We read with great interest the prospective SARS-CoV-2 serosurveillance study of Harris et al. in your columns.1 During 6 months and before the UK vaccination campaign, they followed the antibody response in a cohort of 2246 healthcare workers (HCWs). They relied on 4 commercial kits and an in-house test to track the antibody response to natural SARS-CoV-2 exposure. As expected with kits that targets different proteins and total or specific immunoglobulin sub-groups, they observed, along time, fluctuating seropositivity from one test to another. Nevertheless, they showed that SARS-CoV-2 antibodies do not decline as quickly as predicted by smaller cohorts of patients with shorter follow-up.

With the start of worldwide vaccination campaigns, scattered evidence is emerging from the medical literature to dispute the second injection of mRNA vaccines in individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2.2 , 3 Knowing that a significant proportion of the population would be seropositive at the time of the first injection, we wanted to investigate the utility of a second dose under both supply and time constraints. Here we report our observations in a cohort of healthcare workers (HCWs) who were administered mRNA1273 at the inception of the national vaccination campaign. Manisty et al., first questioned the administration of the second dose of BNT162b2, another mRNA vaccine, so as to reserve it only for individuals not previously infected.3 They showed that the antibody response after a first dose in HCWs previously infected (n = 24) reached levels 140 times higher than their peak value before vaccination. Krammer et al. observed in previously infected individuals antibody titers 10–45 times higher than in their uninfected counterparts after a first-dose of either BNT162b2 (n = 88) or mRNA-1273 (n = 22) vaccines2.

