Although there is risk of re-bleeding from a ruptured AVM, most are not treated in the acute period. Here, the authors acutely treated 23 ruptured AVMs. They achieved complete obliteration in 57%; 3 contained intranidal aneurysms, presumably the cause of the presenting hemorrhage. Of the 43% that were incompletely obliterated, 6 had intranidal aneurysms. During a mean follow-up of 21 months, no repeat hemorrhages occurred. Thus, endovascular treatment in the acute phase cured most ruptured AVMs. All 9 AVM-associated aneurysms that were considered the source of hemorrhage were excluded from the circulation. In patients with AVM-related hemorrhagic stroke, prompt angiographic diagnosis and treatment may improve prognosis by reducing repeat hemorrhage rate.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Patients with ruptured brain AVMs are at considerable risk of repeat hemorrhage, particularly when associated intranidal or flow-related aneurysms are present. There is controversy about the timing of diagnosis and treatment of patients with hemorrhagic stroke. We present our results of endovascular treatment of ruptured AVMs in the acute phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Between January 2008 and March 2011, 23 patients (16 men, 7 women; mean age 42 years) with AVM-related hemorrhagic stroke were treated with endovascular techniques within 10 days of the ictus. There were 10 micro-AVMs (< 1 cm) and 1 single-hole pial fistula. In 9 patients, an intranidal or flow-related aneurysm was the likely cause of hemorrhage.

RESULTS:

Complete obliteration of the AVM with Onyx was achieved in 13 of 23 patients (57%). Eight of the 13 AVMs were micro-AVMs and 3 had an intranidal aneurysm. Partial obliteration of the AVM was achieved in 10 of 23 patients (43%). In 6 of these 10 patients, an intranidal (n = 1) or flow-related aneurysm (n = 5) was obliterated with Onyx or coils. There were no complications of treatment. During a mean follow-up of 21 months in 22 surviving patients, no repeat hemorrhage occurred.

CONCLUSIONS:

Endovascular treatment with Onyx in the acute phase cured most ruptured AVMs. All 9 AVM-associated aneurysms that were considered the source of hemorrhage could be excluded from the circulation. In patients with AVM-related hemorrhagic stroke, prompt angiographic diagnosis and treatment may improve prognosis by reducing repeat hemorrhage rate.

Treatment of brain AVMs remains, to some extent, controversial because of the numerous variables affecting the results and uncertainties about the natural course.1–9 This is true not only for unruptured AVMs but also after a hemorrhagic episode. Patients with an AVM initially presenting with hemorrhagic stroke have a substantially higher risk of subsequent bleeding than those presenting with seizures or other symptoms. The risk is much higher in men than in women.10 Some angioarchitectural features of brain AVMs are associated with hemorrhage, such as the presence of intranidal aneurysms or flow-related aneurysms and venous outflow restriction by stenoses. Specific elimination of these weak spots or reduction of flow through the AVM by endovascular or surgical therapy is thought to decrease the rate of repeated hemorrhage and to improve prognosis, even when the AVM is only partially obliterated.11–16

With modern endovascular techniques, targeted treatment of AVM-associated aneurysms, partial nidus obliteration with flow reduction, or complete obliteration is possible in most patients with AVMs.16–19 In this article, we evaluate the results of a treatment strategy for brain AVMs that present with hemorrhage that includes early angiographic diagnosis and endovascular treatment in the acute phase.

Materials and Methods

General Management of Intracranial Hemorrhage

All patients admitted with intracranial hemorrhage not obviously appreciated as hypertensive hematomas were referred for cerebral angiography as soon as possible. Only in patients admitted in poor clinical condition who were possible candidates for emergency surgical intervention, was CTA performed first to inform about possible vascular pathology and to decide whether emergent endovascular treatment preceding surgery would be desirable.20 Cooperative patients in stable clinical condition underwent complete cerebral angiography, and when a vascular disorder amenable for endovascular therapy was diagnosed (AVM, aneurysm, or dural fistula), embolization under general anesthesia was planned on short notice. In uncooperative or intubated patients, general anesthesia was induced before angiography and embolization could follow in the same session. Angiography and embolization were performed on a biplane angiographic system (Integra BN3000 Neuro or Allura Neuro; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) equipped with 3D rotational angiography and high-speed filming.

Patients with Acutely Ruptured AVMs

In acutely ruptured AVMs, where an intranidal- or a flow-aneurysm could be identified as the likely source of bleeding, we aimed the endovascular treatment primarily at elimination of this source from the circulation with coils or Onyx (ev3, Irvine, California), when possible, followed by partial or complete obliteration of the nidus.

In acutely ruptured AVMs without an obvious source of bleeding, we intended to completely obliterate the nidus in small or intermediate-size brain AVMs that are accessible by the microcatheter and with feeders suitable for the injection with Onyx, with allowance for at least 2–3 cm of reflux. In ruptured, large AVMs, where complete endovascular obliteration is unlikely, we primarily aimed at flow reduction and partial nidus obliteration presurgery or radiosurgery. High-flow pial or intranidal fistulas were occluded with Onyx under temporary balloon occlusion of the feeding pedicle to decrease the flow and prevent migration of Onyx through the fistula into the venous side.21

After embolization, patients were transferred to an intensive care unit and cared for by a multidisciplinary team of intensivists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, anesthetists, and neuroradiologists. After clinical recovery, patients with incompletely obliterated AVMs were scheduled for additional radiosurgery or neurosurgery. Patients with completely obliterated AVMs by embolization alone were scheduled for a follow-up angiogram at 3 months.

Between January 2008 and March 2011, 23 patients presented with AVM-related intracranial hemorrhage and were treated with endovascular techniques within 10 days of the ictus. There were 16 men and 7 women, with a mean age of 42 years (median 39, range 6–74 years). All 23 patients had parenchymal hematomas with or without intraventricular or subarachnoid extension. There were 10 micro-AVMs (nidus size <1 cm; Fig 1) and 1 single-hole pial fistula (Fig 2). The remaining 12 AVMs had a mean size of 2.8 cm (range 2–4 cm). AVM location was frontal in 11 patients, occipital in 5, parietal in 2, temporal in 2, and cerebellar in 3. In 5 patients, a flow aneurysm was the likely cause of hemorrhage, and 4 patients had an intranidal aneurysm that marked the bleeding spot.

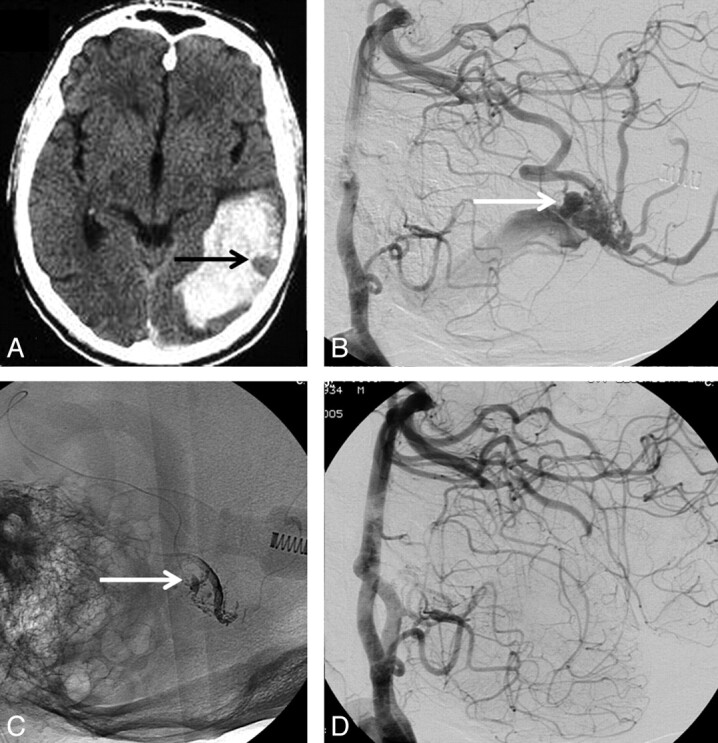

Fig 1.

71-year-old man with sudden headache and hemianopsia. A, CT scan shows posterior temporal hematoma with an outlined venous aneurysm indicating the source of the hemorrhage (arrow). B, Lateral view of vertebral angiography shows micro-AVM with intranidal aneurysm as the source of hemorrhage (arrow). C, Nonsubtracted lateral view shows Onyx cast after embolization. The intranidal aneurysm is partly filled with Onyx (arrow). D, Complete obliteration of the AVM with Onyx.

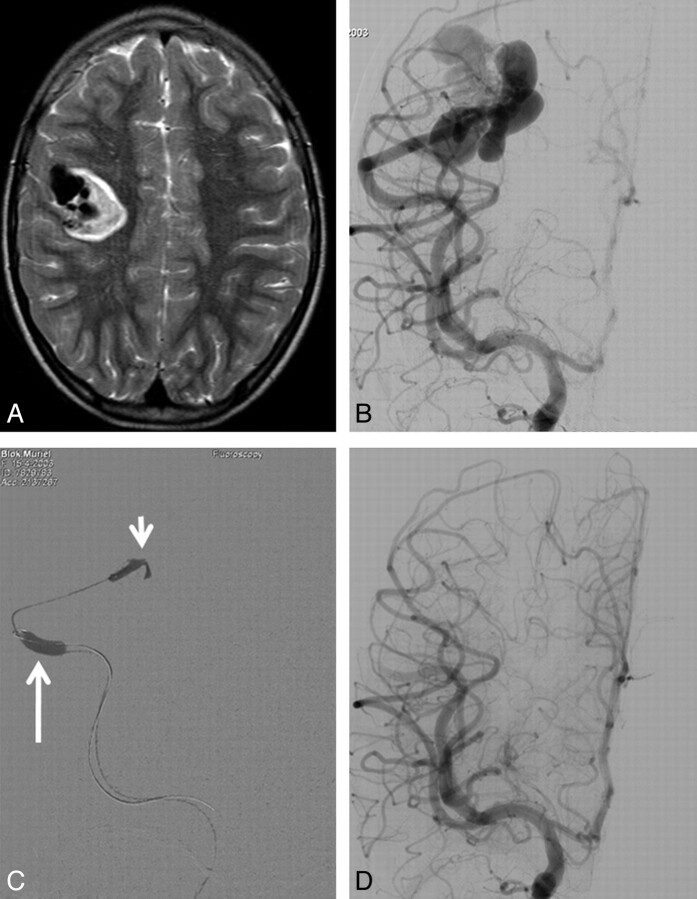

Fig 2.

6-year-old girl with sudden headache and left-sided weakness. A, T2-weighted MR imaging demonstrates intraparenchymal hematoma and flow voids indicating vascular malformation. B, Frontal view of right internal carotid angiography shows single-hole, high-flow pial fistula with dilated draining veins. C, Fluoroscopic frontal image during embolization. The fistula is occluded with Onyx (short arrow) during balloon occlusion of the feeding artery (long arrow) to block the flow and prevent migration of Onyx to the venous side of the fistula. D, Complete obliteration of the pial fistula.

Results

Results of Embolization

Complete embolization of the AVM with Onyx was achieved in 13 of 23 patients (57%; Fig 3). Eight of the 13 AVMs were micro-AVMs, and 3 had an intranidal aneurysm as the likely source of the bleeding. Partial obliteration of the AVM was achieved in 10 of 23 patients (43%). In 6 of these 10 patients, an intranidal (n = 1) or flow-aneurysm (n = 5) as the source of hemorrhage was obliterated with coils (n = 3) or Onyx (n = 3) (Fig 4). There were no complications of endovascular treatment.

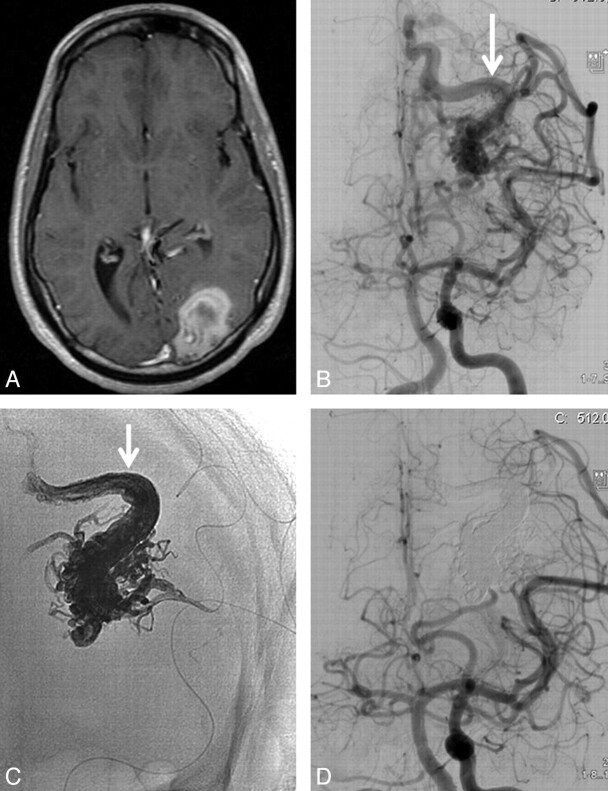

Fig 3.

23-year-old man with sudden headache and hemianopsia. A, T1-weighted MR imaging demonstrates left occipital hematoma. B, Frontal view of concomitant left internal carotid and vertebral angiogram shows small occipital AVM with a single draining vein (arrow). C, Nonsubtracted image of Onyx cast after embolization: complete filling of the nidus and proximal part of the draining vein (arrow). D, Angiography demonstrating complete obliteration of the AVM.

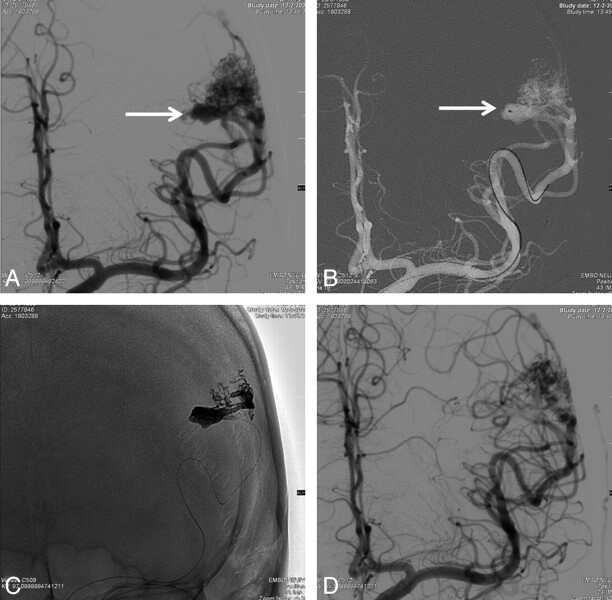

Fig 4.

49-year-old man with sudden headache and dysphasia and frontal hematoma on CT scan. A, Frontal view of left internal carotid angiogram shows small left frontal AVM with intranidal aneurysm as the source of hemorrhage (arrow). B, Fluoroscopic image during embolization with the tip of the microcatheter inside the aneurysm (arrow). C, Nonsubtracted image with Onyx cast filling the intranidal aneurysm completely. D, Small remnant of the AVM after embolization without filling of the aneurysm. The remnant was subsequently treated with gamma knife radiosurgery.

Additional Treatments and Follow-Up

One patient died of an uncontrollable rise of intracranial pressure after surgical evacuation of a frontal hematoma after complete embolization of a micro-AVM. Additional treatments of 10 patients with partially obliterated AVMs consisted of surgery in 2 and gamma knife radiosurgery in 8. In all 13 patients with completely obliterated AVMs, follow-up angiography confirmed lasting occlusion. The 22 surviving patients had a mean follow-up of 21 months (median 21, range 3–48 months). There were no new episodes of hemorrhage during this follow-up. At last follow-up, 3 patients were dependent in a nursing home and 19 patients were functioning independently.

Discussion

In this study of 23 patients with AVM-related hemorrhagic stroke, endovascular treatment in the acute phase resulted in complete obliteration of most AVMs. All 9 AVM-associated aneurysms that were considered weak spots, and the source of hemorrhage, could be excluded from the circulation. No repeated hemorrhage occurred during a mean 21 months of follow-up. Embolization of AVMs has taken a large step forward in the last decade. The introduction of the nonadhesive polymer Onyx has largely replaced the use of acrylic glue for the obliteration of the nidus in many centers. With growing experience, advanced biplane imaging with rapid subtraction fluoroscopy, and refinements of technique in the use of Onyx,17,21 most small and intermediate-size brain AVMs can be completely obliterated at a low complication rate, on the condition that the nidus is accessible by the microcatheter and with feeders suitable for the injection with Onyx with allowance of at least 2–3 cm of reflux.16–19 Better recognition of certain angioarchitectural features of the AVM as likely weak spots prone to recurrent hemorrhage, such as intranidal- and flow-related aneurysms and venous stenoses, have prompted many operators to perform a partial targeted embolization treatment when complete AVM obliteration is unlikely or impossible.7,11–15 Intranidal- and flow-related aneurysms can be excluded from the circulation with Onyx, acrylic glue, or coils, and venous outflow restrictions can be exonerated by occlusion of high-flow intranidal fistula with Onyx under flow arrest with a microballoon.21

These new developments in the treatment of brain AVMs, in combination with the concurrent and similar advancement of endovascular treatment with Onyx of dural arteriovenous fistulas with drainage to the cortical veins,22,23 have led our hospital to an adaptation of the diagnosis and treatment strategy in patients with hemorrhagic stroke. We now perform early angiography in patients who present with an intraparenchymal hematoma, except older hypertensive patients with basal ganglia or thalamus hematomas and patients with known malignant disease or impaired coagulation. Only in patients in poor clinical condition where surgical evacuation of the hematoma is considered, is CTA performed first to inform the neurosurgeon about the presence, location, and size of a possible vascular disorder. In all other patients, angiography is performed without preceding CTA, because with CTA micro-AVMs and dural fistulas, the most common causes of hemorrhagic stroke in this selected patient group, can easily be missed.20,24 Additional 3D rotational angiography provides precise information about presence, angioarchitecture, and flow of all AVMs, dural fistulas, and aneurysms, and endovascular treatment can follow immediately. For several years, we have only used Onyx for the embolization of brain AVMs, because Onyx is injected very slowly and can be better controlled then acrylic glue.

Patients with a ruptured AVM have a substantial risk of repeat hemorrhage. In a study by Mast et al,10 comprising 142 patients with a ruptured AVM, the annual rate of recurrent hemorrhage was 33% for men and 10% for women. A similar annual rate of hemorrhage is associated with dural fistula with drainage to the cortical veins. The early application of the new endovascular treatment possibilities for these aggressive lesions may improve prognosis for patients with hemorrhagic stroke by reducing or even eliminating recurrent hemorrhage. In our limited patient series, no recurrent hemorrhages occurred after early endovascular treatment. In view of this, we advocate early angiography in patients with hemorrhagic stroke in the appropriate clinical setting to diagnose or exclude, with certainty, AVMs and dural fistula as the cause of hemorrhage. At present, American and European guidelines are unclear about both the timing and the type of imaging technique for diagnosing underlying vascular pathology in adults with hemorrhagic stroke.25,26

Conclusions

Endovascular treatment with Onyx in the acute phase of hemorrhagic stroke cured most ruptured AVMs, and all AVM-associated aneurysms that were considered the source of hemorrhage could be excluded from the circulation. In patients with AVM-related hemorrhagic stroke, prompt diagnosis and treatment may improve prognosis by reducing repeat hemorrhage rate.

References

- 1. Graf CJ, Perret GE, Torner JC. Bleeding from cerebral arteriovenous malformations as part of their natural history. J Neurosurg 1983; 58: 331–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crawford PM, West CR, Chadwick DW, et al. Arteriovenous malformations of the brain: natural history in unoperated patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986; 49: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown RD, Jr, Wiebers DO, Forbes G, et al. The natural history of unruptured intracranial arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg 1988; 68: 352–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ondra SL, Troupp H, George ED, et al. The natural history of symptomatic arteriovenous malformations of the brain: a 24-year follow-up assessment. J Neurosurg 1990; 73: 387–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stapf C, Mohr JP, Choi JH, et al. Invasive treatment of unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations is experimental therapy. Curr Opin Neurol 2006; 19: 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stapf C. The rationale behind “A Randomized Trial of Unruptured Brain AVMs” (ARUBA). Acta Neurochir Suppl 2010; 107: 83–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. da Costa L, Wallace MC, Ter Brugge KG, et al. The natural history and predictive features of hemorrhage from brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke 2009; 40: 100–05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hernesniemi JA, Dashti R, Juvela S, et al. Natural history of brain arteriovenous malformations: a long-term follow-up study of risk of hemorrhage in 238 patients. Neurosurgery 2008; 63: 823–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meisel HJ, Mansmann U, Alvarez H, et al. Effect of partial targeted N-butyl-cyano-acrylate embolization in brain AVM. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002; 144: 879–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mast H, Young WL, Koennecke HC, et al. Risk of spontaneous haemorrhage after diagnosis of cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Lancet 1997; 350: 1065–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alexander MJ, Tolbert ME. Targeting cerebral arteriovenous malformations for minimally invasive therapy. Neurosurgery 2006; 59: 178–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hademenos GJ, Massoud TF. Risk of intracranial arteriovenous malformation rupture due to venous drainage impairment. A theoretical analysis. Stroke 1996; 27: 1072–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansmann U, Meisel J, Brock M, et al. Factors associated with intracranial hemorrhage in cases of cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Neurosurgery 2000; 46: 272–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stefani MA, Porter PJ, terBrugge KG, et al. Angioarchitectural factors present in brain arteriovenous malformations associated with hemorrhagic presentation. Stroke 2002; 33: 920–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krings T, Hans FJ, Geibprasert S, et al. Partial “targeted” embolisation of brain arteriovenous malformations. Eur Radiol 2010; 20: 2723–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katsaridis V, Papagiannaki C, Aimar E. Curative embolization of cerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) with Onyx in 101 patients. Neuroradiology 2008; 50: 589–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saatci I, Geyik S, Yavuz K, et al. Endovascular treatment of brain arteriovenous malformations with prolonged intranidal Onyx injection technique: long-term results in 350 consecutive patients with completed endovascular treatment course. J Neurosurg 2011; 115: 78–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andreou A, Ioannidis I, Lalloo S, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial microarteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg 2008; 109: 1091–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Brain AVM embolization with Onyx. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 172–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Delgado Almandoz JE, Romero JM. Advanced CT imaging in the evaluation of hemorrhagic stroke. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2011; 21: 197–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M. Endovascular occlusion of high-flow intracranial arteriovenous shunts: technical note. Neuroradiology 2007; 49: 1029–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M. Curative embolization with Onyx of dural arteriovenous fistulas with cortical venous drainage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 1516–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cognard C, Januel AC, Silva NA, Jr, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with cortical venous drainage: new management using Onyx. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 235–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith SD, Eskey CJ. Hemorrhagic stroke. Radiol Clin North Am 2011; 49: 27–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steiner T, Kaste M, Forsting M, et al. Recommendations for the management of intracranial haemorrhage—part I: spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. The European Stroke Initiative Writing Committee and the Writing Committee for the EUSI Executive Committee. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006; 22: 294–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Masdeu JC, Irimia P, Asenbaum S, et al. EFNS guideline on neuroimaging in acute stroke. Report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13: 1271–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]