Abstract

Salient sensory environments experienced by a parental generation can exert intergenerational influences on offspring. While these data provide an exciting new perspective on biological inheritance, questions remain about causes and consequences of intergenerational influences of salient sensory experience. We previously showed that exposing male mice to a salient olfactory experience, like olfactory fear conditioning, resulted in offspring demonstrating a sensitivity to the odor used to condition the paternal generation and possessing enhanced neuroanatomical representation for that odor. In this study, we first injected RNA extracted from sperm of male mice that underwent olfactory fear conditioning into naïve single-cell zygotes and found that adults that developed from these embryos had increased sensitivity and enhanced neuroanatomical representation for the odor (Odor A) with which the paternal male had been conditioned. Next, we found that female, but not male offspring sired by males conditioned with Odor A show enhanced consolidation of a weak single-trial Odor A + shock fear conditioning protocol. Our data provide evidence that RNA found in the paternal germline after exposure to salient sensory experiences can contribute to intergenerational influences of such experiences, and that such intergenerational influences confer an element of adaptation to the offspring. In so doing, our study of intergenerational influences of parental sensory experience adds to existing literature on intergenerational influences of parental exposures to stress and dietary manipulations and suggests that some causes (sperm RNA) and consequences (behavioral flexibility) of intergenerational influences of parental experiences may be conserved across a variety of parental experiences.

Keywords: adaptation, conditioning, legacies, neuroanatomy, olfaction, RNA, stress

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Sensory cues abound in the umwelt of an organism. Appropriate responses to physical and chemical stimuli in the environment are crucial for an organism to function optimally and survive. While such responses are influenced by experiences that come to be associated with these stimuli, accumulating evidence suggests that the legacy of parental experiences with stimuli can significantly shape responses in future generations. Organisms mount defense responses to physical and chemical cues from predators, but the development of such responses can arise de novo during development as a consequence of parental exposure to these same predators.1,2 Environmental insults like droughts, endocrine disruptors and dietary manipulations influence responses of offspring in both plants and animals even with the offspring not directly experiencing the insults.3–7 In addition, offspring of a variety of species ranging from humans to mice exhibit a preference for the odors of foods consumed by mothers during pregnancy or lactation.8–10 These data are representative of a burgeoning field of research that suggests the profound influence that salient sensory environments exert on future generations. However, despite an appreciation for this phenomenon of intergenerational influences of salient sensory events, very little is known about how information about salient sensory cues is inherited via the parental gametes and the consequences of this inheritance on the physiology and behavior of offspring.

The olfactory system is an ideal system to successfully address how experience with a salient environmental cue can exert influences across generations.11–19 Training mice to associate a specific odor (eg, Odor A) with a mild foot-shock results in these mice developing fearful behavior toward Odor A and possessing increased neuroanatomical expression of odorant receptors that detect Odor A.20,21 From an intergenerational perspective, we have demonstrated that after mice have been exposed to Odor A + shock conditioning their naïve offspring possess a sensitivity to Odor A and increased neuroanatomical expression of odorant receptors that detect Odor A.22,23 Ours are not the only studies to have reported intergenerational imprints of parental olfactory experience. Olfactory conditioning of fruit-flies influences the behavior of offspring.24 Appetitive and adverse maternal experience with odors in rodents is transmitted to neonatal pups thereby impacting the neuroanatomy, physiology and behavior of the pups when they detect that odor.10,12 Odor-based learning has been shown to have intergenerational effects in offspring.25 Most recently, the effects of aversive taste conditioning in a parental generation have been reported to persist in at least four generations of worms.26 Building on our studies using olfactory fear conditioning in a parental generation of mice and examining influences in offspring, we ask how intergenerational influences of salient olfactory experiences can be inherited across generations and what consequence such influences have on the behavior of the offspring as they navigate their own umwelts.

RNA found in sperm of male rodents has been shown to mediate intergenerational influences of paternal stress and dietary manipulations.27–31 Therefore, we examined whether RNA found in the sperm of male mice exposed to olfactory fear conditioning played any role in intergenerational influences of salient olfactory experience. To do so, we first injected RNA obtained from sperm of male mice exposed to olfactory fear conditioning with Odor A into naïve single-cell zygotes and measured olfactory sensitivity and olfactory neuroanatomy related to Odor A in adulthood. In terms of consequence, while intergenerational influences of salient parental environments have traditionally been thought to constrain biology in offspring, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that such influences can afford behavioral flexibility to offspring and be adaptive. To examine this possibility in the context of salient sensory experiences, male mice first underwent olfactory fear conditioning with Odor A and then learning and memory in their offspring was measured after conditioning the offspring to Odor A or B.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Animals

Experiments were conducted with 2 to 3 months old sexually and odor-inexperienced animals. C57BL/6J animals, M71-LacZ animals maintained in mixed 129/Sv × C57Bl/6J background, and MOR23-GFP animals maintained in mixed 129/Sv × C57Bl/6J background were bred in the Yerkes Neuroscience animal facility. Animals were housed on a 12 hours light/dark cycle in standard groups cages (5/cage) with ad libitum access to food and water, with all experiments conducted during the light half of the cycle. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University, and followed guidelines set by the National Institute of Health.

2.2 |. Experiments related to determining causes of intergenerational influences of salient olfactory experience

2.2.1 |. Olfactory treatment of parental F0 generation

F0-trained:

Males were trained to associate acetophenone or Lyral presentation with mild foot-shocks. For this purpose, the startle-response system (SR-LAB, San Diego Instruments) was modified to deliver discrete odor stimuli. The animals were trained on three consecutive days with each training day consisting of five trials of odor presentation for 10 seconds co-terminating with a 0.25 second 0.4 mA foot-shock with an average inter-trial interval of 120 seconds. Both acetophenone and Lyral (from Sigma, and IFF, respectively) were used at a 10% concentration diluted with propylene glycol. These odors were chosen based on prior work that demonstrated that the M71 odorant receptor is activated by acetophenone, and that the MOR23 odorant receptor is activated by Lyral.14,19,32 F0-exposed-males were treated like the F0-trained group with the main important exception that odor presentations were not accompanied by any foot-shocks.

2.2.2 |. Sperm collection from F0 males and RNA extraction from sperm

Sperm was collected from F0-exposed or F0-trained mice that were treated with either acetophenone or Lyral using pure sperm reagents. Sperm from three mice of the same F0 treatment condition were pooled. A total of 21 males were used per group, with an n of 7/group after pooling. See Supplementary Material for more details. RNA was extracted from sperm that was collected following the TRIzol procedure (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). The concentration was measured using Qubit and adjusted to 1 ng/μL before injection into zygote.

2.2.3 |. Isolation of zygotes, RNA microinjection and embryo transfer

Single-cell zygotes were collected post-mortem for microinjection of RNA contained in sperm of treated F0 males (see Supplementary Material for details). The zygotes were cultured in potassium-supplemented simplex optimized medium (KSOM, EMD Millipore) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator and then injected using a microinjector setup (XenoWorks Micromanipulator and Digital Microinjector by Shutter Instruments). The RNA was injected into the male pronucleus. The swelling of the pronucleus was used as an indication of a successful microinjection. The zygotes were cultured overnight in KSOM (EMD Millipore) covered with mineral oil and incubated in an incubator maintained at 37°C and with 5% CO2. Embryo development was accessed 1 day later by visualizing whether the zygotes reached the two-cell stage. Genotype of the zygotes was M71-LacZ/+;MOR23-GFP/+. Two-cell embryos (10–20 in number) were unilaterally transferred into the oviduct of a pseudo-pregnant female (see Supplementary Materials for details).

