Abstract

Here, we addressed the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic organoselenium compounds and some naturally occurring organoselenium amino acids. The use of selenium as a tool in organic synthesis and as a pharmacological agent goes back to the middle of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries. The rediscovery of ebselen and its investigation in clinical trials have motivated the search for new organoselenium molecules with pharmacological properties. Although ebselen and diselenides have some overlapping pharmacological properties, their molecular targets are not identical. However, they have similar anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, possibly, via activation of transcription factors, regulating the expression of antioxidant genes. In short, our knowledge about the pharmacological properties of simple organoselenium compounds is still elusive. However, contrary to our early expectations that they could imitate selenoproteins, organoselenium compounds seem to have non-specific modulatory activation of antioxidant pathways and specific inhibitory effects in some thiol-containing proteins. The thiol-oxidizing properties of organoselenium compounds are considered the molecular basis of their chronic toxicity; however, the acute use of organoselenium compounds as inhibitors of specific thiol-containing enzymes can be of therapeutic significance. In summary, the outcomes of the clinical trials of ebselen as a mimetic of lithium or as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 proteases will be important to the field of organoselenium synthesis. The development of computational techniques that could predict rational modifications in the structure of organoselenium compounds to increase their specificity is required to construct a library of thiol-modifying agents with selectivity toward specific target proteins.

Keywords: Ebselen, Selenium, Diselenides, Toxicology, Pharmacology, Thiol

Introduction

In this review, we shall cover toxicological and pharmacological effects, in which organoselenium compounds are involved, but the effects of inorganic compounds will not be addressed here. The review mostly discusses recent literature, starting from 2011 until the end of 2020; however, some earlier studies are cited when needed. Method data for this review were sourced from online Web of Science database. The deadline for data search was August 2020; no data were excluded based on language or publication origin. Since, it is not possible to cite all of the findings that have taken place, we apologize to those whose work has been omitted.

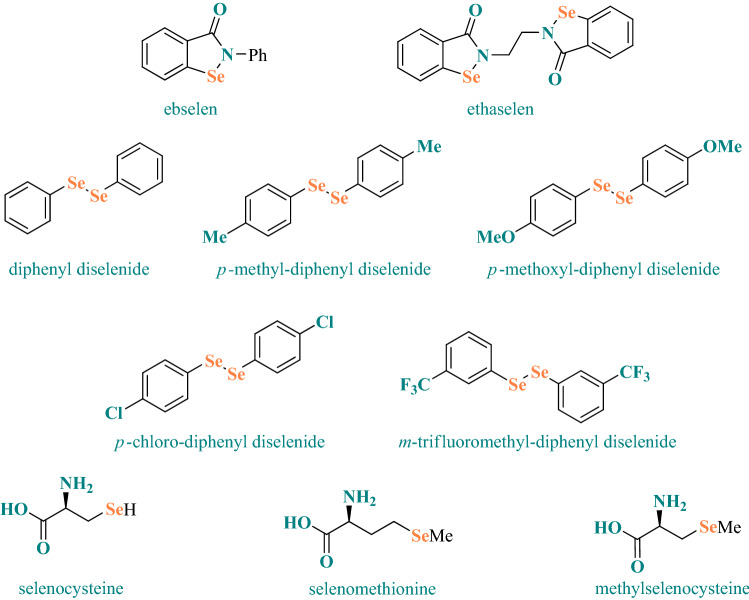

The chemical structures of representative organoselenium compounds which will be discussed in this review are shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures of representative organoselenium compounds discussed in this review

A brief history of selenium: an element with two faces

Since its discovery about 200 years ago, selenium has been attracting the interest of chemists and biologists. Soon after its isolation by Jacobs Berzelius, in 1817, selenium was used in organic synthesis and investigated as a potentially toxic or beneficial agent both in animals (including humans) and plants (Levine 1915, 1925; Martin 1936; Rocha et al. 2017; Smith 1941; Weil 1915). One of the first therapeutic uses of selenium was in the treatment of cancer and reports about the beneficial effects of elemental selenium in the treatment of inoperable carcinoma can be found in clinical studies published at the beginning of the twentieth century (Freeman 1922; Watson-Williams 1919; Weil 1915). In sharp contrast, the lethal effect of a single injection of selenite in one human patient with cancer can also be found in the literature, cited in Weil (1915). Subsequently, selenium was rarely used in cancer treatment in humans, possibly because its effectiveness in clinical studies was inconsistent (Weil 1915). In addition, the toxicity of selenium became notorious in farm and experimental animals exposed to high levels of the element (Levine 1915, 1925; Painter 1941; Smith 1941). In short, the early history of the element selenium in biology has been marked by the contrast between its toxic and beneficial effects.

The importance of selenium to mammals started to be defined in 1957 when Schwartz and Foltz demonstrated that selenite and selenate could prevent liver necrosis caused by feeding a vitamin E-deficient diet to rats. Though the classical paper of Schwartz and Foltz did not establish dietary essentiality to selenium in rats, it gave the first demonstration that selenium could mitigate the deficiency of an essential vitamin (Schwarz and Foltz 1957). The explanation on how vitamin E and selenium have partial overlapping nutritional and biochemical protective effects in mammals was deciphered only in 1985, when the phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (GPx4) was characterized as a selenium enzyme (Ursini et al. 1985). GPx4 is involved in the degradation of phospholipid hydroperoxides in biomembranes of mammalian cells, and consequently, it protects cell membranes from lipid peroxidation up-stream to vitamin E. Vitamin E scavenges phospholipid hydroperoxyl radicals directly, whereas GPx4 decreases the concentration of phospholipid peroxides that can generate the reactive peroxyl radicals. It is noteworthy that the selenium atom of the selenol (–SeH) group of GPx4 interacts directly with lipid peroxides in biomembranes, whereas vitamin E interacts with lipid peroxide radicals.

The first discovered biochemical role of selenium was its presence as an integral part of the enzyme glutathione peroxidase (Flohe et al. 1973; Rotruck et al. 1973). The accurate molecular role played by selenium in mammalian cell biochemistry was elucidated in 1978, when the chemical nature of selenium, in the active site of rat liver glutathione peroxidase, was deciphered (Forstrom et al. 1978). The studies of Cone with bacteria (Cone et al. 1976) and Forstrom with rodents (Forstrom et al. 1978) introduced in the chemistry of life a new amino acid and a new functional group: the selenocysteine and the selenol group. They are analogs of the amino acid cysteine and its functional thiol group. The essentiality of selenocysteine and its selenol group in the biochemistry and physiology of mammalian cells will be presented in the next section: selenium physiology: selenium as a component of selenoproteins.

Adequate selenium intake has also been indicated to be critical to proper immune function and decrease the risk of cardiovascular diseases (Avery and Hoffmann 2018; Huang et al. 2012; Kuria et al. 2020; Qian et al. 2019; Rayman 2012). Furthermore, beneficial effects of appropriate blood selenium levels as a factor against virus infections (particularly HIV and, more, recently against SARS-CoV-2) and sepsis severity have also frequently appeared in the literature (Aggarwal et al. 2016; Alhazzani et al. 2013; Guillin et al. 2019; Heller et al. 2020; Mertens et al. 2015; Moghaddam et al. 2020; Rayman 2012; Zhang et al. 2020b, c). However, negative and contradictory results can also be found in the literature (Bloos et al. 2016; Kamwesiga et al. 2015; Shivakoti et al. 2014; Stone et al. 2010). However, it is still elusive if selenium has specific direct role in such complex physiological, immunological, and pathological responses or if selenoproteins modulate indirectly the inflammatory and other responses by modulating the redox state of the body.

The influence of selenium supplementation as a potential anticarcinogenic agent was studied in a large epidemiological study in USA. The SELECT study compared the supplementation of selenium (as selenomethionine) and vitamin E in the incidence of prostate cancer. However, the study was interrupted before planned, because the data, contrary to the expectation, have not indicated potential beneficial effects of selenium or vitamin E. Despite the negative outcomes of SELECT (Dunn et al. 2010; Klein et al. 2011; Lippman et al. 2009; Nicastro and Dunn 2013), the potential use of selenium in cancer prevention or treatment is still a matter of debate (Chapelle et al. 2020; Vinceti et al. 2018). Several experimental studies have indicated the potential anti-cancer properties of inorganic and organic forms of selenium (Álvarez-Pérez et al. 2018; Gandin et al. 2018; Gopalakrishna et al. 2018; Krasowska et al. 2019; Ruberte et al. 2019; Sanmartín et al. 2012; Sharma and Amin 2013; Spengler et al. 2019; Steinbrenner et al. 2013; Tan et al. 2019). Some clinical studies have also demonstrated that selenite can have beneficial effects by itself or decrease some toxic effects of radiotherapy in cancer patients (Brodin et al. 2015; Han et al. 2019; Handa et al. 2020; Knox et al. 2019; Muecke et al. 2014). More recently, ethaselen (a derivative of ebselen) was described to have pharmacological effects against lung cancer cell lines and is now recruiting patients for clinical trials for lung cancer treatment (Tan et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2017b).

The supranutritional intake of selenium has been linked with increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, advanced prostate cancer, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and neurodegenerative diseases (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), early onset dementia, and Parkinson Disease) (Adani et al. 2020a, b; Bastola et al. 2020; Loomba et al. 2020; Vinceti et al. 2018, 2019a, b; Wu et al. 2018; Yarmolinsky et al. 2018). In accordance with epidemiological studies, the intake of supranutritional levels of selenium, which were associated with an overexpression of two selenoenzymes [glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1) and methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrB1)] has been shown to cause hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in mice (Labunskyy et al. 2011). The detrimental effects of selenium in glucose homeostasis have been attributed to deregulation of cell redox balance (reductive stress). In contrast, the insufficient synthesis of selenoproteins by overexpressing a mutant selenocysteine t-RNA caused glucose intolerance and diabetes-like phenotype in mice (Labunskyy et al. 2011).

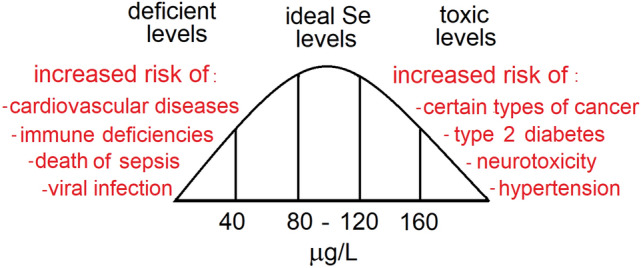

Concerning ALS, it seems that the speciation of selenium (e.g., selenite or selenate vs organic forms) can determine the neurotoxicity of selenium in humans (Vinceti et al. 2019b). Accordingly, Vicenti and collaborators have recently demonstrated that the speciation of selenium in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with mild cognitive deficits predicted the risk of progression to Alzheimer's disease, with selenate (Se+6) increasing the risk significantly (Vinceti et al. 2017). Thus, in relation to cancer and other degenerative diseases, the role of selenium seems to have a U inverted shape curve with a relatively narrow range of selenium for the optimum physiological effects (Fig. 1). Another point that is highly critical and little explored is the speciation of selenium as a determinant of its toxic effects. Of particular toxicological importance, recent data have indicated that high levels of cationic selenium (e.g., selenate) in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with mild cognitive impairment increases the risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease (Vinceti et al. 2017).

Fig. 1.

U inverted shaped curve for selenium levels in humans. Low selenium status can increase the risk of immunological malfunctioning, cardiovascular diseases, sepsis severity, virus infection, and cognitive deficits. High levels of blood selenium can be associated with an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer (e.g., melanoma and prostate cancer), hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., ALS and Alzheimer's Dementia). In the figure, the ideal levels of selenium were arbitrarily based on the optimal blood activity of glutathione peroxidase (see below). Selenium plays important physiological functions as a part of 25 selenoproteins in humans. At least one half of them are important oxireductases (e.g., 5 glutathione peroxidases (GPxs1-4 and 6); 3 thioredoxin reductases (TrxRs), which are involved in the regeneration of reduced thioredoxin (Trx); methionine sulfoxide reductase, which reduces oxidized methionine sulfoxide to methionine in proteins, 3 deiodinases (DIOs) that are involved in the metabolism of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4); selenophosphate synthetase and several selenoproteins without a clear-defined molecular role in cell physiology. The ideal physiological levels of selenium are not known, but for the blood GPx maximal activity, a level of selenium around 100 µg L−1 is required (Rea et al. 1979; Thomson et al. 1977, 1982). However, how blood GPx activity can predict the whole-body selenoproteins adequate physiological activity is unknown. There is also epidemiological evidence, suggesting that above 120 μg L−1, selenium can start to facilitate the installation of pathological conditions (Bastola et al. 2020)

In this review, we will emphasize the potential pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic organoselenium compounds and some naturally occurring organoselenium amino acids (e.g., selenomethionine). The use of selenium as an important tool in organic synthesis and as a pharmacological agent goes back to the middle of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries. Notably, the rediscovery of ebselen (which was originally synthesized in 1924) and its investigation in several clinical trials in different types of human pathologies have motivated the search for new selenium-containing molecules with pharmacological properties (Masaki et al. 2016a; Ogawa et al. 1999; Saito et al. 1998; Singh et al. 2016; Yamaguchi et al. 1998). One point that has further stimulated the search for novel organoselenium compounds is the successive failures of ebselen or its low effectiveness as therapeutic agent (Beckman et al. 2016; Kil et al. 2017; Masaki et al. 2016a; Ogawa et al. 1999; Saito et al. 1998; Yamaguchi et al. 1998).

However, here, we have to emphasize that ebselen is still under clinical trials to treat bipolar disorder (Sharpley et al. 2020a) and has been registered for two clinical trials with moderate and severe COVID-19 patients (Haritha et al. 2020). Besides, ethaselen, an ebselen derivative, is in the recruiting phase of a clinical trial to treat lung cancer. The compound has been effective in a pre-clinical trial in human non-small cell lung cancer models (Ye et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2017b,2019b). In short, though ebselen has not been approved to treat a specific disease, its safety in humans has been an indication that organoselenium compounds can be promising therapeutic agents.

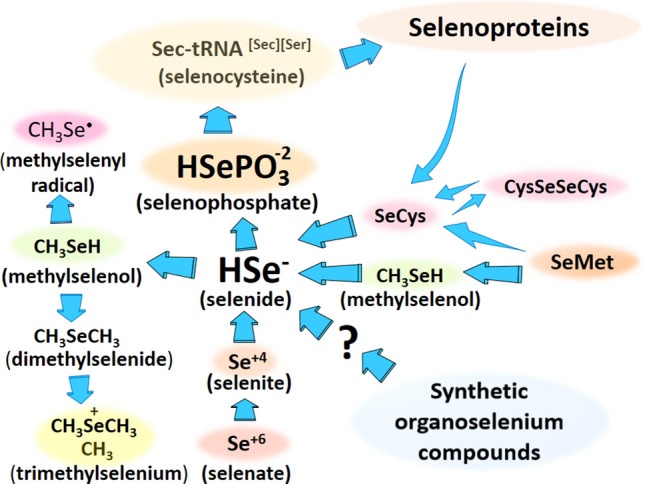

Physiological chemistry of selenium: selenium as component of selenoproteins

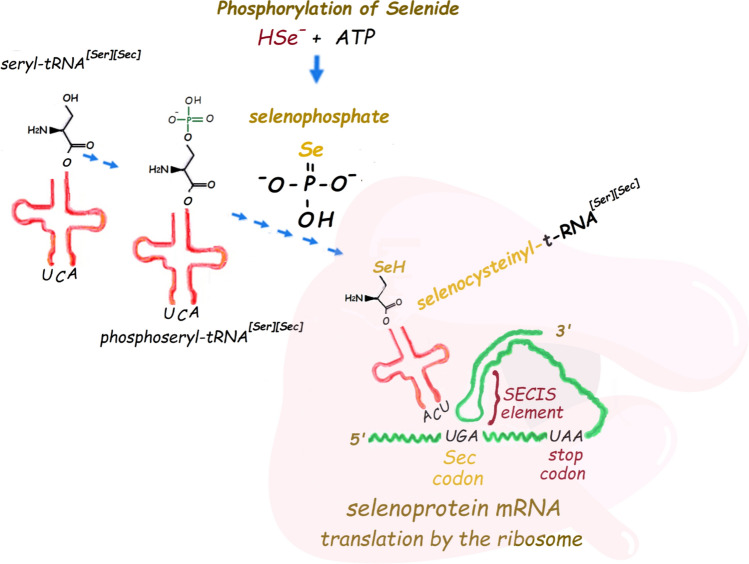

The physiological chemistry of selenium in animals is played almost exclusively by the selenocysteinyl residue(s) found in a few types of selenoproteins. Selenocysteine is an analogue of cysteine and serine. The human genome codifies 25 selenoproteins that have usually only one residue of selenocysteine (Sec); the exception is the selenoprotein P that has near 10 s residues (for a brief description of selenoproteins function, see the legend of Fig. 1). The incorporation of selenium into the seryl-carbon skeleton is complex and occurs at the level of the transfer RNA (t-RNA[Ser]Sec) (in a process named co-translational incorporation of Sec in its t-RNA and then in the selenoproteins) (for reviews, see Hatfield et al. 2014; Labunskyy et al. 2014). This t-RNA[Ser]Sec is first loaded with a seryl residue by the action of a seryl t-RNA synthetase and metabolized to phosphoseryl-t-RNA[Ser]Sec by the enzyme seryl–t-RNA[Ser][Sec] kinase (PSTK). Then, selenophosphate donates, via the reaction catalyzed by the enzyme selenocysteine synthase (SepSecS), the selenium atom to form the selenol group in the place of the phosphorylated OH group of serine (Fig. 2). The incorporation of the selenium atom in an organic moiety requires four enzymatic steps, including the binding of serine to the t-RNA[Ser]Sec, the phosphorylation of loaded seryl residue, the synthesis of selenophosphate by the reaction of HSe- (selenide) with ATP (a reaction catalyzed by the selonoenzyme selenophosphate synthetase), and the incorporation of selenophosphate in the place of the phosphorylated OH group of serine. For details about the incorporation of selenium in the serine skeleton, see the reviews (Hatfield et al. 2014; Labunskyy et al. 2014; Serrão et al. 2018).

Fig. 2.

Incorporation of selenide in the phosphoseryl-t-RNA[Ser]Sec and synthesis of selenocysteinyl-t-RNA[Ser]Sec after the reaction of selenophosphate with the phosphorylated hydroxyl group of serine-loaded t-RNA[Ser]Sec. Selenocysteine is released from the t-RNA when the ribosome reads the UGA codon inside the mRNA sequence of a selenoprotein. The recoding of UGA codon to selenocysteine depends on the SECIS elements (which in mammals is a non-coding mRNA forming a stem-loop structure that kinks to interact with the t-RNA). The translation of the in-frame UGA codons inside the genes of selenoproteins also requires several protein factors that are not indicated in the figure (for more details, consult the text or the reviews Bulteau and Chavatte 2015; Howard and Copeland 2019; Simonović and Puppala 2018)

The entire process requires several steps, protein factors, e.g., the Sec-t-RNA[Ser]Sec dedicated translation elongation factor (EFSec), SECIS-binding protein 2 (SBP2 or SECISBP2), ribosomal protein eL30, translation initiation factor 4A3 (eIF4A3), nucleolin, Secp43 or t-RNA selenocysteine 1-associated protein 1 (TRNAU1AP) and SepSecS), the specific RNA sequences (the selenocysteine insertion sequence or SECIS elements), and the t-RNA[Ser]Sec. The machinery utilized in the synthesis of selenoproteins interprets the stop codon UGA as selenocysteine only when it is present within the RNA sequences of the selenoproteins. The key players here are the SECIS elements, which in vertebrates are non-codifying RNA regions adjacent to the selenoprotein sequence, and selenocysteine-t-RNA (Bulteau and Chavatte 2015; Howard and Copeland 2019; Serrão et al. 2018; Simonović and Puppala 2018).

As briefly commented in the previous paragraph, the existence of these SECIS elements forming a stem-loop-stem-loop structure with near 100 nucleotides in the 3′-untranslated region of human 25 selenoprotein mRNAs is indispensable for the proper insertion of Sec in the selenoproteins. In fact, the stem–loop–stem–loop forming the SECIS bends or kinks itself toward the UGA codon inside the selenoprotein sequence and, inside of the ribosome, SECIS interacts with the t-RNA loaded with Sec and with protein factors described just above, allowing the release of the transporter and the incorporation of selenocysteine in the nascent polypeptide. For reviews about the molecular players in the noncanonical incorporation of Sec at UGA codon in selenoproteins (i.e., about the recoding of UGA), see (Bulteau and Chavatte 2015; Howard and Copeland 2019; Simonović and Puppala 2018). The selenocysteinyl residue, specifically its selenol group, is the softest of the nucleophile centers found in biomolecules. Accordingly, several selenoproteins are oxidoreductases enzymes, where the -SeH (-Se−) of the selenocysteine participates in the catalysis. The well-characterized selenoproteins include glutathione peroxidase isoforms (e.g., GPx1 and GPx4); thioredoxin reductase isoforms (TrxR1, TrxR2, TrxR3), iodothyronine deiodinases (DIO1, DIO2, and DIO3), methionine sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB), selenophosphate synthetase, and selenoprotein P. There are a group of endoplasmatic reticulum-resident selenoproteins which the molecular roles are still elusive (Pitts and Hoffmann 2018; Addinsall et al. 2018; Gennadyevna 2020; Pitts and Hoffmann 2018). In addition to DIO2, selenoproteins K, M, N, S, T, and selenoprotein 15 kDa are found in the endoplasmic reticulum, where they appear to be involved in the regulation of Ca2+ levels, protein folding, inflammatory processes, and oxidative stress (Addinsall et al. 2018; Gennadyevna 2020; Pitts and Hoffmann 2018; Pothion et al. 2020; Shchedrina et al. 2010).

As commented above, the physiological chemistry of selenium seems to be played almost exclusively by the –SeH group of selenoproteins. Recently, it was demonstrated that selenocysteine can be incorporated in the uncoupling protein (UCP1) in the place of cysteine (Jedrychowski et al. 2020). The process is not a random incorporation of selenocysteine, but occurs in a specific cysteinyl residue (Cys253). The incorporation of selenocysteine is expected to occur via its t-RNA[Ser][Sec], because selenocysteine does not exist as a free amino acid in the presence of oxygen and water. However, the reasons why a cysteine codon can interact with the t-RNA[Ser][Sec] are unknown. Despite this, the data published by Jedrychowski and collaborators may open a new role for selenium as a modulator of the cysteine physiological function, via specific incorporation of selenocysteine in the place of specific cysteinyl residue in a small portion of synthesized thiol-containing proteins (for instance, for replacement of Cys 253 in UCP1, about 1.5% of this position was loaded with Sec) (Jedrychowski et al. 2020).

Toxicity of organoselenium compounds

Interaction of selenium with thiols

Herein, we will emphasize the biochemistry of interaction of organoselenium compounds with thiols from molecules of biological significance and their implications, without highlighting the pathophysiological processes associated with high levels of selenium. Among the organoselenium compounds, we will address primarily selenides and diselenides, such as ebselen, diphenyl diselenide, and some derivatives of them.

The molecular mechanisms involved in selenium toxicity are not completely elucidated; however, the interaction of inorganic and organic selenium with low- and high-molecular-weight thiols plays a central role in their toxicity. This evidence was first reported to inorganic forms, in which classical experiments showed the effectiveness of selenite in oxidizing sulfhydryl groups, producing disulfides and an unstable intermediary containing –S–Se–S– bonds (Ganther 1968; Painter 1941; Tsen and Tappel 1958). Afterward, studies demonstrated that the oxidation of thiols, such as glutathione (GSH) and cysteine, by selenite produced the radical superoxide (Seko et al. 1989; Spallholz 1994). To date, the oxidation of thiols has also been the basis to explain the toxicity of a variety of organoselenium compounds (Barbosa et al. 2017; Nogueira and Rocha 2011; Prigol et al. 2012) and mounting evidence has pointed out that reactive species (RS) formation contributes for the toxicity of many compounds (Nogueira and Rocha 2011; Prigol et al. 2012). In effect, the occurrence of oxidative stress and related phenomena has been highlighted in numerous in vitro and in vivo studies with organoselenium compounds. Interestingly, the increased production of RS accompanied by cell viability loss, DNA damage, and apoptosis are considered important pro-oxidant effects elicited by some organoselenium compounds against cancer cells, virus, and fungal pathogens (Álvarez-Pérez et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2020; Sies and Parnham 2020; Thangamani et al. 2017). It is important to mention here that the thiol oxidation may also subsidize the antioxidant effects of some selenium compounds via activation of antioxidant gene expression.

Therefore, the systematic study of oxidation of sulfhydryl groups from biological thiol-containing molecules by organoselenium compounds has facilitated the identification of potential “molecular targets" that might support both selenium pro-oxidative and antioxidant effects. In this context, we will cite here some in vitro and in silico (computational) studies toward specific interactions of some organoselenium compounds with proteins containing vicinal thiol groups, which are more efficiently oxidized than monothiol molecules.

In vitro molecular toxicity of organoselenium compounds

Although the molecular mechanisms involved in toxicity of organoselenium compounds are still not completely understood, the interaction with thiols is pointed out as a key phenomenon. Similar to inorganic selenium molecules, the interaction of the sulfur atom from thiols with the selenium atom from organoselenium compounds (S….Se) can lead to the formation of a selenenyl–sulfide bond (S–Se), an adduct able to impair the activity of sulfhydryl enzymes. In fact, the toxic effects of several selenides and diselenides have been related to their potential in disrupting the activity of thiol-containing enzymes via oxidation of cysteinyl residues (Barbosa et al. 1998; Chaudiere et al. 1992; Galant et al. 2017, 2020; Nogueira and Rocha 2011; Quispe et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2017).

Focusing on diphenyl diselenide and its derivatives, the more precise findings include mainly those toward the enzyme δ-aminolevulinate dehydratase (δ-ALA-D). δ-ALA-D catalyzes the condensation of two molecules of 5-aminolevulinic acid to porphobilinogen, a monopyrrol precursor of prosthetic group heme, and due to its sulfhydryl nature, it has been commonly used in toxicological researches as an indicator of toxicity caused by pro-oxidant agents (Chaudiere et al. 1992; Ecker et al. 2018; Klimaczewski et al. 2018; Rocha et al. 2012c).

The active site of δ-ALA-D possesses three cysteine residues coordinated with Zn2+, which prevent the formation of disulfide bridges between the sulfhydryl groups. The proximity of the cysteine groups in the active site renders to enzyme a high sensitivity to oxidation (Nogara et al. 2020; Rocha et al. 2012c; Saraiva et al. 2012).

The first studies demonstrating the diphenyl diselenide potential inhibitory on δ-ALAD were carried out comparing the animal and plant enzymes (Barbosa et al. 1998; Farina et al. 2002). These findings revealed that diphenyl diselenide inhibited the activity from the animal enzyme, but not from the plant, in which the active site has aspartic acid instead of cysteine residues and the metal Mg2+ in the place of Zn2+. Since that, various other diphenyl diselenide derivatives were reported as inhibitors of the enzyme from different sources, as well (Nogueira and Rocha 2011; Nogueira et al. 2004; Rocha et al. 2012a, b, c).

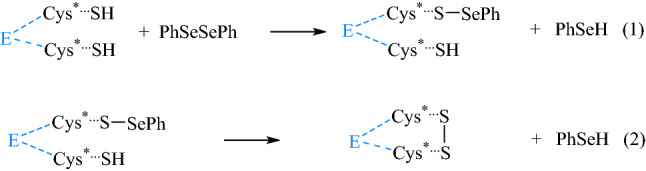

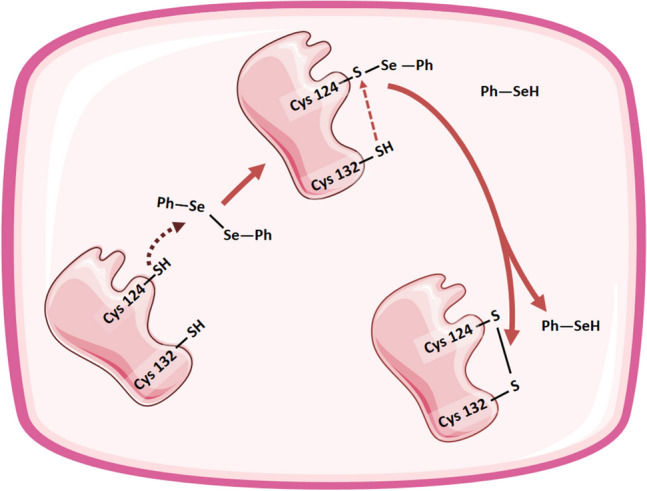

In general, the mechanism by which diphenyl diselenide and its derivatives inhibit the δ-ALA-D activity involves two steps of cysteine oxidation: (1) the first oxidation involves the attack of the selenium atom from diphenyl diselenide by the most reactive cysteinyl residue to yield the intermediate (E–S–SePh); and (2) the attack of the second more nucleophilic cysteinyl residue to the S–Se– bond of the intermediate (E–S–SePh), generating the oxidized enzyme (E–(S–S)) and two molecules of selenol (PhSeH) (Scheme 2) (Rocha et al. 2012c; Saraiva et al. 2012).

Scheme 2.

Molecular mechanism of oxidation of δ-ALAD catalytic thiols by diphenyl diselenide

By docking analyses, the cysteine 124 residue from the active site of the enzyme was identified as the nucleophilic center that initiates the attack on the Se–Se bond from diselenides, forming an E–S–SePh as intermediate. The vicinal cysteine 132 residue was identified as responsible for the subsequent attack to the S–Se bond, resulting in the formation of the disulfide bond between cysteines 124 and 132 from δ-ALA-D. Along with diphenyl diselenide, these interactions were also shown in silico for p-chloro, p-methoxy, and m-trifluoromethyl diselenide derivatives (Saraiva et al. 2012) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Additional proposed molecular mechanism showing the oxidation of catalytic cysteine (cys) 124 and 132 from human δ-ALAD by diphenyl diselenide, obtained by in silico studies (Nogara et al. 2020; Saraiva et al. 2012)

A very recent docking study was performed with sources of δ-ALA-D enzyme from Homo sapiens (Hsδ-AlaD), Drosophila melanogaster (Dmδ-AlaD), and Cucumis sativus (Csδ-AlaD), and the results corroborated the previous findings and provided more information about the mechanism of action (Nogara et al. 2020). Nogara and collaborators also reported the interaction of diphenyl diselenide with the cysteine residues from Hsδ-AlaD and Dmδ-AlaD, but not with Csδ-AlaD (a non-thiol protein). In the Hsδ-AlaD active site, they found that the selenium atoms of diphenyl diselenide interacted with the carboxylic group of aspartate 120 and the Zn2+ ion, besides the thiolate group from cysteine 124. In the Dmδ-AlaD, selenium atoms interacted with arginine 205, proline 212, phenylalanine 204, tyrosine 20, and arginine 217 via H bond, and with the cysteine 122. Interestingly, they found that the diphenyl diselenide putative metabolite, phenylseleninic acid, as well as other oxidized organoselenium forms presented similar binding pose, interacting with the cysteine 124 and 122 residues from the active site from Hsδ-AlaD and Dmδ-AlaD, respectively (Nogara et al. 2020).

Because organoselenium compounds are highly prone to suffer a nucleophilic attack by cysteinyl residues, the activity of other sulfhydryl enzymes has been usually carried out to test the in vitro pro-oxidant potential of novel organochalcogens. Among them, the enzymes Na+, K+ATPase and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) have been investigated (Chagas et al. 2013a; Kade et al. 2009; Lugokenski et al. 2011). In addition to diphenyl diselenide, herein, we highlighted the toxicological studies showing the inhibitory effects of ebselen, 4-(4-fluorophenylseleno)-3-phenylisoquinoline), chloro (4-(4-chlorophenylseleno)-3-phenylisoquinoline), trifluoro (4-(3-trifluoromethylphenylseleno)-3-phenylisoquinoline), and bis(phenylimidazoselenazolyl) diselenide on δ-ALA-D and Na+, K+ATPase activities from rat tissues (Chagas et al. 2015; Sampaio et al. 2017a).

Recently, the activities of both enzymes were also used for screening the toxicity of novel zidovudine (AZT)-based selenides on human erythrocytes. Among 5′-phenylseleno-, p-chloro-, p-methyl-AZT derivatives, the p-methyl substituted AZT-derivative was the least toxic and did not cause δ-ALA-D and Na+, K+ ATPase inhibition, thiol depletion, and eryptosis; whereas the 5′-phenylseleno- and p-chloro- derivatives inhibited both δ-ALA-D and Na+, K+ ATPase activities, causing thiol depletion, and eryptosis (Ecker et al. 2018).

Regarding the oxidation of thiols from low-molecular-weight compounds, increasing evidence indicates that the oxidation rate seems to be dependent on pH and independent of thiol group pKa. At pH 7.4, cysteine and dithiothreitol were more reactive with diphenyl diselenide, whereas 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid, GSH, and dimercaptosuccinic acid exhibited a low reactivity (Hassan and Rocha 2012).

Organoselenium compounds: thiol depletion, reactive species overproduction, and mitochondrial dysfunction

As mentioned before, some organoselenium compounds may exhibit strong electrophilic activity, forming selenenyl-sulfide bonds with the cysteinyl residues from non-protein and protein thiols. Therefore, the activity of several protein families, including antioxidant enzymes as well as the GSH cell levels can be affected, and represent one of the main mechanisms by which organoselenium compounds modulate a wide spectrum of related biological processes. Among them, we highlighted herein those associated with oxidative stress, in which thiol depletion, RS overproduction, DNA damage, and mitochondrial dysfunctions are usually pointed out as key end-points.

Although ebselen and diphenyl diselenide are well recognized as antioxidant active agents, both compounds may exacerbate the production of RS at relatively high concentrations in vitro. In a range from 10 to 50 μM, ebselen and diphenyl diselenide induced RS overproduction, accompanied by loss of viability, and DNA damage in human white cells (Bueno et al. 2018; Caeran Bueno et al. 2013). Similarly, ebselen caused an increase in RS levels, viability loss, -SH oxidation, and calcium dyshomeostasis in cultured astrocytes (Santofimia-Castano et al. 2013, 2016).

It is important to note that depletion of thiols accompanied by the increase in RS production has been suggested as possible mechanisms involved in the action of ebselen, diphenyl diselenide, and its derivatives against a diversity of fungal pathogens (Bueno Rosseti et al. 2014; Jaromin et al. 2018; Ngo et al. 2016; Rosseti et al. 2015; Thangamani et al. 2017).

In line with this, a study toward Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that the deleterious effects of diphenyl diselenide on growth, size, and membrane permeability were followed by a marked RS overproduction at the highest concentration tested (10 µM) (Galant et al. 2017). Diphenyl diselenide and its dicholesteroyl diselenide derivative were genotoxic and mutagenic to S. cerevisiae, and these effects were associated with oxidative damage, because N-acetylcysteine partially reversed the toxicity of these compounds (de Oliveira et al. 2014).

Toxicological studies have indicated that mitochondria are potential targets for pro-oxidant action of selenides and diselenides, including ebselen and diphenyl diselenide. In general, the deleterious effects are demonstrated at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM. One of the first studies that simultaneously evaluated the effect of ebselen and diphenyl diselenide on mitochondria demonstrated that both compounds caused mitochondrial depolarization and swelling, effects that were associated with thiol oxidation, given that dithiotreitol prevented them (Puntel et al. 2010). In an extension of this study, using renal and hepatic mitochondria, ebselen and diphenyl diselenide inhibited the activity of complex I and II, without changing the complex III and IV. These effects were reversed by GSH and then related to the oxidation of critical thiol groups from mitochondrial complexes I and II (Puntel et al. 2013).

In the rat liver mitochondria, a recent study investigated diphenyl diselenide derivatives containing o-methoxy and p-methyl groups substituted in the aryl (25–100 μM) and revealed that only the compound containing the p-methyl group affected the mitochondrial membrane potential and decreased the State III respiration from 25 μM (Stefanello et al. 2020). Mitochondria from rat hippocampal astrocytes exposed to ebselen at a concentration of 100 μM showed disturbances in the membrane potential and calcium levels along with RS overproduction (Santofimia-Castano et al. 2013).

As the mitochondria are highly sensitive to redox status, pro-oxidant agents can disrupt mitochondrial homeostasis and trigger cell death via apoptosis. As stated above, diphenyl diselenide and ebselen induced in vitro deleterious effects on mitochondria that could elicit apoptosis. However, some in vitro findings show that exposure of healthy cells to both compounds did not culminate with apoptosis. In fact, human leukocytes exposed to diphenyl diselenide and ebselen, ranging from 10 to 50 μM, presented changes in mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase, and increase in RS production, but did not undergo apoptosis (Caeran Bueno et al. 2013). Accordingly, exposure of rat hippocampal astrocytes to ebselen (10–100 μM) caused viability loss, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondrial stress, without changing the activity of caspase-3, an apoptosis activation marker (Santofimia-Castaño et al. 2016; Santofimia-Castano et al. 2013).

On the other hand, the activation of death signaling by many organoselenium compounds toward unhealthy cells and pathogens has driven studies on the synthesis and screening for anti-cancer, anti-viral, and anti-fungal applications (these will be further addressed in detail at the pharmacological section).

In vivo toxicity of organoselenium compounds

Although diphenyl diselenide and ebselen are recognized as compounds with low toxicity in vivo, at high doses, they can elicit toxic effects, which vary a lot according to the species, exposure time, and route of administration. As demonstrated in vitro, mechanistically, the in vivo toxicity of ebselen, diphenyl diselenide, and its derivatives has been associated with oxidative events, including thiol depletion, lipid peroxidation, and inhibition of sulfhydryl enzymes, such as δ-ALA-D, Na+, K+ ATPase, and LDH (Nogueira and Rocha 2011; Nogueira et al. 2004). To date, the toxicological implications from acute and chronic exposures to organoselenium compounds on mammalian models have not been extensively reported in the literature. Therefore, we will also include here some findings found in non-mammalian models. Table 1 summarizes the acute and chronic effects of some organoselenium compounds.

Table 1.

