Abstract

Objective

To review and summarise the current evidence on the uptake of combustible cigarette smoking following e-cigarette use in non-smokers—including never-smokers, people not currently smoking and past smokers—through an umbrella review, systematic review and meta-analysis.

Design

Umbrella review, systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsychINFO (Ovid), Medline (Ovid) and Wiley Cochrane Library up to April 2020.

Results

Of 6225 results, 25 studies of non-smokers—never, not current and former smokers—with a baseline measure of e-cigarette use and an outcome measure of combustible smoking uptake were included. All 25 studies found increased risk of smoking uptake with e-cigarette exposure, although magnitude varied substantially. Using a random-effects model, comparing e-cigarette users versus non-e-cigarette users, among never-smokers at baseline the OR for smoking initiation was 3.19 (95% CI 2.44 to 4.16, I2 85.7%) and among non-smokers at baseline the OR for current smoking was 3.14 (95% CI 1.93 to 5.11, I2 91.0%). Among former smokers, smoking relapse was higher in e-cigarette users versus non-users (OR=2.40, 95% CI 1.50 to 3.83, I2 12.3%).

Conclusions

Across multiple settings, non-smokers who use e-cigarettes are consistently more likely than those avoiding e-cigarettes to initiate combustible cigarette smoking and become current smokers. The magnitude of this risk varied, with an average of around three times the odds. Former smokers using e-cigarettes have over twice the odds of relapse as non-e-cigarettes users. This study is the first to our knowledge to review and pool data on the latter topic.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020168596.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, respiratory medicine (see thoracic medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comprehensive and systematic literature search with pooled evidence from 25 published studies reviewed according to a prespecified protocol.

Inclusion of studies investigating all ages and types of non-smokers (never, not current and former).

Independent corroboration of results from previous studies, reviews and meta-analyses, while adding evidence on smoking uptake with e-cigarette exposure among former smokers.

The evidence is largely reliant on self-reported product use and the studies reviewed were observational in nature as it is not ethical or appropriate to randomise non-smokers to e-cigarette exposure.

While all studies reported significantly higher uptake of tobacco smoking among non-smokers exposed to e-cigarettes, compared with those not exposed, there was significant variation in the magnitude of the observed increase in risk; the results of the meta-analyses should therefore be considered to be an average of the published studies.

Introduction

Globally, combustible tobacco smoking results in over 8 million deaths each year.1 Due to vigorous public health interventions, smoking prevalence in Australia has declined substantially over the last 50 years.2 Nevertheless, 9.3% of the total disease burden (in disability-adjusted life years) was attributable to combustible tobacco use in 2015.3

E-cigarettes are a diverse group of battery-operated or rechargeable devices that heat a liquid (‘e-liquid’ or ‘e-juice’) to produce a vapour that users inhale. Although the composition of e-liquid varies, it typically contains a range of chemicals including propylene glycol and flavouring agents and are commonly used to deliver nicotine.4 The labelling of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS) is not always accurate, with reports of nicotine found in products labelled ENNDS.4 5

Studies indicate that in many countries, e-cigarette use among never-smoking youth is increasing.6–11 In Australia, the proportion of non-smokers aged 14 years or older who had ever used e-cigarettes increased from 4.9% in 2016 to 6.9% in 2019.12 The increase was particularly notable in young adults, with 20% of 18–24 years old non-smokers reporting e-cigarette use.12 E-cigarette use among youth is predominantly driven by curiosity and experimentation rather than smoking cessation.13–15 Evidence also suggests that most people who report ever e-cigarette do not graduate to regular e-cigarette use.15 16 Although the identification of risk factors for initiation of e-cigarette use is complex, it appears as though many are similar to those for smoking initiation.17 18

There are concerns that the use of e-cigarettes in never-smokers may increase the probability that they will try combustible tobacco cigarettes and go on to become regular smokers, particularly among youth and young adults.19 20 Furthermore, use of e-cigarettes could conceivably lead to combustible tobacco smoking relapse in former smokers. If e-cigarette use leads to more people smoking combustible cigarettes, compared with the number of people who have smoked in the absence of e-cigarettes, this would be a source of considerable public health harm.21 Thus, our primary research question is: among never smokers, current non-smokers and former smokers, how does e-cigarette use affect the subsequent risk of initiating use, current use and relapse to combustible tobacco cigarettes? This review aims to systematically update global contemporary population-level evidence on the relationship of e-cigarette use to smoking uptake.

Methods

This summary of the global evidence comprises an umbrella review of systematic reviews and a top-up systematic review of primary research not included in the systematic reviews of the umbrella review. The protocol was published online through PROSPERO.

Search strategy

The Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) format was used to structure the search (online supplemental table 1). Studies investigating the association between ENDS or ENNDS use among non-tobacco smokers and uptake of combustible cigarette smoking were included. E-cigarette use, cigarette smoking and uptake related search terms and keywords were used (online supplemental table 2). For both the umbrella review and the top-up systematic review, six databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO (Ovid), MEDLINE (Ovid) and Cochrane) were searched on 1 April 2020 (online supplemental table 3).

bmjopen-2020-045603supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies or randomised or non-randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining the exposure (e-cigarette use) and outcome (smoking uptake in current non-smokers) of interest were included in the umbrella review. For the top-up systematic review, individual prospective cohort studies or randomised or non-RCTs identified in the search and not included in the umbrella review studies, were included. Cross-sectional studies were excluded due to difficulties in establishing the temporal relationship between e-cigarette exposure and smoking uptake. Studies with a follow-up of less than 6 months or with abstracts not published in English were excluded. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in online supplemental table 1.

