Abstract

Genetic co-expression network (GCN) analysis augments the understanding of breast cancer (BC). We aimed to propose GCN-based modeling for BC relapse-free survival (RFS) prediction and to discover novel biomarkers. We used GCN and Cox proportional hazard regression to create various prediction models using mRNA microarray of 920 tumors and conduct external validation using independent data of 1056 tumors. GCNs of 34 identified candidate genes were plotted in various sizes. Compared to the reference model, the genetic predictors selected from bigger GCNs composed better prediction models. The prediction accuracy and AUC of 3 ~ 15-year RFS are 71.0–81.4% and 74.6–78% respectively (rfm, ACC 63.2–65.5%, AUC 61.9–74.9%). The hazard ratios of risk scores of developing relapse ranged from 1.89 ~ 3.32 (p < 10–8) over all models under the control of the node status. External validation showed the consistent finding. We found top 12 co-expressed genes are relative new or novel biomarkers that have not been explored in BC prognosis or other cancers until this decade. GCN-based modeling creates better prediction models and facilitates novel genes exploration on BC prognosis.

Subject terms: Cancer genetics, Breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a major health threat to women worldwide and supposedly results from stochastic molecular changes over long periods1. Resistance to therapy is not only common2,3 but expected as the progression of BC occurs4,5. Understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms2,6 and identifying novel genome profiles will aid in the development of therapies7,8. Microarray analyses of gene profiles offer potential prognostic information and identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for the prognosis of newly diagnosed BC9–14. However, since BC is a disease of complex coordinated molecular activities, it should be determined by the coordination of GCNs rather than DEGs. The information behind the GCN is of great importance15. GCN analyses are proven to be an efficient and systemic method to discuss biological network mechanisms or for the identification of novel biomarkers of BC10,11,16–22. In addition, when accompanied by the integration of publicly available genomic studies, they provide more accurate and robust results16,23. Therefore, we proposed GCN-based modeling to create better prediction models or gene panels of BC prognosis and explore novel biomarkers and putative functional pathways.

Results

Descriptive statistics of BC patients of validation data sets

There are 394 recurrence patients and 662 no recurrence patients and the average follow-up time are 8.86 ± 3.19 and 3.23 ± 2.85 years respectively. Except for ER status, younger age (OR 0.98 p < 0.007), bigger tumor size (OR 1.27 p < 0.001), positive lymph node (OR 1.27 p < 0.001) and higher grades (OR 2.7 ~ 2.9 p < 0.001) are statistically associated with BC relapse using univariable logistic regression (Table 1).

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of BC patients of validation data sets.

| RFS_event | OR | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 662) | Yes (n = 394) | |||||

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | |||

| Follow-up time (year) | 8.86 | 3.19 | 3.23 | 2.85 | 0.559 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 59 | 13 | 56 | 13 | 0.984 | 0.007 |

| Tumor size | 2.17 | 1.13 | 2.46 | 1.08 | 1.267 | 0.001 |

| n | % | |||||

| ER | ||||||

| Negative | 160 | 20.6% | 97 | 21.9% | 0.925 | 0.591 |

| Positive | 617 | 79.4% | 346 | 78.1% | ||

| Lymph node | ||||||

| Negative | 629 | 87.0% | 340 | 78.5% | 1.830 | |

| Positive | 94 | 13.0% | 93 | 21.5% | < 0.001 | |

| Grades | ||||||

| 1 | 133 | 26.0% | 36 | 11.1% | ||

| 2 | 221 | 43.2% | 173 | 53.2% | 2.892 | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 158 | 30.9% | 116 | 35.7% | 2.712 | < 0.001 |

RFS relapse-free survival, ER estrogen receptor, sd standard deviation. Odds ratio (OR) and p values are analyzed using univariable logistic regression.

GCN-based models outperform the reference model

In the validation data sets, there are only five clinical-pathological characteristics of ER status, lymph node, grade and tumor size available. There are many missing values in these variables. Lymph node status has adequate data and is an important factor to BC recurrence24–26. Therefore, only lymph node was included while modeling. Models were trained using stepwise cox hazard proportional regression. Model 1 served as a reference model for comparison, and its input predictors were 34 key candidate genes (KCGs). The input predictors of Model 2–4 were genes in GCNs with various criteria of r values of 0.82, 0.80 and 0.79. The final optimal models of Models 1–4 comprised 6, 13, 17, and 34 significant genes (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Model 5, created by the stepwise network modeling (SNM), contained eight genes. While the GCNs became larger, more important genes were included in the GCN-based models. The total R squared values increased from 0.05 to 0.21 in order from Models 1–4 and showed a significant goodness of fit (Likelihood ratio test p = 0 ~ 0.001) (Table 3). In addition, we carried out research on adopting other clinical variables and statistical method. In the entry model of multivariable logistic regression of five clinical-pathological factors (Supplementary Table 1), tumor size is the only significant factor related to BC recurrence that we included as a mandatory variable during modeling. The AUC and AUC are increasing from Model 1 to Model 4 in Supplementary Table 2 in line with above findings. In addition, we found that models included clinical variables had less prediction power than those without it.

Table 2.

The number of genes in the GCNs.

| r | Recurrence | No recurrence | Total number of unique genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| > 0.82 | 79 | 131 | 137 |

| > 0.80 | 110 | 216 | 221 |

| > 0.79 | 133 | 310 | 443 |

Table 3.

Characteristics of GCN-based models.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total # of genetic factors | 34 | 137 | 221 | 443 | 46 |

| # of genes in the model | 6 | 13 | 17 | 34 | 8 |

| ACC | 63.2–65.5 | 66.5–70.3 | 66.6–74.4 | 78.2–82.5 | 66.5–74.4 |

| AUC | 61.9–64.2 | 64.2–75 | 65.2–75.1 | 68.7–77.1 | 64.1–74.8 |

| R square | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| goodness of fit | < 0.001 | 1.21E−11 | 2.22E−16 | ~ 0 | 2.77E−12 |

ACC accuracy, AUC area under the curve.

aModel created using the approach of SNM.

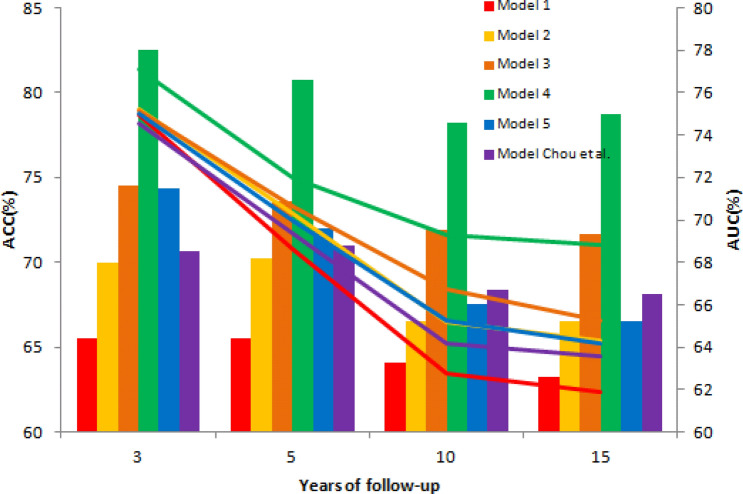

We evaluated the prediction performance of the models on 3, 5, 10 and 15 years of BC RFS using a logistic regression and ROC curve analysis. The results showed that Model 2–4 outperformed Model 1 (Accuracy; ACC 63.2–65.5%, Area under the Curve of ROC; AUC 61.9–64.2) measured by time-dependent accuracy (Supplementary Fig. 1) and time-dependent AUC (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, the top two precise models were Model 4 (ACC 78.2–82.5%; AUC 68.7–77.1%) and Model 3 (ACC 66.6–74.4%, AUC 65.2–75.1%) (Fig. 1). All the models reached the best prediction on the 3-year RFS.

Figure 1.

The ACCs (bar chart) and AUCs (histogram) of Model 1–5 and Model from Chou’s study28 for predicting the 3, 5, 10 and 15-year RFS in BC.

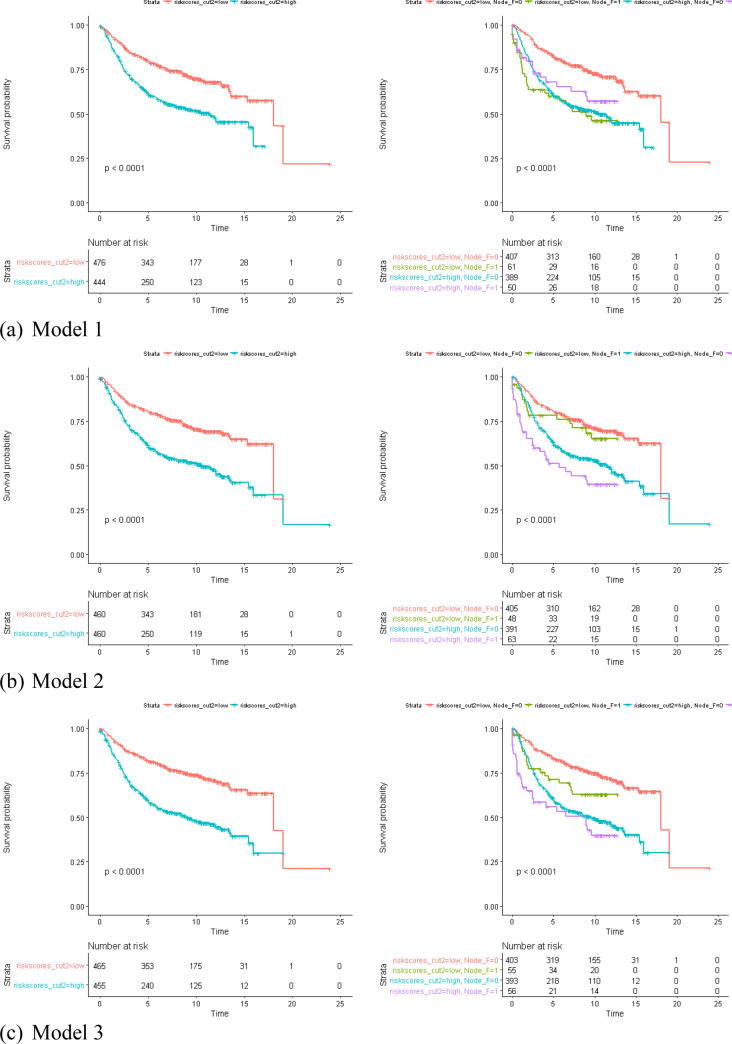

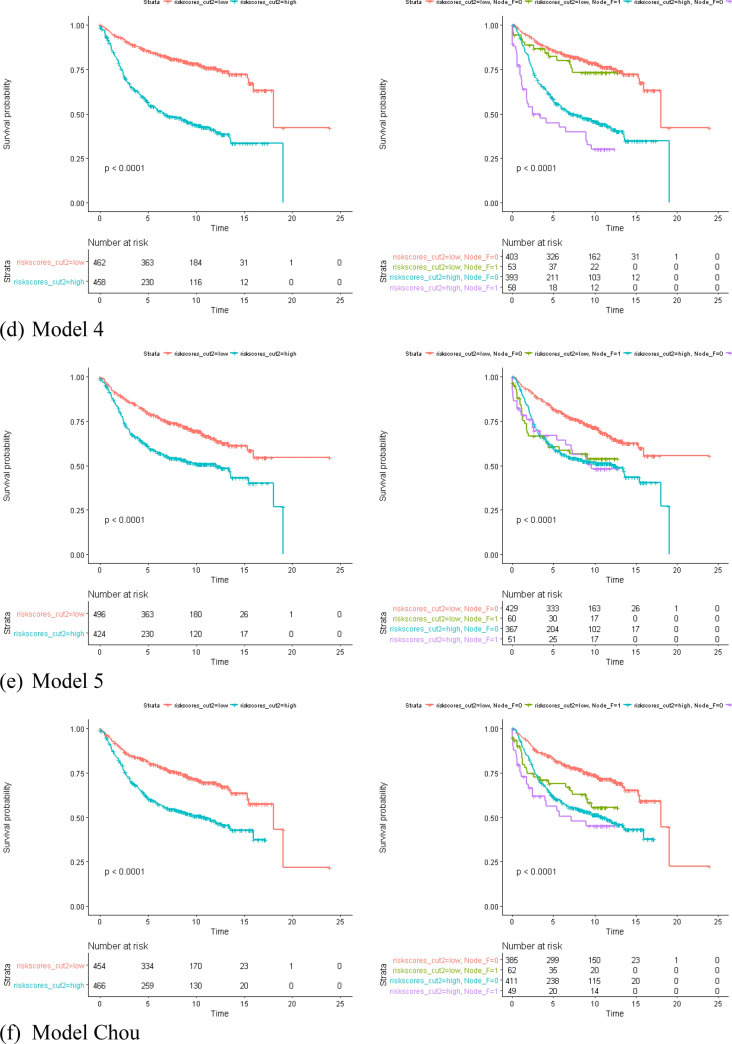

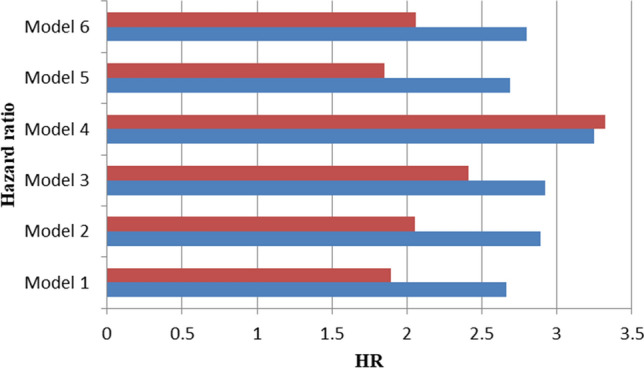

The risk scores of GCN-based models succeed in predicting RFS of BC

We used a partial Cox hazard proportional regression27 to compute the risk score of each model. The risk scores were used to predict the RFS of BC in the form of continuous and categorical variables (Fig. 2). All the risk scores significantly predicted the RFS of BC, and HRs ranged from 1.89 ~ 3.32 (p < 10–8) under the control of the node status. The risk score of Model 4 has the best discrimination for whether the high/low risk group developed recurrence (high risk group: HR 3.25, p ~ 0) under the control of the node status (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). According to the time-dependent the prediction error and AUCs in Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, model 4 was also the most precise prediction model followed by Model 3, Model 2, Model 5/Model 6, and Model 1, in that order. In summary, the GCN-based models outperformed the reference model, and the larger GCN-based model performed better.

Figure 2.

Partial cox regression plots of Models 1–5 and Model from Chou’s study28.

Figure 3.

Cox regression of the risk scores of each model on predicting the risk of relapse for breast cancer patients. Red bars are the hazard ratio (HR) of categorical risk scores of each model; blue bars are the hazard ratio (HR) of continuous risk scores of each model.

Validation of model prediction using independent data sets

We used the public independent mRNA microarray data of 1056 eligible primary BC tissues from KM plotter websites to do external validation. The outcomes are concordant with the modeling results. Model 4 has the best AUC 72.1–74.8% on predicting the RFS in 3, 5 and 10 years (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3). All models predict best on 3-year RFS.

Table 4.

The AUC of model validation using independent data sets.

| n-year RFS | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 69.2 [65.3;73.1] | 69.6 [65.6:73.6] | 70.6 [66.6;74.6] | 74.8 [71.1;78.6] | 69.7 [65.8;73.6] |

| 5 | 68 [64.5;71.6] | 68.7 [65.0;72.3] | 69.5 [65.9;73.1] | 74.6 [71.3;78.0] | 68.1 [64.5;71.6] |

| 10 | 66.8 [62.7;70.9] | 67.0 [62.9;71.1] | 67.4 [63.4;71.5] | 72.1 [68.2;75.9] | 66.5 [62.3;70.6] |

Models are under the control of node status.

GCN-based models outperform with less genetic predictors

We integrated the 46 significant genes from Model 1 to 4 and filtered out the most important genes using the criteria of uni-variable cox hazard proportional regression p < 0.001, HR > 1.5 or HR < 0.7 (= 1/1.5) under the control of the node status. Finally, we chose 12 genes and used stepwise forward cox hazard proportional regression to create Model 5, which was composed of eight genes, including AACS, C10orf5, CCNE2, EEF1E1, IDUA, LMNB1, MGC27165, and RORC. In comparison to the 21-gene model (Model 6) from Chou’s study28 using the same integrated GSE data sets, the GCN-based Model 5 (ACC 66.5–74.4%, AUC 64.1–74.8%) predicted as accurately as Model 6 (ACC 68.1–70.9%, AUC 63.4–74.5%) with only eight genetic predictors and had a better AUC (Fig. 1). This suggested that the GCN-based models not only reduced the dimension of the predictors but also filtered out the most representative and important genetic predictors.

Larger GCNs effectively provide more information on the novel genes related to recurrence

We also confirmed that larger GCNs effectively provided more information on the novel genes related to recurrence. In Models 2–4, we found some highly co-expressed with 34 candidate genes that statistically associated with recurrence, including Model 2—CCNA2, Model 3—CCNA2, IDUA, MGC27165, CCNE2, KIF14 and C10orf56 and Model 4—IDUA, MGC27165, CCNE2, KIF14, EBP and RORC (Supplementary Table 4).

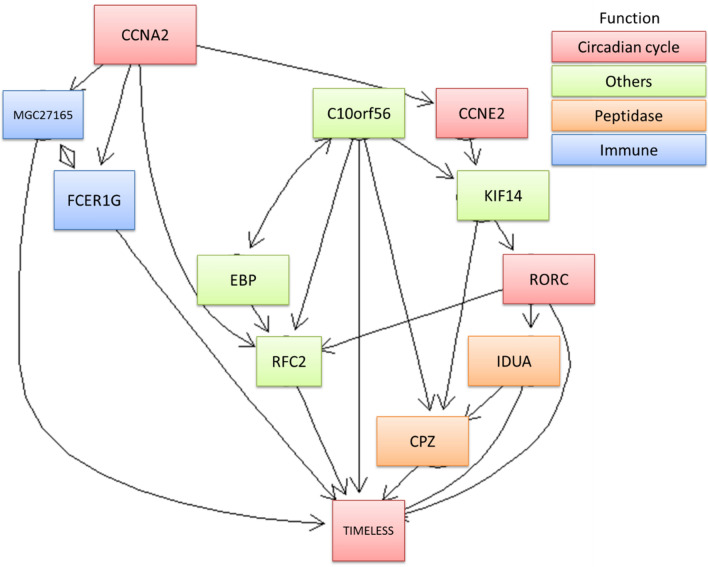

Predictive pathway of importance novel genes

The importance of the genes related to RFS was assessed by computing the proportion of the chi-square of each gene in each model. We plotted the relative importance of the genes in the order of the sum and average of importance indices (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Top 12 important genes are selected to plot the predictive pathways (Fig. 4). The function of these genes are clustered into 4 groups "Circadian Cycle (CCNA2, CCNE2, RORC, TIMELESS)", "Peptidase (IDUA, CPZ)", "Immune (MGC27165, FCER1G)" and others (C10orf56, KIF14, EBP, RFC2). The dysregulation of CCNA2 triggers the consequent reaction of other genes and leads to TIMELESS that influence the recurrence of BC.

Figure 4.

The predictive pathways of top 12 important co-expressed genes.

Discussion

Gene expression profiling of BC has shifted from differentially expressed genes (DEGs) to GCN analyses. GCN analyzes have been shown to aid comprehensive understanding of genomes regulation10,16,17. In this study, we proposed GCN-based modeling and SNM to create better prediction models of RFS in BC and explored novel significant co-expression genes. This is the first study to evaluate the prediction of GCN-based models created by various sizes of GCNs. We found that GCN-based modeling from larger GCNs created good prediction gene panels for BC recurrence either in the training and validation datasets (Table 4 and Fig. 3). Genetic predictors selected merely from the DEGs (DEG-based model) may miss key genetic information. GCN-based models can make up for the weakness and increase the prediction accuracy.

Though SNM model (Model 5) did not reach the best prediction outcome yet it predicted as accurately as Model 6 (from Chou’s study28), which created by our previous study contain 21 genes with less genetic predictors (eight genes). It indicated that GCN-based and SNM modelings are better approaches than DEG-based model (Model 1) for creating good gene panels with fewer genes but higher prediction accuracy.

Analysis of integrated microarray data sets facilitates the gene expression profiling of BC, but the lack of complete clinical characteristics is a big issue. Besides, most of the GCN studies16,18,29–31 are analyzed on already known biological pathways, the gene–gene interaction from text mining science articles or re-calculation using public genome data. However, those studies sometimes miss the information of unknown GCNs or biomarkers whose function has not yet been identified.

Our GCN-based modeling can make up for these deficiencies. 34 KCGs were selected by choosing the overlapping genes in five BC prognosis-related studies28,32–36. It is suggested that these genes play essential and stable roles in the mechanism of recurrence of BCs. The GCNs of 34 KCGs were assumed to include more significant novel genes related to recurrence even without considering the clinical characteristics. Therefore, even though we only considered one clinical variable node status, the results are still informative.

In general, the values of the time-dependent AUCs, time-dependent ACCs and HRs increased in the order of Model 4, Model3, Model 2, and Model 1. Model 4 predicted the RFS most accurately at any time point of 3, 5, 10 and 15 years. All the models applied in the short-term 3-year RFS performed with the best prediction (Fig. 1). GCN-based models effectively provide more novel and significant genetic information related to BC recurrence while the GCNs grow larger. The top 12 important genes from all the models were identified to plot the predictive pathway (Fig. 4) which started from CCNA2 and finished on TIMELESS. Functional annotations of 12 important genes are: (1) circadian cycle (CCNA2, CCNE2, RORC, TIMELESS); (2) immune (MGC27165, FCER1G); (3) peptidase [IDUA, CPZ]; (4) kinesin (KIF14); (5) DNA repair (RFC2); (6) membrane binding protein (EBP); and (7) nucleic acid binding and poly(A) RNA binding (C10orf56)37. Through literature review, these genes are biologically related to BC or other cancers11,38–56 in line with our bioinformatics findings.

It is notable that the role of TIMELSS in the progression of BC has not been well-characterized until these few years57–60. The overexpression of TIMELSS upregulated the expression and the trans-activity of the well-known oncogene MYC. Inhibition of MYC significantly blocked the effects of TIM on cancer stem cell population, cell invasion and anchor-independent cell growth60. Therefore, the functional gene–gene interactions in the pathway warrant further study to understand more about the mechanism of BC progression.

CCNA2 is a regulator of the cell cycle61. Its overexpression increased BC proliferation62 and is an early/transient/proliferation response biomarker63 for the prognosis of ER + BC and the monitoring of tamoxifen efficacy38.

CCNE2 has the same function as CCNA2. It might play an important role in acquired trastuzumab resistance in HER2 + breast cancer 40.

RORC (RAR Related Orphan Receptor C) is a suppressor gene46,64,65 associated with BC carcinogenesis. An RORC agonist suppresses breast cancer cell viability, migration, the EMT transition (microsphere outgrowth) and mammosphere-growth64.

IDUA(Iduronidase, Alpha-L) is associated with visceral organ metastatic disease in breast cancer49.

CPZ(Carboxypeptidase Z) expression was significantly lower ovarian cancers and may be relevant to the biology of high-grade serous ovarian cancers66. But no study discussed its role in BC.

MGC27165(IGHA1) was associated with BC survival time47 and was suppressed in triple negative breast cancer patients with poor prognosis11.

FCER1G (High-Affinity Immunoglobulin Epsilon Receptor Subunit Gamma)

Receptors for immunoglobulins [Fc-receptors (FcRs)] are widely expressed throughout the immune system67 and are related to antibody-based therapeutics, such as trastuzumab68.

C10orf56 (Chromosome 10 open reading frame 56, ZCCHC24) participated in tumorigenesis by inhibiting BET family proteins69. Its specific methylation pattern affected the expression level and was related to BC subtypes detection56.

KIF14 (Kinesin Family Member 14) is a prognostic predictor of BC 53,54,70. It promotes AKT phosphorylation and contributes to chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancers51,52.

RFC2 (Replication Factor C Subunit 2) is only mentioned in one study for its indirect association with BC and involvement in DNA repair 55.

EBP (emopamil-binding protein) is a human sterol isomerase (hSI) that is associated with a poorer BC disease-free survival71. SR31747A (sigma receptor ligand) binds with EBP and other proteins to exhibit antitumoral activity72. Few studies discuss its role in BC.

There are many missing data of clinical variables in validation data sets obtained from public database. Only significant lymph node status which had sufficient samples was included while modeling. It’s the limitation of the study. However, it will not alter the main findings that bigger genetic co-expression networks are more likely to produce good prediction models. In addition, all the significant identified biomarkers were reported to be associated with BC or other cancers. However, it will be more comprehensive to include as many clinical factors as possible for analysis.

Conclusion

We proposed GCN-based modeling and SNM method to construct more precise models than DEGs-based models with fewer genetic predictors. The results showed that all the GCN-based models outperformed the DEG-based model. Our framework systematically facilitates the discovery of novel co-expressed genes for BC prognosis without prior biological information of genes. We succeeded in finding relatively new co-expressed genes, such as TIMELESS, IDUA, CPZ, MGC27165, C10orf56 and so on that were found to be associated with BC or other cancers until this decade. In general, our GCN-based models and SNM facilitate studies to create prediction models and discover novel biomarkers.

Methods and materials

Microarray data sets

The mRNA microarray data of BC retrieved from Chou’ study28, including GSE 2034 (n = 286)32, GSE 2990 (n = 189)34, GSE 4922 (n = 249)35, and GSE 7390 (n = 198)33 of the NCBI GEO, and comprised a total of 922 cases and 13,452 genes, with 354 cases showing recurrence of breast cancer (38%) at the end of follow-up. A total of 111 node-positive cases (12%) and a total of 796 negative cases (86%) were included. The four data sets showed no difference in determining the distribution of recurrence (Supplementary Table 6). The pre-processing of the microarray data was denoted in Chou’s study28. They used quantile normalization73,74 to normalize all the mRNA expression values and calculated the median probe expression in a gene to represent the mRNA expression level. GSE739033 was used as the reference standard, and the other three data sets were log transformed to fit the former distribution. The workflow of study is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Workflow of the study.

Validation data sets

mRNA validation data sets were derived from KM plotter website (https://kmplot.com/) comprising 1809 BC tumor samples and 13,747 genetic characteristics. 1056 samples were included after excluding missing data (recurrence n = 394, no recurrence n = 662).

Thirty-four candidate genes

We chose the significant gene signatures from five studies (Supplementary Table 7). A comparison of the top 100 significant genes (Supplementary Table 8) related to BC recurrence from our previous study28 revealed 34 identical genes. (Supplementary Table 8) These 34 candidate genes have a stable and dynamic influence on the occurrence of recurrence of BC, and thus, these candidates were used to establish various GCNs.

Plot GCNs

We used R version 3.2.2 software (http://www.r-project.org)75 for the statistical computing and graphics. The GCN was developed using the package visNetwork76. The correlation coefficient, hierarchical clustering, coefficient of variation, and Cox hazard proportional regression were computed using the cor, hclust, co.var, and coxph functions. Due to variations in genotype and recurrence, the data were divided into two data sets by recurrence status for analysis.

The 34 KCGs were essential nodes in the GCNs. A Spearman's rank correlation analysis was applied on the 34 KCGs and all the other genomes of 13,418 genes. The genes with an r value over the threshold we set were selected and drawn in the GCNs. If the edges, starting from each node (gene) in the GCNs, were over two, only the most associative two were kept in order to identify the most important GCNs.

The regulation of the genetic networks of recurrence versus no recurrence is different. The GCNs for recurrence and no recurrence cases were drawn separately. The regulation of the recurrence of BCs was what we cared most about. Therefore, we plotted 2–4 times the size of 34 KCG GCN of recurrence data with the correlation thresholds of 0.82, 0.80 and 0.79 (Table 2).

Create GCN-based cox hazard proportional regression models and SNM

We obtained four groups of genetic predictors of four GCNs under r thresholds of 0.82, 0.80 and 0.79 to create prediction models of RFS in BCs (Table 2). Stepwise forward cox hazard proportional regression was used to select significant genes which variance inflation factor (VIF) < 10, a chosen significance level for entry (SLE) = 0.08 and the chosen significance level for stay (SLS) = 0.05. We gathered all significant genes from Models 1–4 and filtered out the most important genes based on the criteria of the uni-variable cox hazard proportional regression p < 0.001, HR > 1.5 or HR < 0.7 (1/1.5) under the control of the node status. Using these important genes, We these important genes and stepwise forward cox hazard proportional regression to create model 5. We named the procedure used to create Model 5 as stepwise network modeling (SNM).

Partial cox hazard proportional regression

To compare the prediction of the various models, we used a partial cox hazard proportional regression for constructing the mutually uncorrelated components of the genetic predictors in each model using the function of PCRf developed by Li and Gui27. This method was useful in building a parsimonious predictive model that accurately predicted the survival based on the mRNA expression profile. Predictive components whose p values were less than 0.05 (uni-variable Cox hazard proportional regression) were selected to rebuild a model [as shown in formula (1)]. The risk scores were computed by summing up the multiplication of the coefficient and selecting the component scale in the Cox hazard proportional regression [as shown in formula (2)]. Since the mean of each component scale was zero, we set zero as the cut-off point to categorize the patients into the high/low risk score groups. The Cox hazard proportional regression of the components is written as shown in formula (1). xi is the component extracted by the partial Cox hazard proportional regression. The risk scores were computed by formula (2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

Time-dependent AUC and prediction error

The area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve is a well-established indicator for assessing how well a prediction model performs. AUC ranges from 0 to 1. A model whose predictions are 100% wrong has an AUC of 0; one whose predictions are 100% correct has an AUC of 177. The classical approach of the AUC analysis considers the event (disease) status and marker value to be fixed over time. However, in practice, both the disease status and marker value change over time. Thus, a time-dependent AUC is more appropriate78. We evaluated the prediction performance of each model by computing the time-dependent AUC and prediction error using the R package of "survAUC"79.

Predictive pathway graph

Understanding cause-effect relationships between variables is of primary interest in cancer science. Usually, experimental intervention is used to confirm these relationships, but this can be infeasible because of time and cost. However, Kalisch et al.80 introduced "pcalg" to effectively explore causal relationships of important biomarkers in BC recurrence. Therefore, we used the mRNA dataset and R packages of "pcalg" and "Rgraphviz" to plot the predictive pathway. The alpha was set at 0.01.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data used in the article are public available data from NCBI GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and KM plotter (https://kmplot.com/analysis/). According to item two of the regulation "得免取得研究對象同意之人體研究案件範圍(Scope of human research cases exempt from obtaining consent) " (https://www.mohw.gov.tw/dl-45112-b708e126-a9c4-4842-ac83-ba6561948a2f.html), it denotes that " Use legally publicly known information and use the information for its publicly known purpose " meets the scope of the exemption.

Consent for publication

None.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- GCN

Genetic co-expression network

- SNW

Stepwise network modeling

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DAG

Directed acyclic graph

- KCG

Key candidate genes

Author contributions

Yu-Tien Chang conceived of the study, analyzed and wrote the manuscript drafts. Huan-Ming Hsu supervised and interpreted data. Chen Chien-Ting and Jian Chen-En analyzed the data. Yu-Jia Chang reviewed and revised the manuscript drafts. Chi-Wen Chang, Yuan-Kuei Li, Yu-Jia Chang, Jyh-Cherng Yu, Chien-Ting Chen, Chen-En Jian, Meng-Chiung Lin, Kang-Hua Chen, Ming-Hao Kuo, Chia-Shiang Cheng, Ya-Ting Chang, Yi-Syuan Wu, Hao-Yi Wu, Ya-Ting Yang and Je-Ming Hu commented on the manuscript drafts. Chien-An Sun , Hung-Che Lin and Chen Lin gave revision suggestions. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The studies were supported by grants from Songshan Branch of Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center (Grant 201704) and Taoyuan Armed Forces General Hospital (Grant TYAFGH-D-110031) .

Data availability

The data sets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and can be downloaded in GEO Data sets (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the author list as a previous version of the author list was erroneously published. The order of author names was incorrect. Chien-An Sun, Chen Lin, and Hung-Che Lin were omitted from the author list. In addition, Yu-Jia Chang was omitted as an equally contributing author.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yuan-Kuei Li, Huan-Ming Hsu, Meng-Chiung Lin, Chi-Wen Chang, Chi-Ming Chu and Yu-Jia Chang.

Change history

5/4/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-89147-x

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-84995-z.

References

- 1.Anderson WF, Matsuno R. Breast cancer heterogeneity: A mixture of at least two main types? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006;98:948–951. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dastmalchi N, et al. Molecular mechanisms of breast cancer chemoresistance by immune checkpoints. Life Sci. 2020;263:118604. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jabbarzadeh Kaboli P, et al. Akt-targeted therapy as a promising strategy to overcome drug resistance in breast cancer—A comprehensive review from chemotherapy to immunotherapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2020;156:104806. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Morales-Vasquez F, Hortobagyi GN. Overview of resistance to systemic therapy in patients with breast cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007;608:1–22. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-74039-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keikha M, Barreto GE, Gonzalez J, Sahebkar A. Bioinformatic study of involved mechanisms in relapse and drug resistance of tamoxifen-treated breast cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.2174/1871520620666201029114253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj U, Aier I, Semwal R, Varadwaj PK. Identification of novel dysregulated key genes in breast cancer through high throughput ChIP-Seq data analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3229. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03534-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raguz S, Yague E. Resistance to chemotherapy: New treatments and novel insights into an old problem. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99:387–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta G, et al. Unmet clinical need: Developing prognostic biomarkers and precision medicine to forecast early tumor relapse, detect chemo-resistance and improve overall survival in high-risk breast cancer. Ann. Breast Cancer Ther. 2020;4:48–57. doi: 10.36959/739/525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar R, Sharma A, Tiwari RK. Application of microarray in breast cancer: An overview. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012;4:21–26. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.92726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourdakou MM, Athanasiadis EI, Spyrou GM. Discovering gene re-ranking efficiency and conserved gene-gene relationships derived from gene co-expression network analysis on breast cancer data. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20518. doi: 10.1038/srep20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu HM, et al. Six novel immunoglobulin genes as biomarkers for better prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer by gene co-expression network analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4484. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40826-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang C, et al. Network-based approach to identify biomarkers predicting response and prognosis for HER2-negative breast cancer treatment with taxane-anthracycline neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7515. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Q, et al. Co-expression network analysis identified candidate biomarkers in association with progression and prognosis of breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019;145:2383–2396. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourgain C, Pourtau L, Mazouni C, Bungener M, Bonastre EJ. Imperfect biomarkers for adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage breast cancer with good prognosis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;246:112735. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, et al. Weighted frequent gene co-expression network mining to identify genes involved in genome stability. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L, et al. MetaDCN: Meta-analysis framework for differential co-expression network detection with an application in breast cancer. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:1121–1129. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin J, Chen YH. Molecular-level effects of eribulin and paclitaxel on breast cancer based on differential co-expression network analysis. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016 doi: 10.4238/gmr.15028192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, et al. The application of gene co-expression network reconstruction based on CNVs and gene expression microarray data in breast cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:1627–1637. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0902-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, J., Huang, K., Xiang, Y. & Jin, R. In International Joint Conference on Bioinformatics, Systems Biology and Intelligent Computing, 2009. IJCBS '09 428–434 (IEEE, 2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Li Z, et al. Profiling and integrated analysis of differentially expressed circRNAs as novel biomarkers for breast cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2020;235:7945–7959. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma L, et al. Construction and comprehensive analysis of a ceRNA network to reveal potential novel biomarkers for triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020;12:7061–7075. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S260150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan A, et al. An integrated systems biology and network-based approaches to identify novel biomarkers in breast cancer cell lines using gene expression data. Interdiscip. Sci. 2020;12:155–168. doi: 10.1007/s12539-020-00360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon, Y., Lee, J. & Park, S. In Sixth IEEE Symposium on BioInformatics and BioEngineering (BIBE'06). 94–102.

- 24.Braunstein LZ, et al. Breast-cancer subtype, age, and lymph node status as predictors of local recurrence following breast-conserving therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;161:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim SW, et al. Lymph node ratio as a risk factor for locoregional recurrence in breast cancer patients with 10 or more axillary nodes. J. Breast Cancer. 2016;19:169–175. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solak, M. et al. The lymph node ratio as an independent prognostic factor for non-metastatic node-positive breast cancer recurrence and mortality. J. BUON20, 737–745 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26214625. [PubMed]

- 27.Li H, Gui J. Partial Cox regression analysis for high-dimensional microarray gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(Suppl 1):i208–215. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou HL, et al. Gene expression profiling of breast cancer survivability by pooled cDNA microarray analysis using logistic regression, artificial neural networks and decision trees. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, Y., Xuan, J., de Los Reyes, B. G., Clarke, R. & Ressom, H. W. Network motif-based identification of breast cancer susceptibility genes. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc2008, 5696–5699. 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4650507 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Dutta B, et al. A network-based, integrative study to identify core biological pathways that drive breast cancer clinical subtypes. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;106:1107–1116. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu R, Guo CX, Zhou HH. Network-based approach to identify prognostic biomarkers for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treatment with tamoxifen. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015;16:317–324. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2014.1002360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desmedt C, et al. Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:3207–3214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sotiriou C, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: Understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivshina AV, et al. Genetic reclassification of histologic grade delineates new clinical subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10292–10301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu L, Tan AC, Winslow RL, Geman D. Merging microarray data from separate breast cancer studies provides a robust prognostic test. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.GeneCards Database. ZCCHC24 Gene—GeneCards|ZCH24 Protein|ZCH24 Antibody. http://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=ZCCHC24 (2017).

