Abstract

Background

The novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19) hinders the treatment of non‐COVID illnesses like cancer, which may be pronounced in lower‐middle‐income countries.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study audited the performance of a tertiary care surgical oncology department at an academic hospital in India during the first six months of the pandemic. Difficulties faced by patients, COVID‐19‐related incidents (preventable cases of hospital transmission), and modifications in practice were recorded.

Results

From April to September 2020, outpatient consultations, inpatient admissions, and chemotherapy unit functioning reduced by 62%, 58%, and 56%, respectively, compared to the same period the previous year. Major surgeries dropped by 31% with a decrease across all sites, but an increase in head and neck cancers (p = .012, absolute difference 8%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.75% — 14.12%). Postoperative complications were similar (p = .593, 95% CI: −2.61% — 4.87%). Inability to keep a surgical appointment was primarily due to apprehension of infection (52%) or arranging finances (49%). Two COVID‐19‐related incidents resulted in infecting 27 persons. Fifteen instances of possible COVID‐19‐related mishaps were averted.

Conclusions

We observed a decrease in the operations of the department without any adverse impact in postoperative outcomes. While challenging, treating cancer adequately during COVID‐19 can be accomplished by adequate screening and testing, and religiously following the prevention guidelines.

Keywords: cancer surgery, coronavirus, COVID‐19, developing countries, low‐income countries, low‐middle‐income countries, surgery, surgical oncology

1. BACKGROUND

The novel coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID‐19) has precipitated the world into an unprecedented global crisis. 1 , 2 Healthcare systems all over the world have nearly collapsed in providing the necessary care for this vast burden of sick patients. As a consequence, emergency and elective care of non‐COVID patients have been drastically impacted. Logistics have been adversely affected, with an ensuing diversion of resources causing severe roadblocks in managing other major health issues like cancer.

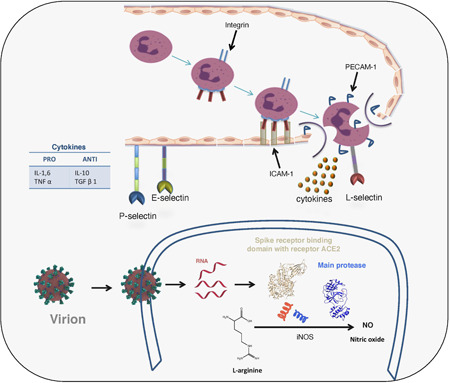

Surgery is one of the cornerstones of oncological management. However, for a disease that primarily involves the lung parenchyma with consequent inflammation (Figure 1) leading to nearly every sixth patient developing acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary function is adversely impacted leading to a further hindrance in performing surgery. 3 , 4 As a large tertiary care teaching institute, our centre has been shouldering, along with others, the responsibilities of managing COVID‐19 in India's most populous state catering to a populace of 200 million. Nationwide and state lockdowns which were initiated in the later part of March 2020 prevented patients from reaching the hospital. For patients with cancer, where appropriate and timely surgery is vital for achieving good outcomes, this is likely to have serious repercussions.

Figure 1.

Acute inflammation and the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

It is quintessential to continue care of the cancer patients even during a pandemic. Nevertheless, this care must not compromise the safety of patients and healthcare professionals. We have walked through these turbulent times with utmost safety and care. Time has taught us several lessons, and we have continuously modified our approach to minimise the recurrence of such adverse events. This paper describes our experience during the first 6 months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, including the functioning of our department, clinical outcomes, the problems faced by the patients, and the lessons learnt during this period.

2. METHODS

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Department of Surgical Oncology at an academic university hospital in north India. Being one of the oldest surgical oncology departments in India, we considered it our responsibility and continued cancer care during this pandemic. We have a prospectively maintained structured database of patients presenting in the department for receiving treatment. In this study, we included all patients that received any form of treatment at the Department of Surgical Oncology in the last 6 months, during the COVID‐19 pandemic (April to September 2020) including outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, chemotherapy, and major and minor surgical procedures. Only patients with a histopathology or cytopathology proven malignancy were included. All procedures were carried out per the principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki, following the international guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The institutional ethics committee allowed a waiver of formal approval in light of the retrospective nature of the study and the ongoing pandemic situation.

Details of outpatient attendance, teleconsultations, total inpatient admissions, major and minor surgical procedures were recorded. Mortality, morbidity, and COVID‐19 infection in patients were recorded. We compared this data with six months of our pre‐COVID‐19 average clinical work from the same period of last year (April to September 2019). We also audited the COVID‐19 related incidents in these six months (including preventable cases of hospital transmission and avoided mishaps), their causes, the effect on the functioning of the department and how they have modified our current practice. Data was collected from patients about their difficulties faced routinely at the outpatient department (OPD) or on admission.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data. Categorical variables were compared using the χ 2 test for proportions. All tests were two‐sided with a significance level set at a p value of .05. Differences in proportions were reported as applicable, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The data were analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics software version 24 for Linux (IBM Inc.) and R software (https://www.r-project.org). Data were compiled and analysed during October and November 2020.

2.2. Operational strategies used by the department during COVID‐19

Our hospital is the largest tertiary care academic university centre in the most populous state of India, and it was at the forefront of managing the pandemic. The hospital was sectioned into COVID and non‐COVID zones. All patients seeking elective treatment at the OPD of the hospital were required to take an online appointment from a government portal (https://ors.gov.in/index.html). Patients presenting to the emergency room were initially screened at triage, and then tested and kept at a holding area, and then referred to the respective departments for treatment, or to a dedicated COVID unit depending on their COVID‐19 status.

The dedicated COVID unit of the university was initially started at the main campus, but later relocated to a larger standalone facility about 500 m from the main campus realising the need for additional surge spaces and to keep the infectious facility away from the centre of the hospital. It had isolation facilities, intensive care units, emergency operation theatre services, and separate facilities for paediatric, obstetric, and surgical patients. The facility was manned by teams of healthcare workers that were on round‐the‐clock emergency duties, rotated by two weekly shifts from various departments of the university. The university also maintains a dedicated information portal on its website (http://www.kgmu.org/covid-19.php).

2.2.1. Strategies for healthcare workers

Healthcare workers were instructed to follow the meticulous practices of hand hygiene, wearing masks, following social distancing norms, and avoiding group meals. Educational activities were performed via internet‐based applications. From 24th July 2020, every healthcare worker had to submit daily self‐declaration regarding exposure and COVID‐19 like symptoms.

N95 masks and face shields were used in the OPDs and operating theatres, and three‐ply surgical masks elsewhere. Except for some shortages in personal protective equipment in the initial weeks of the pandemic, PPE was adequately available for rational use during surgeries. Usually, healthcare workers were tested for COVID‐19 in the event of suspected contact with a COVID‐19‐positive patient or in case of symptoms. During September 2020 when the number of cases among healthcare workers in the university was rising, the entire university was screened and tested for the virus.

2.2.2. Strategies for operating the OPD

The underlying philosophy was to decrease crowding in OPD. Initially, we used to see all patients reporting to the surgical oncology OPD without any limit (about 200–250 patients in a day). This could potentially lead to a violation of social distancing norms and forced us to limit our OPD to 50 patients in a day, as per the institutional recommendations. Follow‐up times were extended. All the patients were screened by a validated checklist (Table 1) developed by the department before the consultation. Patients were kept at a distance of a minimum of 2 metres. All doctors and other healthcare workers used appropriate protective gear in the OPD. Teleconsultation facilities were offered.

Table 1.

