Abstract

The main protease of SARS‐CoV‐2 (Mpro), the causative agent of COVID‐19, constitutes a significant drug target. A new fluorogenic substrate was kinetically compared to an internally quenched fluorescent peptide and shown to be ideally suitable for high throughput screening with recombinantly expressed Mpro. Two classes of protease inhibitors, azanitriles and pyridyl esters, were identified, optimized and subjected to in‐depth biochemical characterization. Tailored peptides equipped with the unique azanitrile warhead exhibited concomitant inhibition of Mpro and cathepsin L, a protease relevant for viral cell entry. Pyridyl indole esters were analyzed by a positional scanning. Our focused approach towards Mpro inhibitors proved to be superior to virtual screening. With two irreversible inhibitors, azanitrile 8 (kinac/Ki=37 500 m −1 s−1, Ki=24.0 nm) and pyridyl ester 17 (kinac/Ki=29 100 m −1 s−1, Ki=10.0 nm), promising drug candidates for further development have been discovered.

Keywords: azapeptide nitriles, fluorogenic substrates, high throughput screening, pyridinyl 1H-indole-carboxylates, SARS-CoV-2 main protease

The main protease (Mpro) of SARS‐CoV‐2 has been recognized as a significant drug target to treat COVID‐19. The design of a new fluorogenic substrate, the recombinant expression of Mpro and the development of an HTS assay were combined with a structure‐based rational approach leading to the discovery of tailored azanitriles and indole pyridyl esters as novel, outstandingly potent Mpro inhibitors.

Introduction

Since December 2019, the outbreak of the current unprecedented coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) has led to a global crisis with increasing morbidity. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the pathogen of the pandemic, is a (+)ss‐RNA virus that shares the typical gene array of coronaviruses. It encodes two overlapping polyproteins from which the main protease (Mpro), also designated 3C‐like protease (3CLpro), is excised by autocleavage. The subsequent processing by SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro (and a second papain‐like protease, PLpro) is critical for the assembly of the viral replication–transcription complex, the release of functional viral proteins and thus for the replication of SARS‐CoV‐2. [1]

SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro has a strong preference for homodimerization. [2] Each protomer consists of three domains, out of which the chymotrypsin‐like domains I and II form a cleft harboring the substrate binding site. [3] Mpro is a cysteine protease with a noncanonical catalytic dyad composed of Cys145 residing in the S1′ site and His41 whose imidazole serves as a hydrogen bond donor to a structural water molecule. Cysteine proteases catalyze the hydrolysis of peptide bonds in the course of an acyl transfer mechanism. In the first step, accompanied by the release of the first product, an S‐acyl enzyme is formed as a result of the attack of the active site Cys145 on the carbonyl carbon of the scissile peptide bond. This covalent mechanism can be utilized for the design of inhibitors bearing an electrophilic warhead, susceptible for the nucleophilic attack of the catalytic cysteine.[ 3 , 4 , 5 ]

Mpro is highly conserved (96 % amino acid sequence identity) between SARS‐CoV‐2 and SARS‐CoV‐1, a related virus that caused severe acute respiratory syndromes worldwide in 2003. Due to the structural and functional similarities of both proteases, promising attempts towards new SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro inhibitors have been based on previous compounds targeting SARS‐CoV‐1 Mpro.[ 4 , 6 ] Examples include α‐ketoamide inhibitors which served as a starting point to expedite the identification of SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro inhibitors.[ 3 , 7 ] Mpro has a unique substrate specificity mainly recognizing the substrate residues ranging from P4 to P1′ and possessing a preference for glutamine at the P1 position. Such a feature is absent in human proteases suggesting the feasibility of developing selective protease inhibitors without toxicity in patients. Considering the seriousness of COVID‐19 and its implications on public life in lockdown mode and the economic fallout across the globe, there is an urgent unmet medical need to develop clinically effective SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific drugs, for which the viral proteases, Mpro and PLpro, represent attractive targets to combat viral replication and pathogenesis. [8]

In this study, we developed a new SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro assay for quantitative high‐throughput screening (HTS) and compared it to the current standard assay. Focused libraries were compiled taking inhibitors of related cysteine proteases and cysteine‐reactive compounds into account. As a second approach, virtual screening of a proprietary compound library [9] comprising 23 000 unique molecules was performed. We identified several candidate compounds and utilized the HTS results as a basis for structure‐based design, synthesis, and biochemical characterization of highly potent inhibitors for SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro.

