Abstract

Objective

Since the beginning of the COVID‐19 epidemic, a large number of guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of COVID‐19 have been developed, but the quality of those guidelines and the consistency of recommendations are unclear. The objective of this study is to evaluate the quality of the diagnosis and treatment guidelines on COVID‐19 and analyze the consistency of the recommendations of these guidelines.

Methods

We searched for guidelines on diagnosis and/or treatment of COVID‐19 through PubMed, CBM, CNKI, and WanFang Data, from January 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020. In addition, we also searched official websites of the US CDC, European CDC and WHO, and some guideline collection databases. We included diagnosis and/or treatment guidelines for COVID‐19, including rapid advice guidelines and interim guidelines. Two trained researchers independently extracted data and four trained researchers evaluated the quality of the guidelines using the AGREE II instruments. We extracted information on the basic characteristics of the guidelines, guideline development process, and the recommendations. We described the consistency of the direction of recommendations for treatment and diagnosis of COVID‐19 across the included guidelines.

Results

A total of 37 guidelines were included. Most included guidelines were assessed as low quality, with only one of the six domains of AGREE II (clarity of presentation) having a mean score above 50%. The mean scores of three domains (stakeholder involvement, the rigor of development and applicability) were all below 30%. The recommendations on diagnosis and treatment were to some extent consistent between the included guidelines. Computed tomography (CT), X‐rays, lung ultrasound, RT‐PCR, and routine blood tests were the most commonly recommended methods for COVID‐19 diagnosis. Thirty guidelines were on the treatment of COVID‐19. The recommended forms of treatment included supportive care, antiviral therapy, glucocorticoid therapy, antibiotics, immunoglobulin, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), convalescent plasma, and psychotherapy.

Conclusions

The methodological quality of currently available diagnosis and treatment guidelines for COVID‐19 is low. The diagnosis and treatment recommendations between the included guidelines are highly consistent. The main diagnostic methods for COVID‐19 are RT‐PCR and CT, with ultrasound as a potential diagnostic tool. As there is no effective treatment against COVID‐19 yet, supportive therapy is at the moment the most important treatment option.

Keywords: clinical practice guideline, COVID‐19, diagnosis, treatment

1. INTRODUCTION

It has been almost one year since the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak started. As of October 28, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported more than 43 million confirmed cases and about 1 163 000 deaths, 1 which has taken an incalculable toll on several countries. Until now, there is no effective treatment for COVID‐19, and potential vaccines are also only under development. The optimal approach to diagnosis and treatment of COVID‐19 is uncertain. Some medications are so far only recommended for patients with severe COVID‐19 or in the context of clinical trials. The recommendations also differ between sources. For example, the WHO interim guidance 2 did not suggest routinely giving systemic corticosteroids for treatment of COVID‐19 outside clinical trials, but another international guideline 3 suggested that corticosteroids should be given to patients with severe COVID‐19 and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). Different institutions have recommended differing diagnostic methods for COVID‐19 for different populations, which lead to confusion in their clinical use.

High‐quality clinical practice guidelines can regulate the diagnosis and treatment behavior of health providers and improve the quality of medical services. Guidelines are also equally important for public health emergencies. After the outbreak of COVID‐19, several institutions including WHO, National Health Commission (China), Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), European Center for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC), as well as several scientific/professional associations, societies and hospitals, developed a large number of clinical practice guidelines including rapid advice guidelines and interim guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of COVID‐19.4,5 However, due to the urgency of the situation, the quality of those guidelines and the consistency of recommendations are unclear. Previous studies 6 , 7 have shown that the clinical guidelines of COVID‐19 lacked detail and covered a narrow range of topics. Another study 8 suggested inconsistency between some recommendations of some clinical practice guidelines compared with those of the WHO. To our knowledge no study has yet systematically compared the recommendations of COVID‐19 diagnosis and treatment guidelines, for quality and consistency. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the quality of COVID‐19 diagnosis and treatment guidelines developed exclusively for COVID‐19, and compare the similarities and differences in the diagnostic and treatment recommendations of these guidelines.

2. METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cross‐sectional analysis of diagnosis and treatment guidelines on COVID‐19. Before the study began, the reviewers familiarized themselves with the methodological appraisal tool for guidelines via AGREE II 9 (Appraisal of Guidelines, for Research, and Evaluation).

2.1. Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), CBM (China Biology Medicine disc, CBMdisc), CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), and WanFang Data from January 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020 to identify the diagnosis and treatment guidelines on COVID‐19, using the terms guideline, statement, guidance, recommendation, COVID‐19, 2019‐nCoV, SARS‐CoV‐2, novel coronavirus, novel coronavirus pneumonia. We also searched the official websites of WHO (https://www.who.int/), US CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/), ECDC (https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/home), CCDC (http://www.chinacdc.cn), and the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China (http://en.nhc.gov.cn), as well as Google Scholar and the reference lists of included guidelines. We did not search preprint servers because we wanted to include only final versions of guidelines that are already applied in clinical practice. The search strategy is given in the Supporting material.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included diagnosis and/or treatment guidelines for COVID‐19, including rapid advice guidelines and interim guidelines. A diagnostic and/or treatment guideline was defined as a guideline that contains diagnostic and/or treatment elements in their recommendations. If the guideline was published in both English language and Chinese language, we only included the English‐language version. If there were multiple versions of the guidelines, we only included the latest one.