2.2.4 |. Odor-potentiated startle of injected zygotes in adulthood (F1 offspring)

We measured baseline behavioral sensitivity of adult mice derived from RNA-injected zygotes to odors using an odor potentiated startle (OPS) behavioral assay that we and others have used previously22,23,33 and that measures acoustic startle response to a noise burst. Animals were habituated to the startle chambers for 5–10 minutes on three separate days. On the day of testing, animals were first exposed to 15 Startle-alone (105 dB noise burst) trials (Leaders), before being presented with 10 odor+startle trials randomly intermingled with 10 startle-alone trials. The odor+startle trials consisted of a 10 seconds odor presentation co-terminating with a 50 msec 105 db noise burst. For each animal, an OPS score was computed by subtracting the startle response in the first odor+startle trial from the startle response in the last startle-alone leader. This OPS score was then divided by the last startle alone leader and multiplied by 100 to yield the percent OPS score (% OPS) reported in the results. Just like prior interpretations of this assay, we view higher % OPS readings as an indication of an increased sensitivity to the odor tested.

2.2.5 |. Neuroanatomy on F1 olfactory bulb and main olfactory epithelium

β-galactosidase staining:

Brains were rapidly dissected and placed into 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, after which they were washed three times in 1X PBS for 5 minutes each time. M71-LacZ was stained for β-galactosidase, using 45 mg of X-gal (1 mg/mL) dissolved in 600 μL of DMSO and 45 mL of a solution of 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 2 mM MgCl in 1X PBS, and incubated at 37°C for 3 hours.

Measurement of M71-LacZ glomerular area in the olfactory bulb:

A microscope-mounted digital camera was used to capture high-resolution images of the β-galactosidase stained M71 glomeruli at ×40 magnification. Each glomerulus was traced using the lasso tool in photoshop and the area was recorded from the histogram tool. No animals were excluded from analysis unless the olfactory bulbs were damaged and this resulted in uneven numbers analyzed across dorsal and medial glomeruli. See Supplementary Material for more details.

Western blotting:

10 μL of protease cocktail inhibitor mix from Sigma (Cat# P8340) was mixed with 1 mL of RIPA cell lysis buffer and 500 μL of this mixture was added to a tube containing a fresh frozen main olfactory epithelium (MOE). The MOE was homogenized in this mixture using a plastic pestle and then an electric homogenizer. The tissue was then placed on a shaker for 15 minutes at 4°C to ensure complete lysis. The lysate was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 12 000 rpm. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube on ice. Amount of protein in the lysate was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit. Standard SDS-PAGE was performed using 15 to 40 μg of protein per sample. After gel electrophoresis and transfer of the protein to nitrocellulose membrane, the blots were probed with primary antibody (details noted below), the antibody detected by a peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody and signal detected using ECL substrate (Super Signal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate) and a BioRad Chemidoc MP-Imaging system.

Detecting LacZ:

Primary antibody—mouse anti-LacZ (Cat # 40-1a) from developmental studies Hybridoma Bank; 1:200 dilutions with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in ×1 TBS-0.1% Tween20, overnight on a rocker at 4°C. Secondary antibody-anti mouse HRP, Cat # 7076S (Cell Signaling); 1:2000 dilution with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in ×1 TBS-0.1% Tween20, 1 hour at room temperature.

Detecting GFP:

Primary antibody-rabbit anti-GFP (ab6556) from Abcam; 1:2500 dilutions with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in ×1 TB S-0.1% Tween20, overnight on a rocker at 4°C. Secondary antibody-anti rabbit HRP; Cat # 7074S (Cell Signaling) 1:2000 dilution with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in 1X TBS-0.1% tween 20, 1 hour at room temperature.

Detecting β-actin as a loading control: Primary antibody-anti-Beta Actin (8H10D10) from Cell Signaling technology, dilution 1:5000 with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in 1X TB S-0.1% Tween20, 1 hour at room temperature. Secondary Antibody - Secondary Antibody: Anti mouse HRP, Cat # 7076S (Cell Signaling); 1:2000 dilution with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in 1X TBS-0.1% Tween20, 1 hour at room temperature.

The amount of protein in every sample was quantified relative to β-actin by performing optical density measurements using ImageJ.

2.3 |. Experiments related to determining consequences of intergenerational influences of salient olfactory experience (Figure S7)

2.3.1 |. Olfactory treatment of parental F0 generation

C57BL/6J males were treated as noted above. Ten days later, each F0-trained or F0-exposed male was mated with naïve C57BL/6J female mice. Thirteen days later, animals were separated to prevent any interaction between the males and their offspring.

2.3.2 |. Testing for altered threshold for learning in the F1 generation

F1 generation adult mice were habituated for 1 day to the San Diego Instruments testing chambers. One day later, mice were trained to associate a single 10 seconds acetophenone or Lyral odor presentation with a co-terminating 0.25 second 0.6 mA foot-shock. Both acetophenone and Lyral (from Sigma, and IFF, respectively) were used at a 10% concentration diluted with propylene glycol. The next day, animals were habituated to a completely different context, Mouse Habitest Chambers (Coulbourn Instruments). Finally, 1 day later in the Mouse Habitest Chambers animals were exposed to 7 minutes of air followed by a 30-second presentation of acetophenone or Lyral, and another 7 minutes of air. As a measure of learning and consolidating memory about the single-trial olfactory fear conditioning, freezing behavior prior and in response to the odor presentation was recorded and analyzed using the FreezeFrame software. Our pilot experiments demonstrated that the single-trial olfactory fear conditioning was a weak conditioning protocol that resulted in baseline levels of freezing to the odor during the testing session allowing us to examine any augmentation of learning and memory as a consequence of a preexisting sensitivity to the F0 conditioning odor.

2.3.3 |. Small RNA sequencing from sperm of F0-exposed and F0-trained males

After pure sperm were collected from F0-exposed and F0-trained males, small RNA were isolated using the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). Samples were then sequenced by Exiqon (Denmark) yielding an average read depth of 20 million reads/sample. Differential expression was assessed by Exiqon using the Edge R statistical software pipeline (Bioconductor, http://www.bioconductor.org). Transcripts showing evidence of expression abundance differences across our two groups (P < .05) were used for downstream pathway analysis with Metacore. Metacore was run with default settings.

2.4 |. Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in R 3.5.2. Non-independence in the data, because of multiple animals from the same litter being included in the analyses, was addressed by taking the average per litter and using this value for statistical testing and effect size calculation. Visual inspection of the distributions of litter averages clearly showed deviation from normality and hence non-parametric tests (permutation tests) were used for statistical inference and a robust version of Cohen’s D (dR)34 was used for effect size estimation.

Regarding the permutation tests, we generated null distributions by multiple times randomly assigning litter averages to one of the investigated treatment groups, without replacement. We addressed sex as a biological variable in our studies by measuring treatment into sex interaction effects. These analyses provide a direct statistical comparison between the treatment effect sizes in males and females. Where the interaction was not significant, we collapsed the data across sexes and report data pooled across the sexes. In cases, where treatment into sex interaction was significant, we report sex-specific data. Analyses like these have been recommended to address sex as a biological variable.35 However, to be transparent with our data, in our supplementary material, we also report statistics on the data separated by sex while also using individual color points to denote animals from the same litter. For interaction effects, investigating how treatment effects differ across males and females, the “Unrestricted permutation of observations” approach36 was adopted. For each permutation, a F-statistic was calculated using the aov (ANOVA) function in R. This procedure was repeated 100 000 times and the P-value was calculated as the proportion of permuted F-values exceeding the initially observed value.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Injection of RNA found in sperm of F0-odor A-trained males into naïve zygotes increases behavioral sensitivity to odor A in adulthood

F0-Ace treatment:

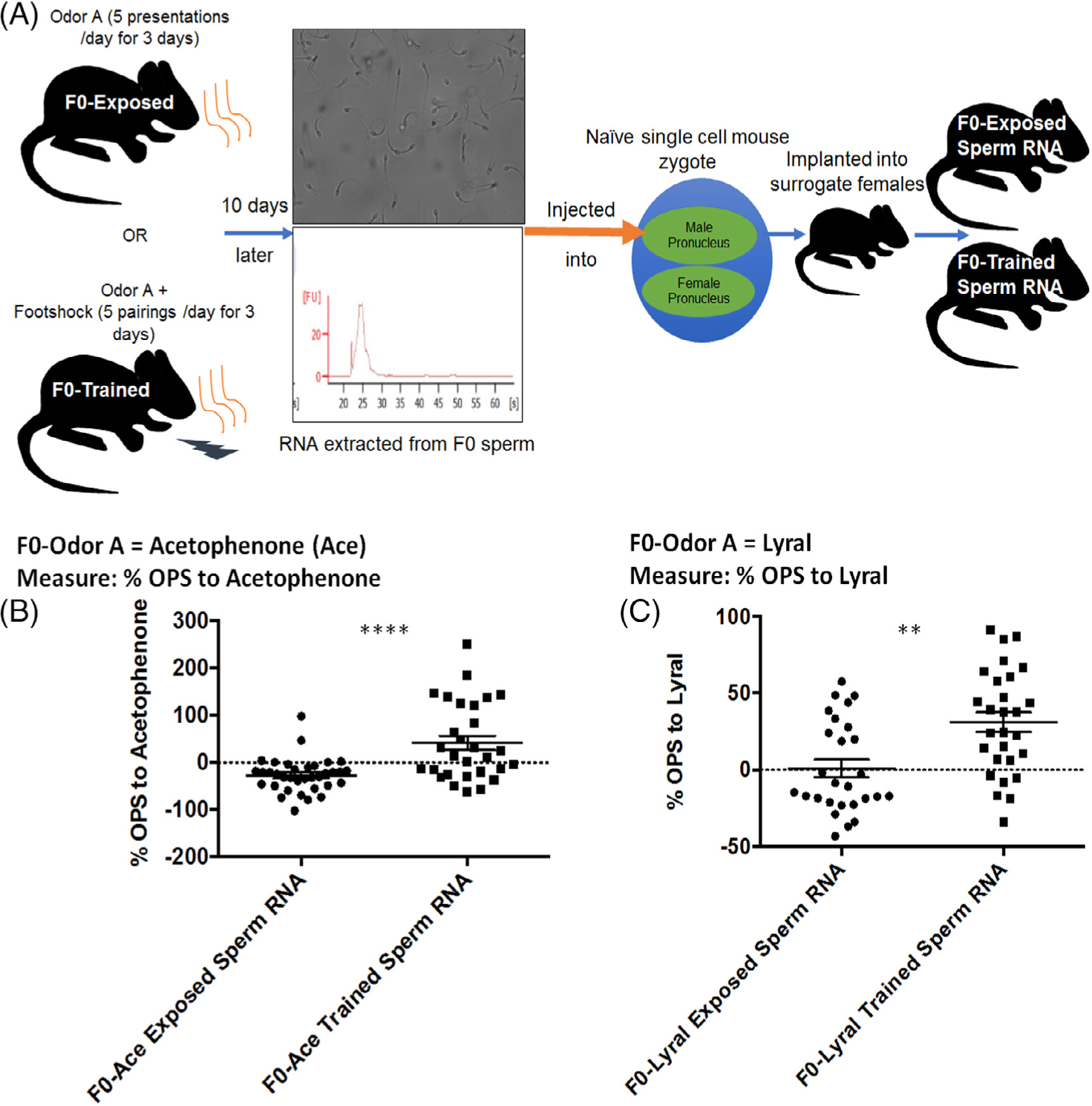

Injecting RNA extracted from sperm of F0-Ace-trained-M71LacZ males into naïve single-cell zygotes increased behavioral sensitivity of female and male animals to Acetophenone in adulthood (F0-Ace-trained-sperm RNA) compared with the behavioral sensitivity to acetophenone measured in female and male animals that developed from zygotes injected with RNA extracted from sperm of F0-Ace-exposed-M71LacZ males (F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA). (Interaction effect: F = .437, P = .52. Sexes pooled: F = 13.111, P < .0001, dR = 1.176) (Figure 1A, B). Sex-specific data shown in Figure S1.

FIGURE 1.

Sperm RNA contributes to behavioral imprints of salient olfactory experiences across generations. (A) Experimental design to determine the contribution of sperm RNA to behavioral and neuroanatomical influences of salient paternal olfactory experiences across generations. Male mice were either exposed to an odor (eg, Odor A) (F0-exposed group) or odor A presentations were paired with mild foot-shocks (F0-trained group). Ten days later, pure sperm were collected post-mortem and RNA was extracted from these sperm. Representative image of sperm and RNA bioanalyzer trace shown. These RNA from sperm of F0-exposed or F0-trained males were then injected into the male pronucleus of naïve single cell mouse zygotes. The zygotes were implanted into surrogate female mice and experiments were performed on the resultant offspring at 2-months of age. (B) Sensitivity to acetophenone (Ace) after zygotes injected with RNA from sperm of F0 males that were treated with Ace. Male and female mice that developed from zygotes into which RNA from sperm of F0-Ace-trained males had been injected (F0-Ace-trained-sperm RNA: 30 animals, 12 litters) have a higher sensitivity to Acetophenone compared with mice that developed from zygotes into which RNA from sperm of F0-Ace-exposed males had been injected (F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA: 36 animals, 13 litters). (C) Sensitivity to Lyral after zygotes injected with RNA from sperm of F0 males that were treated with Lyral. Male and female mice that developed from zygotes into which RNA from sperm of F0-Lyral trained males had been injected (F0-Lyral trained sperm RNA: 28 animals, 11 litters) have a higher sensitivity to Lyral compared with mice that developed from zygotes into which RNA from sperm of F0-Lyral exposed males had been injected (F0-Lyral exposed sperm RNA: 27 animals, 13 litters). Data presented as mean ± SEM. **P < .01, **** P < .0001

F0-Lyral treatment:

Injecting RNA extracted from sperm of F0-Lyrai-trained-MOR23GFP males into naïve single-cell zygotes increased behavioral sensitivity of female and male animals to Lyral in adulthood (F0-Lyral trained sperm RNA) compared with the behavioral sensitivity to Lyral measured in female and male animals that developed from zygotes injected with RNA extracted from sperm of F0-Lyral-exposed-MOR23GFP males (F0-Lyral exposed sperm RNA). (Interaction effect: F = 0.484, P = .49. Sexes pooled: F = 11.079, P = .0034, dR = 1.405) (Figure 1A, C). Sex-specific data shown in Figure S1.

3.2 |. Injection of RNA found in sperm of F0-OdorA-trained males into naïve zygotes enhances representation of Odor A-related neuroanatomy in the adult olfactory system

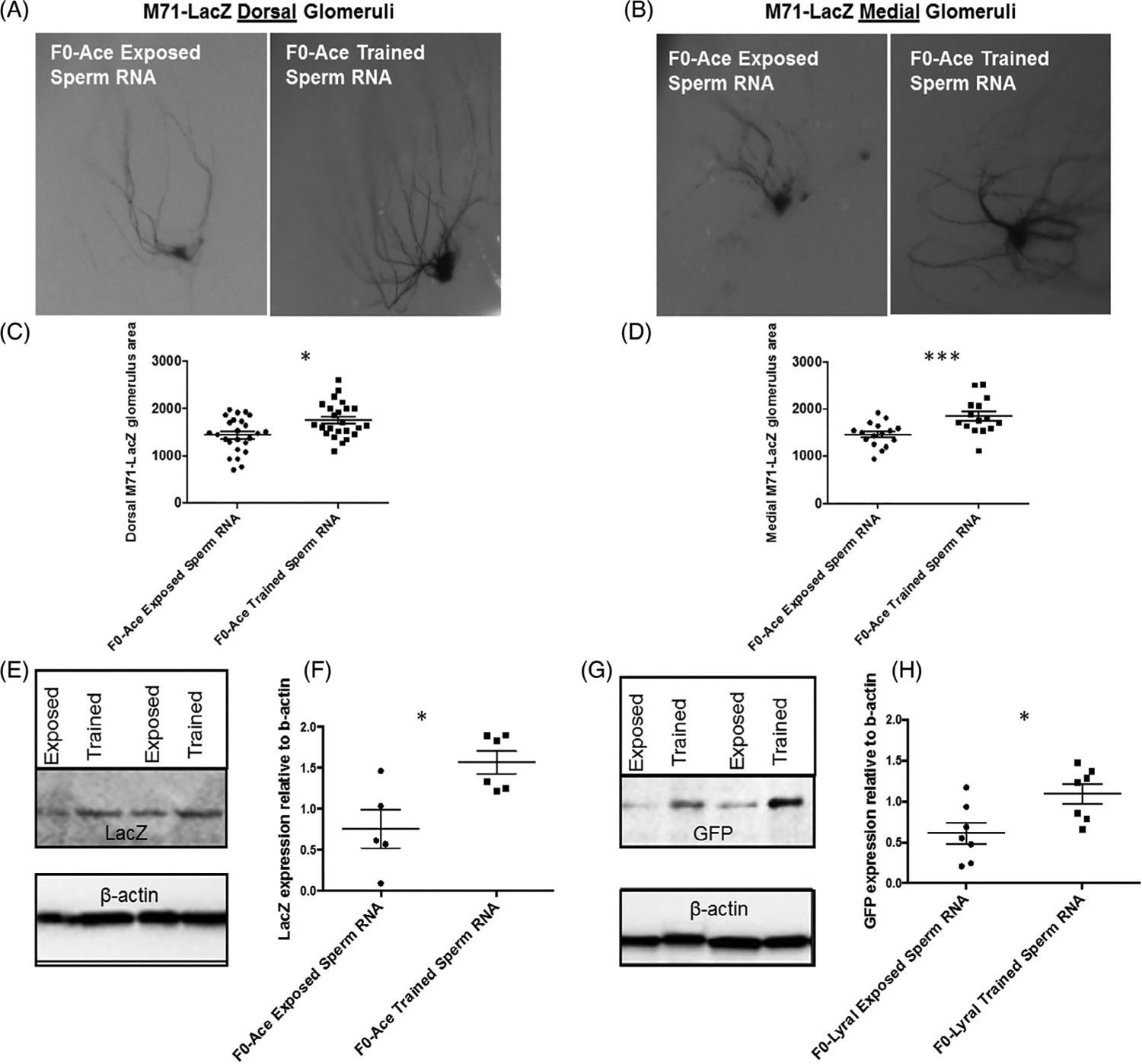

F0-Ace treatment:

Adult female and male F0-Ace-trained-sperm RNA mice had larger M71-LacZ glomeruli in adulthood compared with adult F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA mice. (Dorsal glomeruli: interaction effect: F = 0.005, P = .94. Sexes pooled: F = 5.152, P = .03, dR = .652) (Medial glomeruli: Interaction effect: F = 2.272, P = .15. Sexes pooled: F = 23.015, P = .0003, dR = 1.673) (Figure 2A–D). Sex-specific data shown in Figure S2. To ensure another measure of OR expression in the MOE of adult mice developing from zygotes that had been injected with RNA extracted from sperm of Acetophenone-treated F0 males, we performed western blotting on M71-LacZ MOE with a LacZ antibody that we have validated for its efficacy in detecting LacZ staining (Figure S3A). This approach revealed that F0-Ace-trained-sperm RNA animals had higher LacZ expression in the MOE than F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA (F = 9.884, P = .015, dR = 1.811) (Figure 2E,F) (full blots shown in Figure S4). To account for the potential that our enhancements in M71-LacZ protein expression were a result of regulation of transgene expression and not reflective of regulation of the endogenous genomic loci, we performed RT-qPCR on RNA extracted from the MOE, for the gene encoding acetophenone-responsive odorant receptor (olfr160) and the gene encoding the Lyral-responsive odorant receptor (olfr16). We found that that F0-Ace-trained-sperm RNA animals had higher olfr160 mRNA expression in the MOE than F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA (t = 2.414, P = .04) (Figure S5A). We did not find differences in olfr16 mRNA levels in the MOE across groups (Figure S5B).

FIGURE 2.

