Abstract

This study explores consumer behavior during the pandemic through the lens of social cognitive theory (SCT). Using the SCT framework and assessing the pandemic as an environmental set, this study strives to fill the gaps in the underexplored impacts of the personal processes of consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability on the behavioral processes of purchase satisfaction and repurchase. The research results show that consumers are self‐efficacious to a degree when it comes to purchase decision making in the context of pandemics. Vulnerability and resilience directly influence the purchase satisfaction and indirectly influence the repurchase intention via satisfaction. Furthermore, purchase satisfaction positively affects the repurchase intention. In addition, research results show that consumer adaptability to online shopping moderates the relationship between consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction. These findings have practical implications in terms of marketers’ communication strategy development.

Keywords: adaptability, consumer resilience, consumer vulnerability, purchase satisfaction, repurchase, self‐efficacy, social cognitive theory

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has fundamentally changed the world. The pandemic forced consumers to change their attitudes and purchasing habits (Wright & Blackburn, 2020). Health and economic issues, such as resource scarcity and panic buying (Prentice et al., 2021), greater safety/protection concerns and contactless payments, forced consumers to reconsider their future purchase decisions (Mehrolia et al., 2020), and retailers to reshape their businesses in real time (Standish & Bossi, 2020). The current pandemic can be perceived as an adverse setting that can make some people vulnerable and/or resilient, affecting their purchase decision making. According to Brennan et al. (2017), vulnerability is more about the situation that people encounter than about the people themselves. This suggests that an individual might feel vulnerable at any point in time, including while making purchases during the pandemic. When faced with stressful situations, individuals might exhibit negative coping styles and a low sense of self‐efficacy, resulting in higher vulnerability (Muris et al., 2001). The stronger the coping self‐efficacy is, the less vulnerable the individuals are (Ozer & Bandura, 1990). The same notion can be applied to resilience; it is expected that more self‐efficacious individuals are those who are more resilient.

“Consumer vulnerability is a state of powerlessness that arises from an imbalance in marketplace interactions or from the consumption of marketing messages and products. It occurs when control is not in an individual’s hands, creating a dependence on external factors (e.g., marketers) to create fairness in the marketplace” (Baker et al., 2005, p. 134). Consumer vulnerability evokes a feeling of helplessness, that is, a loss of control over consumption experience, creating a higher dependence on external sources, such as marketers (Ford et al., 2019).

Recent studies have begun to focus more on the market perspective by investigating consumer vulnerability from the perspectives of poverty and low‐income (Bryant & Hill, 2019; Choudhury et al., 2019; Glavas et al., 2020), decision making (Choudhury et al., 2019; Hill & Sharma, 2020), and the marketplace (Ford et al., 2019; Glavas et al., 2020; LaBarge & Pyle, 2020; Stewart & Yap, 2020). However, less is known about consumer vulnerability and behavioral purchasing outcomes, such as purchase satisfaction and repurchase, given the adverse (pandemic) situation. Hence, our study aims to shed light on this aspect.

In addition to the vulnerability aspect, difficult situations can tell a lot about one’s resilience, which refers to the individual’s confrontation with disruptive processes and perception of handling them in terms of the socioeconomic context (Maurer, 2016). While some scholars claim that vulnerable people lack resilience, others argue differently. According to Miller et al. (2010), vulnerability and resilience represent related but different concepts in understanding the changes. In addition, it seems that people can be simultaneously vulnerable and resilient (Uekusa & Matthewman, 2019). According to Lorenz and Dittmer (2016), people in disasters are rarely helpless, but are rather proactive and self‐determined in finding ways of coping with the disaster, which calls for examining the role of their self‐efficacy through resilience. Moreover, researchers note that social scientists have only recently started to conceptualize resilience and conduct empirical research on this interesting field (Maurer, 2016; Mayntz, 2016), suggesting the existence of a large gap between scientific and practical implications of how to apply the concepts of both vulnerability and resilience (Miller et al., 2010). Hence, our study aims to address this gap as well.

Drawing on the definition of consumer vulnerability proposed by Baker et al. (2005), wherein it arises from the interaction of personal states, characteristics, and external conditions within a context, it seems worthwhile to explore the consumer vulnerability and resilience within the COVID‐19 setting through the lens of SCT. In other words, the current situation offers a possibility for exploring consumers’ vulnerability, resilience, and consequent behavioral purchasing outcomes, especially since the COVID‐19 pandemic brought uncertainties in terms of consumers’ behavior patterns and responses to companies’ efforts to satisfy their needs. Therefore, the pandemic setting might be considered an environmental stimulus that influences the individuals’ personal and behavioral processes, showing how efficacious individuals might be when coping with a change and the effect of their coping in the retail context. Since a similar framework has not been utilized so far, we strive to fill this gap using SCT and the self‐efficacy determinant (Bandura, 1991, 1998, 2001, 2005; Maddux, 1995). Hence, this study makes several contributions to the literature. First, it adds to the SCT environmental set by exploring the retail context in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Second, the exploration of the SCT personal processes set and the self‐efficacy (SE) subset is enhanced by investigating the consumer attitudes and perceptions through consumer vulnerability and resilience. Third, the self‐efficacy (SE) subset is also investigated through the moderating variable of consumer adaptability, which is understood as consumers’ perceptions of the pandemic as an opportunity for learning. Fourth, another SCT contribution is the assessment of behavioral processes in the form of purchase satisfaction and repurchase. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate consumer vulnerability and resilience and their impact on purchase satisfaction and repurchase, given the COVID‐19 pandemic setting, through the lens of SCT. Finally, this study offers practical implications for marketers in terms of a better understanding of consumers’ personal and behavioral processes and enhancement of the purchasing experience in the COVID‐19 and post‐COVID‐19 periods.

2. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

This study was conducted in Croatia, where the first positive COVID‐19 patient was recorded in February 2020, when the government introduced various measures to fight COVID‐19 (Government of the Republic of Croatia, 2020). Subsequently, from March to mid‐May 2020, Croatia faced a lockdown and a reopening afterward to prepare for the tourism season (OECD, 2020). During the pandemic, the lockdown in particular, retailers and consumers largely moved online (Dujić, 2020). This period was particularly stressful and new for Croatian consumers, given the prevalence of online shopping. Even before the pandemic, Croatia, like most emerging countries, lagged behind the European average in online purchases (Eurostat, 2020); in 2019, only 40% of the Croatian population shopped online, while in the European Union, this percentage was up to 80% (Dujić, 2020). Therefore, the pandemic caught Croatian consumers slightly unprepared, which only deepened the fear of the unknown, making them vulnerable, yet forcing them to exhibit their self‐efficacy (i.e., resilience) by finding ways to cope with the threat, including the possibility of buying goods online.

The Croatian market records significant changes in consumer behavior. The demand for products that can be easily consumed at home, well‐known brands, and products that positively affect well‐being has increased significantly (Vrdoljak, 2020). Consumers prefer the constant availability of such products, which means that companies have to adapt their offers as well. Adaptations can also be noticed in the rise of e‐commerce, which has consequently stimulated Croatian companies to invest more in advertising, with special emphasis on digital communication and social media (Vrdoljak, 2020). Croatian consumers are shopping less frequently, but in larger quantities (Hendal, 2020), and are now buying more rationally (JaTrgovac, 2020), while shifting toward a healthier lifestyle (Progressive, 2020). Moreover, it seems that Croatian consumers have now increased their online purchasing (up to 52%), and more than 6% had not previously purchased products online (Equestris, 2020). Most products purchased online are clothes, shoes, home accessories, and multimedia products (Hina, 2020).

Considering previous notions, it can be seen that consumer behavior undergoes certain changes because of external influences, such as the COVID‐19 pandemic. However, it is important to assess how consumers’ personal processes of coping with vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability to change through online purchasing add to their behavioral processes in terms of retail/purchase satisfaction and repurchase. This is crucial for companies’ future strategies and communication approaches. Hence, we aim to explain these processes by utilizing SCT. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no attempt to include these concepts in the SCT framework. In this regard, we expect that, given the COVID‐19 pandemic (SCT environmental aspect), consumers will strive to become more self‐efficacious (SCT personal processes through vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability) in obtaining retail satisfaction and repurchase (SCT behavioral processes). First, they might strive to reduce their vulnerability by relying on product promotions, product knowledge, and abilities to purchase and distinguish to achieve the ability to make purchase decisions (e.g., purchase, purchase satisfaction, and repurchase). Second, we expect that consumers will strive to build their resilience by making appropriate purchase decisions, achieving purchasing satisfaction, and possibly repurchasing. By doing so, consumers might also demonstrate self‐efficaciousness by adopting the possibility of buying products online, in other words, by perceiving the pandemic as an opportunity to learn new ways of acquiring goods. Third, we believe that satisfactory purchase experience, impacted by self‐efficacy in a form of reduced vulnerability and increased resilience, will add to further decision‐making processes (repurchase decisions). In this way, we strive to contribute to enriching the SCT framework by (a) exploring a novel environmental aspect (the pandemic), (b) adding new constructs of consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability to the self‐efficacy personal processes dimension, and (c) enhancing the behavioral processes set contributing to SCT knowledge with purchase satisfaction and repurchase constructs.

3. THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

3.1. Social cognitive theory (SCT) and purchase decision making

Social cognitive theory (SCT) explains human behavior through environmental, personal, and behavioral influences or theory sets (Bandura, 1991, 1998, 2001). Self‐efficacy, as an SCT (sub)set, represents a self‐regulatory mechanism that denotes not only the skill or capability of performing, but also the self‐belief in the capability of being efficacious, that is, being able to enhance motivation and problem‐solving efforts (Bandura, 1998). According to Young et al. (2005), outcome expectancy and self‐efficacy beliefs are constructs central to SCT. Regarding outcome expectancy, people are motivated to perform a particular behavior if they feel driven, while self‐efficacy deals with judgments of one’s learning and performing actions when handling the prospective situation (Schunk & Pajares, 2009; Young et al., 2005). Similarly, for the purpose of our study, it is central to reason whether consumers might be motivated to achieve the behavioral outcomes of purchase satisfaction and repurchase if they feel more self‐efficacious, that is, less vulnerable (e.g., with the available product promotions, product knowledge, and purchase ability) and more resilient. In other words, would they be more motivated to overcome the pandemic threat with respect to the buying possibilities? In addition, we see self‐efficacy as a personal process that can be investigated through the consumers’ ability to adapt to the new situation, for instance, by learning about the new means of buying products (online).

Behavioral outcomes (trial, purchases, and repurchase) are an important part of the consumer decision‐making process (Schiffman et al., 2012), and satisfaction represents a crucial consumer variable reflecting how much the purchased goods satisfy or exceed customers’ expectations (Farris et al., 2010). It is important to study the construct of purchase satisfaction, especially when new and potentially harmful circumstances, such as pandemics, that severely affect consumer behavior occur. Namely, during crises, people tend to be more cautious and focus on functional aspects, hence reducing or postponing purchases (Skordoulis et al., 2018). Other researchers (Skowron & Kristensen, 2011) indicate that, when faced with a crisis, consumers from developing European countries tend to be less satisfied with their purchases and tend to be less loyal to firms they trust when compared with consumers from developed EU economies. In addition, personal characteristics should not be neglected in terms of their potential significance for customer satisfaction (Cameran et al., 2010). Therefore, it is expected that this study will provide novel insights into consumer purchase satisfaction and repurchase during the COVID‐19 pandemic, given consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability.

This study will assess self‐efficacy through the aspects of vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability. On the one hand, vulnerability describes one’s reduced capacity to attain one’s own benefits, and it is determined by psychosocial characteristics and contextual and environmental conditions (Hill & Sharma, 2020; LaBarge & Pyle, 2020). On the other hand, resilience refers to one’s capability to cope well with stress or change and the ability to recover quickly from such adversity (Baker et al., 2005). Hence, all constructs tell a lot about one’s self‐efficacy. As this study is placed within the COVID‐19 retail setting, self‐efficacy (through vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability to online means) represents a coping mechanism (being motivated) for obtaining purchase satisfaction and repurchase (problem‐solving efforts). In the sense of SCT and SE, vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability (i.e., perception of the pandemic as an opportunity for learning) represent aspects of self‐efficacy that add to the personal processes set of SCT. Consumer behavioral actions of purchase satisfaction and repurchase add to the SCT behavior processes set, in which the pandemic denotes the environmental SCT aspect.

3.2. Consumer vulnerability

Smith and Cooper‐Martin (1997) define vulnerable consumers as those more prone to physical, psychological, and economic harm. When feeling vulnerable, for instance, when perceiving a threat, consumers strive to develop defensive actions, that is, engage in self‐protective behavior as a way of reducing adverse outcomes (Mehrolia et al., 2020). By relying on SCT, it can be assumed that consumer vulnerability denotes lower levels of self‐efficacy in an individual and that it calls for further consumer actions for empowerment.

Shi et al. (2017) argue that consumer vulnerability should consider several dimensions, such as product knowledge, product promotion, social pressure, refund policy, marketing and emotional pressure, and distinguish and purchase abilities. Most consumers are vulnerable in at least one dimension; a third of them can be vulnerable across many dimensions, while a lesser number of consumers can show no signs of vulnerability (Jourova, 2016). Similarly, Brennan et al. (2017) point out that consumer vulnerability should consider personal issues, individual characteristics, and external circumstances, since all of them affect the consumption experience. Hence, this study aims to fill this gap by focusing on the following dimensions: product knowledge, product promotion, and purchase and distinguish abilities.

3.3. Consumer resilience

Resilience can be defined as a stress‐coping ability and the capacity to recover quickly from difficult circumstances or failures; it refers to the individual trait of handling difficulty (Bonß, 2016; Ball & Lamberton, 2015; Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007; Connor & Davison, 2003). Therefore, resilience can be perceived as a self‐efficacy determinant, and self‐efficacy describes one’s capability of acquiring skills and believing in one’s own capability (Bandura, 1991) to cope with a change. As an integral part of the self‐regulation aspect, self‐efficacy has significant effect on motivation and action (Bandura, 1991). Following the same line of reasoning, it can be assumed that resilience plays an important role in one’s further actions. Given the consumer behavior context, actions can be explored in the form of purchase and/or repurchase.

Consumer resilience can be motivated by various factors such as personal (self), social (family and community), and (macro) environmental factors (Baker & Mason, 2012), and it influences the individual’s emotions, attitudes, and actions (Maddi, 2012). Since research on resilience is scarce, scholars (e.g., Ball & Lamberton, 2015) call for researching resilience as a key factor in consumption and an unrecognized element in consumer experience. It can be said that resilience research within the marketing disciplines is rare, although this concept is extremely relevant for marketing and consumer behavior (Rew & Minor, 2018).

4. HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Choudhury et al. (2019) point out that studies on vulnerability in terms of purchasing decision making are scarce. However, research on consumers at the base of the pyramid shows that low literacy, limited access to information, low information processing, and lack of resources can increase consumer vulnerability and constrain decision making (Choudhury et al., 2019). These notions indicate the potential negative effect of vulnerability on purchase experience, whereby vulnerability in terms of product knowledge (lack of it) might be relevant for decision making, that is, purchasing outcomes, such as satisfaction and repurchase. In addition, Shi et al. (2017) note that consumers might be vulnerable due to the lack of knowledge or experience with the products, which might result in behavioral pattern changes. Furthermore, consumers might be vulnerable because of their low literacy in terms of purchasing the wrong products and misinterpreting labels, and hence, reduced cognitive resources might negatively influence the purchase decisions (Stewart & Yap, 2020). Nevertheless, consumer experience and brand satisfaction depend on product knowledge (Fazal‐e‐Hasan et al., 2019). These notions lead to the assumption that the level of product knowledge, as a consumer vulnerability dimension, might be relevant for decision making and purchase satisfaction. Hence:

Hypothesis 1

Higher product knowledge positively influences purchase satisfaction.

Consumers can become vulnerable because of the lack of knowledge or skills related to marketplace options (Ringold, 2005). Their vulnerability might occur with regard to inadequate information or ineffective use of information, which can negatively affect the consumption decisions (Overall, 2004). Choudhury et al. (2019) stress the relevance of the moderating role of consumer vulnerability (as low‐literacy consumers, i.e., lacking information) in purchase decision making, which indicates the potential relevance of consumer vulnerability (product knowledge) for repurchase decision making. In addition, as product knowledge is important for the overall consumer experience and purchasing decisions (Fazal‐e‐Hasan et al., 2019), the validity of exploring its significance for repurchase decisions is strengthened as well. Considering these notions, along with the relevance of purchase satisfaction for repurchase intention (e.g., Elbeltagi & Agag, 2016; Rose et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011), it is reasonable to explore whether product knowledge influences repurchase intentions if mediated through purchase satisfaction. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2

Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of product knowledge on repurchase intention.

Vulnerability can occur when an individual interacts with stimuli, for instance, within the retail store, during product consumption, and when exposed to promotional messages (Baker et al., 2016). Perceived risk can make consumers feel vulnerable and promotional messages and advertising can reduce the perceived risk for consumers when buying products (Schiffman et al., 2012). Therefore, such reduced risk based on promotions can be considered a crucial factor for purchasing experience and satisfaction. Furthermore, some people (e.g., older ones) might be more vulnerable to unethical sales and telemarketing activities (Ford et al., 2019). These findings suggest that consumers might feel more or less vulnerable with respect to the offered promotional messages or the lack of them. Therefore, it can be assumed that promotional messages are crucial for a reduced level of consumer vulnerability due to sufficient information offered, which reduces consumers’ potential uncertainty when it comes to buying decision making and might stimulate purchase and/or satisfaction. Hence,

Hypothesis 3

Greater consumer proneness to product promotion positively influences purchase satisfaction.

No studies have investigated the impact of product promotion (as a consumer vulnerability dimension) on repurchase intention via purchase satisfaction in terms of our research context. However, some findings might indicate that this relationship is worth exploring. Namely, the study of the base of pyramid consumers (Choudhury et al., 2019) indicates that vulnerability in terms of low literacy and lack of information and/or resources might moderate the relationship between the received stimuli and consumer comprehension for the purchase decision‐making process. Other studies (e.g., Shalehah et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019) indicate that promotion efforts are important for repurchase decision making. Following a similar line of reasoning, product promotion, perceived as stimuli important in the context of consumer vulnerability, might be relevant for repurchase decision making. Given the notion that purchase satisfaction is a relevant precursor for repurchase decisions (Elbetagi & Agang, 2016; Rose et al., 2012), we assume that purchase satisfaction might mediate the influence of product promotion on repurchase intention. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of product promotion on repurchase intention.

Most individuals exert their free will through consumption, that is, selection of the products, whereby marketplace free will can be lost because of deterring conditions (Hill, 2019), thus leading to higher consumer vulnerability. In addition, consumers might be forced to endure restrictions on their desires, market spaces, and sources of satisfaction (Hill, 2019). Shi et al. (2017) indicate that consumers might experience emotional pressures when faced with different marketing stimulations, and may thus lack the ability to make proper purchasing decisions. Furthermore, consumers might be vulnerable because of their inability to seek alternatives because of the lack of purchasing experience (Glavas et al., 2020) and inadequate consumption access to resources (e.g., clothing, food, and healthcare) (Martin & Hill, 2012). This leads to the assumption that consumers might be vulnerable due to purchase inability given the marketing circumstances, such as the pandemic, and the consequent low offering or unavailability of products, which might affect their purchase and satisfaction during the pandemic. Hence,

Hypothesis 5

Higher purchase inability of the consumer negatively influences purchase satisfaction.

The way in which consumers manage stress and cope with adversity affects the balancing of their vulnerability, which influences consumption decision making (LaBarge & Pyle, 2020). Along with narrower purchasing choices, consumers might become vulnerable because of unethical retailers’ practices (Glavas et al., 2020), which can affect consumer purchase ability, consumer experience (e.g., satisfaction) with retailers, and their further decision making (e.g., repurchase). In addition, purchase satisfaction is an important factor in repurchase decision making (Elbeltagi & Agag, 2016; Rose et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, it is expected that purchase satisfaction might be relevant to the effect of consumer purchase ability on repurchase intention. Therefore, we posit:

Hypothesis 6

Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of purchase ability on repurchase intention.

Consumers might feel helpless when faced with an abundance of information, which tends to lower their capability to discriminate, that is, distinguish between similar products (Shi et al., 2017). Although some consumers who are unconsciously targeted by deceptive marketing practices may retain certain control of necessary resources and functioning in the marketplace (Hill & Sharma, 2020), the inability to comprehend marketing communication, for instance, due to low literacy, adds to their vulnerability (Stewart & Yap, 2020). If unable to distinguish among different products/brands and communication, consumers make mistakes and become vulnerable (Walsh et al., 2010). Hence, it could be concluded that when consumers are unable to distinguish relevant information, they cannot make appropriate purchase decisions, which might lower their purchase satisfaction. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 7

Lower distinguish ability of consumers negatively influences purchase satisfaction.

Although the marketplace can be threatening to consumers and increase their vulnerability (e.g., with low literacy or the inability to discriminate among similar stimuli) (Shi et al., 2017), some consumers can learn new ways of dealing with negative experiences (Stewart & Yap, 2020) and maintain control over their marketplace functioning (Hill & Sharma, 2020). Therefore, it can be assumed that some vulnerable consumers might rely on marketing efforts, and they might thus be forced to make purchase decisions, given the pandemic situation. In addition, if a certain level of purchase satisfaction is achieved in that sense, the same might be a valid reason for making other purchase decisions (e.g., repurchase), especially considering that purchase satisfaction is a precondition for repurchase intention (Elbeltagi & Agang, 2016; Rose et al., 2012). Moreover, some vulnerable consumers may endure less favorable outcomes from their service encounters (Glavas et al., 2020). If so, they might still be prone to making repurchase decisions in that particular situation. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 8

Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of distinguish ability on repurchase intention.

Although studies directly relating consumer resilience to consumer purchase satisfaction are lacking, resilience affects one’s actions (Maddi, 2012), and it is important in reducing conflict and achieving life and/or job satisfaction (Kossek & Perrigino, 2016). As resilience plays a vital role in decision making as an attempt to maintain functioning in an everyday context and to improve existing conditions, it covers social, economic, and environmental aspects (Connelly et al., 2017; Skondras et al., 2020). Translated into the consumer/retail context, it can be assumed that consumer resilience might be crucial for one’s functioning in terms of purchase decisions and achieving purchase satisfaction. In addition, consumers who feel resilient might be more efficient in coping with the pandemic when it comes to buying, and might thus make satisfactory purchasing decisions. Moreover, as a way of responding to stress, people can use different coping mechanisms and behavioral coping strategies as a way of achieving skillfulness and empowerment (Ford et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2021). These insights indicate the potential importance of consumer resilience in achieving empowerment in the form of satisfaction in the purchasing context. Furthermore, self‐efficacy is an important driver of behavioral processes (Thakur, 2018), which leads to the assumption that resilience, as a way of being self‐efficacious, might be an important driver of behavioral actions, such as purchase, resulting in a certain level of purchase satisfaction. Therefore, we expect that, given the circumstances, consumers that are more resilient might be more satisfied with the purchasing outcome as they handle adverse situations better (are more self‐efficacious) and are able to make purchase decisions. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 9

Consumer resilience positively influences purchase satisfaction.

Individuals adapt to adverse situations and accept the things that they are unable to change because this is the way of regaining control over their lives while achieving or maintaining their well‐being (LaBarge & Pyle, 2020). Following the same line of reasoning, although a pandemic situation is a circumstance that cannot be changed, people still need to buy, that is, make purchase decisions in order to meet their needs. Consumers who adapt (resilient ones) to this new situation and make satisfactory purchases might be prone to repurchase decisions. Furthermore, Stewart and Yap (2020) claim that low‐literacy consumers lack skills to acquire sufficient performance in typical consumption‐related tasks. However, if this notion is analogously applied to our context, it might indicate that high‐literacy consumers might be perceived as more resilient and capable (self‐efficacious) when performing consumption‐related tasks (e.g., repurchase). In addition, self‐efficacy and satisfaction positively influence continuance intention (Thakur, 2018). Hence, it can be assumed that resilience, perceived through determinant of self‐efficaciousness, might be a driver of repurchase (continuance) intention. In addition, given the relevance of purchase satisfaction for repurchase intention (e.g. Rose et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011), it seems worthwhile to explore the relationship between resilience and consumer action of repurchase through purchase satisfaction. Hence, it can be assumed that:

Hypothesis 10

Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of consumer resilience on repurchase intention.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has changed consumers’ priorities. According to Tam (2020), product availability is now a high priority, unlike brand loyalty; therefore, consumers are now more likely to buy a less familiar brand than wait for the first‐choice product to become available again. Thus, consumers’ future buying depends greatly on how brands and companies respond to pandemics and help them with this challenge (Tam, 2020). Following this notion, it could be expected that if consumers are satisfied with the retailers’ responses during the pandemic, they might stay with these retailers for future purchases. In addition, a significant number of studies have established that greater purchase satisfaction affects consumer repurchase intention positively (Elbetagi & Agang, 2016; Rose et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011). In general, repurchase intention can be positively affected by perceived value, loyalty, and customer satisfaction (Al‐Refaie et al., 2012; Vázquez‐Casielles et al., 2012). Considering the pandemic, it is projected that consumers will increase the frequency of purchasing from existing retailers (Dujić, 2020). Therefore, we can assume that consumers who are satisfied with their purchase from retailers chosen during the COVID‐19 pandemic will show positive repurchase intention in the future. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 11

Consumer purchase satisfaction positively influences repurchase intention.

The main changes that consumers undergo during crises are, among others, the needs for simplicity, smart consumption, temperance, and ethical consumption (Mansoor, 2011). The need for simplicity results in consumers’ willingness to adapt to limited choices and simplified demands for greater self‐efficacy utilization (Mansoor, 2011). The research context of the COVID‐19 pandemic represents a setting of limited choices and simplified demands, requiring a greater self‐efficacy level in order to acquire the needed goods. Moreover, consumers might be vulnerable due to the lack product knowledge (Ringold, 2005; Shi et al., 2017) and thus reduced the cognitive resources (Stewart & Yap, 2020), which might result in self‐efficacy and purchase behavior changes. Such changes, making consumers vulnerable, tend to also occur when interacting with promotional activities (Baker et al., 2016; Ford et al., 2019). In addition, when faced with pressures consumers might lack the ability to make proper purchasing decisions (Shi et al., 2017) including the search for alternatives (Glavas et al., 2020), and the ability to distinguish between products and retailers’ practices (Shi et al., 2017; Stewart & Yap, 2020; Walsh et al., 2010). Self‐efficacy in this context refers to the consumers’ level of adaptability to adverse situations. In our study, consumer adaptability as a self‐efficacy determinant is assessed as a consumer’s perception of a pandemic being an opportunity to learn new ways of buying. In other words, people tend to embrace technology more than ever in order to cope efficiently with isolation (Wright & Blackburn, 2020), and consumers who do not use the Internet, have poor computational skills, or are more risk averse might be more vulnerable (Jourova, 2016). However, consumer vulnerability across different dimensions can elicit a response in terms of adapting to new experiences (Baker et al., 2005) by employing defensive coping mechanisms (Hill & Sharma, 2020). Namely, consumers might strive to obtain control by seeking out new channels of consumption to meet their needs (Hill & Sharma, 2020). Hence, it makes sense that consumers facing the pandemic might strive to adapt to the current situation by learning to buy online in order to overcome their vulnerability in terms of product knowledge, product promotion, purchase and distinguish (in)abilities associated with purchasing. Therefore, we assume that higher consumer perception of the pandemic as an opportunity to learn new ways of buying might result in lowering consumer vulnerability across dimensions and strengthening its impact on purchase satisfaction. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 12

Consumer adaptability moderates the relationships between consumer vulnerability dimensions of (a) product knowledge, (b) product promotion, (c) purchase ability, and (d) distinguish ability and purchase satisfaction.

Consumer resilience can be considered a facilitator of change (Baker & Mason, 2012), whereby an individual’s behavior may shift when dealing with uncertainties (Voinea & Filip, 2011). Namely, consumers seek to change the status quo in order to gain greater control in their lives for both present and future situations (Voinea & Filip, 2011). Apparently, regaining control in life can be considered a recovery mechanism that might build resilience, while adaptability to new online buying means might assist. Predictions stating that the majority of consumers will continue shopping online and that they might find new online retailers instead of returning to the previous ones (Tam, 2020) can be considered to be indicative of consumers’ way to build resilience and a path toward achieving and retaining purchase satisfaction. Given the previous notions, we assume that higher consumer perception of the pandemic as an opportunity to learn new ways of buying might increase the impact of consumer resilience on purchase satisfaction. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 13

Consumer adaptability moderates the relationship between consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction.

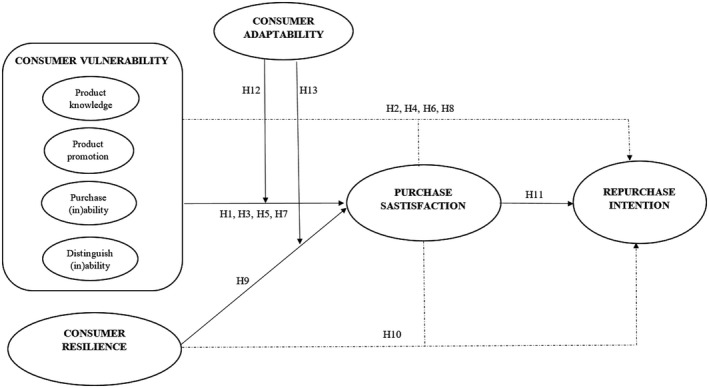

The research model presented in Figure 1. illustrates explored relationships.

FIGURE 1.

Research model of main, mediating and moderating effects

5. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

5.1. Sample and data collection

Empirical research was carried out on a convenience sample of 502 respondents from the Republic of Croatia. The online survey method was used, and the online questionnaire was developed using Qualtrics software. The survey link was distributed through personal email addresses and social network applications, such as WhatsApp, Viber, and Facebook. Data collection occurred from 05/25/2020 to 06/04/2020. Although probability samples are considered more generalizable, which is a limitation of convenience samples, the latter can be less expensive, more efficient, and simpler to execute, and they represent the norm within developmental science (Jager et al., 2017). In addition, convenience samples can provide better generalizability when homogeneous based on certain characteristics (Jager et al., 2017). We believe that the research context, that is, the current pandemic, adds to homogeneity and provides a slightly more generalizable setting. In other words, because all the respondents were exposed to the same environmental stimuli (the pandemic), it can be considered that the COVID‐19 setting is adding to the homogeneity of the target population. Given the notions (e.g. Bullen, 2014; Grimm, 2010; Szyrmer, 2015) that pretesting can be conducted with a smaller number of respondents (e.g., 5–10), especially when conducting customer studies (Szyrmer, 2015) and one‐to‐one analysis (Grimm, 2010), before conducting the survey, the questionnaire was pretested on 10 selected individuals (differing in age, education, and gender) to check for clarity and comprehension. In addition, these respondents were assessed as a small focus group, which offered us the possibility to obtain more detailed feedback owing to the questions asked in one‐to‐one communication (e.g., about understanding the questions and terminology, language flow, clarity of instructions and questions, provided/missing options, and duration). Sentences and options that were initially unclear were modified, presented to the respondents again, and finally included in the questionnaire. To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was checked by three marketing professors who helped modify certain items in order to attain better conceptual robustness.

The measurement instrument was a highly structured questionnaire for researching consumer attitudes and perceptions with respect to the explored concepts. The questionnaire also included demographic data of the respondents. Questionnaire items were translated from English to Croatian and then, retranslated into English. An English professor was assisted with this.

Upon collection, the data were checked for missing values, that is, incomplete surveys. There were 93 incomplete surveys, and these respondents/values were excluded from further analysis. By assessing the univariate outliers through Z‐score values (e.g., if > 3.29) and multivariate outliers through Mahalanobis distance (given the number of independent variables and degree of freedom), as suggested by Pallant (2011), four outliers (three univariate and one multivariate) were detected and then, excluded from further analysis. The final sample size was N = 405. The sample structure is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sample structure

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 291 | 71.9 |

| Male | 114 | 28.1 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 75 | 18.5 |

| 25–34 | 113 | 27.9 |

| 35–44 | 141 | 34.8 |

| 45–54 | 46 | 11.4 |

| 55–64 | 19 | 4.7 |

| 65–74 | 10 | 2.5 |

| 75–84 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary school | 2 | 0.5 |

| High school | 168 | 41.5 |

| College | 90 | 22.2 |

| University and higher | 145 | 35.8 |

| Total | 405 | 100 |

5.2. Measurement scales

The measurement scales were adapted from the relevant literature sources, as indicated below, whereby some items were modified to fit the research context better. These modifications refer to wording (i.e., formulating sentences). For instance, regarding the Connor and Davidson (2003) “Consumer resilience” scale, instead of using the original item of “In control of your life,” we formulated a slightly more complete sentence, “I think I am in control of my life.” This treatment was used for all resilience items.

The consumer vulnerability scale was adapted from Shi et al. (2017) and it included 11 items that referred to different dimensions of consumer vulnerability, such as product knowledge (three items), product promotion (three items), purchase ability (three items), and distinguish ability (two items). All items were rated on a 7‐point Likert scale (1–completely disagree, 2–disagree, 3–somewhat disagree, 4–neither agree nor disagree, 5–somewhat agree, 6–agree, and 7–completely agree). Product knowledge refers to consumers’ perceptions of whether the purchased product is safe; it includes consumers’ comparisons with other similar products and consumers’ knowledge of some other brand’s existence. The product promotion consumer vulnerability dimension refers to consumers’ assertions of buying advertised products, buying products based on the information received from mass media, and buying products recommended in promotional activities. Purchase (in)ability in terms of consumer vulnerability indicates that when buying, consumers frequently cannot find the required product and need to buy inferior/poorer ones. This dimension also indicates that consumers’ choices are narrowed, and that they are unable to buy what they desire and need to buy a replacement. Distinguish (in)ability means that, when buying, consumers are unaware of which information is fraudulent, and that during product consumption, they cannot tell which marketing methods are deceitful.

Consumer resilience encompassed seven items adapted from Connor and Davidson’s (2003) resilience scale. These items were measured on a Likert scale of seven degrees, along with the concept of satisfaction with the retailers, which was measured with four items. In terms of purchase satisfaction, three items were adapted from Wolter et al. (2017), Thomson (2006), and Chun and Davies (2006), while one item was developed by the authors. All items were measured on a 7‐point Likert scale. Repurchase intention (“I will continue to buy from the retailers I bought from during this pandemic”) was measured with an item developed by the author and it also included seven Likert degrees.

The moderating variable of consumers’ adaptability, that is, perceiving the pandemic situation as an opportunity for learning some new ways of buying, was assessed with the item “This pandemic situation represents an opportunity to learn some new (online) ways of buying” (not at all–1, in a lesser degree, not–2, in a higher degree, yes–3, and 4–completely yes). For the purpose of exploring the moderation effects, this variable was assessed together with independent variables as interaction terms (see Research results section).

All measurement scale items have been presented in a later section (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

CFA results

| Factor/items | Factor loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer vulnerability––product promotion | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.76 | |

| I often buy advertised products | 0.68 | |||

| I often buy based on the product information obtained from mass media (TV, radio, magazines, and so forth) | 0.72 | |||

| I usually buy products that are recommended in market promotion activities | 0.75 | |||

| Consumer vulnerability––purchase ability | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.73 | |

| When buying a product, I often have no alternative but to give up my first preference and choose another/worse one | 0.63 | |||

| When buying a product, I often realize that there are very few options within my ability | 0.70 | |||

| I am often unable to buy what I want and need to buy a similar substitute | 0.76 | |||

| Consumer vulnerability––distinguish ability | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.70 | |

| When buying a product, I usually do not know what information is fraudulent | 0.80 | |||

| Within the consumption process, I usually cannot tell which marketing method is fraudulent | 0.70 | |||

| Consumer resilience | 0.86 | 0.57 | 0.86 | |

| When things look hopeless, I never give up | 0.63 | |||

| When under pressure, I can focus and think clearly | 0.70 | |||

| I think of myself as a strong person | 0.88 | |||

| I can handle unpleasant feelings | 0.84 | |||

| I think I am in control of my life | 0.70 | |||

| Purchase satisfaction | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.92 | |

| I think that the market approach, of the companies from which I bought during the pandemic fulfilled my expectations | 0.80 | |||

| I am satisfied with my relationship with the companies from which I bought during the pandemic | 0.91 | |||

| I would recommend the companies from which I bought during the pandemic to others | 0.90 | |||

| My purchasing experience with companies from which I bought during the pandemic is very satisfying | 0.85 |

Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, composite reliability.

All standardize coefficients (factor loadings) are significant at p < .001.

6. RESEARCH RESULTS

When it comes to sample and researched variables, it can be said that the respondents showed an average level of general consumer vulnerability. When considering consumer vulnerability dimensions, they scored higher on distinguish and purchase ability dimensions, and lower on product promotion and product knowledge dimensions. Furthermore, the respondents seemed to be characterized by higher consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction levels. In addition, the respondents scored high on repurchase and low on adaptability to new (online) buying means/channels. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Variables | Mean | Standard deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer vulnerability (CV) (net) | 3.49 | 0.87 | 0.25 | −0.31 |

| CV (product knowledge) | 3.30 | 1.19 | 0.24 | −0.42 |

| CV (product promotion) | 3.34 | 1.27 | 0.19 | −0.75 |

| CV (purchase ability) | 3.55 | 1.26 | 0.16 | −0.85 |

| CV (distinguish ability) | 3.94 | 1.35 | −0.11 | −0.64 |

| Consumer resilience (CR) | 5.35 | 1.03 | −1.12 | 1.75 |

| Purchase satisfaction | 5.02 | 1.10 | −0.89 | 0.82 |

| Repurchase intention | 5.17 | 1.25 | −1.25 | 1.71 |

| Consumer adaptability | 1.82 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.30 |

Data were tested for normality of distribution (skewness, kurtosis–see Table 2; tolerance, variance inflation factor (VIF)), and (multi)collinearity (correlation analysis, multiple regression analyses). Collinearity diagnostics showed that the tolerance values ranged from 0.72 to 0.98, and VIF, from 1 to 1.38. These values are adequate, since tolerance should be > 0.10 and VIF < 10 (Pallant, 2011). Correlation analysis indicated the values (correlation coefficients) to be from 0.01 to 0.77. Performed tests confirmed the adequacy of the data (Pallant, 2011; Kline, 2011).

Additional descriptive analysis showed certain consumer behavior patterns (Table 3). Namely, it seems that not all consumers switched to online buying. A significant portion of the consumers bought goods online, while the rest retained their older habits of buying in physical stores.

TABLE 3.

Consumer behavior patterns

| Buying patterns | Share (%) |

|---|---|

| Did not buy online, but in‐store once a week | 47 |

| Bought online some products (e.g., clothes, shoes, electronics…) | 41 |

| Bought everything online | 7 |

| Asked others to buy for them (either online or offline) | 5 |

Regarding the categories of products, consumers mostly bought clothing and shoes online during the pandemic (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Online purchased products

| Products | Share (%) |

|---|---|

| Clothing and shoes | 52 |

| Food and beverages | 33 |

| Other (e.g., hygienic products, electronic equipment, cosmetics, books, games, and pet food) | 15 |

Regarding future purchases, a great number of consumers planned to continue buying online, while a significant number planned to return to their old (in‐store) buying habits (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Future buying intentions

| Future buying | Share (%) |

|---|---|

| Plan to continue buying online | 35.1 |

| Probably will buy online depending on the product category (e.g., clothes, shoes, and electronics) | 35.3 |

| Do not plan to continue purchasing online | 29.6 |

Considering the obtained results, the following can be briefly summarized:

More than 26% of the consumers felt vulnerable, while 27.4%, 33.2%, and 43.2% of the consumers felt vulnerable in terms of the product promotion dimension, purchase ability, and distinguish ability, respectively.

Up to 88.6% of the consumers felt resilient.

Given consumer adaptability, that is, perceiving the pandemic as an opportunity to acquire new (online) ways of buying, 83.5% of the consumers were not adaptable, while 16.5% were highly adaptable.

Up to 78.8% were satisfied with the retailers from which they bought during the pandemic, and more than 70% of the consumers planned to continue buying from these retailers in the future.

6.1. Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to test the reliability, validity, and unidimensionality of the measurement scales used, as well as to develop an adequate measurement model as a precondition for successful structural equation modeling (SEM). CFA and SEM were performed using SPSS AMOS 23, employing the maximum‐likelihood (ML) method and considering the analysis principles and thresholds suggested by relevant scholars within these fields (e.g., Bagozzi et al., 1991; Hair et al., 2010; Kline, 2011). The measurement model development was based on the following assumptions: each manifest variable loaded only on one factor, error terms were independent, and factors correlated. The first two assumptions, together with good model fit, refer to the unidimensionality measure. CFA analysis showed that not all items had significant factor loadings above the recommended threshold of > 0.60. This was the case with the consumer vulnerability product knowledge dimension (three items) and consumer resilience (two items). Because of the low factor loadings and the minimal two manifest variables needed per factor, these items were excluded from further analysis. This also required the exclusion of the product knowledge consumer vulnerability dimension from further CFA and SEM analyses. The CFA results are presented in Table 6.

As can be seen in Table 6, adequate CR and AVE values show that the measurement scales exhibit the characteristics of reliability and convergent validity. With respect to model fit, it can be stated that, after excluding low factor loading items (<0.6), the measurement model fits the data well (goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.95, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = 0.93, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.94, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.03, X 2 = 204.763, and df = 133). Hence, it can also be said that the measurement scales are unidimensional. Furthermore, the measurement scales show discriminant validity because the square roots of the AVE values are higher than the correlation values, as shown in Table 7.

TABLE 7.

Discriminant validity

| Factors | CV_PP | CV_PA | CV_DA | CR | PESAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV_PP | 0.72 | ||||

| CV_PA | 0.34** | 0.71 | |||

| CV_DA | 0.20** | 0.45** | 0.77 | ||

| CR | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.77 | |

| PESAT | 0.11* | −0.16** | −0.07 | 0.17** | 0.86 |

Abbreviations: CV_PP, consumer vulnerability––product promotion; CV_PA, consumer vulnerability––purchase ability; CV_DA, consumer vulnerability––distinguish ability; PESAT––purchase satisfaction.

Correlations significant at p < .05 level.

Correlations significant at p <.001 level.

Considering the previous discussion, it can be concluded that this measurement model is an adequate precondition for the structural model.

6.2. Structural equation modeling

The structural model (covariance based) was created by estimating the structural parameters using the ML method. For this purpose, three models, one constrained and two unconstrained models (see Table 8) were tested. Model 1 (constrained) included main effects, while mediating and moderating effects were fixed to 0. Model 2 (unconstrained) encompassed main and mediating effects with moderating effects fixed to 0, while in Model 3 (unconstrained) both mediating and moderating effects were freely estimated. Given significant model change, that is, chi‐square decrease (∆X2/∆D.F. = 10.537/8), hypotheses were tested based on Model 3 that shows acceptable fit values ((X 2 = 251.478 (df = 173), goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.947, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = 0.922, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.931, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.977, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.034)). The moderating effect of consumer adaptability on consumer vulnerability (product promotion, purchase, and distinguish (in)abilities)–purchase satisfaction and resilience–purchase satisfaction links was tested. Moderating effects were assessed as interactions terms of product promotion, purchase (in)ability, distinguish (in)ability, resilience. and consumer adaptability variables, which were mean‐centered prior to SEM analysis. The standardized structural coefficients are listed in Table 8.

TABLE 8.

SEM results

| Model 1 (Constrained model) | Model 2 (Unconstrained model) | Model 3 (Unconstrained model) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | Standard estimate | Standard estimate | Standard estimate |

| H3: Product promotion → purchase satisfaction | 0.248* | 0.246* | 0.242* |

| H5: Purchase (in)ability → purchase satisfaction | −0.322** | −0.318** | −0.307** |

| H7: Distinguish (in)ability → purchase satisfaction | 0.064 | 0.061 | 0.037 |

| H9: Consumer resilience → purchase satisfaction | 0.137** | 0.142** | 0.175** |

| H11: Purchase satisfaction → repurchase intention | 0.659* | 0.664* | 0.664* |

| Mediating effects | (ab) | (ab) | |

| H4: Purchase satisfaction mediating product promotion → repurchase intention | 0.163* | 0.160* | |

| H6: Purchase satisfaction mediating product ability → repurchase intention | −0.211** | −0.204** | |

| H8: Purchase satisfaction mediating distinguish ability → repurchase intention | 0.040 | 0.024 | |

| H10: Purchase satisfaction mediating consumer resilience → repurchase intention | 0.094** | 0.116** | |

| Moderating effects | |||

| H12b: Product promotion X Consumer adaptability → purchase satisfaction | 0.070 | ||

| H12c: Purchase ability X Consumer adaptability →purchase satisfaction | 0.043 | ||

| H12d: Distinguish ability X Consumer adaptability →purchase satisfaction | −0.006 | ||

| H13: Consumer resilience X Consumer adaptability →purchase satisfaction | 0.118** | ||

| Model properties | |||

| χ2/D.F. | 262.015/181 | 259.380/177 | 251.478/173 |

| ∆χ2/∆D.F. | 2.635/4 | 10.537/8 | |

| GFI | 0.945 | 0.946 | 0.947 |

| AGFI | 0.923 | 0.922 | 0.922 |

| NFI | 0.928 | 0.929 | 0.931 |

| CFI | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.977 |

| RMSEA | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.034 |

Effects are significant at p < .001 (*) and p < .05 (**). Since consumer vulnerability dimension of product knowledge did not show adequate validity within confirmatory factor analysis (factor loadings were < 0.50) it was removed from further analysis including SEM. Thus, the results for H1, H2, and H12a are not available and these hypotheses are rejected.

The SEM results (Table 8, Model 3) showed that consumer vulnerability affected purchase satisfaction differently, given its dimensions. Namely, only the dimensions of product promotion and purchase ability significantly directly affected purchase satisfaction, while the distinguish ability dimension did not influence purchase satisfaction. In addition, consumer resilience is a significant predictor of purchase satisfaction, while purchase satisfaction strongly affects the repurchase intention.

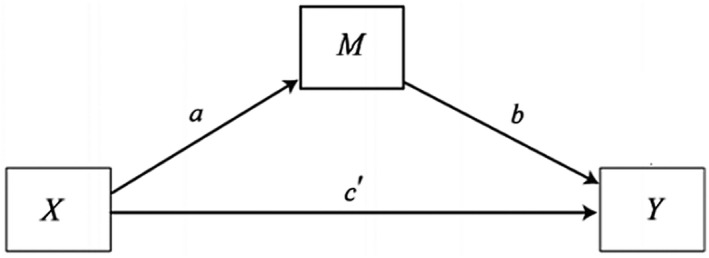

Considering mediation analysis, Baron and Kenny (1986) suggest conditions that need to be met to support the mediation: (1) the independent variable significantly influences dependent variable (c′), (2) independent variable significantly influences the mediator (a), and (3) mediator significantly influences dependent variable (b), whereby independent variable and mediator enter as predictors. Following Baron and Kenny’s (1986) conditions, our analysis does not meet the first condition. However, it should be noted that Baron and Kenny’s approach is seen as outdated and erroneous due to the ending the mediation analysis if the first condition is not met, which is unnecessarily restrictive condition (Memon et al., 2018). Namely, scholars (Hayes, 2018; Memon et al., 2018) suggest to be cautious and forward with the mediation analysis even if the mentioned condition (X Y) is not met, especially since this relationship is not a part of mediated effect (Memon et al., 2018). According to Hayes (2018), indirect effects (a, b, and ab) can be assessed even when direct effects (c′) are non‐significant, but are closer to zero than the total effects. This is the case in our study. Therefore, this provides a strong justification to continue with the mediation analysis following Hayes’ (2018) principles, whereby the mediating effects of consumer vulnerability (across dimensions of product promotion, purchase, and distinguish (in)abilities) and resilience on repurchase intention via purchase satisfaction were analyzed taking into account indirect (ab) and direct (c′) effects, as shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Mediation analysis (Hayes, 2018, p. 83)

The mediation analysis (Model 3) revealed that some consumer vulnerability dimensions, specifically product promotion (a = 0.242, p = .000) and purchase (in)ability (a = −0.307, p = .002), affected repurchase intention when mediated through purchase satisfaction (b = 0.664, p = .000). Consumer vulnerability dimension of distinguish ability (a = 0.037, p = .684) did not influence repurchase intention when mediated through purchase satisfaction. In addition, purchase satisfaction mediated the influence of consumer resilience (a = 0.175, p = .002) on repurchase intention. The established intermediate (ab) effects are presented in Table 9, whereby Model 2 (main and mediation effects) and Model 3 (main, mediating and moderating effects) are contrasted. Given chi‐square values, the model change from Model 1 to Model 2 is ∆X2/∆D.F. = 2.635/4 and from Model 2 to Model 3 is ∆X2/∆D.F. = 7.902/4.

TABLE 9.

Mediating effects

| Mediating effects | Direct effect (c′) | Indirect path (a) | Indirect path (b) | Indirect effects (ab) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| H4: Purchase satisfaction mediating product promotion → repurchase intention | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.246* | 0.242* | 0.664* | 0.664* | 0.163* | 0.160* |

| H6: Purchase satisfaction mediating product ability → repurchase intention | −0.035 | −0.036 | −0.318* | −0.307* | 0.664* | 0.664* | −0.211* | −0.204* |

| H8: Purchase satisfaction mediating distinguish ability → repurchase intention | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.061 | 0.037 | 0.664* | 0.664* | 0.040 | 0.024 |

| H10: Purchase satisfaction mediating consumer resilience → repurchase intention | −0.061 | −0.061 | 0.142 | 0.175* | 0.664* | 0.664* | 0.094* | 0.116* |

Significant relationships are marked with *; c′––independent variable → dependent variable/repurchase intention, a–independent variable → mediator/purchase satisfaction, b–mediator/purchase satisfaction → repurchase intention; ab–intermediate/indirect effects.

Furthermore, unlike consumer vulnerability (product promotion, purchase (in)ability, and distinguish (in)ability) and purchase satisfaction relationship, moderation analysis revealed that consumer adaptability moderates only the path/relationship between consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction. These results suggest that consumer adaptability to new online buying channels might help to increase resilient consumers’ purchase satisfaction.

Given the CFA and SEM results, and the applied SCT framework, the hypotheses’ statuses and brief summary of research results are presented in Table 10.

TABLE 10.

Hypotheses’ statuses

| Hypothesis | Status |

|---|---|

| H1: Higher product knowledge positively influences purchase satisfaction. | Rejected |

| H2: Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of product knowledge on repurchase intention. | Rejected |

| H3: Greater consumer proneness to product promotion positively influences purchase satisfaction. | Supported |

| H4: Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of product promotion on repurchase intention. | Supported |

| H5: Higher purchase inability of the consumer negatively influences purchase satisfaction. | Supported |

| H6: Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of purchase ability on repurchase intention. | Supported |

| H7: Lower distinguish ability of consumers negatively influences purchase satisfaction. | Rejected |

| H8: Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of distinguish ability on repurchase intention. | Rejected |

| H9: Consumer resilience positively influences purchase satisfaction. | Supported |

| H10: Purchase satisfaction mediates the influence of consumer resilience on repurchase intention. | Supported |

| H11: Consumer purchase satisfaction positively influences repurchase intention. | Supported |

| H12: Consumer adaptability moderates the relationships between consumer vulnerability dimensions of (a) product knowledge, (b) product promotion, (c) purchase ability, and (d) distinguish ability and purchase satisfaction. | Rejected |

| H13: Consumer adaptability moderates the relationship between consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction. | Supported |

|

Considering the obtained results and the applied theoretical framework (SCT), the research results can be briefly summarized as follows:

| |

7. DISCUSSION

7.1. Theoretical implications

Given the seriousness of the COVID‐19 crisis for both consumers and retailers, the main purpose of this study was to explore consumer behavior during the pandemic through the lens of the SCT framework. In this regard, the pandemic was assessed as an environmental SCT set; constructs of consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability are included in the personal processes SCT set and self‐efficacy subset, and purchase satisfaction and repurchase are included in the SCT behavioral processes set. In addition, the moderating effect of consumer adaptability on the relationships between vulnerability (product promotion, purchase, and distinguish (in)abilities), resilience, and purchase satisfaction was investigated, as well as the mediating effects of vulnerability dimensions and resilience on repurchase intention via purchase satisfaction. This study is the first to explore these processes in the proposed manner.

The research shows that, given the pandemic, consumers feel quite self‐efficacious when it comes to the effects of consumer vulnerability and resilience on purchase decision making (purchase satisfaction and repurchase). The research results indicate that product promotion, as an important consumer vulnerability dimension, is relevant for adequate decision making and thus positively influences purchase satisfaction, which also mediates the effect of product promotion on repurchase decisions. Hence, hypotheses H3 and H4 are supported. These findings are in accordance with existing notions that vulnerability can occur during promotion exposure and product consumption (Baker et al., 2016; Ford et al., 2019), and that promotional activities can reduce perceived risk (Schiffman et al., 2012), thus impacting consumer behavior. In addition, our results indicate that promotion efforts are important for repurchase decisions, as suggested by Zhou et al. (2019). Our findings also show that consumers feel more self‐efficacious if they can rely on product promotion to make purchase decisions, achieve purchase satisfaction, and plan repurchases under adverse circumstances. Thus, these findings contribute to the SCT environmental, personal, and behavioral processes sets.

Our study reveals that higher purchase inability, as one of the consumer vulnerability dimensions, negatively impacts purchase satisfaction, and that purchase satisfaction mediates the impact of purchase ability on repurchase intention. Therefore, hypotheses H5 and H6 are supported. These findings are aligned with some existing results indicating that when faced with emotional pressure, consumers might be unable to make proper purchase decisions (Shi et al., 2017) and may feel vulnerable if they lack alternatives (Glavas et al., 2020) or access to resources (Martin & Hill, 2012). In addition, our results corroborate LaBarge and Pyle’s (2020) notion that vulnerability affects consumption decision making (in our case, repurchase intention). Our findings indicate that consumers are able to become self‐efficacious (SCT personal processes set) if they can perceive the ability to buy, which consequently influences their behavioral processes of purchase satisfaction and repurchase (SCT behavioral processes set).

Regarding other consumer vulnerability dimensions and behavioral processes, no direct or indirect relationships were found between product knowledge and purchase satisfaction and repurchase owing to the lack of convergent validity of the product knowledge dimension. Therefore, hypotheses H1 and H2 were rejected. These relationships require further exploration because of the present insignificance. Furthermore, no relationship (direct or indirect) between distinguish ability and purchase satisfaction and repurchase was established; thus, hypotheses H7 and H8 were rejected. Further exploration of these effects is needed from the perspective of reasons for being unable to discriminate between products and stimuli and possibly consider the importance of product categories.

Considering consumer resilience, the research results indicate that resilience is an important factor in making purchase decisions in turbulent times. That is, it positively directly influences purchase satisfaction and indirectly influences repurchase intention if mediated via satisfaction. Hence, hypotheses H9 and H10 are supported. These results are in accordance with Maddi’s (2012) notion that resilience affects one’s actions. However, these results are novel in terms of the researched behavioral process of purchase satisfaction and repurchase, analyzing both direct and indirect effects, which has not been the case thus far. Our results confirm that consumers might strive to build their resilience as a type of coping strategy for achieving a sort of empowerment (as indicated by Ford et al., 2019), wherein the empowerment might be perceived in the form of purchase satisfaction and repurchase decisions. If resilience is considered a self‐efficacy determinant, then our findings of resilience affecting purchase satisfaction and repurchase corroborate Thakur’s (2018) notion that self‐efficacy is an important driver of behavioral processes. In addition, our findings confirm that in the context of pandemics (SCT environmental set), resilience can be perceived as an important SCT subset of self‐efficacy determinants crucial for SCT behavioral processes, such as purchase satisfaction and repurchase.

Furthermore, our research shows that purchase satisfaction positively influences repurchase intention. Therefore, H11 is supported. This result is in line with some existing findings suggesting that repurchase intention results from customer/purchase satisfaction (Elbeltagi & Agang, 2016; Rose et al., 2012; Vázquez‐Casielles et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2011). It corroborates indications that future buying will stem from an increased frequency of purchasing from existing retailers (Dujić, 2020), while greatly depending on the companies’ response and support during the pandemic (Tam, 2020). This result suggests that consumers who are satisfied with the purchase from the retailers they bought from during this pandemic are more likely to repurchase from these retailers in the future. In addition, this finding contributes to the SCT set of behavioral processes.

Consumer adaptability, in the form of perceiving the pandemic situation as an opportunity to learn new ways of buying, moderates some of the researched relationships. When it comes to consumer vulnerability, the moderating effect of consumer adaptability was not determined for the consumer vulnerability dimensions (product promotion, purchase (in)ability, and distinguish (in)ability) and purchase satisfaction relationship(s). Hence, hypothesis H12 is rejected. This finding is novel with respect to the researched context, that is, the pandemic and the moderating role of consumer adaptability, while adding to the SCT personal processes’ set. However, since insignificant, further exploration is needed, especially due to the existing notions suggesting that consumers could adapt to new buying channels as a way of regaining control over their lives as argued by Hill and Sharma (2020).

In addition, consumer adaptability, that is, perceiving the pandemic situation as an opportunity to learn new ways of buying, moderates the relationship between consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction. Our research suggests that consumer adaptability might help to increase resilient consumers’ purchase satisfaction. Hence, hypothesis H13 is supported. This finding is novel, but confirms the existing general notions, according to which consumer resilience might be considered a change facilitator (Baker & Mason, 2012) whereby consumer behavior might shift when facing uncertainty (Voinea & Filip, 2011). Additionally, the effect of consumer resilience on purchase satisfaction is increased when consumers are adaptable (self‐efficacious) to new online buying means. In addition to the novel moderating effect of consumer adaptability, this finding contributes to the SCT self‐efficacy and personal processes (sub)sets.

7.2. Managerial implications

In addition to its scientific contribution, this study has several managerial implications. Namely, marketers and retailers can better understand consumer behavior in the context of crisis as well as consumer pandemic coping capacities. They can gain awareness of consumers’ vulnerability and resilience levels and thus adapt their marketing and communication strategies for a better purchase experience (higher purchase satisfaction and repurchase). Given the research results, that is, significant effects of consumer vulnerability and resilience on purchase satisfaction and its influence on repurchase, the marketers need to build their strategy around consumer confidence, communicating appeals of trust and reassurance. In this way, they can help consumers feel more comfortable in their (online and offline) stores and encourage them to return.

Given the direct effects of vulnerability and resilience on purchase satisfaction and their indirect impacts on repurchase decisions via purchase satisfaction, it is essential to strive to provide a satisfactory purchase experience. For this purpose, marketers are advised to adopt the role of informing and educating consumers about the quality of products/services, the ways of acquiring the products during the crisis and post‐crisis, and the ability to cope with technological changes by communicating informational and educational appeals in their messages. Furthermore, they need to accentuate the accessibility and availability of products while communicating, thereby improving corporate dialog with consumers during their product promotion. This is important because it might stimulate consumers to become more self‐efficacious, that is, decrease the level of vulnerability (by increasing product promotion and purchase ability) and increase consumer resilience in market transactions, while enhancing the overall purchasing experience. In order to achieve this, marketers need to be present constantly in the media, that is, communicate with customers via both offline and online channels, in order to strengthen the image of their brands, improve consumer confidence, and provide assistive approach. It is essential to build trust and communicate the benefit (e.g., guarantee web store safety and privacy, security during the purchasing process), which can be done successfully using communication strategies (advertising and promotional activities), as previously suggested.

Given the moderating effect of consumer adaptability on the relationships between resilience and purchase satisfaction, companies should strive to improve the online purchasing experience and encourage online buying, which they can do by encouraging online purchasing in their communication messages. This might empower consumers, that is, make them feel more self‐efficacious, and reassure them when it comes to online buying safety, product availability, and creation of the positive perception that the pandemic can be perceived as an opportunity to acquire online buying skills. In this way, companies would be able to increase consumer resilience and enhance their overall purchasing experience, leading to satisfactory decision making in terms of purchase satisfaction and repurchase intention.

8. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

This study has some limitations. Although the sample was diverse throughout the country and encompassed different age and education groups, the convenience sampling method was used. However, the results are applicable only to those consumers faced with the “lockdown” and the pandemic purchasing experience, and therefore can be generalized to the Croatian population to a certain extent. Nevertheless, future research may replicate this study on a representative population of Croatian consumers. Another limitation of this study is the inability to analyze the product knowledge dimension of consumer vulnerability eventually because of the low CFA factor loadings and validity difficulties. Therefore, future studies may test this variable on other samples as well.

Since the COVID‐19 pandemic’s effects on retail vary in different countries because of different measures, future research might focus on other countries’ purchasing experiences, given the consumer vulnerability and resilience constructs. Cross‐cultural comparisons might provide interesting and helpful insights aimed at enhancing the overall consumer consumption experience. Future research might encompass additional personal variables, such as optimism, innovativeness, and anxiety/fear perceptions. It could also cover the other side of the purchasing context, that is, companies’ perspectives.

Given the marketing and pandemic context, this study is the first to explore the impacts of consumer vulnerability and resilience on purchase satisfaction and repurchase, encompassing the varying effect of consumer adaptability through the lens of SCT. In this regard, the findings contribute to assessing the SCT sets of environmental processes (pandemics), personal processes, and the self‐efficacy subset (consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability), and the behavioral processes set (purchase satisfaction and repurchase intention). This study reveals the differences in consumer vulnerability dimensions that directly affect purchase satisfaction and indirectly affect repurchase intention via purchase satisfaction by stressing the roles of product promotion and purchase ability in the decision‐making process. In addition, this study shows that consumers can be highly resilient in crisis and satisfied with their purchases, which might increase the chances of future repurchase decisions. This study also confirms that consumer adaptability is an important factor that influences the relationship between consumer resilience and purchase satisfaction. In addition, it can be said that it is crucial for companies to take appropriate actions in crises because they are the market agents that can empower consumers by decreasing their vulnerability and increasing their resilience, thus guiding consumers toward a positive purchase experience, that is, purchase satisfaction and repurchase.

Biography

Ivana Kursan Milaković is an Assistant professor at the Department of Marketing, at the University of Split, Faculty of Economics, Business and Tourism. She obtained Ph.D. in Economics in 2014. Her major interests include marketing and consumer behaviour. She has published in several international journals, such as International Journal of Advertising, the Service Industries Journal, and Electronic Commerce Research and Applications.