Data screening and extraction

EndNote and Covidence software were used for review management. Two authors of this review (ONB and LF) undertook initial screening, study selection, risk of bias assessment and data extraction. Titles and abstracts identified in the searches were screened using a checklist, followed by full-text screening. A forward and backward reference search using Scopus was performed from the final included articles. After removing duplicates, titles, abstracts and then full texts were screened for any studies fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were independently extracted from the included systematic reviews and cohort studies using a prespecified data extraction template. As it is important to consider whether authors of the studies under review hold any conflicts of interest that could potentially bias their findings, or whether the research was funded by an organisation with a financial interest in the outcomes, information on the source of research sponsorship or external involvement was also extracted. Studies were considered separately if they received funding from the tobacco or nicotine industry.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias for each study included was independently assessed using the AMSTAR 222 for the systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the umbrella reviews, and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)23 for the studies in the top-up systematic review. For meta-analyses with at least 10 studies, risk of bias across studies was assessed and interpreted using the symmetry of funnel plots and superimposed 95% confidence limits.24

Summary measures and synthesis of results

Findings from the umbrella review and the top-up systematic review were synthesised separately in narrative summaries. Individual prospective primary research studies identified from both the umbrella review and top-up systematic review were then considered in an integrated systematic review. Where appropriate, ORs from the studies in the integrated systematic review were combined using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity of study effect estimates were assessed by an I2 statistic. All analyses were conducted using Stata V.16.1.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Study selection

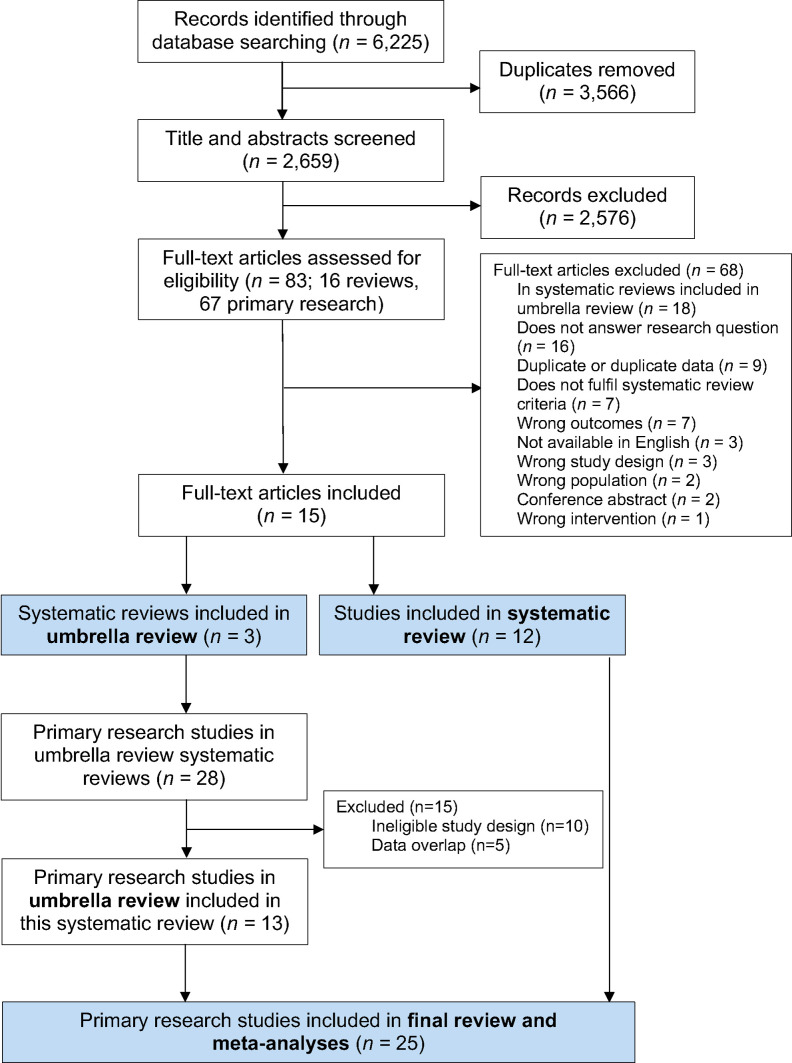

Study selection for this umbrella review and top-up systematic review are shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart in figure 1. A total of 6225 studies were identified for title and abstract screening; 2659 remained after exclusion of duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 83 articles were identified for full-text screening. Fifteen papers were identified for inclusion; three were systematic reviews that were included in the umbrella review and 12 were primary research studies included in the top-up systematic review. Ten of the latter studies were prospective observational studies and two were secondary analyses of RCTs.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selection of studies for inclusion in umbrella review and top-up systematic review.

From the three systematic review papers included in the umbrella review, 28 primary research studies were identified after removing duplicates. For our meta-analyses, we excluded 15 studies due to ineligible study design (n=10) or data overlap (n=5). No studies were excluded based on their quality assessment scores. The meta-analyses were thus based on 13 primary research studies identified from the prior systematic reviews, and 12 studies from our top-up systematic review, that is, a total of 25 primary research studies on e-cigarette use and smoking uptake (figure 1).

No potential competing interests were identified in the included studies themselves, or by the authors, based on the disclosure statements from the publications. Although one25 primary research study identified during screening in the top-up systematic review was found to have potential competing interests, as it was funded by the tobacco industry, it was previously excluded due to a large overlap with data presented in a more recent paper by Berry et al.26

There is considerable uncertainty regarding the chemical constituents of the e-liquids delivered by the e-cigarettes in the studies included in the review. Where evidence on nicotine content was available, it indicated that a substantial majority of e-cigarettes in those studies delivered nicotine.27–30 Many publications noted considerable uncertainty regarding nicotine content, including apparent mislabelling, and the need for greater clarity and reliability on this point.

Umbrella review: quality assessment

All three systematic reviews from the selected articles rated moderate in the AMSTAR 222 assessment. Information was lacking regarding study exclusion criteria, stated sources of funding and detail on data extraction (online supplemental table 4).