Sperm RNA contributes to neuroanatomical imprints of salient olfactory experiences across generations. (A-D) β-galactosidase staining shows that mice that developed from zygotes into which RNA from sperm of F0-Ace-trained males had been injected (F0-Ace-trained sperm RNA) have larger dorsal and medial M71-LacZ Ace-responsive glomeruli compared with mice that developed from zygotes into which RNA from sperm of F0-Ace-exposed males had been injected (F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA) (F0-Ace-exposed-sperm RNA: Dorsal Glomeruli −25 animals, 12 litters. Medial glomeruli—20 animals, 10 litters) (F0-Ace-trained-sperm RNA: dorsal glomeruli - 24 animals, 11 litters. Medial glomeruli - 15 animals, 9 litters). (E,F) Quantitation of LacZ expression in the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) using Western Blotting. F0-Acetrained-sperm RNA animals (n = 6, 6 litters) have higher M71-LacZ expression in the MOE compared with F0-Ace-exposed sperm RNA animals (n = 5, 5 litters). Partial blots shown, full blots shown in Figure S4. (G,H) Quantitation of GFP expression in the MOE using Western Blotting. F0-Lyral trained sperm RNA animals (n = 7, 7 litters) have higher MOR23-GFP expression in the MOE compared with F0-Lyral exposed sperm RNA animals (n = 7, 7 litters). Partial blots shown, full blots shown in Figure S6. Data presented as mean ± SEM. * P < .05, *** P < .001

F0-Lyral treatment:

Due to the position of MOR23-GFP glomeruli on the olfactory bulb it is challenging to visualize and quantitate their size and instead we used western blotting to measure the GFP levels as we have performed in our previous publication22 (Figure S3B). We found a significant increase in GFP expression in the MOE of F1-trained Lyral F0 sperm RNA animals compared with F1-exposed Lyral F0 sperm RNA animals (F = 7.19, P = .021, dR = 1.201) (Figure 2G,H) (full blots shown in Figure S6). To account for the potential that our enhancements in MOR23-GFP protein expression were a result of regulation of transgene expression and not reflective of regulation of the endogenous genomic loci, we performed RT-qPCR on RNA extracted from the MOE, for olfr160 and olfr16. We did not find differences in olfr160 mRNA levels in the MOE across groups (Figure S5C). Instead, we found that F0-Lyral trained sperm RNA animals had higher olfr16 mRNA expression in the MOE than F0-Lyral exposed sperm RNA (t = 2.800, P = .023) (Figure S5D).

3.3 |. Female offspring of F0-OdorA-trained males show enhanced consolidation of weak single-trial odor A+ shock fear conditioning

F0-Ace treatment:

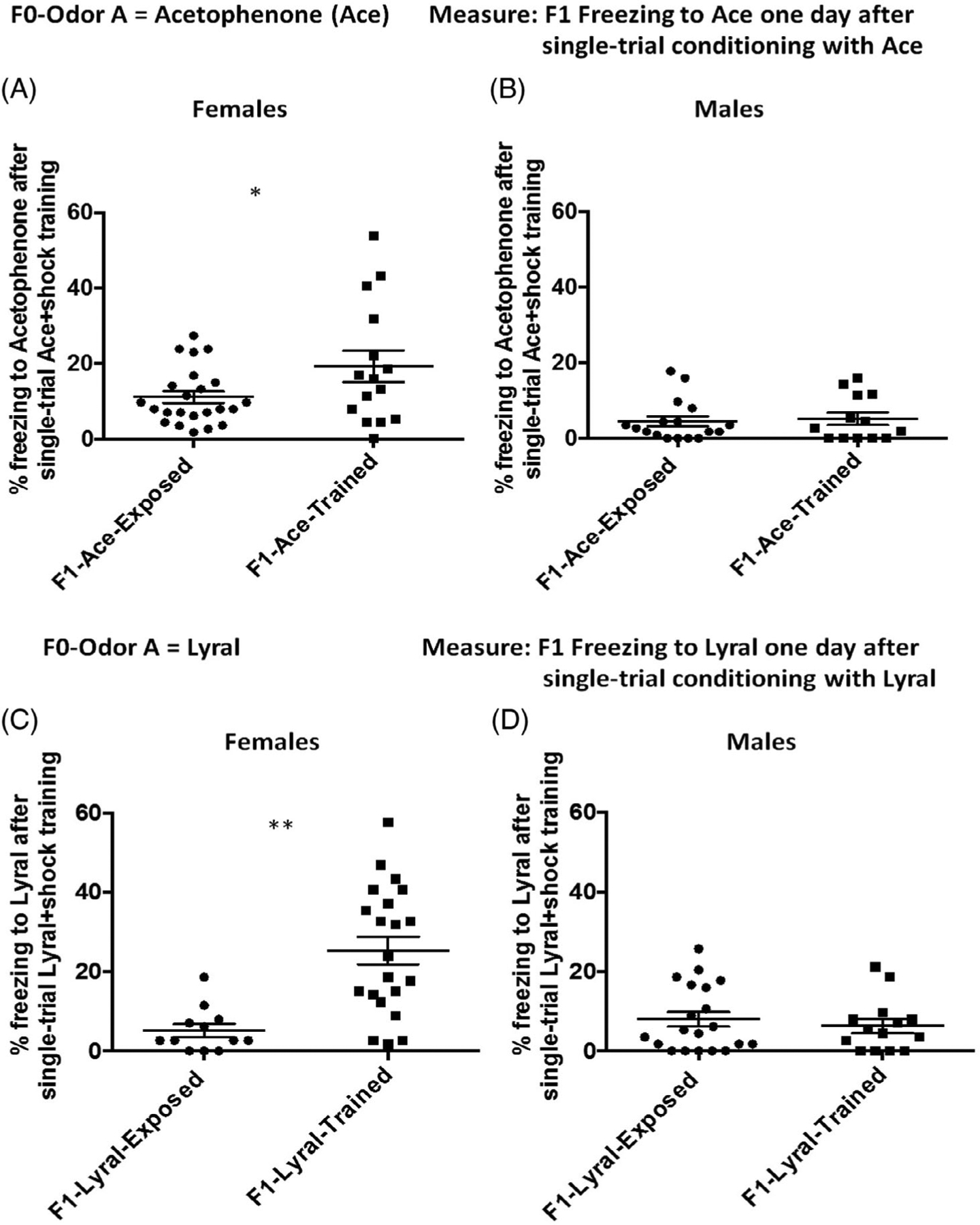

F1-Ace-exposed and F1-Ace-trained mice were fear conditioned to acetophenone using a weak single-trial fear conditioning protocol wherein a single acetophenone presentation was paired with a mild foot-shock in Context A. One day later, F1-Acetrained female, but not male mice showed increased freezing to the acetophenone presentation in Context B compared with F1-Aceexposed animals (interaction effect: F = 3.754, P = .065. Female mice: F = 4.936, P = .045, dR = .615. Male mice F = 0.524, P = .73, dR = 0.163) (Figures S7 and Figure 3A, 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Parental sensory experience facilitates sensory learning in offspring. (A,B) Salient experience with Ace facilitates sensory learning about Ace in female offspring. Female (A) but not male (B) offspring sired by F0-Ace-trained males (F1-Ace-trained) show higher consolidation of single trial Ace+shock conditioning compared with female offspring sired by F0-Ace-exposed males (F1-Ace-exposed) (F1-Ace-exposed: females n = 23, 10 litters, males n = 17, 5 litters.) (F1-Ace-trained: females n = 15, 7 litters. Males n = 13, 5 litters.). (C,D) Salient experience with Lyral facilitates sensory learning about Lyral in female offspring. Female (C) but not male (D) offspring sired by F0-Lyral trained males (F1-Lyral-trained) show higher consolidation of single trial Lyral +shock conditioning compared with female offspring sired by F0-Lyral exposed males (F1-Lyral-exposed). (F1-Lyral-exposed: females n = 12, 5 litters. Males n = 20, 6 litters.) (F1-Lyral-trained: females n = 21, 5 litters. Males n = 15, 5 litters.). Data presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05, **P < .01

F0-Lyral treatment:

F1-Lyral-exposed and F1-Lyral-trained mice were fear conditioned to Lyral using a weak single-trial fear conditioning protocol wherein a single Lyral presentation was paired with a mild foot-shock in Context A. One day later, F1-Lyral-trained female, but not male mice showed increased freezing to the Lyral presentation in Context B compared with F1-Lyral-exposed animals (interaction effect: F = 13.82, P = .001. Female mice: F = 16.163, P < .001, dR = 1.391. Male mice F = 0.524, P = .68, dR = −0.10) (Figures S7, and Figure 3C, 3D).

