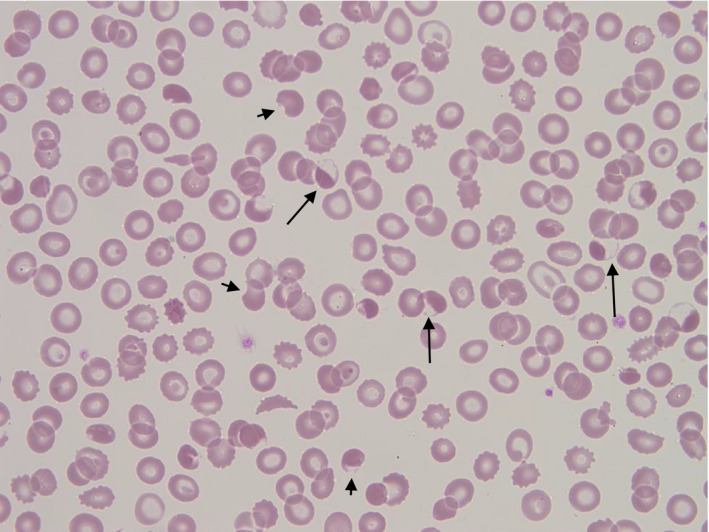

A 9‐year‐old Afro‐Caribbean boy presented with fever, abdominal pain and collapse. Physical examination was normal, as were chest X‐ray and computed tomography of his head. Urinalysis showed microscopic haematuria and proteinuria. A reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) was positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA. His full blood count on presentation showed a haemoglobin concentration of 99 g/l, a mean cell volume (MCV) of 59.7 fl, a reticulocyte count of 89 × 109/l, a white cell count of 8.4 × 109/l and a platelet count of 137 × 109/l. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated at 657 iu/l with an elevated bilirubin of 42 μmol/l and an alanine transaminase of 195 iu/l. A direct Coombs test was negative and the result of a glucose‐6‐phosphate‐dehydrogenase assay was 17.8 iu/g Hb (normal range 8.8–12.8). High performance liquid chromatography showed a haemoglobin A2 of 6.1% suggesting a diagnosis of β thalassaemia trait. Blood film examination (image) showed evidence of oxidative haemolysis with numerous blister and hemighost cells (long arrows), keratocytes (short arrows), irregularly contracted cells and echinocytes. The patient had received no drugs known to cause oxidative haemolysis. The sample was referred to the regional genetics laboratory for further evaluation of possible enzymopathies by Next‐Generation Sequencing. This showed a heterozygous pathogenic variant of HBB, Hb Monroe, which has the phenotype of β0 thalassaemia with no G6PD mutation or evidence of other cause for the profound blood film changes.

Due to a rising LDH of 1370 iu/l and development of heart block, together with an elevated troponin of 884 ng/l, the patient was referred to the regional paediatric cardiac unit for further management and evaluation for a possible Kawasaki disease‐type disorder. He made a full recovery following intravenous methylprednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulin.