Abstract

Goblet cells are specialized epithelial cells that are essential to the formation of the mucus barriers in the airways and intestines. Armed with an arsenal of defenses, goblet cells can rapidly respond to infection but must balance this response with maintaining homeostasis. Whereas goblet cell defenses against bacterial and parasitic infections have been characterized, we are just beginning to understand their responses to viral infections. Here, we outline what is known about the enteric and respiratory viruses that target goblet cells, the direct and bystander effects caused by viral infection and how viral interactions with the mucus barrier can alter the course of infection. Together, these factors can play a significant role in driving viral pathogenesis and disease outcomes.

Keywords: airway goblet cell, enteric virus, intestinal goblet cell, mucus secretion, respiratory virus

Goblet cells are tasked with maintaining the mucus barrier at mucosal sites throughout the body. In this review, we examine how both direct and bystander effects caused by enteric and respiratory viral infection can lead to pathogenesis, with emphasis on mucus–virus and host–microbe interactions that can alter infection and disease.

Abbreviations

- CLCA1

Calcium‐activated chloride channel regulator 1

- FCGBP

Fc gamma binding protein

- HA

Hemagglutinin

- IL

Interleukin

- Math1

Mouse atonal BHLH transcription factor 1

- MuAstV

Murine astrovirus

- MUC

Mucin

- NA

Neuraminidase

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- SARS‐CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SPDEF

SAM pointed domain‐containing ETS transcription factor

- TMEV

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus

- ZG16

Zymogen granule 16

Introduction

Mucosal barrier sites throughout the body are tasked with coordinating the cellular response that distinguishes friend from foe while balancing homeostasis with a rapid response to infection [1]. Central to this balance are the epithelial cells that line these barriers, providing a plethora of heterogeneous, specialized cells that act as first responders to incoming pathogens. A common feature across mucosal sites is another layer of defense provided by mucus, a carbohydrate‐rich, gel‐like substance that, at its most basic level, prevents invading pathogens from reaching the underlying epithelium [2]. Goblet cells are specialized secretory cells that are the primary producers of the mucus barrier in the airways and intestines [3]. Their secretory milieu and overall function at these sites are dependent on contextual cues, including multimicrobe interactions. In fact, microbiota are key to these mucosal functions [4, 5], as mucus barrier defects are well documented in germ‐free [6] and antibiotic‐treated mice [7, 8]. Microbial sensing by goblet cells [6, 9, 10] and neighboring cells plays a role in shaping the mucus barrier. For example, in the presence of microbes, enterocytes in the small intestine secrete the metalloprotease, meprin β, which cleaves mucin (MUC) and enables its unfolding and full expansion [11]. However, both host responses to pathogens and the pathogens, including viruses, themselves can trigger a breakdown of this host–microbe crosstalk, with some pathogens adopting ways to modulate goblet cell numbers and functions. Whereas substantial work has been focused on the protective and disease‐mediating features of goblet cells during bacterial and parasitic infections, we are just beginning to understand their functions in the context of viral infections. The purpose of this review is to highlight what is known about the direct and indirect consequences of viral infection for goblet cells, as well as the effect of mucus interactions with viruses in the intestinal and respiratory tracts.

Goblet cell development

Goblet cells were first discovered in the early to mid‐nineteenth century and were characterized by their distinct morphology, which resembles a drinking goblet [12]. This cellular architecture is largely the result of the apical cytoplasm being full of secretory granules containing MUCs and other secretory factors, which causes the nucleus and other organelles to be pushed to the basal ‘goblet stem’. In the intestinal crypts, promotion of Atonal BHLH transcription factor 1 (ATOH1, Math1 in mice) expression and Notch inhibition drives the development of secretory progenitor cells, which then receive additional signals that turn on SAM pointed domain‐containing ETS transcription factor (SPDEF) to drive transcriptional programming, resulting in mature goblet cells that are fully differentiated [13, 14]. In the airways, goblet cells arise from a slightly different pathway, with increasing Notch signals and expression of SPDEF, which drives full differentiation and promotes mucus secretion [15, 16, 17]. The act of secretion is thought to be similar across goblet cells at these two mucosal sites, and it is characterized by either a constitutive or regulated process to maintain homeostasis [2, 3]. Regulated secretion involves vesicle secretion and also a stimulus‐driven form that is mediated by compound exocytosis characterized by rapid release of secretory granules [3, 18, 19]. Whereas regulated secretion has been characterized for airway goblet cells [20], less is understood about the signaling cascade that drives compound exocytosis. Neither secretory pathway has been precisely defined in the gut, but reactive oxygen species generation, autophagy, and inflammasome signaling appear to play a role in goblet cell secretion in mice [9, 21, 22, 23]. The details of these mechanisms have yet to be worked out in humans, but there is evidence of species‐specific differences, such as regional expression of the NLPR6 inflammasome [24, 25]. Secretory processes are also largely mediated by known secretagogues, or stimuli that drive secretion, including acetylcholine, carbachol, and histamine [26, 27, 28]. In addition, goblet cell differentiation and secretion are sensitive to cytokine stimulation [29], including Th2 signaling via Interleukin (IL)‐4 and IL‐13 [30, 31, 32]. For these reasons, goblet cells and mucus secretion can quickly mobilize as part of the innate immune response in the intestines and airways.

Intestinal goblet cells

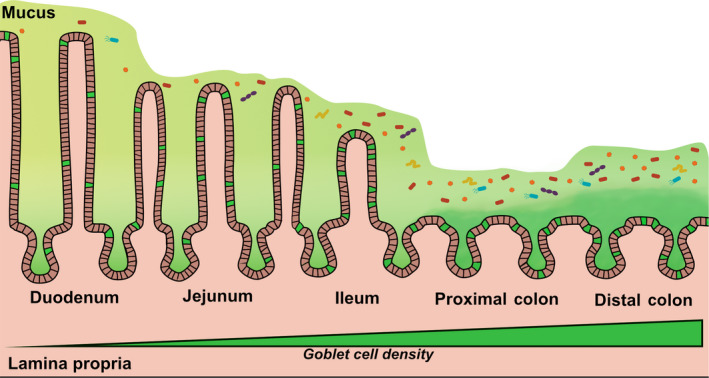

A progressive examination along the length of the intestinal tract reveals a correlative gradient between goblet cells and the microbiota, with the highest density of both being found in the distal colon (Fig. 1). The small intestine has a single, discontinuous layer of mucus, which has not been extensively measured in humans but in mice, ranges from 500 µm in the duodenum to 200 µm in the ileum [27, 33, 34]. In contrast to the small intestine, the large intestine has dual layers—an adherent inner layer below a looser outer layer [2]. In the mouse colon, the attached inner layer is ~ 50 µm thick whereas the top layer is thicker in the proximal region (50 µm) than in the distal region (10 µm) [27, 33, 34]. In human colons, the inner mucus thickness is 200–300 µm in humans [26, 35, 36, 37, 38], whereas the outer layer is ~ 400 µm in the colon [36, 39]. These mucus layers are critical for keeping microbes and other luminal contents at a safe distance from the underlying epithelium, with some commensal microbes inhabiting the outer region, creating a symbiotic environment that prevents self‐digestion [2]. Goblet cells tasked with maintaining this host barrier do so primarily through regulated secretion, but a subset of cells are thought to be primed for rapid secretion to flush out bacterial, parasitic, and even fungal infections [1, 40]. MUC2 is the main component of the secreted gel‐forming mucus in the intestines, whereas MUC1, MUC3, MUC4, MUC12, MUC13, and MUC17 are expressed as transmembrane glycoproteins [2]. MUC undergo extensive O‐linked glycosylation and other posttranslational modifications [2, 4] (Fig. 2). Although the precise molecular mechanisms and triggers that alter these modifications remain poorly defined in the context of infection, it is intriguing to consider that goblet cells can tailor MUC structure in response to a given pathogen. Further studies in this area are greatly needed.

Fig 1.

The epithelia that line the intestinal tract include specialized secretory cells known as goblet cells, highlighted in green, which increase in density from the proximal to the distal end of the tract. The small intestine (the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) is coated with a single, discontinuous mucus layer (light green), whereas the large intestine (the proximal and distal colon) is coated with an inner mucus layer (dark green) and an outer layer (light green). Microbiota, shown in confetti colors, reside within the lumen and mucus layer away from the epithelium and exhibit a density gradient that mirrors that of goblet cells.

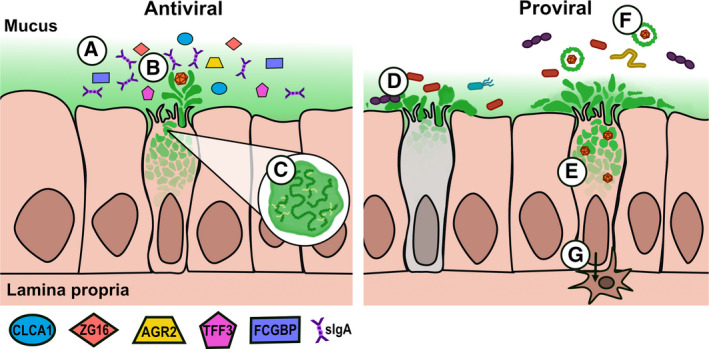

Fig 2.

Goblet cells have an arsenal of defenses at their disposal. A) Mucus consists of MUC, antimicrobial proteins with unknown antiviral potential, and also secretory IgA, which modulates gut microbiota and can combat viral infection. B) Mucus can flush out viruses or bind them to block receptor interactions. C) The composition of mucus can be changed via posttranslational modification. However, viruses have found ways to co‐opt goblet cells and mucus to their benefit, resulting in proviral effects. D) Increasing mucus secretion could lead to goblet cell exhaustion represented by the gray‐colored goblet cell), leading to barrier defects that can result in inflammation and/or secondary bacterial infection. E) Viruses may directly infect actively secreting goblet cells, potentially facilitating viral egress and dissemination in mucus. F) Viruses may bind to mucus to enhance their stability, infection, transmission, and possibly immune evasion. G) Beyond these functions of goblet cells, viruses could serve as a trigger for goblet cell‐associated pathways, which in turn could serve as mechanisms of tolerance or translocation outside the gut.

Besides MUC, goblet cells also secrete a multitude of other proteins that enhance the mucus barrier and have direct antimicrobial activities (Fig. 2). These proteins include calcium‐activated chloride channel regulator 1 (CLCA1) [41, 42], Fc gamma binding protein (FCGBP) [43], anterior gradient 2 (AGR2) [44], zymogen granule 16 (ZG16) [45], and trefoil factor 3 [46], although the antiviral functionality of these secreted proteins has yet to be elucidated. Mucus also serves as a conduit for defensins and other antimicrobial proteins and peptides secreted by Paneth cells located at the base of the crypts [47], as well as IgA, which play dual roles in modulating interactions with commensal microbes [48] and protection from pathogens [49]. Overall, with this arsenal of defenses, goblet cells can play an active role in the response to infection and have the potential to modify their response to combat‐specific pathogens.

Goblet cells and enteric viral infection

Some of the earliest reports of enteric viruses targeting goblet cells and neighboring epithelial cells in the gut relied on electron microscopy to identify virus particles. Examples include reports of ‘reovirus‐like’ virus in an infant with nonbacterial diarrhea [50], mouse adenovirus 2 in experimentally infected mice [51], and bovine coronavirus infection in calves [52]. Most recently, a number of ‘mini‐gut’ models have been developed using induced or embryonic pluripotent stem cells to generate organoids that contain both epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations, as well as colonoids and enteroids, which are derived from intestinal crypt cells in the colon and small intestine, respectively, but lack a mesenchymal cell layer [53]. Together, these models can form both spherical and 2‐D cell layers that reflect the tissue architecture and physiology of the intestinal villi and have increased our understanding of enteric viral infection in secretory cell types because immortalized intestinal cell lines frequently do not reflect the diverse epithelial heterogeneity found in vivo [53]. For example, the study of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, a coronavirus that causes high mortality in neonatal pigs, has been limited by the lack of a robust cell culture model, but it was recently shown that multiple intestinal cell types, including goblet cells, in enteroids and colonoids are infected by this virus, which mirrors the infection in vivo [54].

Enteroid models have also been used extensively in the study of human enteric viruses, giving a sense of their goblet cell propensities in vivo. Human adenovirus species C (prototype strain 5p) was the first virus identified as preferentially infecting a subset of goblet cells in enteroids; however, this cell tropism was strain specific, and a preference for goblet cells was not observed with human adenovirus species F (prototype strain 41p) [55]. Enterovirus 71 was also shown to have a strong preference for goblet cells in 2‐D epithelial monolayers derived from human fetal small intestinal crypts [56]. The infection drove a reduction in MUC1 and MUC2 expression, highlighting the ability of this virus to alter goblet cell function and, perhaps, combat mucus flushing from the gut [56]. The human astrovirus VA1 species has also been shown to infect goblet cells and other epithelial cell types in human enteroids [57]. Interestingly, murine astrovirus (MuAstV) appears to have an even higher propensity for goblet cells. This was first detected by in situ hybridization and electron microscopy and then confirmed by single‐cell transcriptional profiling of small intestinal epithelial cells [58]. Based on the transcriptional activity in goblet cells, MuAstV was determined to target actively secreting cells specifically and to drive a further increase in the expression of Muc2, Clca1, Fcgbp, and Zg16, as well as an increase in mucus thickness between and at the tops of the villi. These data indicate that MuAstV might benefit from causing this host pathway to produce more mucus in response to infection, perhaps as a means of facilitating virus egress and/or dissemination [58]. MuAstV infection also drove a change in microbiome composition and reduced colonization by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, an adherent bacterial pathogen [58]. To what extent the increase in mucus secretion is sustained after MuAstV is cleared from the gut remains to be determined, but goblet cell exhaustion has been reported after parasitic infections that similarly drive hypersecretion [59, 60]. This is a critical finding, given that such exhaustion can lead to a weakened mucus barrier, which could result in inflammation or even secondary bacterial infection [61]. In fact, this increased susceptibility to bacterial infection has been proposed as a disease mechanism for porcine epidemic disease virus, which causes goblet cell depletion in neonatal pigs [61]. Therefore, the combined effects of virus‐driven changes in goblet cells can alter the microbiome and potentially exacerbate gastrointestinal illness, as well as alter host susceptibility to other enteric pathogens (Fig. 2).

Even in the absence of direct infection, enteric viruses can drive substantial changes in goblet cell abundance, function, and differentiation. For example, whereas enterocytes undergo apoptosis after rotavirus infection in mice, goblet cell numbers are decreased in the duodenum and jejunum as a result of delayed intestinal repair [62]. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus, a coronavirus that causes significant mortality in neonatal pigs, also indirectly affects goblet cells by infecting Paneth cells in the crypt and causing a loss of Notch signals required for neighboring stem cells to regenerate enterocytes and mitigate villus blunting [63]. Instead, the loss of Notch signals drives an increase in goblet cell numbers and mucus production after infection [63]. Similar to the effect seen with porcine epidemic virus, these alterations in goblet cells result in increased susceptibility to enterotoxigenic E. coli [64]. Much like bacteria that co‐opt MUC interactions to enhance colonization [65, 66], the increase in mucus production caused by transmissible gastroenteritis virus is beneficial to the virus because binding the sialic acid‐rich MUC helps to facilitate receptor interactions [67, 68]. Indeed, a similar process has been described for the picornavirus Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), which binds to terminal sialic acid moieties on MUC to enhance infection [69]. Although the precise biological mechanism of how this binding propensity enhances infection is incompletely understood for TMEV, there are several possible explanations beyond receptor binding and entry. For example, MUC‐bound virus could be protected from inactivation in a low‐pH environment, as well as from host digestive enzymes. Alternatively, binding to mucus may promote longer retention of the virus in the gut, thereby enabling the virus to become peristalsis‐resistant [69]. A third possibility is that the sialic acid‐binding sites on TMEV correspond to neutralizing antibody sites [69], which could help the virus evade host immunity.

It is intriguing to consider whether these proviral mechanisms are more broadly applicable to other enteric viruses. A recent study noted that recovery of norovirus, rotavirus, astrovirus, sapovirus, and husavirus from sewage was enhanced by a pig‐MUC capture method [70]. In separate studies, MUC has been shown to promote poliovirus infectivity [71], to enhance the thermostability of reovirus [72], and to stabilize human astrovirus serotype 1 capsid and thereby preserve the infectivity of the virus during heat treatment [73]. Given that changes in mucus production can also cause changes in microbiome composition, it is also possible that virus–bacteria interactions play a role in these proviral mechanisms, as was noted in previous comprehensive reviews [74, 75].

In contrast to these benefits derived by the virus from MUC binding, there is also evidence that MUC can serve as a ‘trap’ for virus particles, in much the same way that it traps bacteria and parasites [1]. In multiple studies, sialic acid‐dependent strains of rotavirus exhibited reduced infectivity when co‐incubated with mucus [62, 76, 77, 78, 79], whereas deglycosylation or neuraminidase (NA) treatment to remove sialic acid moieties from mucus abrogated this effect and enabled cells to be infected [76, 77, 79]. An increase in mucolytic bacteria has also been shown to aid rotavirus in its effect to subvert mucus interference, again highlighting an important multimicrobe interaction [80]. Reovirus can also combat mucus via its σ1 protein, which exhibits glycosidase activity and, therefore, could be important for mucus penetration [81]. In short, MUC appears to serve as a ‘double‐edged’ sword that viruses may combat or co‐opt during infection (Fig. 2).

Beyond these cellular functions related to mucus barrier maintenance, goblet cells also play a critical role in the development of oral tolerance, with mucus driving tolerogenic effects via crosstalk with immune cells [82, 83]. Therefore, it is intriguing to consider whether virus association with mucus could serve as an immune evasion strategy or whether viral infection of goblet cells could trigger the formation of goblet cell‐associated antigen passages [84], which enable luminal contents to be sampled by the underlying antigen‐presenting cells in the lamina propria. Is it possible that enteric viruses, in a similar manner to Salmonella enteric serovar Typhimurium [85], use goblet cell‐associated antigen passages to mediate extra‐gastrointestinal spread? In addition, S. Typhimurium is known to colonize the mouse cecum due to exposure of the epithelium in areas without a thick mucus barrier [86], which could also benefit viruses that are greatly impeded by mucus. Similarly, the overlaying mucus on the epithelial layer of Peyer’s patches is known to be much thinner than the surrounding epithelium [27], indicating that viruses that gain entry or infect these sites, such as murine norovirus via microfold cells [87], may also play a role. The extent to which this and other functions of goblet cells in the gut contribute to protection against or the pathogenesis of viral infections is an exciting new avenue of research waiting to be explored.

Airway goblet cells

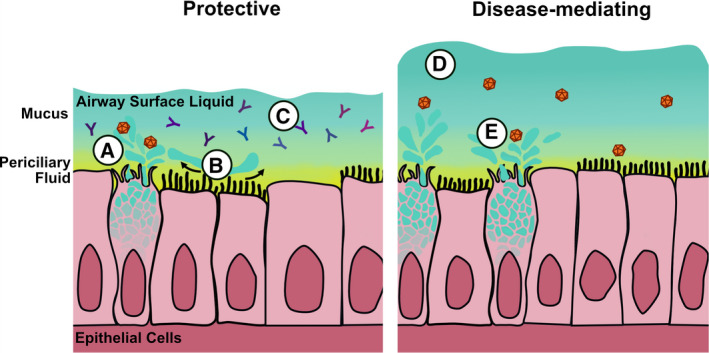

Distinct from the intestinal epithelium, the lung airways are lined by a pseudostratified epithelial layer that consists of basal and club progenitor cells that differentiate into ciliated and secretory cell types, including goblet cells [15, 88]. The mucus barrier in the airways comprises the periciliary fluid and airway liquid surface layers (Fig. 3). In mice, the airway liquid surface layer is 10–30 µm thick whereas in humans, the periciliary fluid is ~ 4–7 µm and the top mucus layer is highly variable, ranging from 10 to 70 µm in depending on the section of the airway [89, 90, 91, 92, 93]. Together with ciliated cells that display motile cilia on their apical surface, mucus secretion from goblet cells and submucosal gland cells is critical for mediating mucociliary clearance, which sweeps inhaled debris and potential pathogens out of the airways [94]. Although the airways harbor 14 distinct MUC that support the mucus layers, the primary secreted MUC that are analogous to MUC2 in the intestinal tract are MUC5B and MUC5AC [15].

Fig 3.

Goblet cells that line the airways are critical to maintaining homeostatic conditions that serve as protection against viral infection (shown at left). A) Mucus can bind the virus and sequester it from the epithelial layer. B) Mucus secretion aids mucociliary clearance of virus particles. C) Mucus‐associated antibody can also help to block viral infection. D) Goblet cell‐driven airway disease can be caused by overexuberant mucus responses (shown at right), leading to impaired mucociliary clearance. E) Some viruses can benefit from MUC interactions to help enhance their stability, infection, and transmission.

Respiratory viruses in goblet cells

In contrast to intestinal goblet cells, much has been uncovered about airway goblet cell interactions with viruses, particularly with respect to mucus binding (Fig. 3). Goblet cells are the direct targets of many human respiratory viruses, such as hantavirus [95], rhinovirus [96], and multiple influenza viruses, including influenza A viruses H1N1, H5N1, H7N9, H5N6, and H3N2, as well as influenza B virus [97, 98, 99]. Influenza virus is probably the most studied respiratory virus with direct MUC interactions: its hemagglutinin (HA) surface protein binds to epithelial sialic acid to mediate cell entry. Thus, mucus binding by influenza viruses is in part a side effect of their receptor usage, but mucus has been shown to both aid and hinder infection, with evidence of host‐variable distinctions [100]. Previous studies demonstrated that MUC5AC overexpression in transgenic mice reduced H1N1 virus titers in the lung, which coincided with reduced immune cell infiltration [101]. Cell surface MUC can also serve as decoy receptors for influenza [102, 103], and Muc1‐deficient mice exhibit more severe H1N1 virus infection [102], highlighting the important role that MUC can play in antiviral defense. However, because influenza virus also displays a NA protein on its virion surface, it can mitigate these mucus effects. Indeed, NA is important for virus release when HA molecules tether nascent virus particles to the cell surface [104, 105] and also for viral entry, in which it combats mucus hindrance [106, 107, 108, 109]. Studies have shown that influenza virus can even co‐opt mucus binding as a means of traversing the mucus barrier to find its cellular receptor [110, 111, 112]. Therefore, a careful balance between HA and NA expression on the virus surface is key to optimal infection [113], and virus interactions with mucus have been shown to have a significant impact on transmission [114, 115] and on cross‐species restriction [116].

Much like in the gut, basal mucus production in the lung is intended to flush out pathogens and other irritants in the airways. However, this important host response can become exaggerated to the point where it contributes to acute respiratory distress syndrome (Fig. 3). Most recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) was shown to infect goblet cells in human bronchial explants and was also identified by postmortem analysis [117, 118], but such infection was not observed in 2‐D airway organoid cultures [119], perhaps reflecting differences in the detection methodology. Interestingly, SARS‐CoV‐1 infection was not shown to target goblet cells in vitro or in vivo [119, 120, 121], whereas canine respiratory coronavirus, a related betacoronavirus, has been shown to infect goblet cells in canine tracheal cultures [122]. Even if goblet cells are not frequently infected by SARS‐CoV‐2, investigation of their role in mediating airway disease is warranted, as clinical reports have commonly identified mucus accumulation in fatal cases of COVID [123, 124, 125] and because several other viral infections drive goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus metaplasia, leading to compromised lung function. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a textbook example of this and is by far the most prevalent cause of lower respiratory disease in infants and young children [126]. Without directly infecting goblet cells, RSV induces goblet cell hyperplasia and hypersecretion via the induction of Th2 cytokines [127], but IL‐4 receptor antagonism can block these cytokine signals and has been effective in vivo [128]. It was also shown that IL‐12p40, which generally functions as a brake on Th2 hyper‐responsiveness, is critical for controlling disease caused by RSV as well as that caused by human metapneumovirus, a related pneumovirus [129, 130]. Rhinoviruses, which are responsible for the common cold, similarly drive an increase in MUC production in vitro and in vivo [131, 132, 133], and although this has been shown to be protective against infection [134], it can cause complications in the event that the mucus response becomes excessive. Drug treatments, including those with anticholinergic agents, corticosteroids, and anti‐inflammatory drugs, have proved effective at mitigating overexuberant goblet cell responses caused by rhinovirus and RSV in vitro and in vivo [135, 136]. However, it is important to note that these interventions can come at a cost to antiviral immune responses and may result in reduced viral clearance [137]. Therefore, additional study of goblet cell functions could aid the design of appropriate interventions to mitigate aberrant host responses and promote antiviral responses that will improve respiratory virus disease outcomes.

Concluding remarks

Armed with MUC and other antimicrobial proteins that offer structural and functional interactions with microbes and host immune cells, goblet cells provide a critical link in the innate immune responses in the airways and intestines. We are only beginning to scratch the surface of the heterogeneity within goblet cell populations but improving our understanding of how goblet cell responses are shaped by host, microbe, and viral factors will be critical to developing strategies that modulate their activity. Ultimately, understanding their basic biology will help to improve host susceptibility and disease outcomes to enteric and respiratory viral infections.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

VC and SS‐C came up with the idea of reviewing this topic. VC wrote the manuscript. VC and SS‐C edited this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rebekah Honce for graphical design of the figures and Keith A. Laycock, PhD, ELS, for scientific editing of the manuscript. Funding for this research included National Institutes of Health Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R21 AI135254‐01 and R03 AI126101‐01 to SS‐C and T32 AI106700‐03 to VC, as well as funding from ALSAC to SS‐C.

References

- 1. Kim JJ & Khan WI (2013) Goblet cells and mucins: role in innate defense in enteric infections. Pathogens 2, 55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pelaseyed T, Bergström JH, Gustafsson JK, Ermund A, Birchenough GMH, Schütte A, van der Post S, Svensson F, Rodríguez‐Piñeiro AM, Nyström EEL et al. (2014) The mucus and mucins of the goblet cells and enterocytes provide the first defense line of the gastrointestinal tract and interact with the immune system. Immunol Rev 260, 8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Birchenough GMH, Johansson MEV, Gustafsson JK, Bergström JH & Hansson GC (2015) New developments in goblet cell mucus secretion and function. Mucosal Immunol 8, 712–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allaire JM, Morampudi V, Crowley SM, Stahl M, Yu H, Bhullar K, Knodler LA, Bressler B, Jacobson K & Vallance BA (2018) Frontline defenders: goblet cell mediators dictate host‐microbe interactions in the intestinal tract during health and disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 314, G360–G377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies JM & Abreu MT (2015) Host‐microbe interactions in the small bowel. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 31, 118–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergström A, Kristensen MB, Bahl MI, Metzdorff SB, Fink LN, Frøkiær H & Licht TR (2012) Nature of bacterial colonization influences transcription of mucin genes in mice during the first week of life. BMC Res Notes 5, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wlodarska M, Willing B, Keeney KM, Menendez A, Bergstrom KS, Gill N, Russell SL, Vallance BA & Finlay BB (2011) Antibiotic treatment alters the colonic mucus layer and predisposes the host to exacerbated Citrobacter rodentium‐induced colitis. Infect Immun 79, 1536–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen C‐Y, Hsu K‐C, Yeh H‐Y & Ho H‐C (2019) Visualizing the effects of antibiotics on the mouse colonic mucus layer. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi 32, 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birchenough GMH, Nyström EEL, Johansson MEV & Hansson GC (2016) A sentinel goblet cell guards the colonic crypt by triggering Nlrp6‐dependent Muc2 secretion. Science 352, 1535–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Becker S, Oelschlaeger TA, Wullaert A, Pasparakis M, Wehkamp J, Stange EF & Gersemann M (2013) Bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial cell differentiation factors both in vitro and in vivo . PLoS One 8, e55620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schütte A, Ermund A, Becker‐Pauly C, Johansson MEV, Rodriguez‐Pineiro AM, Bäckhed F, Müller S, Lottaz D, Bond JS & Hansson GC (2014) Microbial‐induced meprin β cleavage in MUC2 mucin and a functional CFTR channel are required to release anchored small intestinal mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 12396–12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chapter IV (1968) The goblet cell in general. Acta Ophthalmol 46, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13. VanDussen KL & Samuelson LC (2010) Mouse atonal homolog 1 directs intestinal progenitors to secretory cell rather than absorptive cell fate. Dev Biol 346, 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noah TK, Kazanjian A, Whitsett J & Shroyer NF (2010) SAM pointed domain ETS factor (SPDEF) regulates terminal differentiation and maturation of intestinal goblet cells. Exp Cell Res 316, 452–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whitsett JA (2018) Airway epithelial differentiation and mucociliary clearance. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15, S143–S148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Xu Y, Kitzmiller J, Wert SE, Maeda Y, Gregorieff A, Clevers H & Whitsett JA (2009) SPDEF is required for mouse pulmonary goblet cell differentiation and regulates a network of genes associated with mucus production. J Clin Invest 119, 2914–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rajavelu P, Chen G, Xu Y, Kitzmiller JA, Korfhagen TR & Whitsett JA (2015) Airway epithelial SPDEF integrates goblet cell differentiation and pulmonary Th2 inflammation. J Clin Invest 125, 2021–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Specian RD & Neutra MR (1982) Regulation of intestinal goblet cell secretion. I. Role of parasympathetic stimulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 242, G370–G379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johansson MEV (2012) Fast renewal of the distal colonic mucus layers by the surface goblet cells as measured by in vivo labeling of mucin glycoproteins. PLoS One 7, e41009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis CW & Dickey BF (2008) Regulated airway goblet cell mucin secretion. Annu Rev Physiol 70, 487–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wlodarska M, Thaiss CA, Nowarski R, Henao‐Mejia J, Zhang J‐P, Brown EM, Frankel G, Levy M, Katz MN, Philbrick WM et al. (2014) NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host‐microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell 156, 1045–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patel KK, Miyoshi H, Beatty WL, Head RD, Malvin NP, Cadwell K, Guan J‐L, Saitoh T, Akira S, Seglen PO et al. (2013) Autophagy proteins control goblet cell function by potentiating reactive oxygen species production. EMBO J 32, 3130–3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu Y, Tang L, Wang B, Sun Q, Zhao P & Li W (2019) The role of autophagy in maintaining intestinal mucosal barrier. J Cell Physiol 234, 19406–19419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ranson N, Veldhuis M, Mitchell B, Fanning S, Cook AL, Kunde D & Eri R (2018) Nod‐like receptor pyrin‐containing protein 6 (NLRP6) is up‐regulated in ileal Crohn’s disease and differentially expressed in goblet cells. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 6, 110–112.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gremel G, Wanders A, Cedernaes J, Fagerberg L, Hallström B, Edlund K, Sjöstedt E, Uhlén M & Pontén F (2015) The human gastrointestinal tract‐specific transcriptome and proteome as defined by RNA sequencing and antibody‐based profiling. J Gastroenterol 50, 46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gustafsson JK, Ermund A, Johansson MEV, Schütte A, Hansson GC & Sjövall H (2011) An ex vivo method for studying mucus formation, properties, and thickness in human colonic biopsies and mouse small and large intestinal explants. Am J Physiol 302, G430–G438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ermund A, Schütte A, Johansson MEV, Gustafsson JK & Hansson GC (2013) Studies of mucus in mouse stomach, small intestine, and colon. I. Gastrointestinal mucus layers have different properties depending on location as well as over the Peyer’s patches. Am J Physiol 305, G341–G347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halm DR & Halm ST (2000) Secretagogue response of goblet cells and columnar cells in human colonic crypts1. Am J Physiol 278, C212–C233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Linden SK, Sutton P, Karlsson NG, Korolik V & McGuckin MA (2008) Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol 1, 183–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohn L, Homer RJ, MacLeod H, Mohrs M, Brombacher F & Bottomly K (1999) Th2‐induced airway mucus production is dependent on IL‐4Rα, but not on eosinophils. J Immunol 162, 6178–6183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharba S, Navabi N, Padra M, Persson JA, Quintana‐Hayashi MP, Gustafsson JK, Szeponik L, Venkatakrishnan V, Sjöling Å, Nilsson S et al. (2019) Interleukin 4 induces rapid mucin transport, increases mucus thickness and quality and decreases colitis and Citrobacter rodentium in contact with epithelial cells. Virulence 10, 97–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wynn TA (2003) IL‐13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol 21, 425–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johansson MEV, Jakobsson HE, Holmén‐Larsson J, Schütte A, Ermund A, Rodríguez‐Piñeiro AM, Arike L, Wising C, Svensson F, Bäckhed F et al. (2015) Normalization of host intestinal mucus layers requires long‐term microbial colonization. Cell Host Microbe 18, 582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paone P & Cani PD (2020) Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut 69, 2232–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johansson MEV, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L & Hansson GC (2008) The inner of the two Muc2 mucin‐dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 15064–15069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johansson MEV, Gustafsson JK, Holmén‐Larsson J, Jabbar KS, Xia L, Xu H, Ghishan FK, Carvalho FA, Gewirtz AT, Sjövall H et al. (2014) Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 63, 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pullan RD, Thomas GA, Rhodes M, Newcombe RG, Williams GT, Allen A & Rhodes J (1994) Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis. Gut 35, 353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fyderek K, Strus M, Kowalska‐Duplaga K, Gosiewski T, Wedrychowicz A, Jedynak‐Wasowicz U, Sładek M, Pieczarkowski S, Adamski P, Kochan P et al. (2009) Mucosal bacterial microflora and mucus layer thickness in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 15, 5287–5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sontheimer‐Phelps A, Chou DB, Tovaglieri A, Ferrante TC, Duckworth T, Fadel C, Frismantas V, Sutherland AD, Jalili‐Firoozinezhad S, Kasendra M et al. (2020) Human colon‐on‐a‐chip enables continuous in vitro analysis of colon mucus layer accumulation and physiology. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 9, 507–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Graf K, Last A, Gratz R, Allert S, Linde S, Westermann M, Gröger M, Mosig AS, Gresnigt MS & Hube B (2019) Keeping Candida commensal: how lactobacilli antagonize pathogenicity of Candida albicans in an in vitro gut model. Dis Model Mech 12, dmm039719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nyström EEL, Birchenough GMH, van der Post S, Arike L, Gruber AD, Hansson GC & Johansson MEV (2018) Calcium‐activated Chloride Channel Regulator 1 (CLCA1) controls mucus expansion in colon by proteolytic activity. EBioMedicine 33, 134–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nyström EEL, Arike L, Ehrencrona E, Hansson GC & Johansson MEV (2019) Calcium‐activated chloride channel regulator 1 (CLCA1) forms non‐covalent oligomers in colonic mucus and has mucin 2‐processing properties. J Biol Chem 294, 17075–17089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Johansson MEV, Thomsson KA & Hansson GC (2009) Proteomic analyses of the two mucus layers of the colon barrier reveal that their main component, the Muc2 mucin, is strongly bound to the Fcgbp protein. J Proteome Res 8, 3549–3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bergström JH, Berg KA, Rodríguez‐Piñeiro AM, Stecher B, Johansson MEV & Hansson GC (2014) AGR2, an endoplasmic reticulum protein, is secreted into the gastrointestinal mucus. PLoS One 9, e104186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bergström JH, Birchenough GMH, Katona G, Schroeder BO, Schütte A, Ermund A, Johansson MEV & Hansson GC (2016) Gram‐positive bacteria are held at a distance in the colon mucus by the lectin‐like protein ZG16. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113, 13833–13838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Taupin D & Podolsky DK (2003) Trefoil factors: initiators of mucosal healing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4, 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holly MK & Smith JG (2018) Paneth cells during viral infection and pathogenesis. Viruses 10, 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kaetzel CS (2014) Cooperativity among secretory IgA, the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, and the gut microbiota promotes host‐microbial mutualism. Immunol Lett 162, 10–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Blutt SE & Conner ME (2013) The gastrointestinal frontier: IgA and viruses. Front Immunol 4, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suzuki H & Konno T (1975) Reovirus‐like particles in jejunal mucosa of a Japanese infant with acute infectious non‐bacterial gastroenteritis. Tohoku J Exp Med 115, 199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takeuchi A & Hashimoto K (1976) Electron microscope study of experimental enteric adenovirus infection in mice. Infect Immun 13, 569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Doughri AM & Storz J (1977) Light and ultrastructural pathologic changes in intestinal coronavirus infection of newborn calves. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B 24, 367–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lanik WE, Mara MA, Mihi B, Coyne CB & Good M (2018) Stem cell‐derived models of viral infections in the gastrointestinal tract. Viruses 10, 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li L, Fu F, Guo S, Wang H, He X, Xue M, Yin L, Feng L & Liu P (2019) Porcine intestinal enteroids: a new model for studying enteric coronavirus porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection and the host innate response. J Virol 93, e01682‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Holly MK & Smith JG (2018) Adenovirus infection of human enteroids reveals interferon sensitivity and preferential infection of goblet cells. J Virol 92, e00250‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Good C, Wells AI & Coyne CB (2019) Type III interferon signaling restricts enterovirus 71 infection of goblet cells. Sci Adv 5, eaau4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kolawole AO, Mirabelli C, Hill DR, Svoboda SA, Janowski AB, Passalacqua KD, Rodriguez BN, Dame MK, Freiden P, Berger RP et al. (2019) Astrovirus replication in human intestinal enteroids reveals multi‐cellular tropism and an intricate host innate immune landscape. PLoS Pathog 15, e1008057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cortez V, Boyd DF, Crawford JC, Sharp B, Livingston B, Rowe HM, Davis A, Alsallaq R, Robinson CG, Vogel P et al. (2020) Astrovirus infects actively secreting goblet cells and alters the gut mucus barrier. Nat Commun 11, 2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moncada DM, Kammanadiminti SJ & Chadee K (2003) Mucin and Toll‐like receptors in host defense against intestinal parasites. Trends Parasitol 19, 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kim YS & Ho SB (2010) Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 12, 319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jung K & Saif LJ (2017) Goblet cell depletion in small intestinal villous and crypt epithelium of conventional nursing and weaned pigs infected with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Res Vet Sci 110, 12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Boshuizen JA, Reimerink JHJ, Korteland‐van Male AM, van Ham VJJ, Bouma J, Gerwig GJ, Koopmans MPG, Büller HA, Dekker J & Einerhand AWC (2005) Homeostasis and function of goblet cells during rotavirus infection in mice. Virology 337, 210–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wu A, Yu B, Zhang K, Xu Z, Wu D, He J, Luo J, Luo Y, Yu J, Zheng P et al. (2020) Transmissible gastroenteritis virus targets Paneth cells to inhibit the self‐renewal and differentiation of Lgr5 intestinal stem cells via Notch signaling. Cell Death Dis 11, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Xia L, Dai L, Yu Q & Yang Q (2017) Persistent transmissible gastroenteritis virus infection enhances enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 adhesion by promoting epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in intestinal epithelial cells. J Virol 91, e01256‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cornick S, Tawiah A & Chadee K (2015) Roles and regulation of the mucus barrier in the gut. Tissue Barriers 3, e982426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sicard J‐F, Le Bihan G, Vogeleer P, Jacques M & Harel J (2017) Interactions of intestinal bacteria with components of the intestinal mucus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7, 387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schwegmann‐Wessels C, Zimmer G, Schröder B, Breves G & Herrler G (2003) Binding of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus to brush border membrane sialoglycoproteins. J Virol 77, 11846–11848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schwegmann‐Wessels C, Bauer S, Winter C, Enjuanes L, Laude H & Herrler G (2011) The sialic acid binding activity of the S protein facilitates infection by porcine transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. Virol J 8, 435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tsunoda I, Libbey JE & Fujinami RS (2009) Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus attachment to the gastrointestinal tract is associated with sialic acid binding. J Neurovirol 15, 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Strubbia S, Phan MVT, Schaeffer J, Koopmans M, Cotten M & Le Guyader FS (2019) Characterization of norovirus and other human enteric viruses in sewage and stool samples through next‐generation sequencing. Food Environ Virol 11, 400–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kuss SK, Best GT, Etheredge CA, Pruijssers AJ, Frierson JM, Hooper LV, Dermody TS & Pfeiffer JK (2011) Intestinal microbiota promote enteric virus replication and systemic pathogenesis. Science 334, 249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Berger AK, Yi H, Kearns DB & Mainou BA (2017) Bacteria and bacterial envelope components enhance mammalian reovirus thermostability. PLoS Pathog 13, e1006768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pérez‐Rodriguez FJ, Vieille G, Turin L, Yildiz S, Tapparel C & Kaiser L (2019) Fecal components modulate human astrovirus infectivity in cells and reconstituted intestinal tissues. mSphere 4, e00568‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pfeiffer JK & Virgin HW (2016) Viral immunity. Transkingdom control of viral infection and immunity in the mammalian intestine. Science 351, aad5872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Karst SM (2016) The influence of commensal bacteria on infection with enteric viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chen CC, Baylor M & Bass DM (1993) Murine intestinal mucins inhibit rotavirus infection. Gastroenterology 105, 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Willoughby RE & Yolken RH (1990) SA11 rotavirus is specifically inhibited by an acetylated sialic acid. J Infect Dis 161, 116–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yolken RH, Willoughby R, Wee SB, Miskuff R & Vonderfecht S (1987) Sialic acid glycoproteins inhibit in vitro and in vivo replication of rotaviruses. J Clin Invest 79, 148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yolken RH, Ojeh C, Khatri IA, Sajjan U & Forstner JF (1994) Intestinal mucins inhibit rotavirus replication in an oligosaccharide‐dependent manner. J Infect Dis 169, 1002–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Engevik MA, Banks LD, Engevik KA, Chang‐Graham AL, Perry JL, Hutchinson DS, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF & Hyser JM (2020) Rotavirus infection induces glycan availability to promote ileum‐specific changes in the microbiome aiding rotavirus virulence. Gut Microbes 11, 1324–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bisaillon M, Sénéchal S, Bernier L & Lemay G (1999) A glycosyl hydrolase activity of mammalian reovirus sigma1 protein can contribute to viral infection through a mucus layer. J Mol Biol 286, 759–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kulkarni DH, Gustafsson JK, Knoop KA, McDonald KG, Bidani SS, Davis JE, Floyd AN, Hogan SP, Hsieh C‐S & Newberry RD (2019) Goblet cell associated antigen passages support the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance. Mucosal Immunol 13, 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shan M, Gentile M, Yeiser JR, Walland AC, Bornstein VU, Chen K, He B, Cassis L, Bigas A, Cols M et al. (2013) Mucus enhances gut homeostasis and oral tolerance by delivering immunoregulatory signals. Science 342, 447–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. McDole JR, Wheeler LW, McDonald KG, Wang B, Konjufca V, Knoop KA, Newberry RD & Miller MJ (2012) Goblet cells deliver luminal antigen to CD103+ dendritic cells in the small intestine. Nature 483, 345–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kulkarni DH, McDonald KG, Knoop KA, Gustafsson JK, Kozlowski KM, Hunstad DA, Miller MJ & Newberry RD (2018) Goblet cell associated antigen passages are inhibited during Salmonella typhimurium infection to prevent pathogen dissemination and limit responses to dietary antigens. Mucosal Immunol 11, 1103–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Furter M, Sellin ME, Hansson GC & Hardt W‐D (2019) Mucus architecture and near‐surface swimming affect distinct Salmonella typhimurium infection patterns along the murine intestinal tract. Cell Rep 27, 2665–2678.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kolawole AO, Gonzalez‐Hernandez MB, Turula H, Yu C, Elftman MD & Wobus CE (2016) Oral norovirus infection is blocked in mice lacking Peyer’s patches and mature M cells. J Virol 90, 1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zaragosi LE, Deprez M & Barbry P (2020) Using single‐cell RNA sequencing to unravel cell lineage relationships in the respiratory tract. Biochem Soc Trans 48, 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Atanasova KR & Reznikov LR (2019) Strategies for measuring airway mucus and mucins. Respir Res 20, 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Fahy JV & Dickey BF (2010) Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med 363, 2233–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Morgan KS, Donnelley M, Paganin DM, Fouras A, Yagi N, Suzuki Y, Takeuchi A, Uesugi K, Boucher RC, Parsons DW et al. (2013) Measuring airway surface liquid depth in ex vivo mouse airways by x‐ray imaging for the assessment of cystic fibrosis airway therapies. PLoS One 8, e55822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Matsui H, Grubb BR, Tarran R, Randell SH, Gatzy JT, Davis CW & Boucher RC (1998) Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell 95, 1005–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Derichs N, Jin B‐J, Song Y, Finkbeiner WE & Verkman AS (2011) Hyperviscous airway periciliary and mucous liquid layers in cystic fibrosis measured by confocal fluorescence photobleaching. FASEB J 25, 2325–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Benam KH, Vladar EK, Janssen WJ & Evans CM (2018) Mucociliary defense: emerging cellular, molecular, and animal models. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15, S210–S215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Rowe RK & Pekosz A (2006) Bidirectional virus secretion and nonciliated cell tropism following Andes virus infection of primary airway epithelial cell cultures. J Virol 80, 1087–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Lachowicz‐Scroggins ME, Boushey HA, Finkbeiner WE & Widdicombe JH (2010) Interleukin‐13‐induced mucous metaplasia increases susceptibility of human airway epithelium to rhinovirus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43, 652–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Essaidi‐Laziosi M, Brito F, Benaoudia S, Royston L, Cagno V, Fernandes‐Rocha M, Piuz I, Zdobnov E, Huang S, Constant S et al. (2018) Propagation of respiratory viruses in human airway epithelia reveals persistent virus‐specific signatures. J Allergy Clin Immunol 141, 2074–2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hui KPY, Ching RHH, Chan SKH, Nicholls JM, Sachs N, Clevers H, Peiris JSM & Chan MCW (2018) Tropism, replication competence, and innate immune responses of influenza virus: an analysis of human airway organoids and ex‐vivo bronchus cultures. Lancet Respir Med 6, 846–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zeng H, Goldsmith CS, Kumar A, Belser JA, Sun X, Pappas C, Brock N, Bai Y, Levine M, Tumpey TM et al. (2019) Tropism and Infectivity of a Seasonal A(H1N1) and a Highly Pathogenic Avian A(H5N1) influenza virus in primary differentiated ferret nasal epithelial cell cultures. J Virol 93, e00080‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Barnard KN, Alford‐Lawrence BK, Buchholz DW, Wasik BR, LaClair JR, Yu H, Honce R, Ruhl S, Pajic P, Daugherity EK et al. (2020) Modified sialic acids on mucus and erythrocytes inhibit influenza a virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase functions. J Virol 94, e01567‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ehre C, Worthington EN, Liesman RM, Grubb BR, Barbier D, O’Neal WK, Sallenave J‐M, Pickles RJ & Boucher RC (2012) Overexpressing mouse model demonstrates the protective role of Muc5ac in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 16528–16533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. McAuley JL, Corcilius L, Tan H‐X, Payne RJ, McGuckin MA & Brown LE (2017) The cell surface mucin MUC1 limits the severity of influenza A virus infection. Mucosal Immunol 10, 1581–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Delaveris CS, Webster ER, Banik SM, Boxer SG & Bertozzi CR (2020) Membrane‐tethered mucin‐like polypeptides sterically inhibit binding and slow fusion kinetics of influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 12643–12650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Palese P, Tobita K, Ueda M & Compans RW (1974) Characterization of temperature sensitive influenza virus mutants defective in neuraminidase. Virology 61, 397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Basak S, Tomana M & Compans RW (1985) Sialic acid is incorporated into influenza hemagglutinin glycoproteins in the absence of viral neuraminidase. Virus Res 2, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Cohen M, Zhang X‐Q, Senaati HP, Chen H‐W, Varki NM, Schooley RT & Gagneux P (2013) Influenza A penetrates host mucus by cleaving sialic acids with neuraminidase. Virol J 10, 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Matrosovich MN, Matrosovich TY, Gray T, Roberts NA & Klenk H‐D (2004) Neuraminidase is important for the initiation of influenza virus infection in human airway epithelium. J Virol 78, 12665–12667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ohuchi M, Asaoka N, Sakai T & Ohuchi R (2006) Roles of neuraminidase in the initial stage of influenza virus infection. Microbes Infect 8, 1287–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Yang X, Steukers L, Forier K, Xiong R, Braeckmans K, Reeth KV & Nauwynck H (2014) A beneficiary role for neuraminidase in influenza virus penetration through the respiratory mucus. PLoS One 9, e110026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Vahey MD & Fletcher DA (2019) Influenza A virus surface proteins are organized to help penetrate host mucus. eLife 8, e43764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Guo H, Rabouw H, Slomp A, Dai M, van der Vegt F, van Lent JWM, McBride R, Paulson JC, de Groot RJ, van Kuppeveld FJM et al. (2018) Kinetic analysis of the influenza A virus HA/NA balance reveals contribution of NA to virus‐receptor binding and NA‐dependent rolling on receptor‐containing surfaces. PLOS Pathog 14, e1007233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Sakai T, Nishimura SI, Naito T & Saito M (2017) Influenza A virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase act as novel motile machinery. Sci Rep 7, 45043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. de Vries E, Du W, Guo H & de Haan CAM (2020) Influenza A virus hemagglutinin–neuraminidase–receptor balance: preserving virus motility. Trends Microbiol 28, 57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Yen H‐L, Liang C‐H, Wu C‐Y, Forrest HL, Ferguson A, Choy K‐T, Jones J, Wong DD‐Y, Cheung PP‐H, Hsu C‐H et al. (2011) Hemagglutinin‐neuraminidase balance confers respiratory‐droplet transmissibility of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in ferrets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 14264–14269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. van Riel D, den Bakker MA, Leijten LME, Chutinimitkul S, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RAM, Osterhaus ADME & Kuiken T (2010) Seasonal and pandemic human influenza viruses attach better to human upper respiratory tract epithelium than avian influenza viruses. Am J Pathol 176, 1614–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Zanin M, Marathe B, Wong S‐S, Yoon S‐W, Collin E, Oshansky C, Jones J, Hause B & Webby R (2015) Pandemic swine H1N1 influenza viruses with almost undetectable neuraminidase activity are not transmitted via aerosols in ferrets and are inhibited by human mucus but not swine mucus. J Virol 89, 5935–5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Hui KPY, Cheung M‐C, Perera RAPM, Ng K‐C, Bui CHT, Ho JCW, Ng MMT, Kuok DIT, Shih KC, Tsao S‐W et al. (2020) Tropism, replication competence, and innate immune responses of the coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 in human respiratory tract and conjunctiva: an analysis in ex‐vivo and in‐vitro cultures. Lancet Respir Med 8, 687–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Schaefer I‐M, Padera RF, Solomon IH, Kanjilal S, Hammer MM, Hornick JL & Sholl LM (2020) In situ detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 in lungs and airways of patients with COVID‐19. Modern Pathol 33, 2104–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Lamers MM, Beumer J, van der Vaart J, Knoops K, Puschhof J, Breugem TI, Ravelli RBG, Paul van Schayck J, Mykytyn AZ, Duimel HQ et al. (2020) SARS‐CoV‐2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science 369, 50–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. van den Brand JMA, Haagmans BL, Leijten L, van Riel D, Martina BEE, Osterhaus ADME & Kuiken T (2008) Pathology of experimental SARS coronavirus infection in cats and ferrets. Vet Pathol 45, 551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Shieh W‐J, Hsiao C‐H, Paddock CD, Guarner J, Goldsmith CS, Tatti K, Packard M, Mueller L, Wu M‐Z, Rollin P et al. (2005) Immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization, and ultrastructural localization of SARS‐associated coronavirus in lung of a fatal case of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Taiwan. Hum Pathol 36, 303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Priestnall SL, Mitchell JA, Brooks HW, Brownlie J & Erles K (2009) Quantification of mRNA encoding cytokines and chemokines and assessment of ciliary function in canine tracheal epithelium during infection with canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV). Vet Immunol Immunopathol 127, 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, Rossi RS, Pellegrinelli A, Zerbi P, Rech R, Colombo R, Antinori S, Corbellino M et al. (2020) Pulmonary post‐mortem findings in a series of COVID‐19 cases from northern Italy: a two‐centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 20, 1135–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Farooqi FI, Morgan RC, Dhawan N, Dinh J, Yatzkan G & Michel G (2020) Airway hygiene in COVID‐19 pneumonia: treatment responses of 3 critically Ill cruise ship employees. Am J Case Rep 21, e926596‐1‐e926596‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Menter T, Haslbauer JD, Nienhold R, Savic S, Hopfer H, Deigendesch N, Frank S, Turek D, Willi N, Pargger H et al. (2020) Postmortem examination of COVID‐19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings in lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology 77, 198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, Simoes EAF, Madhi SA, Gessner BD, Polack FP, Balsells E, Acacio S, Aguayo C et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet 390, 946–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Carvajal JJ, Avellaneda AM, Salazar‐Ardiles C, Maya JE, Kalergis AM & Lay MK (2019) Host components contributing to respiratory syncytial virus pathogenesis. Front Immunol 10, 2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ripple MJ, You D, Honnegowda S, Giaimo JD, Sewell AB, Becnel DM & Cormier SA (2010) Immunomodulation with IL‐4R alpha antisense oligonucleotide prevents respiratory syncytial virus‐mediated pulmonary disease. J Immunol 185, 4804–4811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Chakraborty K, Zhou Z, Wakamatsu N & Guerrero‐Plata A (2012) Interleukin‐12p40 modulates human metapneumovirus‐induced pulmonary disease in an acute mouse model of infection. PLoS One 7, e37173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Wang S‐Z, Bao Y‐X, Rosenberger CL, Tesfaigzi Y, Stark JM & Harrod KS (2004) IL‐12p40 and IL‐18 modulate inflammatory and immune responses to respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol 173, 4040–4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Inoue D, Yamaya M, Kubo H, Sasaki T, Hosoda M, Numasaki M, Tomioka Y, Yasuda H, Sekizawa K, Nishimura H et al. (2006) Mechanisms of mucin production by rhinovirus infection in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Respi Physiol Neurobiol 154, 484–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Yuta A, Doyle WJ, Gaumond E, Ali M, Tamarkin L, Baraniuk JN, Van Deusen M, Cohen S & Skoner DP (1998) Rhinovirus infection induces mucus hypersecretion. Am J Physiol 274, L1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Hewson CA, Haas JJ, Bartlett NW, Message SD, Laza‐Stanca V, Kebadze T, Caramori G, Zhu J, Edbrooke MR, Stanciu LA et al. (2010) Rhinovirus induces MUC5AC in a human infection model and in vitro via NF‐κB and EGFR pathways. Eur Respir J 36, 1425–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Jakiela B, Gielicz A, Plutecka H, Hubalewska‐Mazgaj M, Mastalerz L, Bochenek G, Soja J, Januszek R, Aab A, Musial J et al. (2014) Th2‐type cytokine‐induced mucus metaplasia decreases susceptibility of human bronchial epithelium to rhinovirus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 51, 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Wang Y, Ninaber DK, van Schadewijk A & Hiemstra PS (2020) Tiotropium and fluticasone inhibit rhinovirus‐induced mucin production via multiple mechanisms in differentiated airway epithelial cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10, 278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Mata M, Martinez I, Melero JA, Tenor H & Cortijo J (2013) Roflumilast inhibits respiratory syncytial virus infection in human differentiated bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One 8, e69670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Singanayagam A, Glanville N, Bartlett N & Johnston S (2015) Effect of fluticasone propionate on virus‐induced airways inflammation and anti‐viral immune responses in mice. Lancet 385 (Suppl 1), S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]