Offspring of F0-OdorA-trained males did not show enhanced consolidation of weak single-trial Odor B+ shock fear conditioning (Figure S8).

3.4 |. miRNA-seq of F0 sperm RNA reveal differential expression of miRNA related to cell growth and response to chemical stimuli

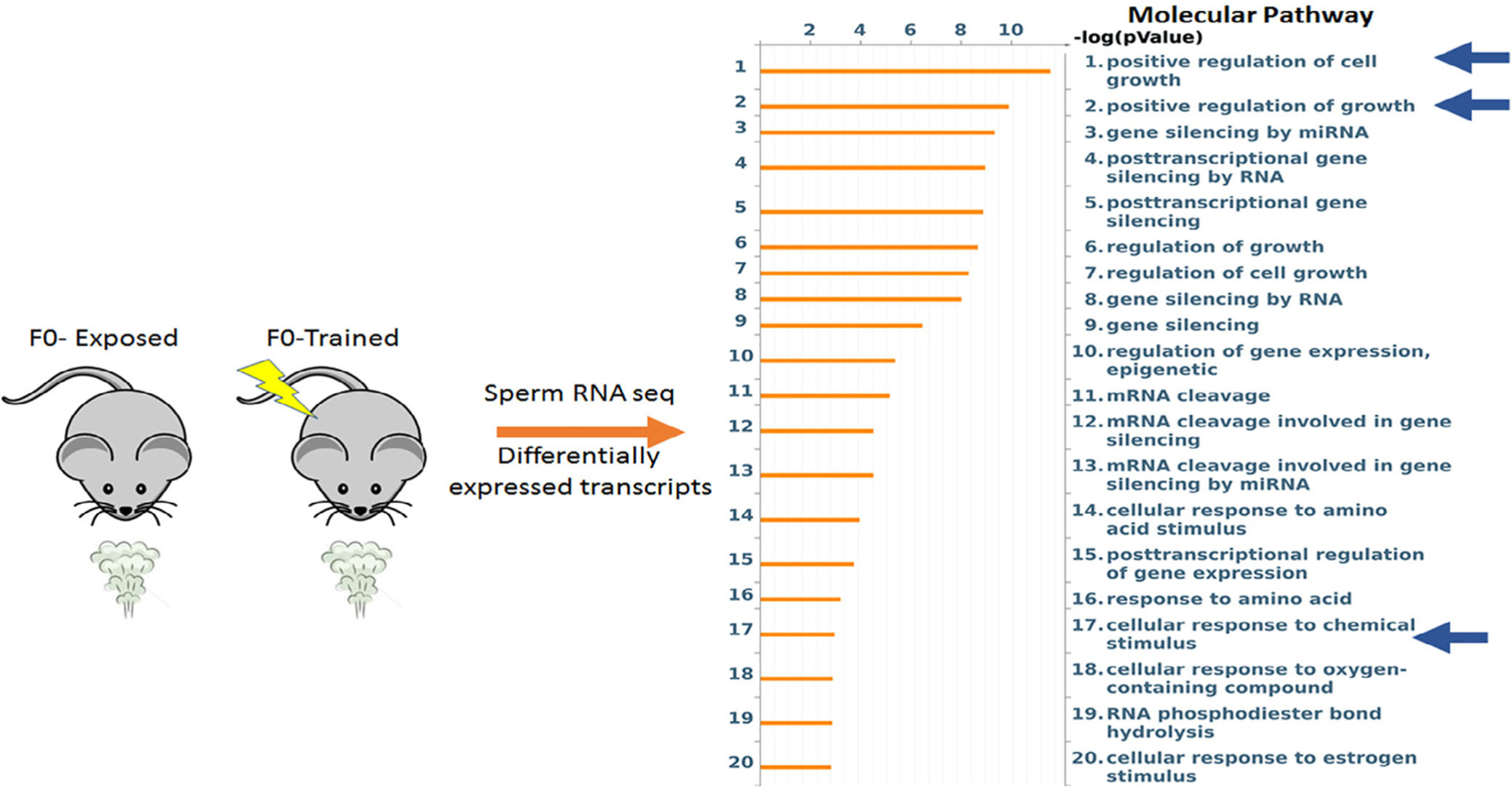

Pathway analysis of data obtained from small RNA-seq conducted on F0-trained and F0-exposed sperm RNA revealed that the miRNA that were differentially expressed between the groups targeted processes like regulation of cell growth, cellular response to chemical stimulus and cellular response to amino acid stimulus (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

miRNA expression profiling of F0-exposed and F0-trained sperm reveals alterations in miRNA that affect cell growth and cellular responses to chemical stimuli. miRNA in sperm of F0-exposed (n = 4) and F0-trained (n = 4) male mice were sequenced. Transcripts showing expression differences between the two groups (P < .05) were analyzed using default settings in MetaCore’s pathway analysis module. This analysis identified multiple molecular pathways including processes like regulation of cell growth, cellular response to chemical stimulus and cellular response to amino acid stimulus. All these processes are extremely relevant to the findings of enhanced behavioral sensitivity to odors and enhanced olfactory neuroanatomy that we report in the animals that developed from zygotes into which F0-trained or F0-exposed sperm RNA had been injected

4 |. DISCUSSION

Using the framework provided by olfactory fear conditioning, our data provide evidence that intergenerational influences of salient sensory experiences can be mediated in part by RNA found in the parental male germline, and one consequence of such influence is to bias future learning about the sensory cues with which the parental generation had a salient experience.

Across species, experiences with sensory stimuli influence neuroanatomy, gene expression, physiology and behavior in the organism directly exposed to salient sensory stimuli.37–39 It is becoming increasingly appreciated that the effects of parental exposure to salient sensory stimuli extend into offspring. Many cases of such intergenerational influences of sensory environments arise via social transmission through maternal behavior12 and via the transfer of chemical cues across maternal-fetal barriers or egg barriers in viviparous or oviparous species, respectively.8,9,40 While there is accumulating evidence that intergenerational influences of sensory environments are observed in offspring of worms, fruit flies and mice that were not conceived at the time of parental exposure to salient sensory stimuli,22–26 mechanisms underlying these influences are unknown. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to show that RNA found in the male germline of mammals exposed to salient olfactory experience can contribute to impacting olfactory-related neuroanatomy and function in future generations. While we show that RNA contained in sperm of Odor A-trained F0 male mice renders adults generated from embryos into which they are injected, more sensitive to Odor A and possessing enhanced neuroanatomy for Odor A, we do not know if there is a general enhanced sensitivity to other odors (eg, Odor B) or enhancements in olfactory neuroanatomy that respond to Odor B. Our analyses are performed on zygotes that are heterozygous for the transgenes (M71-LacZ/+; MOR23-GFP/+). While we cannot be certain which allele we are measuring via our qPCR analyses, our analyses of protein and mRNA levels captures a readout (albeit, an incomplete one) of both, transgene and non-transgene expression. The congruence in the directionality of enhanced olfactory neuroanatomy that we observed across these levels gives us confidence in our neuroanatomical data.