Umbrella review

Table 1 summarises the results of the three systematic reviews included in the umbrella review. All three systematic reviews excluded studies with participants over 30 years of age. Sample sizes for the individual studies varied considerably, ranging from 298 to 17 318. Of the 13 included longitudinal primary research studies (detailed in online supplemental table 5), 920 31–38 were based in the USA, 239 40 in the UK and 1 each in Mexico,41 and the Netherlands.42 Each of the three systematic reviews conducted meta-analyses and found the odds of smoking initiation were increased for youth and young adult e-cigarette users compared with non-e-cigarette users; these results are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

ORs and adjusted ORs of the association between e-cigarette use and combustible cigarette smoking from systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the umbrella review

| Authors/year | Studies included (n=total population) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) and heterogeneity (I2) |

| Khouja et al43 | 17 (n=105 448) | 4.59 (3.60 to 5.85) | 2.92 (2.30 to 3.71) I2: 84.5% |

| Aladeokin and Haighton44 | 8 (n=73 076) | 5.55 (3.94 to 1.82) | 3.86 (2.18 to 6.82) I2: 74% |

| Soneji et al21 | 9 (n=17 389) | Initiation: 3.83 (3.74 to 3.91) | Initiation: 3.50 (2.38 to 5.16) I2: 56% |

| Past 30-day: 5.68 (3.49 to 9.24) | Past 30-day: 4.28 (2.52 to 7.27) I2: 0% |

The Khouja et al systematic review and meta-analysis included 17 studies published up to November 2018.43 The study found that the risk of later smoking in people aged <30 years who had ever used or currently use e-cigarettes was strong; an almost threefold the odds compared with never users after adjustment for covariates (see table 1). However, there were high levels of heterogeneity in the summary estimates (adjusted OR I2=84.5%), which remained high in adjusted analysis subgrouping by age, ever smoking, risk of bias and location of study. Heterogeneity was reduced when the adjusted ORs were grouped into those examining the relationship between ever e-cigarette use and current smoking (adjusted OR 2.21; 95% CI 1.72 to 2.84, I2=5%) and those assessing the relationship of current e-cigarette use to ever smoking (adjusted OR 2.33; 95% CI 1.84 to 2.96, I2=5%).

Aladeokin and Haighton aimed to systematically review the evidence on e-cigarette use and initiation of cigarette smoking in adolescents (aged 10–19 years old) in the UK and included eight studies.44 Their meta-analysis showed e-cigarette users were much more likely than non-users to go on to smoke combustible cigarettes, even after adjusting for covariates (see table 1); the substantial heterogeneity in the summary estimate should be noted.

The Soneji et al systematic review and meta-analysis included nine longitudinal studies of US participants ≤30 years of age.21 Seven of the included studies assessed the association of baseline ever e-cigarette use with subsequent ever combustible cigarette use at follow-up among baseline never smokers. Soneji et al also identified two studies that assessed baseline past 30-day e-cigarette use with subsequent past 30-day combustible cigarette use among those reporting no past 30-day use of cigarettes at baseline. The meta-analysis showed a markedly higher odds of combustible cigarette use in those who had used e-cigarettes (table 1).

Top-up systematic review: quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the NOS.23 Of the 12 studies, the NOS totals (out of 10 stars) ranged from 5 to 8 (online supplemental table 6). Only one45 study rated 5, five28–30 46 47 rated 6, two9 48 rated 7 and four26 49–51 rated 8. No studies received a star for assessment of outcome. The main areas impacting the NOS scores were ascertainment of exposure and adequacy of follow-up of cohorts (studies with less than 30% loss to follow-up were considered adequate).

Top-up systematic review and integration with primary research studies from the umbrella review

A total of 12 studies published in 2018, 2019 and 2020 were newly identified for the top-up systematic review (table 2; online supplemental table 7). Among the 12 included, 6 were from the USA, 2 from the UK and 1 each from Romania, Finland, Taiwan and Canada. Study sample sizes varied considerably, ranging from 374 to 14 623.

Table 2.

ORs and adjusted ORs of the association between e-cigarette use and subsequent combustible cigarette use for: (1) never-smokers at baseline, (2) non-smokers* (never or no current use) at baseline and (3) former smokers at baseline

| Authors/year | Country | Baseline cigarette use | E-cigarette use | Follow-up cigarette use | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Initiation in never smokers at baseline | ||||||

| Berry et al26 | USA | Never | Ever | Ever | 4.09 (2.97 to 5.63) | |

| Chien et al27 | Taiwan | Never | Ever | Ever | 2.44 (1.94 to 3.09) | 2.14 (1.66 to 2.75) |

| Conner et al47 | UK (England) | Never | Ever | Ever | 4.03 (3.33 to 4.88) | 2.78 (2.20 to 3.51) |

| McMillen et al50 | USA | Never | Current† | Ever | 16.4 (9.8 to 27.5) | 6.6 (3.7 to 11.8) |

| Pénzes et al46 | Romania | Never | Ever | Ever | 2.75 (1.52 to 4.96) | 3.57 (1.96 to 6.49) |

| Current use in non-smokers at baseline | ||||||

| Aleyan et al28 | Canada | Non-smokers* | Current† | Current† | Wave 1–2: 1.54 (1.37 to 1.74) | |

| Wave 2–3: 1.18 (1.08 to 1.29) | ||||||

| Barrington-Trimis et al48 | USA | Never | Current† | Current† | NHW to dual use: 7.44 (3.63 to 15.3) | |

| HW to dual use: 3.64 (1.62 to 8.18) | ||||||

| Bold et al45 | USA | No current* | Current† | Current† | Wave 1–2: 7.08 (2.34 to 21.42) | |

