Abstract

This paper presents new high‐frequency data on trade policy changes targeting medical and food products since the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic, documenting how countries used trade policy instruments in response to the health crisis on a week‐by‐week basis. The data set reveals a rapid increase in trade policy activism in February and March 2020 in tandem with the rise in COVID‐19 cases but also uncovers extensive heterogeneity across countries in both their use of trade policy and the types of measures used. Some countries acted to restrict exports and facilitate imports, others targeted only one of these margins, and many did not use trade policy at all. The observed heterogeneity suggests numerous research questions on the drivers of trade policy responses to COVID‐19, on the effects of these measures on trade and prices of critical products, and on the role of trade agreements in influencing the use of trade policy.

Keywords: COVID‐19, export restrictions, import liberalisation, trade policy

1. INTRODUCTION

One of the instruments many governments resorted to in responding to the COVID‐19 pandemic was trade policy. Barriers to the importation of medical products and supplies and agricultural and food products were lowered, and restrictions imposed on exports of such goods. The mix of import facilitation and export controls were driven by the objective of maximising the availability of critical supplies in the domestic market. Real‐time tracking of the use of trade policy measures is difficult as governments only report changes in trade policy to the WTO with a lag and may not notify the WTO at all. Timely information on trade policy measures matters for businesses seeking to expand production and needing to source inputs to do so, to public authorities responsible for procuring critical supplies, and for policy analysts interested in assessing the effects and effectiveness of policy responses to the pandemic.

This paper introduces a new data set on trade policy interventions—both to control exports and facilitate imports of food, medical supplies and personal protective equipment (PPE). The data set is the product of an ongoing open data initiative conducted by the Global Trade Alert (GTA) in partnership with the European University Institute and the World Bank to collect information on changes in trade policy towards exports and imports of medical and food products starting in January 2020.1 Until mid‐October 2020 the data were collected and reported on a weekly basis, providing the ability to track the imposition and removal of measures across a wide range of countries. The high‐frequency of the data is a unique feature of the exercise. The project is ongoing. The data used in this paper span the period from 2 January 2020 to 9 October 2020.

Our aim in this paper is to provide a descriptive assessment of the trade policy measures implemented in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. This paper and the accompanying database complement a growing body of policy‐oriented economic research studying international trade during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Early in the pandemic many analysts and organisations stressed the importance of keeping borders open to allow supply chains to work efficiently in ramping up supply of critical products (e.g. Baldwin & Evenett, 2020; Bown, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c; Evenett, 2020; Espitia et al., 2020a, 2020b; Mattoo & Ruta, 2020; OECD, 2020; WTO, 2020). In practice, some countries did so; others did not. Understanding the drivers of the differences in observed trade policy responses over time and across countries and sectors is important for drawing inferences (and lessons) about the implications of the COVID‐19 pandemic for international cooperation and potential rule‐making looking forward. The data set allows empirical analysis of a range of research questions. We provide some illustrative examples in the penultimate section of this paper, but we do not undertake such analyses here. Instead, our main aim is to raise awareness of the data set in the hope others will be encouraged to use it.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the data set and provides basic summary statistics. Section 3 highlights some stylised facts that emerge from the trade policy responses to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Section 4 discusses several hypotheses suggested by these stylised facts and possible research questions that could be the subject of further analysis. Section 5 concludes.

2. THE DATA SET

The data collection initiative presented in this paper is confined to trade policy changes in two sectors: medical goods and medicines, and agricultural and food products. The products falling under each of these sectoral headings are listed in the methodology note that accompanies the database.2 Policy interventions by national and sub‐national governments, as well as actions taken at the supra‐national level by a customs union, are included in the data collection exercise.

Trade policy measures are identified by the GTA team using the following methodology. First, automated techniques are used to gather information in multiple languages on relevant trade policy changes from many different sources including websites of relevant government agencies (which can include finance ministries, trade ministries, customs agencies, health ministries or associated agencies, and offices of the head of government or state); websites of relevant international organisations (IMF, ITC, UNCTAD, WCO, WTO); online media sources, including social media; and non‐state organisations collecting information on the matters falling within the scope of this initiative, including law firms, consulting companies, research institutes and other academic initiatives.

These sources are searched for keywords in major languages relating to the policies and products falling into the two sectors of interest. Such searches create ‘leads’ which are processed to identify those that legitimately characterise a trade policy change falling within the scope of the initiative. Every lead recorded in the GTA’s systems is validated in a multi‐step analytical process. In the first step, an analyst uses a standard template to sort through ‘leads” that have been captured through the process described above and provides an initial assessment of whether the lead is of topical relevance (within scope as defined in the last section), the implementing jurisdiction, the policy instrument category described, the product categories affected, and the direction of the trade policy change. This initial assessment is subsequently validated by a second analyst who confirms, amends or rejects the first's choices. Once past this initial assessment, relevant leads then move into the GTA reporting pipeline. Where missing in the first step, an official source is sought and, if found, saved for each lead. Once the official source has been located, the responsible GTA trade policy analyst processes the lead into a GTA database entry that combines a brief description of the state act along with identification of the most accurate policy instrument among a rich taxonomy plus the appropriate United Nations product and sectoral codes.3 All entries are checked by a senior team member before inclusion in the data set.

The final database on trade policy changes includes information on the sector affected (medical products and/or food); the type of information used to document the trade policy change (official source, report on the Global Trade Alert website, media sources, or consultancy or law firm reports); the jurisdiction implementing the trade policy change; an initial assessment whether the trade policy change is liberalising or restrictive; where relevant/available the date the trade policy change was announced/was implemented and lapsed; and whether the trade policy change affects imports and/or exports.

The version of the data set used in this paper spans the period up to 9 October 2020.4 It includes 701 policy measures covering 135 customs territories (the European Union, the South African Custom Union, and the Eurasian Custom Union are considered as a single territory, independent from their Member States).5 For the ensuing descriptive analysis of trade policy measures across countries and over time, we consider the date of announcement as the starting date of each measure. We clean the data accordingly to remove inconsistencies in the reported measures. We also exclude measures with a 2019 announcement date, that is, before the COVID‐19 outbreak. This leaves 645 measures, of which 284 have no removal date indicated and 52 are to be removed in 2021 or later.

The discussion that follows focuses on two types of measures: export restrictions and import liberalisation‐cum‐facilitation. These cover most of the measures in the data set. Details on the set of policy instruments included in these two categories are reported in Appendix Table A1.6 The data set encompasses significantly more measures than reported by the two international organisations that have engaged in monitoring exercises. The first of these is the International Trade Centre (ITC), which launched a COVID‐19 dashboard in early 2020 that provides information on trade measures taken by countries. The focus of this is not limited to food and medical products. As of 9 October 2020, the ITC repository comprised 338 measures implemented by 145 countries, custom unions and autonomous territories, substantially fewer than reported by the GTA.7

The second is the WTO, which reports on COVID‐19 related measures notified by its members and maintains a separate data set on export and import‐related measures compiled by the WTO Secretariat on its own initiative that is drawn from official sources. The latter includes only measures that are verified by the WTO members concerned. Transparency is a fundamental dimension of WTO membership. This also applies to emergency measures. WTO members must notify quantitative restrictions that are motivated by domestic emergencies, including public health. The relevant 2012 Decision on Notification Procedures for Quantitative Restrictions (WTO G/L/59/Rev.1) stipulates that notifications must occur at two yearly intervals, and more salient to the present context, report changes as soon as possible, and no later than six months from their entry into force (Hoekman, 2020).8 WTO members may engage in so‐called reverse notifications as well, reporting on measures imposed by other countries and customs territories.

In principle, transparency through notification and reverse notification supports discussion in the WTO of measures taken. In practice, many WTO members have not lived up to their transparency obligations, notwithstanding commitments by G20 Trade Ministers to notify the WTO of trade‐related measures taken. As of 9 October 2020, 55 WTO members had submitted 245 notifications related to COVID‐19. These span not only export restrictions and import liberalisation‐cum‐trade facilitation measures but also changes in product regulation (standards) and economic support (subsidy) programmes. Brazil is the leader in having notified 28 measures, followed by Kuwait (16), the USA (14), the European Union (12), Philippines (11), Thailand (11) and Korea (9) (Figure 1). Three‐quarters of these COVID‐19 related notifications pertain to product standards for medical supplies and PPE.9 Through 9 October 2020, only 58 COVID‐19 related notifications to the WTO did not pertain to sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) or technical barriers to trade (TBT). This compares to 645 measures—both export restrictions and import liberalisation/facilitation—targeting food and medical products included in the GTA data set.10 Matters are worse than suggested by these figures because some notifications by WTO members concern updates for the same measure and some pertain to support programmes, neither of which are included in the GTA COVID‐19 data set.11

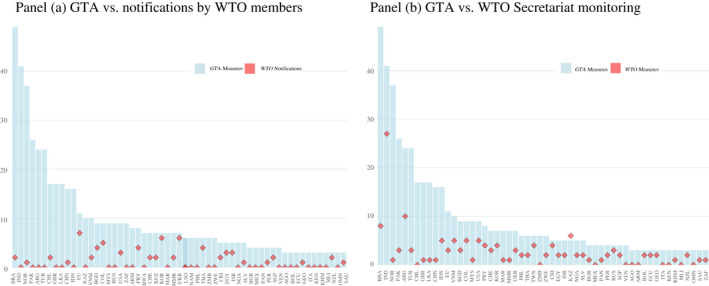

FIGURE 1.

GTA vs. WTO Monitoring. (a) GTA vs. notifications by WTO members. (b) GTA vs. WTO Secretariat monitoring.

Notes: To increase legibility, both panels only report the countries with at least 3 measures recorded in the GTA data. This leaves out half of the countries for which the GTA collected information (54 out of 109), which account for <13% of the total measure included in the GTA data.

Source: Hoekman (2020).

The differences in terms of coverage are illustrated in Figure 1. Panel (a) plots the number of non‐SPS, non‐TBT related notifications to the WTO by members (the red diamonds) against the measures picked up by the GTA. Panel (b) instead compares the data on export and import‐related measures compiled by the WTO Secretariat on its own initiative from official sources and that members have verified. This shows more overlap with the GTA data, but still reveals a significant discrepancy: through 9 October 2020, the WTO secretariat reported 243 verified measures taken by 85 member/observer states, substantially fewer than the 645 found by the GTA.12

3. COVID‐19 TRADE POLICY RESPONSES ACROSS COUNTRIES AND TIME

In this section, we discuss some of the stylised facts emerging from the data on use of export restrictions and import liberalisation‐cum‐facilitation measures during the first nine months of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

3.1. Food vs. Medical Products; Restrictions vs. Trade Facilitation

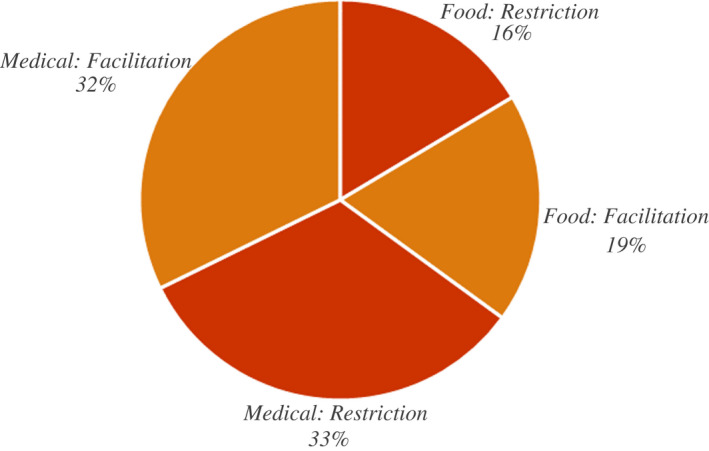

A first stylised fact is that measures targeting medical products and PPE dominate, accounting for two‐thirds of all trade measures taken. Food is less in focus. Medical sector measures are divided roughly equally between export restrictions and import facilitation. For the food sector, import liberalisation‐cum‐facilitation represents 55% of the relevant policy changes (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Export restrictions and import facilitation in food and medical products.

Note: Some 7% of the policy measures recorded by the GTA involve both Food and Medical products. These measures have been counted in both sectors.

Table 1 reports the evolution of active measures over time. Apart from medical goods in March 2020, import‐facilitating measures outnumber export restrictions. Overall, import facilitation slightly dominates the trade policy responses in every month after February 2020, for both food and medical products. Export restricting measures peak in April/May 2020, but the overall number of measures do not vary significantly during the period.

TABLE 1.

Active measures over time

| Food | Medical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Import Facilitation | Export Restrictions | Import Facilitation | Export Restrictions | |

| February | 14 | 6 | 13 | 6 |

| March | 17 | 8 | 24 | 49 |

| April | 47 | 33 | 141 | 120 |

| May | 59 | 32 | 170 | 126 |

| June | 68 | 30 | 177 | 112 |

| July | 66 | 26 | 172 | 109 |

| August | 70 | 28 | 180 | 112 |

| September | 80 | 34 | 183 | 114 |

| October | 75 | 33 | 149 | 107 |

The number of active trade policies is computed on the 15th of each month. Roughly 7% of total policies recorded by GTA involve both Food and Medical products. These measures have been counted in both sectors.

Similar patterns of relative importance across sectors and categories emerge when looking at the value of trade covered. To provide a rough estimate of such values we have used UN Comtrade data for 2019 (or latest year available) to estimate the amounts of trade which may be implicated in our data set. For inclusion into the GTA database, the products affected by each intervention are classified according to the Harmonized System (HS). We use HS codes at the 6‐digit‐level, the most granular product breakdown for which there is comparable international trade data available. To estimate the amount of trade that may be implicated by each intervention, we sum over trade flow values in the affected products in the year prior to the intervention. The estimates account for geographic restrictions on the potentially affected trading partners such as FTA exemptions or targeted interventions. Furthermore, to remove de minimis trade flows, we apply a minimum threshold of USD 1 million per HS code—trading partner combination.

In terms of the value of trade covered, trade policy changes in medical goods outweigh those in food products by a factor of 3 or higher (Table 2, panel a). At the same time, trade reforms in both product groups outweigh the newly erected barriers in our sample. We estimate that export curbs in medical goods and medicines covered international trade worth $135 billion, whereas the many import reforms in the same sector covered $165 billion of 2019 trade. In the case of food and agri‐food products, the comparable totals are $39 billion and $42 billion, respectively. The instability of trade patterns is an important caveat for the estimates presented above. Basing our estimates on trade values in medical supplies and equipment that pre‐date the COVID‐pandemic may misrepresent the scale of the potential trade coverage. Global demand for medical supplies and equipment spiked as the pandemic encompassed ever more countries. Thus, the estimates presented for these products may understate the magnitude of implicated trade flows.

TABLE 2.

Trade coverage of measures tracked by GTA database (US$ bn)

| Panel a: Annualised totals of 2019 world trade | ||

|---|---|---|

| Export restraints | Import reforms | |

| Medical | 134.6 | 165.2 |

| Food | 39.4 | 42.2 |

| Panel b: Medical goods only | |

|---|---|

| Trade‐restrictive measures | Worldwide export coverage |

| All included instruments | 134.6 |

| Of which | |

| Export ban | 101.8 |

| Export licensing requirement | 66.2 |

| Export quota | 1.4 |

| Trade liberalising measures | |

| All included instruments | 165.2 |

| Of which | |

| Import ban | 0 |

| Import licensing requirement | 6.3 |

| Import quota | 0 |

| Import‐related non‐tariff measure, nes | 7.5 |

| Import tariff | 145.7 |

| Import tariff quota | 12.5 |

| Internal taxation of imports | 88.6 |

Table 2 (panel b) disaggregates by policy measure, while Table 3 looks at the share of 2019 trade affected over time.13 The data show the importance of export bans in medical goods and tariff changes among the trade liberalising measures. In terms of the evolution of the share of trade covered over time, we observe a surge in February–March–April 2020 for both trade liberalising and restrictive measures affecting medical and food products. Thereafter, trade coverage of trade‐restrictive measures slightly declines, while coverage of liberalising measures stabilises.

TABLE 3.

Affected portion of trade over time

| Food | Medical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Import reforms (%) | Export restraints (%) | Import reforms (%) | Export restraints (%) | |

| February | 4.8 | 3.3 | 5.6 | 1.4 |

| March | 5.1 | 4.6 | 8.4 | 6.4 |

| April | 6.1 | 5.7 | 10.7 | 7.4 |

| May | 6.2 | 5.6 | 11.3 | 4.6 |

| June | 7.0 | 5.5 | 12.2 | 4.6 |

| July | 6.7 | 3.8 | 11.3 | 4.5 |

| August | 6.9 | 3.8 | 11.1 | 4.4 |

| September | 6.8 | 3.6 | 11.4 | 4.3 |

All data in Tables 2 and 3 are based on interventions in the GTA database which were implemented since 1 January 2020 and affecting at least one product from the list of essential goods (available at: https://globalgovernanceprogramme.eui.eu/wp‐content/uploads/2020/05/Methodologynote050420.pdf). Trade data from UN Comtrade for 2019 or latest year available.

3.2. Who did what for how long?

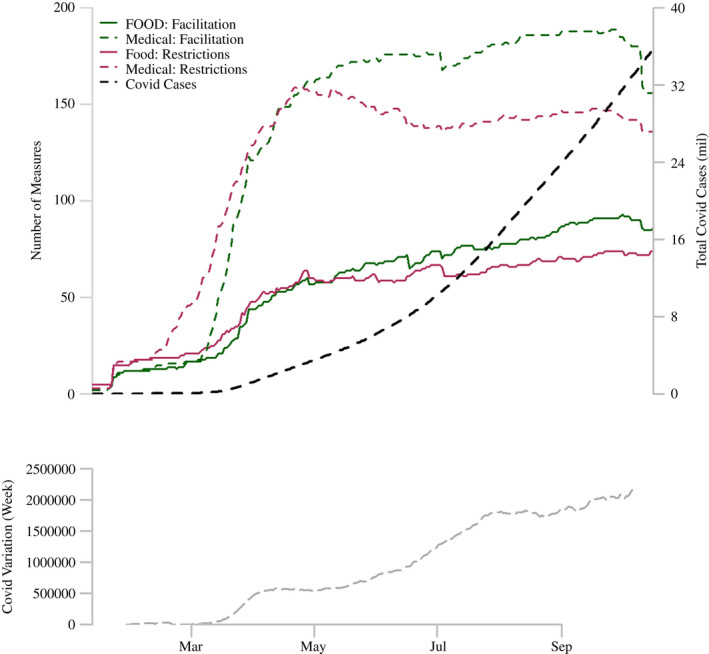

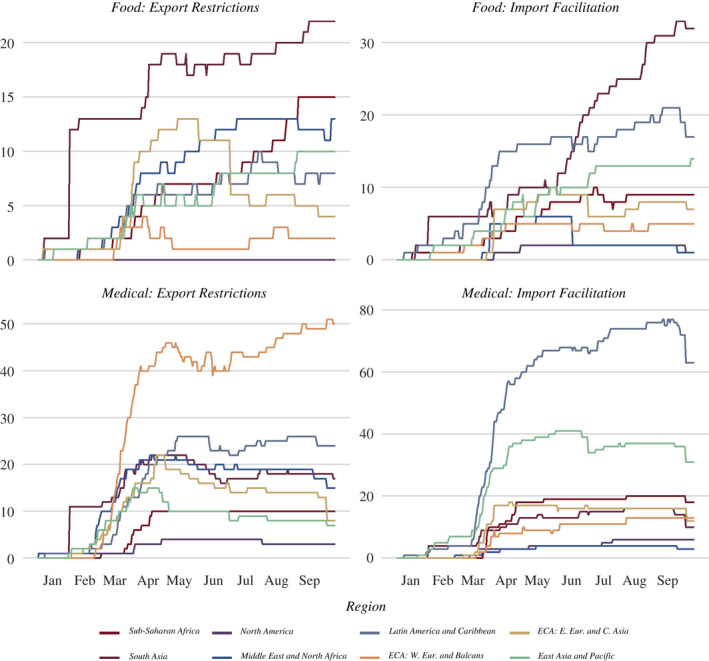

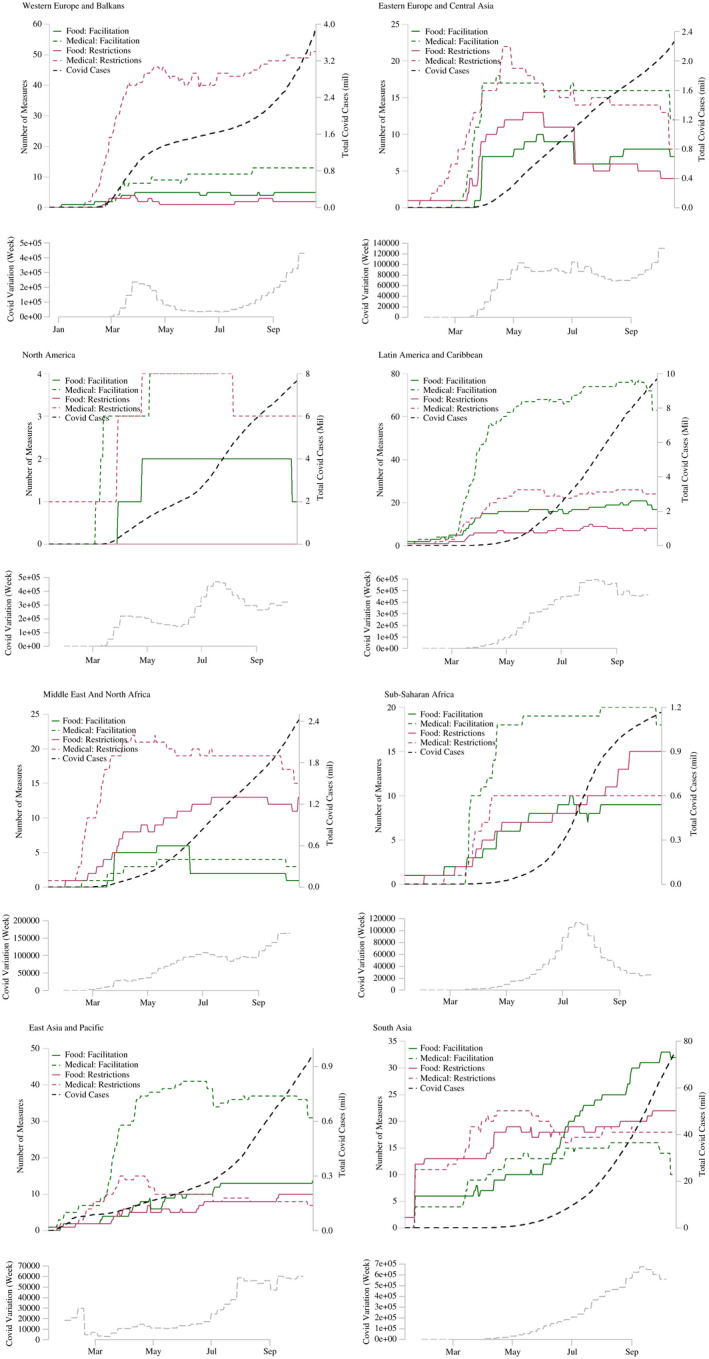

There are some clear patterns in changes to trade policies observed during the first nine months of the COVID‐19 pandemic. First, there is a big jump in trade policy activism starting in February and accelerating in March (top panel Figure 3), with the initial increase occurring in tandem with the rise in the number of COVID‐19 cases (the bottom part of Figure 3 plots the weekly change in global COVID‐19 cases).

FIGURE 3.

Global COVID‐19 Cases and Trade Policy Measures.

Notes: For each regional sub‐figure the upper part of the graph plots the number of active trade policy measures and the absolute number of COVID‐19 cases over time while the lower part plots the weekly variation in COVID‐19 cases.

Source: COVID‐19 data from the Johns Hopkins University CSSE database.

As noted previously, there is a more marked increase in the number of measures pertaining to medical products/PPE than actions targeting food products, and, for both sectors, we observe a greater number of liberalisation‐cum‐facilitation measures than trade restrictions. The latter pattern is stronger after May 2020, reflected in a gradual decline in the overall number of export control measures for medical products. Starting in August–September we also see a decline in the number of import‐facilitating measures, reflecting a partial rollback of reductions in import barriers (tariffs, taxes) for medical goods. The number of measures affecting food trade rise steadily throughout the period, with trade facilitating measures only showing a slight decline in late September/early October. The correlation between trade policies and the weekly increase in global COVID‐19 cases is high, as expected, and appears to be stronger for food‐related measures than for trade policies towards medical products (Table 4). Correlations that also consider cross‐country variation reveal greater similarity between food and medical product‐related trade policy activism.

TABLE 4.

Correlation between trade measures and number of global COVID cases

| Weekly Variation | Total Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Medical | Food | Medical | |

| Restrictions | 0.867* | 0.666* | 0.743* | 0.515* |

| Liberalisation | 0.926* | 0.806* | 0.827* | 0.657* |

p < 0.05.

Source: COVID‐19 data from John Hopkins University CSSE database.

Regional patterns (see Appendix Figure A1) confirm to some extent the timing of the aggregate (global) response, but also reveal significant heterogeneity. Countries responded to the COVID‐19 pandemic with heterogeneous timings and different combinations of export controls and import liberalisation‐cum‐trade facilitating measures. Some countries acted both on the restrictive and liberalising side, significantly changing their pre‐COVID trade policy structures; other countries acted only on one side, either restricting trade or liberalising it. Short‐term changes in trade policy were very frequent. Finally, many countries did not employ any trade policy tool during the period considered.

