Abstract

Objective:

Global migration and linguistic diversity are at record highs, making healthcare language barriers more prevalent. Nurses, often the first contact with patients in the healthcare system, can improve outcomes including safety and satisfaction through how they manage language barriers. This review aimed to explore how research has examined the nursing workforce with respect to language barriers.

Methods:

A systematic scoping review of the literature was conducted using four databases. An iterative coding approach was used for data analysis. Study quality was appraised using the CASP checklists.

Results:

48 studies representing 16 countries were included. Diverse healthcare settings were represented, with the inpatient setting most commonly studied. The majority of studies were qualitative. Coding produced 4 themes: (1) Interpreter Use/Misuse, (2) Barriers to and Facilitators of Quality Care, (3) Cultural Competence, and (4) Interventions.

Conclusion:

Generally, nurses noted like experiences and applied similar strategies regardless of setting, country, or language. Language barriers complicated care delivery while increasing stress and workload.

Practice Implications:

This review identified gaps which future research can investigate to better support nurses working through language barriers. Similarly, healthcare and government leaders have opportunities to enact policies which address bilingual proficiency, workload, and interpreter use.

Keywords: Nursing, Communication barriers, Culture, Language, Health care quality

1. Introduction

Global migration is making countries around the world increasingly linguistically diverse and language barriers between healthcare providers and patients more prevalent [1]. Globally, migration patterns have changed significantly in recent years, and the number of displaced people seeking refuge in foreign nations is at a record high [2]. These changing demographics challenge health systems to provide care when a language barrier is present. Language barriers affect healthcare access [3,4], patient satisfaction [5], and safety [6] and require integrating interpreter services into both the process of care delivery and the therapeutic relationship in order to minimize disparities [7]. Research about language barriers in healthcare has grown substantially in the last twenty years, but it is notably focused on physicians and lacking about nurses [8].

Since nurses are often the first professional point of contact for patients in healthcare systems, how they address language barriers at that first juncture and throughout the encounter influences patient experiences and outcomes. Research shows that managing language barriers during admission and discharge decreases length of stay [9], errors, and readmissions [10].

1.1. Objective

With these demographic and workforce trends in mind, we sought to explore how research examines the global nursing workforce facing language barriers. Goals of this study include highlighting the current state of the science and identifying gaps in the literature to make recommendations for future research around language barriers.

2. Methods

We conducted a scoping review of the literature that studied the nursing workforce with regard to language barriers. Scoping reviews address research questions with emerging evidence, where the dearth of randomized controlled trials makes other systematic review methods difficult [11]. This methodology identifies gaps in existing literature and clarifies future research questions [12,13]. With these criteria in mind, we chose to undertake a scoping review following the framework set by Arksey and O’Malley [12] to meet our goals.

2.1. Scoping review framework

The Arksey and O’Malley scoping review framework utilizes a five-stage, iterative approach [12]. In the first stages, researchers identify a research question and undertake a systematic, comprehensive search. In the study screening stage, inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied, with the possibility that criteria change as authors develop greater familiarity with the breadth of the literature. Following screening, researchers organize and sort the data to enable theme identification, often using a chart or table. While this stage can be guided by a framework which emphasizes certain aspects of the literature, uniform categorization is not always achievable due to the diversity in study design and clarity. In the final stage, the organized data is summarized and presented to illuminate the breadth of literature on a topic rather than to weight the evidence by quality or outcomes measurements.

2.2. Literature search

2.2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We began with limiting our search criteria to studies which examined language barriers in populations of registered nurses (RN), practical nurses, and nurse practitioners (NP). We excluded studies which addressed language barriers from the patient perspective and studies with mixed provider populations without distinct findings on nurses. After full-text screening, we excluded NP studies, to further narrow the research question. NPs work with patients in different contexts than RNs, and NP-specific findings merit their own review. We also opted to exclude studies of midwives since there are both nurse-midwives and midwives who have different educational paths and scopes of practice, thus concluding a separate study would be needed specific to that cadre.

2.2.2. Search strategy

Authors LG, LB and SM conducted a literature search using the PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Web of Science, and PsycINFO databases with combinations of the terms “nurs*”, “language barrier”, “limited English proficiency”, “interpreter”, “immigrant”, and “health literacy” for research studies published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese, reflecting the language capacities of the team members. We included studies published from 2010 through November 2019 to reflect recent global migration trends. To enhance search rigor and follow the Arksey and O’Malley comprehensive scoping review search guidelines [12], we searched reference lists and a journal special edition specific to communication concerns in healthcare. LG and LB conducted both title and abstract and full-text screening, applying the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by either SM or AS.

