Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to study anxiety and burnout among Division of Radiological Sciences (RADSC) staff during the COVID‐19 pandemic and identify potential risk and protective factors. These outcomes were compared with non‐RADSC staff.

Methods

A cross‐sectional online study was conducted between 12 March and 20 July 2020 in the largest public tertiary hospital receiving COVID‐19 cases. Burnout and anxiety were assessed with the Physician Work‐Life Scale and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder‐7 Scale, respectively. Workplace factors were examined as potential risk and protective factors using multivariable ordinary least squares regression analyses, adjusting for pertinent demographic characteristics.

Results

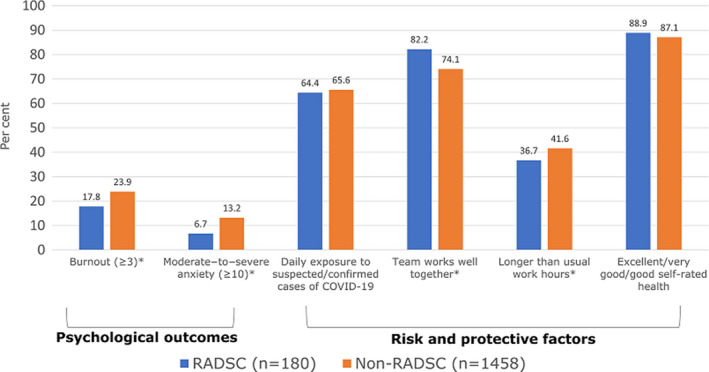

RADSC staff (n = 180) and non‐RADSC staff (n = 1458) demonstrated moderate‐to‐severe anxiety rates of 6.7 and 13.2 % and burnout rates of 17.8 and 23.9 %, respectively. RADSC staff reported significantly lower anxiety (mean ± SD: 4.0 ± 3.7 vs 4.9 ± 4.5; P‐value < 0.05), burnout (mean ± SD: 1.9 ± 0.7 vs 2.1 ± 0.8; P‐value < 0.01), increased teamwork (82.2% vs 74.1%; P‐value < 0.05) and fewer night shifts (36.7% vs 41.1%; P‐value < 0.01). Among RADSC staff, higher job dedication was associated with lower anxiety (b (95% CI) = −0.28 (−0.45, −0.11)) and burnout (b (95% CI) = −0.07 (−0.11,‐0.04)), while longer than usual working hours was associated with increased anxiety (b (95% CI) = 1.42 (0.36, 2.45)) and burnout (b (95% CI) = 0.28 (0.09, 0.48)).

Conclusions

A proportion of RADSC staff reported significant burnout and anxiety, although less compared to the larger hospital cohort. Measures to prevent longer than usual work hours and increase feelings of enthusiasm and pride in one’s job may further reduce the prevalence of anxiety problems and burnout in radiology departments.

Keywords: anxiety, burnout, COVID‐19, nuclear medicine, radiology

Introduction

The recent coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak has had an impact on many aspects of daily life. While the harmful physical aspects of COVID‐19 have been thoroughly examined, its psychological impact upon both the general population 1 and healthcare providers 2 may be equally damaging. There have been some early studies demonstrating the psychological impact upon general healthcare providers in terms of anxiety 3 and burnout 4 . However, there have been few studies examining the pandemic’s effect specifically upon radiology divisions 5 , and no studies showing how these effects compare to hospital cohorts as a whole. Our study aims to add to the literature on this topic.

In our institution, the departments of diagnostic radiology, interventional radiology, nuclear medicine and molecular imaging come under the umbrella of the Division of Radiological Sciences (RADSC), with a staff strength of over 700. Other departments in the hospital come under their respective divisions, such as the Division of Surgery and the Division of Medicine.

