MSCs | 28717408 |

| TERT overexpression | Increase telomere length and extend life-span | Human bone marrow-derived MSCs | 12042863 |

| Zebrafish embryo extract (ZF1) | Rescue telomerase activity and influence senescence related gene expression | Human adipose-derived stem cells | 30844738 |

Although not an antioxidant, melatonin also can reverse MSC senescence through increasing mitophagy and enhancing mitochondrial function. This effect occurs through upregulation of a heat shock protein HSPA1L, which will eventually lead to an increase in mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme activity [66]. It indirectly regulates downstream ROS production.

Because many stimuli can increase ROS production, the choice of antioxidant is important in each case. It is critical to identify the specific antioxidant that can achieve the most efficient ROS downregulation. Another potential problem of antioxidant treatment is its dosage. Study has found that high doses of antioxidant can cause DNA damage and induce premature senescence [67]. Therefore the use of antioxidant to rejuvenate MSCs needs to be carefully evaluated for their regulation of ROS production.

Rejuvenation: MicroRNA manipulation

It has been shown that many microRNAs can regulate MSC senescence through multiple targets. MiR-217 promotes cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived MSC by inhibiting DKK1 during steroid-associated osteonecrosis [68]. MiR-10b promotes osteogenic differentiation and bone formation of adipose-derived MSC through TGF-β signaling pathway, and plays a role in the regulation of balancing osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation [69]. MiR-1292 is positively correlated with senescence markers and negatively correlated with bone formation markers in adipose-derived MSCs. Pathway analysis shows that miR-1292 regulates senescence and osteogenesis through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [70]. Although a wide variety of miRNAs provides a possible solution to regulating MSC senescence, these studies were performed in vitro and correlative in nature. Future objectives will need to focus on targeted delivery of miRNA in vivo to determine its efficacy in regulating cell senescence process.

Reprogramming MSCs

MSC-based cell therapy is limited due to senescence-induced changes of functions in MSCs. To overcome the limitations of senescent MSCs, MSCs have been modified by cell reprogramming. There are two types of reprogramed MSCs. The first type is full reprogramming within iPSCs [71]. Functional MSCs have been successfully induced from iPSCs with improved cell vitality. These induced MSCs (iMSCs) exhibit typical features of MSCs with little epigenetic change [72]. In iMSCs derived from aged individuals, the cells show a rejuvenated profile and the age-related DNA methylation was completely erased [73]. However, this method has several disadvantages, such as low efficiency, limited available iMSCs, and high cost. A large gap still exists between the laboratory development and clinical application.

The second type is partial reprograming via epigenetic changes. This method is simpler than full reprogramming since the generation of rejuvenated MSCs does not require a dedifferentiation cycle. MSCs acquire senescence-associated modifications through time such as changes in DNA methylation [74]. The first epigenetic modulation on senescent MSCs is to regulate DNA methylation through silencing of the promoter regions. Inhibitors of DNA methyltransferase, such as 5-Azacytidine and RG108, can reverse the aged phenotype of MSCs or induce expression of key proteins in maintaining its normal phenotype [75] [76]. The second epigenetic modulation is histone modification. Through regulating a histone-lysine N-methyltransferase enzyme EZH2, tetramethypyrazine significantly inhibits the cell senescent phenotype [77, 78].

CONCLUSION

MSC senescence poses a significant challenge in the field of MSC-based therapy. The resulted restriction to the potential of therapeutic application highlights the importance of understanding the mechanisms of senescent MSCs in diseases. Two possibilities could explain the relation between senescent MSCs and associated disease. The first is a significant increase in the number of senescent MSCs due to stem cell exhaustion [43, 46]. This will hamper its normal stem cell function in tissue renewal, eventually resulting in organ degeneration and aging. Another is that the accumulated senescent MSCs secrete SASPs to the microenvironment and cause chronic inflammation. This process has the potential to affect normal cells around senescent MSCs to become inflammatory or degenerative, thereby accelerating the aging process. However, it remains to be proven whether SASP can directly cause normal cells to become senescent.

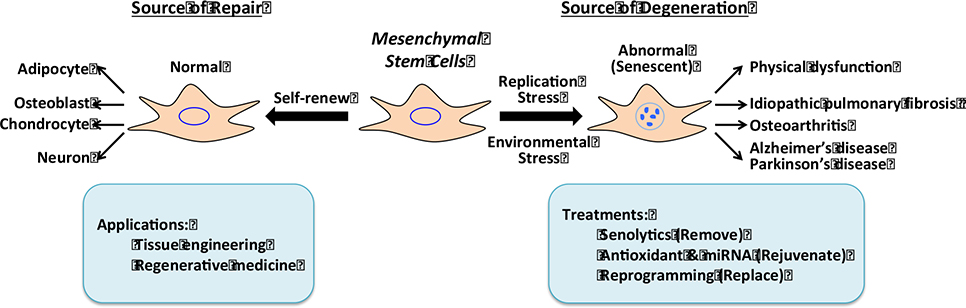

Evidence has emerged to show that senescent MSCs not only hamper tissue repair but also contribute to pathogenesis of various degenerative diseases. Therefore, it is critical to restore the normal function of MSCs to inhibit inflammation and facilitate tissue regeneration. The restoration of normal MSC functions may involve the “3Rs” strategy: Remove, Rejuvenate, and Replace (Figure 2). Senolytics are aimed at removing senescent MSCs by inducing their apoptosis, while antioxidants and miRNA treatments work by rejuvenating senescent MSCs. Epigenetic reprogramming can also rejuvenate senescent MSCs by resetting the epigenetic clock. Genetic reprogramming results in a fully reprogrammed iPSC, which can replace aged MSCs during tissue repair and engineering. As our current understanding in MSC senescence induced degenerative disease is not yet complete, future studies will shed light on new interventions of aging associated diseases by targeting senescent MSCs and developing more rational MSC-based cell therapy.

Figure 2.

Roles of normal and senescent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) during tissue repair. MSCs have the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into multiple cell lineages at a young age and/or in a normal tissue environment (self-renew). As a source of repair, MSCs can function in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (applications). However, MSCs can become senescent due to extensive replication and/or environmental stress at an old age or under chronical inflammatory conditions. The senescent MSCs may become a source of SASP and degeneration, and cause physical dysfunction and age-associated diseases. Development of efficient treatments will improve its use in MSC-based cell therapy.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by NIH R61 AR076807 and P30 GM122732 (to Q.C.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Yajun Liu declares no potential conflict of interest. Qian Chen holds patents relevant to human cartilage derived mesenchymal stem cells and is a co-founder of NanoDe Therapeutics Inc.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article contains no new studies with human and animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

Paper of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

*Of importance

**Of major importance

- 1.Pittenger MF, Discher DE, Péault BM, Phinney DG, Hare JM, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress. NPJ Regen Med. 2019;4:22. doi: 10.1038/s41536-019-0083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou X, Hong Y, Zhang H, Li X. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Senescence and Rejuvenation: Current Status and Challenges. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2020;8(364). doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Squillaro T, Peluso G, Galderisi U. Clinical Trials With Mesenchymal Stem Cells: An Update. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(5):829–48. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimmeler S, Leri A. Aging and disease as modifiers of efficacy of cell therapy. Circ Res. 2008;102(11):1319–30. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.108.175943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Wu Q, Wang Y, Li L, Bu H, Bao J. Senescence of mesenchymal stem cells (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2017;39(4):775–82. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neri S, Borzì RM. Molecular Mechanisms Contributing to Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Aging. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2). doi: 10.3390/biom10020340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou S, Greenberger JS, Epperly MW, Goff JP, Adler C, Leboff MS et al. Age-related intrinsic changes in human bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to osteoblasts. Aging Cell. 2008;7(3):335–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular Senescence in Aging Primates. Science. 2006;311(5765):1257-. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franzen J, Zirkel A, Blake J, Rath B, Benes V, Papantonis A et al. Senescence-associated DNA methylation is stochastically acquired in subpopulations of mesenchymal stem cells. Aging Cell. 2017;16(1):183–91. doi: 10.1111/acel.12544.* This work provides evidence of epigenetic modification of DNA associated with aging of MSCs.

- 11.Andrzejewska A, Lukomska B, Janowski M. Concise Review: Mesenchymal Stem Cells: From Roots to Boost. STEM CELLS. 2019;37(7):855–64. doi: 10.1002/stem.3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu N, Gao Y, Jayasuriya CT, Liu W, Du H, Ding J et al. Chondrogenic induction of human osteoarthritic cartilage-derived mesenchymal stem cells activates mineralization and hypertrophic and osteogenic gene expression through a mechanomiR. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1949-0.* This work demonstrates a microRNA dependent mechanism of alteration of differentiation potentials in senescent MSCs.

- 13.Rodier F, Campisi J. Four faces of cellular senescence. Journal of Cell Biology. 2011;192(4):547–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitinger S, Schimke M, Klepsch S, de Sneeuw S, Yani SL, Gaßner R et al. Systemic impact molds mesenchymal stromal/stem cell aging. Transfus Apher Sci. 2015;52(3):285–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akyurekli C, Le Y, Richardson RB, Fergusson D, Tay J, Allan DS. A systematic review of preclinical studies on the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived microvesicles. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2015;11(1):150–60. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie H, Wang Z, Zhang L, Lei Q, Zhao A, Wang H et al. Development of an angiogenesis-promoting microvesicle-alginate-polycaprolactone composite graft for bone tissue engineering applications. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2040. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan QL, Zhang YG, Chen Q. Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Potential Therapeutics as MSC Trophic Mediators in Regenerative Medicine. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2020;303(6):1735–42. doi: 10.1002/ar.24186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei Q, Liu T, Gao F, Xie H, Sun L, Zhao A et al. Microvesicles as Potential Biomarkers for the Identification of Senescence in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Theranostics. 2017;7(10):2673–89. doi: 10.7150/thno.18915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toussaint O, Medrano EE, von Zglinicki T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) of human diploid fibroblasts and melanocytes. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35(8):927–45. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stolzing A, Coleman N, Scutt A. Glucose-induced replicative senescence in mesenchymal stem cells. Rejuvenation Res. 2006;9(1):31–5. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severino V, Alessio N, Farina A, Sandomenico A, Cipollaro M, Peluso G et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 4 and 7 released by senescent cells promote premature senescence in mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(11):e911. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gharibi B, Farzadi S, Ghuman M, Hughes FJ. Inhibition of Akt/mTOR Attenuates Age-Related Changes in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. STEM CELLS. 2014;32(8):2256–66. doi: 10.1002/stem.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh J, Lee YD, Wagers AJ. Stem cell aging: mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):870–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hladik D, Höfig I, Oestreicher U, Beckers J, Matjanovski M, Bao X et al. Long-term culture of mesenchymal stem cells impairs ATM-dependent recognition of DNA breaks and increases genetic instability. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):218. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1334-6.* This work demonstrates molecular mechanisms of cell senescence in long term culture of MSCs.

- 25.Burhans WC, Weinberger M. DNA replication stress, genome instability and aging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(22):7545–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Wang L, Hou J, Li J, Chen L, Xia J et al. Study on the Dynamic Biological Characteristics of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Senescence. Stem Cells International. 2019;2019:9271595. doi: 10.1155/2019/9271595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong SG, Cho GW. Endogenous ROS levels are increased in replicative senescence in human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(4):971–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai TP, Wright WE, Shay JW. Comparison of telomere length measurement methods. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373(1741). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadeau S, Cheng A, Colmegna I, Rodier F. Quantifying Senescence-Associated Phenotypes in Primary Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Cultures. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;2045:93–105. doi: 10.1007/7651_2019_217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herranz N, Gil J. Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(4):1238–46. doi: 10.1172/jci95148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghanta S, Tsoyi K, Liu X, Nakahira K, Ith B, Coronata AA et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Deficient in Autophagy Proteins Are Susceptible to Oxidative Injury and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56(3):300–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0061OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Revuelta M, Matheu A. Autophagy in stem cell aging. Aging Cell. 2017;16(5):912–5. doi: 10.1111/acel.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckhart L, Tschachler E, Gruber F. Autophagic Control of Skin Aging. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:143. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortensen M, Watson AS, Simon AK. Lack of autophagy in the hematopoietic system leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell function and dysregulated myeloid proliferation. Autophagy. 2011;7(9):1069–70. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.15886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang X, Zhang H, Liang X, Hong Y, Mao M, Han Q et al. Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Isolated from Patients with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Exhibit Senescence Phenomena. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:1305049. doi: 10.1155/2019/1305049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldring MB. Articular cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis. Hss j. 2012;8(1):7–9. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(6):223. doi: 10.1186/ar4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alsalameh S, Amin R, Gemba T, Lotz M. Identification of mesenchymal progenitor cells in normal and osteoarthritic human articular cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1522–32. doi: 10.1002/art.20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hattori S, Oxford C, Reddi AH. Identification of superficial zone articular chondrocyte stem/progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358(1):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grogan SP, Miyaki S, Asahara H, D’Lima DD, Lotz MK. Mesenchymal progenitor cell markers in human articular cartilage: normal distribution and changes in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):R85. doi: 10.1186/ar2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fickert S, Fiedler J, Brenner RE. Identification of subpopulations with characteristics of mesenchymal progenitor cells from human osteoarthritic cartilage using triple staining for cell surface markers. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(5):R422–32. doi: 10.1186/ar1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su X, Zuo W, Wu Z, Chen J, Wu N, Ma P et al. CD146 as a new marker for an increased chondroprogenitor cell sub-population in the later stages of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(1):84–91. doi: 10.1002/jor.22731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayasuriya CT, Hu N, Li J, Lemme N, Terek R, Ehrlich MG et al. Molecular characterization of mesenchymal stem cells in human osteoarthritis cartilage reveals contribution to the OA phenotype. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7044. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25395-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malaise O, Tachikart Y, Constantinides M, Mumme M, Ferreira-Lopez R, Noack S et al. Mesenchymal stem cell senescence alleviates their intrinsic and seno-suppressive paracrine properties contributing to osteoarthritis development. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(20):9128–46. doi: 10.18632/aging.102379.* This study demonstrates a paracrine mechanism for the senescent MSCs in synovium and bone marrow to induce cartilage degeneration.

- 45.Martinez FJ, Collard HR, Pardo A, Raghu G, Richeldi L, Selman M et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17074. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cárdenes N, Álvarez D, Sellarés J, Peng Y, Corey C, Wecht S et al. Senescence of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0970-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, Weigand BM, Palmer AK, Weivoda MM et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1246–56. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9.** A groundbreaking study to demonstrate the anti-aging effects of senolytics in vivo.

- 48.Vicinanza C, Aquila I, Scalise M, Cristiano F, Marino F, Cianflone E et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and robustly myogenic: c-kit expression is necessary but not sufficient for their identification. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24(12):2101–16. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castaldi A, Dodia RM, Orogo AM, Zambrano CM, Najor RH, Gustafsson Å B et al. Decline in cellular function of aged mouse c-kit(+) cardiac progenitor cells. J Physiol. 2017;595(19):6249–62. doi: 10.1113/jp274775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis-McDougall FC, Ruchaya PJ, Domenjo-Vila E, Shin Teoh T, Prata L, Cottle BJ et al. Aged-senescent cells contribute to impaired heart regeneration. Aging Cell. 2019;18(3):e12931. doi: 10.1111/acel.12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicaise AM, Wagstaff LJ, Willis CM, Paisie C, Chandok H, Robson P et al. Cellular senescence in progenitor cells contributes to diminished remyelination potential in progressive multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(18):9030–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818348116.** A nice study to demonstrate the contribution of senescent neural stem cells to multiple sclerosis.

- 52.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. The Clinical Potential of Senolytic Drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(10):2297–301. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell. 2015;14(4):644–58. doi: 10.1111/acel.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Dai HM, Ling YY, Stout MB et al. Identification of a novel senolytic agent, navitoclax, targeting the Bcl-2 family of anti-apoptotic factors. Aging Cell. 2016;15(3):428–35. doi: 10.1111/acel.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Y, Doornebal EJ, Pirtskhalava T, Giorgadze N, Wentworth M, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H et al. New agents that target senescent cells: the flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-X(L) inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9(3):955–63. doi: 10.18632/aging.101202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Justice JN, Nambiar AM, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Pascual R, Hashmi SK et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:554–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.052.** One of the first clinical trials of senolytic treatment of a human aging disease.

- 57.McHugh D, Gil J. Senescence and aging: Causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(1):65–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201708092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson WH, O’Connor OA, Czuczman MS, LaCasce AS, Gerecitano JF, Leonard JP et al. Navitoclax, a targeted high-affinity inhibitor of BCL-2, in lymphoid malignancies: a phase 1 dose-escalation study of safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and antitumour activity. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(12):1149–59. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Demaria M, O’Leary MN, Chang J, Shao L, Liu S, Alimirah F et al. Cellular Senescence Promotes Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer Relapse. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(2):165–76. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-16-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Alcazar N, Marión RM, Chondronasiou D, Rovira M et al. Tissue damage and senescence provide critical signals for cellular reprogramming in vivo. Science. 2016;354(6315). doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ritschka B, Storer M, Mas A, Heinzmann F, Ortells MC, Morton JP et al. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype induces cellular plasticity and tissue regeneration. Genes Dev. 2017;31(2):172–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.290635.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang M, Teng S, Ma C, Yu Y, Wang P, Yi C. Ascorbic acid inhibits senescence in mesenchymal stem cells through ROS and AKT/mTOR signaling. Cytotechnology. 2018;70(5):1301–13. doi: 10.1007/s10616-018-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park SY, Jeong AJ, Kim GY, Jo A, Lee JE, Leem SH et al. Lactoferrin Protects Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Oxidative Stress-Induced Senescence and Apoptosis. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;27(10):1877–84. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1707.07040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin TM, Tsai JL, Lin SD, Lai CS, Chang CC. Accelerated growth and prolonged lifespan of adipose tissue-derived human mesenchymal stem cells in a medium using reduced calcium and antioxidants. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(1):92–102. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JH, Jung HK, Han YS, Yoon YM, Yun CW, Sun HY et al. Antioxidant effects of Cirsium setidens extract on oxidative stress in human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(4):3777–84. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee JH, Yoon YM, Song KH, Noh H, Lee SH. Melatonin suppresses senescence-derived mitochondrial dysfunction in mesenchymal stem cells via the HSPA1L-mitophagy pathway. Aging Cell. 2020;19(3):e13111. doi: 10.1111/acel.13111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kornienko JS, Smirnova IS, Pugovkina NA, Ivanova JS, Shilina MA, Grinchuk TM et al. High doses of synthetic antioxidants induce premature senescence in cultivated mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1296. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37972-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dai Z, Jin Y, Zheng J, Liu K, Zhao J, Zhang S et al. MiR-217 promotes cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by targeting DKK1 in steroid-associated osteonecrosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:1112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Fan J, Fan L, Li T, Yang Y, Xu H et al. MiRNA-10b Reciprocally Stimulates Osteogenesis and Inhibits Adipogenesis Partly through the TGF-β/SMAD2 Signaling Pathway. Aging Dis. 2018;9(6):1058–73. doi: 10.14336/ad.2018.0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fan J, An X, Yang Y, Xu H, Fan L, Deng L et al. MiR-1292 Targets FZD4 to Regulate Senescence and Osteogenic Differentiation of Stem Cells in TE/SJ/Mesenchymal Tissue System via the Wnt/β-catenin Pathway. Aging Dis. 2018;9(6):1103–21. doi: 10.14336/ad.2018.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galkin F, Zhang B, Dmitriev SE, Gladyshev VN. Reversibility of irreversible aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;49:104–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hynes K, Menicanin D, Han J, Marino V, Mrozik K, Gronthos S et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from iPS cells facilitate periodontal regeneration. J Dent Res. 2013;92(9):833–9. doi: 10.1177/0022034513498258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spitzhorn LS, Megges M, Wruck W, Rahman MS, Otte J, Degistirici Ö et al. Human iPSC-derived MSCs (iMSCs) from aged individuals acquire a rejuvenation signature. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fernandez-Rebollo E, Franzen J, Goetzke R, Hollmann J, Ostrowska A, Oliverio M et al. Senescence-Associated Metabolomic Phenotype in Primary and iPSC-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2020;14(2):201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kornicka K, Marycz K, Marędziak M, Tomaszewski KA, Nicpoń J. The effects of the DNA methyltranfserases inhibitor 5-Azacitidine on ageing, oxidative stress and DNA methylation of adipose derived stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(2):387–401. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Assis RIF, Wiench M, Silvério KG, da Silva RA, Feltran GDS, Sallum EA et al. RG108 increases NANOG and OCT4 in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells through global changes in DNA modifications and epigenetic activation. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao B, Lin X, Jing H, Fan J, Ji C, Jie Q et al. Local delivery of tetramethylpyrazine eliminates the senescent phenotype of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells and creates an anti-inflammatory and angiogenic environment in aging mice. Aging Cell. 2018;17(3):e12741. doi: 10.1111/acel.12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ito T, Teo YV, Evans SA, Neretti N, Sedivy JM. Regulation of Cellular Senescence by Polycomb Chromatin Modifiers through Distinct DNA Damage- and Histone Methylation-Dependent Pathways. Cell Rep. 2018;22(13):3480–92. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]