Given that RNA contained in sperm have been demonstrated to be important contributors to intergenerational influences of paternal dietary manipulations and paternal stress exposure in rodents,27–31 our work provides further evidence for germline RNA playing an important role in intergenerational influences of salient paternal environments, and novel evidence for their role in intergenerational influences of sensory experiences. A variety of RNA species in sperm-like tRNA-fragments,27,31 microRNA30 and long RNA29 have been shown to orchestrate intergenerational influences of stressors and our future efforts will need to address how RNA in sperm are responsible for the intergenerational influences of salient sensory experiences. As a first step toward this, we sequenced miRNA in sperm of F0-exposed and F0-trained sperm. Pathways analysis of transcripts showing evidence of expression abundance differences across our two groups (P < .05) identified multiple molecular pathways including processes like regulation of cell growth, cellular response to chemical stimulus and cellular response to amino acid stimulus, all of which are relevant for the data that we report (Figure 4). It is important to point out that we did not find any specific miRNA(s) that would explain the specific regulation of the M71 or MOR23 receptors that we focus on in our work. Future studies on how specific non-coding sperm RNA may alter the development of the olfactory system as the fertilized embryo develops will provide a more nuanced mechanistic understanding of intergenerational influences of salient sensory experiences. Additionally, sequencing all varieties of sperm RNA and not just focusing on small non-coding RNAs might provide clues about the regulation of genes encoding the specific olfactory receptors that are the subject of this work.

In our previous studies,22,23 we reported alterations in DNA methylation at odorant receptor loci of the F0 sperm genome. As we noted in those publications, we did not subscribe to the view that these changes in methylation were in any way causal to the effects in offspring but rather discussed these alterations as evidence for the germline registering a salient environmental experience. In so doing, we view our previously reported DNA methylation data to be independent of our currently reported causal influence of sperm RNA. If and how these two mechanisms by which gene expression is regulated interact at the level of the germline is a topic for future study.

Intergenerational influences of salient parental environments typically conjure up the idea that they place offspring at risk for neuropsychiatric disorders and an inability to cope with environmental challenges.41–43 In contrast, intergenerational influences of salient parental environments can confer adaptive flexibility to the offspring that enables them to thrive in the face of environmental challenges.44 Stress exposure to a parental generation of mice confers behavioral flexibility to offspring across a variety of behavioral tasks.45 High levels of cocaine self-administration in rats confers upon the next generation, a lower propensity to abuse cocaine.46 Raising gravid female crickets in a predator-rich environment results in the offspring showing an avoidance of predator-related cues in adulthood.40 In keeping with this sentiment, our data also suggest an adaptive element to the behavioral sensitivity of F1 offspring to Odor A that we have previously demonstrated.22,23 More specifically, our data suggest that the pre-existing sensitivity to Odor A (that we have refrained from calling fear toward Odor A in this and our previous publications) confers upon the F1 (female) offspring the ability to learn about the salience of this odor even in a context that would not promote learning. Why we observe effects only in female offspring in this task and not in male offspring is an open question for which we do not have any definitive answers and can only offer speculation. It is not uncommon to observe sex-differences in the effects of intergenerational influences of salient parental environments. Exposing parental rodents to stressors as well as dietary manipulations have been shown to affect one sex and not the other depending not only on the parental perturbation but also the task on which the offspring are tested.47–54 Therefore, once again, our data agree with the existing literature that male and female offspring may shoulder the legacy of parental stress differently and attention needs to be paid to the parental environmental experience and the dependent variable being tested in the offspring. With specific relevance to olfaction, sex differences in olfactory acuity have been reported55–57 and our observation that female but not male F1 offspring show enhanced learning about single-trial conditioning with the odor used to condition the F0 generation may be a consequence of this sex difference.

F1 offspring sired by F0 males that have been conditioned with Odor A do not show a bias in being able to consolidate memories of weak olfactory fear conditioning to Odor B (Figure S8). These data indicate a specificity as it relates to the parental sensory experience as opposed to future offspring generalizing learned responses to a broader bouquet of sensory cues. This finding is not surprising given that we find enhancement in naïve sensitivity to Odor A and not Odor B in offspring sired by males conditioned with Odor A.22 Such a parsimonious intergenerational consequence of parental sensory information may potentially be related to not becoming hypersensitive to any and all olfactory information and instead being matched to stimuli that offspring neurobiology might expect to encounter.

In summary, our data provide novel evidence that RNA in the male germline can contribute to intergenerational influences of parental sensory experiences and that one consequence of this phenomenon is allowing for adaptive responses of offspring to sensory cues when these cues are encountered under salient conditions. Our work fits into the broader landscape of studies that examine intergenerational influences of parental experiences and demonstrates that proximate mechanisms (RNA found in sperm) and consequences (adaptive responses) are conserved across parental experiences as diverse as stress exposure, dietary perturbations and sensory experiences.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Veterinary and Animal Care staff in the Yerkes Neuroscience Vivarium for animal husbandry. Funding for this study was provided to BGD by the Emory University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, the Emory Brain Health Institute, the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (YNPRC), a CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar Award, the Catherine Shropshire Hardman Fund, and R01MH120133 (NIMH). Additional funding was provided to YNPRC by the National Institutes of Health’s Office of the Director, Office of Research Infrastructure Programs P51OD011132. The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Funding information

Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Grant/Award Number: CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar Award; Emory University School of Medicine; National Institute of Mental Health, Grant/Award Number: MH120133; National Institute of Health, Grant/Award Number: ODP51OD11132

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data will be made available upon request. miRNA-seq data can be accessed via the GEO data depository (Accession #: GSE140862).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal AA. Transgenerational inductions of defences in animals and plants. Nature. 1999;401:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell AM, McGhee KE, Stein L. Effects of mothers’ and fathers’ experience with predation risk on the behavioral development of their offspring in threespined sticklebacks. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;7:28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anway MD. Epigenetic Transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science (New York, NY). 2005;308(5727): 1466–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carone BR, Fauquier L, Habib N, et al. Paternally induced transgenerational environmental reprogramming of metabolic gene expression in mammals. Cell. 2010;143(7):1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crews D, Gore AC, Hsu TS, et al. Transgenerational epigenetic imprints on mate preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(14):5942–5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatzig SV, Nuppenau J-N, Snowdon RJ, Schießl SV. Drought stress has transgenerational effects on seeds and seedlings in winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radford EJ, Ito M, Shi H, et al. In utero undernourishment perturbs the adult sperm methylome and intergenerational metabolism. Science (New York, NY). 2014;345(6198):1255903–1255903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaal B, Marlier L, Soussignan R. Human foetuses learn odours from their pregnant mother’s diet. Chem Senses. 2000;25(6):729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todrank J, Heth G, Restrepo D. Effects of in utero odorant exposure on neuroanatomical development of the olfactory bulb and odour preferences. Proc Royal Soc B: Biolog Sci. 2011;278(1714):1949–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65(1):175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debiec J, Sullivan RM. Intergenerational transmission of emotional trauma through amygdala-dependent mother-to-infant transfer of specific fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(33):12222–12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeMaria S, Ngai J. The cell biology of smell. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3): 443–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Y, Gong NN, Hu XS, Ni MJ, Pasi R, Matsunami H. Molecular profiling of activated olfactory neurons identifies odorant receptors for odors in vivo. Nature. 2015;18(10):1446–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kass MD, Rosenthal MC, Pottackal J, McGann JP. Fear learning enhances neural responses to threat-predictive sensory stimuli. Science (New York, NY). 2013;342(6164):1389–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nara K, Saraiva LR, Ye X, Buck LB. A large-scale analysis of odor coding in the olfactory epithelium. J Neurosci. 2011;31(25):9179–9191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan RM, Wilson DA, Ravel N, Mouly A-M. Olfactory memory networks: from emotional learning to social behaviors. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9(326):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vassalli A, Rothman A, Feinstein P, Zapotocky M, Mombaerts P. Mini-genes impart odorant receptor-specific axon guidance in the olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2002;35(4):681–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von der Weid B, Rossier D, Lindup M, et al. Large-scale transcriptional profiling of chemosensory neurons identifies receptor-ligand pairs in vivo. Nature. 2015;18(10):1455–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SV, Choi DC, Davis M, Ressler KJ. Learning-dependent structural plasticity in the adult olfactory pathway. J Neurosci. 2008;28 (49):13106–13111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison FG, Dias BG, Ressler KJ. Extinction reverses olfactory fearconditioned increases in neuron number and glomerular size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(41):12846–12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aoued HS, Sannigrahi S, Doshi N, et al. Reversing Behavioral, neuroanatomical, and Germline influences of intergenerational stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85(3):248–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dias BG, Ressler KJ. Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations. Nat Neurosci. 2013;17(1):89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams ZM. Transgenerational influence of sensorimotor training on offspring behavior and its neural basis in drosophila. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;131:166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Ge R, Zhao X, et al. Activity strengths of cortical glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons are correlated with transgenerational inheritance of learning ability. Oncotarget. 2017;8(68):112401–112416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore RS, Kaletsky R, Murphy CT. Piwi/PRG-1 Argonaute and TGF-beta mediate Transgenerational learned pathogenic avoidance. Cell. 2019;177(7):1827–1841. e1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, et al. Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science (New York, NY). 2016;351(6271):397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gapp K, Jawaid A, Sarkies P, et al. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nature. 2014;17(5):667–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gapp K, van Steenwyk G, Germain PL, et al. Alterations in sperm long RNA contribute to the epigenetic inheritance of the effects of postnatal trauma. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;41(Suppl 1):232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Leu NA, Bale TL. Transgenerational epigenetic programming via sperm microRNA recapitulates effects of paternal stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(44):13699–13704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma U, Conine CC, Shea JM, et al. Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science (New York, NY). 2016;351(6271):391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bozza T, Feinstein P, Zheng C, Mombaerts P. Odorant receptor expression defines functional units in the mouse olfactory system. J Neurosci. 2002;22(8):3033–3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hebb ALO, Zacharko RM, Gauthier M, Drolet G. Exposure of mice to a predator odor increases acoustic startle but does not disrupt the rewarding properties of VTA intracranial self-stimulation. Nature. 2003;982(2):195–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Algina J, Keselman HJ, Penfield RD. An alternative to Cohen’s standardized mean difference effect size: a robust parameter and confidence interval in the two independent groups case. Psychol Methods. 2005;10(3):317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shansky RM. Are hormones a “female problem” for animal research? Science. 2019;364(6443):825–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manly BFJ. Randomization, Bootstrap, and Monte Carlo Methods in Biology. 3rd ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lutz CC, Rodriguez-Zas SL, Fahrbach SE, Robinson GE. Transcriptional response to foraging experience in the honey bee mushroom bodies. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72(2):153–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remy J-J. Stable inheritance of an acquired behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biolog. 2010;20(20):R877–R878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Remy J-J, Hobert O. An interneuronal chemoreceptor required for olfactory imprinting in C. Science (New York, NY). 2005;309(5735): 787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storm JJ, Lima SL. Mothers forewarn offspring about predators: a transgenerational maternal effect on behavior. Am Nat. 2010;175(3): 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bohacek J, Farinelli M, Mirante O, et al. Pathological brain plasticity and cognition in the offspring of males subjected to postnatal traumatic stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(5):621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohacek J, Mansuy IM. Epigenetic inheritance of disease and disease risk. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):220–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGowan PO, Szyf M. The epigenetics of social adversity in early life: implications for mental health outcomes. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39(1): 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sih A. Effects of early stress on behavioral syndromes: an integrated adaptive perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(7):1452–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gapp K, Soldado-Magraner S, Alvarez-Sánchez M, et al. Early life stress in fathers improves behavioural flexibility in their offspring. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vassoler FM, White SL, Schmidt HD, Sadri-Vakili G, Pierce RC. Epigenetic inheritance of a cocaine-resistance phenotype. Nature Publishing Group. 2013;16(1):42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ambeskovic M, Soltanpour N, Falkenberg EA, Zucchi FCR, Kolb B, Metz GAS. Ancestral exposure to stress generates new Behavioral traits and a functional hemispheric dominance shift. Cerebral Cortex. 2017;27(3):2126–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faraji J, Karimi M, Soltanpour N, et al. Intergenerational sex-specific transmission of maternal social experience. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldstein JM, Holsen L, Handa R, Tobet S. Fetal hormonal programming of sex differences in depression: linking women’s mental health with sex differences in the brain across the lifespan. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hicks-Nelson A, Beamer G, Gurel K, Cooper R, Nephew BC. Transgenerational social stress alters immune-behavior associations and the response to vaccination. Brain Sci. 2017;7(7):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khashan AS, Abel KM, McNamee R, et al. Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell E, Klein SL, Argyropoulos KV, et al. Behavioural traits propagate across generations via segregated iterative-somatic and gametic epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):11492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mueller BR, Bale TL. Sex-specific programming of offspring emotionality after stress early in pregnancy. J Neurosci. 2008;28(36):9055–9065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulz KM, Pearson JN, Neeley EW, et al. Maternal stress during pregnancy causes sex-specific alterations in offspring memory performance, social interactions, indices of anxiety, and body mass. Physiol Behav. 2011;104(2):340–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koelega HS. Sex differences in olfactory sensitivity and the problem of the generality of smell acuity. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78(1):203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laska M, Wieser A, Salazar LTH. Sex-specific differences in olfactory sensitivity for putative human pheromones in nonhuman primates. Journal of comparative psychology (Washington, DC: 1983). 2006;120(2):106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mihalick SM, Langlois JC, Krienke JD. Strain and sex differences on olfactory discrimination learning in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice (Mus musculus). J Comp Psychol. 2000;114(4):365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.