We excluded the following types of documents: (1) comprehensive or general guidelines that addressed COVID‐19, but were not exclusive; (2) guidelines published only as a book; (3) proposals of guidelines; (4) guidelines not for humans; (5) translations, interpretations, and abstracts of guidelines; (6) diagnosis or treatment guidelines for disability, sequelae, complications or other symptoms caused by novel coronavirus; (7) diagnosis or treatment guidelines for other diseases caused by SARS‐CoV‐2; (8) Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) guidelines; (9) guidelines for which we were unable to retrieve the full text; and (10) guidelines not published in English or Chinese.

2.3. Study selection

We used Endnote X9 for literature storage and screening. Two trained researchers (YL, ML) screened independently first by the titles and abstracts. Two researchers (YL, ML) independently screened records from the official websites manually. Discrepancies were solved by a third researcher (XL). Full text reviewing was done by one researcher (XL).

2.4. Data extraction

For each eligible diagnosis and treatment guideline, we extracted the following data: (1) basic characteristics of the guidelines (eg, title, publication date, country/setting, type of guideline); (2) characteristics of the developer and development process of the guideline (eg, the developer institution or journals, whether a systematic review was conducted, whether the evidence was formally graded, system of evidence grading); and (3) recommendations (diagnosis and treatment details). Two reviewers (XL, ML) independently extracted the data, which were then checked by a third person (YL). Disagreements were solved through discussion or with the help of a fourth author (YC).

2.5. Quality assessment of guidelines

We used the AGREE II tool to evaluate the quality of the included guidelines. The tool consists of 23 key items divided into six domains. Each item is assigned a score from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The score for each domain was obtained by adding up the scores of all the items in the domain (of each assessor) and normalizing them (score obtained – minimum possible score)/(maximum possible score – minimum possible score). Each guideline was independently assessed by four reviewers. We calculated the mean scores for each domain across all guidelines, as well as for guidelines developed in each country, territory or area separately.

2.6. Data analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses of the general characteristics of the included guidelines. We used SPSS 14.0 to calculate the mean quality scores of included guidelines. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to test interrater reliability among the four reviewers on the AGREE II scores. We compared and analyzed the direction of recommendations related to the diagnosis and treatment on COVID‐19. Finally, we summarized the current diagnosis and treatment recommendations for COVID‐19 and examined consistency among recommendations on various diagnostic and therapeutic options.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

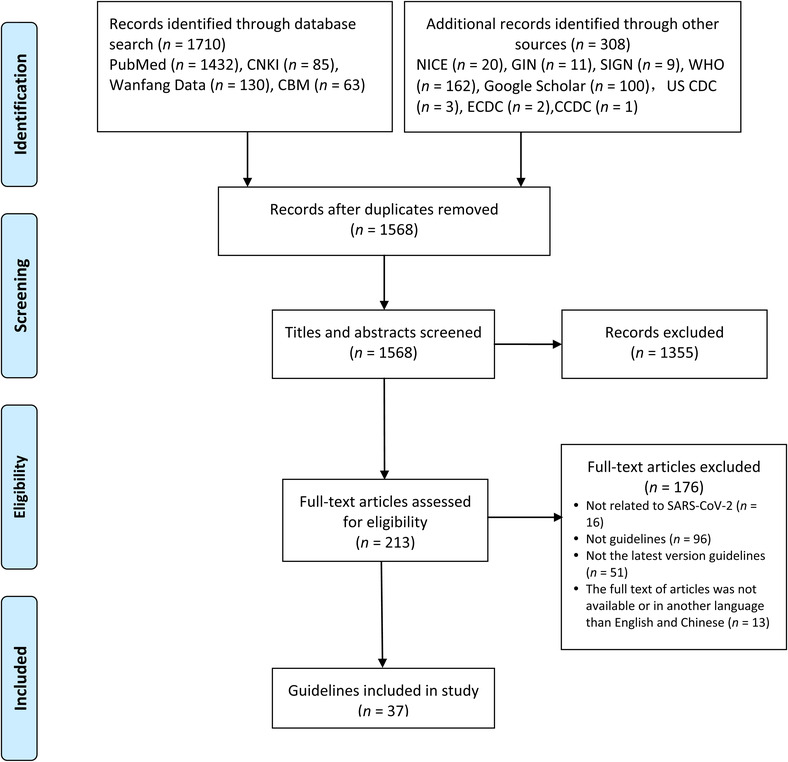

A total of 2018 articles were identified, and 37 records 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 were finally included after successive screening, including 32 guidelines 4 , 5 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 (86.5%) published in English language and five 10 , 12 , 13 , 21 , 24 (13.5%) in Chinese language (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of study selection process

3.2. Characteristics of the included guidelines

Of the 37 guidelines included, ten 4 , 14 , 20 , 30 , 32 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 (27.0%) were developed by international panels (Table 1). Nine8,10‐13,15,21,24,34,44 of included guidelines were developed in China (24.3%), five 21 , 26 , 35 , 36 , 44 (13.5%) in the United States, two in Australia 38 , 42 (5.4%), two in Canada22 43(5.4%), two in South Korea17,33 (5.4%), and one each in Germany, 25 India, 16 Italy, 19 Mexico, 31 North America (USA and Canada), 26 Poland, 29 and Spain. 27 These guidelines were published between January 30 and August 27, 2020.

TABLE 1.

The characteristics of the included diagnosis and treatment guidelines for COVID‐19

| Full title | Journal or other publication platform | Publication date | Country, territory or area of development | Development institute or organization | Patients | Type of guideline | Type of evidence basis | Method for evaluating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of the novel coronavirus pneumonia infections (3rd Edition) [in Chinese] | Herald of Medicine | 30‐Jan‐2020 | China | Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) | Military Medical Research | 6‐Feb‐2020 | China | Center for Evidence‐Based and Translational Medicine, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | GRADE |

| Guideline for imaging diagnosis of novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (1st edition 2020) [in Chinese] | New Medicine | 25‐Feb‐2020 | China | Chinese Society of Radiology | Adults and children | Diagnosis | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| Rapid screening and practice guidelines for suspected and confirmed cases of novel coronavirus infection/pneumonia in children[in Chinese] | Chinese Journal of Evidence Based Pediatrics | 25‐Feb‐2020 | China | Children's Hospital of Fudan University | Children with COVID‐19 | Treatment | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | GRADE |

| Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID‐19 disease is suspected | WHO website | 13‐Mar‐2020 | International | WHO | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | Unclear |

| Diagnosis and clinical management of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection: an operational recommendation of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (V2.0) | Emerging Microbes & Infections | 14‐Mar‐2020 | China | Peking Union Medical College Hospital | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Guidelines on clinical management of COVID‐19 | India Government website | 17‐Mar‐2020 | India | Government of India Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Directorate General of Health Services | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | unclear | NR |

| Guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Korea | Annals of Laboratory Medicine | 25‐Mar‐2020 | South Korea | Korean Society for Laboratory Medicine, COVID‐19 Task Force and the Center for Laboratory Control of Infectious Diseases, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Adults and children | Diagnosis | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Management of critically ill adults with COVID‐19 | The Journal of the American Medical Association | 26‐Mar‐2020 | International | Surviving Sepsis Campaign | Critically ill adult patients with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | GRADE |

| The Italian coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: recommendations from clinical practice | Anaesthesia | 27‐Mar‐2020 | Italy | The European Airway Management Society | Adults and children | Treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Physiotherapy management for COVID‐19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations | Journal of Physiotherapy | 30‐Mar‐2020 | International | Multidisciplinary international panel | Adults and children | Treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Guidelines for imaging diagnosis of novel coronavirus pneumonia (2nd Edition 2020, shortened version)[in Chinese] | Journal of Capital Medical University | 31‐Mar‐2020 | China | Committee of the Infectious Diseases Radiology Section of Chinese Medical Doctor Association | Adults and children | Diagnosis | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| Clinical management of patients with moderate to severe COVID‐19 ‐ interim guidance | Canada Government website | 2‐Apr‐2020 | Canada | Public Health Agency of Canada | Patients with moderate to severe COVID‐19 | Treatment | Adapted based on WHO guideline | Unclear |

| Corticosteroid guidance for pregnancy during COVID‐19 pandemic | American Journal of Perinatology | 9‐Apr‐2020 | USA | Medical College of Wisconsin | Pregnant women with COVID‐19 | Treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Radiological diagnosis of COVID‐19: expert recommendation from the Chinese Society of Radiology (First edition) [in Chinese] | Chinese Journal of Radiology | 10‐Apr‐2020 | China | Chinese Society of Radiology | Adults and children | Diagnosis | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| German recommendations for critically ill patients with COVID‐19 | Medizinische Klinik Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin Notfmed | 14‐Apr‐2020 | Germany | Experts panelist | Critically ill patients with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Multicenter initial guidance on use of antivirals for children with COVID‐19/SARS‐CoV‐2 | Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society | 22‐Apr‐2020 | North America (USA and Canada) | Experts panelist | Children with COVID‐19 | Treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Recommendations on the clinical management of the COVID‐19 infection by the «new coronavirus» SARS‐CoV2 | Anales de Pediatría (English Edition) | 25‐Apr‐2020 | Spain | Spanish Paediatric Association | Children with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) | Clinical Infectious Diseases | 27‐Apr‐2020 | USA | Infectious Diseases Society of America | Adults and children | Treatment | Systematic review | GRADE |

| Management of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: recommendations of the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists as of March 31, 2020 | Polish Archives of Internal Medicine | 30‐Apr‐2020 | Poland | Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| Rapid advice guidelines for management of children with COVID‐19 | Annals of Translational Medicine | 1‐May‐2020 | International | Multidisciplinary international panel | Children with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Rapid review | GRADE |

| Recommendations for the management of critically ill adult patients with COVID‐19 | Gaceta Medica de Mexico | 14‐May‐2020 | Mexico | Unclear | Critically ill adult patients with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Treatment of patients with nonsevere and severe coronavirus disease 2019: an evidence‐based guideline | Canadian Medical Association Journal | 19‐May‐2020 | International | Multidisciplinary international panel | Patients with nonsevere and severe COVID‐19 | Treatment | Systematic review | GRADE |

| Clinical management of COVID‐19 interim guidance | WHO website | 27‐May‐2020 | International | WHO | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Rapid review | Revised GRADE |

| Interim guidelines on antiviral therapy for COVID‐19 | Infection & Chemotherapy | 1‐Jun‐2020 | South Korea | the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, the Korean Society for Antimicrobial Therapy, and the Korean Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases | Adults and children | Treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | IDSA |

| Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus | World Journal of Pediatrics | 1‐Jun‐2020 | China | the National Clinical Research Center for Child Health, National Children's Regional Medical Center, Children's Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine | Children with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of the novel coronavirus pneumonia in the elderly in China | Aging Medicine (Milton) | 9‐Jun‐2020 | China | Experts panelist | Elderly patients with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | NR |

| Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID‐19 | Clinical Infectious Diseases | 16‐Jun‐2020 | USA | Infectious Diseases Society of America | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic review | GRADE |

| Interim guidelines for management of confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) clinical care guidance | US CDC website | 30‐Jun‐2020 | USA | US CDC | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| COVID‐19 PICU guidelines: for high‐ and limited‐resource settings | Pediatric Research | 7‐Jul‐2020 | International | Multidisciplinary international panel | Children with COVID‐19 | Treatment | Existing guidelines, consensus documents | Unclear |

| Public Health Laboratory Network Guidance for serological testing in COVID‐19 | Australian Government website | 20‐Jul‐2020 | Australia | Public Health Laboratory Network | Adults and children | Diagnosis | Available evidence | NR |

| Clinical management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in pregnancy: recommendations of WAPM‐World Association of Perinatal Medicine | Journal of Perinatal Medicine | 21‐Jul‐2020 | International | World Association of Perinatal Medicine | Pregnant women with COVID‐19 | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic retrieval of currently available evidence | NR |

| Use of chest imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID‐19: a WHO rapid advice guide | Radiology | 30‐Jul‐2020 | International | WHO | Adults and children | Diagnosis | Systematic review | GRADE |

| Remdesivir for severe COVID‐19: a clinical practice guideline | The British Medical Journal | 30‐Jul‐2020 | International | Multidisciplinary international panel | Patients with severe COVID‐19 | Treatment | Systematic review | GRADE |

| PHLN guidance on laboratory testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 (the virus that causes COVID‐19) | Australian Government website | 10‐Aug‐2020 | Australia | Public Health Laboratory Network | COVID‐19 patients | Diagnosis | unclear | NR |

| Clinical management of patients with COVID‐19: second interim guidance | Canada Government website | 17‐Aug‐2020 | Canada | Government of Canada | Adults and children | Treatment | Adapted from a WHO guideline | Reported but unclear |

| Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) treatment guidelines | NIH website | 27‐Aug‐2020 | USA | National Institutes of Health (NIH) | Adults and children | Diagnosis and treatment | Systematic review | NIH criteria |

Abbreviations: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NR, not reported; US CDC, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; WHO, World Health Organization.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.3. Quality of the included guidelines

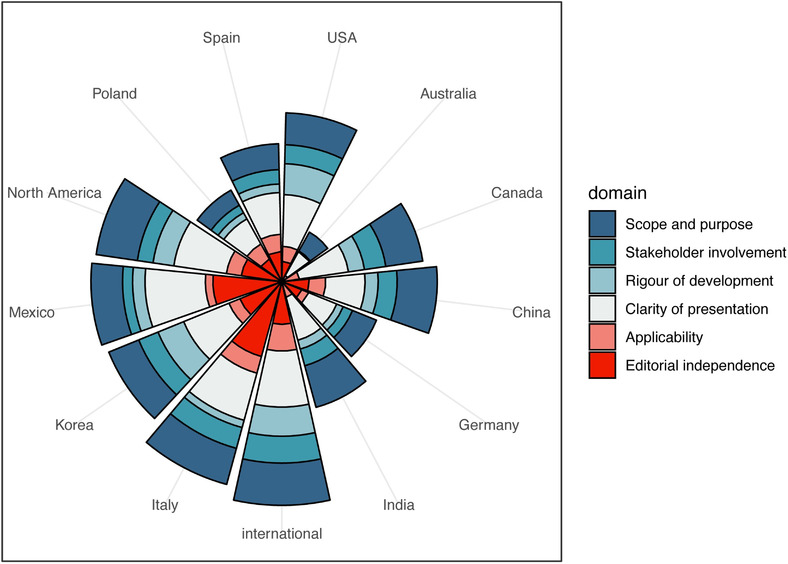

The ICC between the four reviewers for AGREE II assessment in the study was 0.925 (95%CI, 0.907‐0.938). The quality of the most included guidelines was in general low, and the mean score over all guidelines was above 50% in only one domain (clarity of presentation). Three domains (stakeholder involvement, rigor of development and applicability) had a mean score below 30% over the guidelines. The guidelines developed by multicountry international panels had the highest scores, whereas the guidelines from Poland, Germany, and Australia had the lowest scores (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

AGREE II scores by domain and area development of the included guidelines. The different sectors represent guidelines developed in different countries or areas, and the colors the six domains of the AGREE‐II tool. The radial coordinates represent the scores of the AGREE‐II tool

3.4. Recommendations for diagnosis

Twenty‐five 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 44 guidelines (67.6%) provided COVID‐19 diagnosis‐related recommendations, including seven guidelines 12 , 17 , 21 , 24 , 38 , 40 , 42 (18.9%) that contained only diagnostic recommendations. Computed tomography (CT), reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR), X‐rays, lung ultrasound, and routine blood tests were the most frequently recommended tests for COVID‐19 diagnosis (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Consistency analysis of the diagnostic recommendations of the COVID‐19 guidelines

|

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

CT was recommended for the diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19 in all except three guidelines5,30,39: one for children, one for pregnant women, and one for adults and children. The recommendation against CT was because of the variability in chest imaging findings, chest radiograph or CT alone was not recommended for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. Two guidelines12,21 (5.4%) suggested using high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT) for infants and the elderly. One guideline 24 recommended volume CT scan as the preferred choice for early detection of lesions and assessment of the nature and extent of the lesion.