Anxiety is an emotional response in anticipation of a future concern and is associated with activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the fight‐or‐flight response. It may be a normal reaction to stress, such as from a deadly pandemic. In some instances, this reaction may prove beneficial, helping us to avoid dangers and stay vigilant, allowing behavioural modification and self‐preservation. However, if the stressor is prolonged and has no clear endpoint, it may lead to anxiety disorders which involve excessive anxiety, and ultimately hinder the ability to function normally. 6

Burnout is a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress characterized by three dimensions, namely feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, increased mental distance or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to work, and reduced professional efficacy. Potential contributing factors to burnout are myriad and include long working hours, lack of organizational control, rapid changes and inadequate training, among others. 7 In recent years, it has become recognized as a workplace‐related morbidity and should not be used to describe experiences in other facets of one’s life. 8 Dubbing burnout as an occupational phenomenon places as much responsibility upon the organization as on the individual; both sides need to work in concert for meaningful remediation. 9 Addressing burnout is important because not only is it associated with increased healthcare worker morbidity and job turnover, but has been linked with worse patient safety outcomes. 9

We aimed to take a snapshot of the prevalence of anxiety and burnout in our hospital during the COVID‐19 pandemic, to increase awareness of the problem and to look for potentially protective or risk factors in RADSC staff associated with anxiety and burnout, respectively. We controlled for demographic factors including age, sex, having children, living with vulnerable populations and self‐rated health status. We hypothesized that workplace factors such as exposure to COVID‐19, length of working hours, frequency of night shifts, higher job dedication and teamwork may be associated with burnout and anxiety.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross‐sectional online study utilizing a subset of data in Singapore General Hospital, from a larger project that prospectively follows healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Singapore Health Services, Singapore’s largest public healthcare cluster. The baseline data were collected between 12 March and 20 July 2020.

Participants

The focus of the paper was on healthcare workers from the RADSC division working in Singapore’s largest public tertiary healthcare hospital that was receiving COVID‐19 cases. The participants from RADSC division consisted of diagnostic radiologists, interventional radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, nurses, allied health professionals (mainly radiographers and nuclear medicine technologists) and other administrative support staff. Other divisions’ participants included doctors of various specialties, trainee doctors, nurses, allied health professionals (mainly physiotherapists and occupational therapists) and other administrative support staff.

Data collection

The online survey was made available on the Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) platform, which was accessed either via a web link or QR code. A reminder email was sent out at about three‐week intervals to increase the response rate. Participants provided informed consent online before completing the survey in English, which took approximately 15 min to complete.

Ethical consideration

The study was exempted from review by the SingHealth Centralized IRB (2020/2160) and approved by the National University of Singapore IRB (S‐20‐081).

Study outcomes

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder‐7 Scale. 10 The scale includes a total of 7 items examining anxiety symptoms over the last 2 weeks measured on a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. A higher score was indicative of higher anxiety.

Burnout

Job burnout was measured using a validated, non‐proprietary one‐item burnout question from the Physician Work‐Life Scale. The question conceptually captured the emotional exhaustion aspect of burnout and has been validated on different groups of healthcare workers, including registered nurses. 11 Respondents were asked to rate their level of burnout on a five‐category ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 5. A higher score was indicative of higher job burnout.

Factors associated with study outcomes

Exposure to suspected/confirmed cases of COVID‐19 was coded as high risk (occasional/daily contact) or low risk (no contact).

Job dedication was measured using 3 items from the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale‐9. 12 (UWES) job dedication subscale, with scores ranging from 0 to 18 with a higher score indicating higher job dedication.

Longer than usual working hours and night shifts in the past month were measured with binary options (yes/no).

Self‐rated health was measured using one item of the RAND 36‐item short‐form survey coded as 1 indicating excellent/very good/good self‐rated health or 0 indicating fair/poor health. 13

Living with persons with lower immunity specifically mentioned young children, elderly or persons with lowered immunity due to any cause.

Statistical analysis

We assessed differences in descriptive characteristics (demographic features), psychological outcomes (burnout and anxiety) and predictors of psychological outcomes for RADSC vs non‐RADSC staff using t‐tests/Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests for continuous variables and chi‐square/Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. We performed ordinary least square multivariable regression to investigate the association between psychological outcomes (burnout and anxiety) and risk (exposure to COVID‐19, night‐shift work, longer than usual working hours) and protective factors (job dedication and teamwork) after controlling for demographic features (age, gender and living with persons with lowered immunity) for RADSC staff.

Results

A total of 180 respondents from the RADSC division participated out of a total of 1,638 HCWs from SGH. The RADSC respondents, compared to non‐RADSC respondents, were older and had a higher proportion of males (P‐value = 0.000) (Table 1). There were slightly more doctors who responded from RADSC (22% compared to 14% in the rest of the institution). More allied health professionals from RADSC such as radiographers responded to the survey, whereas more nurses from the larger cohort responded.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of RADSC vs non‐RADSC staff at baseline

| RADSC, n = 180 | Non‐RADSC, n = 1458 | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 38.6 (12.4) | 35.7 (10.6) | 0.000 ‡,** |

| Female, n (%) | 113 (62.8) | 1,136 (77.9) | 0.000 †,** |

| Married, n (%) | 82 (45.6) | 761 (52.2) | 0.093† |

| Living with vulnerable population with lowered immunity, n (%) | 81 (45.0) | 709 (48.6) | 0.358† |

| Occupation, n (%) | |||

| Doctor | 39 (21.7) | 394 (14.0) | 0.000 † , ** |

| Nurse | 4 (2.2) | 909 (62.3) | |

| Allied health professionals (radiographers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, etc) | 106 (58.9) | 185 (12.7) | |

| Others (e.g. clerical, laboratory staff) | 31 (17.2) | 160 (11.0) | |

| Psychological outcomes | |||

| Burnout score, mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.8) | 0.002 ‡,**, ‡ |

| Burnout score ≥ 3, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 32 (17.8) | 348 (23.9) | 0.068† |

| No | 148 (82.2) | 1110 (76.1) | |

| Anxiety – GAD score, mean (SD) | 4.0 (3.7) | 4.9 (4.5) | 0.035 § , * |

| Moderate‐to‐severe anxiety (GAD ≥ 10), n (%) | |||

| Yes | 12 (6.7) | 192 (13.2) | 0.013 †,* |

| No | 168 (93.3) | 1266 (86.8) | |

| Risk and protective factors | |||

| Exposure to suspected/confirmed cases of COVID‐19 | |||

| Daily/Occasionally | 116 (64.4) | 957 (65.6) | 0.751† |

| Never | 64 (35.6) | 501 (34.4) | |

| Job dedication, mean (SD) | 13.0 (3.1) | 12.5 (3.4) | 0.071‡ |

| Team works well together – yes, n (%) | 148 (82.2) | 1081 (74.1) | 0.018 † , * |

| Night shifts in the past month – yes n (%) | 50 (27.8) | 726 (49.8) | 0.000 † , ** |

| Longer than usual work hours in the past month – yes, n (%) | 66 (36.7) | 607 (41.6) | 0.201† |

| Self‐rated health, n (%) | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 160 (88.9) | 1270 (87.1) | 0.498† |

| Fair/Poor | 20 (11.1) | 188 (12.9) | |

Bold values indicate statistically significant results at a P‐value of less than 0.05.

and * denote significance at 1% and 5% level, respectively.

Chi‐square test.

t‐test.

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U‐test.

RADSC respondents, compared to the larger hospital cohort, reported significantly lower mean scores of anxiety (4.0 vs 4.9, P = 0.035) as well as burnout (1.9 vs 2.1, P = 0.002). While the exposure to COVID‐19 was similar between the cohorts, there was a significantly higher proportion who reported better teamwork (82.2% vs 74.1%, P = 0.018) and a lower proportion reporting night‐shift work (27.8% vs 49.8%, P = 0.000) in RADSC compared to the rest. Other work‐related factors were not statistically significantly different between the two study cohorts in this study (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A graphical representation of the psychological outcomes measured by our study and potential risk and protective factors. *Denotes statistically significant differences, with the P‐value < 0.05.

When we looked more closely at potentially protective or risk factors among RADSC staff only (N = 180) (Table 2), both anxiety and burnout were associated with longer than usual working hours (b (95% CI) = 0.28, 95% confidence interval (0.09, 0.48), 1.42 (0.36, 2.45), respectively) and younger age of respondents (−0.01 (−0.02, 0), −0.06 (−0.10, −0.01), respectively). A high job dedication score was associated with significantly lower rates of reported anxiety and burnout (−0.07 (−0.11, −0.04), −0.28 (−0.45, −0.11), respectively). Female respondents reported higher anxiety scores (1.39 (0.37, 2.42)). As a sensitivity analysis, we checked whether age moderated the association between job dedication/ longer working hours and our psychological outcomes of interest. The interaction was insignificant for both the outcomes.

Table 2.

Predictors associated with psychological outcomes of RADSC staff, n = 180

| Burnout | Anxiety | |

|---|---|---|

| Coeff [95% CI] | Coeff [95% CI] | |

| Variables of interest | ||

| Exposure to suspected/confirmed cases of COVID‐19 (reference: never) | ||

| Daily/occasionally | 0.05 [−0.16, 0.26] | 0.85 [−0.26, 1.97] |

| Job dedication | −0.07 [−0.11, −0.04]** | −0.28 [−0.45, −0.11]** |

| Team works well together (reference: no/neutral) | ||

| Yes | −0.14 [−0.38, 0.10] | −1.17 [−2.45, 0.13] |

| Night shifts in the past month (reference: no) | ||

| Yes | 0.10 [−0.14, 0.33] | −0.45 [−1.72, 0.82] |

| Worked longer than usual hours in the past month (reference: no) | ||

| Yes | 0.28 [0.09, 0.48]** | 1.42 [0.36, 2.45]** |

| Control variables | ||

| Female (reference: male) | 0.07 [−0.12, 0.26] | 1.39 [0.37, 2.42]** |

| Age | −0.01 [−0.02, −0.00]* | −0.06 [−0.10, −0.01]* |

| Living with children, elderly or vulnerable persons with lowered immunity (reference: no) | −0.06 [−0.25, 0.12] | −0.20 [−1.19, 0.80] |

| Self‐rated health (reference: fair/poor) | ||

| Excellent/very good/good | −0.25 [−0.55, 0.04] | −0.63 [−2.22, 0.96] |

Bold values indicate statistically significant results at a P‐value of less than 0.05.

and * denote significance at 1% and 5% level, respectively.

Discussion

COVID‐19 has created challenges to healthcare systems and its workers across the globe. It has forced hospitals to reorganize their operational workflows, 14 compelled educators to put learning materials online 15 and even altered the way research is practised. 16 Because the pathogen may spread by way of large droplets when people are in close proximity, the ensuing safe distancing measures have forced us physically apart. 17 It is reasonable to hypothesize the numerous changes have had a cumulative effect and have taken a toll on the mental health of healthcare workers.

We chose to focus on anxiety and burnout as measures of staff psychological well‐being because although they are linked, they are distinct and have the potential to impact the long‐term functioning and efficiency of an institution. Although both are indices of psychological well‐being during stressful periods as during the COVID‐19 pandemic, anxiety can be thought to be more sensitive to the impact on the person due to more general factors such as demographics, family environment and workplace. 18 Burnout would be useful to understand the impact of workplace factors on psychological morbidity to staff. 19

A survey of 689 United States (US) radiologists during the early stages of the COVID‐19 pandemic (April 2020) reported that 61% of respondents rated their anxiety levels to be high, and the most commonly cited stressors were family health (71%), personal health (47%) and financial concerns (33%). 20 Another study cited eight sources of anxiety for staff, including access to childcare, long work hours and demands, new areas of deployment, lack of access to up‐to‐date information, access to personal protective equipment, exposure to COVID‐19, lack of access to rapid testing and uncertainty of organizational support. 21 A pre‐COVID 2014 survey of US radiologists showed that 61% of radiologists reported burnout. 22

Locally within Singapore, there have been no pre‐pandemic studies on radiology divisions or radiologists specifically with regard to burnout, although there have been studies focused on intensive care physicians, 23 anaesthesia 24 and medical 25 residents as well as nurses. 26 These studies show the prevalence of burnout range from 40 to 80%; the authors of these studies utilized the Maslach burnout score and Oldenburg burnout inventory, while we used the Physician Work–Life Scale. 27 Given the inherent differences in cohorts and psychological tests used to measure psychological morbidity, it is difficult to draw meaningful conclusions between our results and the published pre‐pandemic data.

We found that our RADSC sample reported lower burnout and anxiety compared to previous published studies 28 (although direct comparison may not be possible) and to our larger local hospital cohort, despite similar proportions of exposure to suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 cases (a proportion of RADSC staff included within the study had been redeployed to the emergency department and makeshift facilities directly catering to known COVID patient populations; further, RADSC includes radiographers and doctors that normally have frequent patient contact, such as interventional radiologists and nuclear medicine physicians). We also found that job dedication and teamwork were stronger among RADSC staff compared to the larger hospital cohort, with the latter noted to be statistically significant. Among the RADSC staff, length of working hours and job dedication were factors that could potentially reduce burnout and anxiety in radiology departments. These factors are relevant pre‐pandemic but are particularly so in the midst of a pandemic where healthcare staff are further stretched. If these factors can be properly addressed, the psychological morbidity associated with COVID‐19 could be mitigated.

We have tried to control, using multivariate analyses, for some of these known factors as part of the study, while some other factors were controlled more on a national level. For example, we fortunately have sufficient reserves of personal protective equipment, rapid testing and ready access to up‐to‐date information. 29 These would therefore be less relevant sources of anxiety in our healthcare staff but are still pertinent areas to address in order to reduce the impact of COVID‐19.

While analysing what methods RADSC has utilized to increase job dedication and ultimately foster resilience, we have identified 3 possible sources. The first and perhaps most important is promoting a clear direction and sense of purpose. The RADSC vision and mission (illuminating lives through excellence in medical imaging and leading medical imaging through patient‐centric care, innovation, and academic excellence) is ubiquitous both in electronic and paper form, both on our intranet website and within reading rooms, image acquisition areas, and administrative offices. Next, our RADSC leadership prioritizes clear and open channels of communication. At the onset of the pandemic, chat groups were quickly formed across our RADSC division to disseminate up‐to‐date information and instructions seamlessly during the initial period of uncertainty. Finally, words of encouragement and appreciation continued to be expressed by both radiology leadership and the public; thank you cards are pasted on our dining area walls and our RADSC division regularly distributes care packs containing notes of appreciation from the public and hygiene products such as hand sanitizer and facemasks. 30

A potential weakness of the study as with all survey‐based studies is that it is voluntary with no control over the study participants’ demographics and response rates. Another potential confounder we addressed was the possible association between older age of the respondents and increased job dedication and reduced working hours, but there was no statistically significant association in our study population. Finally, we have no specific radiology or radiology department baseline local data prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic, and it is difficult to prove our results are solely due to COVID‐19. However, we can compare between divisions and surmise that certain factors may be able to account for the lower reported rates of anxiety and burnout in RADSC. Given the rapidly evolving landscape surrounding the virus, the results could be different if the survey were conducted in another phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

One of the strengths of our survey is the sizeable number of respondents from different healthcare professions and subspecialties, allowing us a more in‐depth perspective on how hospital organizations could modify certain factors to protect against psychological morbidity experienced during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

In conclusion, work hours and job dedication are potentially modifiable factors that are associated with lower reported levels of anxiety and burnout in radiology departments, particularly during stressful periods as encountered during the COVID‐19 pandemic. If these factors can be properly addressed, the psychological morbidity associated with COVID‐19 could be mitigated.

Acknowledgements

We wish to dedicate this work to all frontline healthcare staff and to all who have suffered in any shape or form due to COVID‐19.

HL Huang MBChB MRCP; RC Chen MD; I Teo PhD; I Chaudhry MSc; AL Heng MSc; KD Zhuang MBBS FRCR; HK Tan MBBS FRCS PhD; BS Tan MBBS FRCR.

Conflict of interest: All authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interests from publication of this article.

References

- 1. Zhao H, He X, Fan G et al. COVID‐19 infection outbreak increases anxiety level of general public in China: involved mechanisms and influencing factors. J Affect Disord 2020; 276: 446–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID‐19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 88: 559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS et al. Is returning to work during the COVID‐19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 87: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fessell D, Cherniss C. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and beyond: micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am College Radiol 2020; 17: 746–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Konstantopoulou G, Iliou T, Karaivazoglou K, Iconomou G, Assimakopoulos K, Alexopoulos P. Associations between (sub) clinical stress‐ and anxiety symptoms in mentally healthy individuals and in major depression: a cross‐sectional clinical study. BMC Psychiat 2020; 20: 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harolds JA, Parikh JR, Bluth EI, Dutton SC, Recht MP. Burnout of radiologists: frequency, risk factors, and remedies: a report of the ACR Commission on Human Resources. J Am Coll Radiol 2016; 13: 411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greco G. Effects of combined exercise training on work‐related burnout symptoms and psychological stress in the helping professionals. J Hum Sport Exerc 2020; 10.14198/jhse.2021.162.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Health workforce burn‐out. Bull World Health Organ 2019; 97: 585–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e015141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD‐7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 582–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross‐national study. Educ Psychol Meas 2006; 66: 701–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self‐rated health question. J Gen Int Med 2006; 21: 267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chia AQX, Cheng LTE, Sim WY, Hong WL, Chen RC. Chest radiographs and CTs in the era of COVID‐19: indications, operational safety considerations and alternative imaging practices. Acad Radiol 2020; 27: 1193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robbins JB, England E, Patel MD, Debenedectis CM, Sarkany DS, Heitkamp DE et al. COVID‐19 impact on well‐being and education in radiology residencies: a survey of the association of program directors in radiology. Acad Radiol 2020; 27: 1162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vagal A, Reeder SB, Sodickson DK, Goh V, Bhujwalla ZM, Krupinski EA. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the radiology research enterprise: radiology scientific expert panel. Radiology 2020; 296: E134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang HL, Allie R, Gnanasegaran G, Bomanji J. COVID19‐nuclear medicine departments, be prepared!. Nucl Med Commun 2020; 2020: 297–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ivandic I, Kamenov K, Rojas D, Cerón G, Nowak D, Sabariego C. Determinants of work performance in workers with depression and anxiety: a cross‐sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14: 466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robert R, Kentish‐Barnes N, Boyer A, Laurent A, Azoulay E, Reignier J. Ethical dilemmas due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Ann Int Care 2020; 10: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Demirjian NL, Fields BKK, Song C et al. Impacts of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic on healthcare workers: a nationwide survey of United States radiologists. Clin Imaging 2020; 68: 218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA 2020; 323: 2133–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chetlen AL, Chan TL, Ballard DH et al. Addressing burnout in radiologists. Acad Radiol 2019; 26: 526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. See KC, Zhao MY, Nakataki E et al. Professional burnout among physicians and nurses in Asian intensive care units: a multinational survey. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44: 2079–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lim WY, Ong J, Ong S et al. The abbreviated Maslach burnout inventory can overestimate burnout: a study of anesthesiology residents. J Clin Med 2019; 9: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kooraki S, Hosseiny M, Myers L, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus (COVID‐19) outbreak: What the department of radiology should know. J Am Coll Radiol 2020; 17: 447–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ang SY, Dhaliwal SS, Ayre TC et al. Demographics and personality factors associated with burnout among nurses in a Singapore tertiary hospital. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LLL et al. Psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Int Med 2020; 173: 317–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rajhans P, Deb KS, Chadda RK. COVID‐19 Pandemic and the mental health of health care workers: awareness to action. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci 2020; 56: 171–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheng LTE, Chan LP, Tan BH et al. Déjà vu or jamais vu? How the severe acute respiratory syndrome experience influenced a Singapore radiology department’s response to the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic. Am J Roentgenol 2020; 214: 1206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen RC, Cheng LTE, Lim JLL et al. Touch me not: safe distancing in radiology during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Am Coll Radiol 2020; 17: 739–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]