Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the long-term outcomes of SLNB for HNCM

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study

Setting:

Tertiary academic medical center

Subjects and Methods:

Longitudinal review of 356 patient cohort with HNCM undergoing SLNB from 1997 to 2007.

Results:

Descriptive characteristics include mean age 53.5±19 years, 26.8% female, median follow-up 4.9 years, and mean Breslow depth 2.52±1.87mm. 75 (21.1%) patients had a positive SLNB. Among patients undergoing CLND following positive SLNB, 20 (27.4%) had at least one additional positive NSLN(s). 18 patients with local control and negative SLNB developed regional disease, indicating a false omission rate 6.4%, including 10 recurrences in previously unsampled basins. 10-year overall survival (OS) and melanoma specific survival (MSS) were significantly greater in the negative SLN cohort (OS: 61%; Cl: 0.549–0.677; MSS: 81.9%, 95% Cl: 0.769–0.873) than the positive SLN (OS: 31%, Cl 0.162–0.677; MSS: 60.3%, Cl: 0.464–0.785) and positive SLN/positive NSLN (OS: 8.4%, Cl: 0.015–0.474; MSS: 9.6%, Cl: 0.017–0. 536) cohorts. OS was significantly associated with SLN positivity (hazard ratio (HR) 2.39, p<0.01), immunosuppression (HR 2.37; p<0.01), angiolymphatic invasion (HR 1.91; p<0.01), and ulceration (HR 1.86; p<0.01). SLN positivity (HR 3.13, p<0.01), angiolymphatic invasion (HR 3.19, p<0.01) , and number of mitoses (p=0.0002) are significantly associated with MSS. Immunosuppression (HR 3.01, p<0.01) and SLN status (HR 2.84, p<0.01) were associated with recurrence free survival, and immunosuppression was the only factor significantly associated with regional recurrence (HR 6.59; p<0.01).

Conclusions:

Long-term follow up indicates that SLNB showcases durable accuracy and prognostic importance for cutaneous HNCM.

Keywords: melanoma, head and neck, sentinel lymph node biopsy, false omission, otolaryngology, cutaneous

Introduction:

Modern sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was first described by Morton in 1992.1,2 SLNB has since been widely employed for clinically lymph node negative (cN0) intermediate depth melanomas and has allowed earlier detection, improved locoregional staging, expeditious primary and adjuvant treatment implementation, and risk-stratification for investigative therapies. Perhaps corresponding to the adoption of SLNB, long-term survival in melanoma has improved over the last four decades.3–5 The initial Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-I) demonstrated earlier detection and treatment of nodal micrometastases conferred disease free survival (DFS) and melanoma specific survival (MSS) advantages over observation.6–10 Sentinel lymph node (SLN) status represents the strongest prognosticator in early-stage melanomas for overall survival (OS), MSS, and DFS, independent of Breslow depth.6,7,11

Notwithstanding, early studies questioned SLNB’s accuracy, safety, and prognostication for head and neck cutaneous melanoma (HNCM), citing discordant head and neck (HN) lymphatic drainage, higher false omission rates, higher recurrence rates, significantly lower SLN-positivity, and two long-term SLNB-related cranial nerve (CN) XI injuries.5,9,12–11 Erman, et. al. changed the paradigm for HNCM by demonstrating 99.7% SLN identification, 19.6% SLN-positivity, and 4.2% false omission, without clinically significant CN or vascular injuries.4,9,15,17 Upholding its safety, no permanent SLNB-related CN VII injuries have been reported to-date in large HNCM series, despite 26% of SLN’s in HNCM mapping to the parotid.4,15,17,18 While preceding large HNCM studies failed to establish SLNB’s prognostic importance, 10,19,20 Erman, et. al. affirmed SLNB-positivity as the most prognostic clinicopathologic predictor of both RFS (HR 4.23, p<0.0001) and OS (HR 3.33, p<0.0001) for HNCM,9 and HN SLNB has since been routinely and safely employed.

Delayed melanoma recurrences are frequent, with a median time-to-recurrence nearly 2 years following a negative SLNB, and 10.8% of all recurrences occur beyond 5 years.3 Therefore, extended follow-up is crucial to assess long-term accuracy and prognostication. Thus, 10 years following closure of Erman’s patient-accrual and 25 years after Morton’s first modern SLNB description, this study reports long-term SLNB accuracy, safety, and survival outcomes for HNCM.1,9

Methods:

This study was conducted with University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approval. 356 patients from the prospectively-collected HNCM database featured in Erma n’s 2012 study, who underwent SLNB from 1997 to 2007, were longitudinally reviewed to determine long-term outcomes, using identical inclusion criteria.9 Surgical techniques, lymphoscintigraphy, intraoperative gamma-radiotracer detection, intradermal vital blue dye injection, CN monitoring, and dermatopathologic processing are previously described.9 Immediate completion lymph node dissection (iCLND) was recommended for patients with SLNB-positivity with consideration for adjuvant therapies. Patients with negative SLN(s) were monitored clinically and offered “salvage” CLND for clinically or radiographically-apparent recurrences.9 Data were collected from the initial clinical evaluation date through September 30, 2017 including vital and disease status, radiologic studies, pathologic analyses, operative interventions, and adjuvant treatments. Data acquisition encompassed medical record review, patient telephone interview, fax/telephone communication with referring physician(s), and Social Security Death Index review.

Outcome measures included OS, MSS, progression-free survival (PFS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), regional-recurrence-free survival (regional-RFS), and distant-recurrence-free survival (distant-RFS). Other data compiled included SLNB result, non-sentinel lymph node (NSLN) status, time-to-recurrence, site of recurrence, salvage interventions, total local/regional/distant disease burden, and details of health status or mortality. Time-to-event endpoints were calculated from SLNB date. As an exception, NSLN-positivity was determined upon iCLND, and analyses dependent upon NSLN status were calculated from iCLND date. Survival outcomes were determined using Kaplan-Meier (KM) method. Specifically, OS was characterized as the time elapsed from SLNB to death or last clinical follow-up, defined as the most recent disease- and vital-status assessment performed by a qualified practitioner. MSS was calculated from the SLNB date until melanoma-specific mortality, which was defined as death in the context of active distant metastasis without another known cause. RFS, regional-RFS, and distant-RFS describe the time elapsed from SLNB to the date of each recurrence event or last follow-up. In the absence of a recorded outcome event, patients were censored at last follow-up. As detection of false negatives (FN) is partly determined by follow-up, a lower bound for false omission was calculated by (FN/(FN + True Negatives)), and FN rate was calculated by (FN/(FN + True Positives)).

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess associations between patient, tumor, SLNB, and NSLN characteristics and the time-to-event endpoints. Multivariable models were constructed for analyses, and P-values and hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using Wald tests. A backward selection model building procedure was used to iteratively remove non-statistically significant variables until only significant variables remained. Variables considered in the multivariable models include ECS, SLN positivity, Breslow depth, mitoses, immunosuppression, ulceration, angiolymphatic invasion (ALI), age at diagnosis, perineural invasion/neurotropism (PNI), and regression. A variable’s HR is in part dependent on measurement scale. To make comparisons less scale-dependent, the order of variables was determined by standardizing the HR using standard deviation. The term ‘statistical significance’ denotes p-value <0.05.

Results:

356 HNCM patients underwent SLNB from 1997 to 2007 and were followed longitudinally with 4.9 years median follow-up. Follow-up was greater than 5 years in over 50% of patients and greater than 10 years in 35%. Mean age at diagnosis was 53.5 ± 19.0 years. Mean tumor Breslow depth was 2.52 ± 1.87 mm. During SLNB, 2.25 ± 1.53 mean SLNs were extracted from 1.77 ± 0.94 mean sampled lymphatic basins per patient. Lymphatic basins outside of the HN region were considered distant metastases. 75 of 356 patients (21.1%) showcased SLN-positivity, and all but 2 (97.3%, n=73) underwent iCLND. 20 SLN-positive patients also showcased at least one positive NSLN detected during iCLND.9 Only 12 of 75 patients with regional nodal micrometastasis underwent adjuvant systemic therapies (predominantly interferon-alpha), and 2 of 75 underwent adjuvant radiation. Table 1 showcases complete descriptive statistics and patient characteristics.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics and patient characteristics for the study sample (n=356).

| Characteristic | Mean or Frequency(% of non-missing) | Standard Deviation, Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 53.5 | 19.0, (2.0, 87.0) |

| Sex: Female | 95 (26.8%) | |

| Breslow Depth (mm) | 2.5 | 1.9, (0.0, 15.0) |

| Number of Cervical Lymphatic Basins Sampled | 1.8 | 0.9, (0.0, 5.0) |

| Angiolymphatic Invasion (ALI) | 35 (9.9%) | |

| Immunosuppression | 12 (3.4%) | |

| Ulceration | 67 (18.8%) | |

| Number of Mitoses | 3.9 | 5.9, (0.0, 50.0) |

| Number of Sentinel Nodes Extracted | 2.3 | 1.5, (1.0, 11.0) |

| Sentinel Node Result: Positive, Negative | 75 (21.1%), 281 (78.9%) | |

| Non-sentinel Lymph Node (NSLN) Status:Positive | 20 (27.4% of iCLND patients) |

18 SLNBs were falsely negative, representing a 6.4% false omission rate and 19.4% FN rate. Among the 18 FNs, 10 (56%) recurred in the same lymphatic basin as a previous negative SLN, including 1 patient who recurred in both previously interrogated and uninterrogated ipsilateral neck levels. Remaining patients recurred in only previously uninterrogated ipsilateral neck levels (n=8). There were no contralateral or bilateral recurrences. Incorporating NSLN-positivity determined from iCLND, delayed recurrences, and FNs, 46 total patients (12.9%) showcased “corrected” NSLN-positivity with 4.9 years median follow-up. Eight FN recurrences required more extensive salvage CLND, including two salvage modified radical neck dissections, than if iCLND had been performed based on traditionally recommended basins by primary site12 or if all SLN-containing basins had been immediately dissected. Four FN’s resulted in macroscopic nodal recurrences outside of both traditionally-recommended-12 and SLN-containing basins. Including both SLN-negative and SLN-positive cohorts, 17 patients underwent systemic therapies and 13 underwent radiation with or without salvage surgery following macroscopic regional and/or local recurrence(s).

Major complications after iCLND were rarely encountered. Three patients (4.1%) developed post-operative hematomas requiring surgical intervention, while three surgical site seromas, one chyle leak, and one sialocele (treated with glycopyrrolate) all successfully resolved with conservative management. There was also one phrenic nerve injury, one lingual nerve injury, one inpatient fall-related wrist fracture, and one urinary tract infection. There were no permanent CN injuries.21 One case of mild submental lymphedema following iCLND was noted, resolving spontaneously within 4 postoperative weeks. Perioperative myocardial infarctions, strokes, or deaths were not encountered.

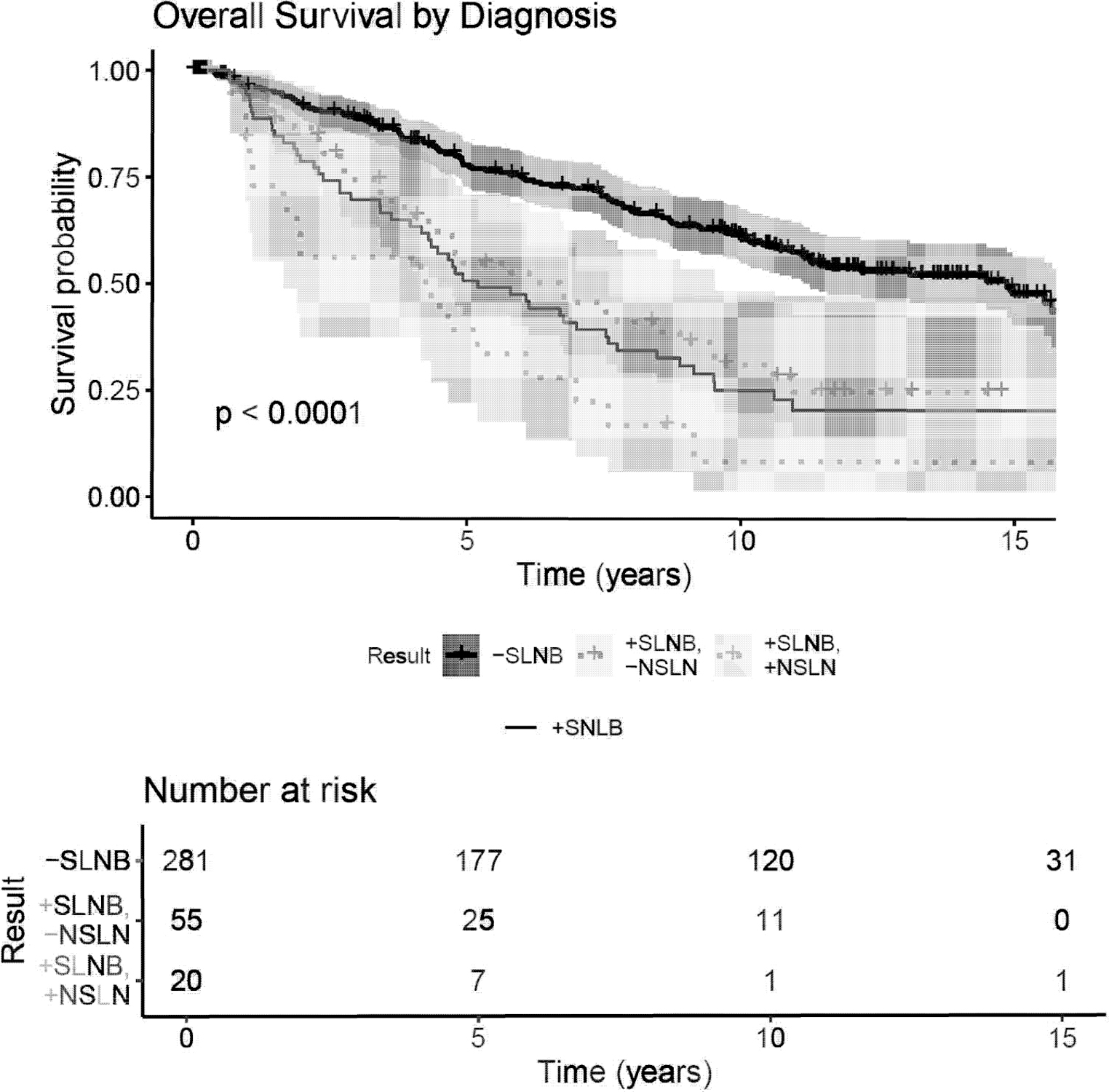

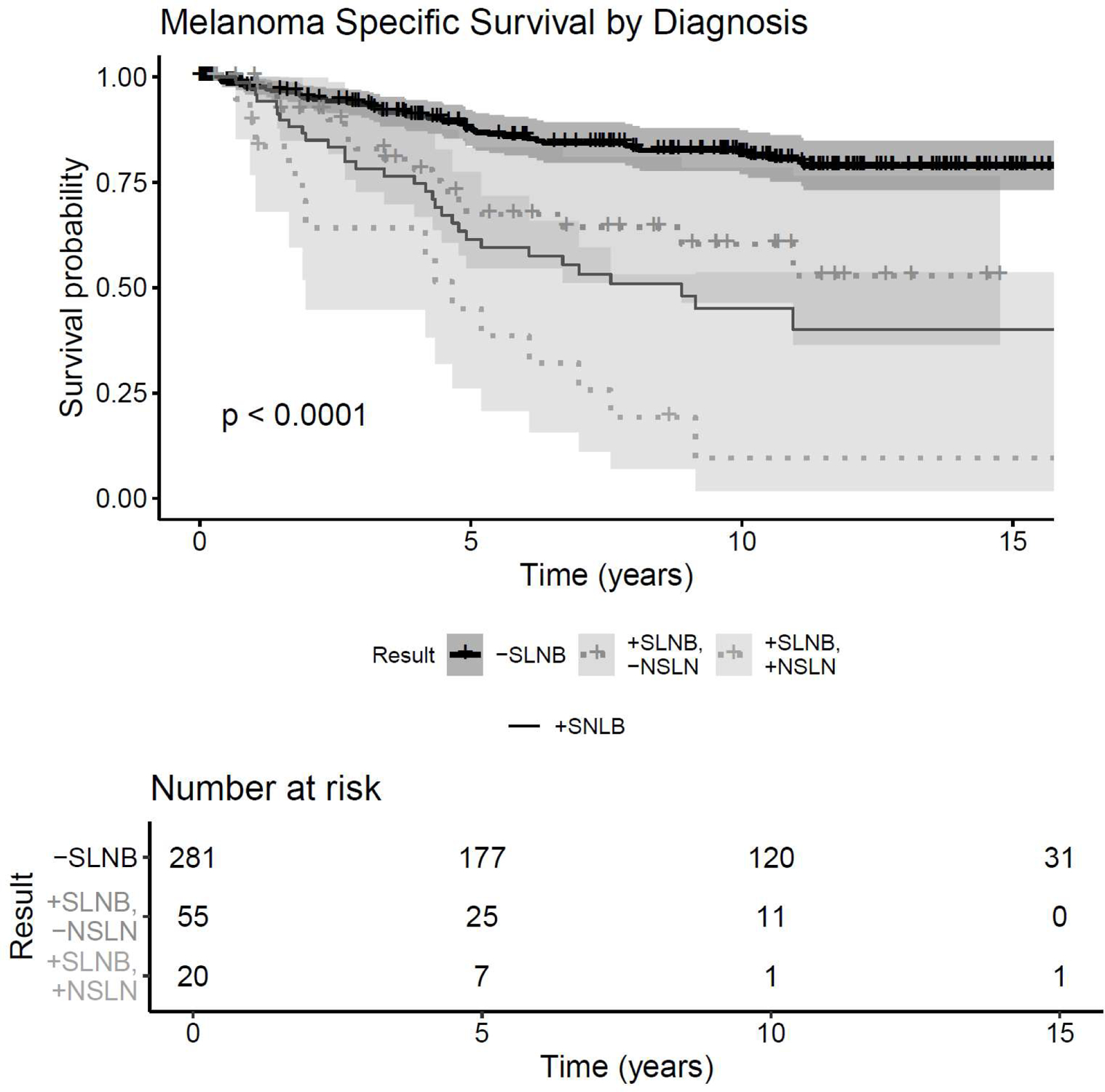

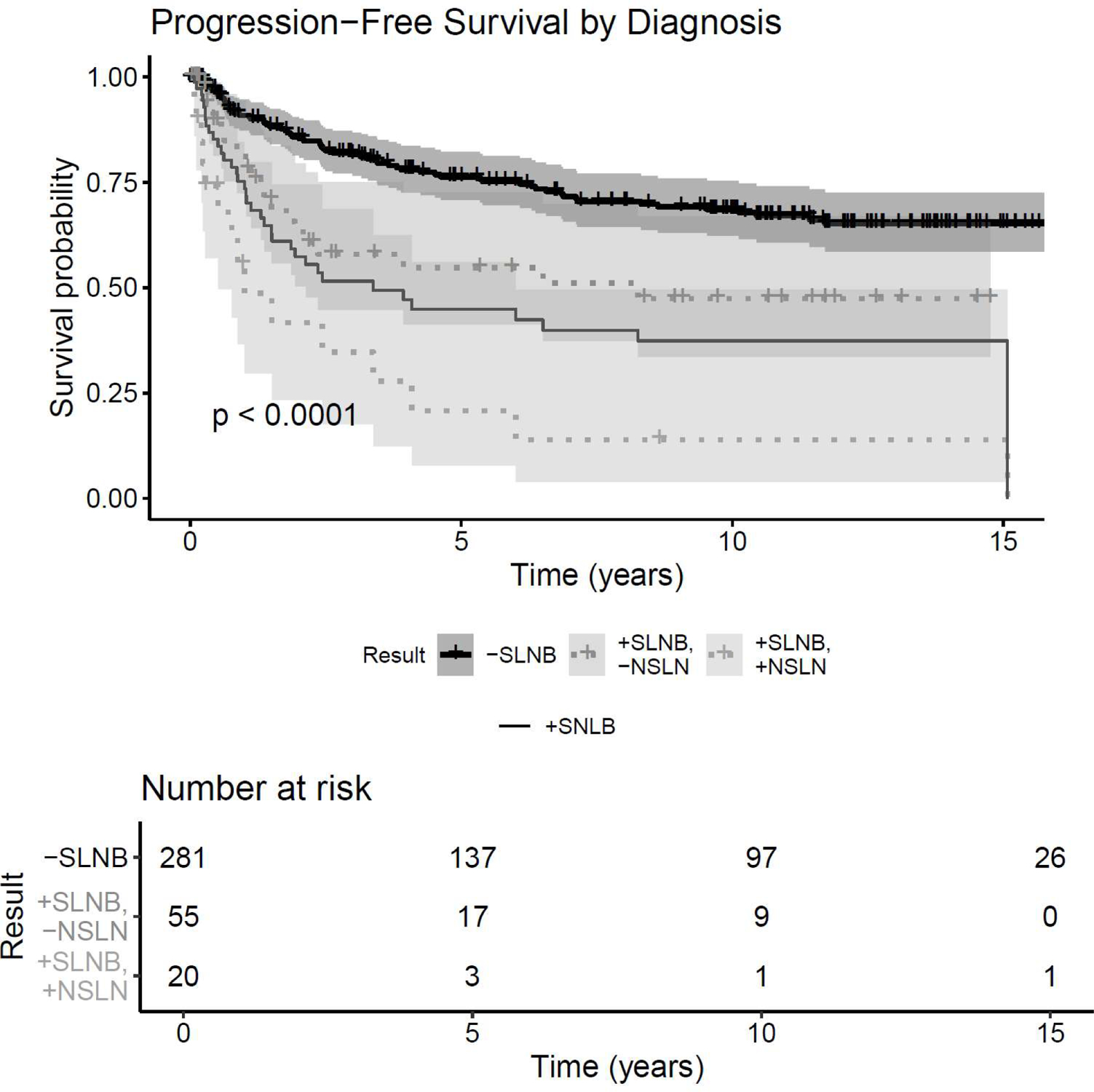

By univariable analysis, OS, MSS, PFS, regional-RFS, and distant-RFS were each significantly improved in the negative SLN group over the positive SLN cohort and positive SLN/positive NSLN cohort (Figure 1a; Figure 1b[Online only]). Median OS in the negative SLN cohort was 14.9 years (95% Cl: 11.14, not reached) versus 5.2 years in the positive SLN cohort (95% Cl: 4.16, 7.53). 10-year OS was greater in the negative SLN cohort (61%; 95% Cl: 0.549–0.677) than the positive SLN/negative NSLN cohort (31%, 95% Cl 0.200–0.485), which was in turn was distinctly higher than OS survival for patients with positive SLNB/positive NSLN (8.4%, 95% Cl: 0.015–0.474). The same relationship held true for 10-year MSS, with an even sharper decline in survival estimates from negative SLNB (81.9%; 95% Cl: 0.769–0.873) to positive SLNB/negative NSLN (60.3%; 95% Cl: 0.464–0.785) and finally positive SLNB/positive NSLN (9.6%; 95% Cl: 0.017–0. 536). 10-year OS and MSS estimates are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1a.

Survival and recurrence Kaplan-Meier curves by SLN status. X-axis: time (years), Y-Axis: Survival Probability. A) OS, B) MSS, C) Progression free survival. “-SLNB”=negative SLNB; “+SLNB”= positive SLNBs; “+SLNB/-NSLN”=positive SLNB/negative NSLN; “+SLNB/+NSLN”= positive SLNB/positive NSLN(s)

Table 2:

10 year Survival Estimates based on Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) and Non-Sentinel Lymph Node (NSLN) Status.

| 10 year Overall Survival | Survival Estimate | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| Negative SLN | 61.0% | 0.549, 0.677 |

| Positive SLN only | 31.1% | 0.200, 0.485 |

| Positive SLN, Positive NSLN | 8.4% | 0.015, 0.474 |

| 10 year Melanoma Seecific Survival | Survival Estimate | 95%CI |

| Negative SLNB | 81.9% | 0.769, 0.873 |

| Positive SLNB only | 60.3% | 0.464, 0. 785 |

| Positive SLNB, Positive NSLN | 9.6% | 0.017, 0. 536 |

