Abstract

Introduction:

Suboptimal pathologic nodal staging prevails after curative-intent resection of lung cancer. We evaluated a lymph node specimen collection kit’s impact on lung cancer surgery outcomes in a prospective, population-based, staggered implementation study.

Methods:

From January 1, 2014 to August 28, 2018, we implemented the kit in three homogeneous institutional cohorts involving 11 eligible hospitals from four contiguous Hospital Referral Regions. Our primary outcome was pathologic nodal staging quality, defined by the following evidence-based measures: the number of lymph nodes or stations examined, proportions with poor-quality markers such as non-examination of lymph nodes, and aggregate quality benchmarks including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) criteria. Additional outcomes included perioperative complications, healthcare utilization, and overall survival.

Results:

Of 1492 participants, 56% had resection with the kit, 44% without. Pathologic nodal staging quality was significantly higher in the kit cases: 0.2% of kit cases versus 9.8% of non-kit cases had no lymph nodes examined; 3.2% versus 25.3% had no mediastinal lymph nodes; 75% versus 26% attained NCCN criteria (p<0.0001 for all comparisons). Kit cases showed no difference in perioperative complications or healthcare utilization except for significantly shorter duration of surgery, lower proportions with atelectasis, and slightly higher use of blood transfusion. Resection with the kit was associated with a lower hazard of death (crude, 0.78 [95% CI 0.61–0.99]; adjusted 0.85 [0.71 to 1.02]).

Conclusions:

Lung cancer surgery with a lymph node collection kit significantly improved pathologic nodal staging quality, with a trend towards survival improvement, without excessive perioperative morbidity or mortality.

Keywords: lymphadenectomy, surgical resection, quality of surgical care, nodal staging, lymph node specimen collection kit

Introduction

Surgical resection is the main curative treatment modality for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, aggregate 5-year overall survival only approximates 50%.1 Although pathologic nodal stage is a major prognostic factor,2 the quality of pathologic nodal staging of NSCLC predominantly falls below recommended standards.3–6 In an examination of lung resections from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, 12–18% of resections examined no lymph nodes (‘pathologic [p] NX’);4 40–50% examined no mediastinal nodes.5 Only 8% of NSCLC resections in a US metropolitan region met National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-recommended quality.6 Most failed to examine lymph nodes from the hilum and at least three mediastinal stations.

Suboptimal pathologic nodal staging is a universal problem. 3,7–9 The universal nature of this pathologic nodal staging quality gap has led to policy changes, including evolution in the characterization of good-quality surgery. The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (ACS-CoC) revised the definition of good-quality curative-intent lung cancer surgery in 2020 to require inclusion of a minimum of three named and/or numbered anatomic lymph node stations as well as at least one named and/or numbered hilar or intrapulmonary lymph nodes.10 Additionally, The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) has proposed re-categorizing the residual disease (‘R-factor’) classification after surgical resection for lung cancer for the 9th edition of the lung cancer staging system due in 2025 by including a new sub-category of ‘R-uncertain’ resections in which the completeness of surgery cannot be reliably determined.11 These ‘R-uncertain’ resections have inferior overall survival. Inadequate nodal staging is the most prevalent cause of the uncertainty about residual disease after curative-intent NSCLC surgery.11

In pilot studies, a pre-labeled lymph node specimen collection kit improved the quality of pathologic nodal staging of NSCLC.12 We hypothesized that adoption of the kit by a diverse group of surgeons and institutions would improve the population-level quality of lung cancer resection. We conducted a pragmatic population-based implementation study, and report the kit’s effect on pathologic staging, perioperative complications, healthcare utilization, and overall survival.

Materials and Methods

Intervention

The lymph node collection kit contains the IASLC lymph node map and specimen jars labeled for each of the hilar and mediastinal stations.13 Specific containers are marked to indicate stations mandated for examination: stations 2R,4R,7,8,9 and 10R for right-sided tumors; 4L,5,6,7,8,9 and 10L for left-sided tumors (see Supplementary Table 1 for anatomic nomenclature).14 The kit includes a checklist to explain why specimens were not collected from mandatory stations.12

Setting

With Institutional Review Board approval, including a waiver of the informed consent requirement for this low-risk quality improvement study, we deployed the kit for routine use in all eligible hospitals within four contiguous Hospital Referral Regions: Jonesboro, Arkansas; Oxford and Tupelo, Mississippi; and Memphis, Tennessee. Hospital Referral Regions are geographic units developed by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care to delineate regional US healthcare markets.15 Each is a self-contained healthcare population unit with minimal leakage of care. Eligible hospitals had a minimum of five annual curative-intent lung cancer resections. They ranged from high-volume metropolitan hospitals to low-volume rural community hospitals. This population-based Mid-South Quality of Surgical Resection (MS-QSR) cohort includes >95% of lung cancer resections in the catchment area.

Study population

All patients who underwent curative-intent surgery for lung cancer at participating institutions are in the MS-QSR database. Trained data managers directly abstracted information from Electronic Health Records. For this analysis, we excluded recipients of neo-adjuvant therapy and previous lung cancer resection due to potential confounding of their lymph node evaluation.

Study design

We conducted a multiple baseline, staggered implementation study. This scientifically rigorous pragmatic alternative to cluster randomization allows for a population-based approach across a defined geographic region with high external validity and estimation of ‘real-world’ effectiveness.16,17 First, we retrospectively abstracted information on all NSCLC resections performed from 2009 to 2013 at each eligible institution, to establish baseline volume and quality performance characteristics. We then assigned eligible institutions into three homogeneous cohorts based on their annual case volume, teaching status, and location in an urban or rural area, to determine the prospective implementation sequence (Supplementary Table 2).

At pre-specified intervals based on cohort assignment, we conducted workshops involving senior hospital administrators, surgeons, pathologists, and cardiovascular operating room nursing staff during which we discussed the institution-specific pathologic nodal staging quality gap and its adverse survival impact. We trained staff to use the kit, without initially providing it. Cases performed before institutional activation of kit use provided a prospective pre-implementation baseline cohort. Upon institution-wide activation, we encouraged use of the kit by all surgeons accredited to perform lung cancer resections, for all lung cancer resections at that institution (post-implementation cohort). In this ‘real-world’ dissemination and implementation study, adoption of the kit was not uniform across institutions and surgeons. We identified resections in the post-implementation phase which used and did not use the kit, for additional sub-set analyses. We maintained a lean inventory of kits to avoid spillover into institutions still in the pre-implementation phase. We prospectively collected data for all resections performed from January 1, 2014 onwards, irrespective of kit usage.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the quality of pathologic nodal staging. Because there is no universally-accepted definition of good-quality pathologic nodal staging, we examined multiple survival-associated benchmarks, including: the number of examined lymph nodes and anatomic stations;18 the frequency of poor-quality markers such as pNX and non-examination of mediastinal lymph nodes;4,5 and the frequency of meeting recommended quality benchmarks, including criteria recommended by the NCCN,19 the ACS-CoC,20 the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC),21 and ‘systematic sampling’ as defined in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0030 trial (Supplementary Table 3 for details).14 Other outcomes included the frequency of perioperative complications, healthcare service utilization, Intensive Care Unit and hospital admission, and overall survival. Information on death was updated every six months from each institution’s Tumor Registry. All patients alive were censored on February 29, 2020. The MS-QSR does not currently include information on cause-specific mortality.

Sample size and power

We defined the study period to ensure that all implementation cohorts would have a minimum of nine months to ramp up adoption and six months to measure sustainability of the intervention. A priori sample size justification for effectiveness endpoints, based on numbers of examined lymph nodes, indicated that 350–500 patients would provide 80–90% power to detect an increased median number of lymph nodes examined from 5 in non-kit surgery to 12 in kit surgery, and an increase in the percentage of patients with examined mediastinal lymph nodes from 27% in non-kit surgery to 94% in kit surgery, in our primary outcomes analysis, with a 5% type-I error rate under a range of scenarios (Supplementary Methods).12

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are summarized with median (interquartile range [IQR]) and compared with the two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables are presented as frequency (percent) and compared with the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or logistic regression. We modeled lymph node count variables with univariate and multiple variable Poisson regression models and present Incidence Rate Ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We estimated overall survival with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between groups using the log-rank test. We fit univariate and multiple variable Cox proportional hazards models for survival (assuring each model had >10 events per covariate) and examined the proportional hazards assumption graphically using log(-log) plots.22,23 The primary exposure variable for all analyses is kit use (‘yes’ versus ‘no’). Hazard ratios (HR) are reported with 95% CI. In primary analyses, proportional hazards models account for the intra-cluster dependence of operating surgeon using a robust sandwich covariance estimator.24

We fit multiple variable Poisson and proportional hazards models adjusting for all measured potential confounders that were not on the causal pathway between the exposure and outcome, including: time since study initiation (evaluated continuously in quarter years), age at surgery, race, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score as a marker of patient frailty, tumor size, M-category, sex, histology, extent of resection, pathologic grade, number of comorbidities, preoperative staging with positron emission tomography-computer tomography (PET-CT) scan, pre-operative invasive staging, and pathology group (full model). We also constructed a parsimonious proportional hazards model that iteratively removed potential confounders that did not change the hazard ratio for the primary exposure variable by more than 10%.

Sensitivity analyses excluded subjects with one of the following: sub-lobar resections, death within 60 days after surgery, or resection by non-implementing surgeons (surgeons who never used the kit). We also conducted a secondary analysis including use of adjuvant therapy in the model. We excluded this from the primary analysis because of its likely presence on the causal pathway between the exposure and overall survival. Finally, we conducted a propensity analysis, matching for the above-mentioned variables and time. Approximately 10–30% of patients were missing pulmonary function data, we report the percent unknown by group and treated them as normal in the statistical adjustment (and as abnormal in sensitivity analyses). Other missing data elements were less than 5% of the total sample size, therefore complete-case analysis was conducted.25 P-values are two-tailed, and considered statistically significant when <0.05. We follow the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.26 Analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC) or R (3.5.3).

Results

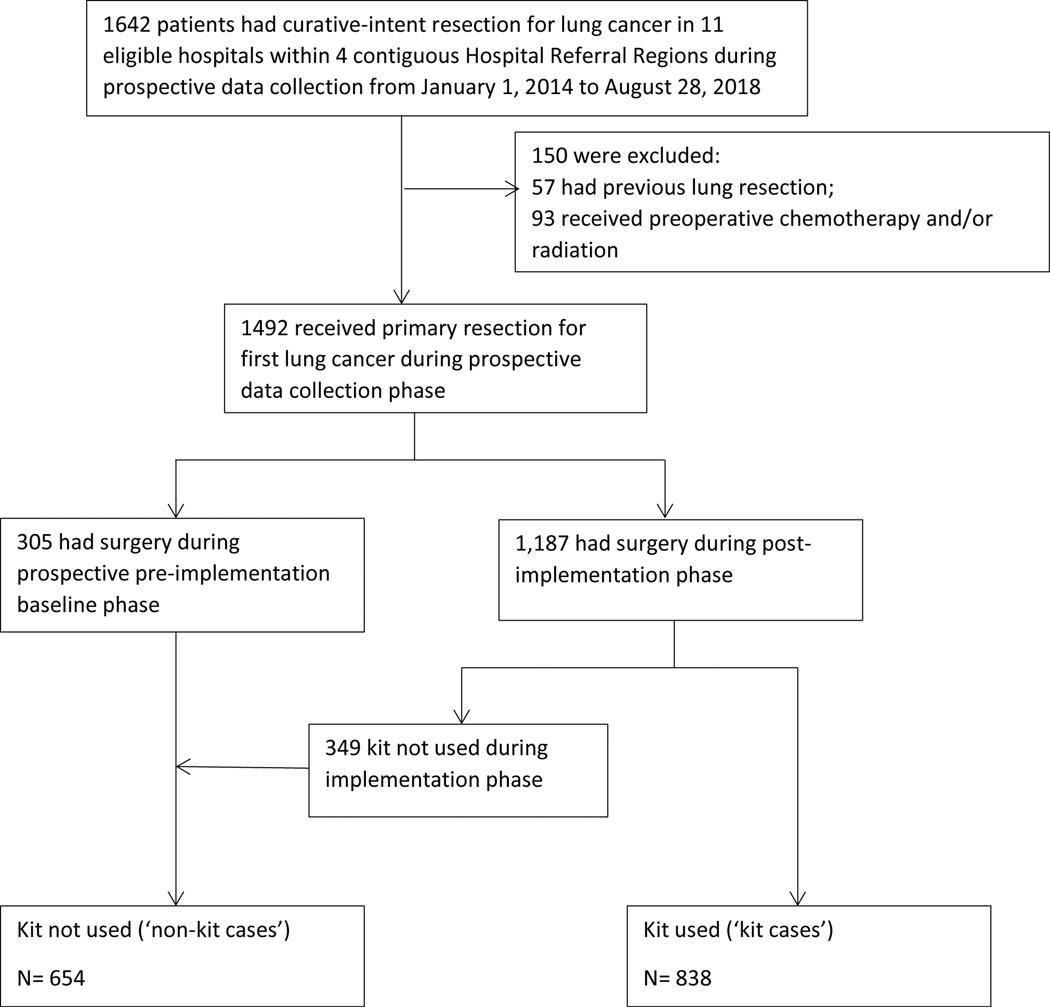

From January 1, 2014 to August 28, 2018, a total of 1642 patients underwent curative-intent surgical resection across 11 hospitals. After exclusions, 305 patients had surgery during the pre-implementation phase and 1187 had surgery during the post-implementation phase, of which 838 were performed with the kit and 349 without (Figure 1). All resections were performed by 35 board-certified cardiothoracic surgeons, including 787 (53%) by seven general thoracic surgeons, except for 114 resections (8%) performed by two general surgeons. The kit was used at least once by 24 ‘implementing’ surgeons.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. Selection and distribution of analytic cohort.

Study Population

Proportionately, fewer Black patients (18% versus 25%) and men (49% versus 56%) had surgery with the kit. There were differences in the distribution of age, ASA score, histology, tumor size, pathologic tumor grade, use of pre-operative PET-CT, invasive staging tests, and extent of resection (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). However, the number of comorbidities, insurance status, pulmonary function, and aggregate clinical stage were similar. Although the pathologic T-category distribution was similar, the pathologic N-category was skewed towards higher distribution in resections with the kit.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of patients who had surgical resection with a lymph node specimen collection kit (‘kit used’) and those who did not (‘kit not used’).*

| Characteristic | Kit used† (N=838) | Kit not used† (N=654) | Total (N=1492) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age - Mean (SD) | 68.0 (8.8) | 67.0 (9.0) | 67.5 (8.9) |

| Tumor Size - Mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.9 (1.8) |

| Race | |||

| White | 678 (80.9) | 483 (73.9) | 1161 |

| Black | 148 (17.7) | 165 (25.2) | 313 |

| Asian | 5 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) | 8 |

| Other/not reported | 7 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 10 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 406 (48.5) | 364 (55.7) | 770 |

| Female | 432 (51.6) | 290 (44.3) | 722 |

| Insurance | |||

| Medicare | 357 (42.6) | 262 (40.1) | 619 |

| Medicaid | 142 (17.0) | 99 (15.1) | 241 |

| Commercial | 317 (37.8) | 269 (41.1) | 586 |

| Self-Insured/N one | 22 (2.6) | 24 (3.7) | 46 |

| Extent of Resection | |||

| Pneumonectomy | 19 (2.3) | 30 (4.6) | 49 |

| Bi-lobectomy | 33 (3.9) | 16 (2.5) | 49 |

| Lobectomy | 737 (88.0) | 462 (70.6) | 1199 |

| Segmentectomy | 24 (2.9) | 56 (8.6) | 80 |

| Wedge | 25 (3.0) | 90 (13.8) | 115 |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 479 (57.2) | 340 (52.0) | 819 |

| Squamous | 271 (32.3) | 219 (33.5) | 490 |

| Adenosquamous | 17 (2.0) | 15 (2.3) | 32 |

| Large Cell | 9 (1.1) | 19 (2.9) | 28 |

| Other | 62 (7.4) | 61 (9.3) | 123 |

| Pathologic Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 112 (13.4) | 105 (16.1) | 217 |

| Moderately | 362 (43.2) | 245 (37.5) | 607 |

| Poorly | 253 (30.2) | 199 (30.4) | 452 |

| Undifferentiated | 30 (3.6) | 13 (2.0) | 43 |

| Not Reported | 81 (9.7) | 92 (14.1) | 173 |

| Number of Comorbidities | |||

| 0 | 165 (19.7) | 147 (22.5) | 312 |

| 1 | 311 (37.1) | 261 (39.9) | 572 |

| 2 | 213 (25.4) | 146 (22.3) | 359 |

| 3 | 107 (12.8) | 63 (9.6) | 170 |

| ≥4 | 42 (5.0) | 37 (5.7) | 79 |

| PET-CT | |||

| No | 99 (11.8) | 108 (16.5) | 207 |

| Yes | 739 (88.2) | 546 (83.5) | 1285 |

| Invasive Staging | |||

| No | 571 (68.1) | 506 (77.4) | 1077 |

| Yes | 267 (31.9) | 148 (22.6) | 415 |

| Diffusion Capacity for Carbon Monoxide | |||

| <60 | 162 (19.3) | 116 (17.7) | 278 |

| >=60 | 381 (45.5) | 299 (45.7) | 680 |

| Unknown | 295 (35.2) | 239 (36.5) | 534 |

| Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second | |||

| < 1 Liter | 20 (2.4) | 10 (1.5) | 30 |

| >= 1 Liter | 737 (88.0) | 505 (77.2) | 1242 |

| Unknown | 81 (9.7) | 139 (21.2) | 220 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Score | |||

| 1 | 29 (3.5) | 32 (4.9) | 61 |

| 2 | 693 (82.7) | 471 (72.0) | 1164 |

| 3 | 92 (11.0) | 79 (12.1) | 171 |

| 4 | 24 (2.9) | 72 (11.0) | 96 |

| Clinical T-Category | |||

| cT1 | 493 (58.8) | 404 (61.8) | 897 |

| cT2 | 198 (23.6) | 124 (18.9) | 322 |

| cT3 | 84 (10.0) | 59 (9.0) | 143 |

| cT4 | 48 (5.7) | 39 (6.0) | 87 |

| cTx | 15 (1.8) | 28 (4.3) | 43 |

| Clinical N-Category | |||

| cN0 | 776 (92.6) | 603 (92.2) | 1379 |

| cN1 | 37 (4.4) | 30 (4.6) | 67 |

| cN2 | 21 (2.5) | 20 (3.1) | 41 |

| cN3 | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 5 |

| Clinical M-Category | |||

| cM0 | 768 (91.7) | 600 (91.7) | 1368 |

| cM1 | 70 (8.4) | 54 (8.3) | 124 |

| Aggregate Clinical Stage | |||

| I | 546 (65.2) | 419 (64.1) | 965 |

| II | 198 (23.6) | 169 (25.8) | 367 |

| III | 74 (8.8) | 58 (8.9) | 132 |

| IV | 12 (1.4) | 5 (0.8) | 17 |

| Not reported | 8 (1.0) | 3 (0.5) | 11 |

| Pathologic T-Category | |||

| pT1 | 406 (48.5) | 323 (49.3) | 729 |

| pT2 | 285 (34.0) | 194 (29.7) | 479 |

| pT3 | 109 (13.0) | 92 (14.1) | 201 |

| pT4 | 35 (4.2) | 39 (6.0) | 74 |

| pTx | 3 (0.4) | 6 (0.9) | 9 |

| Pathologic N-Category | |||

| pNX | 2 (0.2) | 64 (9.8) | 66 |

| pN0 | 678 (80.9) | 475 (72.6) | 1153 |

| pN1 | 87 (10.4) | 70 (10.7) | 157 |

| pN2 | 71 (8.5) | 45 (6.9) | 116 |

| Pathologic M-Category | |||

| pM0 | 828 (98.8) | 644 (98.5) | 1472 |

| pM1 | 10 (1.2) | 10 (1.5) | 20 |

| Aggregate Pathologic Stage | |||

| I | 533 (63.6) | 406 (62.1) | 939 |

| II | 175 (20.9) | 136 (20.8) | 311 |

| III | 116 (13.8) | 87 (13.3) | 203 |

| IV | 10 (1.2) | 10 (1.5) | 20 |

| Not reported | 4 (0.5) | 15 (2.3) | 19 |

| Adjuvant Therapy Use | |||

| Yes | 201 (24.0) | 93 (14.2) | 294 |

| No | 637 (76.0) | 561 (85.8) | 1198 |

Cases in which the kit was not used include all pre-implementation and some post-implementation operations performed as adoption of the kit intervention evolved over time.

Number (percentage) unless otherwise stated.

PET-CT= positron emission tomography-computer tomography; SD= standard deviation.

Quality of pathologic nodal staging

We used three approaches to evaluate pathologic nodal staging: the number of lymph nodes and nodal stations examined; proportions with poor-quality extremes; and the proportions attaining recommended nodal staging quality criteria. Use of the kit was associated with examination of significantly more lymph nodes and nodal stations, with a median of 13 (IQR 8–18) lymph nodes examined from all stations in kit cases versus 9 (3–15) in non-kit cases; 6 (4–8) mediastinal lymph nodes versus 3 (0–6); 4 (3–5) mediastinal nodal stations versus 2 (0–3); 6 (5–7) total nodal stations versus 4 (2–5); (p<0 0001 in all comparisons, Table 2). These associations remained statistically significant in fully adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference in the number of mediastinal lymph nodes (p=0.40) or stations (p=0.64) examined among the non-kit cases between the pre- and post-implementation cohorts (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2.

Comparison of thoroughness of nodal examination between patients who had surgical resection with a lymph node specimen collection kit (‘kit used’) and those who did not (‘kit not used’).

| Nodal Examination | Kit used (N=838) | Kit not used (N=654) | P-Value | Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% Confidence Limits | P-Value | |||||

| All lymph node stations† | 6 (5, 7) | 4 (2, 5) | <0.0001 | 1.63 | 1.52 | 1.75 | <0.0001 |

| Mediastinal lymph node stations† | 4 (3, 5) | 2 (0, 3) | <0.0001 | 2.10 | 1.91 | 2.31 | <0.0001 |

| All lymph nodes† | 13 (8, 18) | 9 (3,15) | <0.0001 | 1.41 | 1.35 | 1.47 | <0.0001 |

| Hilar/intrapulmonary lymph nodes† | 6 (3, 10) | 4 (1, 9) | <0.0001 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.196 | <0.0001 |

| Mediastinal lymph nodes† | 6 (4, 8) | 3 (0, 6) | <0.0001 | 1.89 | 1.77 | 2.02 | <0.0001 |

Median (IQR (interquartile range defined as: Lower Quartile, Upper Quartile))

Adjusted for time, age, race, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, American Society of Anesthesiology score, tumor size, M-category, sex, histology, extent of resection, pathologic grade, number of comorbidities, preoperative staging with positron emission tomography-computer tomography scan, pre-operative invasive staging, and pathology group.

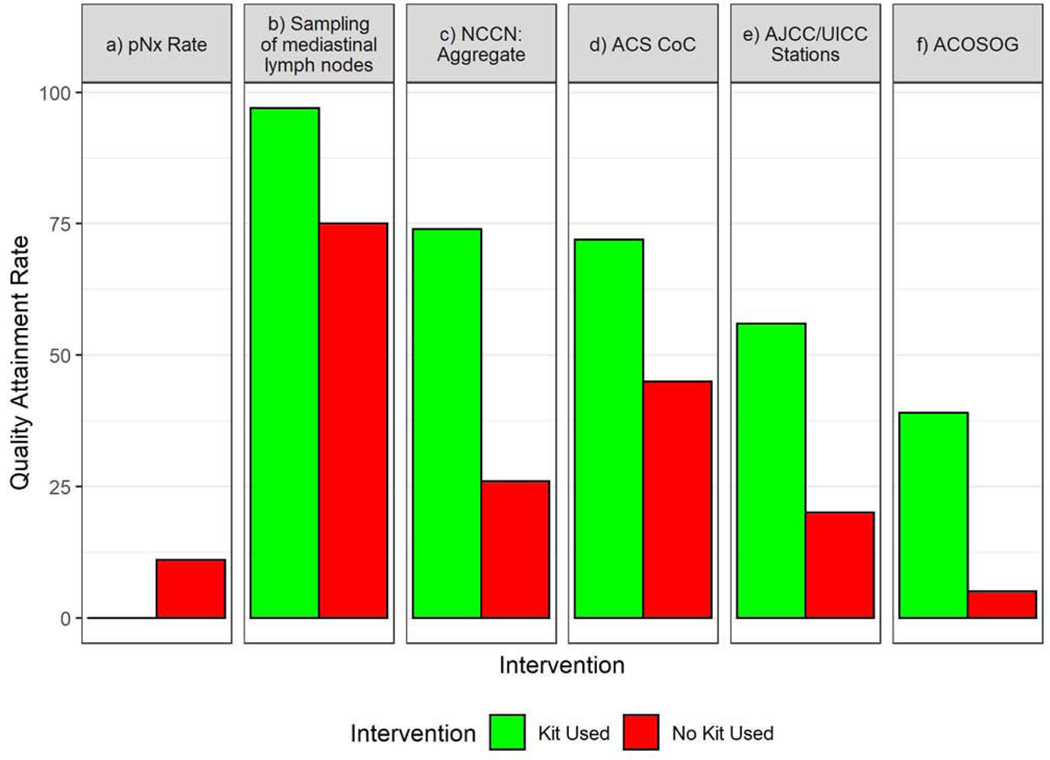

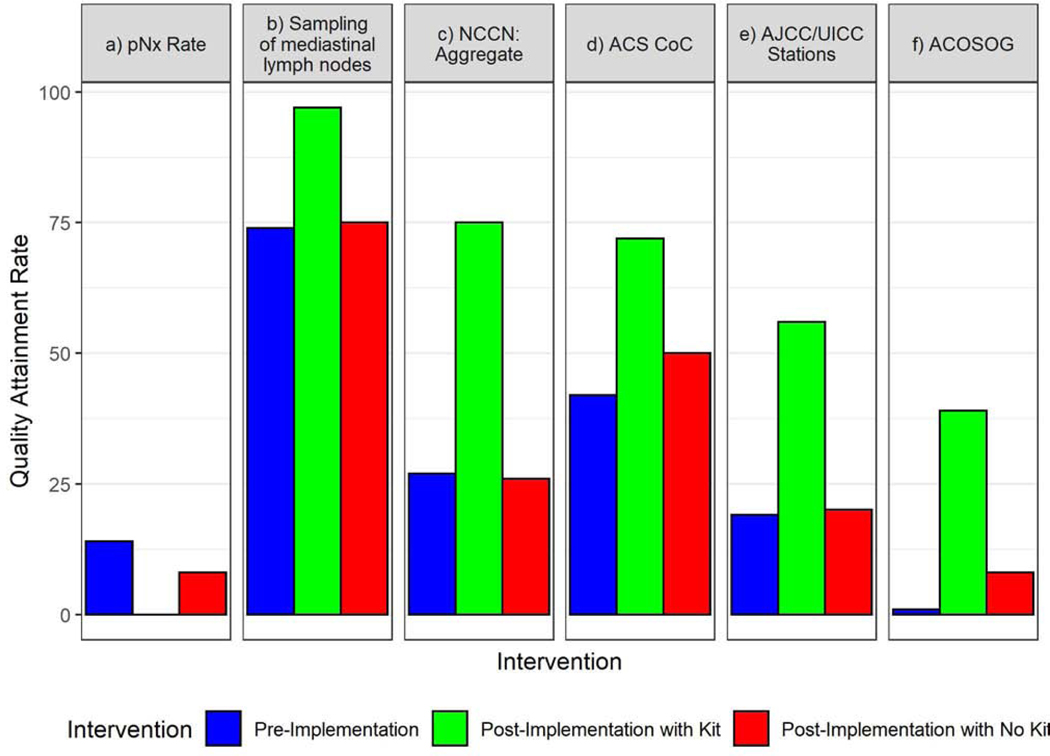

When the kit was used, the proportion with pNX (0.2% versus 9.8%, p<0.0001) and un-examined mediastinal lymph nodes (3.2% versus 25.3%, p<0.0001) diminished significantly compared to non-kit cases (Fig 2–A). The proportion attaining good-quality benchmarks recommended by the NCCN (74.5% versus 26.4%, p<0.0001), the ACS-CoC (72.3% versus 45.4%, p<0.0001), the AJCC (56.1% versus 19.7%, p<0.0001), and ACOSOG (39.3% versus 5.0%, p<0.0001) were significantly higher when the kit was used (Fig 2–A, Supplementary Table 6). Non-kit cases, before or after implementation, were significantly less likely to achieve quality benchmarks than kit cases (Fig 2–B). Quality attainment in non-kit cases was similar between pre- and post-implementation periods, with the exception of pNX and the ACOSOG criteria, which were better in post- versus pre- implementation non-kit cases (Figure 2–B). Examination of at least three mediastinal nodal stations, the most frequently deficient component of the NCCN quality standard, was achieved in only 29% of non-kit cases, compared to 80% of kit cases; hilar or intrapulmonary lymph nodes were examined in 83% of non-kit cases versus 97% of kit cases (p<0.0001, Figure 3, Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 2.

Frequency of attainment of six specific markers of pathologic nodal staging quality. A.) Kit (green bars) versus non-kit cases (red bars); B.) Pre-implementation cases (blue bars) versus post-implementation kit cases (green bars) versus post-implementation non-kit cases (red bars). pNX= no lymph nodes examined in resection specimen; NCCN= National Comprehensive Cancer Network (criteria require the combination of anatomic resection, negative resection margins, examination of at least one hilar and/or intrapulmonary lymph node and three mediastinal lymph node stations); ACS-CoC= American College of surgeons Commission on Cancer (criteria require examination of a minimum of ten lymph nodes in resections for pathologic stage I and II lung cancer); AJCC/UICC= American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control (criteria require examination of three lymph nodes from hilar and/or intrapulmonary stations and three mediastinal nodal stations and a minimum of six lymph nodes); ACOSOG= American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (systematic lymph node sampling criteria require examination of lymph nodes from stations 2R,4R, 7 and 10R during resection of right-side tumors and examination of stations 4L,5,6,7 and 10L during resection of left-side tumors). *Bars indicate statistically significant differences at the p<0.05 level.

Figure 3.

Attainment of the four components of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) surgical quality recommendations: anatomic resection, negative resection margins, examination of at least one hilar and/or intrapulmonary lymph node and three mediastinal lymph node stations.

Perioperative complications, healthcare utilization, postoperative mortality

The median duration of surgery was 123 (IQR 89–178) minutes in kit cases, versus 144 (109–188) minutes in non-kit cases (p<0.0001). The duration of surgery decreased sequentially over time for kit cases, but not for non-kit cases (Supplementary Figure 1). Blood transfusions were used in 8% of kit cases, compared to 5% of non-kit cases (p=0.017). Other than a lower proportion of kit cases with atelectasis, there was no significant difference in perioperative complications, such as cardiac arrhythmias, chylothorax, or wound infection, between the cohorts (Supplementary Table 8). Healthcare utilization was similar or lower in the kit cases: duration of chest tube drainage was 3 days (2–6) in the kit cases versus 4 days (2–6) in the non-kit cases (p<0.0001); the length of stay in the Intensive Care Unit was 1 day (1–2) versus 2 days (1–3) (p=0.0002); and hospital length of stay was 5 days (3–7) versus 5 days (3–8). There was no significant difference in the frequency of hospital readmission within 60 days, or death within 30, 60, or 90 days (Supplementary Table 8).

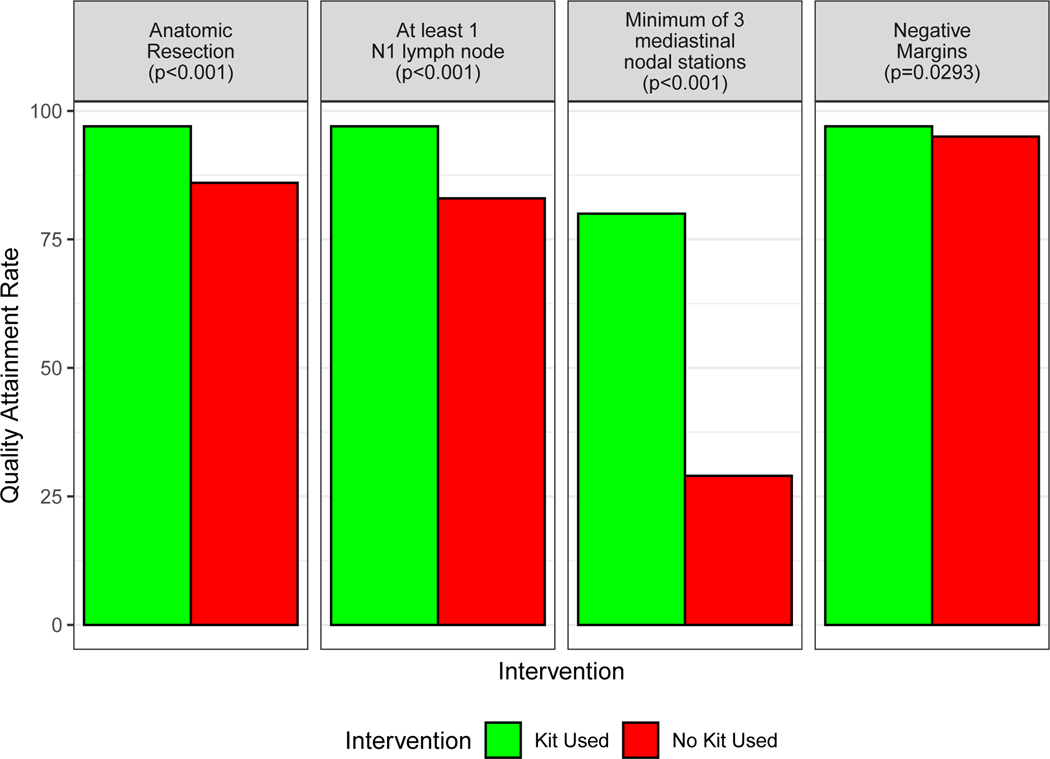

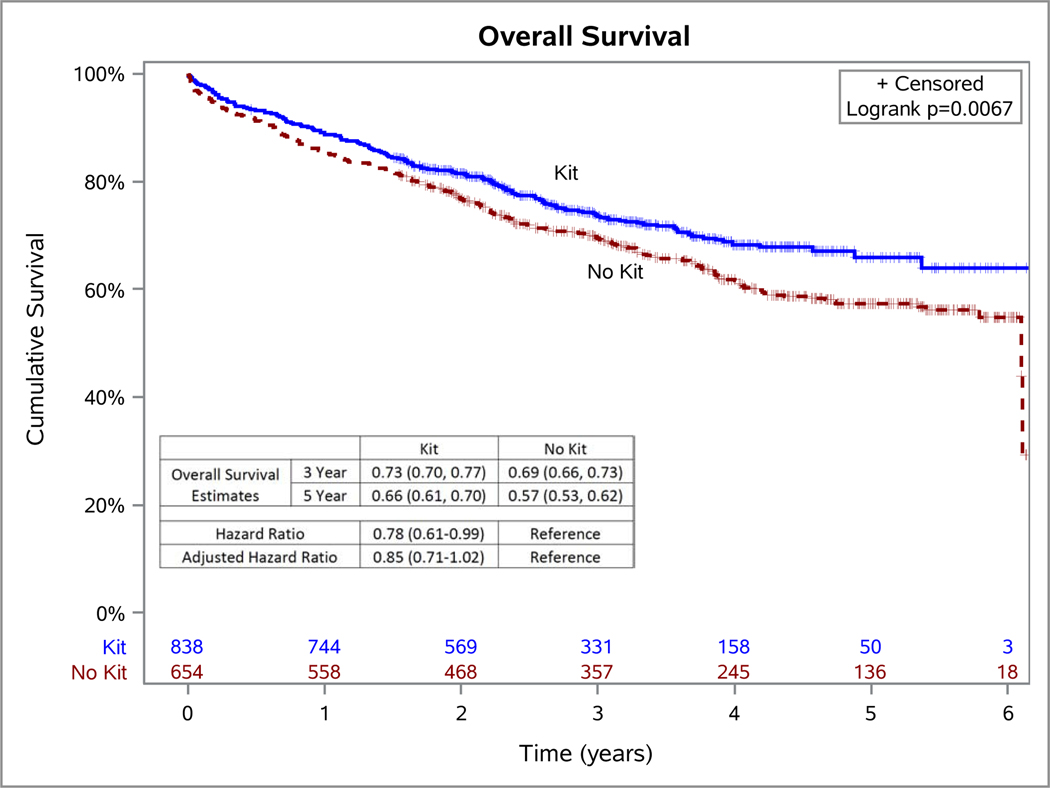

Survival

Patients had a median of 34 months of follow-up (IQR 22–49) in the whole cohort: 38 months (22–57) in the non-kit cases and 32 months (21–45) in the kit cases. Patients who had resection with the kit had a crude hazard ratio of 0.78 (95% CI 0.61–0.99; p=0.04; Figure 4) compared to those whose surgery was done without the kit. After adjusting for all potential confounders, patients who had resection with the kit had an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% CI 0.71–1.02; p=0.0716; Supplementary Table 9). Attainment of NCCN criteria was associated with significantly better survival in this cohort (p=0.0125, Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of patients who had surgery with and without a lymph node specimen collection kit. HR=Hazard Ratio; aHR= Hazard ratio adjusted for time since study initiation (evaluated continuously in quarter years), age at surgery, race, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score as a marker of patient frailty, tumor size, M-category, sex, histology, extent of resection, pathologic grade, number of comorbidities, preoperative staging with positron emission tomography-computer tomography (PET-CT) scan, pre-operative invasive staging, and pathology group

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis of overall survival evaluated the impact of surgery with the kit in several fully adjusted models: limited to implementing surgeons (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.69–0.94; p=0.0060, N=1261), excluding those who died within 60 days of surgery (HR 0.94; 95%CI 0.77–1.14; p=0.5077, N=1437), and excluding sub-lobar resections (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.70–1.02; p=0.0788, N=1377). Additional analyses of overall survival included a fully adjusted model that also controlled for the use of adjuvant therapy (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.70–1.01; p=0.0606) which was used in 24% of kit cases versus 14% of non-kit cases (p<0.0001). In a parsimonious model adjusting for a reduced set of covariates (pathology group and time), HR was 0.81 (95% CI 0.63–1.03; p=0.0881, Supplementary Table 9). When subjects with missing pulmonary function tests were re-classified as abnormal, results from the fully adjusted model remained consistent (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.71–1.01, p=0.0624). Finally, a propensity score matched analysis of 442 resections with the kit versus 442 without (Supplementary Table 10), yielded an HR of 0.84 (95% CI 0.63–1.12; p=0.2233).

Discussion

Poor-quality pathologic nodal staging is associated with worse perioperative outcomes and worse-than-expected survival among patients with early-stage NSCLC.27, 28 We found that surgery with a lymph node specimen collection kit in a population-based cohort improved the odds of attaining survival-impactful surgical resection quality benchmarks, and was associated with a reduced hazard of death without increasing perioperative morbidity, mortality, or utilization of healthcare resources.

Underlying the kit intervention is a ‘chain of responsibility’ conceptual model, which recognizes good-quality staging practice as an outcome requiring optimal interaction between interdependent teams from the time of surgery to the publication of the final pathology report. The key agents are the surgeon, operating room team, specimen transporters, pathology technicians, and pathologist. The model acknowledges the need for sequential hand-offs across these teams and the potential for failed hand-offs to impair the overall achievement of quality nodal dissection.29 We designed the kit to help surgery teams heighten awareness of the need to retrieve and correctly label lymph nodes from recommended anatomic locations using standardized nomenclature, reduce the risk of specimen loss in transit, and increase the likelihood of thorough examination and accurate reporting by the pathology team. In pilot studies, the kit improved the concordance between surgeons and pathologists in identifying the lymphadenectomy procedure performed.30

We conducted this implementation study after discovering a wide, survival-impactful gap between the recommended quality of pathologic nodal staging and actual clinical practice.3–6 Others have since demonstrated the near-universality of this gap.7–9 The ACS-CoC adopted the lymph node component of the NCCN benchmark as the quality standard for accredited institutions from 2020 onward.10 Use of the kit significantly improved the odds of attaining this standard of quality along with other important, evidence-based benchmarks. Quality was generally similar between pre- and post-implementation non-kit cases. This suggests that improvements are mostly attributable to the kit, while heightened awareness, presumed in post-implementation non-kit cases, failed to provide similar impact.

In addition to quality improvements, the kit also showed evidence of being safe and efficient. Resections with the kit were not only associated with decreased surgical and hospital stays, but the kit also did not lead to increases in any perioperative complications, postoperative mortality, or utilization of healthcare resources, with the exception of blood transfusions. The reduction in surgery time in the kit cohort was unexpected and seems paradoxical. Feedback from surgeons suggests that routine use of the kit induces greater intraoperative efficiency during the lymphadenectomy procedure. The greater use of blood transfusions is probably as expected, given the greater thoroughness of mediastinal lymphadenectomy when the kit was used.

The absence of randomization opens the possibility for bias to account for outcome differences. For example, surgeons who used the kit may have been more proficient; however, analysis restricted to implementing surgeons revealed results consistent with the overall study population. The kit also may have been preferentially used in healthier patients. Although we did not record reasons why the kit was not used, we encouraged (but could not enforce) use of the kit for all post-implementation resections. More of the non-kit cohort had sub-lobar resections, which might indicate greater frailty as a competing cause of increased mortality, therefore, we adjusted our analyses for ASA score and pulmonary function. However, these sub-lobar resections might also indicate a greater prevalence of patients with lower-risk radiologic lesions, which would tend to have the opposite effect. Additionally, the sensitivity analysis eliminating patients with sub-lobar resection revealed results similar to the full cohort. Furthermore, guidelines recommend the same standard of pathologic nodal staging for patients who have sub-lobar resection.10,19–21

Accurate pathologic nodal staging may have simply improved the categorization of patients into risk strata, without necessarily changing actual outcomes (the ‘Will Rogers phenomenon’).31 But this purely statistical phenomenon, which causes spurious improvement in stage-stratified survival because of differences in the thoroughness of application of staging tests, would not explain the non-stage-stratified survival improvement. Improved nodal evaluation may not itself directly improve survival, but might be linked to another action, such as adjuvant therapy. More patients in the kit cohort received adjuvant therapy, however, adjustment for adjuvant therapy only slightly attenuated the hazard ratio. Finally, we hypothesize that more thorough nodal evaluation in theory may also eliminate occult oligo-metastatic nodal disease, which otherwise might have been left behind, causing a type of incomplete resection.11,32 Supporting this hypothesis, the kit was particularly effective in eliminating the extremes of poor pathologic nodal staging such as pNX and non-examination of mediastinal lymph nodes, which are most likely to be associated with inadvertent incompleteness of resection (extremes of the proposal IASLC R-uncertain category).32

Although effective in overcoming extremes of poor pathologic nodal staging and stimulating achievement of greater levels of systematic sampling, the kit may not encourage surgeons to perform en-bloc mediastinal nodal dissection, which might be more appropriate in higher risk patients, such as those with hilar and single-station mediastinal nodal metastasis. The kit may be less beneficial in high-volume academic Comprehensive Cancer Centers, with higher baseline pathologic nodal staging quality; however, the quality of pathologic nodal staging at high-volume Comprehensive Cancer Centers, although better, still has room to improve.33 Furthermore, the majority of lung cancer surgery is performed at community-level institutions, making our findings generalizable to the US population undergoing lung resections.3

In conclusion, our large-scale implementation study evaluated the effectiveness of a lymph node specimen collection kit in diverse environments within a defined catchment area spanning three US states with some of the highest per-capita lung cancer mortality. We found the kit to be safe and highly effective in improving the quality of pathologic nodal staging, potentially leading to further improvements in overall survival in diverse groups of lung cancer patients and institutions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by R01 CA172253.

We thank all members of the Thoracic Oncology Research Group (ThOR) over the years; hospital administrators, surgeons, operating room staff, pathologists, cancer registrars and other direct and indirect contributors at all institutions within the Mid-South Quality of Surgical Resection Consortium.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R01 CA172253].

Conflicts of interest:

Dr. Osarogiagbon owns patents for the lymph node specimen collection kit; owns stocks in Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, and Pfizer; has worked as a paid research consultant for the American Cancer Society, the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Triptych Healthcare Partners, and Genentech/Roche; and is founder of Oncobox Device, Inc. Dr. Smeltzer received a grant from the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Abbreviations

- ACS-CoC

American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer

- ACOSOG

American College of Surgeons Oncology Group

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiology

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- IASLC

International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer

- IRR

Incidence Rate Ratio

- IQR

interquartile range

- MS-QSR

Mid-South Quality of Surgical Resection

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfannschmidt J, Muley T, Bulzebruck H, Hoffmann H, Dienemann H. Prognostic assessment after surgical resection for non-small cell lung cancer: experiences in 2083 patients. Lung Cancer 55:371–377, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asamura H, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Lung Cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming 8th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 10:1675–1684, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little AG, Rusch VW, Bonner JA, et al. Patterns of surgical care of lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg 80:2051–2056, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osarogiagbon RU, Yu X. Nonexamination of lymph nodes and survival after resection of non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 96:1178–1189, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osarogiagbon RU, Yu X. Mediastinal lymph node examination and survival in resected early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Thorac Oncol 7:1798–1806, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen JW, Farooq A, O’Brien TF, Osarogiagbon RU. Quality of surgical resection for nonsmall cell lung cancer in a US metropolitan area. Cancer 117:134–142, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhagen AF, Schoenmakers MC, Barendregt W, et al. Completeness of lung cancer surgery: is mediastinal dissection common practice? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 41:834–838, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heineman DJ, Ten Berge MG, Daniels JM, Versteegh MI, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Wouters MW, Schreurs WH. The quality of staging non-small cell lung cancer in the Netherlands: data from the Dutch lung surgery audit. Ann Thorac Surg 102:1622–1629, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang W, He J, Shen Y, et al. Impact of examined lymph node count on precise staging and long-term survival of resected non-small-cell lung cancer: a population study of the US SEER database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. J Clin Oncol 35:1162–1170, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Commission on Cancer. Optimal Resources for Cancer Care. Patient care: Expectations and Protocols. 5.8 Pulmonary resection. Page 65. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/coc/optimal_resources_for_cancer_care_2020_standards.ashx. (accessed April 18, 2020).

- 11.Edwards JG, Chansky K, Van Schil P, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: analysis of resection margin status and proposals for residual tumor descriptors for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 15:344–359, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osarogiagbon RU, Miller LE, Ramirez RA, et al. Use of a surgical specimen-collection kit to improve mediastinal lymph-node examination of resectable lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 7:1276–1282, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 4:568–577, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darling GE, Allen MS, Decker PA, et al. Randomized trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in the patient with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non-small cell carcinoma: results of the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 141:662–670, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare. http://archive.dartmouthatlas.org/data/region (accessed January 7, 2019).

- 16.Hawkins NG, Sanson-Fisher RW, Shakeshaft A, D’Este C, Green LW. The multiple baseline design for evaluating population-based research. Am JPrevMed 33:162–168, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhoda DA, Murray DM, Andridge RR, Pennell ML, Hade EM. Studies with staggered starts: multiple baseline designs and group-randomized trials [published correction appears in Am J Public Health. 2014 Mar;104(3):e12]. Am J Public Health 101:2164–2169, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osarogiagbon RU, Ogbata O, Yu X. Number of lymph nodes associated with maximal reduction of long-term mortality risk in pathologic node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 97:385–393, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Non-small cell lung cancer. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (accessed February 8, 2016).

- 20.Commission on Cancer. Cancer Programs Practice Profile Reports (CP3R). Lung measure specifications. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/lungmeasuredocumentation_05272015.ashx (accessed February 8, 2016).

- 21.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors: TNM classification of malignant tumours. Chichester, West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Concato J, Peduzzi P, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards analysis. I. Background, goals, and general strategy. J Clin Epidemiol 48:1495–1501, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00510-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Feinstein AR, Holford TR. et al. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards regression analysis. II. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. J Clin Epidemiol 48:1503–1510, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee EW, Wei LJ, Amato DA: Cox-Type Regression Analysis for Large Numbers of Small Groups of Correlated Failure Time Observations, in Klein JP, Goel PK (eds): Survival Analysis: State of the Art. Dordrecht, Netherlands, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1992, pp 237–247 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes RA, Heron J, Sterne JAC, Tilling K. Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: multiple imputation is not always the answer. Int J Epidemiol 48:1294–1304, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 18:800–804, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osarogiagbon RU, Smeltzer MP, Faris N, Rami-Porta R, Goldstraw P, Asamura H. Comment on the proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 11:1612–1614, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smeltzer MP, Faris NR, Ray MA, Osarogiagbon RU. Association of pathologic nodal staging quality with survival among patients with non-small cell lung cancer after resection with curative intent. JAMA Oncol 4:80–87, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weaver SJ, Feitosa J, Salas E, Seddon R, Vozenilek JA: The theoretical drivers and models of team performance and effectiveness for patient safety, in Salas E, Frush K, (eds): Improving patient safety through teamwork and team training. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, pp 3–26 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osarogiagbon RU, Sareen S, Eke R, et al. Audit of lymphadenectomy in lung cancer resections using a specimen collection kit and checklist. Ann Thorac Surg 99:421–427, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med 312:1604–1608, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osarogiagbon RU, Faris NR, Stevens W, et al. Beyond Margin Status: Population-Based Validation of the Proposed International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Residual Tumor Classification Recategorization. J Thorac Oncol. 2020. March;15(3):371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osarogiagbon RU, Sineshaw HM, Lin CC, Jemal A. Institution-level differences in quality and outcomes of lung cancer resections in the United States. CHEST (in press 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.