Results and Discussion

As a first step, we established a bacterial expression system for SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro to be used in our biochemical assays. BL21 E. coli cells were transformed with a DNA construct encoding the protease with an N‐terminally fused Mpro cleavage site and a C‐terminal His10 tag linked via an HRV 3C protease cleavage site. During bacterial expression, Mpro autocatalytically cleaved the fusion protein, thereby generating the native Mpro N‐terminus. The His tag was employed to purify the enzyme and was subsequently cleaved off using an HRV 3C protease. After elimination of the latter protease utilizing its GST tag, the purified, native Mpro was obtained.

To monitor the proteolytic activity of His‐tagged Mpro, we applied an internally quenched fluorescent peptide substrate, Dabcyl‐Lys‐Thr‐Ser‐Ala‐Val‐Leu‐Gln‐Ser‐Gly‐Phe‐Arg‐Lys‐Met‐Glu(EDANS)‐NH2 (Figure S1, Supporting Information). [3] In the intact peptide, the quencher 4‐((4‐(dimethylamino)phenyl)azo)benzoic acid (Dabcyl) absorbs emission energy from the fluorophore, 5‐((2‐aminoethyl)amino)naphthalene‐1‐sulfonic acid (EDANS), which is disrupted by Mpro‐catalyzed cleavage of the peptide bond between the P1 amino acid glutamine and the P1′ amino acid serine resulting in a fluorescence signal. This substrate, referred to as “Dabcyl‐EDANS”, has recently been established for SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro.[ 3 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] It has been reported that a shorter, internally quenched fluorescent peptide substrate MCA‐Ala‐Val‐Leu‐Gln‐Ser‐Gly‐Phe‐Arg‐Lys(Dnp)‐Lys‐NH2 equipped with 7‐methoxy‐coumarin‐4‐yl‐acetic acid (MCA) as fluorophore and the 2,4‐dinitrophenyl (Dnp) quencher can also be used to monitor SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro.[ 4 , 14 , 15 ] Both internally quenched substrates share a P4‐to‐P4′ consensus sequence.

We designed a second type of fluorogenic substrate containing a C‐terminal 7‐amino‐4‐methylcoumarin (AMC) moiety. Its structure was based on the unique preference of Mpro for glutamine at the P1 position and the optimized P4‐to‐P2 sequence as previously determined using a positional scanning combinatorial library of natural and unnatural amino acids. [16] The synthesis of the resulting substrate, Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC, is depicted in Scheme S1. Very recently, a similar substrate was used for the development of activity‐based probes for SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro. [17]

By means of both substrates, Dabcyl‐EDANS and Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC, we established and optimized conditions for HTS assays with respect to the choice of buffer (Figure S2), the concentration of DMSO (Figure S3), as well as the correlation of Mpro concentration and product formation rate (Figure S4), and of the substrate concentration and gain of fluorescence upon complete cleavage (Figure S5). Expectedly and advantageously, product formation with the novel substrate Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC resulted in an improved readout (Figure S5). Under the established assay conditions (pH 7.2, 4 % DMSO), K m values of 60.6±3.6 μm for Dabcyl‐EDANS (literature values 28.2 μm at pH 6.5; 74.4 μm at pH 7.3)[ 10 , 12 ] and 48.2±5.6 μm for Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC have been determined (Figure S6; see Figure S7 for corresponding data with the purified native protease). Dabcyl‐EDANS exhibited a 10‐fold higher specificity constant of 5800 m −1 s−1 (literature values 3426 m −1 s−1, 5624 m −1 s−1)[ 3 , 10 ] than Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC (604 m −1 s−1). Hence, the extended structure of Dabcyl‐EDANS resulted in an accelerated turnover.

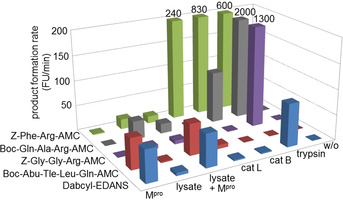

Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC was cleaved by Mpro much more efficiently than by cathepsin L, B, and trypsin, although these proteases have been employed at a concentration sufficient to convert three other selected substrates with very high rates (Figure 1). In contrast, Dabcyl‐EDANS was also hydrolyzed by trypsin, presumably after one of the basic amino acids of this substrate. HEK cell lysate of an appropriate protein concentration degraded the five substrates to a limited extent; a significant cleavage of Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC was not observed. Addition of Mpro to the lysate resulted in a pronounced Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC and Dabcyl‐EDANS cleavage only. At this stage, we considered Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC suitable to monitor Mpro activity for our HTS campaign on the search for inhibitors of this promising anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 target. Moreover, it can be expected to be an adequate substrate for measuring Mpro activity in a cellular environment, superior to the current, less selective standard substrate. The kinetic parameters of Mpro inhibition by selected inhibitors identified with Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC were found to be comparable to those from experiments with Dabcyl‐EDANS. Two reported inhibitors of Mpro, that is, disulfiram and ebselen, were initially investigated, and enzyme inhibition was confirmed (Table S2). We obtained similar IC50 values for disulfiram and somewhat higher ones for ebselen in comparison to the study of Jin et al., performed under different assay conditions. [14]

Figure 1.

Conversion of fluorogenic substrates by His‐tagged SARS‐CoV‐2 main protease (Mpro), lysate obtained from human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, HEK cell lysate spiked with Mpro, human cathepsin L (cat L), human cathepsin B (cat B), bovine trypsin, and in the absence of enzymes (FU, fluorescence units). The product formation was monitored for 10 min at 37 °C with an initial substrate concentration of 50 μm in all cases. Each enzyme was used at the same concentration in all respective experiments.

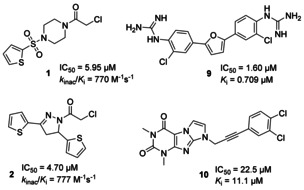

The first two in‐house libraries (Table 1) were compiled with respect to a potential electrophilic reactivity towards the active‐site cysteine nucleophile. Chloroacetamide derivatives (e.g. 1 and 2, Figure 2) were identified as irreversible Mpro inhibitors, and the second‐order rate constants of inactivation, k inac/K i, were determined to assess their potency (Table S1). Some Michael acceptors of the second library were weak irreversible Mpro inhibitors (Table S1), but the peptidic vinyl sulfones and acrylates of this library, known to inhibit other cysteine proteases, [18] were inactive. The third library was composed of compounds with a primary carboxamide, lactam, or imide moiety turning them into potential glutamine mimetics. However, hit compounds were not identified in this series.

Table 1.

Focused libraries for small‐molecule Mpro inhibitors[a]

|

library |

c [b] [μm] |

number of test compds |

number of hits[c] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

in‐house chloroalkyl derivatives |

50 |

29 |

7 |

|

in‐house Michael acceptors |

50 |

69 |

5 |

|

in‐house glutamine analogs |

50 |

33 |

0 |

|

in‐house carbonitriles |

50 |

186 |

17 |

|

natural product library |

10 |

143 |

2 |

|

Pathogen Box |

50 |

400 |

2 |

|

in‐house indoles |

10 |

78 |

0 |

|

virtually generated library |

10 |

140 |

1 |

[a] Residual activity of Mpro was measured with 50 μm Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC in 50 mm 3‐(N‐morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer, pH 7.2, 4 % DMSO at 37 °C. Reactions were monitored (λ ex=360 nm, λ em=460 nm) for 10 min and the progress curves were analyzed by linear regression. [b] Test concentration depended on compound solubilities and expected potencies. [c] Compounds which showed >50 % inhibition at the indicated concentration in duplicate measurements were considered as hits.

Figure 2.

Selected, confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro inhibitors identified by HTS. Compounds 1 and 2 were identified in the library of in‐house chloroalkyl derivatives (entry 1 in Table 1), compound 9 in the Pathogen Box library (entry 6 in Table 1), and compound 10 in the virtually generated library (entry 8 in Table 1).

The majority of the 186 members of the fourth library (Table 1) were peptide nitriles with a cyano group at the α‐carbon of the P1 amino acid, in place of the scissile peptide bond, which constitute prototypic inhibitors for cysteine proteases. [19] We discovered several hits in this library, mainly azapeptide nitriles, in which the cyano group was connected to a nitrogen replacing the P1 CαH unit (Table S1). The chemotype of azadipeptide nitriles had emerged as efficient inhibitors of human cysteine cathepsins, [20] as activity‐based probes for organelle‐specific delivery to lysosomal targets, and as PET‐imaging agents for tumor‐associated cathepsin activity. [21]

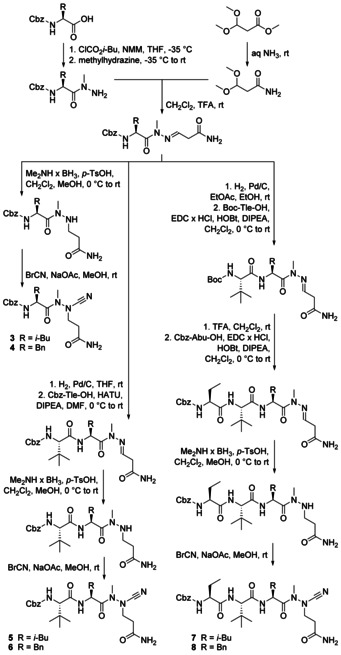

Since none of the azadipeptide nitriles contained the glutamine side chain and considering the respective primary specificity of SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro, we designed two peptidomimetics with this structural feature (Scheme 1). The synthetic route to compounds 3 and 4 involved the preparation of Cbz‐protected leucine‐ and phenylalanine‐derived hydrazides with methylated internal nitrogen to avoid heterocyclization of the envisaged products. [20] The precursor for the glutamine side chain was introduced as dimethyl acetal whose primary carboxamide moiety was generated from the corresponding methyl ester. Both fragments underwent condensation under acidic conditions. The resulting hydrazones were successfully hydrogenated with the dimethylamine–borane complex. [22] The following conversion with cyanogen bromide yielded the final azadipeptide nitriles 3 and 4 with aza‐glutamine in P1 and leucine or phenylalanine in P2 position, comprising the first examples of this chemotype with a functionalized P1 side chain.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the azapeptide nitriles 3–8.

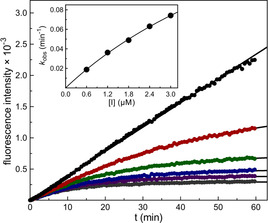

Similar to the well‐established dipeptide nitriles, azadipeptide nitriles undergo a covalent interaction with the target proteases by forming stabilized isothiosemicarbazide adducts. [20] Accordingly, 3 and 4 showed time‐dependent inhibition (Figure 3) and were analyzed as pseudo‐irreversible inhibitors of Mpro whose second‐order rate constants of inactivation k inac/K i are listed in Table 2 (see also Table S1). Both peptidic inhibitors were then structurally extended by the successive introduction of one or two amino acids as additional substrate specificity features of Mpro. Hence, we employed l‐tert‐leucine and l‐2‐aminobutyric acid as P3 and P4 building blocks (Scheme 1). The subsequent dimethylamine‐borane‐promoted reduction and the final electrophilic cyanation yielded 5 and 6, as well as 7 and 8, the first azatripeptide and azatetrapeptide nitriles described so far. Compounds 6, 7, and 8 exhibited strong inhibitory potency against SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro with k inac/K i values of more than 20 000 m −1 s−1 (Table 2, see also Figure S9). Phenylalanine in P2 was more advantageous than leucine, explicitly in case of the azatripeptides (5 versus 6). The two azatetrapeptide nitriles 7 and 8 showed similar K i values (23.5 nm and 24.0 nm), but 8 had a faster inactivation step (Table S1).

Figure 3.

Mpro‐catalyzed hydrolysis of 50 μm (=1.03×K m) of Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC in the absence (black) or presence of increasing concentrations of inhibitor 4 (from top to bottom: 0.6 μm, 1.2 μm, 1.8 μm, 2.4 μm, 3.0 μm). Inset: A plot of first‐order rate constants versus the inhibitor concentrations and non‐linear regression gave a k inac/K i value of 1150 m −1 s−1.

Table 2.

Mpro inhibition by azapeptide nitriles with aza‐glutamine in P1 position[a]

|

compd |

P4 |

P3 |

P2 |

k inac/K i [m −1 s−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 |

– |

– |

Cbz‐Leu |

489 |

|

4 |

– |

– |

Cbz‐Phe |

1150 |

|

5 |

– |

Cbz‐Tle |

Leu |

2060 |

|

6 |

– |

Cbz‐Tle |

Phe |

36 000 |

|

7 |

Cbz‐Abu |

Tle |

Leu |

21 400 |

|

8 |

Cbz‐Abu |

Tle |

Phe |

37 500 |

[a] Progress curves in the presence of five different inhibitor concentrations and 50 μm Boc‐Abu‐Tle‐Leu‐Gln‐AMC in 50 mm MOPS buffer, pH 7.2, 4 % DMSO at 37 °C were monitored for 60 min and analyzed by non‐linear regression using the equation [P]=v i×(1−exp(−k obs×t)/k obs+d. Values k inac/K i were determined by non‐linear regression using the equation k obs=(k inac×[I])/([I]+K i×(1+[S]/K m)). Deviation of each data point from the calculated non‐linear regression was less than 10 %.

