Abstract

Background

As in many fields of medical care, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) resulted in an increased uncertainty regarding the safety of allergen immunotherapy (AIT). Therefore, the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) aimed to analyze the situation in different countries and to systematically collect all information available regarding tolerability and possible amendments in daily practice of sublingual AIT (SLIT), subcutaneous AIT (SCIT) for inhalant allergies and venom AIT.

Methods

Under the framework of the EAACI, a panel of experts in the field of AIT coordinated by the Immunotherapy Interest Group set‐up a web‐based retrospective survey (SurveyMonkey®) including 27 standardized questions on practical and safety aspects on AIT in worldwide clinical routine.

Results

417 respondents providing AIT to their patients in daily routine answered the survey. For patients (without any current symptoms to suspect COVID‐19), 60% of the respondents informed of not having initiated SCIT (40% venom AIT, 35% SLIT) whereas for the maintenance phase of AIT, SCIT was performed by 75% of the respondents (74% venom AIT, 89% SLIT). No tolerability concern arises from this preliminary analysis. 16 physicians reported having performed AIT despite (early) symptoms of COVID‐19 and/or a positive test result for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2).

Conclusions

This first international retrospective survey in atopic diseases investigated practical aspects and tolerability of AIT during the COVID‐19 pandemic and gave no concerns regarding reduced tolerability under real‐life circumstances. However, the data indicate an undertreatment of AIT, which may be temporary, but could have a long‐lasting negative impact on the clinical care of allergic patients.

Keywords: allergen immunotherapy (AIT), COVID‐19, pandemic, SARS‐CoV‐2, survey

This is the first report of an international retrospective survey in atopic diseases investigating practical aspects and tolerability of AIT during the COVID‐19 pandemic. For patients (without any current symptoms to suspect COVID‐19), 60% of the respondents informed of not having initiated SCIT, 35% SLIT, and 40% venom AIT in the induction phase of AIT though planned. For the maintenance phase of AIT, SCIT was performed by 75%, SLIT by 89%, and venom AIT by 74% of the respondents as regularly planned. Data indicate a (temporary) undertreatment of AIT, but gave no concerns regarding reduced tolerability under real‐life circumstances. Abbreviations: AIT, allergen immunotherapy; COVID‐19, Coronavirus disease 2019; SCIT, subcutaneous Immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual Immunotherapy; VIT, venom immunotherapy.

Abbreviations

- AIT

allergen immunotherapy

- ARIA

allergy and its impact on asthma

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- DGAKI

German Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- EAACI

European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- ENT

ear‐nose‐throat

- HAART

highly active antiretroviral therapy

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SCIT

subcutaneous immunotherapy

- SLIT

sublingual immunotherapy

- VIT

venom immunotherapy

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. INTRODUCTION

A new strain of coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) was first reported in China in December 2019 and has led to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) of global relevance. 1 The disease has been diagnosed all over the globe and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic in March, 2020. 2 To date, there are still limitations in diagnostic methods, epidemiological data, and accuracy in treatments. 3 , 4 The wide range of clinical presentations from asymptomatic patients to multi‐organic disease adds uncertainty in the prognosis and evolution. 5 , 6 Although the advances in the recognition of the disease and the prevention of a fatal evolution have been huge, there are still many open questions to be answered and further investigated. 7 This research facilitates the best approach to this new disease and the optimal management of patients in allergy clinics and practices. 8 , 9 , 10

Social and economic life disruptions have been and still are very relevant. Social distancing, the use of face masks and the increase of hygiene in general and specially in hands are the cornerstone of prevention. 11 , 12 Moreover, our medical practices have adapted to the difficult situation, leading to a new concept in the patients’ treatment. 13 Practical recommendations have been developed for improvement of care of allergic patients in daily routine 8 , 9 , 14 , 15 and telemedicine has aroused as a very valuable tool. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

During the current pandemic, the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) has proposed several Position Papers and clinical recommendation for daily clinical care of allergic patients. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25

One of the most important therapies in allergic patients is allergen immunotherapy (AIT) as the only disease‐modifying treatment option in IgE‐mediated allergic diseases. 26 , 27 AIT has been shown to decrease symptoms, reduces the risk of developing asthma in patients with allergic rhinitis and improve quality of life and also to have long‐term efficacy after cessation of the three‐year course of treatment. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Current administration can be by subcutaneous (SCIT) injections or sublingual (SLIT) drops or tablets. 32 , 33 The underlying mechanisms of tolerance induction have been investigated and better understood throughout recent years. 34 However, the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic has raised uncertainties regarding the safety of AIT treatment under the current circumstances. One early statement of the EAACI and the “Allergy and Its Impact on Asthma” (ARIA‐)initiative outlined practical recommendations on AIT. 23 If COVID‐19 is suspected or confirmed, all kinds of AIT should be temporally interrupted as a general rule in infectious diseases. 33 , 35 , 36

If the patient is free of symptoms without evidence of the disease, SLIT can be administered at home supported by telemedicine. This option can help in maintaining adherence to treatment as well as in follow‐up of allergic disease evolution and confirmation of absence of COVID‐19. In an earlier clinical trial on SLIT in grass pollen‐allergic highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)‐treated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐positive patients were reported to be safe without any signal for any significant alteration of CD4‐positive T‐cell counts and HIV load. 37 Concerning SCIT, it should also be continued regularly in COVID‐19 symptom‐free patients without evidence of the disease, especially if AIT is indicated for the treatment of life‐threatening conditions such as venom allergy. 23 As visits to clinics can be postponed, the administration of SCIT in respiratory allergy can also be delayed a few weeks under some circumstances, to minimize in‐person visits at the allergy clinic. If AIT is paused due to active COVID‐19 infection or due to visit restrictions (eg, during lockdown scenarios), it should be re‐initiated as soon as possible adjusting the doses properly depending on the summary of product characteristics of the individual AIT product. 33

However, these recommendations have been proposed as experts’ consensus to support the practitioner with sound standard in performing AIT during the current circumstances. Due to the nature of the pandemic, these recommendations could not be based on clinical data from a prospective clinical trial. Therefore, the EAACI provided a survey to evaluate the impact of the current restrictions as well as the performance of AIT in the clinical routine. The intention of this retrospective survey was to analyze the situation in different countries worldwide and to systematically report all information gained regarding practical aspects and general tolerability of SLIT, SCIT, and venom AIT during the pandemic. Based on the data obtained from this survey, real world evidence will be accumulated of practices during this pandemic that will provide valuable insights and be the basis for future recommendation on how to manage AIT in future pandemics.