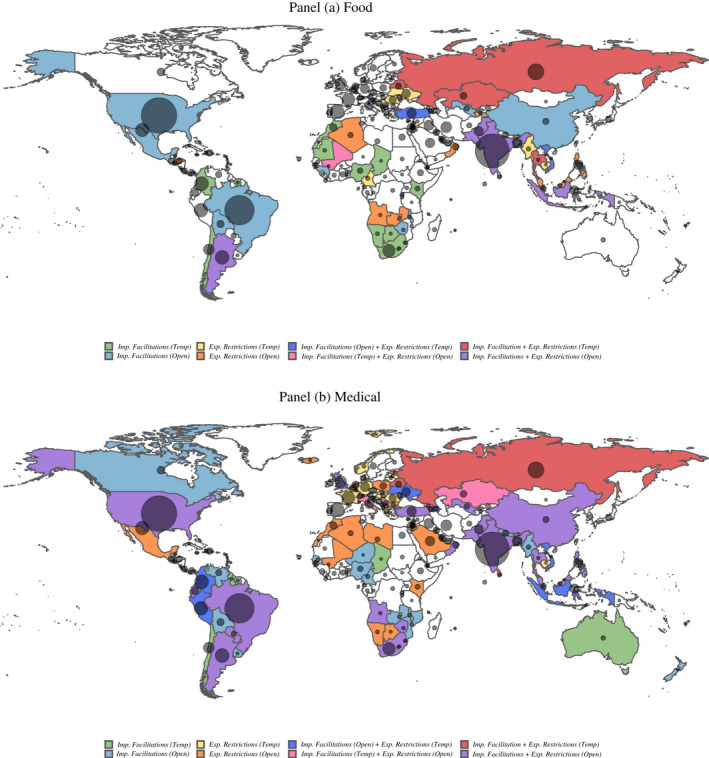

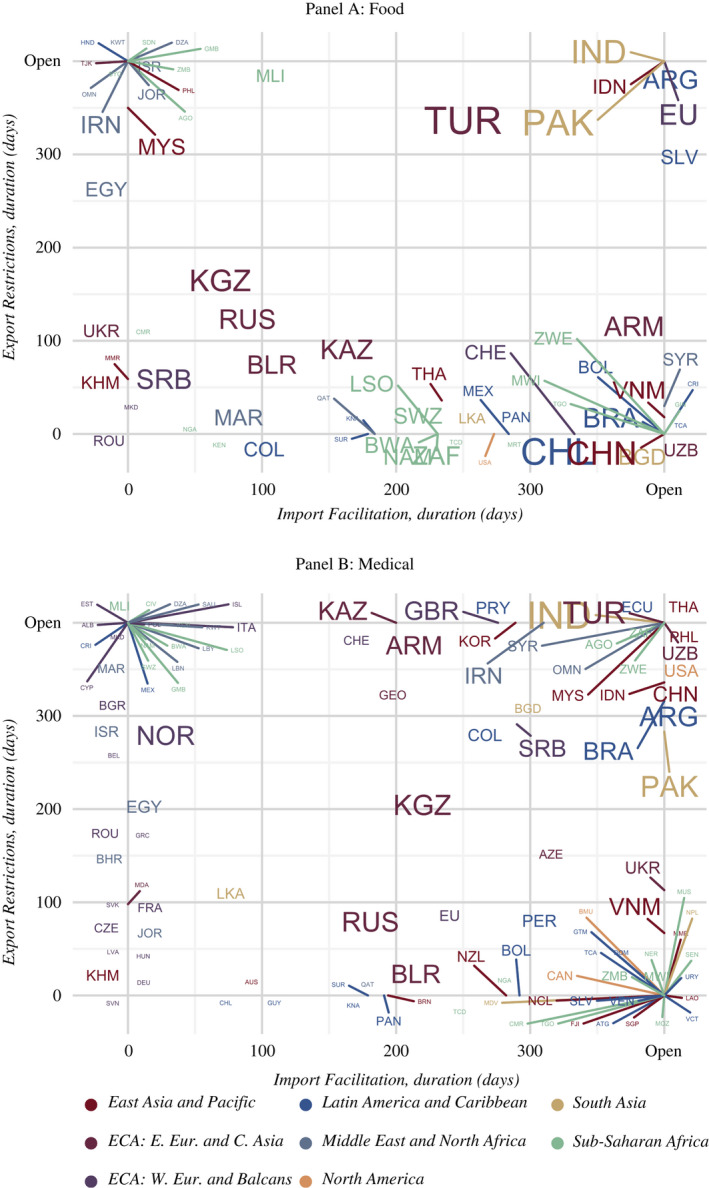

Figure 4 offers a visual representation at the country level of these different strategies by identifying countries that did not implement any change, and, for active jurisdictions, by distinguishing between explicitly temporary versus open‐ended changes. Sectoral heterogeneity emerges (again) in shaping trade policy responses across countries. The food sector (Panel (a) Figure 4) is characterised by a higher number of inactive countries (coloured white), and a higher tendency to implement temporary rather than open‐ended trade policy changes. Some major net exporters of food tended to adopt a mix of import facilitation and export restrictions. Argentina and Indonesia did so on an open‐ended basis, whereas Russia and Kazakhstan did so on a temporary basis. Other major food producers only took action to liberalise‐facilitate imports of food products (e.g. Brazil and the US). Many net importers in Africa did the same but on an explicitly temporary basis.

FIGURE 4.

Trade policy responses and COVID‐19 cases across countries. (a) Food. (b) Medical.

Notes: Blank (white) fill implies no trade measure of any type was implemented. Bubbles are representative of the absolute number of COVID‐19 cases in each country for which data were available. Data on COVID‐19 cases are sourced from The Johns Hopkins University CSSE COVID‐19 Data. All information was extracted on 9 October 2020.

Turning to trade policies towards medical products, there are again countries that took only measures to facilitate trade. Australia, Chile, New Zealand are among those that did so, as did Canada, Colombia and Thailand. In contrast, many European countries stand out by imposing measures to temporarily control exports, while other countries—Mexico, North African countries—did so on an open‐ended basis. Many countries act on both the export and import margin in an effort to enhance domestic access to (availability of) medical supplies and PPE. This is the case for several large countries, for example, Brazil, China, India, South Africa and the United States.

Figure 5 explores variation over time and across geographic regions. As far as the food sector is concerned, South Asia appears the most active region in implementating both restrictive and liberalising trade policy changes. When it comes to policies affecting medical goods, Latin America and the Caribbean had the highest number of active import liberalisations, followed by East Asia and Pacific. The Western Europe and the Balkans sub‐region shows instead the highest number of active export restrictions.

FIGURE 5.

Trade policy responses over time and across geographic regions.

Note: Number of active policies refers to the declared termination date.

A richer visualisation of the different trade policy strategies is given in Figure 6. In both panels (A for food and B for medical goods), countries are displayed in terms of the duration (in days) of the longest period in which there is at least one active import facilitation action (measured on the horizontal axis) and the duration of the longest period with at least one active export restriction (measured on the vertical axis). The value ‘Open’ at the end of each axis identifies open‐ended measures (with no end date specified) and measures with an end date that is in 2021 or later. The size of each country code displayed in the chart is proportional to the total number of trade measures implemented, while its colour identifies the associated geographic region defined in the legend at the bottom of each panel.

FIGURE 6.

Trade policy responses. Who did what for how long?

Notes: Panel A: Food. Panel B: Medical. Coloured lines point to the names of countries located in the same space of a graph. Countries are displayed in terms of the duration (in days) of the longest period with at least one active import liberalisation measure (horizontal axis) and at least one active export restriction (vertical axis). The value ‘Open’ at the end of each axis identifies measures without an end date or that extend beyond December 2020. The font size of each country code is proportional to the total number of measures implemented; colours identify the associated world region.

Figure 6 drills down further into the timing of policy changes by country/jurisdiction and highlights variation across countries in the duration of temporary interventions. Compare for instance the very short duration of German and French restrictions on medical exports (displayed on the lower part of the vertical axis in Figure 6, Panel b) with the longer duration strategy chosen by Belgium or Italy (at the upper end of the vertical axis).

Keeping the focus on European countries, Figure 6 also captures the heterogeneous responses of EU Member States with respect to each other as well as changes in the EU common commercial policy. The figure illustrates that the EU chose an open‐ended import liberalisation strategy for the food sector (see the EU label in the bottom‐right corner of Panel a). Apart from Romania (which imposed a temporary export ban), other EU Member States did not adopt any idiosyncratic measures. The picture is different for medical goods. In that sector, the strategy of the EU—temporary export restrictions (lasting less than 100 days) combined with a 6‐month‐period of sustained import facilitation—was accompanied by numerous idiosyncratic measures affecting trade at Member State level, with a common feature being that national actions complement those imposed for the EU as a whole by involving export controls and restrictions.

More broadly, Figure 6 shows how countries differ in the duration and mix of measures used for each sector. It shows that some primarily engaged in import facilitation (located at the far right of the horizontal axis); others restricted exports without facilitating imports (those located at the top of the vertical axis) and many did both, with some imposing many more measures than others (reflected in the size of the font of each country label).

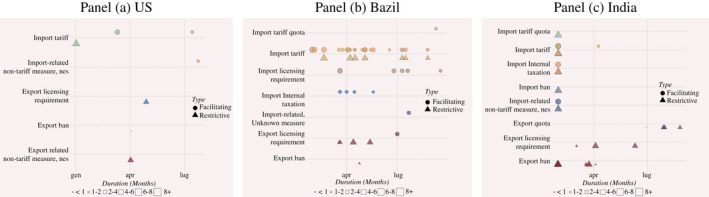

The data also allow identification of measures beyond the broad categorization of export controls and import facilitation. Appendix Figure A2 illustrates this by using all the information in the database to plot the structure of trade policy responses for medical products for three populous countries with high absolute numbers of COVID‐19 cases: Brazil, India and the United States. Comparing across the three panels it is evident that there was substantial cross‐country heterogeneity in the use of specific instruments.

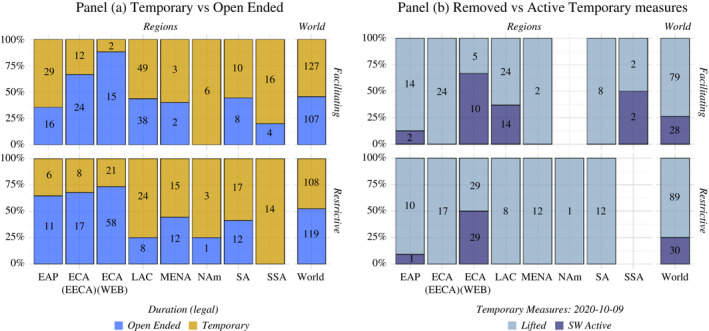

Figure 7 reports the region‐specific and global distribution of temporary versus de jure open‐ended measures (Panel a). Within the former, it also distinguishes between those that were removed during the nine‐month‐period under consideration and those that remained in place as of 9 October 2020 (Panel b).

FIGURE 7.

Medical Sector – Temporary vs. Long‐term (open‐ended) Measures. (a) Temporary vs. Open‐Ended. (b) Removed vs. Active Temporary measures.

Notes: Panel (a) reports medical‐related import liberalisation/facilitation and/or export restrictions by declared duration. Open‐ended measures include all policies for which no removal date is specified or with a duration that extends beyond 2020. Panel (b) focuses on measures that were reported as explicitly temporary with end dates in 2020, distinguishing between those that had been removed as of 9 October 2020 and those that remained to be withdrawn before the end of 2020.

At the global level, there is an approximate balance between temporary and open‐ended measures, but significant heterogeneity at the reginal level. The Western Europe and Balkans region has the highest percentage share of temporary measures (Panel a) but also the highest share of measures that were still active at the end of the period (Panel b). The East Asia and Pacific and Europe and Central Asia regions also reveal a prevalence of temporary trade policy changes, with most measures removed as of Octobers 2020. All other regions tend to use more intensively measures that are open‐ended (i.e., not explicitly time‐bound).

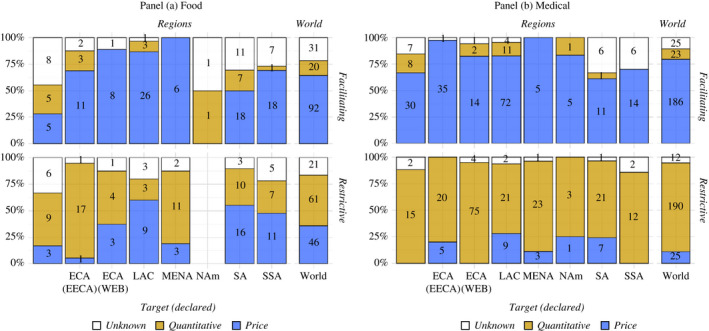

Figure 8 presents yet another dimension of heterogeneity: the degree to which jurisdictions employ price‐based (tax) measures as opposed to quantitative restrictions. Import facilitation mostly involves price‐based measures (reductions in taxes and import tariffs). The opposite is true for export controls, especially for medical products where systematically across regions more than two‐thirds of trade policy changes targeted quantities rather than prices.

FIGURE 8.

Price‐based vs. quantitative measures. (a) Food. (b) Medical.

Notes: Price targeting measures include export taxation, internal import taxation, import tariffs and tariff quotas. Quantitative measures include import/export quotas, generic non‐tariff measures, import/export bans, licensing requirements. The residual ‘Unknown’ category groups all measures with no clear description.

4. POTENTIAL AVENUES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

As mentioned, the primary purpose of this paper is to raise awareness of the COVID‐19 trade policy data set and encourage its use.14 In this section, we briefly sketch out possible research questions suggested by the patterns we observe in the data.

4.1. Policy choice

A first set of questions centre around understanding the motives underlying choices reflected in the substantial cross‐country heterogeneity observed in the data. These include the timing, duration and use of different instruments. Potential explanatory variables include mechanisms pertaining to the medical, economic and political spheres, for example, public health parameters of the COVID‐19 pandemic; features of pre‐crisis trade and trade policy structures, such as trade dependency, GVC participation and positioning; degree of existing protection; participation in multilateral or plurilateral trade policy initiatives; political forces; or factors determining the quality (effectiveness) of government action. An important corollary exercise would be to test whether and how such relationships vary between the food and medical sectors and potentially between more disaggregated product‐level categories.

Herding effects could be considered as well, calling into question whether individual observed policy choice is independent of the choices of others. Another potential source of interdependence across policy choices arises from membership of regional trade agreements. In this regard, the role the European Commission played in replacing and then reining back export controls imposed initially by Member States is worthy of further study.

Econometric analyses could be complemented by well‐chosen country case studies. For instance, the Indonesian government started by exhorting local producers not to sell face masks abroad. Subsequently, the government imposed an export limit or share. When that did not ‘work’ exports of masks were banned. This sequence of policy steps is different than jumping in with an export ban in the first place, reflecting, potentially, different political economy factors. Another example relates to Vietnamese export controls on rice. The government initially banned exports, but then the Prime Minister progressively watered down and abandoned export controls. News reports suggest opposition from rice farmers was important but did other factors play a part in this policy reversal?

An example of research in this vein concerns the relationship between recourse to export controls and actions to facilitate imports. Do governments that impose export restrictions also act on the import side? Insofar as governments are expected to use both types of policy measures, we can examine whether there is more liberalisation on the import side conditional upon imposing export restrictions by estimating an equation as follows:

| (1) |

where and are the logarithm of 1 plus the number of import liberalising and export restricting measures, respectively, implemented by jurisdiction ; is a vector of control variables; is a constant and the error term. The results from estimating equation ((1), (2)) using the Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood Estimator, reported in Table 5, suggest that conditional upon having imposed export restrictions on medical products, there is more liberalisation on the import side (the coefficient on export restrictions is statistically significant at 1%). Ceteris paribus and on average, a 10% rise in the number of export restrictions is found to be associated with a 5% increase in the number of import liberalisation measures. This is consistent with countries using trade policy instruments in response to the crisis by targeting both the import and export margin of trade.

TABLE 5.

Import liberalisation conditional on export controls (medical products)

| Dependent variable |

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

0.54*** | |

| (0.18) | ||

|

|

0.59** | |

| (0.21) | ||

| Constant | −1.69** | |

| (0.83) | ||

| Observations | 108 | |

| R‐squared | 0.59 |

Regression includes controls for government effectiveness; revealed comparative advantage; population; GDP weighted geographic distance to global markets; number of COVID‐19 cases and import dependence. Robust standard errors, clustered by country, in parentheses.

Levels of significance: 10%,

5%,

1%.

The role of foreign policy variables, for example, national security/defence considerations, potential retaliation, or the extent to which countries give preferential treatment to (some) developing countries or former colonies is another potential research question. A feature of the implementation of export restrictions in the EU was that actors could request exemptions based on such considerations. But presumably, there was also lobbying by countries, firms and interest groups (NGOs) for selective removal of trade measures. An assessment of the impact of trade policy changes in exporting countries on developing countries using the data set could be an input into such more granular political economy research questions.

4.2. Policy impact

A second set of potential questions revolves around the quantification of the effects of different trade policy strategies. Natural outcome variables varying at the country, sector and time level include trade flows, extent of/reliance on GVC participation and positioning, and (changes in) offshoring and reshoring. Observed trade policy strategies may also be associated with firm‐specific performance, the timing and scope of fiscal policies or features of applied lock‐down measures.

As an example, consider the potential impact that decreases in the global supply of food and medical products could have on international prices because of an increase in export restrictions.15 To calculate the impact of restrictions imposed on product k on its international price, we use a standard partial equilibrium approach and divide changes in global supply of such product by its import elasticity:

| (2) |

Changes in global supply are captured by the share of world exports covered by exports bans that were imposed by exporters between January and October 2020.16 Product elasticities are estimated for a panel covering 152 importing countries by Fontagné et al. (2019) and are assumed to be constant across countries. Our estimates focus on those restrictions that prohibit exports (export bans) and, therefore, could be considered as a lower bound estimation of the potential impact of restrictive export policy on prices.

Results by product category are presented in Table 6.17 Food prices rise by 0.7 percent on average, with increases in prices for different food categories ranging between 0.1 for chemical products such as pesticides to 1.2 for fresh fruits and vegetables. The impact of export bans on medical products is more pronounced: prices increase by 3.3 percent on average, with increases of 12.9 percent on prices of key critical items identified by the World Health Organisation Covid‐19 Disease Community Package (DCP). Within this, personal protective equipment such as face masks and protective clothing experienced increases in prices of 22.2 percent and 20 percent, respectively.

TABLE 6.

Export supply and price effects of export bans

| Product | Affected trade share (%) | Change in prices (Trade weighted) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Products | 8.1 | 3.3 |

| Critical Products | 7.4 | 12.9 |

| Case Management | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| Diagnostics | 7.1 | 1.4 |

| Hygiene | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Personal Protection Equipment | 40.0 | 17.7 |

| Non‐Critical Products | 8.3 | 1.4 |

| Anti‐epidemic goods | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Food preparations | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Manufacturing of Masks | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Medical Equipment | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Medical Supplies | 7.4 | 2.4 |

| Medicines | 14.4 | 1.1 |

| Food products | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Cereals | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Chemical products | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Fertilisers | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fresh Fruits – Vegetables | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Inputs for animal feed | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Miscellaneous edible preparations | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Oil‐bearing | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Seeds | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Stimulant crops | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sugar | 3.6 | 0.9 |

| Vegetable and animal oils | 1.0 | 0.6 |

4.3. Compatibility with WTO rules and trade agreement commitments

The trade policy monitoring exercise does not take a view on the consistency of changes in trade policy registered with a jurisdiction's commitments under the WTO or extant regional trade agreements. However, the extent and determinants of compliance with obligations is an important research question. Trade agreements permit governments to restrict trade in response to a public health emergency such as the COVID‐19 pandemic, but whether and how this is done may reflect a desire to exempt close partners and may or may not result in designing interventions to conform with rules relating to transparency and temporariness of measures. One reason why the data set reports whether measures are open‐ended or time‐bound is that such information is needed to assess performance considering international disciplines. The data set permits analysis of compliance with—and the effects of—applicable trade agreements. An example of such research is Hoekman et al. (2021), who investigate the relationship between the use of trade policy observed in the first 6 months of the pandemic and characteristics of national public procurement regimes, including membership of the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement and deep trade agreements that include provisions on public procurement. They find statistically strong associations between characteristics of public procurement regimes and the use of trade policy by countries.

A related research question concerns the potential impact of cooperation aimed at enhancing transparency. Several observers have pointed to the Agricultural Monitoring and Information System (AMIS) as a possible factor limiting recourse to export restrictions on food—and a potential model for cooperation to generate information on production capacity and trends in markets for critical medical supplies (Hoekman, Fiorini, et al. 2020). Does the way AMIS was designed and executed—maybe in terms of crops covered and information collected and made available—account for the smaller number of export controls observed for food? Here it would be important to understand where this transparency mechanism has teeth and where it shows up in the data.

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

This paper presents new high‐frequency data on trade policy changes in two sectors that are critical during the COVID‐19 pandemic: medical goods and medicines, and agricultural and food products. The data were collected on a weekly basis, and span the period from January 2 to mid‐October, 2020.18 The data record the jurisdiction implementing policy changes, the direction of the measure, type of measure, the timeline of the measure, and products covered by the policy.

The data reveal several stylised facts over the first nine months of the COVID‐19 pandemic:

There was a big jump in trade policy activism starting in February 2020. This accelerated in March, with the initial increase occurring in tandem with the rise in the number of COVID‐19 cases. At the global level, there is an approximate balance between temporary (time‐bound) and open‐ended measures, but significant heterogeneity at the regional/country level.

Measures targeting medical products and PPE dominate, accounting for two‐thirds of all trade measures taken. Food is less in focus. In terms of the value of 2019 trade covered, trade policy changes in medical goods outweigh those in food products by a factor of 3 or more.

Export curbs in medical goods covered international trade worth $135 billion (of 2019 trade), whereas import reforms in the same sector covered $165 billion. In the case of food and agri‐food products, the comparable totals are $39 billion and $42 billion, respectively. Because these estimates are based on 2019 (i.e. pre‐pandemic) trade data, they are likely to understate the magnitudes of implicated trade, especially for medical products.

Countries responded to the COVID‐19 pandemic with different combinations of export controls and import liberalisation measures. Some acted both to restrict exports and to liberalise imports, creating long‐term changes in their pre‐COVID trade policy structures; others acted only on one margin, either restricting trade or liberalising it. Although many countries resorted to trade policy instruments, it is noteworthy that numerous countries did not.

There is also substantial heterogeneity across countries in the types of trade instruments used and the extent and speed with which crisis‐motivated trade measures were removed.

The patterns of observed trade policy activism in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic raise many questions regarding the determinants and underlying political economy of trade policy. We hope the data collection exercise will stimulate research on the drivers of trade policy responses to the pandemic, the choice of instruments, quantification of the effects of different trade policy strategies, and broader questions pertaining to the design and value of trade agreements as instruments to sustain international cooperation in times of crisis. These are just some of the research questions we have touched upon above; no doubt there are many others, including questions that are not directly related to trade.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This paper describes an EUI‐Global Trade Alert‐World Bank joint project to collect and report information on trade policy measures for food and medical products put in place during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We are grateful to Caroline Freund, David Greenaway and an anonymous referee for helpful comments and suggestions, and to the Global Governance Programme of the EUI Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies and the World Bank Umbrella Facility for Trade for financial support. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent.

1.

TABLE A1.

Specific measures included in the two broad categories of export restrictions and import facilitation

| Export Control | Import Facilitation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Export ban | 123 | Import Internal taxation | 54 |

| Export licensing requirement | 73 | Import licensing requirement | 13 |

| Export quota | 13 | Import quota | 8 |

| Export tax | 5 | Import tariff | 161 |

| Export‐related non‐tariff measure, nes | 2 | Import tariff quota | 15 |

| Export‐related, Unknown measure | 21 | Import‐related non‐tariff measure, nes | 5 |

| Import‐related, Unknown measure | 46 | ||

| Total | 237 | Total | 302 |

GTA Intervention Classes as included in the classification adopted in this paper. 106 measures are excluded from the current analysis (81 and 25 targeting imports and exports, respectively).

FIGURE A1.

World and regional aggregate trade policy responses and COVID‐19 cases.

Notes: For each regional sub‐figure the upper part plots the number of active trade policy measures and the absolute number of COVID‐19 cases over time while the lower part plots the weekly variation of COVID‐19 cases.

FIGURE A2.

Trade policy response in the medical sector, selected large countries.

Notes: Measures reported by announcement date and expected duration. A black contour indicates that no removal date is reported; a red contouring indicates that the measure is expected to be lifted after 31 Dec 2020.

Evenett S, Fiorini M, Fritz J, et al. Trade policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Evidence from a new data set. World Econ.2022;45:342–364. 10.1111/twec.13119

This paper describes an EUI‐Global Trade Alert‐World Bank joint project to collect and report information on trade policy measures for food and medical products put in place during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its affiliated organisations or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent.

Footnotes

Information on trade policy changes are processed and collated by the Global Trade Alert team. The data are posted at https://www.globaltradealert.org/ as well as at https://globalgovernanceprogramme.eui.eu/covid‐19‐trade‐policy‐database‐food‐and‐medical‐products/ and https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐trade‐policy‐database‐food‐and‐medical‐products.

For products this is the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS); for sectors, use is made of the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC).

Lower frequency (monthly) data collected by the GTA in the last quarter of 2020 do not reveal major changes in the patterns observed during the first three quarters of 2020. In early 2021, some jurisdictions imposed export controls on vaccines. This development is not covered in the data used in this paper but is being registered in updates of the data set that can be used by analysts.

In the case of the European Union, some Member States also took individual actions to restrict or encourage trade in medical supplies. These countries included Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Poland and Romania. In the analysis that follows the scores attributed to individual members of a custom union are added to whatever measures are implemented by the union. That is, the EU and its Member States are identified as distinct implementing jurisdictions. This permits identification of both the EU as an entity and individual EU countries in the scatterplots that follow, with data for Member States comprising those measures implemented on top of the EU‐level ones (which are identified by the label EU).

Note that the data do not include changes in health and safety standards applicable to the products concerned, that is, sanitary and phytosanitary measures and technical barriers to trade (product standards).

The ITC considers overseas and autonomous territories separately from the home country. This is not done in the GTA or WTO monitoring exercises. See https://www.macmap.org/covid19

The 2013 Agreement on Trade Facilitation similarly has transparency requirements, requiring WTO members to publish promptly information on import, export or transit restrictions or prohibitions.

This is consistent with the 14 May 2020, G20 Trade Ministerial commitment to: ‘Reduce sanitary and technical barriers by encouraging greater use of relevant existing international standards and ensuring access of information on relevant standards is not a barrier to enabling production of PPE and medical supplies.’

As noted, the GTA COVID‐19 monitoring exercise does not encompass SPS and TBT measures.

For example, Australia has more notifications to the WTO (6) than policies captured by the GTA (1). The latter aims to facilitate imports of PPE. Australia's WTO notifications pertain to updates for this one measure.

WTO information on notification and measures reported by the Secretariat were accessed on 9 October 2020 from https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/notifications_e.htm#:~:text=COVID%2D19‐,WTO%20members'%20notifications%20on%20COVID%2D19,notifications%20related%20to%20COVID%2D19 and https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/trade_related_goods_measure_e.htm, respectively.

Trade data are for 2019 as 2020 trade data were not yet available. The intention is simply to give a sense of the coverage of the trade measures used. The figures in Table 2 estimate the total value of 2019 trade in essential goods that were affected at least once according to the GTA data. The percentages reported in Table 3 are based on all interventions in force at the end of the given month, using as denominator the total value of 2019 world trade in food or medical essential goods, respectively

Although weekly collection of trade policy data ceased at the end of Q3 2020, information on COVID‐19‐related trade policy measures continues to be collected at a lower frequency. At the time of finalising this article for publication data are available through January 2021 and will continue to be extended over time.

The trade flows used to compute export shares are based on UN Comtrade statistics for 2019 or most recent year available. These calculations do not account for the total duration of the export bans imposed by countries.

To aggregate the estimations in equation 1 by product category we use a weighted average across products where the weights are represented by the share of world exports of each product.

Weekly data are available through October 15, 2020. As mentioned, looking forward data will continue to be compiled monthly.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at: https://globalgovernanceprogramme.eui.eu/covid‐19‐trade‐policy‐database‐food‐and‐medical‐products/, https://www.globaltradealert.org/ and/or https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐trade‐policy‐database‐food‐and‐medical‐products.

REFERENCES

- Baldwin, R. , & Evenett S. (Eds.) (2020). COVID‐19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won't Work. VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press. https://voxeu.org/content/covid‐19‐and‐trade‐policy‐why‐turning‐inward‐won‐t‐work [Google Scholar]

- Bown, C. (2020a). “Trump's trade policy is hampering the US fight against COVID‐19”. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade‐and‐investment‐policy‐watch/trumps‐trade‐policy‐hampering‐us‐fight‐against‐covid‐19

- Bown, C. (2020b). “EU limits on medical gear exports put poor countries and Europeans at risk”, March 24. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade‐and‐investment‐policy‐watch/eu‐limits‐medical‐gear‐exports‐put‐poor‐countries‐and

- Bown, C. (2020c). “COVID‐19: Trump’s curbs on exports of medical gear put Americans and others at risk”, April 9. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade‐and‐investment‐policy‐watch/covid‐19‐trumps‐curbs‐exports‐medical‐gear‐put‐americans‐and

- Espitia, A. , Rocha, N. , & Ruta, M. (2020a). Trade and the COVID‐19 crisis in developing countries. At https://voxeu.org/article/trade‐and‐covid‐19‐crisis‐developing‐countries

- Espitia, A. , Rocha, N. , & Ruta, M. (2020b). COVID‐19 and Food Protectionism: The Impact of the Pandemic and Export Restrictions on World Food Markets (Policy Research Working Paper; No. 9253). Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from World Bank website: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33800 [Google Scholar]

- Evenett, S. (2020). Sicken thy neighbour: The initial trade policy response to COVID‐19. The World Economy, 43(4), 828–839. [Google Scholar]

- Fontagné, L. , Guimbard, H. , & Orefice, G. (2019). Product‐Level Trade Elasticities (CEPII working paper 2019‐17). Retrieved from CEPII website: http://www.cepii.fr/CEPII/en/publications/wp/abstract.asp?NoDoc=12403 [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman, B. (2020). COVID‐19 trade policy measures, G20 declarations and WTO Reform, COVID‐19 trade policy measures, G20 declarations and WTO reform. In Evenett S., & Baldwin R. (Eds.), Revitalising Multilateralism: Pragmatic ideas for the new WTO Director‐General (pp. 63–70). CEPR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman, B. M. , Fiorini, H. , & Yildirim, A. (2020). COVID‐19: Export controls and international cooperation. In Baldwin R., & Evenett S. (Eds.), COVID‐19 and trade policy: Why turning inward won’t work (pp. 77–88). CEPR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman, B. , Shingal, A. , Eknath, V. , & Ereshchenko, V. (2021). COVID‐19. public procurement regimes and trade policy. The World Economy. 10.1596/1813-9450-9511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo, A. , & Ruta, M. (2020). Don’t close borders against coronavirus. Financial Times, 13 March. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2020). COVID‐19 and International Trade: Issues and Action. https://read.oecd‐ilibrary.org/view/?ref=128_128542‐3ijg8kfswh&title=COVID‐19‐and‐international‐trade‐issues‐and‐actions

- WTO . (2020). Trade in Medical Goods in the Context of Tackling COVID‐19. April. https://www.WTO.org/english/news_e/news20_e/rese_03apr20_e.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at: https://globalgovernanceprogramme.eui.eu/covid‐19‐trade‐policy‐database‐food‐and‐medical‐products/, https://www.globaltradealert.org/ and/or https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐trade‐policy‐database‐food‐and‐medical‐products.