Abstract

Abscission, a cell separation process, is an important trait that influences grain and fruit yield. We previously reported that BEL1-LIKE HOMEODOMAIN 4 (SlBL4) is involved in chloroplast development and cell wall metabolism in tomato fruit. In the present study, we showed that silencing SlBL4 resulted in the enlargement and pre-abscission of the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Micro-TOM) fruit pedicel. The anatomic analysis showed the presence of more epidermal cell layers and no obvious abscission zone (AZ) in the SlBL4 RNAi lines compared with the wild-type plants. RNA-seq analysis indicated that the regulation of abscission by SlBL4 was associated with the altered abundance of genes related to key meristems, auxin transporters, signaling components, and cell wall metabolism. Furthermore, SlBL4 positively affected the auxin concentration in the abscission zone. A dual-luciferase reporter assay revealed that SlBL4 activated the transcription of the JOINTLESS, OVATE, PIN1, and LAX3 genes. We reported a novel function of SlBL4, which plays key roles in fruit pedicel organogenesis and abscission in tomatoes.

Subject terms: RNAi, Plant molecular biology

Introduction

Organ abscission is critical for plant growth and development, as it enables the recycling of nutrients for continuous growth, development of appropriate organs, survival in case of disease, and reproduction1,2. Plant organ shedding refers to the abscission of some plant organs, such as flowers, leaves, fruits, and other tissues; it is caused by the coordinated actions of physiological processes, biochemical metabolism, and gene regulatory networks3. Abscission occurs at predetermined positions called abscission zones (AZs), and the abscission process includes differentiation of the AZ, acquisition of the competence to respond to abscission signals, activation of organ abscission, and formation of a protective layer4–7. Abscission initiation is considered to be triggered by the interaction of two hormones, auxin and ethylene8–10. During the late abscission stages, several key enzymes play an important role in organ shedding. Cellulase (Cel) and polygalacturonase (PG) participate in the degradation of the cell wall, and pectin methylesterase (PME) changes the chemical structure of the AZ via hydrolysis and induces cell wall and membrane degradation11.

Genetic analyses of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) have revealed that many transcription factors (TFs) are involved in AZ differentiation and abscission. JOINTLESS was shown to be directly related to the development of flower pedicels, inflorescence structure, fruit shape, and seed development, and the jointless mutant failed to develop AZs12,13. In addition to JOINTLESS, jointless-2 delayed the development and formation of tomato AZs13. Two MADS-box genes, Macrocalyx (MC) and SlMBP21, regulate pedicel AZ development, and the knockdown of these genes results in a jointless phenotype14,15. BLIND (Bl), a R2R3-class MYB TF gene, genetically interacts with JOINTLESS and plays an important role in abscission14,16,17. Lateral suppressor (Ls) partially impairs AZ development and causes malformation of meristem axillary buds. Furthermore, tomato ls mutants lack petals in their flowers18. BLADE ON PETIOLE1/2 (BOP1 and BOP2) were shown to be involved in the formation of Arabidopsis thaliana floral organ AZs, and the floral organs failed to abscise in the bop1/bop2 double mutant19.

The three-amino-acid-loop-extension (TALE) class genes encode TFs, such as KNOTTED-like (KNOX) and BEL1-like (BLH, BELL), and are typically involved in the regulation of meristematic activity20. TALE homeobox genes not only mediate plant development but also participate in plant organ separation. In A. thaliana, several members of the TALE family are reported to play central roles in regulating pedicel development. The KNAT/BP gene affects the development of A. thaliana floral AZs. In the bp mutant, the floral organs form more follicular cells and are abscised early due to the increased expression of KNAT2 and KNAT6 in the pedicel21–23. A. thaliana homeobox gene 1 (ATH1), a BELL TF member, plays a key role in the KNAT2 pathway to regulate pedicel development24. PENNYWISE (PNY) and POUND-FOOLISH (PNF) form heterodimers with KNOX proteins to regulate flowering initiation and inflorescence architecture25–28. SlBL4, a tomato bell-like gene, was shown to target chlorophyll synthesis and cell wall metabolism genes to control chloroplast development and cell wall metabolism in tomato fruit29. The expression of SlBL4 was upregulated in AZs10, and SlBL4 has high sequence similarity with ATH129, suggesting that it plays an important role in tomato pedicel AZ development.

Tomato is an excellent model for the study of the AZ, as it has distinct fruit/flower pedicels, rich genetic resources, and a stable genetic background. The present work identified a previously undefined role of the tomato BELL family gene bell-like homeodomain protein 4 (SlBL4) in the development of fruit pedicels. The pedicel AZ expanded more after anthesis, and the rate of fruit abscission was significantly increased starting from the abscission day in SlBL4 RNAi plants compared with WT plants. AZ transcriptomic and physiological analyses showed that the SlBL4 protein might play a role in the initiation and abscission of tomato AZs by regulating a variety of gene families and cell wall substructures.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Micro-Tom tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) were grown under greenhouse conditions with a 16 h light (25 °C ± 2 °C)/8 h dark (18 °C ± 2 °C) cycle and 80% relative humidity with 250 μmol m–2 s–1 of intense light.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, plant binary vector construction, and tomato transformation

For the expression analysis of SlBL4 in tomato pedicels at different stages, the materials were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for RNA extraction. Gene-specific primers are listed in Table S1. qRT-PCR was carried out as described previously30.

The promoter sequence of SlBL4 was amplified from tomato genomic DNA with the primers SlBL4-PF and SlBL4-PR (Table S1). The promoter fragment of SlBL4 was digested with Sal I/BamH I and ligated into the plant binary vector pLP100 containing the GUS reporter gene, yielding the reporter vector pLP100pSlBL4-GUS. Transgenic plants were obtained by the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method31. The transgenic lines were selected and confirmed by qPCR and GUS staining according to the methods of Yan32. The SlBL4-RNAi plants were obtained according to the method of a previous study29. Three representative transgenic lines (L19, L22, and L23) were selected for further analysis, and all experiments were performed using homozygous lines of the T3 generation.

Auxin and ethylene treatment

For auxin treatment, tomato seeds (n = 30) from the wild type (WT) and SlBL4 RNAi lines were soaked in MS medium supplemented with different concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (Sigma, USA) for 14 days in a culture chamber. Primary and lateral root numbers and lengths were measured, and photographs were taken after 14 days of growth. For ethylene treatment, the same seeds were soaked in MS medium supplemented with 1 μM ACC for 7 days in the dark culture chamber as described above. Root and hypocotyl elongation were observed and measured after 7 days of growth. All experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

Floral explants were prepared by excising freshly opened flowers, including the pedicel AZ. For the IAA treatment, the pedicel ends of explants were inserted into a layer of 1/2 MS agar with 50 μg/g IAA in a Plexiglass box and placed in a tray filled with a layer of water. For the ethylene treatment, the pedicel ends of explants were treated similarly, but ethylene gas was added to the box at a final concentration of 20 µl/L. The abscised pedicel explants were counted at 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 72, 84, 96, 108, and 120 h after treatment. Three biological replicates were performed, and each treatment group contained ~50 explants.

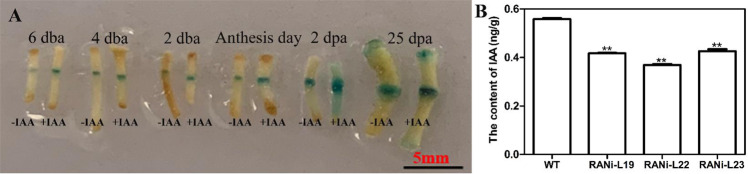

GUS Staining and auxin content measurement

Tomato inflorescences were placed into GUS staining buffer comprising 2.0 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-glucuronic acid, 0.1 M Na3PO4 (pH 7.0), 1.0 mM K3 Fe (CN)6, 10 mM Na2EDTA and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100. The inflorescences were vacuumed for 30 min and incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 16 h. GUS-stained tissues were washed with 70% (v/v) ethanol and observed under a light microscope.

Floral explants including the pedicel AZ were prepared by excising the tissues at 6, 4, and 2 days before anthesis (dba), on the anthesis day, and at 2 and 25 days post anthesis (dpa). For IAA treatment, the pedicel ends of explants were inserted into a layer of 1/2 MS agar with 50 μg/g IAA, and the floral explants were stained with GUS after 24 h of treatment.

The IAA content was measured by acquisition ultraperformance liquid chromatography (Acquity UPLC; Waters). Fifty pedicel AZ segments were collected from the pedicel at the abscission stage, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for IAA quantification according to the literature33.

Microscopy and TEM observation

For histological analysis, tissue samples were collected from the pedicel at 25 dpa and immersed in FAA solution, placed under vacuum for 15 min, and incubated at 25 °C for 72 h. The samples were dehydrated, stained, and observed under a microscope according to the literature32. At anthesis, flowers of WT plants and SlBL4 RNAi line tomatoes were emasculated and subsequently counted and sampled for anatomical assessment at 10 dpa. For the histological assessment of SlBL4pro::GUS expression, tissue samples were collected from the pedicel of pSlBL4-GUS transgenic tomato at the following times: at 6, 4, 2 dba; on the anthesis day; and at 2, 25 dpa. The pedicel of the AZ at 25 dpa was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) according to the literature34.

RNA-seq analysis

Pedicel samples, including those at three stages (0 dpa, 25 dpa, and the fruit break stage), were dissected using a sharp razor blade into three segments (distal, AZ, and proximal tissues), and an AZ segment of ~2 mm was placed in liquid nitrogen immediately. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three biological replicates were performed for each sample for both SlBL4-RNAi and WT plants. The RNA-Seq libraries were constructed and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at the Wuhan Genome Institute (BGI, China). The raw sequences were processed by removing the adaptor and low-quality sequences. The expression levels of DEGs were normalized by the fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FRKM) method using Cuffdiff software (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/). A false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05 was used to determine the threshold for DEGs. GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were conducted according to previously described methods (https://github.com/tanghaibao/goatools) and KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/home.do).

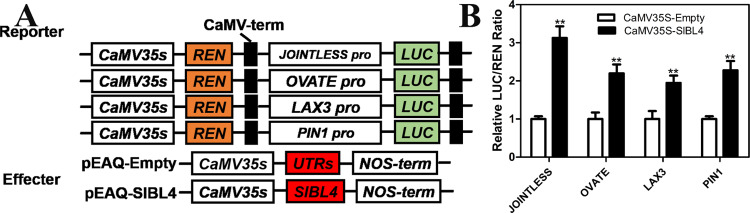

Dual-luciferase transient expression assay

For effector vector construction, the full-length coding sequence of SlBL4 was amplified and then cloned into the pEAQ-Empty vector29. For reporter vector construction, the promoters of the JOINTLESS, OVATE, LAX3, and PIN1 genes were cloned into a pGreenII 0800-LU vector35. A dual-luciferase transient expression assay for SlBL4 was carried out using tobacco leaves (Nicotiana benthamiana). A dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, USA) was used to measure the activities of LUC and REN luciferase according to the manufacturer’s instructions on a Luminoskan Ascent microplate luminometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Six biological repeats were performed for each pair of vector combinations. The primer sequences used for the vector construct are shown in Table S1.

Results

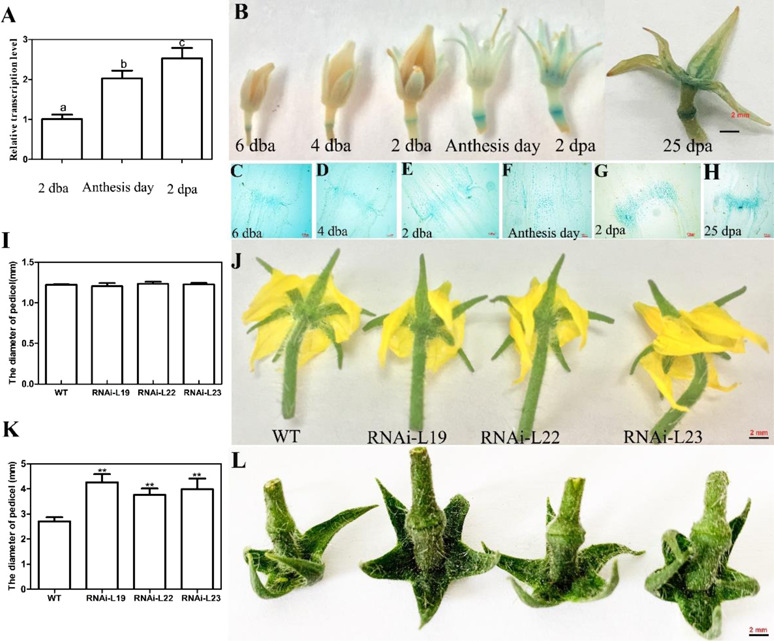

SlBL4 expression is associated with AZ development

SlBL4 was reported to be predominately expressed in pedicel AZs in tomato10. To clarify the involvement of SlBL4 in tomato pedicel abscission, the transcript level of SlBL4 was analyzed in pedicel AZs from the floral bud stage to the flowering stage (2 days before anthesis, 2 dba; anthesis day, AS; 2 days post anthesis, 2 dpa) by qRT-PCR. The transcript levels of SlBL4 showed progressive increases at 2 dba, AS and 2 dpa (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, pSlBL4-GUS transgenic tomato was generated according to the literature32. Consistent with the qRT-PCR results, GUS expression was obviously visible in the AZ and showed an increasing expression pattern during anthesis development (Fig. 1B). The anatomic analysis was performed to more precisely assess the SlBL4 expression pattern in the AZ. The results showed that GUS expression was obviously visible in the whole pedicle before anthesis and increased after anthesis in the pedicle AZ (Fig. 1C–H). This AZ-specific expression pattern indicated that SlBL4 possibly participated in the abscission process.

Fig. 1. Expression analysis of SlBL4 and the pedicel abscission phenotype of the RNAi plants.

A Expression analysis of SlBL4 in different stages of tomato pedicel abscission; 2 dba, 2 days before anthesis; 2 dpa, 2 days post anthesis. The quantitative PCR data represent mean values for three independent biological replicates, and Duncan’s multiple range test was performed to compare samples in different groups. The standard errors are indicated by vertical bars. B SlBL4pro::GUS expression at 6, 4, 2 dba: 6, 4, and 2 days before anthesis; anthesis day; 2, 25 dpa: 2 and 25 days post anthesis; C–H Anatomic analysis of the floral pedicel abscission zone of SlBL4pro::GUS plants: C 6 dba; D 4 dba; I 2 dba; F anthesis day; G 2 dpa; H 25 dpa. I The diameter of the pedicel abscission zone on the anthesis day. J Anthesis day pedicel. K The diameter of the pedicle abscission zone on 25 dpa. L 25 dpa pedicel. WT wild type, RNAi-L19, RNAi-L22, RNAi-L23 three different lines of SlBL4 RNAi plants. Scale bars: 2 mm

Silencing SlBL4 augmented the pedicel and promoted abscission

In this study, we used a 35S::SlBL4-RNAi silencing construct to generate SlBL4 knockdown Micro-Tom tomato plants. The transgenic tomato exhibited SlBL4 expression that was reduced by 20-80% compared with that of the WT plant29. At 25 days after flowering, the floral pedicel AZ expanded to a greater extent in SlBL4 knockdown plants than in the control WT plants, whereas no obvious difference was found at the anthesis stage (Fig. 1C–F). The AZ diameters were 3.76–4.26 mm in the three SlBL4 RNAi lines and 39–57% higher than those in the WT plants at 25 days after flowering (Fig. 1E, F).

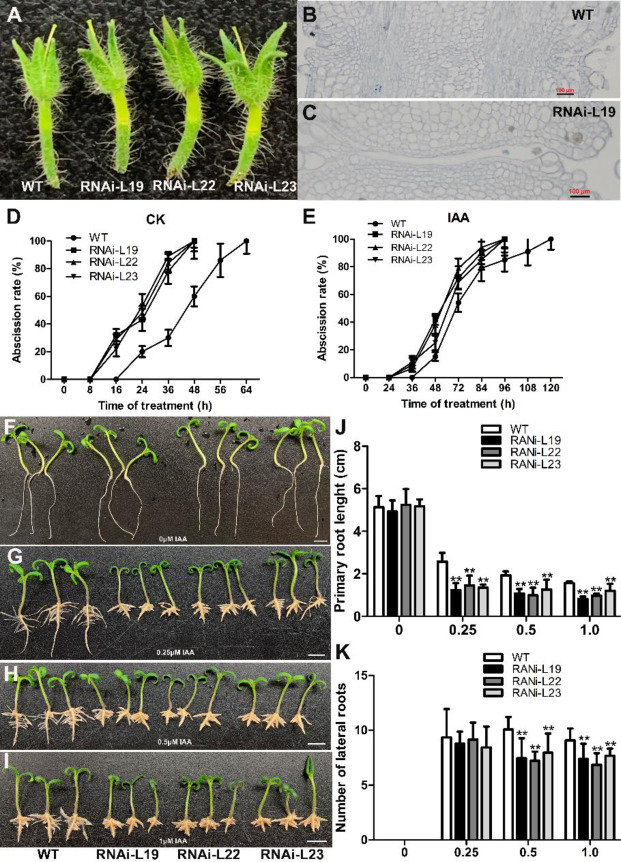

In emasculated flowers, the pedicel abscised at 10 and 14 days after emasculation in the RNAi lines and WT plants, respectively (Fig. 2A). Anatomic analysis of the floral pedicel AZ at 10 days after emasculation showed that the unpollinated flowers were abscised in the AZ in the SlBL4 RNAi lines, but the cells began to separate at the AZ in the WT plants (Fig. 2B, C).

Fig. 2. Effects of exogenous auxin on SlBL4 RNAi plants.

A Phenotypes of flower droppings after emasculation at 10 days. B, C Microsection of a 10-day floral pedicel abscission zone after emasculation in RNAi plants and WT tomato. D, E Abscission rate; D Timing of floral abscission-zone explants of tomato flowers following exposure to 1/2 MS; E Timing of floral abscission-zone explants of tomato flowers following exposure to 1/2 MS with 50 μg/g IAA. F–I Root development in WT plants and three independent SlBL4 RNAi lines (L19, L22, and L23) assessed in two-week-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium containing different concentrations of IAA (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 μM). J The lengths of primary roots in the SlBL4 RNAi lines (L19, L22, and L23). K The lateral root numbers in the SlBL4 RNAi lines (L19, L22, and L23); WT wild type, RNAi-L19, RNAi-L22, and RNAi-L23 three different lines of SlBL4 RNAi plants. The asterisks indicate significant differences at P < 0.01 (**) as determined by the t-test

Sexton and Roberts reported that auxin and ethylene participate in the regulation of abscission in dicotyledonous plants36. To analyze the effect of IAA on RNAi line flower abscission, flowers were removed and replaced by 1/2 MS containing 50 μg/g IAA. The explants began to abscise at 8 h in the RNAi lines but at 16 h in the WT plants without IAA treatment, whereas they began to abscise at 24 h in the RNAi lines but at 36 h in the WT plants after IAA treatment (Fig. 2D, E). These results demonstrated that the RNAi lines exhibited an early-abscission phenotype and that IAA treatment could rescue this phenotype. For ethylene (20 μL/L) treatment of the explants, there was no difference between the RNAi lines and the WT plant in terms of the abscission rate (Fig. S1).

To investigate whether the downregulation of SlBL4 alters auxin sensitivity, the root phenotype was further investigated. The RNAi lines exhibited shorter primary roots after IAA treatment compared with those of the WT seedlings. Lower lateral root numbers were observed in the RNAi lines after 0.5 and 1.0 μM IAA treatment compared with those of the WT seedlings (Fig. 2F–K). There was no difference between the RNAi lines and WT plant seedlings treated with 1 μM ACC for 7 days in the dark culture chamber (data not shown). These results suggested that the SlBL4 RNAi tomato plants were sensitive to auxin in terms of root growth.

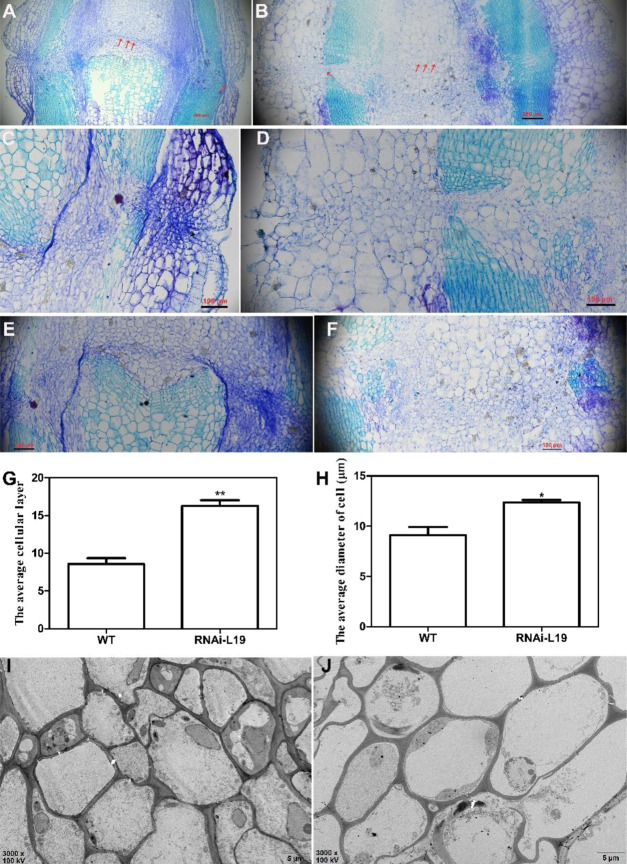

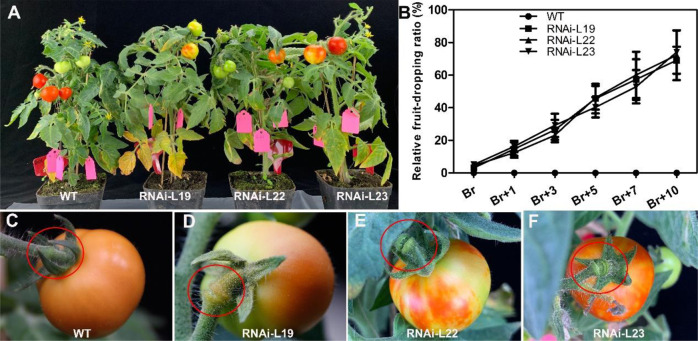

Anatomic analysis of the floral pedicel AZ showed that no obvious AZ formed, and more epidermis cell layers were observed in the SlBL4 RNAi lines than in the WT (Fig. 3A–F). The epidermal cell layers and cell diameter were obviously increased by 90% and 36%, respectively, in the floral pedicel AZ of the SlBL4 RNAi lines compared with the WT plants (Fig. 3G, H). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations showed that epidermal cells were enlarged in the SlBL4 RNAi lines compared with the WT (Fig. 3I, J). Silencing SlBL4 positively affected the formation of pedicels in tomato plants. At the break (Br) stage, the fruit began to drop earlier in the SlBL4 RNAi lines than in the WT plants (Fig. 4A and C–F). The ratio of fruit abscission was significantly increased on different Br days in SlBL4 RNAi plants, whereas no fruit dropping was observed in the WT plants at the same stage (Fig. 4B). These observations indicated that the suppression of SlBL4 activated pedicel abscission.

Fig. 3. Anatomic analysis of the fruit pedicel abscission zone of the SlBL4 RNAi plant.

A–F Cross-sections of the fruit pedicel abscission zone at the 25 dpa stage as revealed by toluidine blue staining. A, C, E WT; B, D, and F SlBL4 RNAi-L19. G, H The epidermal cell layers per cell in the fruit pedicel abscission zone of 25 dpa fruit pedicels in WT and SlBL4 RNAi-L19 plates; H The epidermal diameter per cell in the fruit pedicel abscission zone of 25 dpa fruit pedicels in WT and SlBL4 RNAi-L19 plants. I, J Transmission electron micrographs of the fruit pedicels of SlBL4 RNAi-L19 and WT tomato at 25 dpa; I WT; J SlBL4 RNAi-L19; scale bars: 5 μm; dpa day post anthesis, WT wild type

Fig. 4. The fruit-dropping phenotypes of the SlBL4 RNAi plants.

A, C–F The fruit-dropping phenotypes. B Fruit-dropping statistical data. WT wild type,RNAi-L19, RNAi-L22, and RNAi-L23 three different lines of SlBL4 RNAi plants

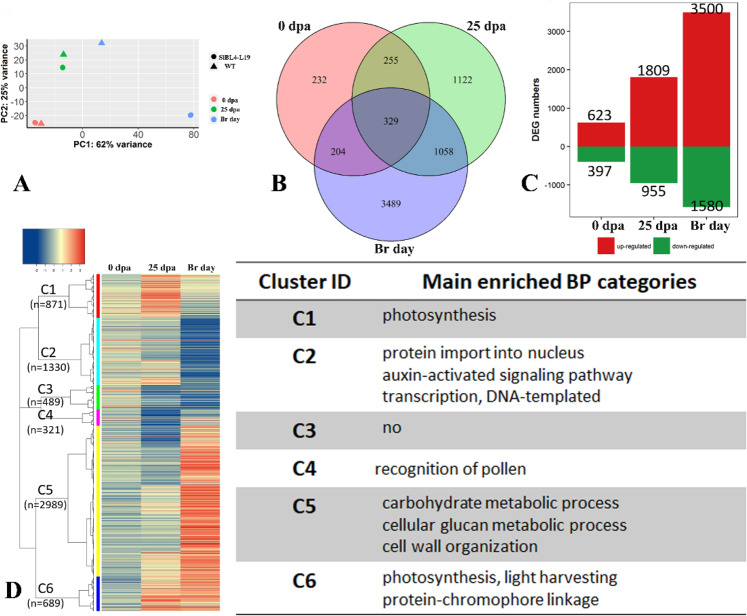

RNA-seq and DEG analyses of pedicels of SlBL4 RNAi lines and wild-type plants

RNA-seq was performed to investigate the transcriptional mechanisms underlying the phenotype of thickened and pre-abscission pedicels in the SlBL4 RNAi-L19 plant. DEGs (differentially expressed genes) were obtained for SlBL4 RNAi-L19 plants compared with the WT plant in the AZ at the AS, 25 dpa, and Br stages. Correlation analysis and PCA demonstrated that the RNA-seq data for the RNAi-L19 plant pedicel samples were clearly differentiated from those for the WT plants at the 25 dpa and Br stages with good repeatability (Fig. S2 and Fig. 5A). The DEGs were categorized into three major classes, namely, cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes, by GO annotation (Fig. S3A–C). KEGG pathway analysis showed that the DEGs were involved in metabolism, genetic information processing, and organismal systems (Fig. S3D–F). Under the criterion of a FDR ≤ 0.001, 329 DEGs were commonly upregulated or downregulated at the three developmental stages of tomato (Fig. 5B). In SlBL4 RNAi AZs, 623, 1809, and 3500 genes were upregulated, and 397, 955, and 1580 genes were downregulated, respectively, at the anthesis day, 25 dpa, and Br stages compared with the WT plant (Fig. 5C). Cluster analysis showed that the DEGs were associated with the auxin-activated signaling pathway, the cellular glucan metabolic process, cell wall organization, light harvesting, photosynthesis, and protein-chromophore linkage (Fig. 5D and Tables S2–7).

Fig. 5. The DEG analysis of SlBL4 RNAi line 19 compared with wild-type tomato.

A Principal component analysis (PCA) of gene expression data from the RNA-seq libraries. B Venn diagram of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between SlBL4 RNAi and wild-type plants at three different fruit pedicel stages. C Upregulated (red bar) and downregulated (green bar) DEGs between SlBL4 RNAi and wild-type plants at the three developmental stages of fruit pedicel. D Cluster analysis of DEGs at the three developmental stages of fruit pedicel

SlBL4 regulates the small cells of pedicel AZs

The silencing of SlBL4 caused enlargement of the epidermal cells and disappearance of small cells at the separation zone compared with the WT plant (Fig. 3). In the transcriptomic analysis, the expression of wuschel (WUS), cup-shaped cotyledon 2 (CUP2), JOINTLESS and ovate family proteins was decreased significantly, and Bl, MYB transcription factor (MYB78), and LOB domain protein 1 (LBD1) were substantially upregulated in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage (Table 1). WUS (Solyc02g083950), CUP (Solyc07g06284), JOINTLESS (Solyc11g010570), and OVATE (Solyc02g085500) were downregulated by 4.3-, 1.77-, 1.09-, and 2.17-fold, and Bl (Solyc11g069030), MYB78 (Solyc05g053330), and LBD1 (Solyc11g072470) were upregulated by 4.57-, 3.39-, and 4.8-fold, respectively. Thus, these seven TF genes were likely involved in the regulation of abscission onset in the SlBL4 RNAi plant. These genes were vital for maintaining undifferentiated cells in the AZ of tomato.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in the fruits of wild type and SlBL4 RNAi plants at three stages of development

| Gene ID | Annotation | Fold change (log2) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 d | 25 d | Br | 0 d | 25 d | Br | ||

| Transcription factor | |||||||

| Solyc02g083950 | Wuschel (WUS) | −1.41 | −1.42 | −4.30 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g062840 | Protein CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 2 (CUP) | −0.42 | −0.40 | −1.77 | 0.113 | 0.285 | <0.001 |

| Solyc11g010570 | JOINTLESS | 0.05 | 0.40 | −1.09 | 0.747 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g085500 | Ovate family protein | 0.13 | 0.26 | −2.17 | 0.201 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Solyc11g069030 | MYB transcription factor (BLIND) | −1.03 | −0.03 | 4.57 | 0.007 | 0.977 | <0.001 |

| Solyc05g053330 | MYB transcription factor (MYB78) | −0.83 | −1.4 | 3.39 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc11g0 72470 | LOB domain protein 1 | −1.35 | −0.54 | 4.80 | <0.001 | 0.063 | <0.001 |

| Solyc05g010000 | IDA | −1.34 | 0.000 | 7.656 | 0.262 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Auxin-related | |||||||

| Solyc12g005310 | Auxin responsive GH3 gene family (GH3-15) | 0.91 | 3.11 | 5.88 | 0.072 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g107390 | Auxin responsive GH3 gene family (GH3-2) | 0.11 | −1.97 | 2.63 | 0.819 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g064830 | Indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase 3-3 | −1.46 | −1.24 | 2.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g068490 | Probable indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3.5 | 1.26 | 1.10 | −0.93 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Solyc05g006220 | IAA-amino acid hydrolase | 0.06 | −1.26 | 0.55 | 0.801 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g073060 | IAA-amino acid hydrolase 6 | 0.17 | 0.81 | 1.56 | 0.164 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc10g079640 | IAA-amino acid hydrolase 9 | 0.03 | 1.31 | 2.04 | 0.909 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g096340 | SAUR family protein (SAUR2) | −0.24 | 1.38 | 0.61 | 0.029034 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g110560 | SAUR3 | 0.61 | 0.95 | 1.12 | 0.064 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g062230 | SAUR32 | −0.33 | −0.81 | 1.78 | 0.520 | 0.117 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g042490 | SAUR33 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 1.73 | 0.018 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g082510 | SAUR35 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 2.10 | 0.009 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g082520 | SAUR36 | −0.28 | 0.00 | 3.20 | 0.339 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g082530 | SAUR37 | −0.20 | −1.85 | 4.34 | 0.535 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g097510 | SAUR38 | 0.00 | −0.68 | 6.59 | 1.000 | 0.483 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g033590 | SAUR50 | 0.25 | −0.88 | 1.58 | 0.262 | 0.0076 | <0.001 |

| Solyc04g081270 | SAUR52 | 0.76 | 3.41 | 5.11 | 0.211 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc05g05643 0 | SAUR56 | −0.17 | −0.11 | 2.22 | 0.739 | 0.887 | <0.001 |

| Solyc05g056440 | SAUR57 | 0.16 | −0.19 | 2.53 | 0.829 | 0.798 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g07265 0 | SAUR61 | 0.00 | −1.10 | 2.05 | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g014620 | SAUR63 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 1.56 | 1 | 0.671 | <0.001 |

| Solyc09g009980 | SAUR70 | −1.24 | 1.09 | 3.52 | 0.0294 | 0.105 | <0.001 |

| Solyc10g018340 | SAUR71 | −1.09 | −3.20 | 2.02 | 0.302 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g124020 | SAUR72-like | 1.64 | 0.85 | 2.59 | 0.145 | 0.451 | 0.004 |

| Solyc10g052560 | SAUR75 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 2.40 | 0.954 | 0.369 | 0.005 |

| Solyc09g065850.2 | Auxin-responsive protein IAA (IAA3) | −0.16 | −1.30 | −3.11 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g053840 | IAA4 | 0.32 | 0.16 | −2.31 | 0.002 | 0.100 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g053830 | IAA7 | 0.07 | −0.46 | −2.71 | 0.533 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g008590 | IAA10 | 1.21 | 0.51 | 1.09 | <0.001 | 0.061 | 0.035 |

| Solyc12g096980 | IAA11 | 1.50 | −0.39 | −1.40 | 0.003 | 0.260 | 0.029 |

| Solyc09g064530 | IAA12 | 0.78 | −0.02 | −1.61 | <0.001 | 0.937 | <0.001 |

| Solyc04g076850.2 | IAA9 | 0.41 | 0.29 | −1.25 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g097290 | IAA16 | 0.17 | 0.45 | −3.62 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g021820 | IAA21 | −0.24 | −0.48 | −2.30 | 0.425 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g008580 | IAA22 | 0.36 | −1.61 | −4.19 | 0.119 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc09g083280.2 | IAA23 | 0.29 | −1.52 | −2.09 | 0.007 | <0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Solyc09g083290 | IAA24 | −0.11 | −0.94 | −4.60 | 0.619 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc09g090910 | IAA 25 | 0.85 | −0.58 | −2.81 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g019450 | IAA33 | −0.60 | 2.82 | 5.20 | 0.674 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g066020 | IAA 36 | 1.78 | 0.09 | −3.95 | <0.001 | 0.717 | <0.001 |

| Solyc05g047460 | Auxin Response Factor 7B | −0.66 | −0.55 | −1.23 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g082630 | Auxin Response Factor 9A | 1.23 | 1.21 | −1.32 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.041151 |

| Solyc07g042260 | Auxin response factor (ARF19) | −1.02 | 0.12 | −0.20 | <0.001 | 0.120 | 0.017 |

| Solyc11g013310 | Auxin transporter-like protein 3 (LAX3) | −0.25 | −1.53 | −0.34 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g111310 | Auxin transporter-like protein 3 (LAX2) | 0.70 | 0.30 | −1.51 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g118740 | SlPIN1 | 0.64 | 0.37 | −3.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g037550 | SlPIN-LIKES 3 | 0.25 | −0.38 | −2.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g068410 | SlPIN5 | 1.05 | −0.20 | −2.60 | 0.010 | 0.702 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g059730 | SlPIN6 | 0.54 | 0.65 | −2.04 | 0.146 | 0.123 | <0.001 |

| Solyc10g080880 | SlPIN7 | 0.31 | 0.51 | −2.08 | 0.044 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Cell wall hydrolysis/modification | |||||||

| Solyc09g091430 | Probable pectate lyase 8 | 0.08 | 1.54 | 6.90 | 0.278 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g075620 | Probable pectinesterase 53 | 0.844 | 1.765 | 5.319 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g064190 | Pectinesterase 3 | −1.078 | 0.625 | 4.501 | <0.001 | 0.689 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g064180 | Pectin esterase (PME2.1) | 1.455 | 2.704 | 4.271 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g102350 | Pectin acetylesterase 12 | 0.341 | 1.052 | 3.584 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc11g005770 | Pectinesterase | −0.39 | 0.18 | 1.98 | <0.001 | 0.035 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g067630 | Polygalacturonase 1 | −1.59 | 1.60 | 12.41 | 0.153 | 0.130 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g067640 | Polygalacturonase 2 | −1.22 | 0.04 | 11.55 | 0.338 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Solyc12g019230 | Polygalacturonase-like | −2.55 | −0.44 | 7.50 | 0.001 | 0.778 | 0.000 |

| Solyc04g015530 | Dehiscence polygalacturonase | −1.91 | −0.17 | 7.33 | <0.001 | 0.895 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g081480 | Polygalacturonase-like protein | 0.381 | 1.193 | 3.706 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc02g080210 | Polygalacturonase-2a | −0.32 | 2.29 | 2.24 | 0.800 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc12g096750 | Polygalacturonase 4 | −1.68 | 1.51 | 5.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc12g096740 | Polygalacturonase 5 | −4.05 | −1.6 | 8.57 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc12g019180 | Polygalacturonase 7 | −0.49 | 1.24 | 6.8 | 0.758 | 0.170 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g094970 | Polygalacturonase family protein | −2.75 | −2.40 | 4.41 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g006700 | Peroxidase | −2.19 | 1.06 | 3.87 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g081620 | Endo-1,4-beta-glucanase precursor (Cel1) | 0.23 | 1.50 | 5.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc09g010210 | Endo-1,4-beta-glucanase precursor (Cel2) | 0.38 | 0.50 | 4.91 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc09g075360 | Endo-1,4-beta-glucanase precursor (Cel4) | −0.29 | 0.84 | 2.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc11g040340 | Endo-1,4-beta-glucanase precursor (Cel7) | 0.85 | −0.25 | 2.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g082250 | Endo-1,4-beta-glucanase precursor (Cel8) | −0.05 | 0.18 | 2.00 | 0.238 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g009380 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH2) | 1.17 | 5.17 | 6.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g093110 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH3) | 0.64 | 0.30 | 1.42 | <0.001 | 0.170 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g093120 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH3) | 0.20 | 0.01 | 3.06 | 0.24 | 0.990 | <0.001 |

| Solyc03g093130 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH3) | 0.00 | 0.52 | 1.73 | 1.000 | 0.062 | <0.001 |

| Solyc11g065600 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH4) | 1.21 | 1.10 | 1.52 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g091920 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH7) | 0.87 | 2.85 | 1.98 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc12g011030 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH9) | 0.73 | 0.19 | 4.89 | <0.001 | 0.420 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g056000 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH10) | −0.49 | −0.56 | 2.90 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc12g017240 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH11) | −0.10 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.29 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc07g052980 | Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XTH16) | 0.51 | 1.27 | 0.46 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g112000 | Expansin-like protein precursor 1 (EXLA1) | −0.18 | −0.62 | 2.69 | 0.034 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc10g086520 | Expansin (EXPA6) | 1.09 | 0.76 | 4.06 | 0.006 | 0.130 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g005560 | Expansin 9 (EXPA9) | 0.64 | 0.52 | 2.84 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g076220 | Expansin18 (EXPA18) | 0.63 | 0.41 | 2.71 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc08g077910 | Expansin 45 (EXPA45) | −0.852 | 0.041 | 9.25 | 0.540 | 0.995 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g051800 | Fruit ripening regulated expansin1 (EXP1) | 0.69 | −0.01 | 4.01 | <0.001 | 0.955 | <0.001 |

| Solyc06g049050 | Expansin (EXP2) | 0.85 | 2.06 | 2.06 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc04g081870 | Expansin precursor (EXP11) | 0.42 | 0.87 | 4.64 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc01g090810 | Beta-expansin precursor(EXPB1) | −0.26 | −2.84 | 9.59 | 0.847 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Solyc05g007830 | Alpha-expansin 1 precursor | 1.15 | 0.17 | 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

To examine the potential target genes of SlBL4 in fruit pedicel development, the promoter sequences were analyzed in JOINTLESS and OVATE, which revealed the SlBL4 binding (G/A) GCCCA (A/T/C) motif29. Transient dual-luciferase assays were performed to examine whether SlBL4 could directly activate or suppress the expression of the JOINTLESS and OVATE genes. Tobacco leaves were cotransformed with LUC reporter vectors driven by the promoters of the JOINTLESS and OVATE genes together with effector vectors carrying the CaMV35S promoter-driven SlBL4 gene. Transient dual-luciferase assays showed that overexpression of SlBL4 significantly increased the luciferase activity driven by the promoters of JOINTLESS and OVATE compared with that of the empty control (Fig. 6A, B), indicating that SlBL4 activated the transcription of JOINTLESS and OVATE. The expression levels of WUS, CUP, and Bl were determined by RT-qPCR, and the results coincided with the RNA-seq results (Fig. S4).

Fig. 6. SlBL4 directly activates the expression of genes related to fruit pedicel development.

A Diagram of the reporter and effector constructs used in the transient dual-luciferase assays in leaves of tobacco seedlings; LUC, firefly luciferase; REN, Renilla luciferase. B In vivo interactions of SlBL4 with the promoters obtained from the JOINTLESS, OVATE, LAX3 or PIN1 transient assays in tobacco leaves. The data are presented as the means (±SE), n = 6. Significant differences compared with the WT were determined by Student’s t-test: **P < 0.01

Silencing SlBL4 affected the auxin level in AZ

Auxin plays critical role in the maintenance of fruit attachment to plants3. There were 103 auxin-related DEGs in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the pre-abscission AZs. This included auxin-responsive genes, such as Aux/IAA, Gretchen Hagen 3 (GH3), small auxin upregulated RNA (SAUR), and auxin response factor (ARFs), and auxin transport-related genes, such as PIN (pin-formed protein) and like auxin (LAX) (Table 1).

For instance, ARF7B (Solyc05g047460), ARF9A (Solyc08g082630), and ARF19 (Solyc07g042260) were downregulated by 1.23-, 1.32-, and 0.2-fold, respectively, in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage. LAX2 (Solyc01g111310) and LAX3 (Solyc11g013310) were downregulated by 0.34- and 1.51-fold, respectively, in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage. SlPIN1 (Solyc03g118740), SlPIN-likes 3 (Solyc02g037550), SlPIN5 (Solyc01g068410), SlPIN6 (Solyc06g059730), and SlPIN7 (Solyc10g080880) were downregulated by 3.08-, 2.79-, 2.60-, 2.04-, and 2.08-fold, respectively, in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage (Table 1). The promoter sequences were also analyzed in LAX3 and SlPIN1, which revealed the SlBL4 binding (G/A) GCCCA (A/T/C) motif. Transient dual-luciferase assays showed that overexpression of SlBL4 significantly increased the luciferase activity driven by the promoters of LAX3 and SlPIN1 compared with that of the empty control (Fig. 6A, B), indicating that SlBL4 activated the transcription of LAX3 and SlPIN1.

To analyze the effect of IAA on the floral pedicel AZ of SlBL4pro::GUS plants, the flower was removed and replaced by 1/2 MS medium containing 50 μg/g IAA for 24 h, which accelerated GUS expression in the pedicel AZ compared with that in the control (-IAA) (Fig. 7A). In addition, we examined the IAA concentrations in tomato pedicel AZs by acquisition ultraperformance liquid chromatography. The IAA concentrations in the AZs of SlBL4 RNAi plants were lower than those in the AZs of WT plants (Fig. 7). The expression of ARF9A and SlPIN7 was determined by qRT-PCR, and the results coincided with the RNA-seq results (Fig. S4). In conclusion, silencing SlBL4 influenced the auxin efflux, signaling, and content in tomato pedicels.

Fig. 7. Effects of IAA treatment on the floral pedicel abscission zone of SlBL4pro::GUS plants and auxin concentrations in pedicel AZs.

A Effects of exogenous auxin (+IAA) and control treatment (-IAA) on the floral pedicel abscission zones of SlBL4pro::GUS plants; 6 dba, 4 dba, 2 dba, anthesis day, 2 dpa, 25 dpa; dba: day before anthesis; dpa: day post anthesis. B The content of IAA; standard errors are indicated by vertical bars. The asterisks indicate significant differences at P < 0.01 (**) as determined by the t-test; WT wild type, RNAi-L19, RNAi-L22, RNAi-L23 three different lines of SlBL4 RNAi plants

Suppression of SlBL4 induces the expression of genes encoding cell wall hydrolytic enzymes

The expression of genes encoding cell wall degrading and remodeling enzymes, including pectinases (PG, PL), cellulase (Cel), xyloglucan endotransglucosylase-hydrolase (XTH), and expansin (EXP), was reported to be induced in response to the abscission stimulus. Our transcriptome analyses showed that many of the genes mentioned above were expressed at higher levels in the SlBL4 RNAi line than in the WT plant at the abscission stage. Among the DEGs, 16 PG/PL genes, 5 Cel genes, 10 XTH genes, 10 EXP genes, and 1 peroxidase (POD) gene were found (Table 1). For instance, PG1 (Solyc02g067630), PG2 (Solyc02g067640), and PE (Solyc11g005770) were upregulated by 12.41-, 11.55-, and 1.98-fold, respectively. Cel1 (Solyc08g081620) was upregulated by 5.38-fold. XTH2 (Solyc07g009380) was upregulated by 6.05-fold. EXPA45 (Solyc08g077910) and EXPB1 (Solyc01g090810) were upregulated by 9.25- and 9.59-fold, respectively. These genes were vital for cell wall remodeling and middle lamella degradation at the late stages of the abscission process. The expression levels of PG1, PE, XTH2, and EXPA45 were evaluated by RT-qPCR, and the results coincided with the RNA-seq results (Fig. S4).

Discussion

BELL TFs play various roles in plant morphology and fruit development29,37,38, whereas they are seldom reported to be involved in fruit pedicel organogenesis and abscission. Here, we reported that SlBL4 is an important regulator of fruit pedicel organogenesis and abscission in tomatoes.

SlBL4 regulated WUS, Bl, CUP, OVATE, and Ls in the regulation of competency to respond to abscission-promoting signaling

Abscission can occur at four key steps, namely, differentiation of the AZ, acquisition of the competence to respond to abscission signals, activation of organ abscission, and formation of a protective layer on the main body side of the AZ6,7,39. We elucidated the role of SlBL4 in abscission by observing the SlBL4 RNAi fruits at 25 dpa. Our anatomic analysis of the floral pedicel AZ showed greater enlargement of the epidermal cells and disappearance of the small cells at the separation zone in the SlBL4 RNAi plant pedicel compared with the control (Fig. 3). These results suggested that the size and proliferation of the AZ cells are likely to be activated due to the repression of SlBL4 expression. The involvement of TF genes, such as WUS, Bl, CUP, JOINTLESS, OVATE, LBD1, and Ls, was evident in the anthesis pedicel AZs14,40–42. Moreover, our analyses also revealed AZ-specific downregulation of WUS, CUP, JOINTLESS, and OVATE and upregulation of Bl, MYB78, and LBD1 in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage (Table 1). WUS, OVATE, and CUP function coordinate to maintain cells in an undifferentiated state and to maintain a small cell size, which are critical for meristem activities7,40,42,43. Therefore, the reduced expression of WUS, CUP, JOINTLESS, and OVATE caused by an abscission signal may have resulted in enlargement of the separation zone cells for the onset of abscission in the RNAi line compared with the WT plant. Our results indicated that SlBL4 directly activated JOINTLESS and OVATE expression, thus accounting for the disappearance of the small cells at the separation zone in the SlBL4 RNAi plant pedicel (Fig. 6). The Bl gene, which encodes the R2R3 class MYB TF, controls lateral meristem development17,44 and is upregulated in the AZ-formation stage in tomato14. In combination with the SlBL4 expression pattern in AZs, this finding explains why SlBL4 contributes to the maintenance of the undifferentiated status of cell proliferation and differentiation of flower pedicel AZs by affecting the expression of meristem activity genes.

SlBL4 regulates the auxin gradient in the pedicel and affects the expression of auxin transport-related genes

Several studies have found that auxin plays a critical role in pedicel abscission via continuous flow from flowers or fruit3,8,10,43. Our results demonstrated that silencing SlBL4 affects the formation of pedicels in tomato plants. The IAA content in the RNAi lines was less than that in the WT plants (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, IAA treatments were performed on the seeding and floral pedicel AZs to show their effects on the abscission process. The results showed that the explants began to abscise at 8 h in the RNAi lines not treated with IAA (Fig. 2D), but they began to abscise at 24 h in the RNAi lines treated with IAA. Compared with this, the explants began to abscise at 16 h in the WT plants not treated with IAA (Fig. 2E). The root growth phenotype also indicated that the RNAi lines were more sensitive to IAA treatment than the WT plants (Fig. 2J and K). All of the above results demonstrated that IAA could postpone AZ abscission and that knockdown of SlBL4 could cause an early abscission phenotype by reducing the accumulation of IAA. At the break stage, the fruit began to drop, and the auxin contents were reduced in the AZs of the SlBL4 RNAi lines compared with the WT plants, suggesting that SlBL4 plays a role in modulating auxin levels (Figs. 4 and 7). The effect of IAA-related gene expression can also help clarify which genes are likely to directly or indirectly participate in the abscission process. SlPIN1 plays an important role in regulating not only the basipetal auxin flux from the seed to the plant but also the fruit to the basal organ3,45–47. Silencing the expression of SlPIN1 decreases the auxin content in the AZ, which is necessary for preventing tomato pedicel abscission46. In A. thaliana, LAX3 has been shown to actively regulate auxin influx48,49. LAX3, which is an ortholog of AtLAX3, plays a role in the regulation of auxin influx in the tomato pericarp47. SlPIN1 and LAX3 were downregulated by 3.08- and 0.34-fold, respectively, in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage (Table 1). Our results also indicated that SlBL4 directly activated the expression of the auxin efflux transporter genes SlPIN1 and LAX3, thus accounting for the lower auxin content in the SlBL4 RNAi plant pedicel (Figs. 6–7). ARF7 and ARF19 are involved in abscission in A. thaliana50, and the expression of SlARF19 is upregulated in flower AZs (FAZs)51. The expression level of ARF9 homolog (ARF9A) was shown to be significantly higher in the proximal region than in AZs and distal regions10. Our transcriptomic results showed that the transcript abundances of three auxin response genes (ARFs; ARF7B, ARF9A, or ARF19) were downregulated in the RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage (Table 1). Constant auxin flux plays an important role in preventing abscission1. SlPIN9 and PIN-like 3 were downregulated in the FAZs of KD1 antisense tomato plants, which suggested that the KD1 gene plays a role in manipulating auxin levels by altering the expression of auxin efflux transporters33. The SlPIN3, SlPIN5, SlPIN6, and SlPIN7 genes were highly expressed in FAZs52. Five PIN genes (SlPIN1, SlPIN-LIKES 3, SlPIN5, SlPIN6, and SlPIN7) and two LAX genes (LAX2 and LAX3) were downregulated in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage (Table 1), indicating a complex interplay among different components (AUX/IAA, ARFs, PIN, and LAXs) of the auxin response pathway during tomato pedicel abscission. These results were consistent with our hypothesis that SlBL4 plays a role in manipulating auxin levels in the AZ, perhaps by regulating transport genes for auxin influx and efflux. The timing of pedicel abscission was determined by the auxin level43. Therefore, SlBL4 may be involved in the timing of abscission onset by regulating the expression of ARFs, auxin influx, and efflux transport genes.

The SlBL4 gene suppresses cell wall hydrolytic enzymes in tomato pedicles

The last step of abscission is an activation of cell wall-degrading enzymes such as PG, Cel, XTH, and EXP and subsequent removal of plant organs43–61. In our study, 8 polygalacturonase, 5 Cel, 10 XTH, 10 EXP, and 1 peroxidase gene were upregulated in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plants at the abscission stage (Table 1). Silencing of PGs delayed abscission in tomato62. PG1 was highly expressed in flower AZs, and its expression was inhibited by auxin63,64. Cel1 and Cel2 play important roles in tomato flower and leaf abscission53,65. In our previous study, we showed that SlPE expression was regulated by SlBL4, that the transcription of SlPE was directly repressed by SlBL4, and that such actions were involved in pectin depolymerization29. The expression of SlPE was also increased in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage, which suggested that SlPE is also involved in cell wall modification and cell separation during pedicel abscission in tomato. Expansins (EXPs) are involved in the cell wall and pectin modification during the abscission process66–70. Expansins also reportedly regulate pedicel abscission in A. thaliana and soybean (Glycine max L.) and leaflet abscission in elderberry (Sambucus nigra), tomato, and citrus (Citrus L.)52,60,66,68,71. We observed that the expression levels of several EXP genes, such as EXPA45 or EXPB1, were significantly upregulated in the SlBL4 RNAi line compared with the WT plant at the abscission stage.

In conclusion, SlBL4 plays a role in establishing and maintaining the properties of pre-abscission tomato pedicel AZs by regulating shoot meristem genes, auxin influx, and efflux transport genes and cell wall hydrolytic genes. The results of this study provide insight into a new aspect of the regulation of organ development and abscission by BELL family proteins with regard to tomato pedicel formation.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31601763 and 31972470) and the Inner Mongolia University High-Level Talent Research Program (12000-15031934).

Author contributions

F.Y. performed most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Z.H.G., J.G.H., and Z.Q. helped to perform the dual-luciferase transient expression assays and analyze the data. X.S.M., R.N.Y., and R.Y.B. cultivated the tomato plants and performed the qPCR experiments. W.D. revised the manuscript. H.W. and Z.G.L. conceived the research and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Zhengguo Li, Email: zhengguoli@cqu.edu.cn.

Hada Wuriyanghan, Email: nmhadawu77@imu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41438-021-00515-0.

References

- 1.Roberts JA, Elliott KA, Gonzalez-Carranza ZH. Abscission, dehiscence, and other cell separation processes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002;53:131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.092701.180236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addicot, F. T. Abscission (University of California Press, 1982).

- 3.Taylor JE, Whitelaw CA. Signals in abscission. N. Phytologist. 2001;151:323–339. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646x.2001.00194.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleecker AB, Patterson SE. Last exit: senescence, abscission, and meristem arrest in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1169–1179. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McManus MT. Further examination of abscission zone cells as ethylene target cells in higherplants. Ann. Bot. 2008;101:285–292. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meir S, et al. Identification of defense-related genes newly-associated with tomato flower abscission. Plant SignaBehavior. 2011;6:590–593. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.4.15043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, et al. Transcriptome analysis of tomato flower pedicel tissues reveal abscission zone-specific modulation of key meristem activity genes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts JA, Elliott KA, Gonzalez-Carranza ZH. Abscission, dehiscence, andother cell separation processes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002;53:131–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.092701.180236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estornell LH, Agustí J, Merelo P, Talón M, Tadeo FR. Elucidating mechanisms underlying organ abscission. Plant Sci. 2013;199-200:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano T, Fujisawa M, Shima Y, Ito Y. Expression profiling of tomato pre-abscission pedicels provides insights into abscission zone properties including competence to respond to abscission signals. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lashbrook CC, Tieman DM, Klee HJ. Differential regulation of the tomato ETR gene family throughout plant development. Plant J. 1998;15:243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao L, et al. JOINTLESS is a MADS-box gene controlling tomato flower abscission zone development. Nature. 2000;406:910–913. doi: 10.1038/35022611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budiman MA, et al. Localization of jointless-2 gene in the centromeric region of tomato chromosome 12 based on high resolution genetic and physical mapping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;108:190–196. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano T, et al. MACROCALYX and JOINTLESS interact in the transcriptional regulation of tomato fruit abscission zone development. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:439–450. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, et al. The sepallata mads-box protein slmbp21 forms protein complexes with jointless and macrocalyx as a transcription activator for development of the tomato flower abscission zone. Plant J. 2014;77:284–296. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szymkowiak EJ, Irish EE. JOINTLESS suppresses sympodial identity in inflorescence meristems of tomato. Planta. 2006;223:646–658. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinet M, Kinet JM, Lutts S. Flowering response of the uniflora: blind:self-pruning and jointless: uniflora: self-pruning tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) triple mutants. Physiologia Plant. 2011;141:166–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schumacher K, Schmitt T, Rossberg M, Schmitz G, Theres K. The Lateral suppressor (Ls) gene of tomato encodes a new member of the VHIID protein family. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:290–295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mc Kim SM, et al. The BLADE-ON-PETIOLE genes are essential for abscission zone formation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2008;135:1537–1546. doi: 10.1242/dev.012807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bürglin TR. Analysis of TALE superclass homeobox genes (MEIS, PBC, KNOX, Iroquois, TGIF) reveals a novel domain conserved between plants and animals. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4173–4180. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douglas SJ, Chuck G, Dengler RE, Pelecanda L, Riggs CD. KNAT1 and ERECTA regulate inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:547–558. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venglat SP, et al. The homeobox gene BREVIPEDICELLUS is a key regulator of inflorescence architecture in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4730–4735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072626099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ragni L, Belles-Boix E, Gunl M, Pautot V. Interaction of KNAT6 and KNAT2 with BREVIPEDICELLUS and PENNYWISE in Arabidopsis inflorescences. Plant Cell. 2008;20:888–900. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Pi L, Huang H, Xu L. ATH1 and KNAT2 proteins act together in regulation of plant inflorescence architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:1423–1433. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrne ME. Phyllotactic pattern and stem cell fate are determined by the Arabidopsis homeobox gene BELLRINGER. Development. 2003;130:3941. doi: 10.1242/dev.00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith HM, Hake S. The interaction of two homeobox genes, BREVIPEDICELLUS and PENNYWISE, regulates internode patterning in the Arabidopsis inflorescence. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1717–1727. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith HM, Campbell BC, Hake S. Competence to re spond to floral inductive signals requires the homeobox genes PENNYWISE and POUND-FOOLISH. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhatt AM, Etchells JP, Canales C, Lagodienko A, Dick inson H. VAAMANA-a BEL1-like homeodomain protein, interacts with KNOX proteins BP and STM and regulates inflorescence stem growth in Arabidopsis. Gene. 2004;328:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan F, et al. SlBL4 regulates chlorophyll accumulation, chloroplast development and cell wall metabolism in tomato fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2020;71:5549–5561. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng W, et al. The tomato SlIAA15 is involved in trichome formation and axillary shoot development. N. Phytologist. 2012;194:379–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fillatti JJ, Kiser J, Rose R, Comai L. Efficient transfer of aglyphosate tolerance gene into tomato using a binary Agrobacterium tumefaciens vector. Nat. Biotechnol. 1987;5:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nbt0787-726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan Fang, et al. Ectopic expression a tomato KNOX Gene Tkn4 affects the formation and the differentiation of meristems and vasculature. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015;89:589–605. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma C, et al. A knotted1-like homeobox protein regulates abscission in tomato by modulating the auxin pathway. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:844–853. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.253815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry CS, et al. Altered chloroplast development and delayed fruit ripening caused by mutations in a zinc metalloprotease at the lutescent2 locus of tomato. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1086–1098. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.197483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellens RP, et al. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods. 2005;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sexton R, Roberts JA. Cell biology of abscission. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1982;33:133–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.33.060182.001025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay A, Tsiantis M. KNOX genes: versatile regulators of plant development and diversity. Development. 2010;137:3153–3165. doi: 10.1242/dev.030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanhuan Meng, et al. 2018. BEL1-LIKE HOMEODOMAIN 11 regulates chloroplast development and chlorophyll synthesis in tomato fruit. Plant J. 2018;94:1126–1140. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson SE. Cutting loose Abscission and dehiscence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:494–500. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer KF, et al. Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell. 1998;95:805–815. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller D, Schmitz G, Theres K. Blind homologous R2R3 Myb genes control the pattern of lateral meristem initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:586–597. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raman S, et al. Interplay of miR164, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes and LATERAL SUPPRESSOR controls axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008;55:65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meir S, et al. Microarray analysis of the abscission-related transcriptome in the tomato flower abscission zone in response to auxin depletion. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1929–1956. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.160697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitz G, et al. The tomato Blind gene encodes a MYB transcription factor that controls the formation of lateral meristems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1064–1069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022516199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manojit MB, et al. The manipulation of auxin in the abscission zone cells of Arabidopsis flowers reveals that indoleacetic acid signaling is a prerequisite for organ shedding. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:96–106. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.216234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi Z, et al. SlPIN1 regulates auxin efflux to affect flower abscission process. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:14919. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15072-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pattison RJ, Carmen C. Evaluating auxin distribution in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) through an analysis of the PIN and AUX/LAX gene families. Plant J. 2012;70:4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swarup K, et al. The auxin influx carrier LAX3 promotes lateral root emergence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:946–954. doi: 10.1038/ncb1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandenbussche F, et al. The auxin influx carriers AUX1 and LAX3 are involved in auxin-ethylene interactions during apical hook development in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Development. 2010;137:597–606. doi: 10.1242/dev.040790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellis CM, et al. Auxin Response Factor1 and Auxin Response Factor 2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2005;132:4563–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guan X, et al. Temporal and spatial distribution of auxin response factor genes during tomato flower abscission. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014;33:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s00344-013-9377-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srivignesh S, et al. (2016). De novo transcriptome sequencing and development of abscission zone-specific microarray as a new molecular tool for analysis of tomato organ abscission. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;6:1258. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lashbrook CC, Gonzalez-Bosch C, Bennett AB. Two divergent indo-b-1,4-glucanase genes exhibit overlapping expression in ripening fruit and abscising flowers. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1485–1493. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalaitzis P, Solomos T, Tucker ML. Three different polygalacturonases are expressed in tomato leaf and flower abscission, each with a different temporal expression pattern. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:1303–1308. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lashbrook CC, Giovannoni JJ, Hall BD, Fisher RL, Bennett AB. Transgenic analysis of tomato endo-b-1,4-glucanase gene function: role of Cel1 in floral abscission. Plant J. 1998;13:303–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00025.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agustı´ J, Merelo P, Cerco´s M, Tadeo FR, Talo´n M. Ethylene-induced differential gene expression during abscission of citrus leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:2717–2733. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agustı´ J, et al. Comparative transcriptional survey between laser-microdissected cells from laminar abscission zone and petiolar cortical tissue during ethylene-promoted abscission in citrus leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts JA, Gonzalez-Carranza ZH. Pectinase function in abscission. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2009;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim J. Four shades of detachment: regulation of floral organ abscission. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e976154. doi: 10.4161/15592324.2014.976154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merelo Paz, et al. Cell wall remodeling in abscission zone cells during ethylene-promoted fruit abscission in citrus. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:126. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Song L, Valliyodan B, Prince S, Wan J, Nguyen H. Characterization of the XTH gene family: new insight to the roles in soybean flooding tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2705. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang CZ, Lu F, Imsabai W, Meir S, Reid MS. Silencing polygalacturonase expression inhibits tomato petiole abscission. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:973–979. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalaitzis P, Koehler SM, Tucker ML. Cloning of a tomato polygalacturonase expressed in abscission. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995;28:647–656. doi: 10.1007/BF00021190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hong SB, Sexton R, Tucker ML. Analysis of gene promoters for two tomato polygalacturonases expressed in abscission zones and the stigma. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:869–881. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brummell DA, Hall BD, Bennett AB. Antisense suppression of tomato endo-1,4-beta-glucanase Cel2 mRNA accumulation increases the force required to break fruit abscission zones but does not affect fruit softening. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;40:615–622. doi: 10.1023/A:1006269031452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cho H-T, Cosgrove DJ. Altered expression of expansin modulates leaf growth and pedicel abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9783–9788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160276997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee Y, Choi D, Kende H. Expansins: ever-expanding numbers and functions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2001;4:527–532. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cosgrove DJ, et al. The growing world of expansins. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:1436–1444. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Belfield EJ, Ruperti B, Roberts JA, McQueen-Mason S. Changes in expansion activity and gene expression during ethylene-promoted leaflet abscission in Sambucus nigra. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;56:817–823. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim J, et al. Examination of the abscission-associated transcriptomes for soybean, tomato and Arabidopsis highlights the conserved biosynthesis of an extensible extracellular matrix and boundary layer. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1109. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tucker ML, Burke A, Murphy CA, Thai VK, Ehrenfried ML. Gene expression profiles for cell wall-modifying proteins associated with soybean cyst nematode infection, petiole abscission, root tips, flowers, apical buds, and leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:3395–3406. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.