2. METHODS

The corresponding author, together with the EAACI Immunotherapy Interest group members, elaborated 27 key questions on practical aspects in AIT routine and specific tolerability under the COVID‐19. These are divided into four general domains: a) Basic information (Q1–Q11), b) Management of AIT in patients without any current symptoms to suspect a COVID‐19 infection (Q12–Q21), c) Management of AIT in patients despite (early) symptoms of a COVID‐19 infection and/or positive test result (Q22–Q26) and d) Consequences for AIT management in the 2nd half of 2020 in case that SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission persists (Q27). This questionnaire was then formally approved by the leadership of the EAACI and made available for physicians worldwide through the SurveyMonkey online platform 38 between 7 July 2020 and 28 July 2020, directly to an anonymized central database.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Domain a) Basic information (Q1–Q11)

In total, the survey was answered by 417 physicians and allied health professionals. 69% of the respondents were EAACI members, 22% EAACI Junior‐members and 9% non‐EAACI members. Most were physicians in Spain (9%), Mexico (6%), Italy (6%), Turkey (5%), and in other countries (all <5%) (Table S1, continental distribution Figure 1). They worked in university hospitals (42%), followed by private practices (24%), public hospitals (18%), private hospitals (9%), and others. Most of the respondents were clinicians completely or partially committed to both pediatric and adult allergic patients (48%), followed by clinicians completely or partially committed to adult patients only (27%) or to pediatric patients only (20%), allied health professionals (2%), and others (2%). 68% of the respondents were allergists, followed by pediatricians (12%), Ear‐Nose‐Throat (ENT) specialists (5%), pulmonologists (5%), internal medicine specialists (3%), dermatologists (2%), and others. Most respondents (64%) had experience in AIT for more than 10 years (Table S2).

FIGURE 1.

Continental distribution of respondents of survey

In total, 44% reported having national guidelines or Position Papers/Consensus Statements in place, whereas 46% reported not to have these documents available on the national level. In addition, 42% of the respondents reported following national or international guidelines or Position Papers/Consensus Statements for the management of AIT during the COVID‐19 pandemic in daily practice and 38% reported following a similar strategy as recommended in these guidances before being aware of these documents. 42% of the respondents reported that face‐to‐face visits were replaced by phone calls for follow‐up consultations, but to maintain consultations in newly referred patients. In contrast, almost one out of three respondent (30%) informed having replaced all face‐to‐face consultations by phone calls as a general rule (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Management of AIT practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Q9–Q11)

| Responses (n = 346) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Q9. Are there any national guidelines or Position Papers/Consensus for the management of AIT during the COVID−19 pandemic available in your country? | ||

| Yes | 153 | 44.22 |

| No | 160 | 46.24 |

| I do not know | 33 | 9.54 |

| Q10. Do you follow any national or international (eg, EAACI, WHO, and AAAAI) Position Paper/Consensus for the management of AIT during the COVID−19 pandemic? | ||

| Yes, they were helpful to decide the best strategy to follow | 145 | 41.91 |

| Yes, but we were already following a similar strategy | 132 | 38.15 |

| No, we followed a different strategy | 33 | 9.54 |

| I do not know | 29 | 8.38 |

| Other | 7 | 2.02 |

| Q11. Health care provided to your allergic patients during the COVID−19 lockdown (at the hardest moment)? | ||

|

Stop both first and follow‐up consultations |

33 | 9.54 |

| Replace face‐to‐face visits by phone calls for all patients | 103 | 29.77 |

| Replace face‐to‐face visits by phone calls for follow‐up, but to maintain face‐to‐face visits for new patients | 146 | 42.20 |

| Maintain face‐to‐face visits for all patients | 36 | 10.40 |

| Other | 28 | 8.09 |

Abbreviations: AAAAI, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; AIT, Allergen Immunotherapy; COVID‐19, Coronavirus disease 2019; EAACI, European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; WHO, World Health Organization.

3.2. Domain b) Management of AIT in patients without any current symptoms to suspect a COVID‐19 infection (Q12–Q21)

In this category, almost 60% of the respondents reported not to initiate SCIT for inhalant allergies for the induction phase of AIT, but to postpone the start of SCIT to a timepoint after the lockdown. 16% answered to “switch” the route of allergen‐application from SCIT to SLIT and only 10% having initiated SCIT as planned (under ordinary, non‐pandemic circumstances). In patients with SCIT for venom allergies, still 40% of the respondents decided to postpone the treatment to a time‐window after the pandemic and only 25% reported to initiate SCIT as planned under ordinary circumstances. For SLIT, 48% of the respondents informed having initiated this therapy as planned under regular circumstances (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Initiation of AIT in patients without symptoms to suspect COVID‐19 (Q12‐Q14)

| Responses (n = 329) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Q12. SCIT for inhalant allergies, please select the applied option for the initiation during the COVID−19 lockdown in general. In case of evolving conditions, select the one followed at the hardest moment of the lockdown | ||

| Not to initiate, but to postpone the initiation to a time point after the pandemic | 194 | 58.97 |

| To initiate, but amend the up dosing schedule | 23 | 6.99 |

| To initiate as planned under regular circumstances | 33 | 10.03 |

| To initiate SLIT as alternative application route and self‐administration | 53 | 16.11 |

| Other | 26 | 7.90 |

| Q13. SCIT for venom allergies (bee/wasp venom), please select the applied option for the initiation during the COVID−19 lockdown in general. In case of evolving conditions, select the one followed at the hardest moment of the lockdown | ||

| Not to initiate, but to postpone the initiation to a time point after the pandemic | 129 | 39.21 |

| To initiate, but amend the up dosing schedule | 56 | 17.02 |

| To initiate as planned under regular circumstances | 82 | 24.92 |

| Other | 62 | 18.84 |

| Q14. SLIT for inhalant allergies, please select the applied option for the initiation during the COVID−19 lockdown in general. In case of evolving conditions, select the one followed at the hardest moment of the lockdown | ||

| Not to initiate, but to postpone the initiation to a time point after the pandemic | 114 | 34.65 |

| To initiate, but amend the up dosing schedule, for example, by less dosage | 24 | 7.29 |

| To initiate as planned under regular circumstances | 158 | 48.02 |

| Other | 33 | 10.03 |

Abbreviations: AIT, allergen immunotherapy; COVID‐19, Coronavirus disease 2019; SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy.

For patients during the maintenance phase of AIT treatment (Figure 2, Table S3), 41% of the respondents reported to continue SCIT for inhalant allergies, but to extend the intervals between injections whereas 33% reported continuing SCIT as planned under regular circumstances. Moreover, 12% decided to pause the treatment during the pandemic. Interestingly, 6% of the respondents informed about having switched the application route from SCIT to SLIT. For patients with venom allergies, it was reported that SCIT was continued as planned under regular circumstances by 39% of the respondents whereas the treatment schedule was amended by 35%. Finally, a complete interruption of SCIT with venom was reported by 8% of the respondents. For SLIT in patients with inhalant allergies, 83% of the respondents informed to have continued treatment as planned under regular circumstances and a dose reduction was reported by only 6%.

FIGURE 2.

Continuation of AIT in patients without symptoms to suspect COVID‐19. Abbreviations: SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy

In patients without any current symptoms to suspect a COVID‐19 infection, the onset of adverse reactions during AIT for inhalant allergies was reported by 4% of the respondents for SCIT and 6% for SLIT in the initiation phase of treatment whereas it was 2% for SCIT and 4% for SLIT in the maintenance phase (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Adverse events of AIT in patients without symptoms to suspect COVID‐19 (initiation and maintenance) (Q18–21)

| Responses (n = 305) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Q18. SCIT in the initiation period: | ||

| SCIT was well tolerated | 294 | 96.39 |

| SCIT lead to significant adverse event | 11 | 3.61 |

| Q19. SLIT in the initiation period: | ||

| SLIT was well tolerated |

288 |

94.43 |

| SLIT lead to significant adverse event | 17 | 5.57 |

| Q20. SCIT in the maintenance period: | ||

| SCIT was well tolerated | 299 | 98.03 |

| SCIT lead to significant adverse event | 6 | 1.97 |

| Responses (n = 299) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Q21. SLIT in the maintenance period: | ||

| SLIT was well tolerated | 288 | 96.32 |

| SLIT lead to significant adverse event | 11 | 3.68 |

Abbreviations: AIT, Allergen Immunotherapy; COVID‐19, Coronavirus disease 2019; SCIT, Subcutaneous Immunotherapy; SLIT, Sublingual Immunotherapy.

3.3. Domain c) Management of AIT in patients despite (early) symptoms of a COVID‐19 infection and/or positive test result for a SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Q22–Q26)

16 out of 305 respondents answering this part of the questionnaire reported having treated patients despite (early) symptoms of COVID‐19 and/or positive test result for a SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Table 4). During the initiation phase of SCIT, significant adverse events were reported by one physician, whereas the remaining informed that SCIT was well tolerated without increased rates of adverse events. For SLIT, all respondents informed that no adverse events developed in this particular subgroup of patients treated. During the maintenance phase of AIT treatment, significant adverse events have been reported by one respondent for SCIT again whereas this has not been noted for SLIT‐treated patients (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Patients with AIT and COVID‐19 symptoms and/or positive test result for SARS‐CoV‐2 (Q22)

| Responses (n = 305) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Q22. Did your patients receive AIT despite (early) symptoms of COVID−19 and/or positive test result for a SARS‐CoV−2 infection? | ||

| Yes | 16 | 5.25 |

| No | 289 | 94.75 |

Abbreviations: AIT, Allergen Immunotherapy; COVID‐19, Coronavirus disease 2019; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

TABLE 5.

Adverse events of AIT (initiation and maintenance) in patients with symptoms of COVID‐19 infection and/or positive test for SARS‐CoV‐2 (Q23–Q26)

| Responses (n = 14) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Q23. SCIT during the initiation period: | ||

| SCIT was well tolerated | 13 | 92.86 |

| SCIT lead to significant adverse event | 1 | 7.14 |

| Q24. SLIT during the initiation period: | ||

| SLIT was well tolerated | 14 | 100 |

| SLIT lead to significant adverse event | 0 | 0 |

| Q25. SCIT during the maintenance period: | ||

| SCIT was well tolerated | 13 | 92.86 |

| SCIT lead to significant adverse event | 1 | 7.14 |

| Q26. SLIT during the maintenance period: | ||

| SLIT was well tolerated | 14 | 100 |

| SLIT lead to significant adverse event | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: AIT, allergen immunotherapy; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy.

3.4. Domain d) Consequences for AIT management in the 2nd half of 2020 in case that SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission persists (Q27)

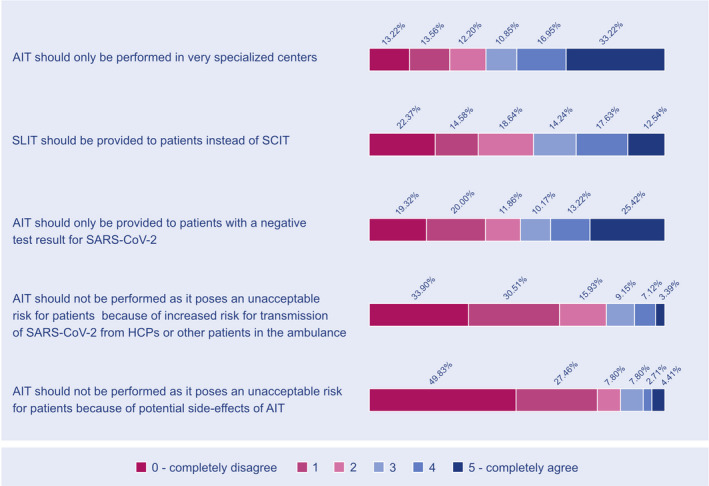

The survey ended by indicating the respondents’ opinions about next strategies regarding the future management of AIT for the second half of 2020 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Consequences for AIT practical considerations in second half of 2020 (if the risk for SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission persists). Abbreviations: AIT, allergen immunotherapy; HCPs, healthcare providers, SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy

4. DISCUSSION

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of practical aspects and safety of AIT in a real‐world setting under the current COVID‐19 pandemic. Other surveys have been launched in order to understand the perception and the impact of the pandemic on patient care and decision‐making in other medical disciplines such as, for example, urology, neurology, and pneumology. 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 This is the first report of an international survey in the field of atopic diseases with a special focus on AIT.

More than 400 physicians and allied health professionals from all over the world have responded to the call of the EAACI. They provided (anonymized) data about their experiences with AIT during this pandemic. A first interesting finding is that almost every second respondent indicated that there has been a lack of recommendations from learned societies on AIT during the pandemic on the national level. However, available Position Papers with concrete clinical guidance 8 , 9 , 23 were considered to be helpful for daily routine in AIT by the majority. The EAACI‐/ARIA‐Position Paper on “Handling of allergen immunotherapy in the COVID‐19 pandemic” 23 has been adapted to the national situation in German‐speaking countries Austria, Switzerland, and Germany in a long version 43 and a pocket‐guide. 44 Besides a country‐specific survey has been launched by the German Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI) to investigate the particular situation in these countries regarding the impact of these guidelines on the clinical routine. 45 Our analysis may help to further investigate national specification of AIT routine care and compliance with national recommendation. Interestingly, almost 40% of the respondents reported that a similar strategy taking care of allergic patients during the pandemic had been followed before becoming aware of the international guidances (Table 1). This fact can be explained by the broad expertise of the participating physicians on AIT and their compliance in following evidence‐based recommendations in AIT guidelines in general. 28 , 31

Telemedicine such as phone calls or videoconferences has been demonstrated as a convenient and sufficient opportunity to interact with patients remotely in certain situations, for example, to improve patient adherence to treatment in general, 46 but also to optimize care of allergic patients 17 especially in the current pandemic. 16 As such, this form of consultation is an ideal tool to differentiate between allergic symptoms and COVID‐19 symptoms, to triage potentially infected patients accordingly as well as to optimize and prioritize treatment in the current pandemic. Adherence to sublingual treatment in AIT, as well as accuracy in self‐application of biologics, has met an excellent tool in telemedicine for its follow‐up and support. 9 , 22 The high number of more than 40% of respondents deciding to replace face‐to‐face visits by remote follow‐up consultations (Table 1) indicates that this medium is indeed becoming a useful tool in routine patient care. However, linked to this information has been the willingness to maintain in‐person consultations for newly referred patients and for prescribing AIT. Of note, 10% stopped both first and follow‐up visits and the same number of respondents maintained in‐person consultations for all patients. This results may indicate that the potential of telemedicine has not been fully reached. Besides it is not clear if country‐specific (economical) differences may be the reason for these heterogeneities. In an Italian real‐life experience, telemedicine resulted being a valuable tool in pediatric allergy and immunology practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 10 Conversely, relevant historical information obtained (as well as diagnostic procedures) may be limited by replacing in‐person consultations with telemedicine measures. As outlined above, the triage and prioritization of services and procedures provided to allergic patients may be ensured by telemedicine measures, but a better‐defined algorithm for key questions adapted for this remote consultations is needed.

The second domain of the questionnaires investigated AIT treatment in patients without any current symptoms to suspect a COVID‐19 infection. In an Italian real‐life experience regarding pediatric patients, only those with the first clinical evaluation of severe allergic reactions, uncontrolled allergic respiratory diseases and the ones receiving venom immunotherapy (VIT), vaccines in general or biologic treatments (if not possible by a local center or at home) followed the regular schedule of face‐to‐face care. 10

Remarkably almost 60% of the respondents indicated to postpone the initiation of SCIT to a time point after the pandemic (Table 2). On the other side, this fact was reported in only 35% in SLIT. The consensus report of North American experts recommends not to initiate AIT in allergic rhinitis unless there exist “unusual circumstances, such as a patient with unavoidable exposure to a trigger that has resulted in anaphylaxis or asthma”. 8 The EAACI/ARIA guidance recommends that “AIT can also be started or continued as usual in patients without clinical symptoms and signs of COVID‐19 or other infections and without a history of exposure to SARS‐CoV‐2 or contact to COVID‐19 confirmed individuals within the past 14 day”. 23 However, our analysis has revealed that only one tenth of the prescribing physicians initiated SCIT as it would be planned under regular circumstances, whereas in SLIT this was decided by almost every second prescriber. One possible reason for the latter could be that physicians may trust more in the general safety of SLIT than SCIT especially in the initiation phase of treatment. This fact is also mirrored in 16% of physicians switching the application route from SCIT to SLIT (Table 2). However, a reduction of the initiation for both application forms alerts the general risk of relevant undertreatment of allergic patients not receiving AIT as the only available treatment option with disease‐modifying potential. 26 , 28 , 47 As a high number of patients will not receive this treatment, though clearly indicated, they may lose the interest in the initiation of AIT after the end of the current pandemic. Besides, vaccines will be out of shelf life hereafter.

This alerting problem holds especially true for the treatment of venom allergic patients. For this group of patients with a potentially life‐threatening allergy, AIT with venom—as planned under regular circumstances—is only offered by almost 25% of the respondents (Table 2). Moreover, almost 40% of the respondents decided to pause this treatment and postpone the begin to a time point after the current pandemic. The underlying background can only be speculated: one reason may be the need for in‐person consultations in the practice/clinic to receive the injections. AIT for venom allergy is the most effective treatment for patients with venom allergies with much evidence supporting this treatment 30 and the consensus statement of North American experts strictly recommends the initiation of SCIT in venom allergic patients as an “essential service”. 8

However, the undertreatment revealed by this analysis undoubtedly may have increased the risk of patients during the recent summer to develop life‐threatening reactions after an insect sting. Future evaluation of anaphylaxis cases, for example, in national and international anaphylaxis registries may reveal this deficit of optimal, guideline‐conform care of patients with this life‐threatening disease. 48 Krishna et al 49 reported a significant reduction in VIT initiation in a study involving 99 Adult and Pediatric Allergy and Immunology centers in the UK National Health Service. Another survey among allergy departments in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland revealed a 48.5% decrease in the newly prescribed VIT from March–June 2019 to March–June 2020 period. 50 A real‐life experience in a Portuguese reference center revealed a marked reduction in inhalants SCIT administration (initiation suspended in 100%) with only a 2.8% continued at primary care units. 51 Nevertheless, 90% of patients continued with VIT administration with none being initiated. In a Turkish survey, 31% discontinued SCIT during the pandemic with 72% being administered with longer intervals. 52

The potential risk to patients due to undertreatment of non‐COVID‐19 diseases has also been recently demonstrated in other indications such as heart failure. 53 This analysis of the Danish nationwide administrative database revealed that the number of patients hospitalized with heart failures decreased after the lockdown in 2020 and the authors concluded that this current temporary undertreatment might indeed impact the morbidity in the future. Another web‐based survey found a negative impact of the current pandemic on rheumatology practice which may lead to suboptimal control of the disease in the near future. 54

A promising result of the analysis refers to the fact that during the maintenance phase of AIT, most physicians decided to continue SCIT as planned or with slight amendments to the treatment schedules as suggested in international position papers (Figure 2). 8 , 23 Also for venom allergic patients, SCIT should not be suspended especially in potentially life‐threatening conditions such as insect venom allergy in international recommendations. 8 , 14 , 43 Furthermore, German guidance clearly emphasized that postponing initiation during the summer season is not advised and should be avoided to reduce the risk of severe reaction to an accidental sting. 50 In addition, almost 90% of the respondents in our survey decided to continue SLIT treatment as planned with a minority of those deciding a dose reduction (Figure 2). In this regard, the prescribing physicians have followed the European recommendations not to interrupt AIT in the maintenance period of AIT in healthy patients without clinical signs of a COVID‐19. 23

During the induction phase, a low number of significant adverse events were reported for SCIT (4%) and SLIT (6%) in healthy patients and even less in the maintenance phase of AIT (Table 3). Taken together, these analyses support data from clinical trials and real‐world evidence regarding the safety of AIT in principle when treatment strategies are compliant with international guidelines in AIT. 28 , 35 A systematic meta‐analysis of the EAACI demonstrated a comparable safety profile for both application forms of AIT, but could not differentiate between the initial induction and maintenance phase. 55 Also, to the non‐interventional nature of the retrospective analysis reported here, this survey was not able to classify adverse events in international, standardized gradings. However, it can be concluded that the data set did not indicate a signal for diminished safety of AIT during the current pandemic, in patients without clinical signs of COVID‐19 or positive test results of SARS‐CoV‐2.

The third domain of the questionnaires investigated the safety of AIT in patients despite (early) symptoms of COVID‐19. In the EAACI Position Paper, 23 as well as in the German adaption, 43 AIT temporary discontinuation of both SCIT and SLIT is recommended in these patients. Also, in this scenario a consensus statement of the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology indicated immediate interruption of AIT. 14 The same is recommended in an Asian article by Lee et al, 56 stating that AIT should not be re‐administered until complete resolution of infection or test results are negative. The majority of respondents in our survey followed these recommendations as common rules (Table 4). Interestingly, those respondents informing that AIT was not interrupted have indeed not flagged‐up a significant increase of adverse events in this subset of patients with a potential for an increased risk (Table 5). For SLIT‐treated patients, none of the 14 respondents reported the onset of adverse reactions at all. For SCIT‐treated patients, only 1 responded having experienced a notable adverse event. Clinical reports of the safety of AIT under a current viral infection are scarce in general. In a comprehensive article, the limited literature of AIT in HIV patients with allergic diseases has been reviewed and found a lack of sufficient evidence for or against the application of AIT in HIV patients and further investigations collaborated by allergists together with HIV experts has been requested. 57 In one trial, clinical effects and safety of SLIT with grass tablets have been investigated in 13 HIV‐positive and grass pollen‐allergic patients with current antiretroviral therapy (HAART). 37 The clinical outcomes for allergic symptoms and quality of life improved significantly compared with nine control patients, whereas no alteration of HIV viral load or CD4‐positive T cells was found. Besides SLIT in these patients demonstrated to be safe and well tolerated. In another prospective study, the effect of an influenza virus infection on standard immunological parameters during one year course of SCIT in asthmatic patients was investigated. 58 The authors found that the presence of influenza‐like symptoms during SCIT had not affected standard biochemical and hematological parameters (eg, eosinophil and neutrophil counts, total IgE).

Our survey closed with an outlook for the second half of 2020 with the perception of a second wave of the pandemic leading to subsequent lockdown scenario (Figure 3). 77% of the respondents completely or strongly disagreed that AIT should not be performed which underlines their positive experience on the feasibility of AIT during the first wave in the first half of the year. However, almost 50% of the respondents have expressed a strong or complete agreement that AIT should only be performed in very specialized centers. This opinion may be due to uncertainity about the safety of AIT in the current pandemic in general and gives a rationale for further investigations as the one presented in this EAACI survey report.

5. CONCLUSION

The current COVID‐19 pandemic significantly affects global health systems and different medical disciplines. Allergic diseases are highly prevalent and there is a critical need for optimizing care of allergic patients during the pandemic by understanding the barriers and facilitators of allergists in the clinical routine. This is especially important in AIT as the only available disease‐modifying treatment option in allergic patients by actively modulating the immune system.

The current report presents the results of the first international retrospective survey in allergic diseases responded by over 400 prescribers of AIT from 7 July to 28 July 2020. The EAACI initiative aimed to investigate practical aspects and tolerability of AIT in daily routine during the COVID‐19 pandemic in different regions of the world.

As for other diseases, this survey's data indicate a high grade of undertreatment for SCIT, venom AIT, and SLIT which may result in a long‐lasting negative impact on allergic patients’ clinical care. Besides no tolerability concern arises from this preliminary analysis indicating AIT to be safe when compliant with international evidence‐based guidelines and well‐established treatment algorithms. The results should help improving future guidance regarding AIT management in a pandemic scenario.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Pfaar reports grants and personal fees from ALK‐Abelló, grants and personal fees from Allergopharma, grants and personal fees from Stallergenes Greer, grants and personal fees from HAL Allergy Holding B.V./HAL Allergie GmbH, grants and personal fees from Bencard Allergie GmbH/Allergy Therapeutics, grants and personal fees from Lofarma, grants from Biomay, grants from Circassia, grants and personal fees from ASIT Biotech Tools S.A., grants and personal fees from Laboratorios LETI/LETI Pharma, personal fees from MEDA Pharma/MYLAN, grants and personal fees from Anergis S.A., personal fees from Mobile Chamber Experts (a GA2LEN Partner), personal fees from Indoor Biotechnologies, grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Astellas Pharma Global, personal fees from EUFOREA, personal fees from ROXALL Medizin, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Sanofi‐Aventis and Sanofi‐Genzyme, personal fees from Med Update Europe GmbH, personal fees from streamedup! GmbH, grants from Pohl‐Boskamp, grants from Inmunotek S.L., personal fees from John Wiley and Sons AS, personal fees from Paul‐Martini‐Stiftung (PMS), all outside the submitted work. Dr. Brough discloses personal speaker fees from DBV Technologies and Sanofi outside of the submitted work. Dr. Ollert reports personal fees from Hycor Biomedical, other from Tolerogenics SarL, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Ollert has a patent WO2019/076478Al pending, and a patent WO2019/076477Al pending. Dr. Palomares reports research grants from Inmunotek S.L., Novartis and MINECO. Dr. Palomares has received fees for giving scientific lectures or participation in Advisory Boards from Allergy Therapeutics, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Diater, GlaxoSmithKline, S.A, Inmunotek S.L, Novartis, Sanofi‐Genzyme and Stallergenes. Dr. Schwarze reports personal fees from MYLAN, outside the submitted work; and as EAACI Secretary General involved in acquisition of industrial sponsorship as listed on EAACI website. Dr. Chaker reports grants for clinical studies and research and other from Allergopharma, ALK Abello, AstraZeneca, Bencard / Allergen Therapeutics, ASIT Biotech, Immunotek, Lofarma, GSK, Novartis, LETI, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Zeller and from the European Institute of Technology (EIT); has received travel support from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) and DGAKI, all outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Chaker has a patent A ratio of immune cells as prognostic indicator of therapeutic success in allergen‐specific immunotherapy: 17 177 681.8 not licensed at present. Dr. Heffler reports personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Circassia, personal fees from Stallergenes Greer, personal fees from Nestlè Purina, outside the submitted work. Dr. Quecchia reports personal fees from Stallergenes Greer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Agache reports Associate Editor Allergy and PAI. Dr. Radoslaw reports and personal fees from Allergopharma, HAL Allergy, ALK‐Abello. Dr. Jensen‐Jarolim reports other from Biomedical Int. R + D, Vienna, grants, personal fees and other from Bencard Allergie, Germany, other from AllergyTherapeutics, UK, personal fees and other from Vifor Pharma, personal fees from Meda Pharma, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Dr. Schär, outside the submitted work. Dr. Jutel reports personal fees from ALK‐Abello, personal fees from Allergopharma, personal fees from Stallergenes, personal fees from Anergis, personal fees from Allergy Therapeutics, personal fees from Circassia, personal fees from Leti, personal fees from Biomay, personal fees from HAL, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Astra‐Zeneka, personal fees from GSK, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Vectura, personal fees from UCB, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Medimmune, personal fees from Chiesi, outside the submitted work. Dr. Klimek reports grants and personal fees from Allergopharma, grants and personal fees from MEDA/Mylan, personal fees from HAL Allergie, personal fees from ALK Abelló, grants and personal fees from LETI Pharma, grants and personal fees from Stallergenes, grants from Quintiles, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, grants from ASIT biotech, grants from Lofarma, personal fees from Allergy Therapeut., grants from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from GSK, grants from Inmunotek, personal fees from Cassella med, personal fees from Novartis, outside the submitted work; and Membership: AeDA, DGHNO, Deutsche Akademie für Allergologie und klinische Immunologie, HNO‐BV, GPA, EAACI. Dr. Torres reports personal fees from Diater, Aimmune Therapeutics and Leti laboratories, grants from European Commission, MINECO and ISCIII of Spanish Government and SEAIC, outside the submitted work. Dr. Bonini, Dr. Chivato, Dr. Del Giacco, Dr. Gawlik, Dr. Gelincik, Dr. Hoffmann‐Sommergruber, Dr. Knol, Dr. Lauerma, Dr. O’Mahony, Dr. Mortz, Dr. Riggioni, Dr. Skypala, Dr. Untersmayr, Dr. Walusiak‐Skorupa, Dr. Giovannini, Dr. Sandoval‐Ruballos, Dr. Sahiner, Dr. Tomić Spirić, Dr. Alvaro‐Lozano have nothing to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The corresponding author (OP), together with Montserrat Alvaro‐Lozano (MAL) and the EAACI Immunotherapy Interest group members, elaborated the questionnaire which was then formally approved by the leadership of the EAACI. OP and MAL analyzed the data and provided a first draft of this report. Hereafter, all coauthors reviewed and amended the report where applicable and gave final approval for submission.

Supporting information

Table S1‐S3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the EAACI for funding. Moreover, they express their gratitude to Ana Antunes and Charlie Bonnet des Tuves, to all staff members of the EAACI headquarters and to all physicians and allied health professionals who kindly supported the survey and shared their valuable experience during the pandemic.

Funding information

This survey has been funded by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI)

REFERENCES

- 1. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020;382(13):1199‐1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coronavirus disease (COVID‐2019) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/situation‐reports. Accessed 13 January 2021.

- 3. Dong X, Cao Y‐Y, Lu X‐X, et al. Eleven faces of coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy 2020;75(7):1699‐1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sokolowska M, Lukasik ZM, Agache I, et al. Immunology of COVID‐19: mechanisms, clinical outcome, diagnostics, and perspectives‐a report of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). Allergy 2020;75(10):2445‐2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID‐19. JAMA 2020;323(14):1406‐1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323(13):1239‐1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riggioni C, Comberiati P, Giovannini M, et al. A compendium answering 150 questions on COVID‐19 and SARS‐CoV‐2. Allergy 2020;75(10):2503‐2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaker MS, Oppenheimer J, Grayson M, et al. COVID‐19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(5):1477‐1488 e1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pfaar O, Klimek L, Jutel M, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic: practical considerations on the organization of an allergy clinic – an EAACI/ARIA Position Paper. Allergy 2021;76(3):648‐676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giovannini M, Lodi L, Sarti L, et al. Pediatric allergy and immunology practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy: perspectives, challenges, and opportunities. Front Pediatr 2020;8:565039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person‐to‐person transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2020;395(10242):1973‐1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Guidance for wearing and removing personal protective equipment in healthcare settings for the care of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/guidance-wearing-and-removing-personal-protective-equipment-healthcare-settings (2020). Accessed 18 December 2020.

- 13. Malipiero G, Paoletti G, Puggioni F, et al. An academic allergy unit during COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;146(1):227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cardinale F, Ciprandi G, Barberi S, et al. Consensus statement of the Italian society of pediatric allergy and immunology for the pragmatic management of children and adolescents with allergic or immunological diseases during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ital J Pediatr 2020;46(1):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kahwash BM, Deshpande DR, Guo C, Panganiban CM, Wangberg H, Craig TJ. Allergy/immunology trainee experiences during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: AAAAI Work Group Report of the Fellows‐in‐Training Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9(1):1‐6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Portnoy J, Waller M, Elliott T. Telemedicine in the Era of COVID‐19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(5):1489‐1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matricardi PM, Dramburg S, Alvarez‐Perea A, et al. The role of mobile health technologies in allergy care: an EAACI position paper. Allergy 2020;75(2):259‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elliott T, Shih J, Dinakar C, Portnoy J, Fineman S. American college of allergy, asthma & immunology position paper on the use of telemedicine for allergists. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;119(6):512‐517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keswani A, Brooks JP, Khoury P. The future of telehealth in allergy and immunology training. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(7):2135‐2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lanier K, Kuruvilla M, Shih J. Patient satisfaction and utilization of telemedicine services in allergy: an institutional survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9(1):484‐486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bousquet J, Jutel M, Akdis CA, et al. ARIA‐EAACI statement on asthma and COVID‐19 (June 2, 2020). Allergy 2021;76(3):689‐697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vultaggio A, Agache I, Akdis CA, et al. Considerations on biologicals for patients with allergic disease in times of the COVID‐19 pandemic: an EAACI statement. Allergy 2020;75(11):2764‐2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klimek L, Jutel M, Akdis C, et al. Handling of allergen immunotherapy in the COVID‐19 pandemic: an ARIA‐EAACI statement. Allergy 2020;75(7):1546‐1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. EAACI . COVID‐19 reports in allergy. 2020. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/toc/10.1111/(ISSN)1398-9995.COVID-19. Accessed 9 December 2020.

- 25. Pfaar O, Torres MJ, Akdis CA. COVID‐19: a series of important recent clinical and laboratory reports in immunology and pathogenesis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and care of allergy patients. Allergy 2021;76(3):622‐625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jutel M, Agache I, Bonini S, et al. International consensus on allergy immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136(3):556‐568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pfaar O, Agache I, Blay F, et al. Perspectives in allergen immunotherapy: 2019 and beyond. Allergy 2019;74(Suppl 108):3‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roberts G, Pfaar O, Akdis CA, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Allergy 2018;73(4):765‐798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Halken S, Larenas‐Linnemann D, Roberts G, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: prevention of allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017;28(8):728‐745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sturm GJ, Varga E‐M, Roberts G, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy 2018;73(4):744‐764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muraro A, Roberts G, Halken S, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: executive statement. Allergy 2018;73(4):739‐743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alvaro‐Lozano M, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. Allergen immunotherapy in children user's guide. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2020;31(Suppl 25):1‐101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pfaar O, Angier E, Muraro A, Halken S, Roberts G. Algorithms in allergen immunotherapy in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Allergy 2020;75(9):2411‐2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shamji MH, Kappen JH, Akdis M, et al. Biomarkers for monitoring clinical efficacy of allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergic asthma: an EAACI Position Paper. Allergy 2017;72(8):1156‐1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pitsios C, Demoly P, Bilò MB, et al. Clinical contraindications to allergen immunotherapy: an EAACI position paper. Allergy 2015;70(8):897‐909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Balekian DS, Banerji A, Blumenthal KG, Camargo CA Jr, Long AA. Allergen immunotherapy: no evidence of infectious risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137(6):1887‐1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iemoli E, Borgonovo L, Fusi A, et al. Sublingual allergen immunotherapy in HIV‐positive patients. Allergy 2016;71(3):412‐415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. SurveyMonkey Website. http://www.surveymonkey.com. Accessed 9 December 2020.

- 39. Mateen FJ, Rezaei S, Alakel N, Gazdag B, Kumar AR, Vogel A. Impact of COVID‐19 on U.S. and Canadian neurologists’ therapeutic approach to multiple sclerosis: a survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices. J Neurol 2020;267(12):3467‐3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paffenholz P, Peine A, Fischer N, et al. Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on urologists in Germany. Eur Urol Focus 2020;6(5):1111‐1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peine A, Paffenholz P, Hellmich M, et al. [Perception of the COVID‐19 pandemic among pneumology professionals in Germany]. Pneumologie 2020. 10.1055/a-1240-5998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Paffenholz P, Peine A, Hellmich M, et al. Perception of the 2020 SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic among medical professionals in Germany: results from a nationwide online survey. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9(1):1590‐1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klimek L, Pfaar O, Worm M, et al. Allergen immunotherapy in the current COVID‐19 pandemic: A position paper of AeDA, ARIA, EAACI, DGAKI and GPA: Position paper of the German ARIA Group(A) in cooperation with the Austrian ARIA Group(B), the Swiss ARIA Group(C), German Society for Applied Allergology (AEDA)(D), German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI)(E), Society for Pediatric Allergology (GPA)(F) in cooperation with AG Clinical Immunology, Allergology and Environmental Medicine of the DGHNO‐KHC(G) and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI)(H). Allergol Select 2020;4:44‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pfaar O, Klimek L, Worm M, et al. Handling of allergen immunotherapy in the COVID‐19 pandemic: an ARIA‐EAACI‐AeDA‐GPA‐DGAKI Position Paper (Pocket‐Guide). Laryngorhinootologie 2020;99(10):676‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. German Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (DGAI) . Survey COVID‐19 and AIT. https://dgaki.de/hier‐zur‐umfrage‐zu‐covid‐19‐und‐ait/. Accessed 9 December, 2020.

- 46. Waibel KH, Bickel RA, Brown T. Outcomes from a regional synchronous tele‐allergy service. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7(3):1017‐1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pfaar O, Bachert C, Bufe A, et al. Guideline on allergen‐specific immunotherapy in IgE‐mediated allergic diseases: S2k Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Society for Pediatric Allergy and Environmental Medicine (GPA), the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), the Austrian Society for Allergy and Immunology (OGAI), the Swiss Society for Allergy and Immunology (SGAI), the German Society of Dermatology (DDG), the German Society of Oto‐ Rhino‐Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (DGHNO‐KHC), the German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ), the Society for Pediatric Pneumology (GPP), the German Respiratory Society (DGP), the German Association of ENT Surgeons (BV‐HNO), the Professional Federation of Paediatricians and Youth Doctors (BVKJ), the Federal Association of Pulmonologists (BDP) and the German Dermatologists Association (BVDD). Allergo J Int 2014;23(8):282‐319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Worm M, Francuzik W, Renaudin J‐M, et al. Factors increasing the risk for a severe reaction in anaphylaxis: an analysis of data from The European Anaphylaxis Registry. Allergy 2018;73(6):1322‐1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krishna MT, Beck S, Gribbin N, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on adult and pediatric allergy & immunology services in the UK national health service. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9(2):709‐722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Worm M, Ballmer‐Weber B, Brehler R, et al. Healthcare provision for insect venom allergy patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Allergo J Int 2020;29(8):257‐261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carneiro‐Leao L, Amaral L, Coimbra A, Placido JL. Real‐life experience of an allergy and clinical immunology department in a Portuguese reference COVID‐19 hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(10):3671‐3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ozturk AB, Baccioglu A, Soyer O, Civelek E, Sekerel BE, Bavbek S. Change in allergy practice during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2021;182(1):49‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Andersson C, Gerds T, Fosbøl E, et al. Incidence of new‐onset and worsening heart failure before and after the COVID‐19 epidemic lockdown in Denmark: a nationwide cohort study. Circ Heart Fail 2020;13(6):e007274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ziadé N, Hmamouchi I, el Kibbi L, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on rheumatology practice: a cross‐sectional multinational study. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39(11):3205‐3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dhami S, Nurmatov U, Arasi S, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy 2017;72(11):1597‐1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee J‐H, Lee Y, Lee S‐Y, et al. Management of allergic patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Asia. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2020;12(5):783‐791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alam S, Calderon M. Safety and efficacy of allergen immunotherapy in patients with HIV and allergic rhinitis: facts and fiction. Curr Treat Options Allergy 2015;2:32‐38. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ahmetaj L, Mehic B, Gojak R, Neziri A. The effect of viral infections and allergic inflammation in asthmatic patients on immunotherapy. Turkish J Immunol 2018;6(3):123‐130. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1‐S3