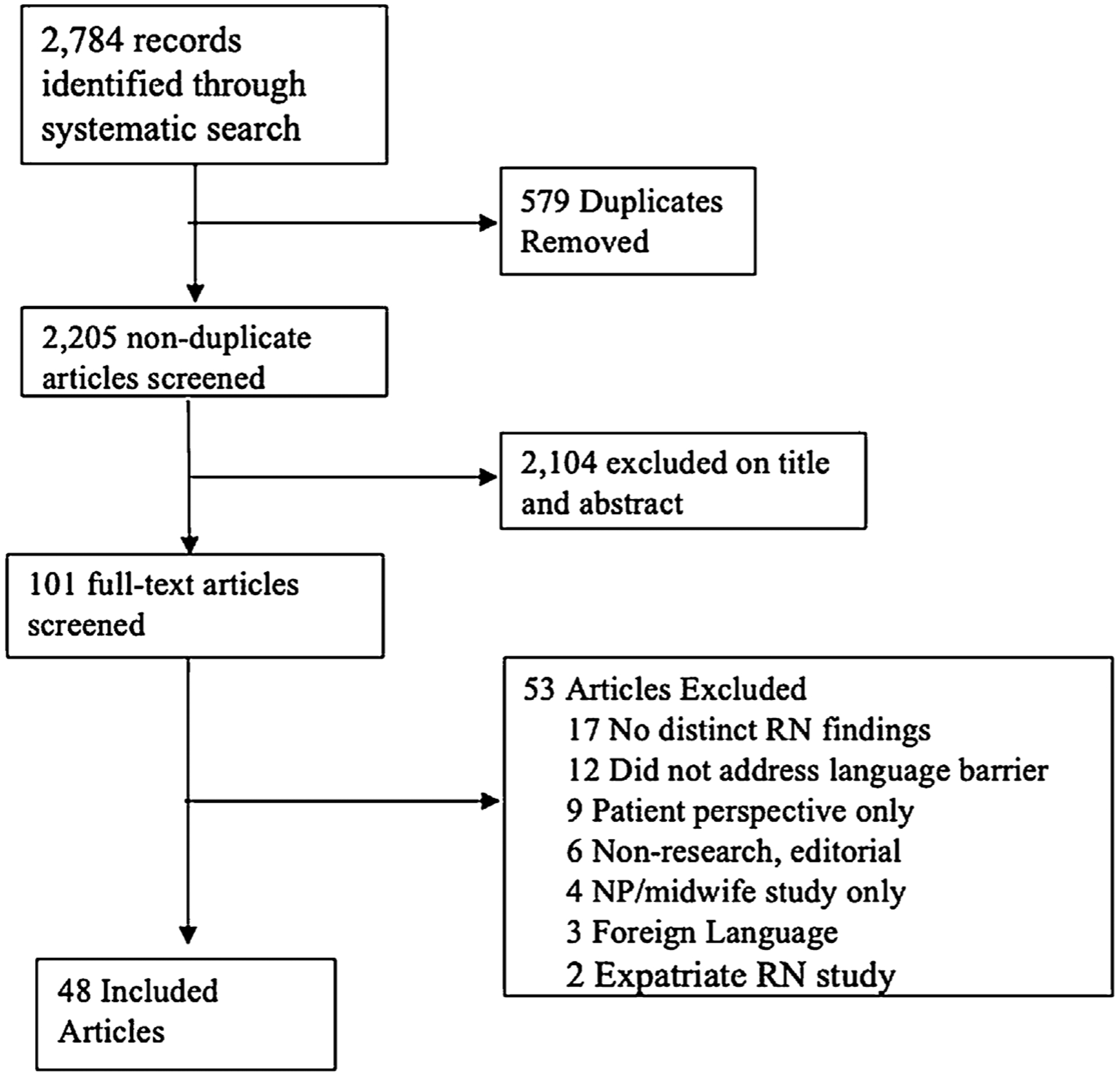

The original searched returned 2,784 titles, and selection was managed through Covidence. Duplicate articles (579) were removed leaving 2,205 remaining titles. Following title and abstract screening, 101 articles remained. Full-text data extraction eliminated an additional 53 publications, most of which did not report distinct RN findings (17) or did not address language barriers (12). The decision to exclude NP and midwife studies through the iterative process eliminated 4 full-text articles. Fig. 1 reports the search strategy and lists all reasons for full-text exclusion.

Fig. 1.

Search Screening Process.

2.3. Data analysis

Due to the volume of articles included in the review, the analytic process naturally involved conducting a general thematic analysis using an iterative coding approach. When documents are the “data” for a study, general thematic analysis is used to understand both content and context of the data sources [14]. LG and LB reviewed content of the selected articles then extracted and reduced data to identify key themes consistent with the review objectives, with AS providing a confirmatory review of the analysis.Themes were organized into a table to facilitate comparison and synthesis and conclusions were reached via consensus. All articles were initially analyzed together, with no distinction between country or practice setting. Findings unique to specific cadres of nurses or commonalities between settings were then extracted.

2.4. Critical appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative, cohort study, and case control study checklists were used to appraise quality depending on study design [15]. LG appraised all studies, and any disagreements were discussed between the authors. Study quality was not a factor in inclusion or exclusion criteria, as per the Arksey and O’Malley scoping review framework. The team, however, deemed it important to provide quality assessments of the included studies for the purpose of this review.

3. Results

Forty-eight articles formed the final sample for this review. The studies represent a total of 4,766 nurses working in 16 countries, 480 other providers, 19,787 patients or patient encounters, and reflect a broad range of methodologies and study populations. Table 1 summarizes study methods, population, setting, and geographic location. Table 2 lists study findings, and Table 3 summarizes strengths and weaknesses.

Table 1.

Design, Context, Population and Geographic Location by Study

| Author et al (Year) | Study Design | Context of Practice | Study Population | Geographic Location of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali & Johnson. (2017) | Qualitative Descriptive | Acute Care | 59 RNs | United Kingdom |

| Ali & Watson (2018) | Qualitative Descriptive | Acute Care/Tertiary Care | 59 RNs | United Kingdom |

| Alm-Pfrunder et al. (2018) | Qualitative | Prehospital Ambulance | 11 RNs | Sweden |

| Amoah et al. (2019) | Qualitative Exploratory | Acute Care | 6 RN, 7 patients | Ghana |

| Azize et al. (2018) | Quantitative Descriptive | Minor Injuries Unit | 20 RNs, 20 Nursing Students | United Kingdom |

| Badger et al. (2012) | Mixed Methods | Nursing Home | 101 RN Managers surveyed; 13 RN managers interviewed | United Kingdom |

| Balakrishnan et al. (2016) | Quantitative Prospective Cohort | Emergency | 12 RNs in 163 Patient encounters | United States |

| Barnes et al. (2011) | Mixed Methods | Home Care / Public Health Nursing | 17 RNs, 8 patients, 2 interpreters, 3 interpreter managers; 1304 RN-patient encounters | United Kingdom |

| Beckstrand et al. (2010) | Quantitative Descriptive | Pediatric ICU | 1047 RNs | United States |

| Bramberg & Sandman (2013) | Qualitative Descriptive | Home Care | 12 RNs, 11 Social Workers, 4 Nurse Assistants | Sweden |

| Chae & Park (2019) | Qualitative Exploratory Descriptive | Outpatient Clinic | 16 RNs | South Korea |

| Clayton et al. (2016) | Qualitative | Operating Room, Acute Care | 14 RNs | Australia |

| Coleman & Angosta (2017) | Qualitative Exploratory | Acute care | 40 RNs | United States |

| Diamond et al. (2012) | Quantitative Descriptive | Acute care | 65 RNs, 68 MDs | United States |

| Eklof et al. (2015) | Qualitative Descriptive | Public Health | 8 RNs | Finland |

| Fatahi et al. (2010) | Qualitative | Acute Care | 14 RNs | Sweden |

| Galinato et al. (2016) | Qualitative Descriptive | Acute Care- Medical Surgical | 7 RNs | United States |

| Granhagen Jungner et al. (2019) | Quantitative Descriptive | Pediatric Oncology | 151 RNs, 62 Nurse Assistant, 54 MD | Sweden |

| Hendson et al. (2015) | Qualitative Exploratory | NICU | 31 RN, 27 other providers (RT, NP, MD, students, administrative staff, SW) | Canada |

| Ian et al. (2016) | Qualitative Exploratory | Mixed | 17 RNs | United States |

| Jackson & Mixer (2017) | Qualitative Descriptive | Acute Care | 7 RN-patient dyads | United States |

| Kallakorpi et al. (2018) | Qualitative | Inpatient Psychiatric | 5 RNs, Encounters with 9 Patients | Finland |

| Kaur et al. (2019) | Quantitative Pre and Post Intervention | Oncology | 53 RNs | Australia |

| Machado (2013) | Mixed Methods | Acute Care | 11 RNs, 23 nursing technicians, 3 nursing assistants | Brazil |

| McCarthy et al. (2013) | Qualitative Descriptive | Mixed | 7 RNs | Ireland |

| Mottelson et al. (2018) | Quantitative Descriptive | Mixed Acute Care | 78 Charge RNs | Denmark |

| Patriksson et al. (2019) | Quantitative Descriptive | Neonatal | 484 RNs, 54 MDs, 320 nurse assistants | Sweden |

| Plaza Del Pino et al. (2013) | Qualitative Ethnography | Acute Care | 32 RNs | Spain |

| Rifai et al. (2018) | Inductive Qualitative | Public Health | 11 RNs | Sweden |

| Rosendahl et al. (2016) | Qualitative Exploratory Descriptive | Nursing Home | 9 Vocational Nurses, 5 Family Members | Sweden |

| Ross et al. (2016) | Quantitative Descriptive | Mixed Acute Care | 112 RNs, 48 Midwives, 64 Allied Health | Australia |

| Savio & George (2013) | Quantitative Descriptive | Acute Care | 100 RNs | India |

| Seale, Rivas, Al-Sarraj, et al. (2013) | Mixed Methods | Primary Care | 9 RNs, 36 Nurse-Patient Encounters | United Kingdom |