| Wave 2–3: 3.87 (1.86 to 8.06) | ||||||

| Conner et al47 | UK (England) | Never | Ever | Current† | 3.38 (2.72 to 4.21) | 2.17 (1.76 to 2.69) |

| Regular‡ | 3.60 (2.35 to 5.51) | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.39) | ||||

| Kinnunen et al29 | Finland | Never | Ever nicotine-containing | Daily | 11.52 (4.91 to 27.01) | 8.50 (2.14 to 29.19) With school clustering: 2.92 (1.09 to 7.85) |

| Ever non-nicotine containing | 1.88 (0.25 to 14.45) | 2.50 (0.25 to 12.05) With school clustering: 0.94 (0.22 to 4.08) | ||||

| McMillen et al50 | USA | Never | Ever (not current) | Established§ | 5.9 (1.7 to 20.7) | 2.5 (0.6 to 10.9) |

| Current† | 25.5 (10.6 to 61.4) | 8.0 (2.8 to 22.7) | ||||

| Osibogun et al49 | USA | Non-smokers* | Current† | Regular‡ | Year 1: 16.4 (7.8 to 34.5) | Year 1: 5.0 (1.9 to 12.8) |

| Year 2: 11.1 (3.5 to 35.2) | Year 2: 3.4 (1.0 to 11.5) | |||||

| Relapse in former smokers at baseline | ||||||

| Brose et al30 | UK | ≥2-month ex-smokers | Ever | Ever | 1.52 (0.88 to 2.62) | 1.13 (0.61 to 2.07) |

| Non-daily | 3.32 (1.23 to 8.96) | 2.45 (0.85 to 7.08) | ||||

| Dai and Leventhal51 | USA | >12-month ex-smokers | Current† | Ever | 6.36 (4.49 to 9.00) | 2.00 (1.25 to 3.20) |

| Occasional | 5.79 (1.50 to 22.33) | 1.56 (0.34 to 7.14) | ||||

| Prior | 9.68 (4.74 to 19.75) | 3.77 (1.48 to 9.65) | ||||

| McMillen et al50 | USA | ≥5 years ex-smokers | Ever (not current†) | Ever | 5.4 (2.9 to 10.2) | 3.3 (1.6 to 6.7) |

| Current† | 7.6 (3.0 to 19.4) | 5.2 (1.6 to 16.3) | ||||

*Non-smokers defined as never or no current (past 30-day) use.

†Current defined as past 30-day use.

‡Regular defined as ≥20 days/30 days.

§Established defined as ≥100 combustible cigarettes and currently smokes every day or some.

HW, Hispanic white; NHW, non-Hispanic white.

Of the six newly identified studies based on US participants, four26 49–51 used Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) data from a US nationally representative longitudinal study. Of these, two50 51 looked at adult (≥18 years old) former smokers, one49 looked at youth (12–17 years old) and one26 at a more restricted youth group (12–15 years old). Even though these four studies have the same data source, they were all included in this review as they had different outcome or exposure variables, different populations and included the most recent data.

Of the 12 newly identified studies, five26 27 46 47 50 had outcomes assessing ever smoking among never smokers at baseline, seven28 29 45 47–50 had outcomes assessing current smoking among non-smokers (never or not current smoking) at baseline and three30 50 51 assessed the odds of relapse in former smokers. Results were separated based on these three categories and combined with the 13 primary research studies identified in the umbrella review. Twelve of the seventeen studies in Khouja et al were included,20 31 33–42 three were excluded due to data overlap,52–54 one was excluded as it used retrospective data55 and one was excluded as it was cross-sectional.56 Of the eight studies in Aladeokin and Haighton, two were included39 40; five were excluded for cross-sectional design57–61 and one for data overlap.54 From the nine studies identified in Soneji et al six were included31–34 36 37 after two were excluded as they were abstracts and one excluded for data overlap.62

Cigarette smoking initiation among never smokers at baseline

Five26 27 46 47 50 of the newly identified studies investigated smoking initiation among never smokers, of which Berry et al26 and McMillen et al50 used PATH data, focusing on youth (12–15 years old) and adults (≥18 years old), respectively (table 2). Chien et al examined the association between ever e-cigarette and subsequent combustible smoking initiation in 12 954 youth enrolled in schools in Taiwan between 2014 and 2016.27 Conner et al investigated the association of e-cigarette use at baseline and smoking in adolescents (13–14 years old) between waves 3 and 5 (2014–2016) of a cluster RCT in 20 schools in England.47 Pénzes et al conducted secondary data analysis from 1369 ninth grade students in the Romanian ASPIRA RCT. Details of the studies are given in online supplemental table 7.46.