The structural expansion (3 and 4 versus 5 and 6 versus 7 and 8) resulted in improved biological activity confirming that such compounds gain their potency not only from covalent binding, [23] but also from specific noncovalent interactions of the P1–P4 residues with the active‐site subsites. To further rationalize the impressive activity of 8 (k inac/K i=37 500 m −1 s−1, K i=24.0 nm), we performed a covalent docking using the X‐ray crystal structure of the SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro in complex with a peptidic acrylate inhibitor (Figures 4 and S15). [14]

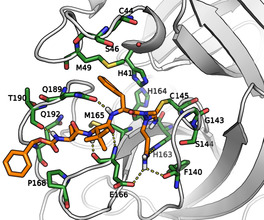

Figure 4.

Predicted binding pose of the azapeptide nitrile 8 (orange) in the active site of SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro with relevant amino acids (green). The model was obtained based on a reported enzyme–inhibitor complex (PDB ID: 6LU7). [14] The covalent bond between the sulfur of the active site Cys145 and the cyano carbon of the warhead generated an isothiosemicarbazide‐type enzyme‐inhibitor adduct. The P1 glutamine side chain resides in the S1 pocket. The aromatic ring of the P2 phenylalanine is positioned in the hydrophobic S2 pocket (His41, Met49, Met165) in proximity to the Gln189 side chain. The P3 tert‐leucine is oriented towards the solvent. The P4 aminobutyric acid and the N‐terminal, Cbz‐capped part of the inhibitor are oriented towards the S3/S4 region. Hydrogen bond interactions are shown in yellow dotted lines, for details see Figure S15. The binding mode of 8 is consonant with X‐ray crystal structures of other peptidic inhibitors in complex with Mpro.[ 4 , 10 , 14 ]

Out of a natural product library of 143 members, two compounds were initially identified as hits (Table S1), but could not be confirmed by subsequent concentration‐dependent inhibition curves. Testing of the Pathogen Box (a collection of anti‐Malaria agents) [24] yielded an Mpro inhibiting bis‐benzguanidine (compound 9, Figure 2). Moreover, we performed a virtual screening (for details, see Supporting Information) of our PharmaCenter Bonn compound library, which provided the active 1H‐imidazo[1,2‐f]purine derivative 10 as a single hit (Figure 2). In contrast, preparation and structural optimization of reported SARS‐CoV‐1 Mpro inhibitors was highly successful, highlighted by the class of pyridyl indole esters. [25]

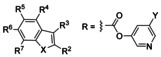

Such esters preferentially contained a chloro‐substituted pyridinolic group and were also active against the related hepatitis A virus 3C and human rhinovirus 3C proteinases. [26] This structural feature was a prerequisite for SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro inhibition, since a library of different indoles [27] did not offer any hit (Table 1). To explore the chemical space of indole esters, a positional scanning of the ester substituent at the indole core was conducted (Table 3). For this purpose, the complete set of 1H‐indolecarboxylic acids was converted by uronium salt‐mediated reactions with halo‐substituted pyridin‐3‐ols to yield 11–18 (Schemes S3 and S4). These esters were kinetically analyzed as irreversible inhibitors of Mpro (Table 3; see also Table S1 and Figure S10). All the isomeric esters 11–16 exhibited strong Mpro inhibitory activity; their second‐order rate constants of inactivation differed by one order of magnitude, and the ester moiety at position 7 (compound 16) resulted in the strongest Mpro inactivation. The replacement of chlorine by bromine led to a further improvement (13, Y=Cl versus 18, Y=Br). Strikingly, the introduction of a chloro substituent at position 5 (compare 11, R5=H versus 17, R5=Cl) provided the most potent inhibitor of this series, the new indole ester 17 (k inac/K i=29 100 m −1 s−1, K i=10.0 nm). The observed time‐dependent inhibition indicated that these indole esters act by acylation of the active‐site cysteine (see also Figure S16), in accordance with literature data.[ 25 , 26 ] While the majority of indole esters (11–19), could be characterized as efficient pseudo‐irreversible inhibitors, some (Table S1) showed enzyme reactivation within a period of one hour (e.g. Figure S11) due to hydrolytic cleavage of the acyl‐enzyme formed. Bioisosteric replacement of the indole moiety (X=NH, Table 3) by a benzofuran ring system (X=O, Table 3) in 20 led to an inhibitor with high affinity (IC50=5.41 nm) but pronounced Mpro reactivation. We analyzed the structure–activity relationships of irreversibly acting indole esters with the same 5‐chloropyridin‐3‐olate leaving group (X=NH, Y=Cl; 11–17, 19). Their inhibitory potency did not correlate with the susceptibility to nucleophilic attack, which could be derived from the acidity of the corresponding acids (Figure S12). [28] This finding clearly revealed the importance of specific protease–inhibitor interactions for Mpro inhibition by indole esters.

Table 3.

Mpro inhibition by 5‐halopyridin‐3‐yl 1H‐indole‐carboxylates[a,b]

|

compd |

X |

R2 |

R3 |

R4 |

R5 |

R6 |

R7 |

Y |

k inac/K i [m −1 s−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

11 |

NH |

R |

H |

H |

H |

H |

H |

Cl |

7600 |

|

12 |

NH |

H |

R |

H |

H |

H |

H |

Cl |

6090 |

|

13 |

NH |

H |

H |

R |

H |

H |

H |

Cl |

14 800 |

|

14 |

NH |

H |

H |

H |

R |

H |

H |

Cl |

3200 |

|

15 |

NH |

H |

H |

H |

H |

R |

H |

Cl |

4400 |

|

16 |

NH |

H |

H |

H |

H |

H |

R |

Cl |

20 200 |

|

17 |

NH |

R |

H |

H |

Cl |

H |

H |

Cl |

29 100 |

|

18 |

NH |

H |

H |

R |

H |

H |

H |

Br |

24 000 |

|

19 |

NH |

‐(CH2)4‐ |

H |

R |

H |

H |

Cl |

5620 |

|

|

20 |

O |

R |

H |

H |

H |

H |

H |

Cl |

n.d.[c] |

[a] Syntheses are described in Supporting Information. [b] For kinetic analysis, see Table 2. [c] n.d.: not determined. IC50=5.41 nm.

The potent pyridyl indolecarboxylates with their molecular weight of less than 300 g mol−1 can even be regarded as fragments. Nevertheless, some of them are amazingly potent Mpro inhibitors with IC50 values in the low nanomolar concentration range (Table S1) along with k inac/K i values of up to almost 30 000 m −1 s−1. Thus, these compounds have high ligand efficiency, which makes them excellent scaffolds for drug development. Very recently, the indole ester 13, which displayed intermediate Mpro inhibitory potency, and the related 5‐chloropyridin‐3‐yl dihydroindole‐4‐carboxylate were demonstrated to be active against the infectivity and replication of SARS‐CoV‐2 in Vero E6 cells, [29] indicating the high therapeutic potential of this class of compounds.

Selected members of both classes of extraordinarily potent Mpro inhibitors, azapeptide nitriles 4, 6, and 8, and halopyridyl esters 16, 17, and 20, were additionally investigated for their potency in Mpro‐containing cell lysates. In fact, all of the investigated inhibitors displayed similarly high Mpro inhibition in HEK and human lung epithelial A549 cell lysates as in buffer containing the purified enzyme, showing virtually complete inhibition at 1 μm (6, 8, 16, 17, 20) or at 10 μm (4), respectively (Figure S14). These results indicate that the new Mpro inhibitors retain full activity in a cellular context.

For cell entry, coronaviral spike proteins bind to cellular receptors and are primed by host cell proteases. Cathepsin L, a human lysosomal cysteine protease, contributes to the proteolytic activation of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein in the endosomal–lysosomal compartment. [30] Hence, it was suggested to develop dual inhibitors which target the viral protease and the host cathepsin L. [11] We therefore investigated the potential of selected compounds as dual targeting inhibitors (Table S3). While the indole esters (e.g. 13 and 17) did not inhibit cathepsin L (and the related enzyme cathepsin B) indicating selectivity of this chemotype for viral cysteine proteases, our azapeptide nitriles 6, 7, and 8 exhibited strong anti‐cathepsin L activity with K i values of 53 nm, 22 nm and 120 nm, respectively, (Table S3), thus turning them into particularly interesting cysteine protease inhibitors, acting at different stages of virus replication.