| Seale, Rivas, & Kelly (2013) | Qualitative Analysis of Nurse-Patient Interactions | Primary Care | 9 RNs, 36 Nurse-Patient Encounters | United Kingdom |

| Shuman et al. (2017) | Qualitative | Acute Care | 3 RNs, 3 nurse assistants | United States |

| Silvera-Tawil et al. (2018) | Mixed Methods | Acute Care | 15 RNs, 10 patients, 85 nurse-patient observations | Australia |

| Skoog et al. (2017) | Qualitative Inductive | Child Health Center | 13 RNs | Sweden |

| Squires et al. (2017) | Quantitative Descriptive | Home Health Care | RN and Physical Therapists assigned to 18,132 cases | United States |

| Squires et al. (2019) | Qualitative Exploratory Descriptive | Home Health Care | 35 RN, 3 PT, 1 OT | United States |

| Suurmond et al. (2017) | Qualitative | Pediatric Oncology | 13 RN, 12 MD | The Netherlands |

| Tay et al. (2012) | Qualitative | Oncology | 10 RNs | Singapore |

| Taylor & Alfred (2010) | Qualitative Case Study Approach | Mixed (Inpatient and Outpatient) | 23 RNs | United States |

| Tuot et al. (2012) | Quantitative Descriptive | Acute Care | 163 RNs, 116 MDs | United States |

| Valizadeh et al. (2017) | Qualitative | Pediatric Acute Care | 25 RNs, 9 patient parents | Iran |

| Watt et al. (2018) | Qualitative Inductive | Prison | 9 RNs, 30 patients | Australia |

| Watts et al. (2018) | Qualitative | Oncology | 21 RNs, 17 MD | Australia |

| Whitman et al. (2010) | Quantitative Descriptive | Schools | 1, 429 RNs | United States |

| Willey et al. (2018) | Qualitative Descriptive | Maternal Child Community Health | 26 RNs | Australia |

Table 2.

Descriptive Summary of Methods and Findings by Study

| Author et al (Date) | Purpose, Framework | Design, Data Collection and Analysis Methods | Major Findings | Key Statistics (Quantitative) and Key Themes (Qualitative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali & Johnson (2017) | “Explore bilingual nurses’ perspectives about provision of language concordant care to LEP patients and its impact on patients and nurses” (p . 424) |

|

|

|

| Ali & Watson (2018) | “Explore Nurses’ perspectives about language barriers they encounter when providing care to LEP patients from diverse linguistic background and nurses’ perspectives about impact of language barriers on provision of care to LEP patients” (p . e1154) |

|

|

|

| Alm-Pfrunder et al.(2018) | “Explore the strategies of nurses working in the ambulance service as regards assessing the needs of patients with limited Swedish-English proficiency” (p . 3700) |

|

|

|

| Amoah et al. (2019) | “Investigate Nurses’ and Patients’ experiences and views on the barriers to effective therapeutic communication to serve as a spring- board for further studies” (p . 2) |

|

|

|

| Azize et al. (2018) | “Identify the dimensions that influence how MIL) nurses and final-year preregistration children’s nursing students make decisions about the assessment of monolingual and English as an additional language (EAL) children following a minor injury and to understand the difficulties that nurses face whilst assessing pain” (p. 1082) |

|

|

|

| Badger et al. (2012) | “The aims of the study were to: describe the ethnicity of nursing home residents and staff and explore managers’ perceptions of readiness to meet the needs of diverse residents, including needs at the end of life” (p . 1727) |

|

|

|

| Balakrishnan et al. (2016) | “Examine the ability of triage nurses to assess language proficiency of patients as compared to patients’ self-reported proficiency … how language discordance impacts communication, door-to-room time, triage level, and patient satisfaction” (p . 370) |

|

|

|

| Barnes et al. (2011) | “To investigate whether the expected levels of delivery [of the FNP program] are attained and whether the nature of the crucial client-nurse relationship is affected [with an interpreter present]” (p .381) |

|

|

|

| Beckstrand et al. (2010) | “What are the sizes (intensities) and frequencies of obstacles and supportive behaviors in providing end-of-life care to infants and children as perceived by PICU nurses? What are the perceived obstacle magnitude (POM) scores? What are the perceived supportive behavior magnitude (PSBM) scores?” (p . 544) |

|

|

|

| Bramberg & Sandman (2013) | “Describe the experiences of home care providers and social workers in communication, via in-person interpreters, with patients who do not share a common language, and to offer suggestions for practice based on this description” (p . 161) |

|

|

|

| Chae & Park (2019) | “To explore the organizational level of cultural competence needed for foreign patient care from the perspective of Korean clinical RNs” (p . 198) |

|

|

|

| Clayton et al. (2016) | “Explore the lived experiences of perioperative nurses in a multicultural operating theatre in Melbourne, Australia” (p . 8) |

|

|

|

| Coleman, J., & Angosta, A. (2017) | “Examine the lived experiences of acute-care registered nurses when interacting with patients and their families with LEP” (p . 680) |

|

|

|

| Diamond et al. (2012) | “Describe how and when physicians and nurses with various levels of Spanish language proficiency use professional or ad-hoc interpreters or their own Spanish skills in common clinical scenarios in the acute care hospital setting” (p . 117–118) |

|

|

|

| Eklof et al. (2015) | “What factors have to be considered when using interpreters in primary health care in the care of immigrants?” (p . 144–145) |

|

|

|

| Fatahi et al. (2010) | “Explore nurse radiographers’ experiences of examining patients who do not speak Swedish” (p .775) |

|

|

|

| Galinato et al. (2016) | “To describe (a) the perceptions of nurses regarding their communication with patients with LEP, (b) how call lights affect their communication with patients with LEP, (c) the perceptions of nurses on the impact of advancement in call light technology on patients with LEP” (p .2) |

|

|

|

| Granhagen Jungner et al. (2019) | “Investigate communication over language barriers in pediatric oncology care …. How language barriers are overcome in different types of communication situations, how do different healthcare professions relate to such language barriers, to what extent are professional interpreters or other communicational tools used, and to what extent are other individuals used to translate?” (p . 1016) |

|

|

|

| Hendson et al. (2015) | “What are the experiences of health care providers in providing care to recently immigrated families (within five years of immigration) whose children were admitted to the NICU” (p . 18) |

|

|

|

| Ian et al. (2016) | “Explore registered nurses’ experiences with caring for non-English speaking patients and further how the experiences influence their clinical practice” (p . 258) |

|

|

|

| Jackson & Mixer (2017) | “Examine UTalk’s effectiveness for basic communication between Spanish speaking low English proficiency SSLEP families/guardians and nurses at the bedside on a pediatric medical-surgical unit” (p . 402) |

|

|

|

| Kallakorpi et al. (2018) | “To describe nurses’ experiences with caring for immigrant patients in psychiatric units” (p . 1803) |

|

|

|

| Kaur et al. (2019) | “Assess the feasibility of an online communication skills training intervention to increase cultural competence amongst oncology nurses working with individuals from minority backgrounds” (p . 1951) |

|

|

|

| Machado et al. (2013) | “Identify how the professionals in the nursing staff of a university hospital interact to take care of their deaf patients considering the knowledge of the Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) as a principle, which is indispensable for the planning of nursing care to this clientele” (p. 285) |

|

|

|

| McCarthy et al. (2013) | “Describe nurses’ experiences of language barriers and the use of interpreters within the context of an evolving healthcare environment in Ireland” (p . 336) |

|

|

|

| Mottelson et al. (2018) | “Investigate the attitudes and experiences of the university hospital’s charge nurses regarding the use of video interpretation” (p . 245) |

|

|

|

| Patriksson et al. (2019) | “To examine health care professionals’ use of interpreters and awareness of local guidelines for interpreted communication in neonatal care” (p . 3) |

|

|

|

| Plaza Del Pino et al. (2013) | “Determine how nurses perceive their communication with their Moroccan patients and identifying relevant barriers that exist for provision of culturally competent care” (p . 2–3) |

|

|

|

| Rifai et al. (2018) | “Describe the public health nurses’ experiences of using interpreters when meeting with Arabic- speaking first-time mothers” (p . 575) |

|

|

|

| Rosendahl et al. (2016) | “Understand and systematically describe personal experiences of the care provided to immigrants with dementia and the experiences of their family members and nursing staff “(p . 3) |

|

|

|

| Ross et al. (2016) | “Determine the frequency with which nursing, midwifery and allied healthcare staff encounter refugee patients in two public hospitals, how confident they are working with refugees, the effect on their work and any differences between the rural and urban settings” (p . 680) |

|

|

|

| Savio & George (2013) | “Find out difficulties that staff nurses experience in communicating with patients from culturally and linguistically different background and the staff nurses’ attitude towards the importance of communication in caring for those patients” (p . 142) |

|

|

|

| Seale, Rivas, Al-Sarraj et al. (2013) | “A comparison of fluent English consultations with ones that involve interpreters … explore the moral work done by participants” (p . 142) |

|

|

|

| Seale, Rivas, & Kelly (2013) | “Compare interpreted with fluent same-language consultations” (p . e126) |

|

|

|

| Shuman et al. (2017) | “Describe RNs’ and NAs’ perceptions of LEP patients’ call light use and their current communication practices with LEP patients” (p . 590) |

|

|

|

| Silvera-Tawil et al. (2018) | “To identify the following: (a) current practice regarding communication during standard care interactions between nursing staff and NESB (non English speaking background) patients, and the context of these interactions; (b) specific communication needs of nursing staff and patients during basic standard care interactions; (c) target words and/or phrases used during basic standard care interactions between nursing staff and NESB patients when an interpreter is not present; and (d) potential needs, challenges, technical requirements and uses of a mobile app for nursing staff (p . 4170) |

|

|

|

| Skoog et al. (2017) | “To elucidate CHS nurses’ experiences of identifying signs of PPD in non-Swedish-speaking immigrant mothers” (p . 740) |

|

|

|

| Squires et al. (2017) | “Explore a potential vulnerability in home health care service delivery by examining the frequency of language-concordant visit patterns among home health patients as captured in electronic health record and organizational administrative datasets” (p . 161) |

|

|

|

| Squires et al. (2019) | “Examine how providers saw their workloads affected by patient assignments involving limited English proficiency patients” (p . 3) |

|

|

|

| Suurmond et al. (2017) | “To explore those obstacles in pediatric cancer care that lead to barriers in the care process for ethnic minority patients” (p . 2) |

|

|

|

| Tay et al. (2012) | “To identify the factors that promote, inhibit or both promote and inhibit effective communication between inpatient oncology adults and Singaporean registered nurses” (p . 2648) |

|

|

|

| Taylor, R. & Alfred, M. (2010) | “To explore nurses’ perceptions of ways in which the health care organization can support them in the delivery of culturally competent care” (p . 595) |

|

|

|

| Tuot et al. (2012) | “We placed a dual-handset phone with 24- hour access to professional telephonic interpretation at the bedside of all patients admitted to the general medicine floor of the hospital and assessed change in nurse and physician use of professional interpreters” (p . 82) |

|

|

|

| Valizadeh et al. (2017) | “Identify the factors that influence nurse-to-parent communication in the provision of pediatric culturally sensitive care in Iran” (p . 476) |

|

|

|

| Watt et al. (2018) | “Explore the complexities of communication and interpreter use for CALD women prisoners accessing prison health care, with a view to improving service access for CALD women in prison” (p . 1160) |

|

|

|

| Watts et al. (2018) | “Explore organizational and systemic challenges encountered by HPs who work with minority cancer patients and caregivers” (p . 2) |

|

|

|

| Whitman et al. (2010) | “Describe the perceptions of school nurses of the increase in the ESL student population and the challenges they face in communicating with this population” (p . 209) |

|

|

|

| Willey et al. (2018) | “Explore service provision for Victorian regional refugee families from the perspective of MCH nurses and identify whether there are continuing professional development needs and MCH nurses who work with families from a refugee background” (p . 3389) |

|

|

|

Table 3.

Summary of Study Strengths and Weaknesses

| Author et al (Date) |

Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Ali & Johnson (2017) |

|

|

| Ali & Watson (2018) |

|

|

| Alm-Pfrunder et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Amoah et al. (2019) |

|

|

| Azize et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Badger et al. (2012) |

|

|

| Balakrishnan et al. (2016) |

|

|

| Barnes et al. (2011) |

|

|

| Beckstrand et al. (2010) |

|

|

| Bramberg & Sandman (2013) |

|

|

| Chae & Park (2019) |

|

|

| Clayton (2016) |

|

|

| Coleman & Angosta, (2017) |

|

|

| Diamond et al. (2012) |

|

|

| Eklof et al. (2015) |

|

|

| Fatahi (2010) |

|

|

| Galinato et al. (2016) |

|

|

| Granhagen Jungner et al. (2019) |

|

|

| Hendson et al. (2015) |

|

|

| Ian et al. (2017) |

|

|

| Jackson & Mixer (2017) |

|

|

| Kallakorpi et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Kaur et al. (2019) |

|

|

| Machado et al. (2013) |

|

|

| McCarthy et al. (2013) |

|

|

| Mottelson et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Patriksson et al. (2019) |

|

|

| Plaza Del Pino (2013) |

|

|

| Rifai et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Rosendahl et al. (2016) |

|

|

| Ross et al. (2016) |

|

|

| Savio & George (2013) |

|

|

| Seale, Rivas, Al-Sarraj et al. (2013) |

|

|

| Seale, Rivas, & Kelly (2013) |

|

|

| Shuman et al. (2017) |

|

|

| Silvera-Tawil et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Skoog et al. (2017) |

|

|

| Squires et al. (2017) |

|

|

| Squires et al. (2019) |

|

|

| Suurmond et al. (2017) |

|

|

| Tay et al. (2012) |

|

|

| Taylor & Alfred. (2010) |

|

|

| Tuot et al. (2012) |

|

|

| Valizadeh et al. (2017) |

|

|

| Watt et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Watts et al. (2018) |

|

|

| Whitman et al. (2010) |

|

|

| Willey et al. (2018) |

|

|

The majority of studies (32/48) addressed language barriers directly in the research question, with the remaining studies investigating issues of culture or communication. RNs were analyzed alone in 26 studies. Twelve studies used mixed provider populations and 11 studies included patients, either observed or analyzed as a dyad with a provider or as a participant. Thirty of the studies were qualitative investigations 5 studies used mixed-methods, and the remaining 13 were quantitative studies with various designs.