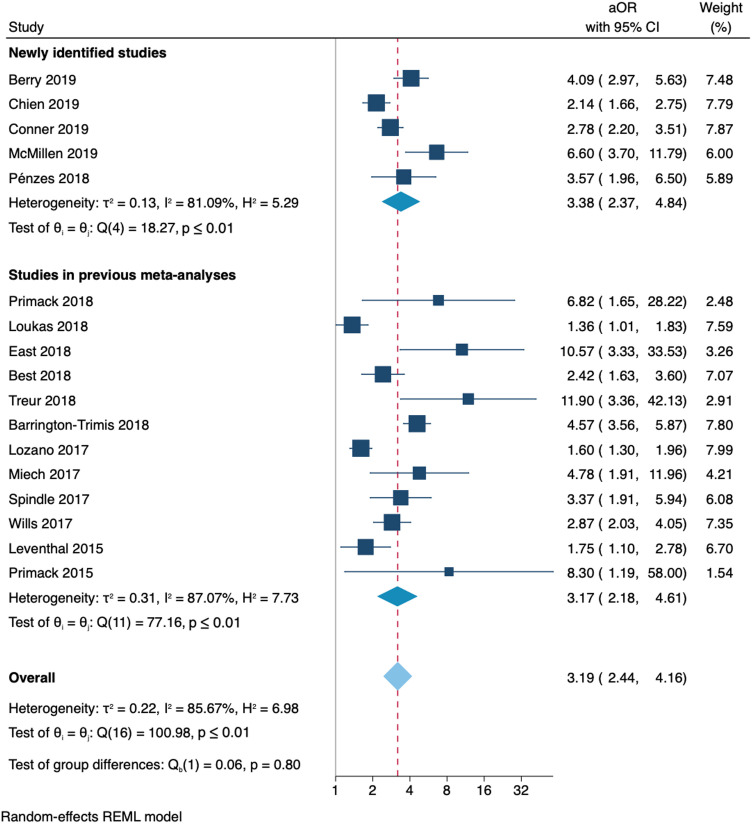

All newly identified studies found that people who used e-cigarettes were significantly more likely than non-users to initiate smoking of combustible cigarettes, with ORs varying substantially from 2.1 to 6.6 (I2=81%; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot and random-effects meta-analysis for the adjusted odds of smoking initiation at follow-up among never smokers and current e-cigarette users at baseline compared with never e-cigarette users at baseline. aOR, adjusted OR; REML, Restricted Maximum Likelihood

Considering these newly identified studies along with 12 studies from the umbrella review, all found significantly increased risk of initiating smoking of combustible cigarettes in people who had used e-cigarettes, compared with those who had not (figure 2). Combining the studies from the umbrella review with the newly identified studies, people exposed to e-cigarettes more likely to take up smoking of combustible cigarettes than people who were not exposed to e-cigarettes (pooled adjusted OR 3.19 (95% CI 2.44 to 4.16)).

Current (past 30-day) cigarette smoking among non-smokers (never smokers or no current use at baseline)

Seven28 29 45 47–50 of the newly identified primary research studies investigated current (past 30-day) use of combustible cigarettes following the use of e-cigarettes (table 2). Four29 47 48 50 of these studies looked at never smokers at baseline, while three28 45 49 looked at non-smokers (either never or no current use).

Two49 50 of the included studies were based on PATH data. McMillen et al50 used data on adult (≥18 years old) never smokers from waves 1 to 2 of the PATH study and Osibogun et al49 used data on youth (12–17 years old) non-smokers from waves 1 to 3. A further two45 48 of the newly identified studies used data from the USA. Bold et al surveyed 808 high school students across three waves (2013–2015) in Connecticut.45 Barrington-Trimis et al collated data on 6258 youth from three US school-based studies between 2013 and 2015: the Children’s Health Study; the Happiness and Health Study and the Yale Adolescent Survey Study.48 This study separated results based on ethnicity and found the adjusted odds of dual use at follow-up was considerably higher in non-Hispanic whites compared with Hispanic whites (see table 2), although with considerable overlap in the CIs.

The remaining three28 29 47 newly identified studies used data from Canada, the UK and Finland. Aleyan et al examined the association between current e-cigarette use and subsequent current smoking among 6729 Canadian school students using data from a school-based longitudinal cohort study, COMPASS.28 Conner et al investigated the association of e-cigarette use at baseline and smoking between waves 3 and 5 (2014–2016) of a cluster RCT assessing a self-regulation anti-smoking intervention from 20 schools in England.47 Kinnunen et al used MEtLoFIN a school-based longitudinal cohort dataset in 3474 Finnish adolescents between 2014 and 2016.29 Kinnunen et al separated the use of e-cigarettes based on their nicotine delivery and found among baseline never-smokers, ever use of nicotine-delivering e-cigarettes was associated with a nearly threefold increase in the odds of uptake of daily smoking (see table 2) and found no increase in risk associated with use of non-nicotine delivering e-cigarettes.

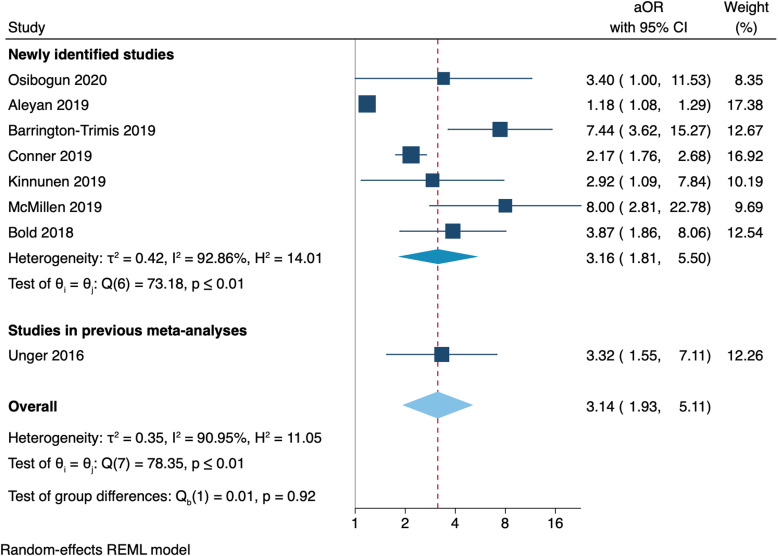

All of the newly identified studies, and the one relevant study from the umbrella review,32 found a significant increase in the risk of transitioning from being a non-smoker to a current smoker in people who had used e-cigarettes compared with not using e-cigarettes, but with considerable heterogeneity in the estimates (I2=91%; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot and random-effects meta-analysis for the adjusted odds of current (past 30-day) smoking at follow-up among non-current smokers and current e-cigarette users at baseline compared with non-current e-cigarette users at baseline.aOR, adjusted OR; REML, Restricted Maximum Likelihood

Cigarette smoking relapse among former smokers (at least 2 months since quit date)