By multivariable analysis, OS was negatively associated with SLN-positivity (HR 2.39, p<0.0001), immunosuppressed status (HR 2.37; p=0.02), ALI (HR 1.91, p=0.01), tumor ulceration (HR 1.86; p=0.002), increasing Breslow Depth (HR 1.1, p= 0.03), and age at diagnosis (HR 1.03, p<0.0001). Similarly, by multivariate analysis MSS was negatively associated with SLN-positivity (HR 3.13, p<0.0001), ALI (HR 3.19, p< 0.0001), and number of mitoses (HR 1.06, p= 0.0002). RFS was negatively associated with immunosuppression (HR 3.01, p=0.007), SLN-positivity (HR 2.84, p<0.0001), ALI (HR 2.77, p=0.0001), tumor ulceration (HR 2.40, p<0.0001), and age (HR 1.02, p=0.002). Immunosuppression was the only factor associated with regional recurrences (HR 6.59, p=0.003), although there were notably few immunosuppressed patients (n=12). A comprehensive summary of risk factors significantly associated with various survival outcomes is shown in Table 3.

Table 3:

Risk Factors Significantly Associated with Survival Outcomes by multivariable analysis (ordered from most adversely associated to least adversely associated by standardized hazard ratio)

|

Overall Survival N=353, Number of events=159 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| Age at Diagnosis (per year) | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | <0.0001 |

| Sentinel Node Positivity | 2.39 | 1.17–3.11 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor Ulceration | 1.86 | 1.26–2.75 | 0.002 |

| Angiolymphatic Invasion (ALI) | 1.91 | 1.17–3.11 | 0.01 |

| Breslow Depth (per mm) | 1.10 | 1.01–1.20 | 0.03 |

| Immunosuppression | 2.37 | 1.14–4.93 | 0.02 |

|

Melanoma Specific Survival N=335, Number of events=74 | |||

| Risk Factors | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| Sentinel Node Positivity | 3.13 | 1.92–5.12 | <0.0001 |

| Angiolymphatic Invasion (ALI) | 3.19 | 1.81–5.63 | <0.0001 |

| Number of Mitoses | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | 0.0002 |

|

Recurrence Free Survival N=356, Number of events=103 | |||

| Risk Factors | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| Sentinel Node Positivity | 2.84 | 1.85–4.35 | <0.0001 |

| Age at Diagnosis (per year) | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.002 |

| Tumor Ulceration | 2.40 | 1.55–3.71 | <0.0001 |

| Angiolymphatic Invasion (ALI) | 2.77 | 1.66–4.65 | 0.0001 |

| Immunosuppression | 3.01 | 1.35–6.74 | 0.007 |

|

Regional Recurrence Free (non-confounded by local recurrence) Survival N=356, Number of events=24 | |||

| Risk Factors | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| Immunosuppression | 6.59 | 1.93–22.52 | 0.003 |

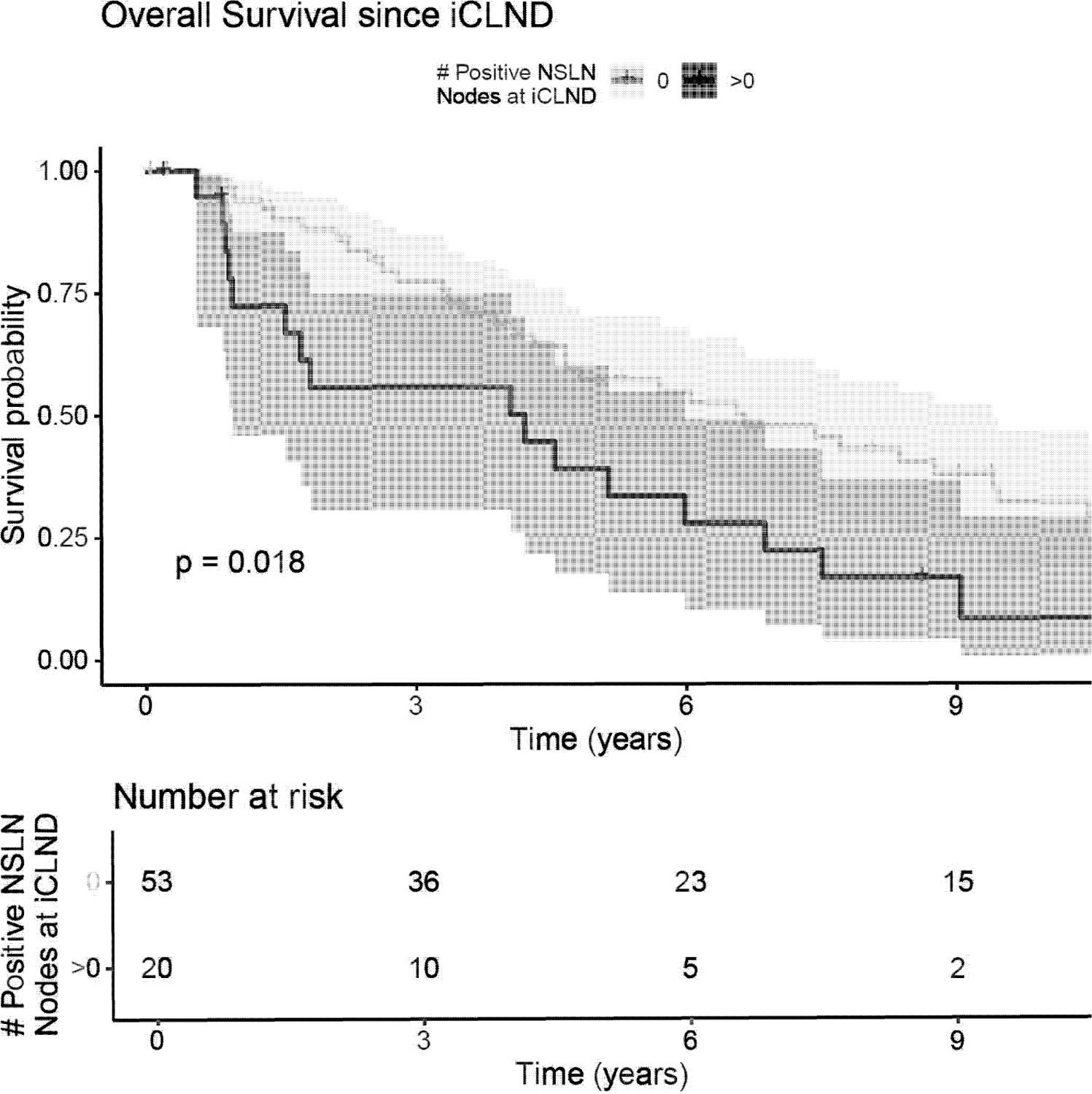

NSLN-positivity represents an important clinicopathologic factor with unique survival implications and was thus examined, as surgical management of NSLNs is controversial.22–25 20 of 73 patients who underwent iCLND for SLNB-positivity also displayed NSLN-positivity. Both the presence and increasing number of positive NSLNs exhibited significantly negative associations with OS, MSS, and RFS (Table 4). Significantly worse OS was associated with NSLN-positivity compared to micrometastases confined to SLN(s) (p=0.02) (Figure 2).

Table 4:

Effects of NSLN-positivity on OS, MSS, and RFS among patients with positive SLNB who underwent iCLND, adjusting for age.

| Non-sentinel Lymph Node Positivity in Patients undergoing CLND (n=73) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival, number of events=48 | |||

| Risk Factors | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| Positive NSLN | 1.98 | 1.07, 3.65 | 0.03 |

| Total Number of Positive NSLN | 1.48 | 1.16, 1.89 | 0.001 |

| Melanoma Specific Survival, number of events=30 | |||

| Positive NSLN | 3.20 | 1.54, 6.62 | 0.002 |

| Total Number of Positive NSLN | 1.67 | 1.27, 2.19 | 0.0003 |

| Recurrence Free Survival, number of events=35 | |||

| Positive NSLN | 2.68 | 1.34, 5.36 | 0.005 |

| Total Number of Positive NSLN | 1.14 | 1.06, 1.23 | 0.0004 |

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier curve for OS among patients with positive SLN having undergone iCLND, stratified by the number of positive NSLNs. X-axis: time (years), Y-Axis: Survival Probability. “O” = NSLNs negative, “>0”= 1 or more positive NSLN(s)

Discussion:

The landmark publication by Erman, et. al. established SLNB’s safety, reliability, and prognostic importance for HNCM and unified SLNB as the standard of care for cN0 melanoma in all anatomic sites.9,26–29 Since then, studies at other institutions have replicated and confirmed these findings. 9,30–32 We present an updated analysis of Erman’s large single-institution HNCM cohort9 with long-term follow-up, which validates SLNB’s long-term safety, accuracy, and prognostic utility for HNCM. SLN-status remains highly prognostic for OS, MSS, RFS, and regional-RFS. Further, the spread of regional metastases beyond the SLN (i.e. to NSLNs) portends an abysmally poor prognosis.

Of the parameters defining SLNB accuracy including SLN identification and positivity rates, only the false omission rate’s implications evolve temporally due to the potential for additional regional recurrences with time following a negative SLNB.9 Erman initially reported a 4.2% false omission rate at 35 months, which was superior to historically published HNCM SLNB false omission rates (9.3%)10,18–20,33–37 and likewise compared favorably to rates reported in large studies consisting primarily of truncal and extremity melanomas (3.4–4.7%).2,38,39

Other studies exclusively reporting HNCM outcomes provide further credence to favorable long-term SLNB false omission rates, including Parrett (5.2%, 72 months) and Evrard (7.1%, 47 months).30,32 Studies encompassing all primary sites with 42 months follow-up or greater (Table 52,3,14,30,32,33,40–54) report false omission rates ranging from 0.6% to 9.4%. Pooled data from these 21 studies, drawing from over 10,600 negative SLNBs from all sites, yield a cumulative false omission rate of 3.7%.2,3,14,30,32,33,35,40–54 Some studies have defined FN SLNB to include same-basin recurrences only.42,53,54 However, this definition fails to require SLNB to accurately predict the pathologic status of the entire remaining unsampled regional nodal field.1 Therefore, we define a FN as nodal recurrence in any regional basin following negative SLNB in the absence of confounding simultaneous local, in-transit, or dermal-metastatic recurrence and yet showcase a low long-term false omission rate. Notwithstanding, only 3.5% of patients in this cohort recurred in a previously interrogated, negative lymphatic basin. While early studies reported higher false omission rates in HNCM relative to truncal and extremity sites, our low 6.4% 10-year false omission rate upholds SLNB’s durable accuracy and confirms that no such discrepancy exists 6,16,17,38,39,55.

Table 5:

Long Term SLNB False Omission Rates Reported in Studies with at least 42 months Follow-up: False omission calculated (where available) from reported false and true negatives (FN/FN+TN).

| Cohorts of Exclusively Head and Neck Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (year published) | False Omission Rate | Total Patients (NT) | Total HNCM Patients (NHN) (%) | Follow-up (months) |

| Current Study | 6.4% (18/[18+2631) | 356 | 356 (100%) | 58 |

| Teltzrow (2007)33 | 9.4% (8/[8+771) | 106 | 106 (100%) | 46.9 |

| Parrett (2012)32 | 5.2% (17/[17+3081) | 365 | 365 (100%) | 96 |

| Evrard (2018)30 | 7.1% (7/[7+941) | 124 | 124 (100%) | 46.6 |

| Subsets of only Head and Neck Patients within Large Cohorts of All Primary Sites | ||||

| Study (year) | False Omission Rate | Total Patients (Nr) | Total HNCM Patients (NHN) (%) | Follow-up (months) |

| Carlson (2008)14 | 8.0% (Self-reported) | 1287 | 176 (13.7%) | 44.3 |

| Cohorts of All Primary Sites | ||||

| Study (year) | False Omission Rate | Total Patients (NT) | Total HNCM Patients (NHN) (%) | Follow-up (months) |

| Doting (2002)40 | 1.3% (2/[2+147]) | 200 | 22 (11%) | 47 |

| Fincher (2003)41 | 0.6% (1/[1+159]) | 198 | 30 (15%) | 45 |

| Estourgie (2003)42 | 6.3% (12/[12+1781) | 250 | 15 (6%) | 72 |

| Vuylsteke (2003)43 | 2.4% (4/[4+165], | 209 | 16 (8%) | 72 |

| Yee (2005)44 | 2.6% (22/[22+8241) | 1012 | 95 (11%) | 42.1 |

| Leong (2005)45 | 2.7% (8/[8+290)) | 363 | 51 (14%) | 58.8 |

| Nowecki (2006)46 | 5.8% (57 /[57+922]) | 1207 | 15 (1.2%) | 43 |

| Morton (2006)2 | 4.0% (26/[26+6161) | 769 | (16.2%) | 60 |

| Cascinelli (2006)47 | 5.0% (47 /[47+885]) | 1108 | 46 (4.1%) | 61.1 |

| Kettlewell (2006)48 | 3.3% (12/[12+3551) | 482 | 48 (10%) | 42 |

| Corrigan (2006)49 | 9.4% (8/[8+771) | 149 | 12 (8.1%) | 50 |

| Emery (2007)50 | 2.6% (4/[4+151]) | 177 | 30 (17%) | 49 |

| Carlson (2008)14 | 3.3% (35/[35+1025]) | 1287 | 176 (13.7%) | 44.3 |

| Riber-Hanson (2008)51 | 4.5% (3/[3+631) | 93 | 5 (5.4%) | 43.5 |

| Testori (2009)52 | 3.3% (36/[36+ 1048]) | 1313 | 84 (6.4%) | 54.2 |

| Scroggins (2010)53 | 3.0% (59/[59+ 1906]) | 2451 | Not Reported (NR) | 54 |

| Veenstra (2011)54 | 1.9% (10/[10+5241) | 665 | NR | 54 |

| Jones (2013)3 | 4.0% (21/[21 +499]) | 520 (only negative SLNB included in study) | 110 (21.2%) | 61 |

| Cumulative Pooled Data | 13.7% (395/[395+10,224]) | 12,456 | ||

Given historical concerns of unpredictable, dissonant cutaneous HN lymphatic drainage, delayed regional recurrence patterns following a FN SLNB are also important. 10 (55.6%) of the 18 FN cases recurred in the same lymphatic basin as previously extracted negative SLN(s). Compared to Erman’s report, in which 75% of FN SLNBs recurred in previously sampled basin(s), the current analysis shows a greater proportion of recurrences in previously unsampled basins (44.4%). Moreover, with 8-years of median follow-up, Parrett observed FN recurrences even more frequently in previously uninterrogated basins (58.8%).32 Therefore, while SLN-negativity remains highly predictive of durable regional disease control with long-term follow-up, a small minority of patients appear susceptible to regional recurrence following negative SLNB, perhaps with an increasing tendency for recurrence in previously unsampled basins with time. An additional cost of macroscopic locoregional failure is the potential need for more extensive treatment or additional modalities employed during salvage. Eight FN patients required salvage CLND that was more extensive than the theoretical iCLND recommendation based upon primary site12 or if all SLNs had been positive. 30 total patients underwent salvage surgery and a combination of systemic therapies and/or radiation following macroscopic locoregional recurrence(s).

The immense independent prognostic importance of both SLN and NSLN status in cN0 melanoma has been well-established.6,7,9,11,22,24,56–58 Gershenwald’s landmark 1999 study established SLN histopathologic status as the strongest prognosticator in early-stage trunk and extremity melanomas for OS, MSS, and DFS.6,7,11 After prior large studies failed to establish a similar relationship in HNCM, 10,18,19 Erman substantiated SLNB’s prognostic importance in HNCM, demonstrating positive SLN status to be the most prognostic clinicopathologic predictor of both RFS (HR 4.23, p<0.0001) and OS (HR 3.33, p<0.0001).9 Perhaps most importantly, the final analysis of MSLT-1 confirmed that among the SLNB cohort, SLN histopathologic status continues to demonstrate large associations with survival and disease recurrence with long-term follow-up.6

NSLN positivity is also known to independently portend markedly worse OS, MSS, and DFS compared to regional disease confined to the SLNs.22,24,56,57 Reintgen found that NSLN-positivity was associated with worse survival compared to an equal number of positive SLNs and demonstrated the larger association of the mere presence of positive NSLNs over incrementally increasing total number of positive regional lymph nodes.58 In patients undergoing iCLND following a positive HN SLNB, Erman demonstrated 25% to have additional positive NSLNs, which is also consistent with other HN studies and large truncal and extremity studies.9,22,26,32,59

Our study shows that every 10-year survival parameter examined (OS, RFS, regional-RFS, distant-DFS, PFS, and MSS) was significantly and drastically diminished in the positive SLN cohort and even worse for patients with NSLN-positivity. Whereas patients without regional nodal metastasis showcased 61% 10-year OS and 81.9% 10-year MSS, OS fell drastically to 31% and MSS to 60.3% with SLN-positivity. Further, if patients showcased both SLN- and NSLN-positivity, OS (8.4%) and MSS (9.6%) at 10 years plummeted to abysmal values.

Concordant with the long-term results of MSLT-1, our findings demonstrate that SLN-positivity remains a strong long-term prognosticator of OS (HR 2.39, p<0.0001) and MSS (HR 3.13, p<0.0001) in HNCM, keeping with numerous studies including truncal, extremity, and HNCM data.6,7,9,32 Likewise, this study confirms that relative to patients completely lacking nodal metastases and relative to those whose regional disease is confined to SLNs, both the presence (vs +SLN only, OS: HR 1.98, p=0.03; MSS: HR 3.20, p=0.002; RFS: HR 2.68, p=0.005) and increasing numbers of positive HN NSLNs (vs +SLN only, OS: HR 1.48, p=0.001; MSS: HR 1.67, p=0.0003; RFS: HR 1.14, p=0.0004) showcase significantly worse OS, MSS, and RFS. The significant negative associations of NSLN positivity with OS, MSS, and RFS is also upheld when only examining patients with SLN-positivity. It is theorized that distinctly more aggressive tumor biology is required to evade the SLN’s immunologic barrier to facilitate NSLN involvement.24,58 Given the adverse association of NSLN-positivity with recurrence and survival, NSLN metastasis has been advocated for inclusion in future AJCC guideline iterations.22,24,57,58 More aggressive behavior of melanoma with NSLN involvement and resultant worsened survival, comparable to that of bulky palpable nodal disease, are frequently cited arguments against immediate iCLND following a positive SLN, despite a 70% improvement in regional recurrence and consequent DFS benefit over observation in MSLT-2.22,57,58 A randomized controlled study evaluating iCLND’s effect on survival following a positive SLNB for HNCM versus observation is unlikely to be undertaken, and HNCM has been underrepresented in large studies to date.22 This study’s retrospective longitudinal design precluded an observation arm following positive SLNB. In light of MSLT-ll’s results, the importance of NSLN positivity, early DFS, and the role of iCLND in cN0 HNCM requires further study.22

Since 2011 the US FDA has approved multiple molecularly-targeted and immune therapies for stage Ill and IV melanoma, which has transformed advanced melanoma outcomes.60–68 A limitation of the data presented herein is that it predates use of effective systemic therapies, but the evolving applications of these agents may ultimately redefine surgery’s future role in melanoma. However, the decision for adjuvant therapy is complex, and the optimal use of new systemic agents is not yet uniformly established. Given the high risk of NSLN-positivity in HNCM, histopathologic variables provided by iCLND could direct systemic therapy or facilitate risk stratification for clinical trial enrollment. The timing of therapy, patient health conditions, treatment toxicities, and the potential benefit in later stage disease are vital considerations prior to the initiation of adjuvant therapy.

Other notable study limitations include retrospective analysis of a single tertiary institutional experience. Use of data from a large melanoma referral center allowed for greater sample size and ensured consistency in technique; however, inter-institutional and community practice may showcase greater variability. Limitation to this previously reported cohort was necessary to analyze long-term follow up, which was this study’s stated goal. Interim advances in SLNB, widespread use of CN electrophysiologic monitoring, establishment of high-volume multidisciplinary cutaneous oncology centers, advances in lymphoscintigraphy, and the advent of SPECT/CT during the decade elapsed since this study’s enrollment closed must be considered. These advances likely further improve safety, accuracy, and prognostic benefit for HN SLNB.4,9,11,26,69,70

Conclusions:

SLNB remains safe, accurate, and prognostic for HNCM with long-term follow-up. While SLN status remains highly prognostic for OS, MSS, and regional disease status. However, prolonged clinical observation may be warranted due to the delayed recurrence risk, including the slight tendency for recurrence in previously uninterrogated lymphatic basins and potential need for more extensive and/or multimodality salvage treatments. Regional metastasis beyond the SLN (i.e. to NSLNs) portends an abysmally poor prognosis. Survival improvements arising from novel technologies and systemic therapies promise continued evolution of the roles of regional staging, DFS, regional DFS, and surgery in the treatment of metastatic melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1b (Online Only). Survival and recurrence Kaplan-Meier curves by SLN status. X-axis: time (years), Y-Axis: Survival Probability. D) Local-RFS, E) Regional-RFS, F) Regional-RFS lacking confounding local, dermal-metastatic, and/or satellite recurrences, G) Distant-RFS. “-SLNB”=negative SLNB; “+SLNB”= positive SLNB

Acknowledgements:

We thank Nisha Meireles for database and data management

Funding:

Author K.J.K is supported by NIH grant T32 DC005356.

Abbreviations:

- Cl

Confidence interval

- cN0

Clinically N0

- CN

Cranial nerve

- CLND, iCLND

Completion lymph node dissection (i.e. completion neck dissection), immediate completion lymph node dissection

- DFS

Disease free survival

- HN

Head and neck

- HNCM

Head and neck cutaneous melanoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- MSS

Melanoma specific survival

- SLN

Sentinel Lymph Node

- NSLN

Non-sentinel lymph node

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression free survival

- RFS

Recurrence free survival

- Distant-RFS

Distant Recurrence free survival

- Regional-RFS

Regional Recurrence free survival

- SLNB

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

- STDEV

Standard deviation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Meeting Information: This work was previously presented at the 2018 AAO-HNSF meeting (Atlanta, GA, USA, October 7–10’ 2018).

Level of Evidence: III

References:

- 1.Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127(4):392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1307–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones EL, Jones TS, Pearlman NW, et al. Long-term follow-up and survival of patients following a recurrence of melanoma after a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy result. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmalbach CE, Bradford CR. Is sentinel lymph node biopsy the standard of care for cutaneous head and neck melanoma? laryngoscope. 2015;125(1):153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMasters KM, Reintgen DS, Ross Ml, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: how many radioactive nodes should be removed? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8(3):192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, et al. Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I or II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(3):976–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton DL, Wanek L, Nizze JA, Elashoff RM, Wong JH. Improved long-term survival after lymphadenectomy of melanoma metastatic to regional nodes. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1134 patients from the John Wayne Cancer Clinic. Ann Surg. 1991;214(4):491–499; discussion 499–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erman AB, Collar RM, Griffith KA, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is accurate and prognostic in head and neck melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118(4):1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leong SP, Accortt NA, Essner R, et al. Impact of sentinel node status and other risk factors on the clinical outcome of head and neck melanoma patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(4):370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoffels I, Boy C, Poppel T, et al. Association between sentinel lymph node excision with or without preoperative SPECT/CT and metastatic node detection and disease-free survival in melanoma. JAMA. 2012;308(10):1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien CJ, Uren RF, Thompson JF, et al. Prediction of potential metastatic sites in cutaneous head and neck melanoma using lymphoscintigraphy. Am J Surg. 1995;170(5):461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willis Al, Ridge JA. Discordant lymphatic drainage patterns revealed by serial lymphoscintigraphy in cutaneous head and neck malignancies. Head Neck. 2007;29(11):979–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson GW, Page AJ, Cohen C, et al. Regional recurrence after negative sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmalbach CE, Nussenbaum B, Rees RS, Schwartz J, Johnson TM, Bradford CR. Reliability of sentinel lymph node mapping with biopsy for head and neck cutaneous melanoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(1):61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaveh AH, Seminara NM, Barnes MA, et al. Aberrant lymphatic drainage and risk for melanoma recurrence after negative sentinel node biopsy in middle-aged and older men. Head Neck. 2016;38 Suppl 1:E754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao C, Wong SL, Edwards MJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for head and neck melanomas. Ann Surg Oneal. 2003;10(1):21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson GW, Murray DR, Lyles RH, Hestley A, Cohen C. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in the management of cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Pfost Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(3):721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saltman BE, Ganly I, Patel SG, et al. Prognostic implication of sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Head Neck. 2010;32(12):1686–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez-Rivera F, Santillan A, McMurphey AB, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in patients with cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck: recurrence and survival study. Head Neck. 2008;30(10): 1284–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanks JE, Yalamanchi PY, Kovatch KJ, Ali SA, et al. Cranial Nerve Outcomes in Regionally Recurrent Head & Neck Melanoma After Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy. Podium Presentation, Triological Society Meeting. Coronado, CA2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. N Eng/J Med. 2017;376(23):2211–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. lancet Oneal. 2016;17(6):757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ml Ross. Counterpoint: Surgical Management of Lymph Node Basin in Sentinel Lymph NodePositive Melanoma. Oncology. 2016;30(10):891, 893–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarnaik AA, Zager JS, Sondak VK. Point: Surgical Management of Lymph Node Basin in Sentinel Lymph Node-Positive Melanoma. Oncology. 2016;30(10):891–892, 895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosko AJ, Vankoevering KK, Mclean SA, Johnson TM, Moyer JS. Contemporary Management of Early-Stage Melanoma: A Systematic Review. JAMA Facial Pfost Surg. 2017;19(3):232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oneal. 2001;19(16):3622–3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oneal. 2001;19(16):3635–3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cascinelli N An Overview on Sentinel Lymph Node Dissection. Paper presented at: 9th International Congress on Anti-Cancer Treatments; 1999, 1999; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evrard D, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(5):1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sperry SM, Charlton ME, Pagedar NA. Association of sentinel lymph node biopsy with survival for head and neck melanoma: survival analysis using the SEER database. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(12):1101–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrett BM, Kashani-Sabet M, Singer Ml, et al. Long-term prognosis and significance of the sentinel lymph node in head and neck melanoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(4):699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teltzrow T, Osinga J, Schwipper V. Reliability of sentinel lymph-node extirpation as a diagnostic method for malignant melanoma of the head and neck region. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36(6):481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Wilt JH, Thompson JF, Uren RF, et al. Correlation between preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and metastatic nodal disease sites in 362 patients with cutaneous melanomas of the head and neck. Ann Surg. 2004;239(4):544–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doting EH, de Vries M, Plukker JT, et al. Does sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous head and neck melanoma alter disease outcome? J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(7):564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly J, Fogarty K, Redmond HP. A definitive role for sentinel lymph node mapping with biopsy for cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Surgeon. 2009;7(6):336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shpitzer T, Segal K, Schachter J, et al. Sentinel node guided surgery for melanoma in the head and neck region. Melanoma Res. 2004;14(4):283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Ploeg AP, van Akkooi AC, Schmitz Pl, Koljenovic S, Verhoef C, Eggermont AM. EORTC Melanoma Group sentinel node protocol identifies high rate of submicrometastases according to Rotterdam Criteria. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(13):2414–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Essner R, et al. Validation of the accuracy of intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: a multicenter trial. Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial Group. Ann Surg. 1999;230(4):453– 463; discussion 463–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doting MH, Hoekstra HJ, Plukker JT, et al. Is sentinel node biopsy beneficial in melanoma patients? A report on 200 patients with cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28(6):673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fincher TR, McCarty TM, Fisher TL, et al. Patterns of recurrence after sentinel lymph node biopsy for cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2003;186(6):675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Estourgie SH, Nieweg OE, Valdes Olmos RA, Hoefnagel CA, Kroon BB. Review and evaluation of sentinel node procedures in 250 melanoma patients with a median follow-up of 6 years. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(6):681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vuylsteke RJ, van Leeuwen PA, Statius Muller MG, Gietema HA, Kragt DR, Meijer S. Clinical outcome of stage 1/11 melanoma patients after selective sentinel lymph node dissection: long-term follow-up results. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yee VS, Thompson JF, McKinnon JG, et al. Outcome in 846 cutaneous melanoma patients from a single center after a negative sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(6):429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leong SP, Kashani-Sabet M, Desmond RA, et al. Clinical significance of occult metastatic melanoma in sentinel lymph nodes and other high-risk factors based on long-term follow-up. World J Surg. 2005;29(6):683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nowecki ZI, Rutkowski P, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Ruka W. Survival analysis and clinicopathological factors associated with false-negative sentinel lymph node biopsy findings in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(12):1655–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cascinelli N, Bombardieri E, Bufalino R, et al. Sentinel and nonsentinel node status in stage IB and II melanoma patients: two-step prognostic indicators of survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4464–4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kettlewell S, Moyes C, Bray C, et al. Value of sentinel node status as a prognostic factor in melanoma: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;332(7555):1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corrigan MA, Coffey JC, O’Sullivan MJ, Fogarty KM, Redmond HP. Sentinel lymph node biopsy: is it possible to reduce false negative rates by excluding patients with nodular melanoma? Surgeon. 2006;4(3):153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emery RE, Stevens JS, Nance RW, Corless CL, Vetto JT. Sentinel node staging of primary melanoma by the “10% rule”: pathology and clinical outcomes. Am J Surg. 2007;193(5):618–622; discussion 622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riber-Hansen R, Abrahamsen HN, Sorensen BS, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Steiniche T. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR in sentinel lymph nodes from melanoma patients. Detection of melanocytic mRNA predicts disease-free survival. APMIS. 2008;116(3):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Testori A, De Salvo GL, Montesco MC, et al. Clinical considerations on sentinel node biopsy in melanoma from an Italian multicentric study on 1,313 patients (SOLISM-IMI). Ann Surg Oneal. 2009; 16(7):2018–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scoggins CR, Martin RC, Ross Ml, et al. Factors associated with false-negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oneal. 2010;17(3):709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veenstra HJ, Wouters MW, Kroon BB, Olmos RA, Nieweg OE. Less false-negative sentinel node procedures in melanoma patients with experience and proper collaboration. J Surg Oneal. 2011;104(5):454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Rosa N, Lyman GH, Silbermins D, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for head and neck melanoma: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(3):375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sabel MS, Griffith K, Sondak VK, et al. Predictors of nonsentinel lymph node positivity in patients with a positive sentinel node for melanoma. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2005;201(1):37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leung AM, Morton DL, Ozao-Choy J, et al. Staging of regional lymph nodes in melanoma: a case for including nonsentinel lymph node positivity in the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(9):879–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reintgen M, Murray L, Akman K, et al. Evidence for a better nodal staging system for melanoma: the clinical relevance of metastatic disease confined to the sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oneal. 2013;20(2):668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gyorki DE, Boyle JO, Ganly I, et al. Incidence and location of positive nonsentinel lymph nodes in head and neck melanoma. Eur J Surg Oneal. 2014;40(3):305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. lancet. 2018;392(10151):971–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kandel M, Allayous C, Dalle S, et al. Update of survival and cost of metastatic melanoma with new drugs: Estimations from the Mel Base cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2018;105:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polkowska M, Ekk-Cierniakowski P, Czepielewska E, Kozlowska-Wojciechowska M. Efficacy and safety of BRAF inhibitors and anti-CTLA4 antibody in melanoma patients-real-world data. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Smith MJF, Smith HG, Joshi K, et al. The impact of effective systemic therapies on surgery for stage IV melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carreau NA, Pavlick AC. Nivolumab and ipilimumab: immunotherapy for treatment of malignant melanoma. Future Oneal. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage Ill BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. New Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1813–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Prolonged Survival in Stage Ill Melanoma with lpilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. New Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage Ill Melanoma. New Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1789–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus lpilimumab in Resected Stage Ill or IV Melanoma. New Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doepker MP, Yamamoto M, Applebaum MA, et al. Comparison of Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography-Computed Tomography (SPECT/CT) and Conventional Planar Lymphoscintigraphy for Sentinel Node Localization in Patients with Cutaneous Malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(2):355–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trinh BB, Chapman BC, Gleisner A, et al. SPECT/CT Adds Distinct Lymph Node Basins and Influences Radiologic Findings and Surgical Approach for Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Head and Neck Melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(6):1716–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1b (Online Only). Survival and recurrence Kaplan-Meier curves by SLN status. X-axis: time (years), Y-Axis: Survival Probability. D) Local-RFS, E) Regional-RFS, F) Regional-RFS lacking confounding local, dermal-metastatic, and/or satellite recurrences, G) Distant-RFS. “-SLNB”=negative SLNB; “+SLNB”= positive SLNB