The articles represented diverse inpatient and outpatient healthcare settings including emergency department, prison, school, inpatient psychiatric, nursing home and community health. Twenty-five studies analyzed encounters in the hospital setting. Geographically, sixteen countries were represented, with the majority of studies from the United States (13) and Scandinavia (11).

The analysis produced four themes: (1) Interpreter Use/Misuse, (2) Barriers to and Facilitators of Quality Care, (3) Cultural Competence, and (4) Interventions. The synthesis reflects the common complexities that nurses face globally due to language barriers and identifies nursing interventions aimed to improve outcomes.

3.1. Interpreter use/misuse

Nurse interaction with interpreters was a common theme throughout the literature. While experiences with interpreters varied, findings were similar across studies.

3.1.1. Accessibility and usability

The accessibility and usability of professional interpreters impacted care. The articles studied multiple methods of interpretation, including in-person, telephone, and video. Nurses consistently expressed difficulty in accessing interpreters [16–26] and usability issues with telephone translation [17,20,27]. Some nurses opted to use apps or websites when interpreters were unavailable [24,28], while others chose not to use an available professional interpreter [26,29–31]. When working with interpreters, nurses spoke to them, rather than patients, and those conversations were less personal than language concordant encounters [32]. Nurses also expressed concerns about interpreter translation accuracy [16,20,25,33–36].

Despite these difficulties, nurses described improved care when working in settings with adequate professional interpreter staffing [21,28,35–37]. Clinically, discharge planning [30], objective translation [25], and patient involvement in decision-making [28] improved when nurses accessed a professional interpreter. Interpreters also served as a cultural bridge [33–35] between nurses and their patients. Nurses generally preferred professional, in-person interpretation if available, but often relied on other communication methods.

3.1.2. Ad hoc interpreters

Ad hoc interpreters are uncertified translators, such as family or non-interpreter staff. Perceived insufficient interpreter access forced nurses to use ad hoc interpreters, including staff [16,23,28,30,36,38,39], family or friends [18–20,23,25,28,30,38–43], or in the case of school and prison nurses, bilingual peers[26,31]. Ad hoc interpreters led to quality issues around confidentiality [16,26], censoring of sensitive information [23,25], concerns about translation accuracy [16,20,25,33,34,36,44] and reliance on inadequate language skills [30]. For bilingual nurses specifically, the literature consistently highlighted concerns about workload and stress when assuming a dual nurse-interpreter role [23,27,36,45].

3.2. Barriers to and facilitators of quality care

The literature identified both barriers and facilitators either specific to the RN role or related to systems and policies that impacted the quality of care delivered by nurses to non-language concordant patients. Despite differences in care settings and geography, findings were similar across the literature.

3.2.1. Barriers

Nurses in various practice contexts both encountered and created barriers to high quality patient care. Descriptions of modified nursing care to patients with language barriers were common. For example, nurses feared non-language-concordant patients misunderstood call light importance [24] and described less frequent call light usage by non-language concordant patients [38]. Similarly, non-language-concordant patients spent less time with nurses [25], struggled to provide a detailed history [25,46] and had frequent uninterpreted encounters with nurses [17,30]. Nurses described poor communication with non-language concordant patients as potentially riskier than no communication with these patients at all [46]. Two studies further described how language barriers complicated end of life care [47,48].

Language barriers also impacted the nurse-patient relationship in ways participants perceived as negative and it was magnified in certain settings, including psychiatric ones [49], NICU [50], prehospital and ambulances [17], prisons [26], and maternal child community health [33,51]. Interpreters censored some patient information, such as poor treatment adherence, when translating nurse-patient encounters according to some nurses [52]. Nurses further worried that patients did not understand health-specific education [21,33,46,50,53]. These modifications to routine care impacted both patient relationships and care delivery, which ultimately may affect safety.

Workforce related barriers were identified in the literature in multiple contexts. Routine care of non-language-concordant patients, even with an interpreter, required extra time [20–23,27,34,37,38,45,50,53,54]. Nurses described a lack of leadership support around staffing, policies, and increased workload [18,20,36,45,50]. Similarly, nurses felt undertrained and unprepared to manage language barriers effectively [20,36,42,47]. Finally, gender limitations on visitation for pediatric patients forced nurses to communicate with non-language concordant mothers, despite language-concordance with the fathers [18].

3.2.2. Facilitators

The literature also identified nursing specific strategies, bedside tools, and workplace structure that helped nurses improve care delivery to non-language-concordant patients. Nurses found their years of work experience as beneficial to work around language barriers [45,55] or to work as both an interpreter and RN [30]. Bedside strategies included nonverbal communication [17–19,23,25,38,39,46,56,57] or using structured assessments [17,30]. All these actions added to nurse workload, regardless of setting.

Workforce variables also facilitated higher quality nursing care in multiple care contexts. Collaborative, consistent relationships with interpreters helped nurses improve relationships with non-language-concordant patients [28,35,48]. Nurses also described using time and effort to connect to and understand non-language-concordant patients to address nursing-specific needs like pain [21]. Similarly, nurses described personal growth and care-delivery improvements as a result of working with patients through a language barrier [37]. While some nurses described these behaviors as instinctual, others desired education from management regarding how to better serve these patients [18,50].

3.3. Cultural competence

Language and culture are linked, and nurses’ self-assessed skills in these areas affected how they perceived their care delivery. A nurse’s own culture, similar or not to a patient’s, impacted care delivery [18–20,23,36,39,42,48,50,53,58]. Nurses observed cultural beliefs impacting healthcare decisions or treatments [19,23,39,47,48] and described their own knowledge deficits that inhibited connection with patients and comprehension of their needs [36,42,50,59]. Some nurses expressed xenophobia [36,42], while others desired cultural sensitivity training [36,39,60]. The implicit and explicit ties between language and culture were apparent to the nurses, but their comfort with integrating them into care delivery appeared to vary as did their reasons for what shaped their comfort levels.

3.4. Interventions

Five of the studies involved the design or testing of interventions regarding nursing care of non-language-concordant patients. Four studies enhanced bedside communication through tools and technology [40,44,46,61]. Of these, two studies tested care improvements [40,61], while the others addressed tool design, feasibility, or acceptability. One study tested the impact an online cultural humility tool could have on nursing practice, finding significant self-assessed improvements in practice in post-testing [62]. Two studies facilitated a discussion around proposed tools to improve communication for non-language-concordant patients [24,46]. RNs in these studies found the use of symbols and pictures as innovative [24] and identified nursing-specific encounters where a bedside communication tool would be beneficial including responding to call lights, consenting for procedures, assessing neurologic status, and providing standard daily care such as toileting [46]. While the majority of the literature around nurses and language barriers was exploratory, these studies described interventions to address some of the barriers nurses identified in the qualitative data.

3.5. Critical appraisal

We reviewed the studies’ strengths and weaknesses identified through the CASP checklists. Common methodological concerns for qualitative papers centered around data analysis, with many studies providing little description of the analysis process [22,25,26,37,38,42,44,46,53] or researchers failing to reflect on their own experiences as a source of potential bias throughout the analysis process [16,20,23,25,26,32–35,37,45,49,52,53,56]. Nonetheless, some qualitative studies applied methods to add rigor, including triangulation, member checking, written audit trails and detailed coding descriptions [16–19,21,23,24,26,27,32,35,44, 45,48–50,52,56,60,63]. Three articles, two from a single study, confirmed intercoder reliability using either Cohen’s kappa or Holsti’s method [18,32,52], an approach not always necessary in qualitative research and the subject of methodological debates.

The majority of quantitative studies were descriptive studies. The most common methodological concerns for these studies were samples that were predominantly or 100% female [21,47,58,62] or had survey response rates below 50% [41,47,55]. The latter is less concerning given methodological advances indicating that low response rates can still produce generalizable results [64]. Lastly, one study comparing providers’ use of Spanish language by skill level used self-assessed proficiency rather than verified testing [30]. Nonetheless, studies applied methods to improve study quality. Survey studies used pretesting, focus groups, detailed survey-development methodologies and pre-existing valid and reliable tools to enhance study rigor [28,29,40,47,55,58]. One study utilized random sampling [47], with the rest using convenience or purposive methods. Surprisingly, only two studies determined sample size with power analysis [29,62].

Importantly, the articles in the review did not equitably represent the breadth of settings where nurses practice. The majority of articles investigated hospital-based nurses. The lack of research about nurses practicing in non-hospital sites is concerning since language barriers can exist anywhere a nurse works and language resources available in nonhospital settings may differ in feasibility and accessibility. Similarly, the unique interactions and relationships between nurses and patients were not adequately addressed in mixed provider studies that did not separate findings by role.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This review captures the recent evidence associated with nursing care in the presence of a language barrier. The body of literature highlights the linguistic complexities that nurses face from a global perspective and describes how culture, the role of the interpreter, and nursing strategies and tools impact care delivery, quality, and outcomes. A patient’s language preference that differs from a country’s official language is a key social risk factor and determinant of health. This study highlighted how nurses work with and around language barriers with patients and captured some of the complexity of those interactions. Findings across countries were similar, despite differences in migration trends or language- nurses facing language barriers desire to provide quality care but encounter many obstacles, regardless of setting, language, or country.

4.1.1. Interpreters

The presence of a professional interpreter has proven to mitigate health disparities through decreased errors and greater access and satisfaction [65]. Nurses in the included literature, however, struggled to access interpreters and expressed distrust in their skills. At the same time, policies around the provision of healthcare language services including training, certification and required use of interpreters, differ greatly between nations [66]. Even in countries with laws which ensure language-concordant healthcare, nurses in this review expressed concerns. Ad hoc interpreters are not an appropriate substitute in most circumstances due to concerns around confidentiality, translation error, and workload for bilingual staff. A lack of regulation of the interpreting industry more broadly may contribute the nurses’ concerns.

4.1.2. Workforce and workplace

Nurses expressed concern around role-specific patient interactions such as call-light usage, pain assessment, or patient education that differ when working through a language barrier. While nurses employed strategies to overcome those issues, concerns about patient safety and RN workload were described across the literature. Nurses asked for greater logistical support and role-specific education from management around cultural sensitivity and interpreter use in order to address the health disparity created by a language barrier. Despite similar findings across the literature around both the barriers to and facilitators of high quality nursing care, no standardized model of care delivery existed, even amongst nurses practicing in the same site or analyzed in the same study.

4.1.3. Limitations

Like all reviews, the limitations center on the quality of the search as well as how the authors mitigated their own biases. We adhered to Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological recommendations [12] to enhance rigor in the data evaluation, comparison, and reduction stages. The team conducting the study, however, were all registered nurses from the USA with varying levels of experience and three members of the team are bilingual RNs. One team member, however, did have extensive international nursing workforce research experience across 34 countries. While this helped the interpretation of our findings, the conclusions may reflect our biases that favor language concordant patient-provider encounters.

4.2. Conclusion

Even though the results of this review highlight the complexity and challenges nurses face due to language barriers, the more surprising result was how few studies involved nurses as the primary study population. A brief physician focused search in PubMed produced over 150 research studies, largely in primary care, as a comparison. While the findings from these physician-focused studies are generally similar to those of this review [67–69], nurses spend more time with patients than physicians [70] and have different roles in all settings. These differences merit individualized, RN-specific investigations regarding language barriers as well as interventions aside from interpreters that can enhance nurse-patient communication. In addition to testing interventions, additional qualitative data is needed from more geographic regions to ensure that the trends identified in this scoping review are applicable worldwide.

Patient-provider language barriers are global issues that affect all providers. Our study captured the lack of research focused on nurses and we suspect there is a dearth of research about other allied healthcare roles as well. The reduction of the risk for health disparities related to language barriers has to involve understanding the best methods for each role in order to bridge them. This study summarized and noted the commonalities and differences of nurse experiences when facing language barriers. More research and its translation into the workplace will enhance the precision of their practice with this population and contribute to disparities reduction.

4.3. Practice implications

The findings across care settings and countries have identified various implications for practice which apply to a global nursing population. Healthcare leadership and nursing management have an opportunity to create structural and staffing changes to reflect the demands nurses face when working with language barriers. Bilingual nurses with certified skills and nurses dually trained as interpreters are two options. For bilingual staff, leadership must ensure that their self-assessed language skills are adequate to meet patient needs. It is notable that no study addressed testing or certification of providers who chose to use their own language skills rather than an interpreter. This was true even for studies published in the US after the implementation of Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act which required healthcare facilities to test provider language proficiency [71].

Proficiency testing in entry-level educational programs would certify language skills early in health professionals’ careers and potentially foster the appropriate use of interpreters long term. Entry-level testing via a nationally standardized program would also save costs for healthcare systems who bear the burden of language assessment. Development, testing, implementation, and evaluation of nursing specific protocols and policies around staffing and time management could help nurses address common concerns regarding the added workload that comes with working with patients with language barriers. Standardizing appropriate utilization of bilingual nurses in the workplace is critical so that serving as a dual-role interpreter does not supersede their nursing role.

Based on the findings, we have identified several opportunities for future research. First, research needs to confirm when the critical interactions during care delivery should require an interpreter and distinguish from those that do not. Second, we need to understand what is considered “acceptable” for basic communication since an interpreter cannot be present for RNs at all times. In addition, the qualitative findings in this review identified numerous areas which could be tested through quantitative interventions using nurse-patient dyads.

Similarly, continued investigation into the experiences of nurses working outside of the hospital setting is needed to fully understand the impact of cultural and language incongruencies, since their resources and patient relationships are distinct. The lack of research on mental health nurses is particularly significant. A 2016 systematic review showed that immigrants already use mental health services less than their native counterparts [72] and poor language services may be one explanation. More research examining mental health services delivery in the context of language barriers is needed. As global demographics continue to change, continued research on the role-specific impact of language barriers in health care and its translation into nursing practice is needed to both address the growing health disparity and to adhere to and inform policy.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, United States [R01HS023593].

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

- 2019 Consultant, Qualitative Methods, National Council of State Boards of Nursing, USA.

- 2016–18 Consultant, International Nurse Migration, Kings College London, London, UK.

- 2018 Consultant with travel grant, Survey Instrument Translation, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic.

- 2018 Conference speaker honoraria, Yonsei University School of Nursing, Seoul, South Korea. −2015 to present, Principal, ABC Education Consultants LLC, New York, USA.

References

- [1].Betancourt JR, Renfrew MR, Green AR, Lopez L, Wasserman M, Improving Patient Safety Systems for Patients with Limited English Proficiency: A Guide for Hospitals Washington D.C, (2012).

- [2].United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2018, (2019).

- [3].Chen Jacobs, Karliner Agger-Gupta, Mutha, The need for more research on language barriers in health care: A proposed research agenda, Milbank Q. 84 (2006) 111–133, doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pippins JR, Alegria M, Haas JS, Association between language proficiency and the quality of primary care among a national sample of insured Latinos, Med. Care 45 (2007) 1020–1025, doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814847be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mangione-Sith Arthur, Meischke Zhou, Strelitz A, Garcia Brown, Impact of English proficiency on care experiences in a pediatric emergency departmen, Acad. Pediatr 15 (2015) 218–224, doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wilson CC, Patient safety and healthcare quality: The case for language access, Int. J. Heal. Policy Manag 1 (2013) 251–253, doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].VanderWielen LM, Enurah AS, Rho HY, Nagarkatti-Gude DR, MichelsenKing P, Crossman SH, Vanderbilt AA, Medical interpreters: Improvements to address access, equity, and quality of care for limited-English-pro cient patients, Acad. Med 89 (2014) 1324–1327, doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schwei RJ, Del Pozo S, Agger-Gupta N, Alvarado-Little W, Bagchi A, Chen AH, Diamond L, Gany F, Wong D, Jacobs E. a., Changes in research on language barriers in health care since 2003: A cross-sectional review study, Int. J. Nurs. Stud 54 (2016) 36–44, doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lindholm M, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G, Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates, J. Gen. Intern. Med 27 (2012) 1294–1299, doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2041-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Squires A, Strategies for overcoming language barriers in healthcare, Nurs. Manage 49 (2018) 20–27, doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000531166.24481.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien K, Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology, Implement. Sci 5 (2010) 1–18, doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511814563.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Arksey H, O’Malley L, Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework, Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol 8 (2005) 19–32, doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Davis K, Drey N, Gould D, What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature, Int. J. Nurs. Stud 46 (2009) 1386–1400, doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miller FA, Alvarado K, Incorporating documents into qualitative nursing research, J. Nurs. Scholarsh 37 (2005) 348–353, doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Programme C.A.S., CASP Checklists, (2018).

- [16].Ali PA, Watson R, Language barriers and their impact on provision of care to patients with limited English proficiency: Nurses’ perspectives, J. Clin. Nurs 27 (2018) e1152–e1160, doi: 10.1111/jocn.14204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Alm-Pfrunder AB, Falk AC, Vicente V, Lindström V, Prehospital emergency care nurses’ strategies while caring for patients with limited Swedish–English proficiency, J. Clin. Nurs 27 (2018) 3699–3705, doi: 10.1111/jocn.14484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Ghahramanian A, Aghajari P, Foronda C, Factors influencing nurse-to-parent communication in culturally sensitive pediatric care: a qualitative study, Contemp. Nurs 53 (2017) 474–488, doi: 10.1080/10376178.2017.1409644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Amoah VMKA, Anokye R, Boakye DS, Acheampong E, Budu-ainooson A, Okyere E, Kumi-boateng G, Yeboah C, Afriyie JO, A qualitative assessment of perceived barriers to effective therapeutic communication among nurses and patients, BMC Nurs. 18 (2019) 1–8, doi: 10.1186/s12912-019-0328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chae D, Park Y, Organisational cultural competence needed to care for foreign patients: A focus on nursing management, J. Nurs. Manag 27 (2019) 197–206, doi: 10.1111/jonm.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Coleman J, Angosta A, The lived experiences of acute-care bedside registered nurses caring for patients and their families with limited English proficiency: A silent shift, J. Clin. Nurs 26 (2017) 678–689, doi: 10.1111/jocn.13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Eklof N, Hupli M, Leino-Kilpi H, Nurses’ perceptions of working with immigrant patients and interpreters in Finland, Public Health Nurs. 32 (2015) 143–150, doi: 10.1111/phn.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fatahi N, Mattsson B, Lundgren SM, Hellström M, Nurse radiographers’ experiences of communication with patients who do not speak the native language, J. Adv. Nurs 66 (2010) 774–783, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Galinato Montie, Shuman Patak, Titler, Perspectives of nurses on patients with limited English proficiency and their call light sse, Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res 3 (2016) 1–9, doi: 10.1177/2333393616637764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McCarthy J, Cassidy I, Graham MM, Tuohy D, Conversations through barriers of language and interpretation, Br. J. Nurs 22 (2014) 335–339, doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.6.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Watt K, Hu W, Magin P, Abbott P, “Imagine if I’m not here, what they’re going to do?”—Health-care access and culturally and linguistically diverse women in prison, Health Expect. 21 (2018) 1159–1170, doi: 10.1111/hex.12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Squires Miner, Liang Lor, Ma W, Stimpfel, How language barriers influence provider workload for home health care professionals: A secondary analysis of interview data, Int. J. Nurs. Stud 99 (2019) 103394, doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Granhagen Jungner J, Tiselius E, Blomgren K, Lützén K, Pergert P, Language barriers and the use of professional interpreters: A national multisite cross-sectional survey in pediatric oncology care, Acta Oncol. (Madr) 58 (2019) 1015–1020, doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1594362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Azize PM, Cattani A, Endacott R, Perceived language proficiency and pain assessment by registered and student nurses in native English-speaking and EAL children aged 4–7 years, J. Clin. Nurs 27 (2018) 1081–1093, doi: 10.1111/jocn.14134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Diamond LC, Tuot DS, Karliner LS, The use of Spanish language skills by physicians and nurses: Policy implications for teaching and testing, J. Gen. Intern. Med 27 (2012) 117–123, doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1779-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Whitman MV, Davis J. a., Terry AJ, Perceptions of school nurses on the challenges of service provision to ESL students, J. Community Health 35 (2010) 208–213, doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Seale Rivas, Kelly, The challenge of communication in interpreted consultations in diabetes care, Br. J. Gen. Pract 63 (2013) e125–e133, doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X668069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Barnes J, Ball M, Niven L, Providing the Family-Nurse Partnership programme through interpreters in England, Health Soc. Care Community 19 (2011) 382–391, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bramberg EB, Sandman L, Communication through in-person interpreters: A qualitative study of home care providers’ and social workers’ views, J. Clin. Nurs 22 (2013) 159–167, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rifai E, Janlöv A, Garmy P, Public health nurses’ experiences of using interpreters when meeting with Arabic-speaking first-time mothers, Public Health Nurs. 35 (2018) 574–580, doi: 10.1111/phn.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Taylor RA, Alfred MV, Nurses’ perceptions of the organizational supports needed for the delivery of culturally competent care, West. J. Nurs. Res 32 (2010) 591–609, doi: 10.1177/0193945909354999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ian C, Nakamura-Florez E, Lee YM, Registered nurses’ experiences with caring for non-English speaking patients, Appl. Nurs. Res 30 (2016) 257–260, doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Shuman C, Montie M, Galinato J, Patak L, Titler M, Registered nurse and nursing assistant perceptions of limited English-proficient patient-clinician communication, J. Nurs. Adm 47 (2017) 589–591, doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Badger F, Clarke L, Pumphrey R, Clifford C, A survey of issues of ethnicity and culture in nursing homes in an English region: Nurse managers’ perspectives, J. Clin. Nurs 21 (2012) 1726–1735, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mottelson IN, Sodemann M, Nielsen DS, Attitudes to and implementation of video interpretation in a Danish hospital: A cross-sectional study, Scand. J. Public Health 46 (2018) 244–251, doi: 10.1177/1403494817706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Patriksson K, Wigert H, Berg M, Nilsson S, Health care professional’s communication through an interpreter where language barriers exist in neonatal care: A national study, BMC Health Serv. Res 19 (2019) 1–8, doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4428-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Plaza Del Pino FJ, Soriano E, Higginbottom GM, Sociocultural and linguistic boundaries influencing intercultural communicaetion between nurses and Moroccan patients in southern Spain: A focused ethnography, BMC Nurs. 12 (2013) 14, doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Balakrishnan V, Roper J, Cossey K, Roman C, Jeanmonod R, Misidenti cation of English language pro ciency in triage: Impact on satisfaction and door-to-room time, J. Immigr. Minor. Health 18 (2016) 369–373, doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jackson KH, Mixer SJ, Using an iPad for basic communication between Spanish-speaking families and nurses in pediatric acute care: A feasibility pilot study, Comput. Inform. Nurs 35 (2017) 401–407, doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ali PA, Johnson S, Speaking my patient’s language: Bilingual nurses’ perspective about provision of language concordant care to patients with limited English proficiency, J. Adv. Nurs 73 (2017) 421–432, doi: 10.1111/jan.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Silvera-Tawil D, Pocock C, Bradford D, Donnell A, Harrap K, Freyne J, Brinkmann S, CALD Assist-Nursing: Improving communication in the absence of interpreters, J. Clin. Nurs 27 (2018) 4168–4178, doi: 10.1111/jocn.14604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Beckstrand RL, Rawle NL, Callister L, Mandleco BL, Pediatric nurses’ perceptions of obstacles and supportive behaviors in end-of-life care, Am. J. Crit. Care 19 (2010) 543–552, doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tay LH, Ang E, Hegney D, Nurses’ perceptions of the barriers in effective communication with inpatient cancer adults in Singapore, J. Clin. Nurs 21 (2012) 2647–2658, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kallakorpi S, Haatainen K, Kankkunen P, Nurses’ experiences caring for immigrant patients in psychiatric units, Int. J. Caring Sci 11 (2018) 1802–1811. https://proxy.hsl.ucdenver.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=134112537&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hendson L, Reis MD, Nicholas DB, Health care providers’ perspectives of providing culturally competent care in the NICU, J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 44 (2015) 17–27, doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Skoog M, Hallström I, Berggren V, “There’s something in their eyes” - Child Health Services nurses’ experiences of identifying signs of postpartum depression in non-Swedish-speaking immigrant mothers, Scand. J. Caring Sci 31 (2017) 739–747, doi: 10.1111/scs.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Seale C, Rivas C, Al-Sarraj H, Webb S, Kelly M, Moral mediation in interpreted health care consultations, Soc. Sci. Med 98 (2013) 141–148, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Clayton J, Isaacs AN, Ellender I, Perioperative nurses’ experiences of communication in a multicultural operating theatre: A qualitative study, Int. J. Nurs. Stud 54 (2016) 7–15, doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Squires A, Peng TR, Barrón-vaya Y, Feldman P, An exploratory analysis of home health care visit patterns, Home Health Care Manag. Pract 29 (2017) 161–167, doi: 10.1177/1084822317696706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ross L, Harding C, Seal A, Duncan G, Improving the management and care of refugees in Australian hospitals: A descriptive study, Aust. Health Rev 40 (2016) 679–685, doi: 10.1071/AH15209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rosendahl SP, Söderman M, Mazaheri M, Immigrants with dementia in Swedish residential care: An exploratory study of the experiences of their family members and nursing staff, BMC Geriatr. 16 (2016) 1–12, doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0200-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Machado W, Machado D, Figueiredo N, Tonini T, Miranda R, Oliveira G, Sign Language, How the Nursing Staff Interacts To Take Care of Deaf Patients? Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. é Fundam 5 (2013) 283–292, doi: 10.9789/2175-5361.2013v5n3p283 Online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Savio N, George A, The perceived communication barriers and attitude on communication among staff nurses in caring for patients from culturally and linguistically diverse background, Int. J. Nurs. Educ 5 (2013) 141–146, doi: 10.5958/j.0974-9357.5.1.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Suurmond J, Lieveld A, Wetering M, Schouten-van Meeteren AYN, Towards culturally competent paediatric oncology care. A qualitative study from the perspective of care providers, Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl) 26 (2017), doi: 10.1111/ecc.12680 n/a-N.PAG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Willey SM, Cant RP, Williams A, McIntyre M, Maternal and child health nurses work with refugee families: Perspectives from regional Victoria, Australia, J. Clin. Nurs. (John Wiley Sons, Inc.) 27 (2018) 3387–3396, doi: 10.1111/jocn.14277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Tuot DS, Lopez M, Miller C, Karliner LS, Impact of an easy-access telephonic interpreter program in the acute care setting: An Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention, Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf 38 (2012) 81–88. https://proxy.hsl.ucdenver.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=108152923&site=ehost-live. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kaur R, Meiser B, Zilliacus E, Tim Wong WK, Woodland L, Watts K, Tomkins S, Kissane D, Girgis A, Butow P, Hale S, Perry A, Aranda SK, Shaw T, Tebble H, Norris C, Goldstein D, Evaluation of an online communication skills training programme for oncology nurses working with patients from minority backgrounds, Support Care Cancer 27 (2019) 1951–1960, doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Watts KJ, Meiser B, Zilliacus E, Kaur R, Taouk M, Girgis A, Butow P, Kissane DW, Hale S, Perry A, Aranda SK, Goldstein D, Perspectives of oncology nurses and oncologists regarding barriers to working with patients from a minority background: Systemic issues and working with interpreters, Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 27 (2018) 1, doi: 10.1111/ecc.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Massey DS, Tourangeau R, Where do we go from here? Nonresponse and social measurement, Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Sci 645 (2013) 222–236, doi: 10.1177/0002716212464191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Karliner LS, Jacobs E. a., Chen AH, Mutha S, Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited english proficiency? A systematic review of the literature, Health Serv. Res 42 (2007) 727–754, doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Angelelli C, Healthcare Interpreting Explained, 1st ed., Routledge, London, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Diamond LC, Schenker Y, Curry L, Bradley EH, Fernandez A, Getting by: Underuse of interpreters by resident physicians, J. Gen. Intern. Med 24 (2009) 256–262, doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0875-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Karliner LS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gildengorin G, The language divide: The importance of training in the use of interpreters for outpatient practice, J. Gen. Intern. Med 19 (2004) 175–183, doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Papic O, Malak Z, Rosenberg E, Survey of family physicians’ perspectives on management of immigrant patients: Attitudes, barriers, strategies, and training needs, Patient Educ. Couns 86 (2012) 205–209, doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Butler R, Monsalve M, Thomas GW, Herman T, Segre AM, Polgreen PM, Suneja M, Estimating time physicians and other health care workers spend with patients in an intensive care unit using a sensor network, Am. J. Med 131 (972) (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.03.015.e9-972.e15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Squires A, Youdelman M, Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act: Strengthening language access rights for patients with limited English proficiency, J. Nurs. Regul 10 (2019) 65–67, doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(19)30085-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Derr AS, Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review, Psychiatr. Serv 67 (2016) 265–274, doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500004.l [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]