Three30 50 51 newly identified studies in this review investigated the odds of relapse to combustible cigarette smoking following the use of e-cigarettes in adults aged ≥18 years (table 2). None of the three previously conducted systematic reviews investigated this relationship, so no additional studies from the umbrella review were included. Brose et al used data from 371 adults who quit ≥2 months prior to baseline in 2016 from a national web-based survey in the UK.30 The other two studies used PATH data. Dai and Leventhal looked at 3210 ex-smokers, who had not smoked for >12 months.51 McMillen et al looked at data relating to 8108 adults who had quit ≥5 years prior to baseline; subanalyses from this study were included in the previous two sections, as the study also provided data on never smokers.50

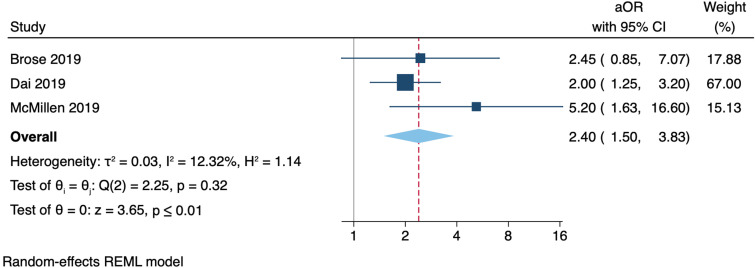

All three included studies found the odds of ever relapse was higher among ever e-cigarette users, compared with never e-cigarette users (figure 4). With respect to more detailed findings, in addition to the prespecified meta-analyes, Brose et al reported lower odds of relapse among recent ex-smokers who vaped daily versus those who vaped non-daily, while Dai and Leventhal and McMillen et al showed past 30-day regular e-cigarette use had greater odds of relapse than non-current use.30 50 51 Within the Dai and Leventhal study, regular e-cigarette use in recent smokers (quit ≤12 months) was not associated with smoking relapse.51 However, regular e-cigarette use in those who had ceased smoking for more than 12 months was associated with a significant increase in the odds of relapse. A meta-analysis of the three newly identified studies found former smokers who used e-cigarettes had 2.4 times greater odds of relapse when compared with those who did not use e-cigarettes, with similar magnitudes of this relationship between studies (I2=12%) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot and random-effects meta-analysis for the adjusted odds of smoking relapse at follow-up among former smokers and current e-cigarette users at baseline compared with never e-cigarette users at baseline. aOR, adjusted OR; REML, Restricted Maximum Likelihood

Risk of bias across studies

Funnel plots corresponding to the studies included in the meta-analyses are presented in online supplemental figure 1. The plot for the 17 smoking initiation studies of never-smokers is somewhat asymmetrical and seven points lie outside the 95% confidence region, suggesting there may be some selection bias across included studies, publication bias or possible heterogeneity (as supported by the I2 statistic; 86%). With less than ten studies investigating current smoking in non-smokers28 29 32 45 47–49 and relapse in former smokers,30 50 51 test for funnel plot asymmetry was not used as the power of the test would be too low for it to be a reliable indicator of publication bias.24

Discussion

Our umbrella and systematic review, along with an updated meta-analysis using data from primary studies, shows strong and consistent evidence that never smokers who have used e-cigarettes are more likely than those who have not used e-cigarettes to try smoking conventional cigarettes and to transition to become regular tobacco smokers. We found that, on average, non-smokers who used e-cigarettes have around threefold the odds of either initiating smoking or currently smoking combustible cigarettes compared with non-smokers who have not used e-cigarettes. The limited available evidence indicates that former smokers who report current e-cigarette use within the previous 30-days have more than twice the odds of relapse and resumption of current smoking compared with former smokers who have not used e-cigarettes.

This review builds on and has findings consistent with earlier systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the peer-reviewed and grey literature.11 21 43 44 63 64 A 2018 review by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on the public health consequences of e-cigarettes concludes that there is substantial evidence that e-cigarette use increases risk of ever using combustible tobacco cigarettes, and moderate evidence that e-cigarette use increases the frequency and intensity of subsequent combustible tobacco smoking, among youth and young adults.64 Previous systematic reviews have focused on evidence in those 30 years of age or less, whereas our review included data on adults and former smokers. This is the first systematic review to examine whether e-cigarette use is associated with smoking relapse.

The use of e-cigarettes may represent a risk factor for cigarette smoking initiation, current smoking and relapse to cigarette smoking for several behavioural and physiological reasons. For those who use nicotine-delivering e-cigarettes, a resulting addiction to nicotine may leave users at risk of seeking other forms of inhalable nicotine, such as combustible cigarettes.65 66 Additionally, as e-cigarettes can mimic behavioural (eg, hand-mouth) and sensory (eg, taste) aspects of smoking, associated e-cigarette habits and movements may make the transition to combustible smoking more natural.67 68 Further studies should examine potential mediators to better understand possible mechanisms for the association between e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette use. Although one study showed that an intervention designed to reduce smoking initiation in adolescents through self-regulatory implementation intentions attenuated the odds of smoking uptake in never smokers who used e-cigarettes, a statistically significant increased odds remained.47

Although studies in this review were consistent in finding increased risks of smoking uptake in non-smokers exposed to e-cigarettes, the magnitude of this increased risk varied substantially between studies. The reason for this variation is unclear, but may relate to the different products, populations and policy environments. In addition, it is challenging to estimate the overall effect of e-cigarettes on smoking initiation due to the variety of ways in which devices (eg, e-cigarettes, JUULs, pods, vape pens) and users (eg, never-users, ever-users, current-users, former users) are classified. The high heterogeneity in most of the results from the meta-analyses suggests that pooled ORs should be interpreted as an average of disparate results, rather than a reflection of the true underlying effect.

A limitation in this review is that included studies were limited to those written in English. While emerging results from this review and similar studies provide evidence regarding the association between e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use, the evidence is heavily weighted towards US and UK data. Only nine countries were included in this analysis, with a notable lack of data from the Asia-Pacific, Africa and the Middle East. Furthermore, the studies were reliant on self-reported product use, which is likely to be subject to self-reporting bias. All three systematic reviews rated moderate in the AMSTAR 2 risk of bias assessment and the 12 newly identified studies rated between 5 and 8 on the NOS. Although the consistency of findings across multiple studies and settings supports the likelihood of a causal relationship, given the observational nature of many of the included studies, the findings may be potentially influenced by confounding factors, including socioeconomic status and the tendency for risk behaviours to occur together. As the ability to adjust for such confounding factors varied according to study, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded.

Conclusion

This review found consistent evidence that use of e-cigarettes, largely nicotine-delivering, is associated with increased risk of subsequent combustible smoking initiation, current combustible smoking and smoking relapse after accounting for known demographic, psychosocial and behavioural risk factors. This is the first review to examine associations between e-cigarette use and cigarette use across the whole population, including youth, adults and former smokers. Intervention efforts and policies surrounding e-cigarettes are needed to reduce the potential of furthering combustible tobacco use in Australia and beyond.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

EB is supported by a Principal Research Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (reference: 1136128).

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published. The data in the abstract section has been modified.

Contributors: ONB, LF and EB all contributed to the study conception and design and interpretation of data. GJ and AY assisted with statistical analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript.

Funding: This review was developed as part of an independent programme of work examining the health impacts of e-cigarettes, funded by the Australian Government Department of Health. EB is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Principal Research Fellowship: 1136128).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data used in the manuscript are from published research.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Tobacco, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/tobacco [Accessed 31 Oct 2019].

- 2.Guerin NW, ASSAD V. Statistics & trends: australian secondary students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, over-the-counter drugs, and illicit substances. 2018. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australian burden of disease study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Canberra: AIHW, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farsalinos K. Electronic cigarettes: an aid in smoking cessation, or a new health hazard? Ther Adv Respir Dis 2018;12:1753465817744960. 10.1177/1753465817744960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chivers E, Janka M, Franklin P, et al. Nicotine and other potentially harmful compounds in “nicotine-free” e-cigarette liquids in Australia. Med J Aust 2019;210:127–8. 10.5694/mja2.12059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services . E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorini G, Gallus S, Carreras G, et al. Prevalence of tobacco smoking and electronic cigarette use among adolescents in Italy: global youth tobacco surveys (GYTS), 2010, 2014, 2018. Prev Med 2020;131:105903. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DM, Gawron M, Balwicki L, et al. Exclusive versus dual use of tobacco and electronic cigarettes among adolescents in Poland, 2010-2016. Addict Behav 2019;90:341–8. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen P-C, Chang L-C, Hsu C, et al. Dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes among adolescents in Taiwan, 2014-2016. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:48–54. 10.1093/ntr/nty003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho H-J, Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Differences in adolescent e-cigarette and cigarette prevalence in two policy environments: South Korea and the United States. Nicotine Tobacco Research 2018;20:949–53. 10.1093/ntr/ntx198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, et al. Vaping in England: an evidence update including mental health and pregnancy, March 2020: a report commissioned by public health England. London: Public Health England, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.AIHW . Australian Institute of health and welfare 2020. National drug strategy household survey 2019. Drug Statistics 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wamamili B, Wallace-Bell M, Richardson A, et al. Electronic cigarette use among university students aged 18-24 years in New Zealand: results of a 2018 national cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2020;10:e035093. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick ME, Miech RA, Carlier C, et al. Self-reported reasons for vaping among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the US: Nationally-representative results. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;165:275–8. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leavens ELS, Stevens EM, Brett EI, et al. JUUL electronic cigarette use patterns, other tobacco product use, and reasons for use among ever users: results from a convenience sample. Addict Behav 2019;95:178–83. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker MA, Villanti AC. Patterns and frequency of current e-cigarette use in United States adults. Subst Use Misuse 2019;54:2075–81. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1626433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunbar MS, Davis JP, Rodriguez A, et al. Disentangling within- and between-person effects of shared risk factors on e-cigarette and cigarette use trajectories from late adolescence to young adulthood. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:1414–22. 10.1093/ntr/nty179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Selya AS. The relationship between electronic cigarette use and conventional cigarette smoking is largely attributable to shared risk factors. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:1123–30. 10.1093/ntr/ntz157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasser AM, Johnson AL, Niaura RS, et al. Youth vaping and tobacco use in context in the United States: results from the 2018 national youth tobacco survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loukas A, Marti CN, Cooper M, et al. Exclusive e-cigarette use predicts cigarette initiation among college students. Addict Behav 2018;76:343–7. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:788–97. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002. 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee P, Fry J. Investigating gateway effects using the path study. F1000Res 2019;8:264. 10.12688/f1000research.18354.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry KM, Fetterman JL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with subsequent initiation of tobacco cigarettes in US youths. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e187794. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chien Y-N, Gao W, Sanna M, et al. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation in Taiwan: evidence from the first prospective study in Asia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16 10.3390/ijerph16071145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aleyan S, Gohari MR, Cole AG, et al. Exploring the bi-directional association between tobacco and e-cigarette use among youth in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16 10.3390/ijerph16214256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinnunen JM, Ollila H, Minkkinen J, et al. Nicotine matters in predicting subsequent smoking after e-cigarette experimentation: a longitudinal study among Finnish adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;201:182–7. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brose LS, Bowen J, McNeill A, et al. Associations between vaping and relapse to smoking: preliminary findings from a longitudinal survey in the UK. Harm Reduct J 2019;16:76. 10.1186/s12954-019-0344-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, et al. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tob Control 2017;26:34–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unger JB, Soto DW, Leventhal A. E-Cigarette use and subsequent cigarette and marijuana use among Hispanic young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;163:261–4. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spindle TR, Hiler MM, Cooke ME, et al. Electronic cigarette use and uptake of cigarette smoking: a longitudinal examination of U.S. college students. Addict Behav 2017;67:66–72. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, et al. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:1018–23. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Primack BA, Shensa A, Sidani JE, et al. Initiation of traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among Tobacco-Naïve US young adults. Am J Med 2018;131:443.e1–9. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miech R, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, et al. E-cigarette use as a predictor of cigarette smoking: results from a 1-year follow-up of a national sample of 12th grade students. Tob Control 2017;26:e106–11. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of Combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA 2015;314:700–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrington-Trimis JL, Kong G, Leventhal AM, et al. E-cigarette use and subsequent smoking frequency among adolescents. Pediatrics 2018;142 10.1542/peds.2018-0486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.East K, Hitchman SC, Bakolis I, et al. The association between smoking and electronic cigarette use in a cohort of young people. J Adolescent Health 2018;62:539–47. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Best C, Haseen F, Currie D, et al. Relationship between trying an electronic cigarette and subsequent cigarette experimentation in Scottish adolescents: a cohort study. Tobacco Control 2018;27:373–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;180:427–30. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Treur JL, Rozema AD, Mathijssen JJP, et al. E-cigarette and waterpipe use in two adolescent cohorts: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with conventional cigarette smoking. Eur J Epidemiol 2018;33:323–34. 10.1007/s10654-017-0345-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khouja JN, Suddell SF, Peters SE. Is e-cigarette use in non-smoking young adults associated with later smoking? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control 2020:15. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aladeokin A, Haighton C. Is adolescent e-cigarette use associated with smoking in the United Kingdom?: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Tobacco Prevent Cessat 2019;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bold KW, Kong G, Camenga DR, et al. Trajectories of e-cigarette and conventional cigarette use among youth. Pediatrics 2018;141 10.1542/peds.2017-1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pénzes M, Foley KL, Nădășan V, et al. Bidirectional associations of e-cigarette, conventional cigarette and waterpipe experimentation among adolescents: a cross-lagged model. Addict Behav 2018;80:59–64. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conner M, Grogan S, Simms-Ellis R, et al. Evidence that an intervention weakens the relationship between adolescent electronic cigarette use and tobacco smoking: a 24-month prospective study. Tob Control 2020;29:425–31. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrington-Trimis JL, Bello MS, Liu F, et al. Ethnic differences in patterns of cigarette and e-cigarette use over time among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2019;65:359–65. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osibogun O, Bursac Z, Maziak W. E-Cigarette use and regular cigarette smoking among youth: population assessment of tobacco and health study (2013-2016). Am J Prev Med 2020;58:657–65. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMillen R, Klein JD, Wilson K, et al. E-Cigarette use and future cigarette initiation among never smokers and relapse among former smokers in the path study. Public Health Rep 2019;134:528–36. 10.1177/0033354919864369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dai H, Leventhal AM. Association of electronic cigarette vaping and subsequent smoking relapse among former smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;199:10–17. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watkins SL, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW. Association of Noncigarette tobacco product use with future cigarette smoking among youth in the population assessment of tobacco and health (path) study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:181–7. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammond D, Reid JL, Cole AG, et al. Electronic cigarette use and smoking initiation among youth: a longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ 2017;189:E1328–36. 10.1503/cmaj.161002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conner M, Grogan S, Simms-Ellis R, et al. Do electronic cigarettes increase cigarette smoking in UK adolescents? Evidence from a 12-month prospective study. Tobacco Control 2018;27:365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Auf R, Trepka MJ, Selim M, et al. E-Cigarette use is associated with other tobacco use among US adolescents. Int J Public Health 2019;64:125–34. 10.1007/s00038-018-1166-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morgenstern M, Nies A, Goecke M, et al. E-cigarettes and the use of conventional cigarettes. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018;115:243–8. 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore GF, Littlecott HJ, Moore L, et al. E-cigarette use and intentions to smoke among 10-11-year-old never-smokers in Wales. Tob Control 2016;25:147–52. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eastwood B, Dockrell MJ, Arnott D, et al. Electronic cigarette use in young people in Great Britain 2013-2014. Public Health 2015;129:1150–6. 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Lacy E, Fletcher A, Hewitt G, et al. Cross-sectional study examining the prevalence, correlates and sequencing of electronic cigarette and tobacco use among 11-16-year olds in schools in Wales. BMJ Open 2017;7:e012784. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore G, Hewitt G, Evans J, et al. Electronic-cigarette use among young people in Wales: evidence from two cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007072. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. Associations between e-cigarette access and smoking and drinking behaviours in teenagers. BMC Public Health 2015;15:244. 10.1186/s12889-015-1618-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics 2016;138 10.1542/peds.2016-0379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Byrne S, Brindal E, Williams G. E-cigarettes, smoking and health. A literature review update Australia. CSIRO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Owusu D, Huang J, Weaver SR, et al. Patterns and trends of dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2015-2018. Prev Med Rep 2019;16:101009. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.101009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rapp JL, Alpert N, Flores RM, et al. Serum cotinine levels and nicotine addiction potential of e-cigarettes: an NHANES analysis. Carcinogenesis 2020;41:1454–9. 10.1093/carcin/bgaa015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dawkins L, Munafò M, Christoforou G, et al. The effects of e-cigarette visual appearance on craving and withdrawal symptoms in abstinent smokers. Psychol Addict Behav 2016;30:101–5. 10.1037/adb0000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zare S, Nemati M, Zheng Y. A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: flavor, nicotine strength, and type. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194145. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045603supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the manuscript are from published research.