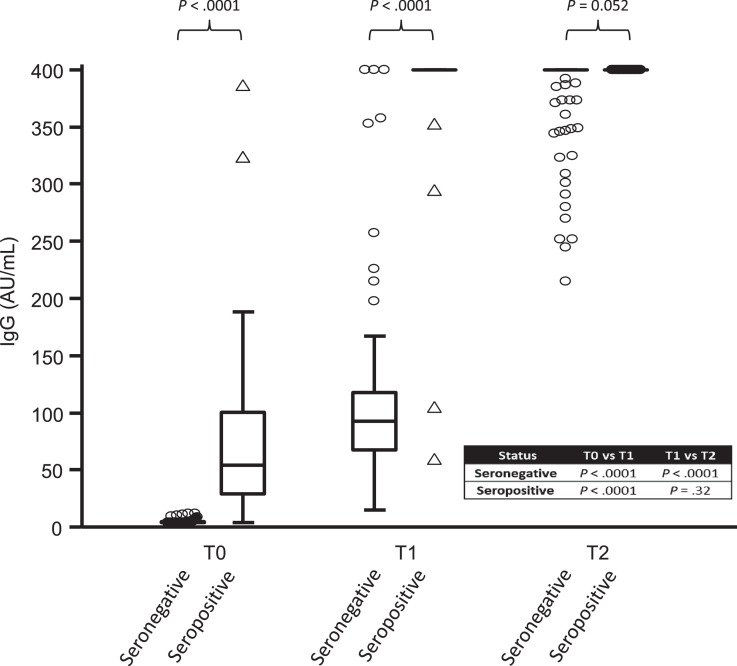

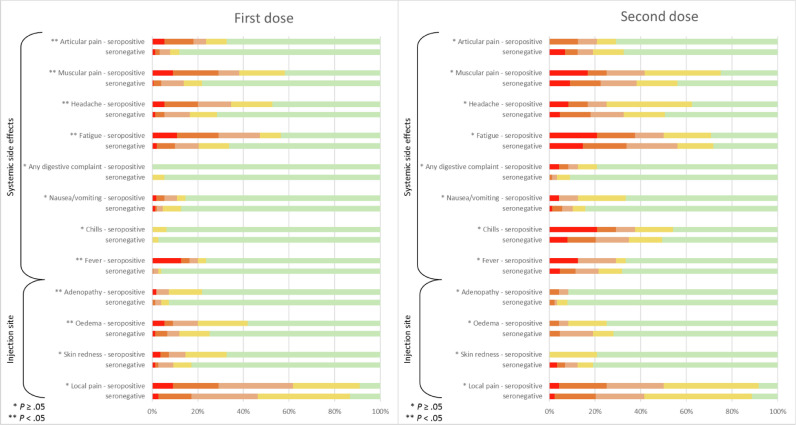

In our prospective study, we compared not only the antibody response (Fig. 1 ) but also the local and systemic side effects in terms of duration and intensity after the first and second dose of mRNA-1273 (Fig. 2 ).The quantitative analysis of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies directed against the subunits (S1) and (S2) of the virus spike protein was carried out using the LIAISON®SARS-CoV-2 IgG kit (DiaSorin®, Saluggia, Italy) on a LIAISON®XL analyzer previously validated in our laboratory.4 In order to assess the serological status of the participants (n = 160), a first dosage was carried out with a median time (± 95% confidence interval [CI]) of 2 (± 0.29) days before the first injection (T0). Among those, 36 participants were found to be seropositive. Two other samples were taken from all participants 2 weeks after the first injection (T1) (median time [± 95% CI]: 16 [± 0.25] days), and 2 weeks after the second injection (T2) (median time [± 95% CI]: 14 [± 0.21] days). Except for 2 individuals, all participants who were seropositive at T0, saw their antibody levels boosted by the first dose but no additional boosting effect was observed after the second injection. In these two individuals (1.6%), the second injection made it possible to raise their antibody levels from 59.7 and 105 AU/mL to above the maximum detection limit (> 400 AU/mL) at T2. In seronegative participants, the anti-S antibody titers obtained after a single dose were comparable to those obtained in unvaccinated seropositive participants while the second injection was necessary to achieve higher antibody levels approaching those obtained for seropositive individuals (T1). We also explored the frequency of side effects after the first dose in a slightly larger cohort (n = 206, mean age, 48.6 (± 11.6) years) including 151 seronegative (71% female) and 55 seropositive participants (69% female), as well as after the second dose in 113 participants (mean age, 49.2 (± 11.3) years) including 89 seronegative participants (69% female) and 24 seropositive participants (58% female). The intensity of local and systemic side effects reported by participants was graded into 4 levels of severity: (very mild, mild, moderate, severe). Common side effects such as articular pain, muscular pain, headache, fatigue, fever, adenopathy and oedema from the first dose appear to be more frequent and severe in previously infected individuals (P < .05). Nevertheless, it seems that the second injection generates a greater overall systemic reaction than that observed after the first one, regardless of the initial serological status of the participants. Seven days after the first or the second dose, all observed side effects disappeared in all participants and none were hospitalized. Two weeks after the last injection, a clinical follow-up questionnaire was sent to the 113 participants. Only 41 were returned at the time of redaction. None of the respondents reported thinking they had been infected. Ten of them had to undergo a RT-qPCR and all were negative.

Fig. 1.

Antibody responses to one and two doses of the mRNA-1273 in seronegative and seropositive individuals.

Fig. 2.

Reactogenicity and side effect profile of the mRNA-1273 in seronegative and seropositive individuals after the first and second doses.

Our results plead, in a supply-limited environment, for reserving the second dose scheme to seronegative individuals prior to vaccination, especially when the serological status is easily accessible, as the additional protective effect of the second dose has yet to be demonstrated in seropositive individuals. The determination of the antibody titers after the initial dose could be used in order to catch-up the very few vaccinees with a weaker response.

In the worrying context of an increase in the spread of mutant viruses around the world5 and given that most registered vaccine platforms use the two-dose-prime boost approach,6, 7, 8 this strategy would help speed up vaccination campaigns and achieve group immunization goals more rapidly. Even though titers of antibodies against S1 spike protein seem to correlate with viral neutralization studies,6 , 9 , 10 only long-term serosurveillance studies will not only confirm the results of our investigation but will also determine the IgG protection thresholds.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the HIS-IZZ (ethical agreement number: CEHIS/2021-7).

Authorship

Study concept and design: Marie Tré-Hardy, Roberto Cupaiolo, Emmanuelle Papleux, Alain Wilmet, Marc Vekemans, Ingrid Beukinga, Laurent Blairon. Investigation: All. Acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data and visualization: Marie Tré-Hardy, Roberto Cupaiolo, Laurent Blairon. Supervision and manuscript-first draft: Marie Tré-Hardy, Laurent Blairon. Critical revision of the manuscript: All.

Fig. 1 shows SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies titres directed against the subunits (S1) and (S2) of the virus spike protein before (T0), after the first (T1) and second injection (T2), according to the participant serological status (n = 160). The Box-and-Whisker plot represents the 25th and 75th percentiles. Inside the box, the horizontal line indicates the median (the 50th percentile). Discs and triangles respectively represent outside and far out values. A Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess the differences in IgG levels between seronegative and seropositive subjects on the one hand and to assess the changes in these levels between T0, T1 and T2 times within each of these groups on the other hand.

Fig. 2 lists the reported side-effects according to their nature and severity during the first (n = 206) and second (n = 113) dose administration. The gradation was as follow: absence (green), very mild (yellow), mild (light orange), moderate (dark orange), severe (red). A given participant possibly experienced more than one symptom. A Chi-square test was used for the comparison of side effects in seronegative versus seropositive subjects. A P-value < .05 was considered significant.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no relevant competing interest to disclose in relation to this work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the members of the clinical laboratory staff for technical assistance. We also thank the HCWs who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Harris RJ, Whitaker HJ, Andrews NJ, Aiano F, Amin-Chowdhury Z, Flood J. Serological surveillance of SARS-CoV-2: Six-month trends and antibody response in a cohort of public health workers. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krammer F, Srivastava K, Alshammary H, Amoako AA, Awawda MH, Beach KF. Antibody Responses in Seropositive Persons after a Single Dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2101667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manisty C, Otter AD, Treibel TA, McKnight Á, Altmann DM, Brooks T. Antibody response to first BNT162b2 dose in previously SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tré-Hardy M, Wilmet A, Beukinga I, Dogné JM, Douxfils J, Blairon L. Validation of a chemiluminescent assay for specific SARS-CoV-2 antibody. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(8):1357–1364. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Optimising the COVID-19 vaccination programme for maximum short-term impact. 2021.

- 6.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M. Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2427–2438. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voysey M, Costa Clemens SA, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh EE, Frenck RW, Falsey AR, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A. Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based Covid-19 Vaccine Candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prendecki M, Clarke C, Brown J, Cox A, Gleeson S, Guckian M. Effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection on humoral and T-cell responses to single-dose BNT162b2 vaccine. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00502-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]