Conclusion

Since SARS‐CoV‐2 Mpro plays an irreplaceable role in the life cycle of the virus, its inhibition by low‐molecular weight drug candidates has been recognized as a promising strategy against COVID‐19. We developed a new, readily available specific substrate that is directly applicable for HTS and can even be used in cell lysates to test for Mpro activity. This report highlights the successful discovery of highly potent Mpro inhibitors out of several focused libraries. Based on the identification of appropriate substructures, two types of molecules have been assembled, peptidomimetic azatripeptide and azatetrapeptide nitriles as well as non‐peptidic halopyridinyl 1H‐indole‐carboxylates. These rationally designed inhibitors are promising candidates for further development with the ultimate goal of attaining antiviral drugs against COVID‐19.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the BMBF for funding our graduate research school BIGS DrugS, and to Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) for providing the Pathogen Box for screening. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

J. Breidenbach, C. Lemke, T. Pillaiyar, L. Schäkel, G. Al Hamwi, M. Diett, R. Gedschold, N. Geiger, V. Lopez, S. Mirza, V. Namasivayam, A. C. Schiedel, K. Sylvester, D. Thimm, C. Vielmuth, L. Phuong Vu, M. Zyulina, J. Bodem, M. Gütschow, C. E. Müller, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 10423.

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Michael Gütschow, Email: guetschow@uni-bonn.de.

Prof. Dr. Christa E. Müller, Email: christa.mueller@uni-bonn.de.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D., J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 418–423; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Gorbalenya A. E., Baker S. C., Baric R. S., de Groot R. J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A. A., Haagmans B. L., Lauber C., Leontovich A. M., Neuman B. W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L. L., Samborskiy D. V., Sidorov I. A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J., Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. El-Baba T. J., Lutomski C. A., Kantsadi A. L., Malla T. R., John T., Mikhailov V., Bolla J. R., Schofield C. J., Zitzmann N., Vakonakis I., Robinson C. V., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 23544–23548; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 23750–23754. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R., Science 2020, 368, 409–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dai W., Zhang B., Jiang X. M., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Peng J., Liu F., Li C., Li Y., Bai F., Wang H., Cheng X., Cen X., Hu S., Yang X., Wang J., Liu X., Xiao G., Jiang H., Rao Z., Zhang L. K., Xu Y., Yang H., Liu H., Science 2020, 368, 1331–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Pillaiyar T., Manickam M., Namasivayam V., Hayashi Y., Jung S. H., J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 6595–6628; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Gehringer M., Laufer S. A., J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5673–5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pillaiyar T., Meenakshisundaram S., Manickam M., Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25, 668–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang L., Lin D., Kusov Y., Nian Y., Ma Q., Wang J., von Brunn A., Leyssen P., Lanko K., Neyts J., de Wilde A., Snijder E. J., Liu H., Hilgenfeld R., J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 4562–4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Capasso C., Nocentini A., Supuran C. T., Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 10.1080/13543776.2021.1857726; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Welker A., Kersten C., Müller C., Madhugiri R., Zimmer C., Müller P., Zimmermann R., Hammerschmidt S., Maus H., Ziebuhr J., Sotriffer C., Schirmeister T., ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 340–354; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Petushkova A. I., A. A. Zamyatnin, Jr. , Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.pharmchem1.uni-bonn.de/www-en/pharmchem1-en/mueller-laboratory/compound-library.