- 38.Gao T, et al. CCNA2 is a prognostic biomarker for ER+ breast cancer and tamoxifen resistance. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng W, et al. The dysregulated expression of KCNQ1OT1 and its interaction with downstream factors miR-145/CCNE2 in breast cancer cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018;49:432–446. doi: 10.1159/000492978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tormo E, et al. The role of miR-26a and miR-30b in HER2+ breast cancer trastuzumab resistance and regulation of the CCNE2 gene. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:41309. doi: 10.1038/srep41309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taghavi A, et al. Gene expression profiling of the 8q22-24 position in human breast cancer: TSPYL5, MTDH, ATAD2 and CCNE2 genes are implicated in oncogenesis, while WISP1 and EXT1 genes may predict a risk of metastasis. Oncol. Lett. 2016;12:3845–3855. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pegoraro S, et al. A novel HMGA1-CCNE2-YAP axis regulates breast cancer aggressiveness. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19087–19101. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, Meng Q, Yu Q, Zhou Z, Li L. Evaluation of c-myc and CCNE2 amplification in breast cancer with quantitative multi-gene fluorescence in-situ hybridization. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2014;43:455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai D, Zhang X, Chen HW. A master regulator of cholesterol biosynthesis constitutes a therapeutic liability of triple negative breast cancer. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2020;7:1701362. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2019.1701362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh TG, et al. The nuclear receptor, RORgamma, regulates pathways necessary for breast cancer metastasis. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oh TG, et al. PRMT2 and RORgamma expression are associated with breast cancer survival outcomes. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014;28:1166–1185. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Z, Li M, Hua Q, Li Y, Wang G. Identification of an eight-lncRNA prognostic model for breast cancer using WGCNA network analysis and a Coxproportional hazards model based on L1-penalized estimation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019;44:1333–1343. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeong J, et al. Higher densities of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells are associated with better prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;163:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savci-Heijink CD, Halfwerk H, Koster J, Horlings HM, van de Vijver MJ. A specific gene expression signature for visceral organ metastasis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:333. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5554-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mamoor, S. Carboxypeptidase Z is differentially expressed in high-grade serous ovarian cancers. 10.31219/osf.io/7me3r (2020).

- 51.Singel SM, et al. A targeted RNAi screen of the breast cancer genome identifies KIF14 and TLN1 as genes that modulate docetaxel chemosensitivity in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:2061–2070. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singel SM, et al. KIF14 promotes AKT phosphorylation and contributes to chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2014;16:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corson TW, Gallie BL. KIF14 mRNA expression is a predictor of grade and outcome in breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:1088–1094. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerashchenko TS, et al. The activity of KIF14, Mieap, and EZR in a new type of the invasive component, torpedo-like structures, predetermines the metastatic potential of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020 doi: 10.3390/cancers12071909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Badura M, Braunstein S, Zavadil J, Schneider RJ. DNA damage and eIF4G1 in breast cancer cells reprogram translation for survival and DNA repair mRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:18767–18772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203853109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen L, et al. Identifying methylation pattern and genes associated with breast cancer subtypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3390/ijms20174269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu A, et al. Genetic and epigenetic associations of circadian gene TIMELESS and breast cancer risk. Mol. Carcinog. 2012;51:923–929. doi: 10.1002/mc.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mao Y, et al. Potential cancer-related role of circadian gene TIMELESS suggested by expression profiling and in vitro analyses. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:498. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tozlu-Kara S, et al. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of estrogen receptor alpha-positive postmenopausal breast carcinomas: Identification of HRPAP20 and TIMELESS as outstanding candidate markers to predict the response to tamoxifen. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;39:305–318. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chi L, et al. TIMELESS contributes to the progression of breast cancer through activation of MYC. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19:53. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0838-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Kojetin D, Burris TP. Anti-proliferative actions of a synthetic REV-ERBalpha/beta agonist in breast cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015;96:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pei J, et al. NEK5 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation through up-regulation of Cyclin A2. Mol. Carcinog. 2019;58:933–943. doi: 10.1002/mc.22982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor KJ, et al. Dynamic changes in gene expression in vivo predict prognosis of tamoxifen-treated patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R39. doi: 10.1186/bcr2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oh TG, et al. The nuclear receptor, RORγ, regulates pathways necessary for breast cancer metastasis. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cadenas C, et al. Loss of circadian clock gene expression is associated with tumor progression in breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3282–3291. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.954454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mamoor S. Carboxypeptidase Z is differentially expressed in high-grade serous ovarian cancers. OSF Preprints. 2020 doi: 10.31219/osf.io/7me3r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fc-receptors as regulators of immunity. Adv. Immunol. 2007;96:179–204. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karagiannis P, et al. Characterisation of an engineered trastuzumab IgE antibody and effector cell mechanisms targeting HER2/neu-positive tumour cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII. 2009;58:915–930. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0607-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeng H, et al. Feedback activation of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor limits response to histone deacetylase inhibitors in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:459–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li TF, et al. Overexpression of kinesin superfamily members as prognostic biomarkers of breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:123. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simony-Lafontaine J, et al. Immunocytochemical assessment of sigma-1 receptor and human sterol isomerase in breast cancer and their relationship with a series of prognostic factors. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;82:1958–1966. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berthois Y, et al. SR31747A is a sigma receptor ligand exhibiting antitumoural activity both in vitro and in vivo. Br. J. Cancer. 2003;88:438–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y, Sun G, Ji Z, Xing C, Liang Y. Weighted change-point method for detecting differential gene expression in breast cancer microarray data. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017).

- 76.visNetwork: network visualization using 'vis.js' library v. R package version 1.0.3 (2016).

- 77.Developer, G. Classification: ROC Curve and AUC, https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/crash-course/classification/roc-and-auc (2012).

- 78.Kamarudin AN, Cox T, Kolamunnage-Dona R. Time-dependent ROC curve analysis in medical research: Current methods and applications. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017;17:53. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0332-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.survAUC: Estimators of prediction accuracy for time-to-event data (2012).

- 80.Kalisch M, Mächler M, Colombo D, Maathuis MH, Bühlmann P. Causal inference using graphical models with the R package pcalg. J. Stat. Softw. 2012;47:1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v047.i11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and can be downloaded in GEO Data sets (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/).