Abstract

Background

Several studies have recently addressed factors associated with severe Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19); however, some medications and comorbidities have yet to be evaluated in a large matched cohort. We therefore explored the role of relevant comorbidities and medications in relation to the risk of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality.

Methods

All ICU COVID‐19 patients in Sweden until 27 May 2020 were matched to population controls on age and gender to assess the risk of ICU admission. Cases were identified, comorbidities and medications were retrieved from high‐quality registries. Three conditional logistic regression models were used for risk of ICU admission and three Cox proportional hazards models for risk of ICU mortality, one with comorbidities, one with medications and finally with both models combined, respectively.

Results

We included 1981 patients and 7924 controls. Hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, asthma, obesity, being a solid organ transplant recipient and immunosuppressant medications were independent risk factors of ICU admission and oral anticoagulants were protective. Stroke, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and treatment with renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone inhibitors (RAASi) were independent risk factors of ICU mortality in the pre‐specified primary analyses; treatment with statins was protective. However, after adjusting for the use of continuous renal replacement therapy, RAASi were no longer an independent risk factor.

Conclusion

In our cohort oral anticoagulants were protective of ICU admission and statins was protective of ICU death. Several comorbidities and ongoing RAASi treatment were independent risk factors of ICU admission and ICU mortality.

Keywords: anticoagulants, cohort studies., coronavirus infections, critical care, renin angiotensin system, risk factors

EDITORIAL COMMENT.

The results of this Swedish nationwide intensive care study on risk factors of COVID‐19 may be useful in policymaking on the protection of risk groups for severe COVID‐19 infection and ICU death.

1. BACKGROUND

The treatment of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) poses a major challenge for health systems. Identifying patients at risk of severe illness and potentially death is crucial for strategic planning and adequate resource allocation. Although there are few specific medicines and no vaccines for COVID‐19, several treatments have been suggested to alter the risk of severe COVID‐19.

Some studies have investigated whether renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) and other antihypertensive agents could predispose individuals to severe COVID‐19. 1 Yet, data are scarce on the effect (beneficial or harmful) of these drugs on outcome. Moreover, corticosteroids have been suggested to both elevate and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in COVID‐19. 2 , 3 Finally, because thromboembolic complications are common in COVID‐19 patients, anticoagulant treatment could be protective against severe COVID‐19. 4

Because data are limited on the role of pre‐existing diseases and medications on the risk of severe illness and death in COVID‐19 patients, we conducted a register‐based study on all Swedish COVID‐19 patients treated in an intensive care unit (ICU). These patients were compared to an age‐ and sex‐matched cohort.

Our primary outcome was the impact of pre‐COVID‐19 medications and comorbidity risk of ICU admission as a proxy for severe illness in COVID‐19. We also assessed the effect of these factors on the risk of ICU mortality.

2. METHODS

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (approval no. 2020‐02144) who also waived informed consent. The study was a priori registered with the ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04390074) and reporting follows the STROBE statement. 5

2.1. Data sources

All Swedish general ICU report all intensive care cases to the Swedish Intensive Care Registry (SIR) and all Influenza or Corona virus infected ICU patients to the SIRs subregistry, the Influenza and Virus Infection Registry (SIRI). 6 The reporting of COVID‐19 mandates a positive polymerase chain reaction test to SARS‐coronavirus‐2. All in‐ and out‐patient visits in specialized care are reported to the National Patient Register (NPR), and all dispensings of prescribed medications are reported to the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, both run by the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare. 7 The Population Statistics (RTB) of Statistics Sweden (SCB) contains demographic data on all residents of Sweden. 8

2.2. Study population

The study population was defined by a least one COVID‐19 registration in the SIRI until data acquisition on 27 May 2020. From RTB, four age‐ and sex‐matched controls per patient were drawn. Age matching was performed as close to ICU admission as possible, on the age at 31 January 2020. Cases could not become controls and controls could not be selected twice. Exclusion criteria were aged <18 years or the absence of a Swedish personal identification number (PIN). The NPR provided data on all contacts with specialized care (eg admission date, discharge date, interventions and diagnoses according to the International Codes of Diagnoses, ICD‐10) from 5 years preceding the inclusion date. Data on all dispensed drugs (such as the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical classification system (ATC) code, dose, strength, number of doses and dispensation date from 2 years preceding inclusion) were retrieved from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. We received data on intensive care interventions and status at discharge (dead or alive) from the SIR.

2.3. Statistics

For descriptive statistics, we used medians with interquartile range (IQR), counts with percentages. Differences were evaluated with the Mann‐Whitney U test and Fisher´s exact test as appropriate. In the case control cohort, we used three conditional binary logistic regression models and in the ICU discharged cohort we used three binary logistic regression models, to determine the odds ratio (OR) of ICU admission and ICU death, respectively. In the first model we assessed the impact of predefined comorbidities and in the second we assessed the effect of medications in which drug dispensation in the past 6 months preceding inclusion was used as a surrogate for drug use (Appendix 1). In the third model we combined the comorbidities model and the medications model. Immunosuppressed disease or state was then exchanged for systemic inflammatory disease and solid organ transplant recipient because immunosuppressant use, including corticosteroids, was part of the definition of an immunosuppressed state. In the medications models we adjusted for the revised Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), 9 which was used as a factor. In three corresponding Cox proportional hazards models we adjusted for gender, age and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3 (SAPS3). Age and SAPS3 were treated as continuous variables after restricted cubic spline application. Observations were censored at the date of alive ICU discharge or at the 27 may 2020, whichever occurred first. The ICD‐10 codes for comorbid diagnoses and the ATC codes for medications appear in Appendix 2.

As sensitivity analyses we performed the combined regression model analyses described above with immunosuppressant drugs and RAASi subdivided into ATC subgroups. Furthermore, we added the use of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) during ICU care to the combined Cox model to explore the influence of severe acute renal failure on the effect of RAASi on ICU mortality. Moreover, post hoc, we fitted a conditional logistic regressions model on comorbidities and medications with invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU as endpoint. Finally, we fitted a Cox model on complete cases to evaluate the imputation process. For the Cox models, missing SAPS3 and time at risk were imputed by Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) and the proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by visual inspection of plots of Schoenfeld residuals against time.

Statistical significance was set to P < .05 (two‐tailed). Data management and descriptive statistics were done using IBM SPSS software for Windows version 27 (Microsoft Inc). The regression analyses were conducted using R software version 3.5.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r‐project.org) with the survival package and the rms package. Imputations were performed with the MICE‐package and forest plots using the forestplot package.

3. RESULTS

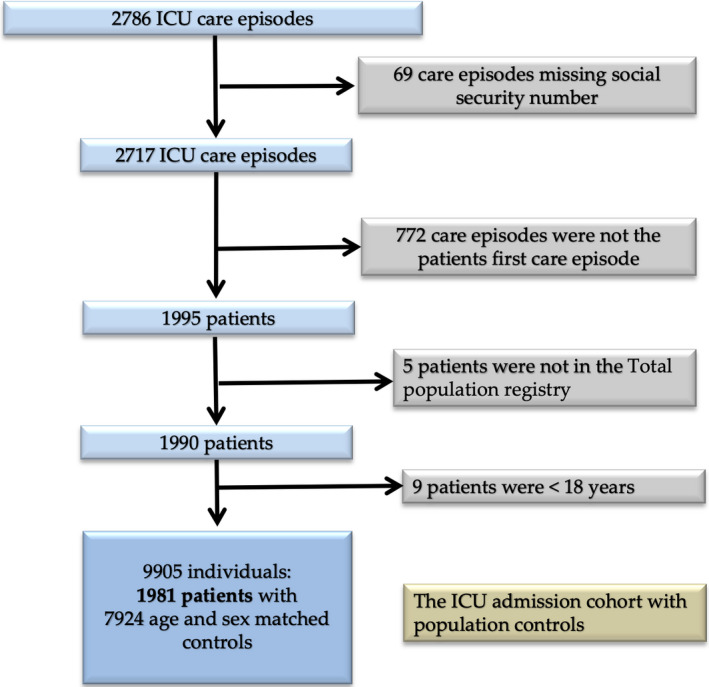

In the SIRI there were 2786 care episodes with COVID‐19 representing 1981 patients > 17 years old with a PIN included in the RTB from which 7924 population controls were drawn. On the date of data extraction, 1544 patients had been discharged from the ICU (Figure 1). Demographics, chronic and acute health status and information on the ICU care of the cohorts are described in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Patient selection flowchart. ICU: intensive care unit. Template adopted from the PRISMA‐statement 5 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients, >17 y old, admitted to Swedish ICUs, with COVID‐19, between 6th of March and 27th of May 2020 and their age and gender matched population controls

| COVID‐19 admitted to ICU | P | Controls | COVID‐19 Discharged from ICU | COVID‐19 discharged alive from ICU | P | COVID‐19 Died in ICU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1981 | 7924 | 1544 | 1198 | 346 | ||

| Female gender | 516 (26) | 1.0 | 2064 (26) | 419 (27.1) | 345 (28.7) | .006 | 74 (21.4) |

| Age at ICU‐admission (years) | 61 (52‐69) | 1.0 | 61 (52‐69) | 60 (51‐69) | 58 (50‐67) | <.001 | 67 (59 −74) |

| Hospital type | — | — | — | — | .001 | — | |

| University | 728 (36.7) | na | 645 (41.7) | 528 (44.0) | 117 (33.8) | ||

| County | 832 (42) | na | 718 (46.4) | 524 (43.7) | 194 (56.1) | ||

| District | 205 (10.3) | na | 181 (11.7) | 146 (12.2) | 35 (10.1) | ||

| SAPS3 | 53 (46‐69) | na | 53 (46‐59) | 51.5 (45‐57) | <.001 | 58 (52‐65.0) | |

| PaO2/FiO2 at admission | 13.5 (10.3‐19.2) | na | 13.6 (10.4‐19.3) | 14.0 (10.9‐19.5) | <.001 | 12.5 (8.7‐17.7) | |

| CCI score | 0 (0‐0) | <.001 | 0 (0‐0) | 0 (0‐0) | 0 (0‐0) | .189 | 0 (0‐0) |

| ICU length of stay | na | na | 10.4 (4.4‐17.3) | 10.5 (4.1‐18.0) | .74 | 10.3 (5.0‐16.6) | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | na | na | 1072 (69.3) | 772 (64.3) | <.001 | 30 (86.7) | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (h) | na | na | 258 (152‐404) | 264 (162‐409) | .01 | 238 (119‐391.3) | |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | na | na | 281 (18.9) | 227 (19.8) | .056 | 54 (15.8) | |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation (h) | na | na | 26 (9‐58.5) | 26 (9‐58.5) | .41 | 33.5 (8.75‐63.3) | |

| High flow humidified nasal oxygen | na | na | 397 (26.7) | 339 (29.6) | <.001 | 58 (17.0) | |

| High flow humidified nasal oxygen (h) | na | na | 34 (15.5‐72.5) | 40 (20‐75) | <.001 | 10 (3‐22.5) | |

| Prone positioning | na | na | 565 (38.0) | 374 (32) | <.001 | 182 (54.7) | |

| Prone position sessions | na | na | 4 (2‐6) | 3 (2‐6) | .25 | 4 (2‐7) | |

| CRRT | na | na | 227 (15.3) | 121 (10.6) | <.001 | 106 (31.1) | |

| CRRT (h) | na | na | 302 (141‐598) | 364.5 (211.8‐696.5) | .001 | 239 (96‐502) | |

| Surgical admission | 42 (2.2) | na | 49 (2.5) | 26 (2.3%) | .85 | 9 (2.6%) |

Data are presented as numbers with percentages or medians with interquartile ranges as appropriate, for interventions also as hours of intervention.

Abbreviations: CCI, revised Charlson Comorbidity Index; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; ICU, intensive care unit; P, p‐value for difference between adjacent columns; PaO2/FiO2, is the arterial partial pressure of oxygen divided by the inspired fraction of oxygen; SAPS3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.1. Risk of ICU admission

The crude occurrence of all analysed comorbid diseases were more common in the ICU‐admitted COVID‐19 patients than in the controls, except for stroke and cancer. In addition, alpha‐blockers, tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) inhibitors, interleukin inhibitors, oral anticoagulants, Lopinavir/Ritonavir and anti‐hepatitis C virus (HCV) drugs were not associated with ICU admission. All other medications were more commonly dispensed to the ICU‐admitted patients than to the controls (Table 2). Amongst the ICU discharged patients, the crude occurrence of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and being immunosuppressed were more common in deceased than in ICU survivors. For the remaining comorbidities, there were no differences. RAASi, beta‐blockers, non‐insulin antidiabetics, immunosuppressants, statins and platelet aggregation inhibitors were more commonly dispensed to patients who ultimately died in the ICU. No other differences were seen for the remaining medications analysed (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Diagnoses and medications of patients, >17 y old, admitted to Swedish ICUs, with COVID‐19, between 6th of March and 27th of May 2020, their age and gender matched general population controls and ICU discharged patients of the same cohort

| COVID‐19 admitted to ICU | P | Controls | COVID‐19 discharged alive from ICU | P | COVID‐19 Died in ICU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic heart disease | 142 (7.2) | .002 | 420 (5.3) | 69 (5.8) | .035 | 31 (9.0) |

| Non‐ischemic heart disease | 175 (8.8) | <.001 | 488 (6.2) | 96 (8.0) | .38 | 33 (9.5) |

| Hypertension | 982 (49.6) | <.001 | 2997 (37.8) | 539 (44.9) | <.001 | 211 (61.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | 40 (2.0) | .003 | 89 (1.1) | 28 (2.3) | .20 | 4 (1.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 482 (24.3) | <0.001 | 828 (10.4) | 273 (22.8) | .038 | 98 (28.3) |

| Stroke | 59 (3.0) | .126 | 188 (2.4) | 30 (2.5) | .031 | 17 (4.9) |

| Chronic Renal failure | 75 (3.8) | <.001 | 86 (1.1) | 40 (3.3) | .41 | 15 (4.3) |

| COPD | 75 (3.8) | <.001 | 146 (1.8) | 37 (3.1) | .048 | 19 (5.5) |

| Asthma | 133 (6.7) | <.001 | 128 (1.6) | 73 (3.1) | .051 | 32 (9.2) |

| Obesity | 123 (6.2) | <.001 | 138 (1,7) | 67 (5.6) | 1 | 19 (5.5) |

| Immunosuppressed | 236 (11.9) | <.001 | 439 (5.5) | 127 (10.6) | .028 | 52 (15.1) |

| Cancer | 94 (4.7) | .356 | 338 (4.3) | 52 (4.3) | .66 | 17 (4.9) |

| Inflammatory disease | 115 (5.8) | <.001 | 245 (3.1) | 63 (5.3) | .19 | 25 (7.2) |

| Solid organ transplant recipient | 24 (1.2) | <.001 | 11 (0.1) | 11 (0.9) | .24 | 6 (1.7) |

| ACE‐inhibitor | 311 (15.7) | <.001 | 930 (11.7) | 155 (12.9) | <.001 | 75 (21.7) |

| ARB | 397 (20.0) | <.001 | 1242 (15.7) | 213 (17.8) | <.001 | 94 (27.2) |

| Renin inhibitor | 0 | na | 0 | 0 | na | 0 |

| Any RAASi | 695 (35.1) | <.001 | 2144 (27.1) | 361 (30.1) | <.001 | 164 (47.4) |

| Alfa‐blocker | 18 (0.9) | .121 | 47 (0.6) | 13 (1.1) | .54 | 2 (0.6) |

| Beta‐blocker | 430 (21.7) | <.001 | 1328 (16.8) | 232 (19.3) | <.001 | 106 (30.6) |

| Antihypertensive use excluding RAASi, beta‐blockers and alpha‐blockers | 129 (6.5) | <.001 | 261 (3.3) | 74 (6.2) | .90 | 22 (6.4) |

| Antidiabetics, non‐insulin | 385 (19.4) | <.001 | 702 (8.9) | 215 (17.9) | .003 | 87 (25.1) |

| Insulin | 170 (8.6) | <.001 | 255 (3.2) | 99 (8.3) | .91 | 27 (8.3) |

| Immunosuppressive treatment, not glucocorticoids | 75 (3.8) | <.001 | 144 (1.8) | 36 (3.0) | .032 | 19 (5.5) |

| Selective immunosuppressant (L04AA) | 28 (1.4) | <.001 | 24 (0.3) | 15 (1.3) | 1.0 | 4 (1.2) |

| TNF‐α‐inhibitor (L04AB) | 10 (0.5) | .705 | 34 (0.4) | 9 (0.8) | .22 | 0 (0.0) |

| Interleukin‐inhibitor (L04AC) | 2 (0.1) | 1.0 | 8 (0.1) | 1 ( 0.1) | 1.0 | 0 (0.0) |

| Calcineurase‐inhibitor (L04AD) | 25 (1.3) | <.001 | 13 (0.2) | 12 (1.0) | .26 | 6 (1.7) |

| Other immunosuppressant (L04AX) | 51 (2.6) | .006 | 128 (1.6) | 26 (2.2) | .081 | 14 (4.0) |

| Systemic glucocorticoid treatment | 193 (9.7) | <.001 | 301 (3.8) | 103 (8.6) | .093 | 40 (11.6) |

| Immunosuppressive treatment including glucocorticoids | 223 (11.3) | <.001 | 399 (5.0) | 117 (9.8) | .018 | 50 (14.5) |

| Statins | 518 (26.1) | <.001 | 1530 (19.3) | 275 (22.9) | .001 | 110 (31.8) |

| Oral anticoagulants | 130 (6.6) | .758 | 504 (6.4) | 71 (5.9) | .31 | 26 (7.5) |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 279 (14.1) | <.001 | 840 (10.6) | 130 (10.8) | <.001 | 68 (19.7) |

| Lopinavir‐Ritonavir Ritonavir | 1 (0.1) | .488 | 2 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1.0 | 0 (0.0) |

| Anti HCV and/or Interferon | 1 (0.1) | .698 | 8 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | na | 0 (0.0) |

Data are presented as numbers with percentages.

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICU, intensive care unit; P, P‐value for difference between adjacent columns calculated by Fisher´s exact test; RAASi, renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

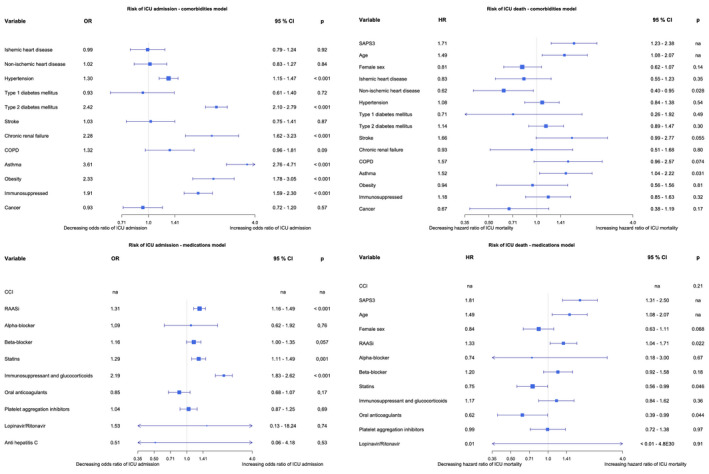

In the comorbidities logistic regression model, hypertension, T2DM, chronic renal failure (CRF), asthma, obesity and being immunosuppressed were independent risk factors for ICU admission for COVID‐19 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plots of the binary logistic regressions models over risk of ICU admission and Cox proportional hazards models over risk of ICU death. CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; RAASi, Renin‐Angiotensin‐Aldosterone System inhibitors; SAPS3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3; SAPS3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

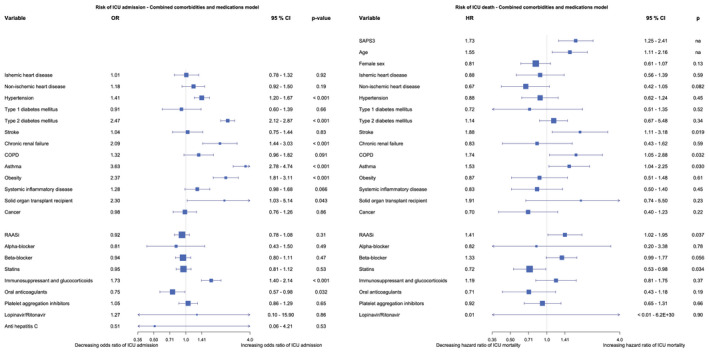

In the logistic regression model with medications RAASi, statins and immunosuppressant medication, including glucocorticoids, were independent risk factors for ICU admission. In the combined comorbidities and medication model hypertension, T2DM, CRF, asthma, obesity, being a solid organ transplant recipient and immunosuppressants, including glucocorticoid therapy, remained independent risk factors of ICU admission. In the same model anticoagulant therapy was protective of ICU admission (Figure 3). The list of oral anticoagulants used in the cohorts is found in Appendix 3. In these three conditional logistic regression models, Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Anti‐HCV and/or Interferon were excluded due to infinite beta.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plots of the binary logistic regressions models over risk of ICU admission and Cox proportional hazards models over risk of ICU death, comorbidity and medications combined. CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; RAASi, Renin‐Angiotensin‐Aldosterone System inhibitors; SAPS3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. Risk of death

In the comorbidities Cox model asthma, higher SAPS3 and age were independent risk factors of death, whereas non‐ischemic heart disease was protective. In the medications Cox model RAASi therapy, higher SAPS3 and age were independent risk factors and statins as well as oral anticoagulant therapy were protective of ICU mortality. Because of no cases with anti HCV therapy, this was excluded from the model (Figure 2). In the Cox model combining comorbidities and medications increasing SAPS3 and age, stroke, COPD, asthma and RAASi therapy remained independent risk factors of ICU death, and statins remained protective (Figure 3). Due to missing data, 256 patients had SAPS3 and 36 patients had time at risk imputed by MICE.

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

The crude occurrence of the variables used in our models, divided on the ICU admitted patients, the ICU discharged patients and the patients not yet discharged from ICU is shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics, of variables used in the models, of patients, > 17, admitted to Swedish ICUs, with COVID‐19, between 6th of March and 27th of May 2020

| ICU admitted cohort | ICU discharged cohort | P | Not yet ICU discharged patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1981 | 1544 | 437 | |

| Age | 61 (52‐69) | 60 (51‐69) | .11 | 62 (54‐69) |

| SAPS3 | 53 (46‐69) | 53 (46‐59) | .91 | 53 (46‐59) |

| Female sex | 516 (26) | 419 (27.1) | .042 | 97 (22.2) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 142 (7.2) | 99 (6.4) | .020 | 43 (9.8) |

| Non‐ischemic heart disease | 175 (8.8) | 129 (8.4) | .18 | 46 (10.4) |

| Hypertension | 982 (49.6) | 750 (48.6) | .10 | 232 (53.1) |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 40 (2.0) | 31 (2.0) | 1.00 | 9 (2.1) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 482 (24.3) | 369 (23.9) | .41 | 113 (25.9) |

| Stroke | 59 (3.0) | 47 (3.0) | .87 | 12 (2.7) |

| Chronic renal failure | 75 (3.8) | 55 (3.6) | .39 | 20 (4.6) |

| COPD | 75 (3.8) | 56 (3.6) | .48 | 19 (4.3) |

| Asthma | 133 (6.7) | 105 (6.8) | .83 | 28 (6.4) |

| Obesity | 123 (6.2) | 86 (5.6) | .032 | 37 (8.5) |

| Systemic inflammatory disease | 115 (5.8) | 88 (5.7) | .73 | 27 (6.2) |

| Solid organ transplant recipient | 24 (1.2) | 17 (1.1) | .46 | 7 (1.6) |

| Cancer | 94 (4.7) | 69 (4.5) | .31 | 25 (5.7) |

| RAASi | 695 (35.1) | 524 (33.9) | .047 | 171 (39.1) |

| Alpha‐blocker | 18 (0.9) | 15 (1.0) | .78 | 3 (0.7) |

| Beta‐blocker | 430 (21.7) | 338 (21.9) | .74 | 92 (21.1) |

| Statins | 518 (26.1) | 384 (24.9 | .016 | 134 (30.7) |

| Immunosuppressants including glucocorticoids | 223 (11.3) | 167 (10.8) | .27 | 56 (12.8) |

| Oral anticoagulants | 130 (6.6) | 97 (6.3) | .38 | 33 (7.6) |

| Thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors | 279 (14.1) | 198 (12.8) | .003 | 81 (18.5) |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1.0 | 0 (0.0) |

| Anti HCV and/or Interferon | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | .22 | 1 (0.2) |

Data are presented as numbers with percentages or median with interquartile range as appropriate.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICU, intensive care unit; P, P‐value for difference between adjacent columns calculated by Fisher´s exact test or Mann‐Whitney U test as appropriate; RAASi, renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

When immunosuppressants and RAASi were further divided into subgroups, in the combined comorbidities and medication models, corticosteroid therapy was an independent risk factor for ICU admission but not for ICU mortality. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) were not independent risk factors of ICU admission but they were risk factors of ICU mortality. (Appendix 4). After adding CRRT to a Cox model combining comorbidities and medications, RAASi was still an independent risk factor for ICU mortality (Appendix 5). When the conditional logistic regression model on risk of ICU admission was duplicated with the risk of ICU admission with invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) as endpoint hypertension, T2DM, asthma, obesity, being a solid organ recipient and treatment with Immunosuppressants including glucocorticoids were independent risk factors. For this analysis, we lacked data on IMV for 214 ICU patients. Due to infinite beta the variables Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Anti‐HCV and/or Interferon were excluded from the model (Appendix 6). Compared to the main analysis, in the Cox proportional hazards model on the 1691 complete cases, being a solid organ transplant recipient was a significant risk factor of ICU mortality and non‐ischemic heart disease was protective. Stroke was no longer a significant risk factor and Statins were no longer protective (Appendix 7).

4. DISCUSSION

The main finding in this cohort study on 1981 COVID‐19 ICU patients and 7924 age‐ and sex‐matched controls is that, not only age, sex and acute disease severity, but also several comorbidities and ongoing medications, were linked to the risk of ICU admission and ICU mortality. This is contrary with the findings of another, not yet peer reviewed, study on a very similar ICU cohort (Chew MS, Blixt P, Åhman R, Engerström L, Andersson H, Kiiski Berggren R, Tegnell A, McIntyre S). Characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to Swedish intensive care units for COVID‐19 during the first 60 days of the 2020 pandemic: a registry‐based, multicenter, observational study. Vol. 21. 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.06.20169599v1.full.pdf). In contrast with the referred study, in which the admitting physician assessed comorbidity data retrospectively, our comorbidity data were retrieved from several high quality registries who have collected their data prospectively.

Another important finding is the protective effect, vis‐à‐vis ICU admission, of oral anticoagulant therapy preceding inclusion. Anticoagulants were also protective of ICU death in the medications model; however, this protective effect disappeared after adjusting for comorbidities. These findings contradict a cohort study in 139 COVID‐19 patients on anticoagulants and 417 COVID‐19 positive propensity score‐matched controls. However, in that study the initial cohort had a high level of cases for which controls could not be found and the primary endpoint was neither ICU admission nor ICU mortality. 10 Furthermore, our findings strengthen the evidence behind treatment guidelines with anticoagulants in COVID‐19. 11 Statins have been proposed protective of severe COVID‐19 disease 12 , 13 and the protective effect of statins is reported by others regarding both ICU admission 14 and mortality, 15 , 16 but in some cohorts no such effect was seen. 17 Contrary to this, ongoing statin use in our cohort was found a risk factor of ICU admission. However, in the present study, which includes substantially more statin treated patients than the two referred to above, we did not find a protective effect on ICU admission but demonstrate a protective effect on ICU mortality. Moreover, the level of care for similar patients may vary between countries. Yet another important finding in the current study is that although obesity was a risk factor for ICU admission, it was not a risk factor for ICU death. This is in line with the findings from a smaller study assessing obesity as a risk factor of illness severity in COVID‐19 patients 18 and also studies on sepsis. 19 Furthermore, it supports the findings from a large Brazilian cohort explored for risk factors of COVID‐19 mortality. 20 Although COPD has been suggested as a risk factor for severe COVID‐19 disease, 21 this was not confirmed in our main analyses on risk of ICU admission but it was associated with ICU mortality. However, asthma was a risk factor across all analyses. Perhaps severe COPD patients are more often subject to limitations of care or we do not adjust for some protective factors related to COPD.

In contrast with previous studies, RAASi were associated with an increased risk of ICU death after adjusting for comorbidities. On the assumption that acute renal failure would be a mediator we added use of CRRT to the model. However, RAASi was still, although to a lesser extent, associated with ICU mortality, suggesting that acute renal failure could not explain the association between these. Most studies investigating the relationship between RAASi and COVID‐19 are underpowered to detect such an effect or had the risk of acquiring COVID‐19 as an endpoint. 1 One large study showed an increased crude risk of ICU admission or death in patients with RAASi and COVID‐19, but this effect was not seen after adjustment in a regression model. 22 This discrepancy between studies might reflect different cohort demographics or the method of adjustment of the models. In light of the report of the Dexamethasone arm of the RECOVERY trial, 3 the finding that ongoing immunosuppressant treatment and more specifically glucocorticoid treatment is a risk factor of ICU care is intriguing. We speculate that this is a matter of timing. The adverse effects of long‐term corticosteroid treatment as well as a possible negative effect of corticosteroid induced immunosuppression in the early phases of the COVID‐19 disease might be causative; however, this needs to be confirmed in future studies. Lastly, in several studies diabetes mellitus has been a risk factor of severe COVID‐19 and/or death 18 , 23 ; however, in our cohort the risk increase of ICU admission is solely represented by type 2 diabetes mellitus contrary with previous works. 24 COVID‐19 has been reported being a risk factor of ischemic stroke in previous studies 25 and stroke has been linked to COVID‐19 mortality in a general population cohort. 26 Here, we report that previous stroke is a risk factor of COVID‐19 related ICU mortality.

One important limitation of the present study is that patients with an indication for ICU care may not be admitted because of capacity strain and care limitations. High age and severe comorbidities are reasons for such limitations, which might skew the results. However, this constraint is inherent in ICU care. The surge might also have altered usual indication of ICU care with an increased use of high flow oxygen and noninvasive mechanical ventilation on the hospital wards. To address this we performed a sensitivity analysis on patients with IMV during ICU. This conditional logistic regression rendered the same results as our primary analysis on ICU admission apart from oral anticoagulants not being protective. However, for a significant proportion of the ICU‐admitted patients we lack information on IMV, which might affect the results. In addition, the control population was not matched for residence, which may affect the prevalence of the tested prognostic factors that vary somewhat between different parts of Sweden. 27 However, these differences may have been related to age differences between regions of Sweden and for our study we used age‐matched controls. Lastly, the lack of data on frailty, which is an important risk factor of ICU mortality, especially in the aged, 28 is also an important limitation.

This study has several strengths. We compared the COVID‐19 ICU population to a relevant control cohort of the general population to create a robust dataset for analysis of risk factors and protective factors of severe COVID‐19 defined by ICU admission and death. The cohort and all data in our dataset are derived from high‐quality national registries with a low rate of missing data. We believe that this approach is superior to identifying controls by a negative COVID‐19 test, which is a common strategy used by others. 1 , 29 We sought to include severe COVID‐19 and the low median arterial partial oxygen pressure divided by the fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) at ICU admission suggests severe hypoxic respiratory failure in the ICU‐admitted cohort. Moreover, the high proportion of invasively ventilated patients amongst the dataset is also proof of a high degree of a physiological disorder. Lastly, we had a relatively high degree of missing SAPS3 data. The missingness is due to the fact that 437 patients were still not discharged at date of data collection and that several ICUs report SAPS3 data to the SIR only after ICU discharge of the patient. We chose to impute these data due to the high risk of bias related to the missingness. The stability of the imputation was tested with a sensitivity analysis on complete cases. The results of this model were consistent with the complete cases model, but differed in the effect on outcome for being a solid organ transplant recipient and previous stroke. These variables had few observations and wide 95% CI. Also non‐ischemic heart disease and previous use of statins differed between the complete vs imputed models. Common to these variables was that their statistical interpretation was sensitive to small changes in the dataset. Due to this we have a high confidence in our results, especially for the majority of the variables that did not change their effect over the sensitivity analysis.

5. CONCLUSION

This nationwide matched cohort study on risk factors of COVID‐19 found that ongoing therapy with anticoagulants is protective of COVID‐related ICU admission and ongoing therapy with statins were protective of ICU death. In addition, T2DM, CRF, asthma, obesity, being a solid organ recipient and ongoing immunosuppression were independent risk factors for ICU admission. Increasing age, stroke, COPD and asthma were associated with ICU death, as was ongoing treatment with RAASi. Our findings may be useful in policy‐making on the protection of risk groups of severe COVID‐19 infection and ICU death and warrant further research on anticoagulation and RAASi in COVID‐19 disease.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Supporting information

Ahlström B, Frithiof R, Hultström M, Larsson I‐M, Strandberg G, Lipcsey M. The swedish covid‐19 intensive care cohort: Risk factors of ICU admission and ICU mortality. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65:525–533. 10.1111/aas.13781

Funding information

This study was funded by Uppsala University Hospital research fund and the Centre for Clinical Research at Region Dalarna, Sweden.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this study are available from the SIR, the NPR and the SCB. However, privacy or ethical restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study. Thus, these data are not publicly available. The data, however, are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the SIR, the Swedish board of health and welfare and the SCB.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mackey K, King VJ, Gurley S, et al. Risks and Impact of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin‐receptor blockers on SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:195‐203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang Z, Liu J, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Zhao Q, Liu J. The effect of corticosteroid treatment on patients with coronavirus infection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:13‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid‐19 ‐ preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020:NEJMoa2021436. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19: An updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE). Statement. Epidemiology. 2007;18:800‐804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hillgren J. The Swedish Intensive Care Registry year‐report 2019 [Internet]. Karlstad (SE). 2020. Available from: https://www.icuregswe.org/globalassets/arsrapporter/arsrapport_2019_final.pdf

- 7. Sverige . Socialstyrelsen . Registers ‐ Swedish national board of health and welfare [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2020 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics‐and‐data/registers/

- 8. Populations Statistics (RTB) [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/vara‐tjanster/bestalla‐mikrodata/vilka‐mikrodata‐finns/individregister/registret‐over‐totalbefolkningen‐rtb/

- 9. Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676‐682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tremblay D, van Gerwen M, Alsen M, et al. Impact of anticoagulation prior to COVID‐19 infection: a propensity score‐matched cohort study. Blood. 2020;136:144‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Susen S, Tacquard CA, Godon A, et al. Prevention of thrombotic risk in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 and hemostasis monitoring. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):364. 10.1186/s13054-020-03000-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee KCH, Sewa DW, Phua GC. Potential role of statins in COVID‐19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:615‐617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rizk JG, Kalantar‐Zadeh K, Mehra MR, Lavie CJ, Rizk Y, Forthal DN. Pharmaco‐immunomodulatory therapy in COVID‐19. Drugs. 2020;80:1267‐1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan WYT, Young BE, Lye DC, Chew DEK, Dalan R. Statin use is associated with lower disease severity in COVID‐19 infection. Sci Rep. 2020;10:17458. 10.1038/s41598-020-74492-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossi R, Talarico M, Coppi F, Boriani G. Protective role of statins in COVID 19 patients: importance of pharmacokinetic characteristics rather than intensity of action. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:1573‐1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez‐Nava G, Trelles‐Garcia DP, Yanez‐Bello MA, Chung CW, Trelles‐Garcia VP, Friedman HJ. Atorvastatin associated with decreased hazard for death in COVID‐19 patients admitted to an ICU: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID‐19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1345‐1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ebinger JE, Achamallah N, Ji H, et al. Pre‐existing traits associated with Covid‐19 illness severity. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0236240. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ng PY, Eikermann M. The obesity conundrum in sepsis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:4‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soares RCM, Mattos LR, Raposo LM. Risk factors for hospitalization and mortality due to COVID‐19 in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:1184‐1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lippi G, Henry BM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): COPD and COVID‐19. Respir Med. 2020;167:105941. 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2441‐2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aggarwal G, Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Henry BM, Sanchis‐Gomar F. Diabetes mellitus association with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) severity and mortality: a pooled analysis. J Diabetes. 2020;12:851‐855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Apicella M, Campopiano MC, Mantuano M, Mazoni L, Coppelli A, Del Prato S. COVID‐19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:782‐792. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fifi JT, Mocco J. COVID‐19 related stroke in young individuals. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:713‐715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID‐19‐related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430‐436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gémes K, Talbäck M, Modig K, et al. Burden and prevalence of prognostic factors for severe COVID‐19 in Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:401‐409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Flaatten H, De Lange DW, Morandi A, et al. VIP1 study group . The impact of frailty on ICU and 30‐day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1820‐1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mehta N, Kalra A, Nowacki AS, et al. Association of use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1020‐1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the SIR, the NPR and the SCB. However, privacy or ethical restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study. Thus, these data are not publicly available. The data, however, are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the SIR, the Swedish board of health and welfare and the SCB.