RT‐PCR testing was used as a preferred testing or conditional recommendation in fourteen guidelines. 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 42 Of course, it was not recommended in some cases, such as when WHO guidelines suggesting RT‐PCR testing was not available or available, but results were delayed.

Nine guidelines5,12,14,15,21,24,27,29,39 (24.3%) referred to X‐rays for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. Six guidelines12,14,15,21,27,29 (16.2%) conditionally suggested using X‐rays, as they were often used in primary care with symptoms indicating lung involvement. However, three guidelines5,24,39(8.1%) did not recommend performing X‐rays since radiologic findings in COVID‐19 were not specific and overlapped with other infections or the high rate of fail to diagnosis.

Lung ultrasound and blood test were recommended in six guidelines 14 , 15 , 16 , 27 , 31 , 34 (16.2%). Three guidelines 14 , 16 , 31 suggested lung ultrasound used in screening and following up of COVID‐19. Three guidelines 15 , 27 , 34 suggested blood test as the routine test way.

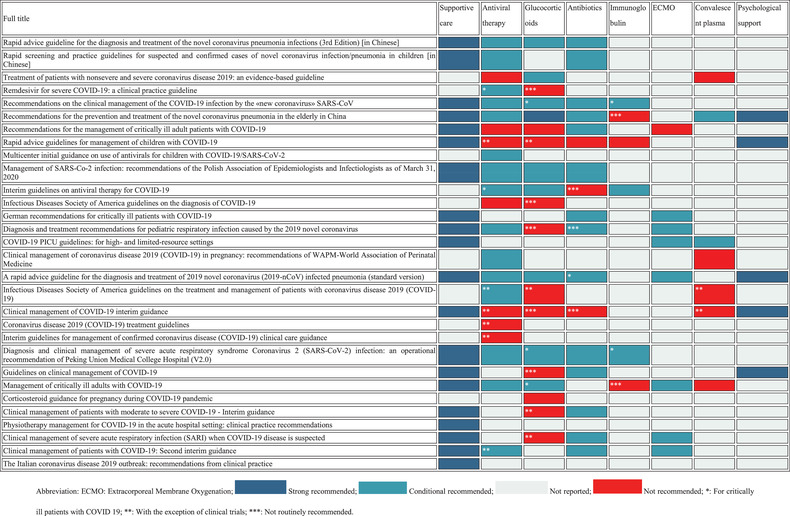

3.5. Recommendations for treatment

A total of 30 guidelines 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 44 (81.1%) addressed the treatment of COVID‐19. Treatment options included supportive care, antiviral therapy, glucocorticoid therapy, antibiotics, immunoglobulin, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), convalescent plasma, and psychotherapy (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Consistency analysis of the treatment recommendations of the COVID‐19 guidelines

|

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Recommendations on supportive care were consistent. Twenty guidelines 4 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 43 (54.1%) recommended using supportive care, mainly rest in bed, ensuring adequate calories, maintaining water‐electrolyte balance, oxygen therapy, symptomatic treatment, and nutritional supplements.

Recommendations on antiviral therapy varied across the included guidelines. Twenty‐two guidelines 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 15 , 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 44 (59.5%) referred to antiviral therapy, whereas 15 guidelines 10 , 11 , 13 , 15 , 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 , 43 (40.5%) were consistent in recommending that there were no effective antivirals currently available. Antiviral therapy may be considered for severe or critically ill patients with COVID‐19, or when conducting clinical trials. Antiviral drugs most commonly mentioned in the guidelines were alpha‐interferon, lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, umifenovir, favipiravir, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, oseltamivir, chloroquine, and tocilizumab. One international guideline suggested not to use ribavirin, umifenovir, favipiravir, lopinavir‐ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, interferon‐α and interferon‐β for neither nonsevere or severe patients with COVID‐19, but another Spanish guideline 27 suggested that in severe cases requiring hospital admission, considering initiating treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir, or remdesivir if available, may be useful for severe cases. Meanwhile, the guideline developed by Mexico 31 emphasized that there was neither a specific antiviral treatment for patients with COVID‐19, nor any results of controlled trials supporting the use of any. For children, pregnant women and elderly patients, recommendations in using antiviral treatment were also inconsistent.

Twenty guidelines 4 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 41 (54.1%) addressed the use of glucocorticoids for patients with COVID‐19. Nine 4 , 14 , 16 , 22 , 28 , 30 , 34 , 36 , 41 (24.3%) of these did not recommend routinely using the glucocorticoids or except in the context of clinical trials. The remaining nine guidelines 10 , 11 , 15 , 18 , 27 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 35 conditionally recommended the use of glucocorticoids in specific conditions, such as for critically ill patients with COVID‐19. The glucocorticoids often mentioned in these guidelines included methylprednisolone and dexamethasone.

The use of antibiotics during COVID‐19 treatment was also a common topic. We found a total of 17 guidelines 4 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 22 , 24 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 43 (45.9%), either recommending or specifically not recommending the use of antibiotics in patients with COVID‐19. Most of these guidelines 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 43 (n = 14, 37.8%) conditionally recommended starting an empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotic therapy when patients were suspected to have a bacterial superinfection or when their condition got worse. However, a prophylactic antibiotic therapy or routine treatment with antibiotics was not recommended in any guideline.

A total of six guidelines 15 , 18 , 27 , 30 , 33 , 35 (16.2%) referred to the use of immunoglobulins in patients with COVID‐19. Most of these guidelines did not advocate the routine use of immunoglobulins, but mentioned that they may be used for critically ill or elderly patients with COVID‐19 to boost their levels of immunoglobulin.

Five guidelines 4 , 18 , 28 , 32 , 39 (13.5%) on COVID‐19 treatment did not recommend using convalescent plasma because of insufficient evidence to support its use. However, one guideline 35 (2.7%) from China suggested that plasma treatment could be used as appropriate for patients with fast progression, severe cases, or critical cases. Another guideline 37 suggested that convalescent plasma treatment should be offered only within a research framework or on a compassionate basis for critically ill children with COVID‐19.

Other mentioned treatments included psychotherapy and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Seven guidelines 11 , 14 , 18 , 25 , 34 , 37 , 43 (18.9%) conditionally suggested using the ECMO. One guideline 31 specifically recommended not to use ECMO: according to the guideline, recent reports had found high mortality in patients with COVID‐19 treated with this form of organ support, suggesting ECMO should not be used in hospitals other than reference or high‐volume centers, and whose personnel have no experience with this procedure. Five guidelines 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 (13.5%) recommended psychotherapy, including psychological counseling, administration of antidepressants, and related projects.

4. DISCUSSION

We evaluated the quality of 37 diagnosis and treatment guidelines 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 for COVID‐19 and analyzed the consistency of their recommendations. In general, we found these guidelines to be of low quality. Their recommendations for treatment and diagnosis were somewhat consistent, but there were differences in the recommendations considering some specific populations and conditions.

Our results suggested that the quality of diagnosis and treatment guidelines for COVID‐19 was low, especially regarding stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, and applicability. This was generally consistent with the findings of two earlier studies. 6 , 7 There are three potential reasons for this. First, in the first eight months of the COVID‐19 epidemic, most guidelines were rapid advice guidelines or interim guidance, and the low quality may be a result of the urgency and lack of time. However, the quality of the guidelines has increased over time. Second, some of the included guidelines were published on websites only, reported with insufficient details resulting in low quality. Third, some of the AGREE II items (eg, item 7) are not necessarily applicable to the evaluation of the rapid advice guidelines, which may also have contributed to the low quality of some of the guidelines. In addition, the lack of sufficient and direct evidence to support the guidelines in the early stages of the COVID‐19 epidemic also contributes to the poor quality, the quality of evidence for guidelines based need to be improved. 45 To improve the quality of guidelines developed in such urgent situations, guideline developers should learn how to develop rapid advice guidelines in public health emergencies. Guideline users should also learn how to quickly assess the quality of public health emergencies guidelines in order to better guide public health and clinical practice.

An accurate diagnosis of COVID‐19 is essential to confirm the suspected cases. About two‐thirds of the included guidelines focused on the diagnosis of COVID‐19. Laboratory tests such as nucleic acid testing were recommended as routine tests. The turn‐around time of these tests ranges from 1 hour to a couple of days; this depends on the version of the PCR and the capacity of the laboratories. Furthermore, due to the low concentration of virus, RT‐PCR is less sensitive for diagnosis of early SARS‐CoV‐2 and presymptomatic patients, resulting in false‐negative results. For imaging diagnosis, for different populations, some guidelines recommended X‐rays, and some guidelines recommended CT scanning, depending on the population. X‐rays have a high rate of missed diagnosis for mild disease, but CT is associated with a high dose of radiation and there is a risk of low specificity. Point‐of‐care ultrasound (POCUS) has been considered as a safe and effective bedside option in the initial evaluation, management, and monitoring of disease progression in patients with confirmed or suspected COVID‐19 infection. 46 A review from Buda et al 47 showed that POCUS could be considered for patients with suspected COVID‐19 whose PCR test result is negative. Besides, ultrasound examination may be worth considering because of its convenience, low cost, and safety (compares with CT scanning).

We found the guidelines to have become more consistent in recommending diagnostic methods, as COVID‐19 has become better understood over time and diagnostic test studies have been conducted. Overall, RT‐PCR should be the first considered method of diagnosis. In the case of a negative of RT‐PCR but clearly ill and/or high‐risk patients, combinations of different diagnostic methods for different populations and settings may be considered, taking into account the cost, accessibility, and efficacy of the diagnostic methods.

At this time, there are no effective drugs for the treatment of COVID‐19. The most common treatment options remain symptomatic treatment and support therapy. The most frequently mentioned types of treatment were antiviral treatments (59.5%), supportive care (54.1%), and glucocorticoid therapy (54.1%). However, the use of these drugs or options is in most cases conditional, for example, recommended only for patients with severe COVID‐19 or for the elderly, or contraindicated for some specific populations. In the absence of sufficient or direct evidence, the recommendations for all drugs remain largely consistent. Our findings were consistent with those of Snawerdt et al, 48 who summarized the results of previously published studies and concluded that there remains no treatment that had proven to be efficacious against COVID‐19. But at the same time, a large number of systematic reviews identifying different treatments for COVID‐19 have been published. 49 , 50 , 51 Many clinical trials for the treatment of COVID‐19 52 had also been registered on ClinicalTrials.gov platform. On the one hand, these trials and reviews can provide evidence for future guidelines, but on the other hand, low‐quality or duplicate studies can lead to wasted research resources. 53 In the absence of effective treatment drugs, a vaccine is likely to be the most effective measure to end the epidemic. In the meantime, preventing and controlling the spread of COVID‐19 is paramount, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries and countries with fragile health systems.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze and evaluate the diagnosis and treatment guidelines for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. We used a systematic searching method, summarized recommendations, evaluated the quality of the guidelines, and examined the consistency of recommendations. However, this study also has several limitations. First, the searching time was up to August 31, 2020, and some guidelines that are still under development or have not yet been indexed may have been omitted. Second, we only analyzed and evaluated the COVID‐19 diagnosis and treatment guidelines. However, guidelines for COVID‐19 in combination with other diseases can also inform clinical decision‐making. Third, due to the diversity of contents in the guidelines, we were unable to extract and analyze all recommendations.

In conclusion, the current diagnosis and treatment guidelines for COVID‐19 are of low quality. The recommendations in diagnosis and treatment guideline for COVID‐19 are to be relatively consistent in their directions, particularly regarding the treatment. Up to now, there is no effective drug for the treatment of COVID‐19, and a vaccine is probably the only way to end the epidemic.

FUNDING

This study was supported by a 2020 Key R & D project of Gansu Province. Special funding for prevention and control of emergency of COVID‐19 from Key Laboratory of Evidence‐Based Medicine and Knowledge Translation of Gansu Province (Grant No. GSEBMKT‐2020YJ01).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, literature retrieval, screening, and data extraction, XL, YL, and ML; quality assessment, YL, MR, and XZ; writing‐original draft preparation, XL and YL; writing‐review and editing, XL, YL, EJ, ML, QW, YS, JLM, HS.A, MSL, YC; supervision, XL and YL; project administration, YC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Material

Luo X, Liu Y, Ren M, et al. Consistency of recommendations and methodological quality of guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID‐19. J Evid Based Med. 2021;14:40–55. 10.1111/jebm.12419

Authors Xufei Luo and Yunlan Liu contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed October 29 2020).

- 2. World Health Organization . Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID‐19 disease is suspected: interim guidance, March 13 2020. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331446/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2020.4-chi.pdf (accessed September 15 2020).

- 3. Ye Z, Rochwerg B, Wang Y, et al. treatment of patients with nonsevere and severe coronavirus disease 2019: an evidence‐based guideline. CMAJ. 2020;192:E536‐E545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO . Clinical management of COVID‐19 interim guidance. 2020, Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance. (accessed September 15 2020).

- 5. US CDC. Interim Guidelines for management of confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) clinical care guidance. 2020, Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/guidance-list.html?Sort=Date%3A%3Adesc (accessed September 15 2020).

- 6. Dagens A, Sigfrid L, Cai E, et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the COVID‐19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020;369:m2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao S, Cao J, Shi Q, et al. COVID‐19 evidence and recommendations working group. A quality evaluation of guidelines on five different viruses causing public health emergencies of international concern. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kow CS, Capstick T, Zaidi STR, Hasan SS. Consistency of recommendations from clinical practice guidelines for the management of critically ill COVID‐19 patients. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2020:ejhpharm‐2020‐002388. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2020-002388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839‐842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen T, Chen G, Guo W, et al. Rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of the novel coronavirus pneumonia infections (3rd edition). Herald Med. 2020;39:305‐307. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jin Y, Cai L, Cheng Z, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res. 2020;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Committee of the Infectious Diseases Radiology Group of Chinese Society of Radiology , et al. Guideline for imaging diagnosis of novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (1st edition 2020). New Med. 2020;30:22‐34. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Children's Hospital of Fudan University . Rapid screening and practice guidelines for suspected and confirmed cases of novel coronavirus infection/pneumonia in children. Chin J Evid‐Based Pediatr. 2020;15:1‐4. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sterne JAC, Diaz J, Villar J, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with COVID‐19: a structured summary of a study protocol for a prospective meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Trials. 2020;21:734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li T. Diagnosis and clinical management of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection: an operational recommendation of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (V2.0). Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:582‐585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. 14. Government of India Ministry of Health & Family Welfare , Directorate General of Health Services (EMR Division) . Guidelines on clinical management of COVID‐19. 2020. Available from: https://www.india.gov.in/ (accessed September 15 2020).

- 17. Hong KH, Lee SW, Kim TS, et al. Guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2020;40:351‐360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poston JT, Patel BK, Davis AM. Management of critically ill adults with COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020;323:1839‐1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sorbello M, El‐Boghdadly K, Di Giacinto I, et al. The Italian coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: recommendations from clinical practice. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:724‐732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas P, Baldwin C, Bissett B, et al. Physiotherapy management for COVID‐19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations. J Physiother. 2020;66:73‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H, Liu S, Xu H, et al. Guidelines for imaging diagnosis of novel coronavirus pneumonia (second edition 2020, shortened version). J Cap Med Univ. 2020(2):168‐173. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Public Health Agency of Canada . Clinical management of patients with moderate to severe COVID‐19—interim guidance. 2020, Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/sr/srb.html?cdn=canada&st=s&num=10&langs=en&st1rt=1&s5bm3ts21rch=x&q=Clinical+Management+of+Patients+with+Moderate+to+Severe+COVID-19+-+Interim+Guidance&_charset_=UTF-8&wb-srch-sub= (accessed September 15 2020).

- 23. McIntosh JJ. Corticosteroid guidance for pregnancy during COVID‐19 pandemic. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:809‐812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chinese Society of Radiology, Chinese Medical Association . Radiological diagnosis of COVID‐19: expert recommendation from the Chinese Society of Radiology (first edition). Chin J Radiol. 2020(04):279‐285. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kluge S, Janssens U, Welte T, Weber‐Carstens S, Marx G, Karagiannidis C. German recommendations for critically ill patients with COVID 19. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020:1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chiotos K, Hayes M, Kimberlin DW, et al. Multicenter initial guidance on use of antivirals for children with COVID‐19/SARS‐CoV‐2. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020:piaa045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Calvo C, López‐Hortelano MG, Vicente JCC, Martínez JLV; Grupo de trabajo de la Asociación Española de Pediatría para el brote de infección por Coronavirus, colaboradores con el Ministerio de Sanidad. Recommendations on the clinical management of the COVID‐19 infection by the «new coronavirus» SARS‐CoV2. Spanish Paediatric Association working group. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2020;92:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adarsh B, Rebecca LM, Amy HS, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Flisiak R, Horban A, Jaroszewicz J, et al. Management of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: recommendations of the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists as of March 31, 2020. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130:352‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu E, Smyth RL, Luo Z, et al. Rapid advice guidelines for management of children with COVID‐19. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ñamendys‐Silva SA, Cherit GD. Recommendations for the management of critically ill adult patients with COVID‐19. Gac Med Mex. 2020;156:246‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ye Z, Rochwerg B, Wang Y, et al. Treatment of patients with nonsevere and severe coronavirus disease 2019: an evidence‐based guideline. CMAJ. 2020;192:E536‐E545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim SB, Huh K, Heo JY, et al. Interim guidelines on antiviral therapy for COVID‐19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52:281‐304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen ZM, Fu JF, Shu Q, et al. Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus. World J Pediatr. 2020;16:240‐246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen Q, Wang L, Yu W, et al. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of the novel coronavirus pneumonia in the elderly in China. Aging Med (Milton). 2020;3:66‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hanson KE, Caliendo AM, Arias CA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID‐19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kache S, Chisti MJ, Gumbo F, et al. COVID‐19 PICU guidelines: for high‐ and limited‐resource settings. Pediatr Res. 2020. 10.1038/s41390-020-1053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Public Health Laboratory Network . Public Health Laboratory Network Guidance for serological testing in COVID‐19. 2020. Available from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/Publications-13 (accessed September 15 2020).

- 39. Api O, Sen C, Debska M, et al. Clinical management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in pregnancy: recommendations of WAPM‐World Association of Perinatal Medicine [published online ahead of print, 2020 July 21]. J Perinat Med. 2020. 10.1515/jpm-2020-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Akl EA, Blazic I, Yaacoub S, et al. Use of chest imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID‐19: a WHO rapid advice guide [published online ahead of print, 2020 July 30]. Radiology. 2020:203173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rochwerg B, Agarwal A, Zeng L, et al. Remdesivir for severe COVID‐19: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2020;370:m2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Public Health Laboratory Network . PHLN guidance on laboratory testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 (the virus that causes COVID‐19). 2020. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/phln-guidance-on-laboratory-testing-for-sars-cov-2-the-virus-that-causes-covid-19 (accessed September 15 2020).

- 43. Government of Canada . Clinical management of patients with COVID‐19: second interim guidance. 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/clinical-management-covid-19.html. (accessed 15 Sep 2020).

- 44. National Institutes of Health (NIH) . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) treatment guidelines. 2020, Available from: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/ (accessed September 15 2020). [PubMed]

- 45. Yao L, Sun R, Chen YL, et al. The quality of evidence in Chinese meta‐analyses needs to be improved. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:73‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Convissar DL, Gibson LE, Berra L, Bittner EA, Chang MG. Application of lung ultrasound during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:345‐350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Buda N, Segura‐Grau E, Cylwik J, Wełnicki M. Lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of COVID‐19 infection—a case series and review of the literature. Adv Med Sci. 2020;65:378‐385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Snawerdt J, Finoli L, Bremmer DN, Cheema T, Bhanot N. Therapeutic options for the treatment of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). Crit Care Nurs Q. 2020;43:349‐368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang TH, Chou CY, Yang YF, et al. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effectiveness and safety of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID‐19 patients. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020. 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Ge L, et al. Drug treatments for COVID‐19: living systematic review and network meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Verdugo‐Paiva F, Izcovich A, Ragusa M, Rada G. Lopinavir‐ritonavir for COVID‐19: a living systematic review. Medwave. 2020;20:e7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhu RF, Gao YL, Robert SH, Gao JP, Yang SG, Zhu CT. Systematic review of the registered clinical trials for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Transl Med. 2020;18:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Luo X, Lv M, Wang X, Chen Y. Avoidable waste of research on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Material