Abstract

The key to understanding the evolutionary origin and modification of phenotypic traits is revealing the responsible underlying developmental genetic mechanisms. An important organismal trait of ray-finned fishes is the gas bladder, an air-filled organ that, in most fishes, functions for buoyancy control, and is homologous to the lungs of lobe-finned fishes. The critical morphological difference between lungs and gas bladders, which otherwise share many characteristics, is the general direction of budding during development. Lungs bud ventrally and the gas bladder buds dorsally from the anterior foregut. We investigated the genetic underpinnings of this ventral-to-dorsal shift in budding direction by studying the expression patterns of known lung genes (Nkx2.1, Sox2, and Bmp4) during the development of lungs or gas bladder in three fishes: bichir, bowfin, and zebrafish. Nkx2.1 and Sox2 show reciprocal dorsoventral expression patterns during tetrapod lung development and are important regulators of lung budding; their expression during bichir lung development is conserved. Surprisingly, we find during gas bladder development, Nkx2.1 and Sox2 expression are inconsistent with the hypothesis that they regulate the direction of gas bladder budding. Bmp4 is expressed ventrally during lung development in bichir, akin to the pattern during mouse lung development. During gas bladder development, Bmp4 is not expressed. However, Bmp16, a paralogue of Bmp4, is expressed dorsally in the developing gas bladder of bowfin. Bmp16 is present in the known genomes of Actinopteri (ray-finned fishes excluding bichir) but absent from mammalian genomes. We hypothesize that Bmp16 was recruited to regulate gas bladder development in the Actinopteri in place of Bmp4.

Keywords: Bmp16, development, gas bladder, lungs, ray-finned fishes

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The origin of phenotypic novelties, such as jaws and limbs is central to understanding the history of life, and it is now possible to expose the genetic underpinnings of such novel traits using modern developmental genetics. An important evolutionary novelty characterizing most of the ~30,000 species of living ray-finned fishes (including teleosts; Nelson, Grande, & Wilson, 2016) is the air-filled gas bladder, which is used primarily for buoyancy control in most species which have one (Helfman, Collette, Facey, & Bowen, 2009; Steen, 1970). Though Darwin (1859) argued that lungs were derived from the gas bladder, Sagemehl (1885) subsequently argued that the gas bladder is the more derived structure. This has been the dominant view since (Graham, 1997; Liem, 1988; Romer & Parsons, 1970) and is consistent with the phylogenetic distribution of these traits across a well-supported phylogeny of bony vertebrates (Hughes et al., 2018; Near et al., 2012). The homology of lungs and gas bladders as air-filled organs is well supported. Both develop from the anterior foregut endoderm, are supplied by the pulmonary artery, produce surfactant proteins, and express a suite of regulatory genes with known lung-specific function (Cass, Servetnick, & McCune, 2013; Daniels et al., 2004; Goodrich, 1958; Longo, Riccio, & McCune, 2013). The defining difference between gas bladders and lungs is the direction of budding from the anterior foregut. Gas bladders lie just ventral to the spine (Figure 1a) and bud from the dorsal (or dorsolateral) wall, while lungs bud from the ventral (or ventrolateral) wall (Cass et al., 2013; Graham, 1997; Wilder, 1877).

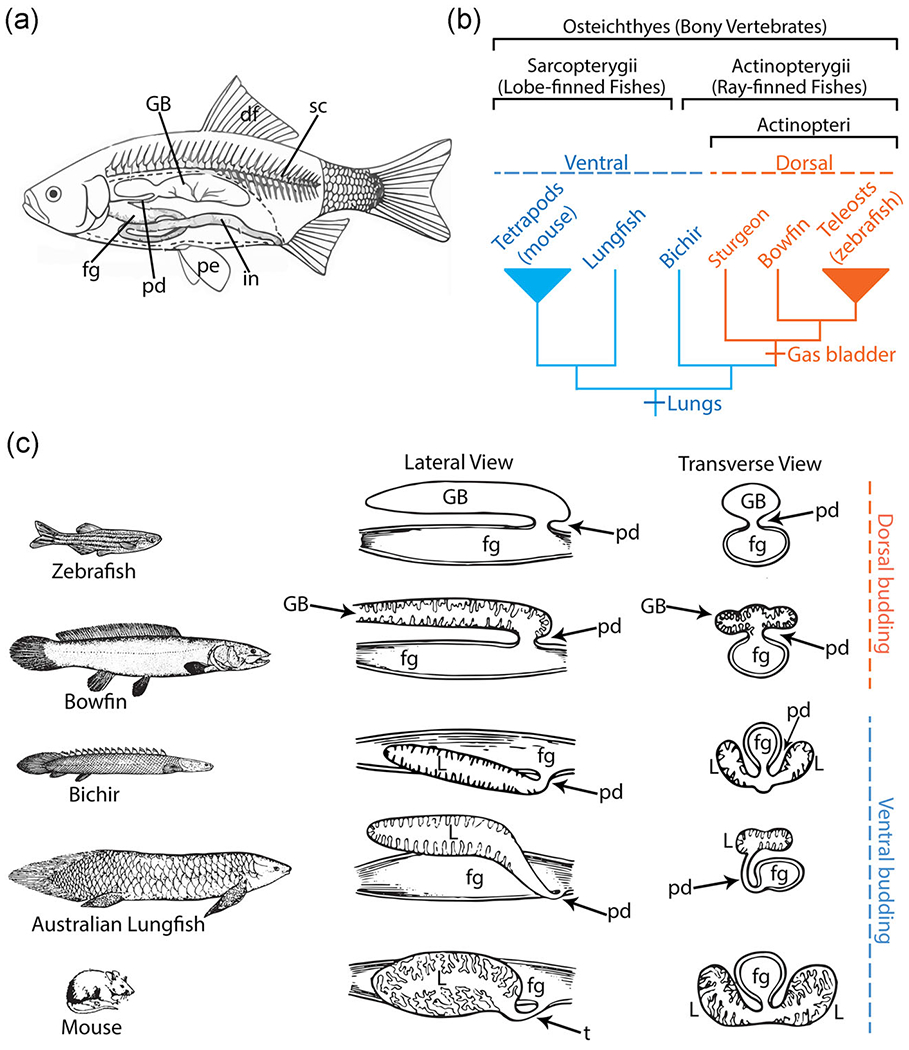

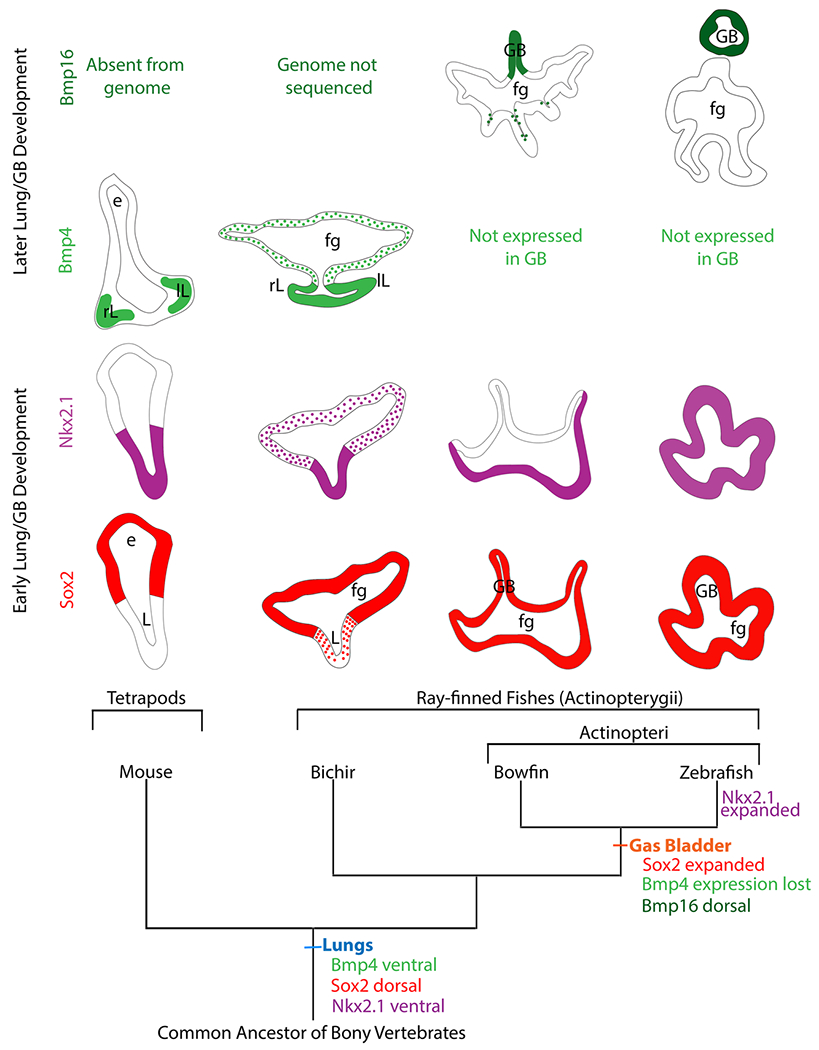

FIGURE 1.

Basic morphology and phylogenetic distribution of lungs and the gas bladder. (a) Diagram of a typical teleost fish showing the dorsal location of the gas bladder situated above the gut and below the spine (Pough, Heiser, & McFarland, 1996). (b) A highly pruned phylogeny of bony vertebrates showing taxa of interest. The two major lineages of the bony vertebrate clade are the lobe-finned fishes (about 30,500 species), which includes tetrapods (e.g., mouse), and the ray-finned fishes (over 30,000 species; Nelson et al., 2016). Within the ray-finned fishes, bichirs are the only ray-finned fish that possess lungs (blue), while bowfin and teleosts possess a gas bladder (orange). Based on phylogenetic distribution of air-filled organs, the lungs are the ancestral state for the bony vertebrates and the gas bladder originated in the lineage containing bowfin and teleosts (e.g., zebrafish). (c) Dorsal versus ventral outgrowth of lungs and gas bladders in key taxa. Taxa are illustrated in the left column. To the right of each organism, in the middle column, is a line drawing showing a lateral view of the dissected foregut and lungs/gas bladder (after Dean, 1895). In the right-most column, a transverse-sectional schematic of the foregut and lungs or gas bladder is shown (after Dean, 1895). As shown, zebrafish and bowfin have a dorsally budding gas bladder. Bichir, Australian lungfish, and mouse have ventrally budding lungs. df, dorsal fin; fg, foregut; GB, gas bladder; in, intenstine; L: lungs; pd, pneumatic duct; pe, pectoral fin; sc, spinal cord; t, trachea

To probe the underlying differences in gene expression between the dorsal budding of gas bladders and ventral budding of lungs, we focus on three important representative fish taxa, bichir, bowfin, and zebrafish. Bichir and bowfin are living ray-finned fish taxa that diverged before and after the origin of the gas bladder, respectively (Figure 1b). Bichirs are the only living ray-finned fish retaining ventrally budding lungs (Figure 1b,c) and thus represent the ancestral condition of bony vertebrates. Within the actinopterygian fishes, the bichirs are the sister-group to all other ray-finned fishes (Actinopteri) including sturgeon, bowfin, and zebrafish (Figure 1b). Bowfin diverged after gas bladder origination and represent the sister clade to teleosts (including zebrafish), the dominant group of living fishes. In bowfin, the connection between the gut and gas bladder, the pneumatic duct, persists, and the gas bladder has elaborated surface area and vascularization, important for its respiratory function (Graham, 1997). Zebrafish is a more recently diverged teleost species with a two-chambered gas bladder and a persistent pneumatic duct (Finney, Robertson, McGee, Smith, & Croll, 2006).

Here we investigate whether the morphological inversion of the budding site is associated with ventral-to-dorsal inversion in the expression pattern of genes known to regulate lung development. We used immunofluorescence (IF) to compare the expression patterns of key candidate genes in our three focal taxa, bichir, bowfin, and zebrafish. Given the homology between the lungs and the gas bladder, we hypothesized that the genes regulating lung development might also regulate gas bladder formation but via different patterns of spatial and temporal expression. We first focused on two essential transcription factors, Sox2 and Nkx2.1, because they show opposing dorsal-ventral expression patterns in developing mouse lungs (Figure 2). We predicted that (1) in bichir, the only living ray-finned fish that retains lungs, Nkx2.1 and Sox2 would exhibit the same foregut expression pattern seen in mouse, and (2) in bowfin and zebrafish which have gas bladders, we would observe an inverted expression pattern of Nkx2.1 and Sox2 relative to mouse lungs. We also examined the expression patterns of Bmp4, known to play a role in lung budding and branching, and Bmp16, a paralog of Bmp4 present in ray-finned fishes but absent from mammalian genomes. We hypothesized that in bichirs, which possess ventrally budding lungs, Bmp4 would be expressed ventrally in the lung buds similar to the pattern during mouse lung development. In bowfin, which has a gas bladder, we hypothesized that Bmp16 (rather than Bmp4) would be expressed dorsally in the gas bladder bud.

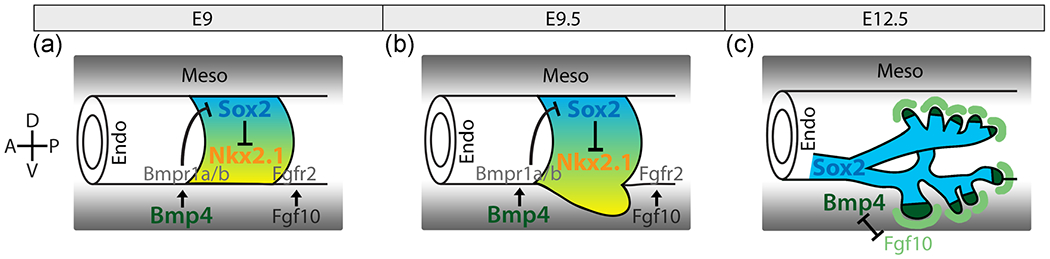

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of known gene interactions regulating lung development. (a) At embryonic day 9 (E9) in mouse, the lung field is established. (b) At E9.5, the nascent lungs bud ventrally from the anterior foregut. During these early stages of lung development, E9 and E9.5 (a and b), Nkx2.1 (yellow), the first marker of lung develoment, is expressed ventrally in the foregut endoderm and indicates the site of lung budding. Sox2 (blue) is expressed dorsally in the foregut endoderm and is mutually inhibitory with Nkx2.1. Bmp4 in the mesoderm interacts with its receptors, Bmpr1a and Bmpr1b, in the endoderm to inhibit the expression of Sox2 ventrally allowing for the expression of Nkx2.1. (c) At E12.5, during lung branching, Bmp4 (dark green) becomes expressed at the distal tips of the branching lung buds, and Fgf10 (light green) is expressed in the mesoderm surrounding the distal tips. Bmp4 and Fgf10 interact to promote bud outgrowth and branching. Endo, endoderm; Meso, mesoderm

Surprisingly, we learned that two key genes involved in regulating the ventral direction of lung budding do not appear to regulate the dorsal direction of gas bladder budding and thus do not underlie the morphological shift in budding site. Instead, we find a different gene, Bmp16, to be expressed dorsally in the gas bladder, while Bmp4 is expressed ventrally in taxa (mammals, bichirs) with lungs, suggesting Bmp signaling may play an important role during gas bladder evolution. Collectively, our results shed light on the possible molecular mechanisms responsible for the lung-to-gas bladder evolutionary transition.

1.1 |. Background on gas bladder function and evolution

The gas bladder (also known as the swim bladder or air bladder) is located dorsal to the gut and ventral to the spine (Figure 1a). While a gas bladder persists as a respiratory organ in some bony fishes (e.g. bowfin, gar), in most ray-finned fishes, it functions primarily as a buoyancy organ (Helfman et al., 2009; Steen, 1970). By adding or eliminating oxygen from the gas bladder, a fish can maintain its vertical position in the water column without swimming continuously (Helfman et al., 2009; Steen, 1970). Presumably, the reduction in energy expenditure to maintain vertical position enables greater allocation of energy towards growth, predator avoidance, feeding, and reproduction (Marty, Hinton, & Summerfelt, 1995). Indeed, the gas bladder characterizes the Actinopteri, which includes early diverging sturgeons, paddlefish, gars, and bowfin as well as the Teleostei, the dominant group of living fishes (Figure 1b; Nelson et al., 2016). Within the Teleostei, there are taxa in which the gas bladder is further modified, enhancing varied functions, such as buoyancy in some groups, respiration in others, or even hearing and sound production (Helfman et al., 2009). In deep sea fishes or taxa that migrate vertically through great depths on daily cycles, an air-filled buoyancy organ would be a severe liability; in these taxa, the gas bladder may be lipid-filled, secondarily reduced, or lost (Wittenberg, Copeland, Haedrich, & Child, 1980). The gas bladder, and its modified versions, are clearly important adaptations, critical to the lives of many fishes (Helfman et al., 2009; Marshall, 1971).

The common ancestor of bony vertebrates, that is, ray-finned fishes and lobe-finned fishes, which include tetrapods (Rosen, Forey, Gardiner, & Patterson, 1981; Zimmer & Emlen, 2013), possessed lungs that were used for aerial respiration (Bray, Potts, Milner, Chaloner, & Lawson, 1985; Clack, 2007). Secondarily, air in these early lungs would have also provided buoyancy, keeping the fishes near the surface where they could breathe air (Alexander, 1966; Liem, 1988). In fully aquatic fishes, buoyancy control became an important function of the gas bladder (Alexander, 1966; Liem, 1988). Conversely, in terrestrial bony vertebrates (i.e., tetrapods), the respiratory function of lungs was enhanced for life on land, while the buoyancy control function became largely irrelevant (Liem, 1988).

Lungs and gas bladders in living vertebrates may exhibit a number of morphological and functional differences. For example, mammalian lungs are paired and undergo branching morphogenesis producing bronchi and alveoli (Kardong, 2015). Gas bladders of teleost fishes are usually unpaired and do not branch (Helfman et al., 2009). Functionally, lungs are used for respiration while gas bladders in most fishes function in buoyancy control. However, there are exceptions to these generalizations. Gas bladders can be bilaterally paired (Rice & Bass, 2009), and some tetrapod taxa, such as snakes or caecilians have only a single lung (Wallach, 1998). Gas bladders can be used as supplementary respiratory organs, as in bowfin, gar, and numerous teleosts (Graham, 1997; Liem, 1989). In the context of this diversity of form and function, the key distinguishing characteristic of lungs and gas bladder is the direction of budding from the anterior foregut during development; the gas bladder buds essentially dorsally and the lungs bud essentially ventrally (Figure 1c), though there is variation in the exact positioning of the budding site. For example, the lungs in Australian lungfish (Neoceratodus) connect ventrolaterally to the foregut (Grigg, 1965) and the gas bladder in sturgeon and paddlefish connects dorsolaterally (Grom, 2015). In an aquatic context, a shift of gas bladder budding site to a dorsal position may be functionally important by decreasing the tendency to roll when the fish is not actively swimming (Videler, 1993).

1.2 |. Background on lung and gas bladder development

Extensive research on lung development in the mouse model system has identified many genes involved in regulating development of the mouse respiratory system comprising the trachea and lungs (Hines & Sun, 2014; Kim et al., 2019; Morrisey & Hogan, 2010). Both the trachea and lungs develop from embryonic foregut endoderm. Septation divides the foregut tube into a ventral trachea and dorsal esophagus. Just posterior to the dividing foregut forming the trachea and esophagus, two primary lung buds evaginate from the ventral foregut endoderm (Morrisey & Hogan, 2010; Ornitz & Yin, 2012).

Of the many genes known to regulate lung development (Hines & Sun, 2014; Mariani, Reed, & Shapiro, 2002; Morrisey & Hogan, 2010; Ornitz & Yin, 2012; Rankin et al., 2015), Nkx2.1 is the first molecular marker of mouse lung development. Nkx2.1 is expressed in the ventral foregut endoderm, thus defining the position of future trachea and lung buds. Sox2 is reciprocally expressed relative to Nkx2.1 and is localized in the dorsal foregut endoderm defining the future esophagus (Domyan et al., 2011; Gontan et al., 2008; Minoo, Su, Drum, Bringas, & Kimura, 1999; Que et al., 2007). This same pattern and timing of Sox2 and Nkx2.1 expression is evolutionarily conserved in chicken and Xenopus as well (Ishii, Rex, Scotting, & Yasugi, 1998; Rankin et al., 2015). Deletion of Nkx2.1 in mice causes an expansion of Sox2 expression in the foregut and a failure of the foregut to divide into separate trachea and esophagus resulting in a tracheoesophageal fistula (Minoo et al., 1999; Que et al., 2007). This single tube exhibits strong Sox2 expression characteristic of a normal esophagus showing the loss of ventral identity of the foregut in Nkx2.1-null mice (Minoo et al., 1999; Que et al., 2007). While Nkx2.1-null mice do form ventral lungs, they are smaller in size and do not undergo normal branching morphogenesis resulting in the inability to perform gas exchange and thus postnatal death (Minoo et al., 1999). A conditional knockout of Sox2 in mice also produces a tracheoesophageal fistula; however, the single tube exhibits a ventralized foregut phenotype evidenced by strong Nkx2.1 expression characteristic of a normal trachea (Que et al., 2007). Based on these mouse studies, Nkx2.1 and Sox2 are evidently important for determining dorsoventral identity in the foregut during development of the mouse respiratory system.

Bmp4, a member of the transforming growth factor-β protein superfamily, is involved in establishing the opposing dorsoventral patterns exhibited by Nkx2.1 and Sox2 during lung development in mice (Domyan et al., 2011; Li, Gordon, Manley, Litingtung, & Chiang, 2008). During early lung development at the initial budding stage, mouse embryonic (E) 9.5, Bmp4 is expressed in the ventral mesoderm surrounding the lung bud, where it represses Sox2 expression in the ventral foregut endoderm allowing for expression of Nkx2.1 (Figure 2a; Domyan et al., 2011). Thus, Bmp4 signaling restricts Sox2 expression to the dorsal foregut endoderm, while Nkx2.1 is expressed in the ventral endoderm. When Bmp4 signaling is inhibited during mouse lung development, Sox2 expression expands ventrally and Nkx2.1 fails to be expressed, leading to an undivided foregut exhibiting expression patterns characteristic of the esophagus and extra ectopic lung buds (Domyan et al., 2011; Li et al., 2008). After initial lung budding, during branching morphogenesis, Bmp4 is expressed in the endoderm at the distal tips of the elongating lung branches (Figure 2c; Bellusci, Henderson, Winnier, Oikawa, & Hogan, 1996). Through interaction with Fgf10, expressed in the mesoderm surrounding the branch tips, Bmp4 helps regulate branch elongation and division (Figure 2c). Bmp4 acts to inhibit, while Fgf10 acts to promote branch elongation (Weaver, Dunn, & Hogan, 2000). Bmp4 has been shown to play multiple and dynamic roles throughout mouse lung development, including interacting with Sox2 to establish a dorsoventral pattern across the anterior foregut and determine respiratory system identity, which includes proper lung budding and septation of the trachea and esophagus (Domyan et al., 2011).

To date, Bmp4 has not been shown to play a role in gas bladder development. However, Feiner, Begemann, Renz, Meyer, and Kuraku (2009) discovered the existence of Bmp16, a paralogue of Bmp4 and Bmp2, in genomes of teleost fishes. Since then, Bmp16 has also been identified in coelacanths, lepidosaurs (e.g., snakes and lizards), and chondrichthyans (sharks, skates, and rays). However, Bmp16 has not been found in any known mammalian genomes, including mouse and human (Feiner et al., 2009; Feiner, Motone, Meyer, & Kuraku, 2019; Marques et al., 2016). During zebrafish development, at 3 days postfertilization (dpf), Bmp16 is expressed in the anterior foregut as well as in the gas bladder. Subsequently, at 5 dpf, Bmp16 is strongly expressed in the gas bladder (Feiner et al., 2009). Marques et al. (2016) also showed that zebrafish Bmp16 is highly similar in both amino acid sequence and tertiary protein structure to Bmp2 and Bmp4 and can activate Bmp-signaling pathways, suggesting Bmp16 may play a similar role in gas bladder development as Bmp4 plays during lung development. Moreover, prdc, a known antagonist of both Bmp2 and Bmp4, is also expressed during gas bladder development in zebrafish (Feiner et al., 2009). Later in mouse lung development, during branching morphogenesis, gremlin, a Bmp4 antagonist, interacts with Bmp4 to pattern the proximal-distal axis. The expression of antagonistic protein prdc in the gas bladder suggests a similar interaction between Bmp16 and prdc may promote gas bladder development and outgrowth (Feiner et al., 2009).

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Egg collection and sampling

We collected bowfin eggs from Oneida Lake, NY during the spawning season in May. The eggs were immediately treated with methylene blue to prevent fungal growth and transported to our lab at Cornell University. The eggs and larvae were raised at 15°C in water from Oneida Lake. Water changes were done every other day, and the water was treated at each water change with methylene blue until hatching. We sampled 20–30 larvae daily between Days 0 to 12 posthatching to capture bowfin development between Stages 23 and 28 (Ballard, 1986). We followed Ballard’s (1986) staging series to track bowfin gas bladder development: Stage 24 is just before gas bladder budding, Stage 25 is at initial gas bladder budding, Stage 26 is right after budding, and Stages 27 and 28 are during gas bladder outgrowth. Representative specimens for each stage were deposited in the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, CU# 99737-99740.

Bichir and zebrafish were spawned in captivity. We received bichir eggs from a private aquarist and reared the eggs and larvae in 26.6°C freshwater (0.05–0.1 parts per thousand) in the laboratory. Water was changed every other day. Until hatching, the water was treated with methylene blue to prevent fungal growth on the eggs. We sampled 10–20 larvae per day from 7 to 13dpf, which spanned bichir Stages 30 to 37 following Budgett (1902) to track bichir lung development: Stage 32 is just before lung budding, Stage 33 is at initial lung budding, Stage 34 is right after lung budding, and Stages 35 and 36 are during lung outgrowth. Representative specimens for each stage were deposited in the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates, CU# 99741-99744.

Twenty zebrafish larvae were sampled per day between 2 and 5 dpf obtained from a laboratory stock of wild-type adults reared at standard conditions in the Fetcho Lab at Cornell University. In zebrafish, the gas bladder bud forms at 2 dpf (pharyngula stage). Zebrafish were reared at standard conditions.

All sampled larvae were euthanized with an overdose of MS-222 and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The samples were then flash frozen in 2:1 Tissue Tek optimal cutting temperature compound: 30% sucrose embedding medium in a 2-methylbutane bath with liquid nitrogen. Embedded samples were stored at −80°C. Samples were sectioned into 15-μm sections using a cryostat (Leica CM 1950) and mounted on Fisher SuperFrost Plus microscope slides for IF or RNAscope (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). All animal protocols and procedures were performed in accordance with IACUC (protocol #2006-0013).

2.2 |. Immunofluorescence

We used fluorescent IF to observe the expression patterns of Sox2, Bmp4, and Bmp16 in all three species as well as the expression patterns of phospho-Smad1/Smad5/Smad9 (pSmad) to determine Bmp activity. We followed standard protocol for IF on sections (Welsh et al., 2013). Primary antibodies include rabbit anti-Sox2 (1:500; My Bio Source MSB9127841), rabbit anti-Bmp4 (1:100; My Bio Source MSB9417271), rabbit anti-Bmp16 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pierce Biotechnology), and phospho-Smad1 (Ser463/465)/Smad5 (Ser463/465)/Smad9 (Ser465/467) (D5B10) Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling Technology). No commercial Bmp16 antibodies were available, so the rabbit anti-Bmp16 antibody was designed and produced by Pierce Biotechnology (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a bowfin Bmp16 antigen (sequence: DQRGVDSSRLARLE). The Bmp16 antibody was designed not to cross react with Bmp4 or Bmp2 (Figure S1); to verify specificity, we performed IF with the rabbit anti-Bmp16 antibody in mouse. Because mammal genomes do not have a Bmp16 gene, we should not observe any fluorescent signal by rabbit anti-Bmp16 antibody in mouse tissues. Secondary antibodies used include Alexafluor 568 goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) or Alexafluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500; Life Technologies). pSmad samples were visualized with a biotinylated secondary (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch), followed by a streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and then tyramide amplification was performed following the TSA Plus Cy3 protocol (1:50; Perkin-Elmer). We colabeled with DAPI (1:1000) to visualize all cell nuclei to provide morphological context. To visualize the fluorescently labeled expression patterns, we used a Zeiss Observer.Z1/ApoTome.2 inverted microscope with AxioCam HRc camera.

As a negative control for the binding specificity of the rabbit anti-Sox2 antibody in bichir, bowfin, and zebrafish, we monitored signal in the pectoral fin tissue, in which Sox2 should not be expressed. We observed no nonspecific binding of the Sox2 antibody in the pectoral fin of bichir, bowfin, or zebrafish. As a positive control, we observed binding of the Sox2 antibody in the ventricular zone of the brain, a region of strong Sox2 expression (Bani-Yaghoub et al., 2006), in all study species. The positive tissue-control for the rabbit anti-Bmp4 antibody included expression in the pectoral fins and inner ear.

2.3 |. RNAscope in situ hybridization

We performed RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Assay to observe the RNA expression patterns of Nkx2.1 during development of bowfin gas bladder and bichir lungs and of Nkx2.1b during development of zebrafish gas bladder. Nkx2.1b is one of two copies of the gene in zebrafish due to the teleost whole genome duplication event. Previously, Cass et al. (2013) found both Nkx2.1 paralogues to be expressed during gas bladder development in zebrafish; however, Nkx2.1b was only expressed dorsally in the gas bladder bud. Advanced Cell Diagnostics designed species-specific RNA probes for Nkx2.1 for each of the three taxa. We used the RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent v2 Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) with the Perkin Elmer Cy3 fluorophore. Fluorescent images were captured with a Zeiss Observed.Z1/ApoTome.2 inverted microscope with AxioCAM HRc camera. Nkx2.1 is expressed only in the foregut, the gas bladder, the thyroid, and the forebrain of zebrafish. As a negative control for the binding specificity of the RNAscope Nkx2.1 probes, we observed no fluorescent signal in any other tissues during the development of our three study species. We did observe binding of the Nkx2.1 probe, as expected, in the diencephalon and telencephalon of the forebrain (González, López, & Marín, 2002).

2.4 |. Bmp16 phylogeny

To document the paralogy and evolutionary history of bowfin Bmp2, Bmp4, and Bmp16, we reconstructed a gene tree for these three genes using sequences from Feiner et al. (2019) plus the bowfin sequences. The outgroups used in the analysis were Xenopus, chicken, opossum, human, and sea lamprey. We aligned the protein sequences in MAAFT according to the default settings (Katoh, Rozewicki, & Yamada, 2019). We then used IQ-TREE Web Service with ultrafast bootstrap and model selection to reconstruct the gene tree according to default settings and enabling the FreeRate heterogeneity model (Chernomor, von Haeseler, & Minh, 2016; Hoang, Chernomor, von Haeseler, Minh, & Vinh, 2018; Kalyaanamoorthy, Minh, Wong, von Haeseler, & Jermiin, 2017; Trifinopoulos, Nguyen, von Haeseler, & Minh, 2016). The resulting tree was viewed in FigTree v1.4.4 and rooted on sea lamprey bmp paralogues.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Dorsal–Ventral expression of Sox2 and Nkx2.1

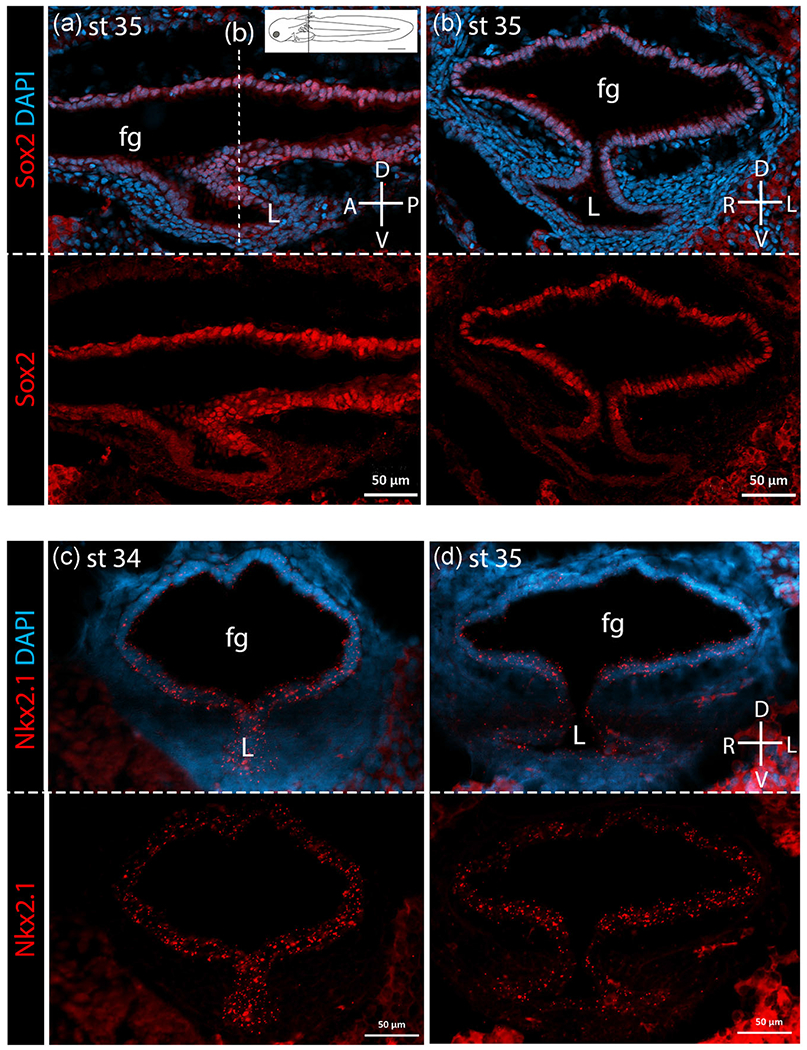

We hypothesized that in the developing lungs of bichir, Sox2 would be expressed dorsally, and Nkx2.1 would be expressed ventrally, as in mouse (Domyan et al., 2011; Morrisey & Hogan, 2010). As expected, we found that Sox2 was expressed in the dorsal foregut endoderm opposite the lung budding site and it was absent from the ventral lung bud and lungs proper at all stages (Figure 3a,b). As in mouse (Lazzaro, Price, Felice, & Lauro, 1991; Morrisey & Hogan, 2010), Nkx2.1 is expressed strongly in the ventral foregut endoderm of bichir at all stages analyzed. However, unlike mouse, where Nkx2.1 is restricted ventrally, in bichir, Nkx2.1 is expressed in a gradient with weaker expression dorsally in the foregut (Figure 3c,d). During early lung development (Stages 33 and 34) in bichirs, Nkx2.1 is also strongly expressed in the lung bud (Figure 3c), but later in development, during outgrowth (Stages 35 and 36), Nkx2.1 expression weakens in the lungs compared to the ventral foregut (Figure 3d).

FIGURE 3.

Sox2 and Nkx2.1 expression in bichir lungs. For each pair of panels, the top panel shows gene expression in bright red overlain by bright blue DAPI staining of cell nuclei. Bottom panels show gene expression alone in bright red. Compasses indicate orientation of sections. (a) Sagittal section of Sox2 expression in the foregut and lungs at stage 35 during outgrowth. The position of the transverse section is marked on the sagittal section (dotted line) and on the inset diagram of a larval bichir. (b) Sox2 expression in the lungs at Stage 35 is shown in transverse section. These sections show that Sox2 is expressed throughout the foregut (fg) but absent from the lung buds (L). (c) Nkx2.1 expression at Stage 34, right after lung budding. At Stage 34, Nkx2.1 is expressed throughout the foregut (fg) and lung bud (L) but strongest expression is in the ventral foregut and lung bud. (d) Nkx2.1 expression at Stage 35, during lung outgrowth. At Stage 35, Nkx2.1 continues to be expressed throughout the foregut and lungs with strongest expression in the ventral foregut and weaker expression in the dorsal foregut and lungs. A, anterior; D, dorsal; L, left; n, notochord; P, posterior; R, right; V, ventral

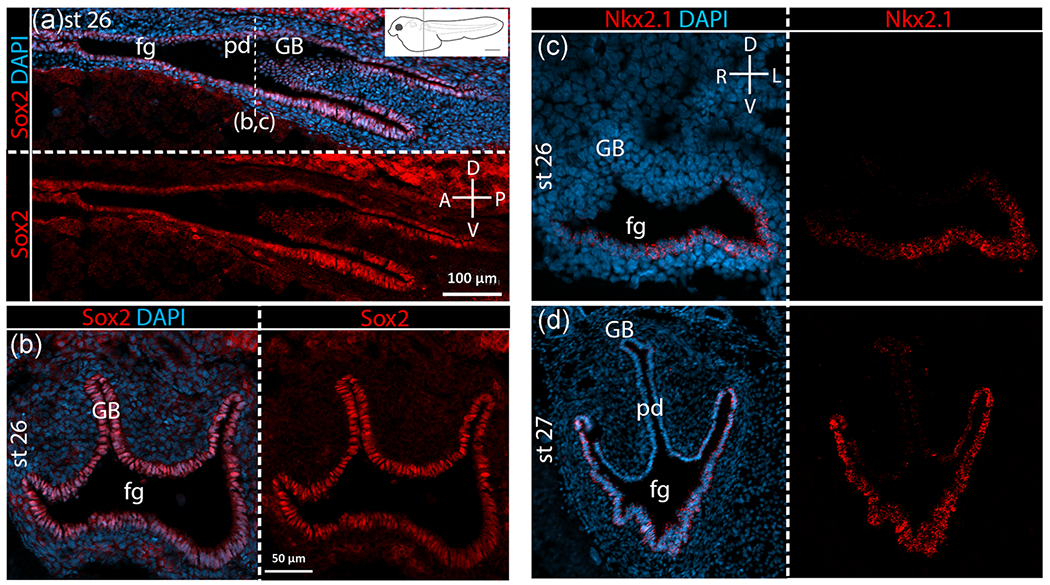

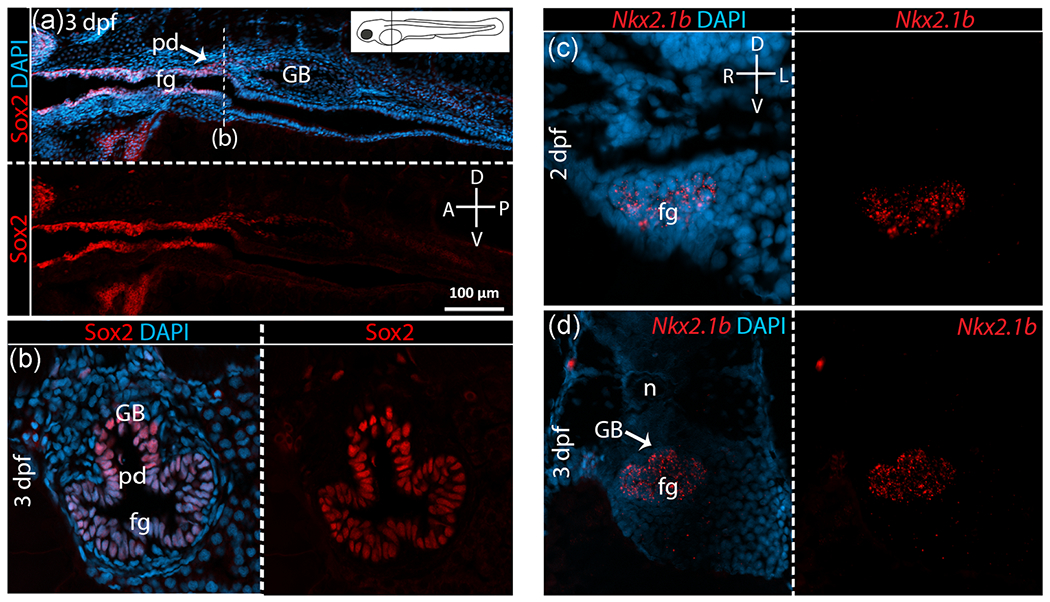

Given the dorsoventrally inverted location of budding of the gas bladder relative to lungs, we hypothesized an inverted pattern of gene expression relative to lung development. Thus, in taxa with gas bladders we predicted ventral expression of Sox2 and dorsal expression of Nkx2.1. However, contrary to expectation, Sox2 is expressed throughout the foregut endoderm, both ventrally and dorsally, as well as in the gas bladder bud itself at all stages examined in both bowfin (Figure 4a,b) and zebrafish (Figure 5a,b). Sox2 expression in the gastrointestinal tract varies along the anteroposterior body axis differently in these two taxa with gas bladders. In bowfin, Sox2 is expressed all along the anteroposterior axis of the gut and in the gas bladder proper at all stages examined (Figure 4a). In zebrafish, after the gas bladder has inflated (3dpf), Sox2 expression occurs only in the anterior foregut endoderm continuing posteriorly up to the pneumatic duct, which connects the gas bladder to the foregut. Sox2 is also expressed in the pneumatic duct itself as well as in the walls of the gas bladder (Figure 5a). At all stages examined during bowfin gas bladder development, Nkx2.1 is highly expressed in the ventral foregut endoderm (Figure 4c,d), as observed in mouse lung development. Nkx2.1 is not expressed in the dorsal foregut or pneumatic duct but shows weak expression in the gas bladder itself during outgrowth (Stage 27; Figure 4d). In zebrafish, Nkx2.1b is expressed in the gas bladder bud and throughout the foregut endoderm at budding and outgrowth stages (Figure 5c,d).

FIGURE 4.

Sox2 and Nkx2.1 expression in bowfin gas bladder. For each pair of panels, the top or left panel shows gene expression in bright red overlain by bright blue DAPI staining of cell nuclei. Bottom or right panels show gene expression alone in bright red. Compasses indicate orientation of sections. (a) Sox2 expression in sagittal view in bowfin at Stage 26, right after gas bladder budding. The position of the transverse section is marked on the sagittal section (dotted line) and on the inset diagram of a larval bowfin. (b) Sox2 expression at Stage 26 displayed in transverse section. As shown, Sox2 is expressed throughout the foregut (fg) and the gas bladder bud (GB), and expression extends beyond the pneumatic duct (pd) connection to the foregut. (c) Nkx2.1 expression at Stage 26, right after gas bladder budding shows clearly the ventrally restricted expression of Nkx2.1 in the foregut and absence of Nkx2.1 expression in the gas bladder bud. (d) Nkx2.1 expression at Stage 27, during gas bladder outgrowth showing strong Nkx2.1 expression ventrally in the foregut as well as very weak expression in the gas bladder. A, anterior; D, dorsal; L, left; n, notochord; P, posterior; R, right; V, ventral

FIGURE 5.

Sox2 and Nkx2.1 expression in zebrafish gas bladder. For each pair of panels, the top or left panel shows gene expression in bright red overlain by bright blue DAPI staining of cell nuclei. Bottom or right panels show gene expression alone in bright red. Compasses indicate orientation of sections. (a) Sagittal view of Sox2 expression in zebrafish at 3 dpf, right after gas bladder budding. The position of the transverse section is marked on the sagittal section (dotted line) and on the inset diagram of a larval zebrafish. (b) Sox2 expression at 3 dpf shown in transverse section. As shown, Sox2 is expressed throughout the foregut (fg) and the gas bladder bud (GB). However, Sox2 expression is absent from the gut beyond the pneumatic duct (pd). (c) Nkx2.1b expression in zebrafish at 2 dpf, initial gas bladder budding. (d) Nkx2.1 expression at 3 dpf, right after budding. Nkx2.1b expression is expanded to the entire foregut and the gas bladder bud. A, anterior; D, dorsal; L, left; n, notochord; P, posterior; R, right; V, ventral

3.2 |. Roles of Bmp genes in bichir, bowfin, and zebrafish

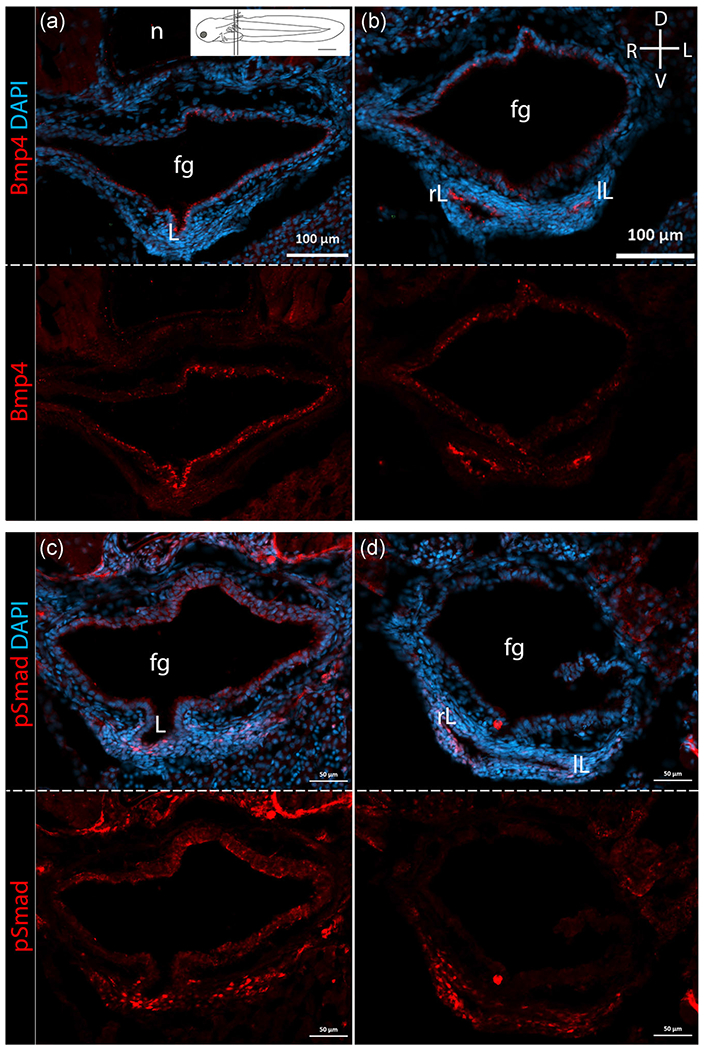

In mouse, Bmp4 is expressed in the mesenchyme surrounding the ventral foregut before and during initial lung budding and also in the distal epithelium during lung outgrowth and bifurcation (Morrisey & Hogan, 2010; Ornitz & Yin, 2012; Que, Choi, Ziel, Klingensmith, & Hogan, 2006). Thus, we hypothesized that Bmp4 expression in bichir lungs would be similar to its expression in mouse lungs. We find the temporal expression of Bmp4 in bichir is indeed similar to that in mice, but the spatial expression differs. Bmp4 is expressed at the time of initial lung budding in both bichir (Stage 33) and mice. However, in bichir, Bmp4 is expressed strongly in the endoderm of the lung bud rather than the surrounding mesenchyme. In bichir, Bmp4 continues to be expressed in the lung epithelium during lung outgrowth (Stage 35) but expression is not restricted to the distal tips as it is in mouse lungs (Figure 6a,b). Canonical BMP signaling results in intracellular phosphorylation of regulatory Smads1/5/9. Confirming Bmp activity, we detected Smad phosphorylation in the ventral mesenchyme surrounding the lung buds, where Bmp4 is expressed, during bichir development (Figure 6c,d). In bichir, Bmp4 also shows weak expression in the anterior foregut, ventrally and dorsally, from which the lungs bud, at all stages investigated (Figure 6a,b). Bmp4 expression has not been observed in the foregut or gas bladder during zebrafish development, and likewise, we do not find Bmp4 expression in the foregut or gas bladder of bowfin. However, Bmp4 expression is observed in the inner ear and fin of zebrafish, confirming cross-reaction of the anti-Bmp4 polyclonal antibody (Figure S2c). In bowfin, we observe Bmp4 expression in the pharynx, anterior to the location of gas bladder budding (Figure S2a). However, neither in the foregut at the site of budding nor in the gas bladder of bowfin do we find any Bmp4 expression (Figure S2b).

FIGURE 6.

Bmp4 expression and Smad phosphorylation in bichir lungs. For each pair of panels, top panels shown protein expression in bright red overlain with DAPI in blue. Bottom panels show protein expression alone in bright red. All panels are shown in transverse section, with the compass indicating orientation shown in upper right panel. Inset in panel a shows a diagram of a larval bichir with position of anterior and posterior sections indicated. (a) Bmp4 expression in the anterior region of bichir lungs at Stage 36 during lung outgrowth. (b) Bmp4 expression in the posterior region of the lungs at Stage 36. Bmp4 is expressed in the foregut (fg) and lung endoderm with strong expression in the lungs. (c) Smad phosphorylation, shown in bright red, is detected in anterior region of bichir lungs at Stage 36 during lung outgrowth. (d) Smad phosphorylation is detected in posterior region of the lungs at Stage 36. Smad phosphorylation, indicating Bmp4 activity, is detected strongly in the ventral mesenchyme surrounding the lung buds. D, dorsal; L, left; lL, left lung; R, right; rL, right lung; V, ventral

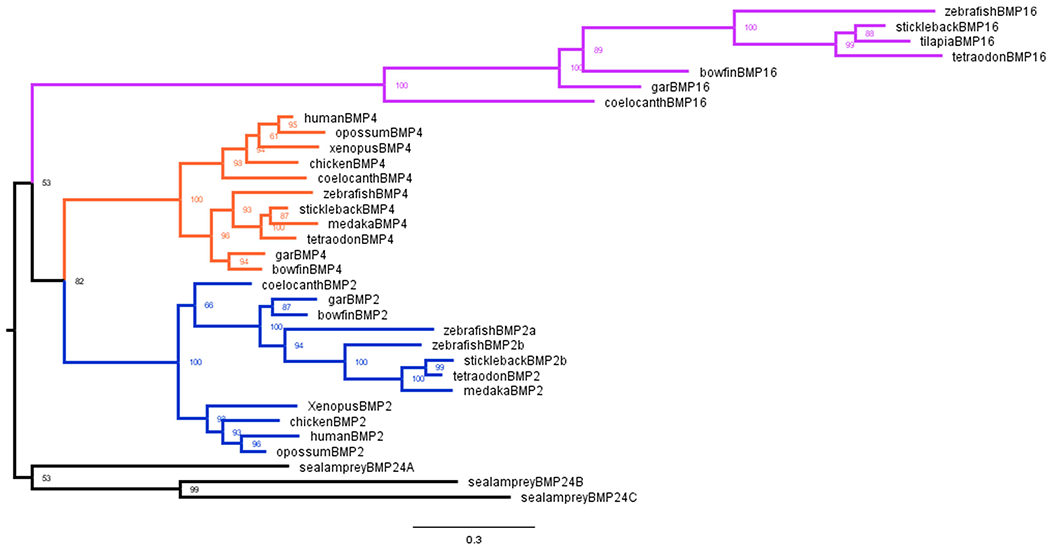

Recently, a Bmp4 paralog, Bmp16, present in multiple ray-finned fish genomes but absent mammalian genomes has been shown to be expressed in the zebrafish gas bladder (Feiner et al., 2009, 2019). Using sequence alignment, we identified a putative Bmp16 gene in the bowfin genome. This putative Bmp16 contained all amino acid residues conserved among previously annotated Bmp16 genes in ray-finned fishes. To confirm that the bowfin Bmp16 we found was an ortholog, we constructed a gene tree for Bmp16, Bmp4, and Bmp2 as described above. Overall, our gene tree (Figure 7) agreed with the tree built by Feiner et al. (2019). The putative bowfin Bmp16 clustered with the other known Bmp16 sequences of various ray-finned fishes (gar, zebrafish, stickleback, tetraodon, and tilapia) as well as with Bmp16 from coelacanth confirming that the gene we identified as Bmp16 in the bowfin genome is an ortholog of Bmp16. Using the protein sequence for bowfin Bmp16 as an antigen, we designed a polyclonal antibody with Pierce Biotechnology (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To test the specificity of this antibody, we performed an IF in mouse using the custom Bmp16 antibody. Our Bmp16 antibody did not react in mouse tissues and showed no expression (Figure S3). Because Bmp16 is absent from mammal genomes, this confirms the specificity of our antibody, and that it does not cross-react with either Bmp4 or Bmp2 (Figure S3).

FIGURE 7.

Bmp16 gene tree. Reconstructed gene tree of relationships of Bmp16, Bmp4, and Bmp2 among bony vertebrates. The Bmp2 cluster is shown in blue. The Bmp4 cluster is shown in orange. The Bmp16 cluster is shown in purple. The sea lamprey Bmp2/4 genes (black) are used as the outgroup. Note that the putative bowfin Bmp16 is nested within the Bmp16 clade

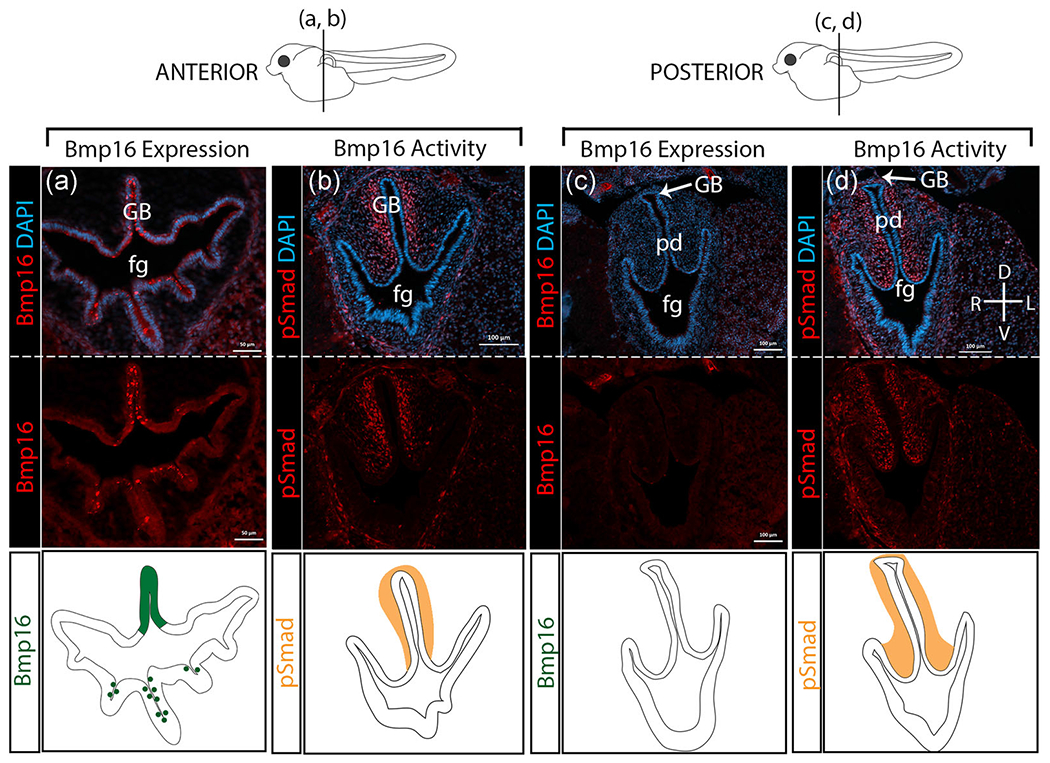

Because Bmp4 is expressed ventrally in the developing mouse lung, and Bmp16 (not Bmp4) is expressed in the developing gas bladder of zebrafish (Feiner et al., 2009), we hypothesized that Bmp16 would be expressed dorsally in the developing gas bladder during bowfin development. Our IF assays first detect Bmp16 expression in the bowfin foregut and gas bladder bud right after initial gas bladder budding (Stage 26). During this developmental stage (Stage 26), Bmp16 is expressed dorsally in the anterior gas bladder, but absent posteriorly (Figure 8a,b). Bmp16 expression appears to be strongest during gas bladder outgrowth (Stages 27 and 28) as shown by very bright fluorescent staining in the anterior gas bladder and pneumatic duct. Bmp16 is also expressed in the ventral folds of the foregut at this stage of development (Figure 8a). However, in the posterior regions of the gas bladder, where lateral growth of the gas bladder occurs, Bmp16 expression is absent (Figure 8b). Concurrent with Bmp16 expression, during gas bladder outgrowth, strong Smad phosphorylation, which demonstrates Bmp activity, is detected in the dorsal mesenchyme surrounding the gas bladder (Figure 8c,d). However, unlike Bmp16, which is not expressed posteriorly in the gas bladder, strong Smad phosphorylation is still detected in the dorsal mesenchyme surrounding the posterior region of the gas bladder (Figure 8d). Although, we cannot rule out the possibility of additional active Bmp’s (Bmp4 or Bmp2) in the gut or gas bladder, the expression of Bmp16 in the endoderm and Smad phosphorylation in the surrounding mesenchyme suggests that Bmp16-signaling plays a role in regulating gas bladder development in bowfin. Overall, expression of Bmp16 during bowfin gas bladder development suggests that Bmp16 was recruited to regulate development during the lung-to-gas bladder evolutionary transition.

FIGURE 8.

Bmp16 expression and Smad phosphorylation in bowfin gas bladder. For each column, top panels show gene expression in bright red overlaid with DAPI in blue. Middle panels show gene expression alone in bright red. The bottom panels depict graphically the gene expression patterns shown as photomicrographs above for Bmp16 (dark green) and pSmad (orange). All panels are transverse sections at Stage 27 during outgrowth. The anterior-posterior location of the transverse sections is indicated on the larval bowfin diagrams shown above the panels. (a) Bmp16 expression in the anterior region of bowfin gas bladder. (b) Smad phosphorylation is detected in the anterior region of the gas bladder. (c) Bmp16 expression in the posterior region of the gas bladder in bowfin. (d) Smad phosphorylation is detected in the posterior region of the gas bladder. Bmp16 is expressed strongly in the anterior gas bladder (GB); however, more posteriorly, where the gas bladder expands laterally, Bmp16 expression is absent. Bmp16 activity, as indicated by Smad phosphorylation, is strong in the dorsal mesenchyme surrounding the gas bladder, both anteriorly and posteriorly. n, notochord; pd, pneumatic duct

3.3 |. Summary of the changes in gene expression during gas bladder evolution

Expression patterns during lung budding and gas bladder budding for the four genes of interest are mapped on a phylogeny in Figure 9 to show the evolutionary changes in dorsoventral expression of these genes in four critical taxa representing major groups of bony vertebrates. Details of the expression patterns of each gene in all taxa are summarized in Table 1. Mouse (representing tetrapods) and bichirs develop ventral lungs, and in both taxa, Sox2 is expressed dorsally in the foregut, opposite the lung budding site. In contrast, in both bowfin and zebrafish, which develop dorsal gas bladders, Sox2 expression is expanded to the entire foregut, dorsally and ventrally. As expected, Nkx2.1 is expressed in the ventral lungs in both mouse and bichir. Surprisingly, in both bowfin and bichir, both early-diverging ray-finned fishes, Nkx2.1 shows strong expression in the ventral wall of the foregut despite that bowfin have a gas bladder and bichir have lungs. In zebrafish, which are nested within the teleost clade, Nkx2.1b expression is expanded beyond the ventral wall of the associated foregut dorsally into the gas bladder bud. The spatial expression patterns of Nkx2.1 and Sox2 during gas bladder development do not support the hypothesis that these genes contribute to regulating the direction of gas bladder budding.

FIGURE 9.

Gene expression changes during the lung-to-gas bladder transition in ray-finned fishes. Using a pruned bony-vertebrate phylogeny as an evolutionary framework, expression patterns of Sox2 (red), Nkx2.1 (purple), Bmp4 (light green), and Bmp16 (dark green) are shown for transverse sections of the foregut and either lungs or gas bladder of each taxon. Expression of Nkx2.1 and Sox2 are conserved for mouse and bichir. Bmp4 is expressed in the lung endoderm during outgrowth of both lungs and gas bladder, but Bmp4 is restricted to the distal tips of lung branch in mouse and not bichir. Expression of Sox2 is expanded in taxa with gas bladders (bowfin, zebrafish) relative to taxa with lungs (mouse, bichir). Expression of Nkx2.1 is expanded in taxa with gas bladders (bowfin, zebrafish) relative to taxa with lungs (mouse, bichir). Bmp16, rather than Bmp4 is expressed in taxa with gas bladders. Hypothesized expression patterns in the common ancestor of bony vertebrates, inferred from shared patterns between bichir and tetrapods, are indicated at the base of the phylogeny. The zebrafish gas bladder is connected to the foregut, but the pneumatic duct is not shown in the Bmp16 image because the section is posterior to the pneumatic duct. fg, foregut; GB, gas bladder; L,

TABLE 1.

Summary of expression patterns of four genes during early budding and organ outgrowth of lung or gas bladder development

| Sox2 | Nkx2.1 | Bmp4 | Bmp16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early development (budding) | ||||

| Mouse | Dorsal foregut endoderm; absent from lung bud | Ventral foregut endoderm; lung bud | Ventral mesoderm surrounding lung buds | Absent from genome |

| Bichir | Dorsal foregut endoderm; absent from lung bud | Strong expression in ventral foregut endo; lung bud; weaker in dorsal foregut endoderm | Lung bud endoderm | Unknown, genome not sequenced |

| Bowfin | Entire foregut endoderm; gas bladder bud | Ventral foregut endoderm | Not expressed | Not expressed |

| Zebrafish | Entire foregut endoderm; gas bladder bud | Entire foregut endoderm; gas bladder bud | Not expressed | Not expressed |

| Later development (outgrowth) | ||||

| Mouse | Proximal stalks of lung branches | Lung epithelial cells | Distal tips of lung branches | Absent from genome |

| Bichir | Dorsal foregut endoderm; absent from lungs | Strong in ventral foregut endoderm; weaker in the lungs | Lung endoderm; activity in ventral mesoderm (pSmad) | Unknown, genome not sequenced |

| Bowfin | Entire foregut endoderm; pneumatic duct; gas bladder; posterior gut | Ventral foregut endoderm; very weakly in gas bladder | Not expressed | Anterior gas bladder; activity in dorsal mesoderm (pSmad) |

| Zebrafish | Entire foregut endoderm up to and including pneumatic duct; in the gas bladder but not posterior gut | Entire foregut endoderm; gas bladder bud | Not expressed | Gas bladder |

We found that Bmp4 is highly expressed ventrally in the lungs during lung outgrowth in bichir as well as in mouse. Our Bmp expression data for bowfin are consistent with findings in zebrafish (Feiner et al., 2009). In both bowfin and zebrafish, Bmp4 is absent, but its paralogue, Bmp16 was found to be highly expressed dorsally in the gas bladder during outgrowth. This inverted expression pattern of paralogous Bmp genes suggests that Bmp expression plays a significant role in the morphological inversion of budding direction. As yet, Bmp16 has not been observed during lung development due to the loss of Bmp16 from mammal genomes. Because the bichir genome has not been sequenced, the presence or absence of the Bmp16 gene is unknown.

4 |. DISCUSSION

During the lung-to-gas bladder evolutionary transition along the ray-finned fish lineage, the developmental budding direction shifted from ventral to dorsal. We hypothesized that the underlying gene expression patterns regulating gas bladder development would also show a dorsoventral inversion compared with the patterns regulating lung development (see Funk, Lencer, & McCune, 2020). Instead, we found a more complicated pattern of conserved gene expression in taxa with lungs, modified (but not inverted) expressionn of Nkx2.1 and Sox2 in taxa with gas bladders, and a newly discovered role in gas bladder development for Bmp16, a gene not present in tetrapods.

4.1 |. Conserved gene expression patterns between bichir and tetrapod lung development

Our result showing similar dorsoventral patterning of key regulatory genes, Sox2, Nkx2.1, and Bmp4, in the foregut and lungs of both a fish (bichir) a mouse may seem surprising from a developmental perspective. However, this similarity is expected from an evolutionary perspective. The bichir has retained the primitive lung condition shared by the common ancestors of fishes and tetrapods (including mouse), and it is not surprising that the underlying regulatory networks would be conserved to some degree. Experimental evidence shows that dorsal Sox2 expression functions to restrict the budding location of lungs to the ventral wall of the foregut in mice (Domyan et al., 2011); therefore, the strong expression of Sox2 in the dorsal foregut endoderm in bichir suggests Sox2 may also be involved in restricting the ventral location of lung budding in bichir. Having a dorsally restricted Sox2 expression pattern in the foregut during lung development is consistent across a wide range of bony vertebrates with lungs, including mouse, chicken, Xenopus, and bichirs (Ishii et al., 1998; Que et al., 2007; Rankin et al., 2015). During mouse lung development, Nkx2.1 has a reciprocal expression pattern compared to Sox2 and is expressed in the ventral foregut endoderm and lung buds. Though Nkx2.1 is not completely restricted to the ventral foregut endoderm during bichir lung development as it is in mouse, our data show Nkx2.1 to be expressed in a gradient with strong expression ventrally and weaker expression dorsally across the foregut. In addition, we find Nkx2.1 to be expressed during early lung development in bichir, right after initial budding (Stage 34). Our results show an earlier expression of Nkx2.1 than found by Tatsumi et al. (2016), who observed Nkx2.1 be weakly expressed throughout the bichir foregut and in the lungs no earlier than 12 dpf. This corresponds to lung outgrowth (Stage 36) by our calibration to Budgett’s staging series (1902) based on the morphology of transverse sections. Conserved expression of Sox2 and Nkx2.1 across the dorsal-ventral axis of the foregut during early lung development in bichir and mouse suggest these genes may have regulated the development of primitive lungs in the common ancestor of bony vertebrates.

During the development of the respiratory system in mouse, BarX1 expression regulates the dorsoventral expression of Sox2 and Nkx2.1 across the foregut by repressing Wnt signaling. When BarX1 is knocked out in mouse, Nkx2.1 expression expands, and Sox2 expression is reduced in the foregut, while morphologically, the foregut fails to separate into the esophagus and trachea but the lungs appear to bud normally (Woo, Miletich, Kim, Sharpe, & Shivdasani, 2011). During normal bichir development, the foregut does not separate into an esophagus and trachea but remains a single tube. Given the role of BarX1 in mouse lung development, it would be interesting to know what role it plays in gas bladder development. Perhaps, BarX1 is not expressed in the mesenchyme surrounding the dorsal foregut of bichir allowing Nkx2.1 expression to expand dorsally.

In bichir, Bmp4 shows the expected ventral expression pattern in the developing lung buds similar to the observed pattern in mice. Lung development in mice involves a complex interaction of genes both within and between the foregut endoderm and surrounding mesenchymal tissues (Hines & Sun, 2014; Ornitz & Yin, 2012), and it would be interesting to know to what extent these gene interactions are also conserved. During early lung development in mice, Bmp4 contributes to establishing the ventral budding site of the lung buds. Bmp4 is expressed in the ventral mesenchyme surrounding the future trachea and lung buds in mice and appears to regulate Nkx2.1 expression in the ventral foregut by signaling to the endoderm and repressing Sox2 expression (Figure 2; Domyan et al., 2011; Herriges & Morrisey, 2014; Hines & Sun, 2014; Li et al., 2008). During early lung development in bichir, Bmp4 is expressed ventrally in the lung epithelium rather than in the surrounding mesenchyme as in mouse. In addition, Smad phosphorylation is detected in the ventral mesenchyme surrounding the lung buds in bichir providing evidence that though Bmp4 is expressed in the lung epithelium, it may be signaling to the surrounding mesenchyme. Based on the expression patterns, the genes involved in bichir and tetrapod lung development may be conserved. However, Bmp signaling appears to occur in opposite directions during bichir compared to mouse lung development suggesting that the interactions between Bmp4, Sox2, and Nkx2.1 may differ.

4.2 |. Inversion of Sox2 and Nkx2.1 expression does not underlie the inversion of the budding direction

We did not find an inverted pattern of Sox2 and Nkx2.1 expression in gas bladders relative to the dorsal Sox2 and ventral Nkx2.1 expression in the lungs. Instead, the dorsal–ventral expression pattern of these two genes in the bowfin gas bladder was similar to the pattern in mouse but with Sox2 showing an expanded expression pattern in the foregut (Figure 4). In zebrafish, expression of both Sox2 and Nkx2.1b are expanded dorsoventrally in the foregut during gas bladder development relative to lung development (Figure 5). Previously, using in situ hybridization, Cass et al. (2013) found Nkx2.1b expression to be restricted dorsally to the gas bladder bud during zebrafish development. However, expression of Nkx2.1b was not detected until 4 dpf, 2 days after gas bladder budding at 2 dpf (Cass et al., 2013). Using RNAscope in situ hybridization, we were able to detect the expression of Nkx2.1b in the foregut and gas bladder bud of zebrafish as early as 2 dpf, the period of initial gas bladder budding. Thus, Nkx2.1 is expressed ventrally during the earliest stages of gas bladder development similar to both the spatial and temporal expression of Nkx2.1 during lung development.

In mice, Nkx2.1 plays a significant role in branching morphogenesis as evidenced by Nkx2.1-null mutant mice, which still develop lungs albeit with greatly reduced airway branching (Minoo et al., 1999; Que et al., 2007). This sac-like morphology of mutant lungs is reminiscent of a normal gas bladder (Cass et al., 2013). The expression of Nkx2.1 in the ventral foregut during both early lung and early gas bladder development suggests that ventral Nkx2.1 expression was also present in the foregut of the common ancestor of bony vertebrates, though its function in regulating the development of primitive lungs is unknown. Neither the lungs of bichir (a proxy for primitive bony vertebrate lungs) nor gas bladders of ray-finned fishes undergo branching, but perhaps the presence of Nkx2.1 expression allowed for co-option of Nkx2.1 to regulate lung branching morphogenesis in early terrestrial vertebrates which relied on increasingly branching structures advantageous for aerial respiration.

4.3 |. Role of Bmp16 in gas bladder development

Bmp16, rather than its paralogue Bmp4, is expressed during gas bladder development in zebrafish (Feiner et al., 2009). Bmp16 is also present in the genomes of all other ray-finned fishes investigated thus far (including spotted gar, stickleback, tilapia, green spotted pufferfish, and Takifugu rubripes), but it has been lost from mammalian genomes (Feiner et al., 2009, 2019). In this study, we identified the Bmp16 ortholog in the bowfin genome and found it to be expressed in the epithelium of the anterior gas bladder with the strongest expression at outgrowth, Stages 27 and 28. In addition, Smad phosphorylation detected in the dorsal mesenchyme surrounding the gas bladder bud suggests that Bmp16 ligands are active in the dorsal mesenchyme. This dorsal pattern of Smad phosphorylation and Bmp16 activity is inverted compared to the ventral Bmp4 expression during lung development in mouse and bichir. When compared to the temporal pattern of Bmp4 expression during lung development (Domyan et al., 2011; Weaver et al., 2000), the expression of Bmp16 during gas bladder development in bowfin is delayed. This delay in Bmp16 expression suggests that unlike Bmp4, Bmp16 is not acting upstream to regulate the dorsoventral patterns of Nkx2.1 and Sox2 by repressing Sox2 expression dorsally during gas bladder development. Unlike the spatial pattern of Bmp4 during lung branching morphogenesis (Morrisey & Hogan, 2010), in the bowfin gas bladder, which grows distally and laterally into a “T” shape rather than branching, Bmp16 expression does not become restricted distally during gas bladder outgrowth. However, Bmp16 activity in the mesenchyme surrounding the gas bladder may contribute to the overall expansion of the organ. Protein structure is conserved between Bmp16, Bmp4, and Bmp2 and all three significantly activate the bmp-signaling pathway (Marques et al., 2016) suggesting Bmp16 may be regulating gas bladder outgrowth similarly to how Bmp4 regulates lung outgrowth. However, without a bichir genome, we do not know whether and where Bmp16 is expressed during bichir lung development. If Bmp16 is expressed in the dorsal foregut during lung development in bichir, then we may conclude that dorsal expression of Bmp16 arose either during the evolution of ray-finned fishes or was the ancestral bony vertebrate pattern, but it did not contribute to the evolution of a dorsal gas bladder. On the other hand, if Bmp16 is not expressed during bichir lung development or is expressed ventrally in the lungs, then Bmp16 expression may have arisen in concert with the evolution of the gas bladder, providing further evidence for its role in regulating gas bladder development. Given what we have found in this study, Bmp4 expression appears to have been lost during the evolution of the gas bladder from ancestral lungs, and Bmp16 expression appears to have been gained in gas bladder development at least for the Actinopteri. Whether Bmp16 is involved in lung development of bichir, representing the sister group to Actinopteri, remains an intriguing question.

5 |. CONCLUSION

Of the genes investigated, Nkx2.1 and Sox2 show conserved spatial and temporal expression patterns between taxa that develop lungs, including bichirs, the only ray-finned fish lineage that has lungs. Based on these shared gene expression patterns in the lungs of bichir and tetrapods, we can infer that Nkx2.1 was likely expressed in the ventral foregut and lung endoderm while Sox2 was likely expressed in the dorsal foregut endoderm during lung development in the common ancestor of bony vertebrates (Figure 9).

Interestingly, during the evolutionary transition from lungs to a gas bladder along the ray-finned fish lineage, Bmp4 expression appears to have been lost and Bmp16 expression appears to have been gained in gas bladder development. Alternatively, it is possible that Bmp16 was lost during the evolution of mammalian lungs. Further study of the patterns of Bmp16 expression in a variety of taxa could distinguish between these possibilities. The dorsal expression of Bmp16 during gas bladder development, inverted compared to Bmp4 expression during lung development, suggests that Bmp16 may have been involved in the shift from ventral to dorsal budding. While the reproductive biology of bowfin makes functional experiments extremely difficult, we hypothesize that CRISPR–Cas9 knockout experiments in zebrafish will reveal important roles of Bmp16 in gas bladder development.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express our appreciation to Dr. Ian Welsh and Dr. Aravind Sivakumar for experimental advice and to all of the Kurpios lab members for valuable feedback throughout the project. Ken Zeedyk generously provided bichir eggs and breeding adults. Thanks also to Dr. Joe Fetcho and Nikki McGuire for supplying zebrafish embryos. Francis Feng graciously allowed us to use his boat ramp for access to bowfin spawning grounds in Oneida Lake. The authors are grateful to Dr. Ingo Braasch and Dr. Andrew Thompson for early access to the bowfin genome. Dr. Jake Berv helped with reconstructing the Bmp gene tree. Dr. Ezra Lencer reviewed an early version of this manuscript. Emily C. Funk was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (2013170607) and a Cornell Presidential Life Sciences Fellowship. Funding for this project was provided by Sigma Xi Cornell Chapter, the Cornell Center for Vertebrate Genomics Scholar’s Program, Dextra Undergraduate Research Endowment Fund, McCune Lab funds, and Cornell EEB Departmental Funds.

Funding information

Cornell EEB Departmental Funds; Graduate Research Fellowship Program, National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: 2013170607; Cornell Presidential Life Sciences Fellowship; Dextra Undergraduate Research Endowment Fund, Cornell; McCune Lab Funds; Cornell Center for Vertebrate Genomics Scholar’s Program; Sigma Xi Cornell Chapter

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Alexander RM (1966). Physical aspects of swimbladder function. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 41, 141–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard WW (1986). Morphogenetic movements and a provisional fate map of development in the holostean fish Amia calva. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 238, 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bani-Yaghoub M, Tremblay RG, Lei JX, Zhang D, Zurakowski B, Sandhu JK, … Sikorska M (2006). Role of Sox2 in the development of the mouse neocortex. Developmental Biology, 295, 52–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci S, Henderson R, Winnier G, Oikawa T, & Hogan BL (1996). Evidence from normal expression and targeted misexpression that bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp-4) plays a role in mouse embryonic lung morphogenesis. Development, 122, 1693–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray AA, Potts WTW, Milner AR, Chaloner WG, & Lawson JD (1985). The evolution of the terrestrial vertebrates: Environmental and physiological considerations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 309, 289–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budgett JS (1902). On the structure of the larval Polypterus. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 16, 315–346. [Google Scholar]

- Cass AN, Servetnick MD, & McCune AR (2013). Expression of a lung developmental cassette in the adult and developing zebrafish swimbladder. Evolution & Development, 15, 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, & Minh BQ (2016). Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Systematic Biology, 65, 997–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack JA (2007). Devonian climate change, breathing, and the origin of the tetrapod stem group. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 47, 510–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels CB, Orgeig S, Sullivan LC, Ling N, Bennett MB, Schurch S, … Brauner CJ (2004). The origin and evolution of the surfactant system in fish: Insights into the evolution of lungs and swim bladders. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 77, 732–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C (1859). On the origins of species by means of natural selection (p. 247). London, UK: Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Dean B (1895). Fishes, living and fossil: An outline of their forms and probably relationships. Dehli, India: Narendra Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Domyan ET, Ferretti E, Throckmorton K, Mishina Y, Nicolis SK, & Sun X (2011). Signaling through BMP receptors promotes respiratory identity in the foregut via repression of Sox2. Development, 138, 971–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner N, Begemann G, Renz AJ, Meyer A, & Kuraku S (2009). The origin of bmp16, a novel Bmp2/4relative, retained in teleost fish genomes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 9, 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner N, Motone F, Meyer A, & Kuraku S (2019). Asymmetric paralog evolution between the “cryptic” gene Bmp16 and its well-studied sister genes Bmp2 and Bmp4. Scientific Reports, 9, 3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JL, Robertson GN, McGee CAS, Smith FM, & Croll RP (2006). Structure and autonomic innervation of the swim bladder in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of Comparative Neurology, 495, 587–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk E, Lencer E, & McCune A (2020). Dorsoventral inversion of the air-filled organ (lungs, gas bladder) in vertebrates: RNAsequencing of laser capture microdissected embryonic tissue. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B. https://doi-org.proxy.library.cornell.edu/10.1002/jez.b.22998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontan C, de Munck A, Vermeij M, Grosveld F, Tibboel D, & Rottier R (2008). Sox2 is important for two crucial processes in lung development: Branching morphogenesis and epithelial cell differentiation. Developmental Biology, 317, 296–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González A, López JM, & Marín O (2002). Expression pattern of the homeobox protein NKX2-1 in the developing Xenopus forebrain. Gene Expression Patterns, 1, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich ES (1958). Studies on the structure and development of vertebrates. New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JB (1997). Air-breathing fishes: Evolution, diversity, and adaptation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grigg GC (1965). Studies on the Queensland lungfish, Neoceratodus forsteri (Krefft). Australian Journal of Zoology, 13, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Grom K (2015). Comparative anatomical study of swimbladder in different species of fish. Scientific Works. Series C. Veterinary Medicine 61, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Helfman G, Collette BB, Facey DE, & Bowen BW (2009). The diversity of fishes: Biology, evolution, and ecology (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Herriges M, & Morrisey EE (2014). Lung development: Orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development, 141, 502–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines EA, & Sun X (2014). Tissue crosstalk in lung development. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 115, 1469–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, & Vinh LS (2018). UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes LC, Ortí G, Huang Y, Sun Y, Baldwin CC, Thompson AW, … Shi Q (2018). Comprehensive phylogeny of ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) based on transcriptomic and genomic data. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 6249–6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Rex M, Scotting PJ, & Yasugi S (1998). Region-specific expression of chicken Sox2 in the developing gut and lung epithelium: Regulation by epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Developmental Dynamics, 213, 464–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, & Jermiin LS (2017). ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods, 14, 587–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardong KV (2015). The respiratory system, Vertebrates: Comparative anatomy, function, evolution (pp. 413–450). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, & Yamada KD (2019). MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 20, 1160–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Jiang M, Huang H, Zhang Y, Tjota N, Gao X, … Que J (2019). Isl1 regulation of Nkx2.1 in the early foregut epithelium is required for trachea-esophageal separation and lung lobation. Developmental Cell, 51, 675–683.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro D, Price M, de Felice M, & Lauro RD (1991). The transcription factor TTF-1 is expressed at the onset of thyroid and lung morphogenesis and in restricted regions of the foetal brain. Development, 113, 1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gordon J, Manley NR, Litingtung Y, & Chiang C (2008). Bmp4 is required for tracheal formation: A novel mouse model for tracheal agenesis. Developmental Biology, 322, 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem KF (1988). Form and function of lungs: The evolution of air breathing mechanisms. American Zoologist, 28, 739–759. [Google Scholar]

- Liem KF (1989). Respiratory gas bladders in teleosts: Functional conservatism and morphological diversity. American Zoologist, 29, 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Longo S, Riccio M, & McCune AR (2013). Homology of lungs and gas bladders: Insights from arterial vasculature. Journal of Morphology, 274, 687–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani TJ, Reed JJ, & Shapiro SD (2002). Expression profiling of the developing mouse lung. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 26, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques CL, Fernández I, Viegas MN, Cox CJ, Martel P, Rosa J, … Laizé V (2016). Comparative analysis of zebrafish bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4 and 16: Molecular and evolutionary perspectives. Cellular and Molecular Life Science, 73, 841–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall NB (1971). Explorations in the life of fishes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marty GD, Hinton DE, & Summerfelt RC (1995). Histopathology of swimbladder noninflation in walleye (Stizostedion vitreum) larvae: Role of development and inflammation. Aquaculture, 138, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Minoo P, Su G, Drum H, Bringas P, & Kimura S (1999). Defects in tracheoesophageal and lung morphogenesis in Nkx2.1(−/−) mouse embryos. Developmental Biology, 209, 60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey EE, & Hogan B (2010). Preparing for the first breath: Genetic and cellular mechanisms in lung development. Developmental Cell, 18, 8–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near TJ, Eytan RI, Dornburg A, Kuhn KL, Moore JA, Davis MP, … Smith WL (2012). Resolution of ray-finned fish phylogeny and timing of diversification. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 13698–13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JS, Grande TC, & Wilson MVH (2016). Fishes of the world. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz DM, & Yin Y (2012). Signaling networks regulating development of the lower respiratory tract. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 4, a008318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pough FH, Heiser JB, & McFarland WN (1996). Vertebrate life. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Que J, Choi M, Ziel JW, Klingensmith J, & Hogan BLM (2006). Morphogenesis of the trachea and esophagus: Current players and new roles for noggin and Bmps. Differentiation, 74, 422–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que J, Okubo T, Goldenring JR, Nam K-T, Kurotani R, Morrisey EE, … Hogan BLM (2007). Multiple dose-dependent roles for Sox2 in the patterning and differentiation of anterior foregut endoderm. Development, 134, 2521–2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin SA, Thi Tran H, Wlizla M, Mancini P, Shifley ET, Bloor SD, … Zorn AM (2015). A molecular atlas of Xenopus respiratory system development. Developmental Dynamics, 244, 69–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AN, & Bass AH (2009). Novel vocal repertoire and paired swimbladders of the three-spined toadfish, Batrachomoeus trispinosus: Insights into the diversity of the Batrachoididae. Journal of Experimental Biology, 212, 1377–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer AS, & Parsons TS (1970). Vertebrate body. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DE, Forey PL, Gardiner BG, & Patterson C (1981). Lungfishes, tetrapods, paleontology, and plesiomorphy. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 167, 159–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sagemehl M (1885). Beitrage zur vergleichenden anatomie der fische III. Das cranium der characiniden nebst allgemeinen bermerkungen uber die mit einen Weber’s schen apparat versehenen physostomen familien. Gegenbaurs Morphologisches Jahrbuch, 10, 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Steen JB (1970). The swim bladder as a hydrostatic organ. In Hoar WS & Randall DJ (Eds.), Fish physiology (pp. 413–443). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi N, Kobayashi R, Yano T, Noda M, Fujimura K, Okada N, & Okabe M (2016). Molecular developmental mechanism in polypterid fish provides insight into the origin of vertebrate lungs. Scientific Reports, 6, 30580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen L-T, von Haeseler A, & Minh BQ (2016). W-IQ-TREE: A fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, W232–W235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videler JJ (1993). Fish swimming. London: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach V (1998). The pulmonary system: The lungs of snakes. In Gans C, & Parsons TS (Eds.), Biology of the reptilia: Morphology G: Visceral organs (pp. 93–295). Ithaca, NY: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles; ). [Google Scholar]

- Weaver M, Dunn NR, & Hogan BL (2000). Bmp4 and Fgf10 play opposing roles during lung bud morphogenesis. Development, 127, 2695–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh IC, Thomsen M, Gludish DW, Alfonso-Parra C, Bai Y, Martin JF, & Kurpios NA (2013). Integration of left-right Pitx2 transcription and Wnt signaling drives asymmetric gut morphogenesis via Daam2. Developmental Cell, 26, 629–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder BG (1877). Gar-pikes, old and young. Popular Science Monthly, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg JB, Copeland DE, Haedrich FRL, & Child JS (1980). The swimbladder of deep-sea fish: The swimbladder wall is a lipid-rich barrier to oxygen diffusion. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 60, 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Miletich I, Kim B-M, Sharpe PT, & Shivdasani RA (2011). Barx1-mediated inhibition of Wnt signaling in the mouse thoracic foregut controls tracheo-esophageal septation and epithelial differentiation. PLoS One, 6, e22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer C, & Emlen DJ (2013). The tree of life, Evolution: Making sense of life (p. 99). Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Company Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.