Effects of acute and chronic treatments with diphenyl diselenide, ebselen, and selenomethionine

| Acute exposure | Chronic exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Treatments | Effects | Treatments | Effects |

| Mice | Diphenyl diselenide | |||

| 210 µmol kg−1 (i.p)a | Mortality | |||

| 150 µmol.kg−1 (i.p) | ↑ PTZ-induced seizure | |||

| 10 mg kg−1(i.p) | Stereotypy | |||

| Ebselen | ||||

| 340 µmol kg−1 (i.p)a | Mortality | |||

| Selenomethionine | Selenomethionine | |||

|

∼ 8 mg kg−1(i.p)a 8 mg Se kg−1 (i.p) |

Mortality Hepatic lipid peroxidation |

0.2 and 2 mg g−1(p.o) 50 days |

↑Liver Lipoperoxidation Arsenic-induced |

|

| Rats | Diphenyl diselenide | Diphenyl diselenide | ||

|

1200 µmol kg−1 (i.p)a 10 mg kg−1(i.p) 50 to 500 mg kg−1(i.g) |

Mortality Anxiety Seizures, brain lipid peroxidation in pups |

1 mg kg−1 (i.p) 21 days |

↑Hg deposition In liver and brain |

|

| Ebselen | ||||

|

10 mg kg−1 (s.c) 21 days |

Hepatic lipoperoxidation In suckling |

|||

| Selenomethionine | ||||

|

1.2–1.8 mg kg−1 (p.o) 13 weeks |

↓Weight Liver and pancreas damage |

|||

| Ebselen | ||||

| 400 µmol kg−1 (i.p)a | Mortality | |||

| Selenomethionine | ||||

| ∼4 mg kg−1(i.p)a | Mortality | |||

| 1 mg kg−1 (i.p) | Pancreatic damage | |||

| Rabbits | Diphenyl diselenide | |||

| 500 mmol kg−1 (i.p) | Mortality, hepatoxicity, and brain oxidative stress | |||

| Flyb | Diphenyl diselenide | |||

|

0.5–2 µM (p.o) 10 days |

Developmental delay | |||

|

1–10 µM (p.o) 3 days |

↑Hg toxicity in adult | |||

| Fish | Diphenyl diselenide | |||

|

5 ppm (p.o) 60 days |

↓weight Oxidative damage Silver catfish and Cyprinius carpo |

|||

| Selenomethionine | ||||

|

10–30 μg g−1(p.o) 90 days |

Behavioral changes, cardiac dysfunctions In adult Zebrafish |

|||

|

30–60 μg g−1(p.o) 30 days |

Cognitive impairment, brain oxidative stress In adult Zebrafish |

|||

|

100 µg L−1 (p.o) 48 hpf |

Embryonic teratogenesis in Zebrafish |

|||

|

30–60 μg g−1 (p.o) 30 days |

Growth retard, mortality, hematological disturbances in juvenile Steelhead trout |

|||

| Lambs | Selenomethionine | |||

| 1–8 mg/kg (p.o) |

Tachypnea, myocardial necrosis, pulmonary edema |

|||

aLD50 the dose of a test substance that is lethal for 50% of the animals, hpf hours post-fertilization, PTZ pentylenetetrazol, Flyb Drosophila melanogaster

Acute exposure

In rodents, the toxicity of diphenyl diselenide and ebselen varies depending on the route of administration, age, and species (Table 1). After acute administration by the intraperitoneal (i.p) route, diphenyl diselenide was more toxic to mice than rats (Meotti et al. 2003). On the other hand, the i.p. administration of diphenyl diselenide-loaded nanocapsules (50–1000 µmol kg−1) did not cause overt toxicity or death in mice (Stefanello et al. 2015a). The LD50 values for ebselen were very similar when intraperitoneally injected in mice and rats (Meotti et al. 2003).

Diphenyl diselenide was also toxic to rabbits, when administered by the i.p route at a dose of 500 µmol kg−1 caused mortality, hepatoxicity, and disruption of brain redox status (Straliotto et al. 2010).

By subcutaneous (s.c) and intragastric (i.g) routes, diphenyl diselenide usually exhibited lower toxicity than that observed after i.p administration. Acute intragastric or subcutaneous administration of diphenyl diselenide did not cause overt toxicity or death in rats and mice (da Luz Fiuza et al. 2015; Meinerz et al. 2014; Meotti et al. 2003; Wilhelm et al. 2009b).

By the intravenous route, sheep treated with a single dose of diphenyl diselenide (6 µmol kg−1) did not have any overt sign of toxicity until the end of observational period, namely 37 days (Leal et al. 2018).

Especially toward central symptoms from acute treatments, the first investigations demonstrated that an i.p administration of diphenyl diselenide increased the pentilentetrazole-induced seizure in mice (Table 1), but not in rats (Brito et al. 2006). Regarding the age of animals, diphenyl diselenide administered by s.c or i.g route did not cause seizures in adult rats or mice; however, in 12-day-old rat pups, oral acute treatment induced seizure episodes (Table 1) (Prigol et al. 2007). Diphenyl diselenide acutely administered at the dose of 10 mg kg−1 induced stereotypy in mice and anxiety-like behavior in rats, manifestations that were related to the inhibition of the brain monoamino oxidase (MAO-B) activity and increased levels of pro-inflammatory marker tumor necrosis factor α (TNF), respectively (Figueira et al. 2015; Yamakawa et al. 2020).

In non-mammalian models, some findings showed that the acute treatment of zebrafish with diphenyl diselenide and diphenyl diselenide-loaded nanocapsules, at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2 µM, did not cause behavioral impairments and/or oxidative stress (Ferreira et al. 2019b; Ibrahim et al. 2014b).

Chronic exposure

The toxic effects elicited by diphenyl diselenide from chronic treatments also vary in relation to the organisms (Table 1). Most of chronic protocols have applied dietary diphenyl diselenide, which have revealed that the long-term intake is relatively safe for several species. Evidence has been found to suggest that dietary diphenyl diselenide, from 1 to 3 ppm, was relatively secure for rats, rabbits, and some fish species after months of exposure, without eliciting either systemic or central signals of toxicity (Baldissera et al. 2020a; Barbosa et al. 2008; de Bem et al. 2006; dos Santos et al. 2020). However, the intake of high concentrations for a long time may culminate with toxic effects in fish. In fact, Silver catfish and Cyprinius carpio fed with 5 ppm diphenyl diselenide, for 60 days, had reduction in the weight and body length, and also showed increased lipid peroxidation in the liver, brain, and muscle (Menezes et al. 2014, 2016).

Here, we highlight that diphenyl diselenide chronic treatment (Table 1) did not induce toxicity in rats, but enhanced the Hg accumulation in the liver and brain as well as potentiated motor deficits and body-weight loss caused by methylmercury (MeHg) (Dalla Corte et al. 2013).

In vivo chronic toxicity data with ebselen are scarcer than diphenyl diselenide, but there is evidence that chronic subcutaneous administration of the compound (10 mg/kg, for 21 days) to suckling rats culminated with lipid peroxidation and non-protein thiol depletion in the liver (Farina et al. 2004).

In invertebrates, literature brings some findings from D. melanogaster as an organism model to study toxicology and pharmacology of dietary diphenyl diselenide. Accordingly, the toxicity of dietary diphenyl diselenide was dependent on sex of D. melanogaster both in relation to total body thiol depletion and disruption in the mRNA expression of the antioxidant enzymes like catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione S transferase (Occai et al. 2018).

Leão and collaborators exposed flies to diphenyl diselenide during both developmental and adult phases. Dietary diphenyl diselenide, ranging from 0.5 to 2 µM, affected the normal developmental success of D. melanogaster and also enhanced the toxicity of MeHg on development. In adult flies, diphenyl diselenide (1 to 10 μM) did not induce toxic effects, but increased the toxicity of MeHg on climbing ability and survival of individuals (Leão et al. 2018).

Moreover, diphenyl diselenide and MeHg co-exposure increased the Hg levels in the flies, an effect that was related to the formation of a less excretable complex between the selenium from the organoselenium and Hg. Accordingly, the same group had already demonstrated that diphenyl diselenide and MeHg co-exposure had increased the Hg content in the brain and liver of rodents (Dalla Corte et al. 2016, 2013). In flies and rats, the reduced intermediate of diphenyl diselenide (phenylselenol or selenophenol) may have reacted with MeHg to form a PhSe–HgMe complex. This complex possibly facilitated the break of –C–Se– and –Hg–C– bonds, releasing the insoluble HgSe salt (Madabeni et al. 2020).

In vivo toxicity of diphenyl diselenide derivatives and other organoselenium compounds

Similar to diphenyl diselenide, the toxic profile of diselenide derivatives varies depending on the species and administration route, and, in general, the intragastric and subcutaneous administrations were reported to be safer than intraperitoneal. For mice, the intragastric LD50 for diselenide derivatives, p-chloro and p-methoxyl substituted diselenides, was found to be > 1 mmol kg−1. For m-trifluoromethyl and benzylamino derivatives, the LD50 was estimated to be > 0.62 and 350 mg kg−1, respectively (Ibrahim et al. 2019; Savegnago et al. 2009).

The intragastric administration of p-methoxyl-substituted diselenide-nanoencapsulated (25 mg kg−1, 7 days) did not cause any alteration in hematological and oxidative damage markers, and enhanced the selenium levels in the blood, kidney, and liver of mice (Sari et al. 2017).

By the subcutaneous route, p-chloro diselenide derivative (1000 µmol kg−1) did not induce overt sign of toxicity in mice and reduced the toxicity of HgCl2 on the liver and kidney, as indicated by the restoration of δ-ALA-D, Na+, K+ ATPase, and lipid peroxidation to normal levels (de Freitas et al. 2012).

In rats, 2,2′-dithienyl diselenide derivative, at doses of 50 and 100 mg kg−1, caused systemic toxicity after intragastric administration, such as weight body loss, hepatotoxicity, inhibition of δ-ALA-D activity, lipid peroxidation, and death (Chagas et al. 2013a).

Acute intraperitoneal administration of vinyl chalcogenide 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-(phenylseleno)oct-2-en-1-one, at doses of 125–500 µg kg−1, was toxic to rats, increasing plasma alanine aminotransferase and causing hematological and behavioral changes. The compound also increased lipid and protein oxidation in the brain (de Andrade et al. 2014; dos Santos et al. 2012). Likewise, rats exposed chronically to this vinyl chalcogenide (i.p., 30 days), in addition to cause behavioral alterations, increased brain lipid and protein oxidation, thiol depletion, liver, and renal damage (Medeiros et al. 2012; Mello et al. 2012).

3,3′-Diselenodipropionic acid (DSePA), a synthetic derivative of selenocystine, has been extensively investigated as an antioxidant and radioprotective agent. The acute oral toxicity of DSePA is low in mice (LD50 ∼200 mg kg−1) and rat (LD50 ∼ 25 mg kg−1) when compared with its parent compound selenocystine and other organoselenium commonly used as a nutritional supplement, including methylselenocysteine and selenomethionine (Kunwar et al. 2018, 2020; Yang and Jia 2014). The mechanisms involved in the toxicity of DSePA have not been studied in detail, but considering its structure and its LD50 for rodents (which is greater than selenocystine); we can predict that its toxicity will be mediated by oxidation of thiol groups of critical target proteins. Although the acute in vivo toxicity of DSePA in mice has been described to be low in relation to selenocystine, we have to bear in mind the extreme sensitivity of humans to the toxic effects of selenocystine (Weisberger and Suhrland 1956). This aspect is important in view of the structural similarity of DSePA with selenocystine.

Regarding the in vivo toxicity of naturally occurring organoselenium compounds, we included here some toxicological studies published in the last decade with selenomethionine, methylselenocysteine, and selenocysteine, in which the findings with selenomethionine were the most prevalent (Table 1). Selenomethionine can be metabolized to selenide and provided selenium to be incorporated into selenoproteins. However, depending on the species, selenomethionine levels exceeding 0.2 ppm can become toxic (Schrauzer 2003).

Human cases of acute and/or chronic selenomethionine poisoning are rare, but, recently, a fatal case of occupational acute intoxication with this powdered amino acid was reported. After trying to open a sealed bag-container, the l-selenomethionine powder blew out back onto 30 years-old man. Selenomethionine contaminated his skin and clothes, and was also inhaled. A few hours after the contamination (about 5 h), the man died, and just before dying, he had abnormal blood pH (7.01), oxygen saturation (75%), glucose (17 mg 100 mL−1), bicarbonate (12 mEq L−1), urea (14 mg dL−1), creatinine (1.51 mg 100 mL−1), 11 mg L−1 of selenium (normal levels below 0.16 mg.L−1), and urine selenium levels of 25 mg L−1 (normal levels below 0.2 mg L−1) (Spiller et al. 2020).

In an experimental animal model, lambs orally administered with a single dose of selenium as selenomethionine (ranging from ∼ 1 to 8 mg of Se kg−1) developed tachypnea, whose severity and time to recovery were dose-dependent. Histopathologic alterations were also observed in the animals exposed to the higher doses, including myocardial necrosis, pulmonary edema, and hemorrhage (Tiwary et al. 2006).

In rats, the i.p. LD50 of selenomethionine was estimated to be ∼ 4 mg Se kg−1, whereas for mice ∼ 8 mg Se kg−1 (Schrauzer 2003). Indeed, rats intravenously injected, at a bolus dose of 1.0 mg Se kg−1 as selenomethionine, accumulated selenium preferably in the pancreas and had a significant increase in the serum amylase levels, a key marker of pancreatic damage.

The chronic toxicity of selenomethionine is considered lower than inorganic selenium forms, and often is reported in animals fed with too high levels. Rats fed for 8 weeks with selenomethionine (16 ppm of Se) did not develop signs of toxicity, whereas the same amount of selenium as sodium selenite produced hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and splenomegaly (Schrauzer 2003).

Oral administration of 0.5 and 1.0 mg selenomethionine, for 13 weeks, did not also induce toxic effects in rats. However, higher concentrations (1.2 and 1.8 mg Se kg−1 body weight.day−1) caused weight loss, liver, and pancreas damage and decreased food consumption (Schrauzer 2003).

In a mouse model, the supplementation of sufficient and excess levels of selenomethionine (0.2 and 2 mg Se−1 kg−1, respectively), for 50 days, improved the basal immunological parameters impaired by arsenic intoxication, but the two doses increased the hepatic lipid peroxidation arsenic-induced (Rodríguez-Sosa et al. 2013).

In non-mammalian models, most of the literature about the toxicity of selenomethionine intake is in fish. In zebrafish, chronic exposure to elevated dietary selenomethionine (from 10 to 30 μg g−1) has been associated with impairments in behavioral performance, aerobic metabolic capacity, and energy homeostasis (McPhee and Janz 2014). These adverse effects were correlated with the negative impact of chronic dietary selenomethionine on cardiac function, because zebrafish exposed to similar concentrations had a marked decrease in the ventricular contractile rate, stroke volume, and cardiac output, as well as disruption in the mRNA expression of cardiac remodeling enzymes (Pettem et al. 2017).

Adult zebrafish exposed to selenomethionine ∼30 and 60 μg g−1 of diet developed learning impairment, which was associated with oxidative stress and altered brain mRNA expression of dopaminergic system components (Naderi et al. 2017).

Chronic exposure of adult zebrafish to selenomethionine (34.1 μg g−1; 90 days) also displayed changes in social learning via dysregulation of key genes of the serotonergic pathway (Attaran et al. 2020).

In zebrafish embryos, selenomethionine at 100 µg L−1 induced significant deformities (lordosis and craniofacial malformation), which were partially attributed to oxidative stress, since N-acetylcysteine reduced the teratogenic signals (Arnold et al. 2016).

A study performed with steelhead trout in the juvenile stage fed on ∼ 8, 15, 30, and 60 μg Se g−1 diet in the form of selenomethionine, for 4 weeks, revealed that Se accumulated in a dose-dependent manner in all tissues. Moreover, the diets with selenomethionine at 30 μg g−1 or higher arrested growth and increased mortality and hematological disturbances (Lee et al. 2019).

Pharmacology of organoselenium compounds

The coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the worldwide spread of new SARS-CoV-2, has dominated the work of researchers in an unprecedented global effort to lead to the rapid discovery of drugs with the clinical potential to fighting this new infectious disease for which no specific drugs or vaccines are available (Roser et al. 2020).

Since the nutritional essentiality of selenium as a trace element for human health has been demonstrated (Schwarz and Foltz 1957), the multifaceted aspects of this nutrient have attracted worldwide clinical and research interest (Allingstrup and Afshari 2015; Navarro-Alarcon and Cabrera-Vique 2008; Oldfield 1987; Rayman 2012). However, the selenium status should be analyzed considering its U-shaped effects, exhibiting advantages in selenium-deficient individuals but specific health risks in those with selenium excess (Duntas and Benvenga 2015; Misu et al. 2012; Rayman 2020; Rayman et al. 2012; Rayman and Stranges 2013; Rocourt and Cheng 2013; Zhou et al. 2013).

Particularly, in China, where COVID-19 emerged, the concentration of selenium in the soil, which generally reflects its presence in food and the selenium levels in human populations, varies from deficiency to excess (Dinh et al. 2018). Based on this premise and knowing the immunomodulatory property of selenium (Guillin et al. 2019; Steinbrenner et al. 2015), a very recent published study from Rayman group reported the better recovering of COVID-19 patients related to certain regions of China that had the most selenium in soil (Zhang et al. 2020c).

Selenium, as a cyclic selenyl amide ebselen, also emerges in the pandemic scenario as a potential repurposing approved pharmaceutical drug with anti-viral activity for the treatment of COVID-19 (Sies and Parnham 2020).

Considering what was mentioned before, in this chapter, the pharmacology of organoselenium compounds is discussed, emphasizing properties beyond their well-known antioxidant activity.

Anti-viral activity

As previously described in Sect. 2.1 of this review, the pro-oxidant action of selenium compounds, including thiol oxidation, RS generation, DNA damage, and mitochondrial dysfunctions, can drive events that culminate in biological downstream effects by affecting kinases, phosphatases, and caspases, proteins involved in the DNA repair and transcription factors that regulate growth, proliferative, and death pathways in cancer cells and different pathogens. Furthermore, organoselenium compounds, particularly ebselen and diselenides, can oxidize critical thiol-containing proteins from viruses, bacteria, and fungi.

Ebselen has been shown to target critical proteins from different viruses due to its reaction with thiols. Toward human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), ebselen was found to be a potent integrase inhibitor, disrupting the interaction of the enzyme with the key growth-factor (lens-epithelium-derived growth-factor, LEDGF/p75), through the formation of a selenium–sulfur bond with a cysteinyl residue from the factor LEDGF/p75 (Zhang et al. 2020a). Similarly, the ebselen action as a potent HIV-1 capsid assembly disruptor was associated with its covalent binding to cysteine 198 and 218 residues in the HIV-1 capsid protein (Thenin-Houssier et al. 2016).

Regarding the hepatitis C virus, ebselen was recognized as a potent inhibitor of the NS3, a non-structural protein with helicase function. At concentrations higher than 10 µM, ebselen caused an irreversible inhibition and formation of covalent adducts with all cysteines present in the viral helicase (Mukherjee et al. 2014).

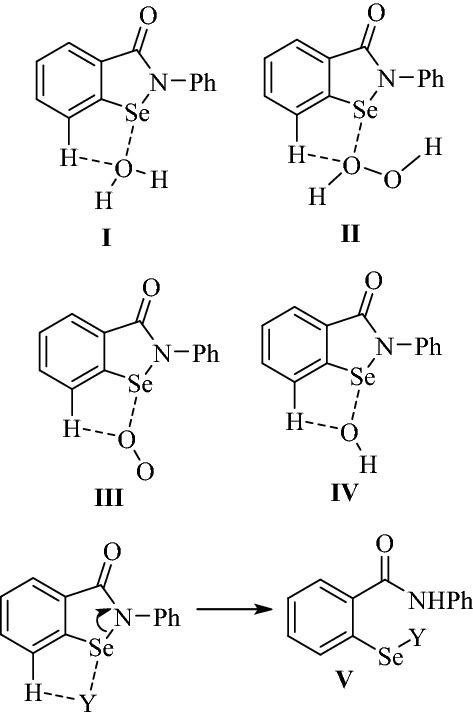

Currently, extensive computational–experimental screenings on SARS-CoV-2 have identified several promising drugs that could serve as effective inhibitors of the virus proteins, mainly toward the protease Mpro protease (NSP5), a non-structural sulfhydryl protein involved in the processing of Orf polyproteins 1a and 1ab. The products of hydrolysis of polyproteins 1a and 1ab (NSP4 to NSP 16) are involved in the replication of SARS-CoV-2 as well as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Pillaiyar et al. 2016).

Among various compounds investigated, ebselen appeared as one of the most potent inhibitors of the enzyme both in vitro and SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero cells. The IC50 for MPro protease was near 0.7 μM and for virus replication about 10 μM (Jin et al. 2020; Sies and Parnham 2020).

Ebselen covalently attaches to the catalytic cysteine residue from Mpro site active (Cys 145), forming selenosulfide that leads to the enzyme inactivation. Atomistic molecular simulations also provided evidence that ebselen exhibits high-affinity binding for sites localized between the II and III domains of the protein, an important allosteric effect that regulates the enzyme catalytic site (Menendez et al. 2020).

Ebselen and its derivatives have been demonstrated as inhibitors of both Mpro and the papain-like protease (PL-Pro) from SARS-CoV-2 (Ma et al. 2020); however, they had higher inhibitory effects against Mpro than PLpro (Zmudzinski et al. 2020).

The anti-viral properties of diphenyl diselenide and its derivatives have been only rarely explored. Therefore, diphenyl diselenide has been reported to have virucidal and anti-viral actions against in vitro herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV‐2), reducing the infectivity in 70.8% and 47%, respectively. Moreover, treatment with diphenyl diselenide was proven to be effective against oxidative stress and inflammation in HSV‐2-infected mice (Sartori et al. 2016, 2017).

In this way, a recent high-throughput screening of a series of new anti-viral diphenyl diselenide derivatives against human herpes virus type 1 (HHV-1) and encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) in A549-infected cells revealed their effectiveness against the two viruses. The majority of compounds tested, especially bis[2-(hydroxyphenylcarbamoyl)]phenyl diselenide, exhibited high activity against HHV-1 and moderate activity against EMCV. The anti-HHV-1 activity of most effective diselenides ranged between 2 and 40 μg mL−1 (Giurg et al. 2017). Recently, diphenyl diselenide was reported to be effective against bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 (BoHV-2), the agent of bovine herpetic mamillitis, both in vitro and in vivo in ewes transdermally infected with BoHV-2 (Amaral et al. 2020).

Antimicrobial activity

In the last decades, several studies regarding the antimicrobial activity of organoselenium compounds, such as ebselen, diphenyl diselenide, and selenide-based compounds, toward pathogenic fungi and bacteria have appeared in the literature (Di Leo et al. 2019).

Data from different laboratories have indicated that ebselen and various ebsulfur derivatives exhibited high efficacy against several kinds of clinically relevant fungal strains, among them Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, and Candida parapsilosis. From these studies, the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values found to ebselen ranged from ∼ 0.5 to 2 µg mL−1, whereas ∼ 0.02 to 12 µg mL−1 was reported to its derivatives (Di Leo et al. 2019; May et al. 2018; Ngo et al. 2016; Thangamani et al. 2017). Moreover, ebselen and its structural derivatives, such as benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one, and 2-methyl- and 2-n-propyl-benzisoselenazol derivatives, 2-phenylbenzisothiazol-3(2H)-one, and 2-phenyl-7-azabenzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one, exhibited similar inhibitory activity in assays with fluconazole-resistant strain of C. albicans (Orie et al. 2017).

Ebselen appeared as one of the most active compounds in studies that screened repurposing off-patented molecules with anti-fungal activity against Candida auris (De Oliveira et al. 2019; Wall et al. 2018).

The activity of ebselen nanoencapsulated was markedly increased against C. parapsilosis, C. albicans, and C. tropicalis when compared with the free form (Jaromin et al. 2018). In this way, Vartak and collaborators demonstrated the efficacy of a soluble vaginal film containing ebselen developed to treat vulvovaginal candidiasis, which exhibited an MIC value of 20 μM against Candida species, a concentration significantly lower when compared to classical anti-fungal as fluconazole (MIC 500 µM) and miconazole (MIC 100 µM) (Vartak et al. 2020b). The same group also showed the superior efficacy of a novel topical nanoemulgel of ebselen against C. albicans and C. tropicalis when compared to the effect of a clinically used drug terbinafine that was ineffective even at 100 µM (Vartak et al. 2020a).

Ebselen has also been suggested by several studies as a promising molecule to treat bacterial infections alone or in combination with other agents. The effectiveness of ebselen and its derivatives has already been demonstrated against diverse pathogens, including Staphylococcus ssp., Streptococcus ssp., and Enterococcus ssp. (Chen and Yang 2019; Thangamani et al. 2015a).

Ebselen exhibited a potent bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus multidrug-resistant clinical isolates and reduced the bacteria load in a mouse model of staphylococcal skin infections, acting also synergistically with traditional antimicrobials (Thangamani et al. 2015b).

After an evaluation against a broad array of enterococcal isolates in vitro, ebselen was uncovered as a promising agent for decolonization of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from the gastrointestinal tract (AbdelKhalek et al. 2018).

By targeting cysteine residues in the active site from critical enzymes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (antigen 85 complex; transpeptidase Ldt Mt2), ebselen and some derivatives were considered promising for treating tuberculosis (de Munnik et al. 2019; Favrot et al. 2013; Goins et al. 2017).

Similarly, from a high-throughput screening assay, ebselen was identified as a potent inhibitor of anthrax receptor (tumor marker endothelial 8, TEM8), via modification of a cysteine residue in the extracellular domain from the anthrax receptor (Cryan et al. 2013). In addition to the receptor modulation, Gustaffon and collaborators demonstrated that ebselen and its derivatives strongly inhibited Bacillus anthracis thioredoxin reductase (Gustafsson et al. 2016).

Screening ebselen and its derivatives for the treatment of ureolytic bacterial infections has revealed these organoselenium compounds as inhibitors of urease activity from Sporosarcina pasteurii and Helicobacter pylori through the interaction with a critical cysteine located at the entrance of the enzyme active site (Macegoniuk et al. 2016).

Very recent studies have demonstrated the synergistic therapeutic efficacy of ebselen and silver against the multidrug-resistant bacteria, including Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and S. aureus (Chen et al. 2019; Dong et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020).

Increasing evidence indicates the effectiveness of diphenyl diselenide, alone or as adjuvant with classical anti-fungal agents, against diverse strains of fungi. Diphenyl diselenide was effective against 32 Aspergillus isolates (MIC 64 µg mL−1), which increased the fungicidal action of the drug caspofungin, but was ineffective against an aspergillosis mouse model (Melo et al. 2020).

In vitro, diphenyl diselenide was tested against nineteen Pythium insidiosum isolates and showed an MIC ranging from ∼ 0.5 to 2.0 µg mL−1, the fungistatic activity was reproduced in an animal model of pythiosis (Loreto et al. 2012). Moreover, diphenyl diselenide also increased the efficacy of flucytosine against 30 clinical isolates of Cryptococcus spp. (Rossato et al. 2019).

On clinical C. glabrata strains, the diphenyl diselenide MIC ranged from 0.25 to > 64 (5.16 µg mL−1), values similar to that of found for fluconazole. Besides, a synergistic interaction was observed between diphenyl diselenide and the drug amphotericin B (Denardi et al. 2013).

Similar action profile was found against 40 clinical isolates of Sporothrix brasiliensis, in which diphenyl diselenide presented an MIC ranging from 4 to 32 µg mL−1 and a synergistic interaction with itraconazole (73%) (Poester et al. 2019).

Along with diphenyl diselenide, various other diselenide derivatives have been pointed out as effective inhibitors of growth and biofilm formation in fungi and bacteria. Herein we highlighted the compounds camphor diselenide, 2,2′-dithienyl diselenide, bis[ethyl-N-(2′-selenobenzoyl) glycinate], bis[2′-seleno-N-(1-methyl-2-phenylethyl) benzamide], bis[2-(hydroxyphenylcarbamoyl)]phenyl diselenide, and (Z, Z)-3,30-(4-(diseleno)phenylcarbamoyl)acrylic acid, that in addition to C. albicans also showed antibiofilm activity against several bacteria strains, including Enterococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus ssp., and Pseudomonas ssp. (Bueno Rosseti et al. 2014; Giurg et al. 2017; Pesarico et al. 2013; Rosseti et al. 2015; Sancineto et al. 2016; Shaaban et al. 2015).

There are also some studies comparing the anti-fungal potential of ebselen and diphenyl diselenide, alone or in combination with anti-fungal agents. One of them evaluated the effect of both compounds in combination with amphotericin B, caspofungin, itraconazole, and voriconazole against 25 clinical isolates of Fusarium spp. The MICs found for diphenyl diselenide and ebselen were 4–32 µg mL−1 and 2–8 µg mL−1, respectively. The most effective synergic combinations were found to ebselen + amphotericin B (88%), ebselen + voriconazole (80%), diphenyl diselenide + amphotericin B (72%), and diphenyl diselenide + voriconazole (64%) (Venturini et al. 2016).

Likewise, a comparative study toward C. parapsilosis showed that ebselen presented higher anti-fungal activity than diphenyl diselenide against both echinocandin-susceptible and -resistant strains (Chassot et al. 2016). The efficacy of both compounds was also addressed against Trichosporonasahii strains, in which ebselen exhibited an MIC ranging from ∼ 0.25 to 8 µg mL−1 and diphenyl diselenide from ∼8 to 64 µg mL−1 (Felli Kubiça et al. 2019).

It is worth mentioning that the mechanisms of antimicrobial action proposed for these organoselenium compounds generally involve similar effects for both fungi and bacteria. Overall, the studies about the antimicrobial activity of different organoselenium compounds have revealed their effectiveness in increasing cell membrane permeability, inhibiting sulfhydryl enzymes, and inducing redox dyshomeostasis in the cells mainly through GSH depletion and RS overproduction, events that can culminate in death (Di Leo et al. 2019).

Chemopreventive activity

A Janus-faced character of the element selenium, initially classified as carcinogenic (Nelson et al. 1943) and, subsequently, as anticarcinogenic (Shamberger and Frost 1969), has a long history. In that, some of the recent chapters based on clinical trials, cohort, and epidemiological studies have shown an inverse association between selenium intake and risk of cancers in humans. Because an extensive discussion of the literature on this field is outside of the scope of this review, the readers are directed to some comprehensive reviews on this topic (Hatfield et al. 2014; Jablonska and Vinceti 2015; Rayman 2020; Stolwijk et al. 2020).

Since the pioneering studies on the anti-cancer activity of organoselenium compounds (El-Bayoumy 1985; Fiala et al. 1991; Nayini et al. 1989; Reddy et al. 1985, 1987; Tanaka et al. 1985), basic research on this topic has moved ahead at a rapid pace, bringing perspectives in cancer prevention and promotion, cancer drug resistance, and molecular mechanisms behind these effects (Chen et al. 2020; Gopalakrishna et al. 2018; Spengler et al. 2019). However, no attempt is made here to thoroughly discuss the beginning studies on chemopreventive effects of organoselenium, as these have been reviewed elsewhere (Nogueira and Rocha 2011; Nogueira et al. 2004).

With regard to ebselen, this organoselenium compound has been proposed to induce RS formation, calcium dyshomeostasis, Bax activation, and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in different tumor cells, including multiple myeloma, pancreatic tumor, prostate, and leukocytes cancer lines (Gandin et al. 2018; Hanavan et al. 2015; Kaczor-Keller et al. 2020; Santofimia-Castaño et al. 2018). Besides, a very recent study reported that ebselen is an inhibitor of the 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase in leukemia cells, an enzyme essential for cell proliferation and tumor growth (Feng et al. 2020). Ebselen was proven to be a potent inhibitor of cell growth for the triple-negative model of breast cancer (Jupp and Giles 2012).

Ebselen and its derivatives have been also indicated as inhibitors of histone deacetylases in tumor cells (Wang et al. 2017b) and effective in reducing cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting multiple kinases with established roles in cancer progression (Bijian et al. 2012).

Thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1)-based drugs have been proposed as promising anti-cancer therapies, because the overexpression of this selenoprotein has been detected in many human tumors. Herein, we highlight the compound ethaselen, an ebselen derivative, which has been pointed out in both in vitro and in vivo studies as a potent anti-proliferative drug, by inhibiting TrxR1 in various types of tumors (Wang et al. 2011a, 2012; Wu et al. 2020). This promising action motivated the use of ethaselen in phase I clinical trial in China, which includes patients diagnosed with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. The phase 1a/1b finished in 2008, and currently, the compound will pass to phase 1c, where the patients will receive oral ethaselen tablets as treatment (600 mg/bid day) (Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02166242). Moreover, a number of methodological strategies have been carried out for synthesizing ethaselen derivatives with antitumoral activity (Ye et al. 2016).

In addition to TrR1, selenoprotein 15 (sep15) and GPx2 have been highlighted as important cellular redox regulators potentially involved in preventing and promoting cancer; however, the role of selenoproteins in cancer will be not addressed herein, but interested readers may refer to a comprehensive review published by Hatfield and collaborators (Hatfield et al. 2014).

In the search for novel organoselenium compounds with chemopreventive activity, a class of zidovudine (AZT)-based selenides, named chalcogenozidovudines, was screened as antitumoral candidates against human bladder carcinoma. This study uncovered 5′-(phenylseleno)zidovudine and its p-methyl and p-chloro derivatives as antitumor agents with potent apoptosis induction effects (de Souza et al. 2015). After a toxicological screening, the p-methyl derivative emerged as the most promising candidate for further antitumor studies by exhibiting lower toxicity than AZT on health immune cells and acute in vivo treatment (Ecker et al. 2017).

Increasing evidence indicates the chemopreventive activity of diselenides, especially diphenyl diselenide; as a result, one of the first related studies showed the effectiveness of diphenyl diselenide in inducing death in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y via ERK1/2-mediated apoptosis (Posser et al. 2011). The potential cytotoxic effects of diphenyl diselenide and diphenyl diselenide-loaded nanocapsules have also been reported against C6 glioma cells, in which both forms attenuated the tumor development. Similar results were observed against SK-Mel-103, a resistant melanoma cell line. In these studies, diphenyl diselenide at both forms caused a loss of viability, increased propidium iodide uptake, and nitrite levels in the malignant cells (Ferreira et al. 2019a, 2020).

A detailed discussion of the anti-proliferative activity of diselenide derivatives in malignant cells has been reviewed by others (Álvarez-Pérez et al. 2018; Gandin et al. 2018), and these reviews bring a list of compounds indicated as promising antitumor agents. Briefly, along with diphenyl diselenide on murine hepatoma cells (Hepa 1c1c7), the anti-proliferative potential of various diaryl, dialkyl, dipyridazinyl, dipyridinyl, and phenylcarbamate diselenides against other carcinoma cells have been addressed (Álvarez-Pérez et al. 2018; Gandin et al. 2018).

In terms of molecular mechanisms, cell-cycle arresting, caspase-independent and dependent apoptosis, p53 activation, and autophagy via c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation are among the cytotoxic effects reported for diorganyl diselenides, including symmetric aromatic diarylseleno and acylselenourea derivatives as well as m-trifluoromethyl-diphenyl diselenide, p-methoxyl-diphenyl diselenide, and diphenyl methylselenocyanate (Chakraborty et al. 2016; Díaz et al. 2018; Garnica et al. 2018).

Furthermore, one way by which the majority of agents, such as ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic agents, and some targeted therapies, kill cancer cells consists of directly or indirectly generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that block the key steps in the cell cycle (Watson 2013). Therefore, the use of antioxidant dietary supplements, and, consequently, the search for organoselenium compounds that could counteract the ROS generation and prevent tissue damage, allowing an increase in the maximum therapeutic dose of the anti-cancer drug, have been a matter of research interest (Panchuk et al. 2014, 2016).

In experimental models of cisplatin chemotherapy, ebselen has been proven to reduce ovarian damage and ototoxicity through modulation of oxidative injury and apoptosis (Orzáez et al. 2014; Soyman et al. 2018), whereas a naphthalimide-based organoselenium compound enhanced cisplatin antitumor efficacy and reduced its toxicity (Ghosh et al. 2015).

In an MCF-7-cultured cell model, diphenyl diselenide antigenotoxic activity has been associated with the prevention of cancer risk induced by tamoxifen hormone therapy (Melo et al. 2013). Besides, a synergistic antitumor action was identified when ebselen was associated with radiotherapy, which was attributed to the induction of apoptosis and inhibition of breast cancer cell progression (Thabet and Moustafa 2017).

Over the past decades, basic research in the anti-cancer potential of naturally occurring organoselenium compounds has made progress (Chen and Wong 2009; Ip and Ganther 1992; Jiang et al. 1999; Lu et al. 1995; Reddy et al. 2000; Sinha et al. 1999; Sinha and Medina 1997; Unni et al. 2005, 2001), and this knowledge has been translated with some success to clinical trials (Clark et al. 1996; Duffield-Lillico et al. 2003; Lippman et al. 2009; Mix et al. 2015a, b).

Aiming to use higher doses of chemotherapy and overcome drug resistance, the oral bioavailable methylselenocysteine has been investigated in combination with chemotherapeutic agents and proven to be effective against organ-specific toxicities induced by cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and oxaliplatin, and to enhance antitumor activity in animal models of cancer (Cao et al. 2004, 2014). Very recently, a phase I randomized double-blinded study compared methylselenocysteine and selenomethionine pharmacodynamic effects in cancer patients to determine a safe and effective dose to be used in combination with anti-cancer therapy. However, the dose of 400 μg was considered too low to achieve the levels of selenium in plasma (≥ 5 μM), which are expected to cause pharmacodynamic effects (Evans et al. 2020).

Previously published studies revealed that selenomethionine, the organic form of selenium used SELECT trial (Lippman et al. 2009), is ineffective against prostate cancer models (Li et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2009), whereas methylselenocysteine, classified in the second generation of organoselenium compounds, reduces tumor growth and castration-resistant progression of prostate tumor (Christensen et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015b; Zhan et al. 2013). Methylselenocysteine is considered the most effective among the other natural occurring selenium-containing molecules, because it is efficiently converted to the active intermediate methylselenol, requiring one-step activation by β-lyase, and does not get as easily serum protein interaction (Bhattacharya 2011; Ip 1998; Ip et al. 2000). Moreover, the anti-cancer effectiveness of methylselenocysteine and selenomethionine has been associated with the transamination reactions that generate α-keto acid selenium metabolites, which are potent inhibitors of histone deacetylases (Kassam et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2009; Pinto et al. 2014).

In addition to methylselenocysteine, methylseleninic acid has been reported as a direct precursor of methylselenol, the key metabolite responsible for selenium’s anti-cancer activity (El-Bayoumy and Sinha 2004), and effective against prostate cancer (Zhao et al. 2004). By inducing lipid peroxidation, methylseleninic acid sensitizes head–neck squamous cell carcinoma to radiation (Lafin et al. 2019).

Some of the molecular mechanisms underlying chemopreventive activity of naturally occurring organoselenium compounds described so far are the modulation of antioxidant defenses (selenoenzymes) and redox status of cells, programmed cell death, DNA repair, carcinogen detoxification, immune system, neo-angiogenesis, regulation of cell proliferation, and tumor cell invasion (Jung et al. 2013; Korbut et al. 2018; Pons et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2018a; Weekley et al. 2012; Whanger 2004; Zeng and Combs 2008; Zeng et al. 2011).

Antidepressant- and anxiolytic-like activities