- 10. Ma C., Sacco M. D., Hurst B., Townsend J. A., Hu Y., Szeto T., Zhang X., Tarbet B., Marty M. T., Chen Y., Wang J., Cell Res. 2020, 30, 678–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sacco M. D., Ma C., Lagarias P., Gao A., Townsend J. A., Meng X., Dube P., Zhang X., Hu Y., Kitamura N., Hurst B., Tarbet B., Marty M. T., Kolocouris A., Xiang Y., Chen Y., Wang J., Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabe0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhu W., Xu M., Chen C. Z., Guo H., Shen M., Hu X., Shinn P., Klumpp-Thomas C., Michael S. G., Zheng W., ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 1008–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Hoffman R. L., Kania R. S., Brothers M. A., Davies J. F., Ferre R. A., Gajiwala K. S., He M., Hogan R. J., Kozminski K., Li L. Y., Lockner J. W., Lou J., Marra M. T., L. J. Mitchell, Jr. , Murray B. W., Nieman J. A., Noell S., Planken S. P., Rowe T., Ryan K., G. J. Smith 3rd , Solowiej J. E., Steppan C. M., Taggart B., J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 12725–12747; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Ghahremanpour M. M., Tirado-Rives J., Deshmukh M., Ippolito J. A., Zhang C. H., Cabeza de Vaca I., Liosi M. E., Anderson K. S., Jorgensen W. L., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2526–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L. W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H., Nature 2020, 582, 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. Coelho C., Gallo G., Campos C. B., Hardy L., Würtele M., PLoS One 2020, 15, e0240079; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Li Z., Li X., Huang Y. Y., Wu Y., Liu R., Zhou L., Lin Y., Wu D., Zhang L., Liu H., Xu X., Yu K., Zhang Y., Cui J., Zhan C. G., Wang X., Luo Hai-B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27381–27387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rut W., Groborz K., Zhang L., Sun X., Zmudzinski M., Pawlik B., Wang X., Jochmans D., Neyts J., Młynarski W., Hilgenfeld R., Drag M., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van de Plassche M. A. T., Barniol-Xicota M., Verhelst S. H. L., ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 3383–3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Breuer C., Lemke C., Schmitz J., Bartz U., Gütschow M., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2008–2012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Mertens M. D., Schmitz J., Horn M., Furtmann N., Bajorath J., Mareš M., Gütschow M., ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 955–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Frizler M., Stirnberg M., Sisay M. T., Gütschow M., Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 294–322; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Cianni L., Feldmann C. W., Gilberg E., Gütschow M., Juliano L., Leitão A., Bajorath J., Montanari C. A., J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 10497–10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. Löser R., Frizler M., Schilling K., Gütschow M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4331–4334; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 4403–4406; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Frizler M., Lohr F., Lülsdorff M., Gütschow M., Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 11419–11423; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Frizler M., Schmitz J., Schulz-Fincke A. C., Gütschow M., J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5982–5986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Yang P. Y., Wang M., Li L., Wu H., He C. Y., Yao S. Q., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6528–6541; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Loh Y., Shi H., Hu M., Yao S. Q., Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 8407–8409; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Löser R., Bergmann R., Frizler M., Mosch B., Dombrowski L., Kuchar M., Steinbach J., Gütschow M., Pietzsch J., ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 1330–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Casarini M. E., Ghelfi F., Libertini E., Pagnoni U. M., Parsons A. F., Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 7925–7932. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frizler M., Lohr F., Furtmann N., Kläs J., Gütschow M., J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duffy S., Sykes M. L., Jones A. J., Shelper T. B., Simpson M., Lang R., Poulsen S. A., Sleebs B. E., Avery V. M., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00379-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Zhang J., Pettersson H. I., Huitema C., Niu C., Yin J., James M. N., Eltis L. D., Vederas J. C., J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 1850–1864; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Ghosh A. K., Gong G., Grum-Tokars V., Mulhearn D. C., Baker S. C., Coughlin M., Prabhakar B. S., Sleeman K., Johnson M. E., Mesecar A. D., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5684–5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.

- 26a. Huitema C., Zhang J., Yin J., James M. N., Vederas J. C., Eltis L. D., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 5761–5777; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26b. Im I., Lee E. S., Choi S. J., Lee J. Y., Kim Y. C., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 3632–3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.

- 27a. Pillaiyar T., Gorska E., Schnakenburg G., Müller C. E., J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 9902–9913; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27b. Baqi Y., Pillaiyar T., Abdelrahman A., Kaufmann O., Alshaibani S., Rafehi M., Ghasimi S., Akkari R., Ritter K., Simon K., Spinrath A., Kostenis E., Zhao Q., Köse M., Namasivayam V., Müller C. E., J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 8136–8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keenan S. L., Peterson K. P., Peterson K., Jacobson K., J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85, 558–560. [Google Scholar]

- 29.

- 29a. Hattori S. I., Higshi-Kuwata N., Raghavaiah J., Das D., Bulut H., Davis D. A., Takamatsu Y., Matsuda K., Takamune N., Kishimoto N., Okamura T., Misumi S., Yarchoan R., Maeda K., Ghosh A. K., Mitsuya H., mBio 2020, 11, e01833-20; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29b. Hattori S. I., Higashi-Kuwata N., Hayashi H., Allu S. R., Raghavaiah J., Bulut H., Das D., Anson B. J., Lendy E. K., Takamatsu Y., Takamune N., Kishimoto N., Murayama K., Hasegawa K., Li M., Davis D. A., Kodama E. N., Yarchoan R., Wlodawer A., Misumi S., Mesecar A. D., Ghosh A. K., Mitsuya H., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.

- 30a. Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T. S., Herrler G., Wu N. H., Nitsche A., Müller M. A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S., Cell 2020, 181, 271–280; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30b. Shang J., Wan Y., Luo C., Ye G., Geng Q., Auerbach A., Li F., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30c. Liu T., Luo S., Libby P., Shi G. P., Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 213, 107587; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30d. Alexander S. P., Armstrong J. F., Davenport A. P., Davies J. A., Faccenda E., Harding S. D., Levi-Schaffer F., Maguire J. J., Pawson A. J., Southan C., Spedding M., Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 4942–4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary