Abstract

Older adults have been markedly impacted by the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) pandemic. The American Geriatrics Society previously published a White Paper on Healthy Aging in 2018 that focused on a number of domains that are core to healthy aging in older adults: health promotion, injury prevention, and managing chronic conditions; cognitive health; physical health; mental health; and social health. The potentially devastating consequences of COVID‐19 on health promotion are recognized. The purpose of this article is multifold. First, members of the Healthy Aging Special Interest Group will present the significant difficulties and obstacles faced by older adults during this unprecedented time. Second, we provide guidance to practicing geriatrics healthcare professionals overseeing the care of older adults. We provide a framework for clinical evaluation and screening related to the five aforementioned domains that uniquely impact older adults. Last, we provide strategies that could enhance healthy aging in the era of COVID‐19.

Keywords: older adults, healthy aging, COVID‐19

Key Points

COVID‐19 has challenged existing health promotion paradigms.

Careful screening is strongly recommended during in‐person, virtual, or phone‐based visits.

Members of the AGS Healthy Aging Special Interest Group provide resources to geriatrics healthcare professionals to provide to patients and their caregivers.

Why Does this Paper Matter

Healthy aging is important to an older adult's well‐being and physical function. COVID‐19 has negatively affected older adults making health promoting activities more difficult. Members of the AGS Healthy Aging Special Interest Group provide suggestions to geriatrics healthcare professionals for their patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) pandemic has disrupted routine daily activities of adults aged 65 and older 1 who comprise 17% of the U.S. population, yet represent 31% of cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of intensive care unit admissions, and 80% of deaths. 2 Older adults' weakened immune responses 3 and multimorbidity 4 place them at a 23‐fold higher mortality risk compared with younger adults. 5 Such hazards potentially threaten their physical and emotional well‐being, placing them at higher risk for functional decline, adverse long‐term outcomes, and lower quality of life. 6 The consequences of physical distancing, stay‐at‐home orders, and quarantine measures on health and health promotion should be addressed as the pandemic continues. 7 Older adults who become infected with COVID‐19 and survive are also at higher risk for long‐term sequelae, including frailty, cognitive decline, and reduced immunity. 8

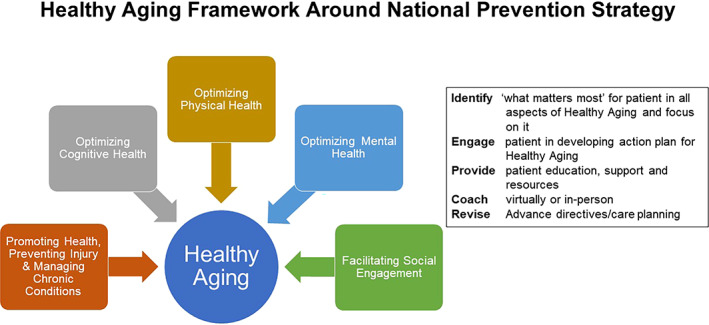

In 2018, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) published a consensus White Paper on Healthy Aging to provide a roadmap for geriatrics healthcare professionals (GHPs), educators, and researchers among its members. 9 Healthy aging is defined as a multidimensional construct of five key health promotion domains focusing on promoting and optimizing: (1) promoting health, preventing injury, managing chronic conditions; (2) cognitive health; (3) physical health; (4) mental health; and (5) facilitating social engagement and resilience. COVID‐19 threatens each of these domains in older adults by compromising short‐ and long‐term outcomes, thereby negatively impacting health and well‐being. Members of the Healthy Aging Special Interest Group recognize the potential devastating consequences of COVID‐19 on health promotion for older adults during the pandemic. Our goal is to provide guidance and practical approaches to GHP seeking to promote healthy aging during the pandemic which align with the AGS White Paper (Figure 1). 9 We focus on the specific needs of older adults and recognize that interventions overlap multiple categories; we refer our readership to geriatricscareonline.org, and healthinaging.org for further resources.

Figure 1.

Healthy aging framework around national prevention strategy in the era of COVID‐19.

1.1. Promoting Health, Preventing Injury, and Managing Chronic Conditions

Physical health and medical comorbidity‐management of older adults have been significantly affected by COVID‐19. Regular primary care provider (PCP) follow‐up (in person, virtual, or phone‐based) optimally allows the management of chronic illnesses, and promotion of physical activity and healthy diets. Older adults are afflicted by multiple chronic conditions 10 and are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID‐19. The PCP plays a key role in identifying common signs of distress and burnout, and assessing an older adult's resiliency (Table 1), and can easily conduct such evaluations during an annual wellness visit. One barrier to optimizing the role of the PCP in supporting healthy aging in disadvantaged communities is the overall lack of access to health care and other resources.

Table 1.

Screening Tools to Promote Healthy Aging during the COVID‐19 Pandemic

| Screen for | Sample Tools | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Advance care planning | State‐specific documentation |

Sample questions could include: Do you have a healthcare proxy? Do you have a living will? |

| Age‐friendly (4M's) | What are your current wishes? Identify what matters most. | |

| Alcohol use | AUDIT‐C | 3‐item, modified version of the 10 question AUDIT instrument for alcohol consumption. A score ≥3 should receive further assessment |

| CAGE | 4‐item interview questions that assist diagnosing alcoholism. Cutoff ≥2 | |

| SMAST‐G | Detects at‐risk alcohol use, alcohol abuse, or alcoholism. Cutoff score ≥2 | |

| Anxiety | GAD‐7 | 7‐item, self‐report questionnaire used in primary care settings for screening and severity measuring of GAD. Cutoff score ≥10 |

| Caregiver fatigue | AMA Caregiver Self‐Assessment Questionnaire | 18‐item, self‐administered tool, sensitive for the detection of depressive symptoms. Cutoff score ≥10 or specific answers to three questions (4, 11, 17, 18) |

| Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview | A 22‐item scale that assesses caregiver perceptions of burden that may affect health, personal, social or financial well‐being. | |

| Cognition | Mini‐Cog | A tool that combines clock‐drawing and 3 item recall. Cutoff score ≥3 |

| Dental | Eating Assessment Tool | A 10‐item self‐administered, symptom‐specific outcome instrument for dysphagia. Cutoff score ≥3 |

| DENTAL | A 6‐item screening tool that determines undetected dental conditions which compromise oral health/decrease quality of life. Cutoff ≥2 | |

| Depression | PHQ‐2 | 2‐item tool to screen for depression. Cutoff score ≥2 |

| GDS‐Short Form | A 15‐item scale that measures depression in older adults. Cutoff score ≥5 | |

| Diet Quality | Powell and Greenberg | 2‐item self‐report questionnaire on fruit and vegetable intake, and consumption of sugary food and drink. Cutoff ≥1 |

| Exercise | Physical Activity Vital Sign | 2‐item screening tool from Exercise is Medicine program. Cutoff ≥150 min |

| Food security | Hunger Vital Sign (USDA food security survey) | Within the past 12 months: (1) worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more; (1) food we bought just didn't last and we didn't have money to get more. Cutoff if: always or sometimes true |

| Resilience | Resilience Scale | The short form of the brief resilience scale, a validated 14‐item scale that can help identify older adults low in resilience |

| Coping Self‐Efficacy | The CSE scale provides a measure of a person's perceived ability to cope effectively with life challenges | |

| Sensory impairment | Hearing | Do you have difficulty with your hearing? |

| Vision | Do you have difficulty with your vision? | |

| Visual acuity (e.g., Snellen Chart) | ||

| Sleep | Epworth Sleepiness Scale | An 8‐question, self‐report tool designed to measure general level of daytime sleepiness. Cutoff ≥10 |

| Social determinants of health | Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool | A 10‐item screening tool developed by CMS that identifies unmet needs across five core domains (housing instability, food insecurity, transportation needs, utility needs, interpersonal safety) |

| Social isolation and loneliness | UCLA 3‐Item Loneliness Scale | UCLA 3‐item loneliness scale to evaluate loneliness includes items related to companionship, belongingness, and isolation. Cutoff ≥6 |

| Steptoe Social Isolation Index | 5‐item index addressing unmarried/not cohabiting status, less than monthly contact with children, family, friends, including face‐to‐face, by telephone, or in writing/email and no participation in social life. Cutoff ≥2 | |

| Substance abuse | Smith's single item | How many times in the past year have you used an illegal drug or used a prescription medication for nonmedical reasons? |

Abbreviations: AMA, American Medical Association; AUDIT‐C, AUDIT‐Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test‐Consumption; BRS, The Brief Resilience Scale; CD‐RISC, The Connor Davidson Resilience Scale; CMS, Centers for Medicaid and Medicare; CSE, Coping Self‐Efficacy Scale; GAD‐7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment; GDA, Geriatric Depression Screen; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; RS, The Resilience Scale for Adults; SMAST‐G, Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, geriatric version; UCLA, University of California Los Angeles; USDA, United States Department of Agriculture.

PCPs can provide patient education, support, and resources, not only monitoring chronic conditions to prevent sudden or subacute illnesses, but also focusing on routine elements of preventive care. We strongly advocate that all older adults should receive their annual influenza vaccination and if they have yet to receive other preventive vaccinations, to do so. These may contribute to trained innate immunity, which may stimulate the adaptive immune system that improves the ability to fight off other types of infection. In ecological studies, rates of COVID‐19 were lower in areas not only with high rates of influenza vaccination, 11 but also with the use of other types of vaccination. 12 Patients may have reservations about receiving vaccinations in medical offices or facilities; yet, we do suggest administration at retail pharmacies. Last, simplifying medication regimens has known benefits but now may be an opportunity to do so.

Older adults are also at‐risk for malnutrition and those at‐risk before the pandemic are even more vulnerable now due to unhealthy eating habits and food insecurity. Food insecurity, defined as the lack of consistent physical, social, and economic access to adequate and nutritious food, has been exacerbated by increased unemployment, poverty, and higher food prices. 13 Before the pandemic, at least 8% of households with an older adult living alone were classified as having food insecurity. 14 That number has increased significantly since its onset. 13 Patients with food insecurity are more likely to need assistance or be dependent in their activities in daily living, and are more likely to have multimorbidity. 14 Food choices and access to food have been impacted because of stay‐at‐home orders and reduced external assistance. 15 Older adults who live in congregate living facilities such as nursing homes, assisted living facilities and retirement communities are at particularly high risk for malnutrition because of COVID‐19 related restrictions. Older adults residing in facilities can no longer eat communally and miss those socialization opportunities which enhance quality of life. 16

GHP should work with older adults to optimize their nutrition, especially now given the clear evidence of malnutrition in this vulnerable population. 17 Although adequate calorie intake is clearly a priority, a well‐balanced diet, centered on non‐processed foods is also important, with limited alcohol intake. 18 Adequate consumption of protein (plant over animal) to counter increased sedentary behavior and increased risk of sarcopenia should be urged. 19 Access to food remains problematic; taking advantage of delivery options from grocery stores, curbside pick‐up, availing of senior‐only hours, or asking family or friends for help with weekly shopping can be helpful. Community social workers can also facilitate locating local meal delivery services. PCPs can provide guidance to patients that can include recommendations to contact their local area Agency on Aging for more information on available resources (e.g., food banks).

High quality sleep is likewise important for good physical, mental, and social health. Many older adults report a change in sleep patterns since the start of the pandemic. 20 Sleep deprivation can have a negative impact on attention, working memory, long‐term memory, and decision making. GHP should ask their older patients about sleep related concerns and where appropriate give recommendations regarding good sleep practices.

Although advance care planning and eliciting values and care preferences are important at any time, they are especially important now. Patients may clearly express their needs and wishes (e.g., intensive care unit admission fully isolated from family, intubation, feeding tubes, hydration), and identify preferences of remaining home, using home health resources, and timely hospice should they succumb to a serious COVID‐19. Having such conversations and including family members and caregivers (using virtually methods) for education about safe and comfortable home care can be invaluable.

Social worker's contribution to the aging population during the pandemic has been invaluable. Irrespective of their site of care, they may provide different resources to older adults in helping combat loneliness and ensuring safety. The resources offered vary widely from individualized therapy to patients to meal delivery services to an older adult's home. Community social workers may have updated community virtual programs to enable seniors to be more engaged. 21

1.2. Cognitive Health

COVID‐19 has been shown to adversely impact the central nervous system with more than 80% of those infected demonstrating some degree of a neurologic complication, including 31.8% with encephalopathy and 11.4% with anosmia. 22 The incidence of COVID‐19 neurologic complications is even higher in older adults. 23 Persistent fatigue is also common. Both the restrictions that have been put in place to protect older adults from COVID‐19 and being infected with COVID‐19 are associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. 24 Older adults with normal cognition at baseline may experience new memory impairment following infection. Those with existing cognitive impairment are at high risk for both acute changes in their level of alertness and a sudden additional deterioration in their cognitive function. 25 These changes are most prominent in those older adults that experienced hypoxia, hypoperfusion, intubation, and sedation. Among older adults with established cognitive impairment, leaving the house and interacting with others can provide cognitive stimulation and preserve physical function. 26 Regrettably, caregivers report that 63% of loved ones with cognitive impairment have experienced cognitive decline during the pandemic, according to an on‐line poll. 27 Hence, establishment and reinforcement of new routines can help to increase predictability and stability in an unpredictable time.

Psychological stress induced by COVID‐19 can also lead to cognitive decline, including reduced attention, impaired learning, memory impairment, difficulty with decision‐making, and impaired problem solving. 28 Social isolation due to stay‐at‐home orders disrupts daily life routines and can impact behavioral symptoms such as agitation, wandering and aggression. Caregivers of patients are also susceptible to the issues addressed above as they work to care for their loved ones. Identifying caregiver fatigue and supporting caregivers is always important, but is of added importance during this pandemic. As GHP, we should be aware of these factors, identify individuals and caregivers at risk and work with both older adults and their caregivers to preserve cognition and cognitive resilience.

Hearing impairment is a recognized risk factor for cognitive impairment and can contribute to acute confusion in older adults with existing cognitive impairment. 29 Verbal communication with older adults who have hearing impairment is complicated by the need to wear a mask. Strategies that can be used to optimize communication with older adults, despite COVID‐19 related restrictions are listed in Table 2. For instance, if hearing is difficult during physical activity (e.g., while walking 6 feet apart), patients can talk with family members on the phone at rest.

Table 2.

Sample Strategies to Enhance Healthy Aging During COVID‐19: Levels of Prevention Model

| Domains | Potential Recommendations | Sample Resources to Guide Geriatric Healthcare Professionals a |

|---|---|---|

| Health, preventing injury and managing chronic conditions | Involve family/friends | Advance care planning: prepareforyourcare.com; theconversationproject.org |

| Books | Blue Zones Kitchen: 100 Recipes to Live to 100, by Dan Buettner | |

| Follow evidence‐based dietary plans | MIND or Mediterranean Diet | |

| oldwayspt.org/traditional‐diets/mediterranean‐diet/mediterranean‐diet‐resources | ||

| General Resources, Chronic Disease | General Resources: www.aarp.org | |

| Osteoarthritis resources: www.arthritis.org/diseases/osteoarthritis, www.arthritis.org/living‐with‐arthritis/tools‐resources/walk‐with‐ease | ||

| The American College of Lifestyle Medicine ‐ using lifestyle to advance healthy aging and chronic disease reduction: www.lifestylemedicine.org | ||

| Wear mask and maintain physical distance | ||

| Cognitive Health | Books | The Alzheimer's Solution, by Dean and Ayesha Sherzai |

| Sleep Hygiene | Aim for 7‐9 hours of restful sleep | |

| Sleep apps: e.g., Calm.com, Sleepio | ||

| Address vision/hearing | Local eye professional and/or audiologist | |

| Educate/support caregiver distress | Take online classes through local community college, etc. | |

| Meditation | Meditation apps: e.g., Headspace | |

| Physical health | Books | The Harvard Medical School Guide to Tai Chi: by Peter Wayne; “Younger Next Year” by Chris Crowley and Henry Lodge |

| Exercise, Tai Chi | Opt for virtual classes or outdoor experiences—be outside in safely | |

| NCOA: recommended exercise programs (Active Choices, Health Moves) | ||

| Geri‐Fit: resistance strength training program—www.gerifit.com | ||

| Silver Sneakers, yoga | ||

| Tai Chi Moving for Better Balance/Chair TaiChi, Suman Barkhas (YouTube) | ||

| Health Moves: home based exercise program www.ncoa.org/resources/program‐summary‐healthy‐moves‐for‐aging‐well/ | ||

| Go4Life: www.nia.nih.gov/health/exercise‐physical‐activity | ||

| Bingocize: www.ncoa.org/resources/bingocize‐program‐summary | ||

| Chair stand for proximal strengthening | ||

| Visit local library for exercise videos (if no internet access) | ||

| Maintain oral health | Visit local dentists (www.ada.org) | |

| Contact local Area Agency on Aging for more resources | ||

| Vitamin D deficiency | Take vitamin D3 800‐2000 units | |

| Mental health | Books | Live More Happy by Darren Morton |

| Engage in virtual psychotherapy | Location of psychotherapy resources: PsychologyToday.com | |

| Limit alcohol consumption: 3 drinks on a given day; 7 drinks per week | Alcohol reduction: www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/thinking‐about‐a‐change/strategies‐for‐cutting‐down/tips‐to‐try.aspx | |

| Attend caregiver groups | Caregiver support groups: www.alz.org | |

| Manage stress through mind‐body practices | Mind‐body practice (meditation, yoga, TaiChi), www.nccih.nih.gov/health/stress | |

| Positive Coping Strategies | ||

| Practice spirituality (online) | ||

| Facilitating social engagement | Books | Resilience (Science of Mastering Life's Greatest Challenges), Steven Southwick |

| Participate in physically distanced or virtual visits with family and friends | Video Chats: Zoom, FaceTime, Google Meet | |

| Attend virtual religious services | ||

| Socialize (telephone, text messaging) | Loneliness/Social Isolation toolkit: populationhealth.humana.com/resources/social‐isolation‐loneliness‐toolkit/ | |

| Social media: Facebook, Twitter | ||

| Encourage letter writing | ||

| Online games and courses for older adults | Online games: https://onlinegamesforseniors.com/ | |

| Coursera: on‐demand video lectures: www.coursera.org/ | ||

| Computer Class for Seniors: https://www.medicarefaq.com/blog/top‐free‐computer‐classes‐for‐seniors/ | ||

| National organization for healthy aging and lifelong learning: www.oasisnet.org | ||

| Other General Resources | Area Agencies: https://www.n4a.org | |

| COVID‐19 resources: https://www.engagingolderadults.org/covid19 |

Based on the experience and suggestions from members of the Health Aging Special Interest Group.

1.3. Physical health

Many interventions aimed at optimizing physical health and mitigating the impact of common conditions during the aging process (e.g., falls prevention, osteoporosis, dental and oral health, and osteoarthritis) 9 have needed to be changed because of fear of COVID‐19 exposure.

COVID‐19 has limited the ability of older adults to stay physically active. Exercise facilities, community/senior centers, long‐term care community classes, and pools have either ceased operations or have curtailed their hours. In some parts of the country, parks have been closed. As these locations re‐open, their access may be limited (hours, reservations needed, lack of transportation) and safety concerns may persist. We understand the need to balance between infection risk from exercising in public spaces and optimizing physical health; it is critical that older adults remain physically active. GHP should promote exercise during the pandemic by providing creative advice and encouragement. Walking is possible with appropriate physical distancing with friends, children, or grandchildren. We can support and urge the participation of older adults in regular on‐line exercise classes. Supporting the use of web‐based nature videos that simulate walking or cycling, or web‐classes that be conducted individually or with a group should be considered. For those where internet connectivity is a challenge, consider engaging a trusted family member to identify or move an old treadmill, exercise bike, or elliptical to a prominent place in the house. Reminding patients that sedentary behavior increases risk of heart disease, declining function, and mortality is important and that waiting until the pandemic is over to return to regular physical activity may prevent or delay a return to baseline. 30 If a patient has had COVID‐19, they should resume exercise gradually. We support and encourage activity around the house to prevent thrombosis; best evidence suggests waiting 2 to 3 weeks to gradually resume exercise if someone has had pulmonary or cardiac symptoms associated with their COVID‐19 infection. 31

Many of the sites where community dwelling older adults were able to gather for exercise or social events such as senior centers and churches have been closed since the beginning of the pandemic, although some are slowly opening up with appropriate precautions. These sites were places where older adults could congregate to participate in evidence based self‐management programs provided by Area Agency on Aging resources and grant funding (see Table 2). For instance, fall prevention programs at congregate centers may have been postponed, and should continue to be encouraged with appropriate supports virtually. In warmer climates, outdoor programs can be considered, being mindful of physical distancing. Limiting activities for older adults to what they can do within their own homes has been encouraged, and some older adults have resources (Wi‐Fi and devices) to livestream chair exercise classes and other informational and social activities directly into their homes.

Regular dental care has often been omitted or delayed during the pandemic. Early in the pandemic timeline (March 2020) the American Dental Association recommended curtailment of all but urgent or emergency care partly due to concerns for conservation of personal protective equipment for other healthcare colleagues. 32 However, data collected since then have supported a change in policy and since August 2020 all dental care is considered essential health care and should be resumed. 33 The risk of COVID‐19 transmission to patients during dental care is believed to be low; in fact, literature suggests that rates of COVID‐19 in U.S. dentists ~0.9%. 34 Transmission risk for dental care providers exists due to the aerosolization and droplets produced during dental care, but is effectively limited by the use of personal protective equipment such as N‐95 masks, goggles, facial shields, disinfection between patients, and handwashing. 35 GHP should encourage patients to contact their dental care providers about the safety of resuming both prophylactic and necessary dental care using appropriate precautions. 36

GHP can assist their patients and families to optimize their health by referring them to digital resources whenever possible. These resources were available before pandemic conditions, but nearly all are available now in new modalities as they have had to pivot to a new way of interacting with participants in a virtual world. Although many of the sites have physically closed, their resources are often still available digitally for older adults who have the ability and access to technology and the internet. Resources available on websites as self‐paced modules or phone calls to those who lack access to internet‐based technology, and online support groups and information about healthy living with arthritis (see Table 2).

1.4. Mental health

COVID‐19 has impacted everyone's psychological wellbeing, including older adults. It is worth noting, that despite ageist assumptions, older adults generally enjoy good mental health, akin to that of younger adults. 37 Older adults have also been shown to be better able to cope with both COVID‐19 and non‐COVID‐19 related stress. 38 Many older adults also demonstrate high degrees of resiliency, described as the ability to maintain the best possible adjustment when facing challenging circumstances. 39 GHP should however be aware that not all older adults are coping well with COVID‐19 related stress. Assessing gaps in older adults for resiliency should be considered.

Loneliness, clinically defined as a sense of existential isolation and being without outlets for emotional connection, is one important factor to address in facilitating coping. A large national survey identified a clear increase in loneliness corresponding with the early months of the pandemic and associated isolation precautions. 40 Those identified as being at notably increased risk were women, as well as those who live alone, who are not working, who are of lower socioeconomic status, and who report poorer physical and mental health at baseline. In later months, data suggested that the use of technology (e.g., social media) has mitigated these concerns to a degree, but certainly should not be the only strategy for addressing isolation.

The role of ageism and COVID‐19 is of concern, where studies have the risk of minimization of the value of an older adult's life, both among healthcare providers and the general public. 41 These findings are concerning but also form the foundation for elder abuse. Elder abuse rates have risen since the pandemic's onset, and elder abuse is often unreported. 42 Like in the pre‐pandemic era, it is often perpetrated by family members. Infection control precautions and associated emotional stresses have complicated all these dynamics.

Rates of substance use have increased considerably compared to the same period in 2019. 43 Liquor sales were 55% higher in March 2020 compared to a year earlier with a 262% increase in online sales. 44 Self‐reported alcohol consumption also increased, with a majority reporting an increase in drinking on 1 more day per month and an increase in problematic drinking for women. 18 Given the elevated risk of suicide among older adults with both alcohol use disorder and depression, 45 it is imperative GHP appropriately identifies and manages older patients suffering with substance use, proactively assessing risk and counseling to curb use and foster healthy aging.

1.5. Facilitating Social Engagement

Physical distancing, resulting for many in social isolation, is a cornerstone of efforts to reduce the spread of COVID‐19. Social isolation has a negative impact on mental, physical, and emotional health, increasing risk for anxiety, insomnia, depression, cognitive decline, a weakened immune system, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular diseases, cancer, and mortality. 46 Social relationships can be considered “the single most important predictor of happiness and longevity.” 47 Older adults who live alone or reside in congregate living arrangements (e.g., nursing homes, assisted living, senior housing) are at particularly high risk for the negative effects of social isolation. Although protecting older adults from getting COVID‐19 is a priority, we need to be more aware of the negative impact of physical distancing and social isolation on other aspects of an older adult's health. 48 Promoting social connectedness for older adults during the pandemic is an important goal. The mechanism by which to achieve this remains challenging. Although virtual connections are inferior to face‐to‐face interpersonal relationships, communication by phone, text, or video chat can be helpful. The United Kingdom has used regular scheduled phone calls in isolated older adults who are lonely for many years, as a means of providing support and monitoring the physical and emotional health of older adults who live alone. 49 Similar programs have been initiated in response to the pandemic. These should be encouraged, supported, and expanded both during the pandemic and after.

Social media can be used for positive social connectivity and not to spread fear, uncertainty, and intolerance. 47 Working in collaboration with other societal and professional organizations can strengthen positive social connectivity, by sharing reliable health information and recommendations. Nurturing personal resilience is as important as building community resilience. Our Interest Group feels that building a strong community may help mitigate the impact of coronavirus. Neighborhoods' and communities' strong relationships and partnerships with policy makers may help to utilize resources, reduce health disparities, and buffer the impacts of pandemic‐related stress. 50 Adversity creates an opportunity to reflect and find a way to bounce back even stronger than before. Physical isolation does not mean social disconnectedness. It might create an opportunity to build even stronger and more meaningful connectedness.

In facilities with communal dining, the benefit of opening up with physical distancing rules may outweigh the risk of getting sick. Before the pandemic, many family members would help their loved ones eat during mealtimes. Once again, with the understanding that there is a balance between keeping these vulnerable older adults safe, and promoting overall good health, allowing a limited number of visitors to come during meal times so that residents do not need to eat alone is an important consideration for such facilities. Visitors could be asked to follow the same state specific surveillance protocols currently in place for the staff of these facilities. In colder climates where residents need to eat indoor, empiric supplementation of Vitamin D may be considered.

2. CONCLUSION

Older adults have not only borne the brunt of COVID‐19 illness and death, but they have also suffered disproportionately from the restrictions put in place to limit the spread of the virus. AGS is an advocate for optimizing good health in old age. Although COVID‐19 has challenged this goal, members of the AGS Healthy Aging Special Interest Group remain committed to promoting healthy aging both during and after the current pandemic and educating our patients and to our colleagues. Supplementary Table S1 highlights overarching themes that can be helpful to all GHP.

COVID‐19 has forced our society and patients to change how to engage in health promotion activities. There needs to be a balance between keeping older adults safe from the ravages of COVID‐19 and optimizing their overall health. Both the positive and negative effects of the plans put in place to keep older adults safe need to be measured. This can be challenging because identifying the number of COVID‐19 cases and associated complications is relatively easy, but identifying the negative impact of COVID‐19 related restrictions on the overall health of older adults is much more difficult. When it is clear that the negative impact on older adults is greater than the positive, these plans need to be adjusted. Engaging GHP in pandemic planning should be considered in engaging communities and older adults as outlined in the White Paper.

At the time of this writing, there is a light at the end of the tunnel with the emergency use authorization approval of the first two vaccines for widespread use. Although older adults are prioritized over other lower‐risk demographic groups (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations.html), this pandemic has undoubtedly altered our routine lifestyle but perhaps has provided opportunities for changes in healthcare delivery. Advocacy efforts should prompt policymakers in changing reimbursement systems by promoting technology‐based endeavors, particularly in under‐represented populations and under resourced areas. Those working with older adults help optimize their health and function; we need to be aware of the challenges in achieving this goal posed by COVID‐19 and the efforts to limit its spread. We need to continue to work with older adults, their families, and caregivers, to make sure that our efforts to promote healthy aging are sustained in the face of the pandemic. Continuing to dispel ageism in health promotion interventions and advocating for additional training to non‐geriatric providers through interprofessional learning endeavors is needed. We need to be a part of the discussions and plans put in place to limit the spread of the pandemic, so that these plans are sensitive to the overall health needs of older adults.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1: Overarching themes for geriatric healthcare professionals caring for older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Mulhausen for encouraging us to write this piece and Nancy Lundebjerg for her comments and suggestions.

Financial Disclosure

JAB is funded in part by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AG051681 and R01AG067416. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other sponsors. The funders had no role in the design, conduct or analysis of the study. KD is funded in part by the Deerbrook Charitable Trust, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under Award Number R18HS027277, Research Retirement Foundation Award Number 2020125, and the Interdisciplinary Research Program at the University of Texas at Arlington. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views any of the sponsors. The funders had no role in the design, conduct or analysis of this study. EE is funded in part by the Oregon Clinical & Translational Research Institute (UL1TR002369‐01) of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institute of Health. KG: None to report. HK: None to report. DL: None to report. JL is funded in part by the Clinical Education Research Scholars Program of the Brigham and Women's Hospital Department of Medicine. SMF: None to report.

Conflict of Interest

JAB holds two patents on an instrumented resistance bands. He holds equity in SynchroHealth, LLC. PPC is on the Board of Directors of the American Geriatrics Society. SMF is on the Board, and serves as Director of Clinical Studies of Rochester Lifestyle Medicine Institute, a non‐profit organization with a mission “to establish Lifestyle Medicine, especially the adoption of Whole‐Food Plant‐Based nutrition, as the foundation for health and the healthcare system.”

Author Contributions

JAB: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. KD: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. EE: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. KG: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. HK: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. DL: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. JL: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. PPC: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version. SMF: conceived, designed, interpreted data, prepared manuscript, approved final version.

Sponsor's Role

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. Górnicka M, Drywień ME, Zielinska MA, Hamułka J. Dietary and lifestyle changes during COVID‐19 and the subsequent lockdowns among Polish adults: a cross‐sectional online survey PLifeCOVID‐19 study. Nutrients. 2020;12:2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) – United States, February 12‐March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343‐346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Csaba G. Immunity and longevity. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2019;66:1‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:E1‐E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age‐related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID‐19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52:154‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mukhtar S. Psychological impact of COVID‐19 on older adults. Curr Med Res Pract. 2020;10:201‐202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palmer K, Monaco A, Kivipelto M, et al. The potential long‐term impact of the COVID‐19 outbreak on patients with non‐communicable diseases in Europe: consequences for healthy ageing. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1189‐1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Friedman SM, Mulhausen P, Cleveland ML, et al. Healthy aging: American Geriatrics Society White Paper executive summary. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:17‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boyd C, Smith CD, Masoudi FA, et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary for the American Geriatrics Society Guiding Principles on the Care of Older Adults With Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:665‐673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amato M, Werba JP, Frigerio B, et al. Relationship between influenza vaccination coverage rate and COVID‐19 outbreak: an Italian ecological study. Vaccines. 2020;8:535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pawlowski C, Puranik A, Bandi H, et al. Exploratory analysis of immunization records highlights decreased SARS‐CoV‐2 rates in individuals with recent non‐COVID‐19 vaccinations. medRxiv ; 2020: 10.1101/2020.07.27.20161976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Niles MT, Bertmann F, Belarmino EH, Wentworth T, Biehl E, Neff R. The early food insecurity impacts of COVID‐19. Nutrients. 2020;12:2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pooler JA, Hartline‐Grafton H, DeBor M, Sudore RL, Seligman HK. Food insecurity: a key social determinant of health for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:421‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Monahan C, Macdonald J, Lytle A, Apriceno M, Levy SR. COVID‐19 and ageism: how positive and negative responses impact older adults and society. Am Psychol. 2020;75:887‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jenq GY, Mills JP, Malani PN. Preventing COVID‐19 in assisted living facilities – a balancing act. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1106‐1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Visser M, Schaap LA, Wijnhoven HAH. Self‐reported impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on nutrition and physical activity behaviour in Dutch older adults living independently. Nutrients. 2020;12:3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2022942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, et al. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all‐cause and cause‐specific mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1453‐1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alhola P, Polo‐Kantola P. Sleep deprivation: impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:553‐567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berg‐Weger M, Morley JE. Editorial: loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic: implications for gerontological social work. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:456‐458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liotta EM, Batra A, Clark JR, et al. Frequent neurologic manifestations and encephalopathy‐associated morbidity in Covid‐19 patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7:2221‐2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID‐19 in 153 patients: a UK‐wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:875‐882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, et al. Post‐discharge persistent symptoms and health‐related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID‐19. J Infect. 2020;81:e4‐e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manca R, De Marco M, Venneri A. The impact of COVID‐19 infection and enforced prolonged social isolation on neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with and without dementia: a review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:585540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Devita M, Bordignon A, Sergi G, Coin A. The psychological and cognitive impact of Covid‐19 on individuals with neurocognitive impairments: research topics and remote intervention proposals. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1179‐1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Study finds many americans in the dark about dementia and alzheimer's disease, uncovers how pandemic is affecting brain health. MDVIP. Boca Raton, FL: MDVIP; 2020:2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zarrabian S, Hassani‐Abharian P. COVID‐19 pandemic and the importance of cognitive rehabilitation. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2020;11:129‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fischer ME, Cruickshanks KJ, Schubert CR, et al. Age‐related sensory impairments and risk of cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1981‐1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Rezende LF, Rodrigues Lopes M, Rey‐López JP, Matsudo VK, Luiz Odo C. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Metzl JD, McElheny K, Robinson JN, Scott DA, Sutton KM, Toresdahl BG. Considerations for return to exercise following mild‐to‐moderate COVID‐19 in the recreational athlete. HSS J. 2020;16:102‐107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. ADA Calls Upon Dentists to Postpone Elective Procedures. American Dental Association; 2020. https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2020-archives/march/ada-calls-upon-dentists-to-postpone-elective-procedures.

- 33. Guidance for Dental Settings: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Dental Settings During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Pandemic. Vol 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Estrich CG, Mikkelsen M, Morrissey R, et al. Estimating COVID‐19 prevalence and infection control practices among US dentists. J Amer Dent Assoc. 2020;151:815‐824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Epstein JB, Chow K, Mathias R. Dental procedure aerosols and COVID‐19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;S1473‐3099(20):30636‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19): implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584‐595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Erskine J, Kvavilashvili L, Myers L, et al. A longitudinal investigation of repressive coping and ageing. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:1010‐1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Klaiber P, Wen JH, DeLongis A, Sin NL. The ups and downs of daily life during COVID‐19: age differences in affect, stress, and positive events. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;gbaa096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Masten AS. Resilience in individual development: successful adaptation despite risk and adversity. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, eds. Educational Resilience in Inner‐City America: Challenges and Prospects. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malani P, Kullgren J, Solway E, Piette J, Singer D, Kirch M. Longeliness Among Older Adults Before and During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: National Poll on Healthy Aging Team. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jimenez‐Sotomayor MR, Gomez‐Moreno C, Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis E. Coronavirus, ageism, and twitter: an evaluation of tweets about older adults and COVID‐19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1661‐1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malik M, Burhanullah H, Lyketsos CG. Elder abuse and ageism during COVID‐19. Psychiatric Times. 2020;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Czeisler M, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID‐19 pandemic – United States, June 24‐30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049‐1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rebalancing the COVID‐19 effect on alcohol sales, vol 2020. The Nielsen Company, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blow FC, Brockmann LM, Barry KL. Role of alcohol in late‐life suicide. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:48s‐56s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Holt‐Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta‐analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smirmaul BPC, Chamon RF, de Moraes FM, et al. Lifestyle medicine during (and after) the COVID‐19 pandemic. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;15:60‐67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sepúlveda‐Loyola W, Rodríguez‐Sánchez I, Pérez‐Rodríguez P, et al. Impact of social isolation due to COVID‐19 on health in older people: mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:938‐947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Loneliness in the elderly: how to help. Service NH, 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Duane AM, Stokes KL, DeAngelis CL, Bocknek EL. Collective trauma and community support: lessons from detroit. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:452‐454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Overarching themes for geriatric healthcare professionals caring for older adults.