Abstract

Coronavirus presenting an unforeseeable chain of events has exaggerated misery for students in India as they attracted the most detrimental experiences associated with lockdown restrictions leading to a shutdown of colleges as a preventive measure. The research endeavors to furnish a review of the overall hardships and psychological state of mind of college students and improvement in the implementation of policy decisions. Researchers conceptualize the newly discovered phenomenon by adopting grounded theory. Data from 256 newspaper articles, online articles and magazines have been gathered and converted into 256 separate files. To broaden the justification of research, social media analysis employing tweets, Facebook posts and Whatsapp messages are considered adding to the contributory prospects of the study. Compiled data is then refined through data mining technique. Triangulation approach amalgamating content analysis and thematic analysis has been deployed, thereby exploring the qualitative aspect of data gathering. Reviews from 31 students through telephonic conversation and 8 academic experts extended more accuracy to the research process. Findings administered academic disruptions with career concern, emotional suffering, financial concern, online learning, overseas injustice and psychological effects as the final themes representing various concerns experienced by college students. Hence, this work concludes with some constructive suggestions to deteriorate the amplified concerns.

Students are a source of strength and future pillars for a country contributing to nation‐building. Being vital organs of society, they demand utmost attention and empathy in their growing years to capitalize on available opportunities. Contrasting with the notion of prevalent hardships, the current scenario has also entrusted privilege to innovate and enhance the betterment of self as well as the welfare of society. Individuals proceeding toward the fulfillment of a particular goal with intrinsic motivation, acting as a catalyst, are more likely to get encouraged by the upcoming challenges (Cheng, 2018). However, coronavirus presenting an unforeseeable chain of events has exaggerated misery for students and may demotivate them leading to low positive futuristic growth.

Students involved in higher education are career‐oriented and more likely to get shattered by the nation‐wide imposed lockdown in India initiating from March 24, 2020 with their aims of touching the sky obstructed with the intrusion of Coronavirus. They are at a comparatively sensitive stage where decisions at present will impact their future. Students may develop post‐traumatic stress disorder accompanied by psychiatric issues such as anxiety and depression adding strain to the already burdened minds of this generation (Bolton et al., 2000; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2013). Outcomes of trauma is a secondary perspective but the emotional ordeal becomes first to hit their sensitive minds (Pfefferbaum et al., 2019). Hence, they tend to bear upon mentally during such health emergencies (Franco et al., 2004; Kendler et al., 1999). This notion justifies their concerns to be urgently addressed and overshadows the optimistic side of the situation.

Coronavirus pandemic has stipulated the mankind to realize the ardent need to divert their attention toward deteriorating mental well‐ being of the citizens (Wang et al., 2020). Psychosocial concerns always accompany an epidemic turning into disastrous turmoil even for the unaffected population (Park & Lee, 2016). Students, being a vulnerable group of the society attracted the most detrimental experiences as it has been an unpredictable scenario for them adversely affecting the ongoing educational session. They are introduced to the online mode providing an altogether different approach guiding various teaching‐learning platforms (University Grants Commission, 2020). Moreover, in the present scenario, imposing agony of separation from their friends and families may provide a negative outlook to their future (Rudolph et al., 2008) while risk factors surfacing as they progress toward development may lead to high levels of susceptibility (Jensen Arnett, 2010; Wright et al., 2012).

The emanation of coronavirus provides the researchers with the opportunity to identify the patterns underlying behind the changes taken place and administering the possible effects observed after their implementation. Hence, researchers in the present study try to gather shreds of evidence of the prevailing situation by referring to the relevant pieces of existing literature. However, after much effort, only a handful of studies are identified as justifiable to the context of current research. Table 1 provides an overview of the studies identified crucial to base the structure of present research.

TABLE 1.

Glimpse of relevant work from existing literature

| Author | Aim | Geographical region in focus |

|---|---|---|

| Bao et al., 2020 | To describe the importance of mental health in COVID‐19 scenario | China |

| Brooks et al., 2020 | To review the psychological impact of quarantine | UK |

| Cao et al., 2020 | To analyze the mental situation of college students in China and evaluating basis for psychological intervention along with levels of anxiety. | China |

| Al‐Rabiaah et al., 2020 | To examine the stress associated with impact of MERS‐CoV epidemic on medical students | Saudi Arabia |

| Wang et al., 2020 | To determine the existence of psychological symptoms in the population of China and elaborates the risk and protective factors associated with the psychiatric well‐ being during the corona virus outbreak. | China |

| Blakey et al., 2015 | to examine psychological predictors of anxiety during Ebola threat | United States |

| Goodwin et al., 2009 | To assess the initial behavioral and psychological responses for H1N1 “Swine flu” | Europe and Malaysia |

| Leung et al., 2003 | To review the psychological responses of population to SARS outbreak | Hong Kong |

Since the origin of COVID‐19 is a new medical phenomenon identified only a few months back, there is a paucity of conspicuous researches especially in context of the Indian scenario. Some studies have been conducted justifying clinical characteristics of Coronavirus while some described the prevalent scenario specific to the country‐context (Remuzzi & Remuzzi, 2020; Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020; Xu et al., 2020). Moreover, the concerns of college students have not been addressed except a few (Cao et al., 2020). Some studies reported the psychological concerns of the respective population (Bao et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020) while a description of pre and post predictors of psychological distress considering scenario before and after remaining in quarantine are also ascertained (Brooks et al., 2020). In order to get familiarized with the psychological conduct of a population dealing with concerns when a devastating tragedy overtakes the world, earlier studies focusing on epidemics such as Ebola virus, H1N1 “Swine flu,” SARS and MERS‐Cov are considered (Al‐Rabiaah et al., 2020; Blakey et al., 2015; Goodwin et al., 2009; Leung et al., 2003).

DEVELOPMENT OF THE THEORY

Due to unavailability of literature on the present crisis, it is pivotal to put forward with the development of a theory. The theory is established based on the experts’ views, students’ interviews, secondary data literature including newspaper articles, Internet articles, tweets, and other relevant messages are taken into consideration. These views are presented as sources defining hardships faced by students. Earlier theories such as “Stressor‐strain theory” emphasized on the negative impact, a disclosure to stress elements can impose on health directing toward psychological and behavioral sufferings (Fox et al., 2001; Spector, 1998). There are studies highlighting stressors focusing on academic, emotional and financial crunch describing constraints in a normal situation (Denovan & Macaskill, 2012; Hurst et al., 2013; Robotham, 2008). Hence, a dire need arises to formulate a conceptual structure highlighting the coronavirus scenario, which is an exceptional and unanticipated phenomenon.

The purpose of this research highlighting the concerns of college students amidst COVID‐19 scenario displays a fresh concept. Scanty research studies with no specific theory in Indian context persuaded the researchers to conceptualize this phenomenon and to provide a structure for future research. Hence, the research design propagates the adoption of grounded theory following the inductive approach to fill the gap in the existing literature. Highlighting of the theory is that students are feeling more concerns than prospects and this scenario is creating an atmosphere of depression and struggle with psychological pressure for their career and life.

Hence, it is pertinent to identify hardships in a country like India where gross enrollment ratio was reported as 26.3% with around 37.4 million students in higher education during 2018–2019 (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2020). Considering the situation in context and the relevant literature, researchers after having rationalized thoughts decide upon the following objectives:

To identify and review the concerns of college students in India and Indian students studying abroad amidst the present scenario incorporating COVID‐ 19 outcomes.

To interpret and have a closer view of the mental well‐being of college students so that future online strategy and other relevant points must be taken into consideration.

METHOD AND MATERIALS

Study design

The researchers have adopted exploratory research design by analyzing qualitative data in this study as it has proved to generate impressive results in psychological research (Churchman et al., 2019, Cunningham et al., 2016; Raufelder et al., 2016; Hebert & Popadiuk, 2008; Shalka, 2019). Qualitative techniques using vigilant observations and robust analysis of a phenomenally crucial occurrence allow for powerful theory development, a requisite for the current study. Triangulation of methodologies targeted at introducing a mix of techniques tends to improve the validity and reliability of qualitative analysis. Hence, an amalgamation of content and thematic analysis is employed, popularly used to target qualitative approach based studies (Kracker and Pollio, 2003; Morris, 1994; Tate et al., 2010; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Reviews from 39 respondents including 8 educational experts associated as faculties in reputed colleges with more than 10 years of experience and 31 students in higher education have contributed to extending reliability to this study.

Procedure

The present research has considered 256 articles after going through 510 articles published in newspapers, magazines, and online websites. Instances from articles with the mention of Indian students pursuing higher education from abroad and those involved in academic session in the home country itself have been aggregated and converted into 256 separate files. However, inputs from a social platform such as Twitter, Facebook, Whatsapp messages, and blogs are gathered for going into depth and adding to the contributory prospects of the study (Ciasullo et al., 2018; Troisi et al., 2018).

This paper employed content analysis as it has emerged as an effectual technique useful in determining conceptual text in the form of published data such as case study, news articles, and research articles (Gold et al., 2009). It can accommodate for an effective abbreviation of large data into a smaller version of the text (Shuyler & Knight, 2003).

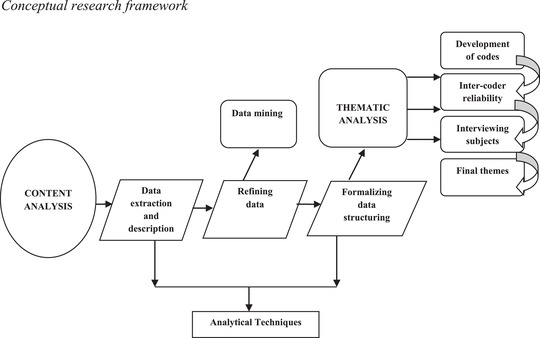

As visible from figure 1, after gathering the relevant data, the text is filtered by practising data mining technique of “keyword extraction.” Providing the refined data with a formalized outlook and connotation, thematic analysis incorporating inductive approach has been employed by the researchers to provide a clearer view of the grouping patterns emanating from the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). It can graciously unpack a rich body of descriptive media text such as articles and social media posts (Walters, 2016). Hence, it is considered as an unobtrusive method of analysis aligning with present research.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual research framework

Note. This diagram is formed in the form of flowchart to demonstrate the step‐by‐step prodecure being followed to strengthen the structure of the research.

Researchers after repetitive readings of the refined text decided upon the codes followed by testing the intercode reliability. Resolving the disagreements between coders, codes are being grouped into prospective themes according to the similarities possessed by them. After considering the views of college students, the final themes are displayed and reported. Previous studies (Frith & Gleeson, 2004; Pettigrew et al., 2015; Raufelder et al., 2016; Walters, 2016) have also found this approach of thematic analysis useful in deciding upon the themes and analyzing data.

DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

All the data gathered has gone through a vigorous refining process and “Data Mining” is effectively deployed for compiling views incorporating maximum importance displaying a meaningful portrayal based on the screening of key words extracted from the data (Ciasullo et al., 2018). For this purpose, the words that constitute the comments have been filtered.

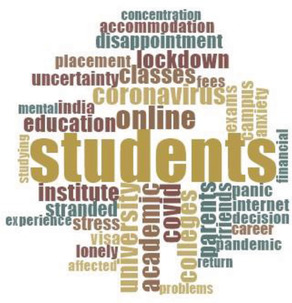

The word count table 2 displaying 42 words frequently used in the data provides the basis for development of their visual representation (see figure 2). For this purpose a word cloud is created through NVIVO 12 plus, identified as an effective tool to demonstrate qualitative data providing deeper insights of the hidden implications (QRS International).

TABLE 2.

Word count table depicting words with maximum weightage

| Word | Length | Count | Weighted percentage (%) | Word | Length | Count | Weighted percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students | 8 | 358 | 10.53 | Anxiety | 7 | 57 | 1.67 |

| University | 10 | 182 | 5.35 | Lonely | 6 | 59 | 1.73 |

| Lockdown | 8 | 161 | 4.74 | Disappointment | 14 | 47 | 1.38 |

| Online | 6 | 156 | 4.59 | Fees | 4 | 45 | 1.32 |

| Classes | 7 | 147 | 4.32 | Accommodation | 13 | 44 | 1.29 |

| COVID | 5 | 147 | 4.32 | Internet | 8 | 43 | 1.26 |

| Colleges | 8 | 145 | 4.26 | Friends | 7 | 42 | 1.23 |

| Coronavirus | 11 | 135 | 3.97 | Stranded | 8 | 40 | 1.17 |

| Parents | 7 | 135 | 3.97 | Stress | 6 | 38 | 1.11 |

| Academic | 8 | 134 | 3.94 | Uncertainty | 11 | 36 | 0.05 |

| Education | 9 | 114 | 3.35 | Decision | 8 | 34 | 1.00 |

| Institute | 9 | 109 | 3.20 | Financial | 9 | 34 | 1.00 |

| Campus | 6 | 108 | 3.17 | Loan | 4 | 32 | 0.94 |

| Placement | 6 | 90 | 2.64 | Travel | 6 | 31 | 0.91 |

| Pandemic | 8 | 88 | 2.58 | Cancelled | 9 | 31 | 0.91 |

| India | 5 | 75 | 2.20 | Connectivity | 12 | 30 | 0.88 |

| Visa | 4 | 75 | 2.20 | Distancing | 10 | 29 | 0.85 |

| Exams | 5 | 73 | 2.14 | Infection | 9 | 27 | 0.79 |

| Career | 6 | 68 | 2.00 | Vacate | 6 | 26 | 0.76 |

| Panic | 5 | 68 | 2.00 | Homes | 5 | 20 | 0.58 |

Note. Complied by the researchers to present the frequency of words depicting weightage with the help of analysis produced through NVIVO 12 plus.

FIGURE 2.

Word cloud [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note. This diagram is created in NVIVO 12 plus software and each word in the figure is depicting the amount of repetitions. The largest word is the most recurring one.

“Students” displaying the largest size, represent the word with most repetitions while many articles and tweets are focused at “university”‐level difficulties and their effect on student's psychological and physical state . The words “pandemic,” “COVID,” and “Coronavirus” are used commonly in articles since the whole research is subject to the impact this erratic situation has created. Inclusion of other words is supporting the structure of thematic formations.

Development of codes

Initially, working through the data again and again in order to give a meaning to the whole pool of thoughts and understand the context of every sentence, which is necessary for the development of more appropriate data‐based themes (Nowell et al., 2017). All the initial ideas were brainstormed and noted down. Coding is recognized as a crucial part of this analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Hence, codes are identified by examining the persistently repetitive words and depicting the idea they represent thereby searching for synonymity along with differences in the text (Attride‐Stirling, 2001).

Intercoder reliability

An intercoder reliability test was conducted to ensure the accuracy of the coding scheme to the maximum extent with the help of Cohen's Kappa (k) as a measure to judge the level of agreement between the coders. Intercoder reliability as described in some portions of literature is corroborated when at least two coders are considered making the coding activity a dual repetitive process (Duriau et al., 2007).

In the context of the present research, both the authors characterized as coders proceeded with raw data to identify coding categories separately without any prior discussion. A total of 60 codes were developed as a part of this process. Further reviews from the academic experts were solicited to eliminate less relevant codes and merge the synonymous ones, a crucial step in defining reliability to a greater extent (Barkin et al., 1999; Jehn & Doucet, 1997). After this refinement process, 38 codes were obtained as the input to be scrutinized for testing intercoder reliability. Codes were analyzed separately to justify the condition of independent judgment for determining the value of Cohen's Kappa (Banerjee et al., 1999; Cohen, 1960; Jo et al., 2011; Lombard et al., 2002). Responses derived from the coders are investigated using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.

The results displayed in the table 3 depicts the value of Cohen's Kappa as .721 at 5% level of significance (p < .05), which illustrates a substantial amount of agreement between the two coders as a value higher than 0.70 has been considered reliable enough (Lombard et al., 2002). Hence, to establish maximum reliability the researchers discussed upon the codes and themes again and only after mutual consent the thematic process has been carried out. Finally, the codes that aroused disagreement and mutual denial between the coders were eliminated thereafter and 32 codes were incorporated in themes.

TABLE 3.

Results of intercoder reliability test

| Value | Asymp. std. errora | Approx. T b | Approx. sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure of agreement Kappa | .721 | 0.187 | 4.442 | .000 |

| No. of valid cases | 38 |

aUsing the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesi hypothesis.

bNot assuming the null hypothesis.

Final themes

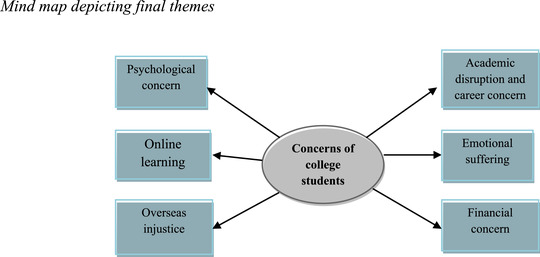

All the determined codes are categorized and grouped into suitable themes based on ascertained similarity (Braun & Clarke, 2006; King, 2018; Walters, 2016). Themes and associated codes are finalized after refining the coding structure and defined more appropriately. To avoid the hypothetical and misleading themes, college students contacted described their psychological state of mind and accuracy of the identified themes. Hence, thematic analysis of the extracted data divulged about the 6 finalized themes with Theme 1, 2, and 3 on the left and Theme 4, 5, and 6 on the right, illustrated through mind map in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Mind map depicting final themes [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note. For better understanding, the components of this figure can be read from left to right.

Theme 1: Psychological concern

This theme describes the abrupt distortions created affecting the mental health of college students. The theme is clearly presented in table 4. Rigid lockdown restrictions leading to shutdown of universities and colleges have imposed certain mental pressure and sudden changes affecting mental health of students (Cao et al., 2020). College students are more prone to develop psychological disorders and many researches have presented its demonstration (Guloglu, 2016). Students have even reported views describing suicidal thoughts. Reaction to various unfortunate events differs and so the emotional burden the youth face (Pfefferbaum et al., 2019). Students already suffering from health disorders reported an aggravated level of anxiety and depression. Forced isolation has aroused a feeling of lacked togetherness among people leading them to feel like a trapped soul.

TABLE 4.

Codes depicting “Psychological concern”

| Codes | Definition | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety created by sudden isolation | Sudden announcement of lockdown creating pressure on minds | 72 | 75 |

| Amplified level of depression | Increasing depression due to uncertainties created by coronavirus | 89 | 93 |

| Panic attacks | Worsening of prevailing mental health condition leading to panic attack | 36 | 38 |

| Insecurity regarding self‐safety | Fear of getting infected by deadly coronavirus | 81 | 82 |

| Stress associated with changes in lifestyle | Chaos and hype surrounding the outbreak with complete change in routine | 71 | 74 |

| Possibility of suicidal attempts | Already facing mental disturbances enlarging the scope of suicidal attempts | 23 | 25 |

| Feeling trapped inside the house | Suffocating in house being isolated | 58 | 58 |

Note. Based on the output of codes demonstrating “Psychological concern” in NVIVO 12 plus.

Theme 2: Online learning

The 'online learning' theme is well‐presented in table 5. Due to lockdown restrictions classroom teaching has been shifted to online mode. Online learning platforms have increased the reach of education where opportunities will not be restricted (Sun et al., 2018). Embracing technology is a crucial step for promoting effective online teaching (Delen et al., 2014; Mirzajani et al., 2016; Tay et al., 2012). But in the absence of connectivity or low Internet speed with regular classes going on, they perceive it as a forceful implied obligation for them. Students’ belonging to the technical departments depicted resistance owing to the inability of online learning in practically demonstrating concepts. Online courses are not able to fulfill the interaction requirements of students and still lack personalized touch, continuous support and feedback that deteriorate learning (Sun et al., 2018).

TABLE 5.

Codes depicting “Online learning”

| Codes | Definition | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity issue and low Internet speed | Network problems restricting online learning | 68 | 71 |

| Dissatisfaction with regard to online internal assessment | Internal assessment being conducted online creating worries regarding new pattern and mode | 41 | 41 |

| Forced online lectures | Instances showing least interested students with replacement of classroom learning | 80 | 82 |

| Lack of interaction during online classes | Difficulties regarding group discussions and other interactive part | 88 | 89 |

| No scope of practical demonstrations | Inability to get demonstration and practice the concepts physically | 72 | 78 |

| Unavailability of required infrastructure | Lack of resources such as Internet connection and required device like laptop | 71 | 76 |

Note. Based on the output of codes demonstrating “Online learning” in NVIVO 12 plus.

Theme 3: Overseas injustice

This theme incorporates only the college students who are pursuing their degree from a foreign university as represented in table 6. Concerns vary across the international border of India leaving the students to face misery. As per the descriptions provided by the data, universities demanded students to vacate the assigned accommodation and even declined the request of partial refund for the unused facilities. Students were facing issues regarding visa technicalities and those granted visa were uncertain about the continuation of next session. Increasing level of strictness and rigidity leading to shut down of international operating flights created chaos among them. Those who seemed fortunate enough to reach India mandated to attend lectures at odd timings displaying the time difference between nations.

TABLE 6.

Codes depicting “Overseas injustice”

| Codes | Definition | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Declined fees refund request | Request declined as against refund of unused rooms, board fees and other unutilized facilities by universities | 70 | 72 |

| Fear of being kicked out as the session begins | Fearing to be dismissed if not able to return on time or deposit fees | 58 | 60 |

| Forced to vacate campus accommodation | Forced to leave the campus due to outbreak | 98 | 103 |

| Online lectures at night | Unusual timings of lecture due to time difference in India and Abroad after returning | 35 | 39 |

| Panic mode due to travel ban | Every government restricting international travel | 78 | 81 |

| Visa issues | Difficulties regarding visa and fear of not being able to return Abroad | 60 | 61 |

Note. Based on the output of codes demonstrating “Overseas injustice” in NVIVO 12 plus.

Theme 4: Academic disruptions and career concern

This significant theme is described with the help of table 7. Most of the articles reflect that students are doubtful about the idea of recruitment and networking that have been scraped or streamed online. Those who have bagged the jobs are in dilemma about the fact that whether they will be called or dropped down. But there is a different set of issues awaiting the students yet to cover more years for completion of degree course showing uncertainty about the beginning and pace of the next session. On the other hand, all the college students are worried about the fate of their final exam conduction and result as cognitive aspects of learner's engagement in an educational institution like grade point average prove to be an aspect to determine academic success (Adams et al., 2018). Unpredictability regarding the progress of academic session may have a negative impact on the psychological well‐being of students (Wang et al., 2020). This disturbance and diversion owing to the uncertainty regarding the status of exams compelled them to be inactive and less concentrated toward studies.

TABLE 7.

Codes depicting “Academic disruption and career concern”

| Codes | Definition | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internships and placement interviews interrupted | Reference to the disruptions caused in practical knowledge acquired through field work along with placement interviews | 86 | 93 |

| Uncertainty revolving around future job prospects | Possibility of less job opportunities due to economic slowdown | 72 | 75 |

| Concern regarding next academic session | Pace of next session and delay in its commencement causing concern | 57 | 64 |

| Uncertainty over final exam and results | Dilemma whether exams will take place or not and the corresponding result tension | 96 | 101 |

| Losing concentration and focus on studies | Disturbances in mind declining focus in studies | 57 | 58 |

Note. Based on the output of codes demonstrating “Academic disruption and career concern” in NVIVO 12 plus.

Theme 5: Emotional suffering

This theme displayed in table 8 is associated with struggling emotions of students associated with family and friends. Students stranded in different areas of their country and Abroad displayed immense desperation to get back to their respective homes while some apprehensive about the unintentional possibility of being virus carriers while back home. Those unable to return felt a sense of loneliness lacking support from their loved ones. They also seem disheartened about the fact that they might not get a chance to cherish their graduation ceremony, birthday parties, and other events while losing interaction with the friends following lockdown norms. Social support from family, friends, and teachers may be used as a tool in difficult situations targeted at limiting life stressors.

TABLE 8.

Codes depicting “Emotional suffering”

| Codes | Definition | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desperation to get home | Students away from home desperately wanting to return | 79 | 81 |

| Disappointment over positive events being cancelled | Reactions to events like birthdays' and graduation ceremonies' cancellation | 64 | 66 |

| Fear of being virus carrier while travelling back home | Fearing the chance to get the family members infected | 59 | 59 |

| Loneliness | Feeling lonely being away from family | 49 | 50 |

| Restricted interaction with peer group | Emotions describing limited or no interaction with friends | 75 | 76 |

Note. Based on the output of codes demonstrating “Emotional suffering” in NVIVO 12 plus.

Theme 6: Financial concern

Financial woes are hampering the smooth flow of students’ life. Undoubtedly, university education presents a scenario where commitment and hard work requirements move parallel to huge financial investment involved (Andrews & Wilding, 2004). There are students who have taken loans for educational purpose and are bound to pay regular EMIs for that. Many courses exert heavy demand on finances and hence, sometimes people opt for loans (Agrawal & Chahar, 2007). A mere thought of discontinuation of studies or a possibility of future shift of educational institute owing to the heavy financial distress going on make them numb with fear. Moreover, students stuck at other places are finding it difficult to survive with declining financial ability to satisfy essential needs comprising rent for added stay and food expenses. Summing up the financial constraints, loss in business or underpaid and due salary of their parents are arising great amount of dismay among the students (see table 9).

TABLE 9.

Codes depicting “Financial concern”

| Codes | Definition | Files | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burden of educational loan | Worries regarding payment of education loan and their EMIs | 61 | 63 |

| Influence by parents’ struggling phase | Concerns displaying reduced or no income during lockdown period | 49 | 50 |

| Striving to pay for basic amenities | Describing reduced ability to pay for rent, food and other essentials | 93 | 102 |

Note. Based on the output of codes demonstrating “Financial concern” in NVIVO 12 plus.

Weighted themes

Illustration of themes in Table 10 highlights the relevance of themes according to the weightage and ranks assigned. The chronological order depicting the weighted significance has been used to assign numbers and arrange the themes in the specified order. The most significant theme has been numbered as “Theme 1” and the last one as “Theme 6.” Psychological concern is undoubtedly the foremost challenge for students. Other concerns represent the problems confronted by them posing threat to their health and well‐being.

TABLE 10.

Weighted theme coverage

| Theme | References | Coverage | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological concern | 445 | 16.74% | 1 |

| Online learning | 437 | 13.24% | 2 |

| Overseas injustice | 416 | 12.88% | 3 |

| Academic disruptions and career concern | 391 | 12.07% | 4 |

| Emotional suffering | 332 | 11.89% | 5 |

| Financial concern | 215 | 8.03% | 6 |

Financial concern records considerably less impact as compared to other themes may be due to the fact that students getting education from a distant university faced more financial constraints rather than the ones pursuing degree from their home town itself.

JUSTIFICATION OF THEORY

The current scenario has entrusted both advances and concerns for the college students. But constraints presented by this uncertain event have overshadowed the prospects it offers. Content analysis and thematic analysis supported the qualitative review of the psychological framework of students striving to adapt to the new dynamics emerged. Inclusion of students also justifies the validity of the process to some extent as this approach is termed as idealistic in a situation when the researchers incorporate the subject of the study as respondents (Patton, 1990). This research is also in line with the “Stressor‐strain theory” suggested by Spector (1998) identifying effects on psychological and emotional well‐being. As argued by Hurst et al. (2013) in the qualitative review of students’ stressors; relationships, academic front, transition from school, expectations, assortment, and environment form majors constraints affecting students while another qualitative research examining a vast literature and sources identified similar obstructions in a general situation (Denovan & Macaskill, 2012). The present study has some components of the prior research including emotional suffering, psychological effects, academic and financial concerns but the unique scenario presented by coronavirus has also added overseas injustice and learning difficulty in case of the online version of classes as the major concerns specific to this situation. Thus, after much investigation, the findings authenticate the appropriateness of grounded theory with academic and career concerns, overseas injustice, online approach, financial concerns, emotional suffering and psychological effects emerging as major determinants of students’ misery and state of mind during the baffling scenario. Hence, it is substantiated that “Students are feeling more concerns than prospects and this scenario is creating an atmosphere of depression and struggle with psychological pressure for their career and life.”

LIMITATION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Qualitative research has been valued and appreciated imperatively to generate meaningful results by employing a rigorous and methodological process (Nowell et al., 2017). But owing to the subjective nature of this approach capitalized on the researchers’ knowledge and understanding, it introduces a possible bias on the part of researchers (Attride‐ Sterling, 2001). There can be multiple ways of constructing themes utilizing the same data (Jehn & Doucet, 1997) so it is quite difficult to prove the validity of the conceptual process. Considering confined time limits for extracting and interpreting the data presents a challenge for researchers to decide the depth of study they want to divulge in. Concerning secondary data analysis, the whereabouts of the data are deeply examined making it a tedious and time‐consuming process (Tate et al., 2010).

This study has been conducted in the context of Indian students, thus, a global perspective is concerned only with respect to Indian students studying abroad. Future research may be directed toward inclusion of foreign students studying in or outside India, hence elaborating the global perspective of the study. Absence of considerations toward diploma and certificate courses’ students has restricted this study to only graduates and postgraduates. Their inclusion could have added more precision to the study. Moreover, demonstrating thoughts of school students could identify a different set of struggles specific to this segment.

The chain of events in the present study represents a fast proceeding scenario and the research is structured around it with the major focus on theory building particularly demonstrating the concerns concerning the students restricted to the tough and unpredictable circumstances only. It is difficult to replicate this study in a country less affected by coronavirus where the students might have been experiencing an optimistic attitude. The proposed theory could be structured and provide a basis for the initiation of further research in this area in the context of other countries facing the wrath of coronavirus, enhancing the replicability of the present study.

CONCLUSION

This research work illustrates an in‐depth and systematic research process to be rigorous and valid contemplating the data practicing inductive structure. Since all the judgments express researchers’ perspective describing a particular situation, making the procedure more explicit allows for more clarity (Kolbe & Burnett, 1991; Ryan & Bernard, 2003). The qualitative approach adopted in this study incorporates the views of college students, a community as a whole which is much difficult in case of quantitative analysis. The quantitative study represents a limited amount of respondents trying to represent the population but qualitative analysis is an actual representation of the whole community. Hence, researchers found a qualitative framework more accurate in describing this unexplored phenomenon.

The research is concluded with some useful suggestions where students fearing contraction have developed a frightening attitude may be due to the spread of false rumors surrounding claims and reports. Social media is regarded as an important and effective platform for delivering updated medical and other essential information during outbreaks of infectious diseases (Freberg et al., 2013). Students often prioritize the use of gadgets and assistance through a mobile phone application has proved to be successful in psychiatric education (Zhang et al., 2014). The timeliness of communication intervention delivered by authorities plays an important role in effective implementation. It is suggested that communicating to the public about the actual threat and necessary precautions to be taken prove to be an asset for the health authorities during a public health emergency (Gentili et al., 2020).

University and colleges should organize interactions for students with seniors and peers to ensure positive interaction and develop resilience. Special attention should be given to the arrangement of counselors whenever the need arises. Psychological symptoms should be addressed on time so that they can be prevented from converting into actual disorders such as stress, depression, and suicide. Group programs can be introduced for students dealing with psychological issues (Guloglu, 2016).

Hence, this study tries to divert the attention of society toward the mental health of college students that gets negatively affected given the ambiguous prevalent situation. It has presented a different outlook for readers enhancing more significance for the academicians due to the theory formulation being an addition to the prevalent theories and literature owing to its pandemic‐specific nature that will enhance prospects of future research monitoring public emergencies and unusual situation. Since, students are major components of this modern educative society; a student losing on an entire year of education can be the worst‐case scenario. The research will guide the policymakers to evaluate their concerns and formulate policy decisions to ease their pain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the students who have provided participatory response for the better understanding of the scenario undermining students’ state during the pandemic. In order to preserve their identity, the data gathered through their responses has been keep confidential. The data through responses and study material will not be made available to other researchers and the research was not preregistered.

Biographies

Riya Gupta is associated with J.C. Bose University of Science and Technology, YMCA, Faridabad, India and has proved her excellence through academic performance throughout the university level. Her keen interest in social and psychological issues promises high quality research.

Rachna Agrawal is an associate professor at the department of management studies in J.C. Bose University of Science and Technology, YMCA, Faridabad, India and has a teaching experience of almost 18 years. She has a valuable contribution in the field of social issues and management throughout these years.

Gupta R, Agrawal R. Are the concerns destroying mental health of college students?: A qualitative analysis portraying experiences amidst COVID‐19 ambiguities. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2021;21:621–639. 10.1111/asap.12232

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Riya Gupta, Email: riyagupta767@gmail.com.

Rachna Agrawal, Email: rachna.aggr@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- Adams, B.G. , Wiium, N. & Abubakar, A. (2018) Developmental assets and academic performance of adolescents in Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48 (2), 207–222. 10.1007/s10566-018-9480-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.K. & Chahar, S.S. (2007) Examining role stress among technical students in India. Social Psychology of Education, 10 (1), 77–91. 10.1007/s11218-006-9010-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Rabiaah, A. , Temsah, M. , Al‐Eyadhy, A.A. , Hasan, G.M. , Al‐Zamil, F. , Al‐Subaie, S. , et al. (2020) Middle East respiratory syndrome‐corona virus (MERS‐Cov) associated stress among medical students at a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13 (5), 687–691. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, B. & Wilding, J.M. (2004) The relation of depression and anxiety to life‐stress and achievement in students. British Journal of Psychology, 95 (4), 509–521. 10.1348/0007126042369802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attride‐Stirling, J. (2001) Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1 (3), 385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, M. , Capozzoli, M. , McSweeney, L. & Sinha, D. (1999) Beyond kappa: A review of interrater agreement measures. Canadian Journal of Statistics, 27 (1), 3–23. 10.2307/3315487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y. , Sun, Y. , Meng, S. , Shi, J. & Lu, L. (2020) 2019‐nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. The Lancet, 395 (10224), e37–e38. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30309-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin, S. , Ryan, G. & Gelberg, L. (1999) What pediatricians can do to further youth violence prevention—A qualitative study. Injury Prevention, 5 (1), 53–58. 10.1136/ip.5.1.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakey, S.M. , Reuman, L. , Jacoby, R.J. & Abramowitz, J.S. (2015) Tracing “Fearbola”: Psychological predictors of anxious responding to the threat of Ebola. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39 (6), 816–825. 10.1007/s10608-015-9701-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, D. , O'Ryan, D. , Udwin, O. , Boyle, S. & Yule, W. (2000) The long‐term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: II: General psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41 (4), 513–523. 10.1111/1469-7610.00636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.K. , Webster, R.K. , Smith, L.E. , Woodland, L. , Wessely, S. , Greenberg, N. , et al. (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395 (10227), 912–920. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W. , Fang, Z. , Hou, G. , Han, M. , Xu, X. , Dong, J. , et al. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W. (2018) How intrinsic and extrinsic motivations function among college student samples in both Taiwan and the U.S. Educational Psychology, 39 (4), 430–447. 10.1080/01443410.2018.1510116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churchman, A. , Mansell, W. , Al‐Nufoury, Y. & Tai, S. (2019) A qualitative analysis of young people's experiences of receiving a novel, client‐led, psychological therapy in school. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19 (4), 409–418. 10.1002/capr.12259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciasullo, M.V. , Troisi, O. , Loia, F. & Maione, G. (2018) Carpooling: Travelers’ perceptions from a big data analysis. The TQM Journal, 30 (5), 554–571. 10.1108/tqm-11-2017-0156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20 (1), 37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, C.E. , Mapp, C. , Rimas, H. , Cunningham, L. , Mielko, S. , Vaillancourt, T. , et al. (2016) What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A Thematic analysis of the perspective of students. Psychology of Violence, 6 (4), 596–606. 10.1037/a0039984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delen, E. , Liew, J. & Willson, V. (2014) Effects of interactivity and instructional scaffolding on learning: Self‐regulation in online video‐based environments. Computers & Education, 78, 312–320. 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denovan, A. & Macaskill, A. (2012) An interpretative phenomenological analysis of stress and coping in first year undergraduates. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (6), 1002–1024. 10.1002/berj.3019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne, S. & Ratelle, C.F. (2013) Attachment security to mothers and fathers and the developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms in adolescence: Which parent for which trajectory? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43 (4), 641–654. 10.1007/s10964-013-0029-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duriau, V.J. , Reger, R.K. & Pfarrer, M.D. (2007) A content analysis of the content analysis literature in organization studies: Research themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10 (1), 5–34. 10.1177/1094428106289252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, S. , Spector, P.E. & Miles, D. (2001) Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59 (3), 291–309. 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franko, D.L. , Striegel‐Moore, R.H. , Brown, K.M. , Barton, B.A. , Mcmahon, R.P. , Schreiber, G.B. , et al. (2004) Expanding our understanding of the relationship between negative life events and depressive symptoms in black and white adolescent girls. Psychological Medicine, 34 (7), 1319–1330. 10.1017/s0033291704003186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freberg, K. , Palenchar, M.J. & Veil, S.R. (2013) Managing and sharing H1N1 crisis information using social media bookmarking services. Public Relations Review, 39 (3), 178–184. 10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frith, H. & Gleeson, K. (2004) Clothing and embodiment: Men managing body image and appearance. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 5 (1), 40–48. 10.1037/1524-9220.5.1.40 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili, D. , Bardin, A. , Ros, E. , Piovesan, C. , Ramigni, M. , Dalmanzio, M. , et al. (2020) Impact of communication measures implemented during a school tuberculosis outbreak on risk perception among parents and school staff, Italy, 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (3), 911. 10.3390/ijerph17030911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold, S. , Seuring, S. & Beske, P. (2009) Sustainable supply chain management and inter‐organizational resources: A literature review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,17 (4), 230–245. 10.1002/csr.207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, R. , Haque, S. , Neto, F. & Myers, L.B. (2009) Initial psychological responses to influenza A, H1N1 ("Swine flu"). BMC Infectious Diseases, 9 (1), 166. 10.1186/1471-2334-9-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guloglu, B. (2016) Mediating role of psychiatric symptoms on the relationship between learned resourcefulness and life satisfaction among Turkish university students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69 (2), 95–105. 10.1111/ajpy.12122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, S. & Popadiuk, N. (2008) University students' experiences of nonmarital breakups: A grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 49 (1), 1–14. 10.1353/csd.2008.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, C.S. , Baranik, L.E. & Daniel, F. (2013) College student stressors: A review of the qualitative research. Stress and Health, 29 (4), 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- India Brand Equity Foundation . (2020, April). Education Industry Analysis—Reports . Retrieved from https://www.ibef.org/industry/education-sector-india.aspx. Internet information database

- Jehn, K.A. & Doucet, L. (1997) Developing categories for interview data: Consequences of different coding and analysis strategies in understanding text: Part 2. CAM Journal, 9 (1), 1–7. 10.1177/1525822x970090010101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Arnett, J. (2010) Emerging adulthood(s). In Jensen Arnett J. (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental approaches to psychology (pp. 255–275). United States: Oxford Scholarship Online. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195383430.003.0012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, K. , An, G.J. & Sohn, K. (2011) Qualitative content analysis of suicidal ideation in Korean college students. Collegian, 18 (2), 87–92. 10.1016/j.colegn.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K.S. , Karkowski, L.M. & Prescott, C.A. (1999) Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156 (6), 837–841. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, N. & Brooks, J. (2018) Thematic analysis in organisational research. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: Methods and Challenges. Sage Publishing; (pp. 219–236). 10.4135/9781526430236.n14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, R.H. & Burnett, M.S. (1991) Content‐analysis research: An examination of applications with directives for improving research reliability and objectivity. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (2), 243–250. 10.1086/209256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kracker, J. & Pollio, H.R. (2003) The experience of libraries across time: Thematic analysis of undergraduate recollections of library experiences. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54 (12), 1104–1116. 10.1002/asi.10309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G.M. (2003) The impact of community psychological responses on outbreak control for severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57 (11), 857–863. 10.1136/jech.57.11.857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, M. , Snyder‐Duch, J. & Bracken, C.C. (2002) Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research, 28 (4), 587–604. 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzajani, H. , Mahmud, R. , Fauzi Mohd Ayub, A. & Wong, S.L. (2016) Teachers’ acceptance of ICT and its integration in the classroom. Quality Assurance in Education, 24 (1), 26–40. 10.1108/qae-06-2014-0025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R. (1994) Computerized content analysis in management research: A demonstration of advantages & limitations. Journal of Management, 20 (4), 903–931. 10.1177/014920639402000410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S. , Norris, J.M. , White, D.E. & Moules, N.J. (2017) Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1), 160940691773384. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. & Lee, B.J. (2016) The role of social work for foreign residents in an epidemic: The MERS crisis in the Republic of Korea. Social Work in Public Health, 31 (7), 656–664. 10.1080/19371918.2016.1160352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research methods. United States: SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1990-97369-000 [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, S. , Archer, C. & Harrigan, P. (2015) A thematic analysis of mothers’ motivations for blogging. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20 (5), 1025–1031. 10.1007/s10995-015-1887-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, B. , Nitiéma, P. & Newman, E. (2019) A meta‐analysis of intervention effects on depression and/or anxiety in youth exposed to political violence or natural disasters. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48 (4), 449–477. 10.1007/s10566-019-09494-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- QRS International . Retrieved from https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/about/nvivo

- Raufelder, D. , Nitsche, L. , Breitmeyer, S. , Keßler, S. , Herrmann, E. & Regner, N. (2016) Students’ perception of “good” and “bad” teachers—Results of a qualitative thematic analysis with German adolescents. International Journal of Educational Research, 75, 31–44. 10.1016/j.ijer.2015.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi, A. & Remuzzi, G. (2020) COVID‐19 and Italy: What next? The Lancet, 395 (10231), 1225–1228. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30627-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robotham, D. (2008) Stress among higher education students: Towards a research agenda. Higher Education, 56 (6), 735–746. 10.1007/s10734-008-91371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothan, H.A. & Byrareddy, S.N. (2020) The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) outbreak. Journal of Autoimmunity, 109, 102433. 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K.D. , Flynn, M. & Abaied, J.L. (2008) A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In Abela J. R. Z. & Hankin B. L. (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents (pp. 79–102). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G.W. & Bernard, H.R. (2003) Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15 (1), 85–109. 10.1177/1525822x02239569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalka, T.R. (2019) Saplings in the Hurricane: A grounded theory of college trauma and identity development. The Review of Higher Education, 42 (2), 739–764. 10.1353/rhe.2019.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shuyler, K.S. & Knight, K.M. (2003) What are patients seeking when they turn to the internet? Qualitative content analysis of questions asked by visitors to an orthopaedics web site. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 5 (4), e24. 10.2196/jmir.5.4.e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. (1998) A control theory of the job stress process. In Cooper C. L. (Ed.), Theories of organizational stress (pp. 153–169). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.C. , Yu, S. & Chao, C. (2018) Effects of intelligent feedback on online learners’ engagement and cognitive load: The case of research ethics education. Educational Psychology, 39 (10), 1293–1310. 10.1080/01443410.2018.1527291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tate, W.L. , Ellram, L.M. & Kirchoff, J.F. (2010) Corporate social responsibility reports: A thematic analysis related to supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 46 (1), 19–44. 10.1111/j.1745-493x.2009.03184.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tay, L.Y. , Lim, S.K. , Lim, C.P. & Koh, J.H. (2012) Pedagogical approaches for ICT integration into primary school English and mathematics: A Singapore case study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28 (4), 740–754. 10.14742/ajet.838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi, O. , Grimaldi, M. , Loia, F. & Maione, G. (2018) Big data and sentiment analysis to highlight decision behaviours: A case study for student population. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37 (10–11), 1111–1128. 10.1080/0144929x.2018.1502355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- University Grants Commission (2020) Preventive measures to achieve “Social Distancing”—Permission to Teaching and Non‐Teaching staff to work from home (F.No.1‐14/2020). Ministry of Human Resource Development. https://www.ugc.ac.in/pdfnews/7248697_UGC‐Advisory—Permission‐to‐work‐from‐home‐in‐view‐of‐COVID‐19.pdf

- Vaismoradi, M. , Turunen, H. & Bondas, T. (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15 (3), 398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, T. (2016) Using thematic analysis in tourism research. Tourism Analysis, 21 (1), 107–116. 10.3727/108354216x14537459509017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , Ho, C.S. , et al. (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (5), 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.O. , Masten, A.S. & Narayan, A.J. (2012) Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. , Shi, L. , Wang, Y. , Zhang, J. , Huang, L. , Zhang, C. , et al. (2020) Pathological findings of COVID‐19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8 (4), 420–422. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.W. , Ho, C.S. & Ho, R.C. (2014) Methodology of development and students' perceptions of a psychiatry educational smartphone application. Technology and Health Care, 22 (6), 847–855. 10.3233/thc-140861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]