COVID‐19 standard operating protocol

| Personal protection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Following steps shall be taken by ALL employees in the department | |||

| Hand hygiene | Meticulous practice of hand hygiene including washing with soap and water (for at least 20 seconds using the standard six steps) and use of 70% alcohol‐based hand sanitizers. | ||

| Masks | All employees to wear masks at work. Surgical masks (disposable, 3‐ply) or washable double‐layered cotton cloth masks shall be used. Use N‐95 masks in case of aerosol‐generating procedures. | ||

| Social distancing | Physical distancing, preferably of 2 metres shall be practiced. | ||

| Prophylactic treatment | No prophylactic medical treatment is planned as there is an absence of strong guidelines. | ||

| Self ‐declaration | Exposure and COVID‐19 symptoms (From 24th July 2020) | ||

| Patient management | |||

| Patients will be triaged at all levels of care with a checklist for COVID‐19 combining history and body temperature measurement (thermal scanning/digital thermometer). | |||

| Outpatient department (OPD) | The underlying philosophy shall be to decrease crowding in OPD, decrease admissions and decrease the elective surgical load. To achieve this follow‐up times would be extended, neo‐adjuvant treatment options would be explored if feasible (especially for borderline inoperable patients, locally advanced patients) and surgery would be deferred in patients with stable disease. | ||

| Chemotherapy | Following the initial triage patients will receive chemotherapy. Short courses/therapy times/oral drugs shall be preferred. | ||

| Inpatient department (IPD) | Triage would be reviewed and repeated using the checklist. Patients in Surgical Oncology Ward would be allotted beds with adequate distancing (one to two vacant beds between patients). | ||

| Patients being considered for surgery would be rigorously checked for the absence of COVID‐19 symptomology. | |||

| Mandatory RT‐PCR COVID testing for patients before admission (Started from 15th June, 2020). | |||

| Mandatory testing for attendants accompanying patients from (Started from 4th July, 2020). | |||

| Operation Theatre | Additional diligence in asepsis, inter‐personal protection (especially for anaesthesiologists and the surgical team) would be undertaken at all points of time. | ||

| RT‐PCR COVID‐19 testing before surgery (Started from 20th April, 2020). | |||

| Managing COVID‐19 positive patients with cancer | No surgery or anticancer therapy is contemplated in nonemergency situations. | ||

| Checklist | |||

| 1 | History of (H/O) Fever/Upper respiratory tract infection (URI) | Yes | No |

| 2 | H/O Travel (Domestic/International) | Yes | No |

| 3 | H/O Contact with any foreign returnee | Yes | No |

| 4 | H/O Fever in the immediate family | Yes | No |

| 5 | Temperature Recorded | ||

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

2.2.3. Strategies for preoperative management

This was based on international guidelines, and reinforced by institutional recommendations. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 The primary strategy was to decrease inpatient admissions (inpatient department) and the elective surgical load. To achieve this, neoadjuvant treatment options were explored as appropriate in consultation with other departments by a multidisciplinary team approach (especially for borderline inoperable patients, locally advanced patients etc.) and surgery was deferred in patients with stable disease who could be maintained on chemotherapy, metronomic or otherwise. 9 Preoperative multidisciplinary tumour board meetings were held on web‐based applications.

In the initial days of the pandemic when the number of cases in India was less than 1500 cases overall (23rd March to 19th April 2020), we were screening patients by a checklist only (Table 1), which included history and temperature recording. Patients who gave a response of yes to any question, or had a fever on temperature recording were referred to an in‐hospital fever clinic for evaluation. After the COVID‐19 cases increased beyond 1500 but before established community transmission (20th April to 3rd July 2020), we routinely started to test patients for COVID‐19 as part of preoperative workup. 10 From July 2020, with increasing concerns of community transmission, we also started COVID‐19 testing of one attendant of the patient who would stay with him in the perioperative phase in the wards. In our university, COVID‐19 test is performed either by TaqMan probe‐based real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) method or True Nat assay for the screening (E gene) and confirmatory (Orf1a) targets. 11

2.2.4. Strategies used during surgery

From the beginning of the pandemic, operating surgeons used N‐95 surgical masks and face shields during surgery. Operative theatre staff took standard precautions. During intubation and tracheostomy, full personal protective equipment was worn. Minimal staff was kept in the operation theatre during intubation and surgery.

2.2.5. Strategies in postoperative management

All healthcare workers took full precaution wearing at least three‐ply surgical mask at all times. Combined ward rounds were done with minimum personnel possible. We tried to discharge patients at the earliest. Patients were informed of the availability of teleconsultation in case of any emergency. Routinely, patients were seen on follow‐up after four weeks with a mandatory COVID‐19 RT‐PCR report. The standard operating protocol followed has been briefly described in Table 1.

2.2.6. Strategies for radiation therapy

There is a dedicated radiotherapy department in the university that functions in conjunction with the surgical oncology department. The radiotherapy department kept functioning throughout the pandemic, although patient numbers were decreased as compared to nonpandemic times. The department mandated two‐weekly testing of all cancer patients who were on treatment with radiotherapy, including the testing of one attendant. Modifications were made in treatment delivery with the possible avoidance of more advanced or complex radiotherapy techniques requiring longer times for planning and verification, the use of induction chemotherapy in sites where it was evidence‐based, the use of hypofractionation, and proper administrative handling of all healthcare workers. 2

3. RESULTS

3.1. Metrics related to the functioning of the department

From April to September 2020, a total of 20,822 and 2,840 patients were seen in the outpatient clinic and received inpatient treatment, a decrease of 62% and 58%, respectively, from the same period the previous year (Table 2). The department also recorded an average of nearly 500 teleconsultations per month during the 6 months. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 2,150 patients, compared to the usual 6‐month average of 4,896 patients, reflecting a decrease of nearly 56%.

Table 2.

Impact of the pandemic on various services offered in the department

| Services (half‐yearly), April to September | Number (%) in 2019 | Number (%) in 2020 | Inference | p Value | Difference between proportions (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPD | 20822 | 7973 | 62% Decrease | ||

| IPD | 2840 | 1184 | 58% Decrease | ||

| Chemotherapy | 4896 | 2150 | 56% Decrease | ||

| Teleconsultation | Not recorded | 3476 | – | ||

| Major surgeries | 598 | 410 | 31% Decrease | ||

|

Head and neck Composite resection for oral cancer Laryngectomy Thyroidectomy Parotidectomy Parapharyngeal tumour excision Excision of skin tumours |

310 (52%) | 248 (60%) | 8% Increase | .012 | 1.75% — 14.12% |

|

Gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatic biliary Whipple's procedure Radical cholecystectomy Gastrectomy Colectomy Excision of retroperitoneal tumour |

108 (18%) | 66 (16%) | 2% Decrease | .409 | −2.81% — 6.60% |

|

Genitourinary Nephrectomy Penectomy Staging laparotomy Cytoreductive surgery Radical hysterectomy Vulvectomy |

78 (13%) | 43 (11%) | 2% Decrease | .341 | −2.20% — 5.97% |

|

Thorax and breast BCS, MRM Esophagectomy Mediastinal mass resection Pneumonectomy |

49 (8%) | 28 (7%) | 1% Decrease | .556 | −2.47% — 4.22% |

|

Others Sarcoma Skin tumours |

53 (9%) | 25 (6%) | 3% Decrease | .081 | −0.41% — 6.20% |

|

Minor Surgeries Biopsy Chemo port insertion Suturing Flap delay and division Upper GI endoscopy Lower GI endoscopy Video laryngoscopy Colposcopy |

712 | 389 | 45% Decrease |

Note: Numbers in parentheses indicate proportion with respect to the number of major surgeries.

Abbreviations: IPD, inpatient department; OPD, outpatient department.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

There was an overall decrease in the number of major surgeries performed and surgeries across all disease sites, with the most common sites operated being head and neck, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary. However, there was a significant increase in the proportion of head and neck cancer patients operated upon although the absolute numbers were lower than the previous year (p = .012; absolute difference 8%; 95% CI: 1.75% — 14.12%). On average, about 82 patients were operated by each consultant surgeon in these 6 months against 119 patients on usual days from last year.

The incidence of postoperative morbidities was similar to the previous year overall (p = .593; 95% CI:−2.61%–— 4.87%) and across disease sites (Table 3). Postoperative complications (Clavien‐Dindo) were similar (p = .315; 95% CI: −1.86% — 6.11%). The most common grades of complications were Grades II and III during the current period and Grades I and III in the previous year. Postoperative mortality was recorded in five patients (1%). In the last six months, none of our postoperative patients (n = 410) were found to be COVID‐19 positive during the period of hospital stay. However, two of these patients (0.5%) were found to be COVID‐19 positive later on, but within the postoperative period of 30 days. This can be attributable to our rigorous screening protocol.

Table 3.

Details of postoperative complications

| Number (%) before COVID‐19 | Number (%) | p Value | Difference between proportions (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative morbidity | 53/598 (9) | 43/410 (10) | .593 | −2.61% — 4.87% |

| Head and Neck cancer | 27/310 (8) | 30/248 (12) | .114 | −0.97% — 9.28% |

| Oro‐cutaneous fistula | 15 | 15 | ||

| Surgical site infection | 15 | 10 | ||

| Flap loss | 03 | 03 | ||

| Bleeding | 01 | 02 | ||

| Wound dehiscence | 01 | 02 | ||

| Pharyngo‐cutaneous fistula | 00 | 02 | ||

| Chyle leak | 01 | 01 | ||

| Pneumonia | 00 | 01 | ||

| Ophthalmic nerve paresis | 00 | 01 | ||

| Hypocalcaemia | 00 | 01 | ||

| Gastrointestinal and hepato‐pancreaticobiliary cancer | 12/108 (11) | 07/66 (11) | 1.000 | −9.13% — 10.82% |

| Anastomotic leak | 00 | 02 | ||

| Surgical site infection | 10 | 01 | ||

| Delayed gastric emptying | 00 | 01 | ||

| Ileus | 00 | 01 | ||

| Pancreatic fistula | 02 | 00 | ||

| Bile leak | 01 | 00 | ||

| Wound dehiscence | 02 | 00 | ||

| Genitourinary tract cancer | 06/78 (8) | 02/43 (5) | .536 | −8.73% — 11.91% |

| Surgical site infection | 04 | 02 | ||

| Fistula | 01 | 00 | ||

| Dehiscence | 01 | 00 | ||

| Thorax and breast cancer | 04/49 (8) | 03/28 (11) | .662 | −10.10% — 20.25% |

| Surgical site infection | 03 | 01 | ||

| Air leak | 00 | 01 | ||

| Delirium | 00 | 01 | ||

| Fistula | 01 | 00 | ||

| Flap necrosis | 01 | 00 | ||

| Others | 03/53 (6) | 01/25 (4) | .716 | −14.02% — 12.36% |

| Graft loss | 00 | 01 | ||

| Surgical site infection | 03 | 00 | ||

| Postoperative complications (Clavien‐Dindo grade) | 60/598 (10) | 48/410 (12) | .315 | −1.86% — 6.11% |

| I | 29 (5) | 04 (1) | ||

| II | 01 (1) | 18 (4) | ||

| III | 23 (4) | 20 (5) | ||

| IV | 00 (0) | 01 (1) | ||

| V | 07 (1) | 05 (1) |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.2. Difficulties faced by patients

The most common difficulties encountered by patients attending OPD were lack of transportation (58%), apprehension of COVID‐19 infection (52%), and financial issues (36%), or logistic issues (17%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Difficulties faced by patient and reasons of inability to keep an appointment for surgery

| Difficulties faced by patients who attended OPD, number (%) | Reasons for inability to keep surgical appointment, number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Problems faced by patients | (Total patients, n = 7973) | (Total patients, n = 389) |

| Transportation | 4624 (58) | 154 (40) |

| Apprehension of COVID‐19 infection | 4209 (53) | 204 (52) |

| Acquiring movement pass | 1363 (17) | 36 (9) |

| Arranging finances | 2894 (36) | 191 (49) |

| Arranging meals during travel | 1538 (19) | 0 (0) |

| Unawareness about the functioning of the department | 0 (0) | 184 (47) |

| Lack of social support | 0 (0) | 71 (18) |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Nearly 400 patients who had been kept in the waiting list for surgery in the department did not turn up. Common reasons for the inability to keep an appointment for surgery were apprehension of COVID‐19 infection (52), inability to arrange finances (49%), or unawareness about the functioning of the department (47%) (Table 4).

3.3. COVID‐19 related incidents

During these six months, we encountered two COVID‐19 related incidents in our department (Table 5). The first happened on the 4th of July, 2020, when a patient of gallbladder cancer was admitted for surgery. This patient was wrongly labelled as COVID‐19 RT‐ PCR negative. This human error resulted in the exposure of ten resident doctors, nine healthcare workers, and three patients, leading to the cessation of operative care for a week. The second incident happened on the 19th of August 2020, when a nursing staff in our preoperative ward continued to work and ignored symptoms of mild sore throat. Later on, she was investigated and found to have COVID‐19 infection. This catastrophe resulted in infecting three patients and 21 healthcare workers, including three resident doctors. All the faculty members of the department were exposed as secondary contacts leading to the closure of operative services again for a week (Table 5).

Table 5.

Accidents related to COVID‐19 in the department during this period

| Date | Source of infection | Cause of event | Infected | Impact on department | Lesson learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th July, 2020 |

Patient (Gallbladder cancer) |

Human error (COVID‐19 positive patient wrongly stamped as negative) |

Patient—3 Hospital staff—0 |

All (10) resident doctors primarily exposed All consultants secondarily exposed Department closed operative services for 1 week |

(1) We have started checking RT‐PCR COVID‐19 reports on portal site 12 (2) Checking COVID‐19 RT‐PCR of the patient and one attendant before admitting any patient (3) Divided resident doctors in two teams to prevent all residents to be infected at a time. (One to look after OPD and preoperative ward and second to look after OT and postoperative ward) |

| 19th August, 2020 | Ward sister | Ignoring mild sore throat |

Patient—3 Hospital staff—18 including staff of preoperative, postoperative ward and OT Residents—3 |

All consultants, resident doctors, and staff primarily exposed Department closed operative services for 1 week |

(1) Filling self‐declaration form for hospital staff and doctors Explaining the importance of self‐declaration about wellness (2) If any symptoms or exposure of COVID‐19, immediate quarantine, and joining after negative RT‐PCR |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.4. COVID‐19 related incidents avoided

Taking cues from the previous two COVID‐19 incidents, we were able to prevent at least 15 events between the period of July to September. Fifteen patients who were either planned for surgery (11) or chemotherapy (4), or their relatives were found to be COVID‐19 positive. In three patients who were planned for surgery, the accompanying relatives tested positive for COVID‐19. We were able to identify them because of our policy of admission only after checking a recent COVID‐19 RT‐PCR test report (<1 week) of the patient, and one attendant and again verifying it on the government portal for COVID‐19. 12 Patients that became positive were sent to the dedicated COVID‐19 unit of the university and underwent the required isolation and treatment. For patients whose relatives (contacts) were found to be positive underwent retesting after 7 days.

4. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has resulted in a significant problem of providing care for cancer patients. The difficulty is both at the level of patients who are unable to reach hospitals for appropriate care and also the inability of the hospitals to deliver services in the constrained environment of the pandemic. Hospitals, in general, are overwhelmed with the care of COVID‐19 patients, and there are safety issues for medical and paramedical staff.

Given these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that the clinical services of the department have fallen drastically. OPD attendance, chemotherapy and elective surgery have reduced substantially. We saw only 38% of our usual OPD load. Our total admission and chemotherapy dropped by more than 50%, and major and minor surgical procedures dropped by about 31% and 45%, respectively.

Several tertiary level academic oncology centres from India have reported their experiences of cancer surgery during the pandemic. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 India's largest oncology centre was reported to have a decrease in operated cases by a third. 20 Shrikhande et al. 13 reported outcomes in a large cohort of 494 patients from the same centre albeit performed over a smaller duration of 2 months with a similar incidence of postoperative complications as the present study. In the cohorts reported by Sultania et al. 14 and Pai et al., 17 56 procedures and 184 major procedures were done, respectively. The incidence of postoperative complications was again higher than our present study, and one and three cases of mortality were reported, respectively. 14 , 17 Ramachandra et al. 15 describe the outcomes in 359 operated patients from a large centre in south India, with a similar incidence of postoperative complications as our study and one death. In our study, the incidence of Grades II and III complications in the present scenario, as opposed to more Grades I and II complications in the previous year, maybe due to an attempt by the surgeons to intervene on the complications to facilitate early discharge. Interestingly, in the studies from Tata Memorial Hospital 13 and Ruby Hall Clinic, 19 there were no postoperative deaths.

While these cohorts have characterised demographics, type of surgeries, and outcomes including complications, there is no direct comparison as such to their functioning as compared to the pre‐COVID‐19 phase. Recently, Subbiah et al. 16 from Chennai, India have published their experience with 234 major and 1738 minor procedures performed over 5 months during this period. They report decreases of 63.5%, 61.6%, 64.5%, and 55.4%, respectively, in outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, major, and minor procedures with a proportional decrease across disease sites. In that context, our degree of decrease while similar for outpatient and inpatient visits were lower for major and minor surgical procedures. 16 A prospective matched study of surgical cases from the United States reported a decline across all subspecialities, with the maximum decrease in sarcomas. For them, the decline was significant only after the country had declared a nationwide emergency and not at the onset of the pandemic. 21

The decision regarding which patients to operate during this crisis is hardly easy. Several guidelines or recommendations have come up recommending the selection of patients for surgeries and on preoperative testing. 7 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 In general, we have operated on patients where curative intent surgery was feasible and neoadjuvant treatment was ineffective. Complex and borderline surgical procedures were done after diligent workup, screening and COVID‐19 testing. To minimise complexities associated with surgical procedures and facilitate early postoperative recovery, we utilised locoregional flap more often than microvascular flap reconstruction in head and neck cancers. 31 A recently published questionnaire‐based cross‐sectional study reported better preparedness in Tier‐1 Indian cities, public institutions, and specialist oncology institutes. 32

Since the problem of COVID‐19 seems unlikely to be resolving soon, the effect on cancer patients who could not reach hospitals in time or where surgery was not possible is a problem which cannot be addressed promptly. The consequences of delaying surgery will be detrimental for the patients and will result in the deterioration of their quality of life. A significant proportion of these cancer patients may not be amenable to curative surgery in the future due to disease progression. Hence, a contingency plan needs to be in place. 33 , 34

4.1. Modifications in practice after COVID‐19 related incidents

Bad experiences always stand to make people wiser. The COVID‐19 related mishaps taught us the method of dealing with these problems. To decrease the workload in OPD, we have started teleconsultation in our department. 35 , 36 , 37 Patients can contact any consultant by voice call during the day. If required, the consultant will ask the patient to upload reports on a particular email address generated for this propose, and can also visually examine the patient by video call. This teleconsultation is very good in patients who are on follow up and can avoid long‐distance travel. It also helps in screening individual patients who are candidates for surgical intervention.

After the first incident, we modified our practice, and in addition to RT‐PCR testing of the patient before admission, we also mandated testing of an accompanying attendant. We rely only on a recent RT‐PCR report (<1 week). We have also restricted the number of attendants allowed with patients in the ward. We have started doing routine RT‐PCR testing of all patients who were due either for chemotherapy or some minor procedures. We verify all reports from the government portal site. A limitation of accepting RT‐PCR report for up to 1 week is that the patient can become positive during those seven days. However, patients were admitted in the ward with adequate distancing, counselled about hand hygiene and personal protection, and were prevented to leave the wards post‐admission to reduce this probability.

After the second incident, we started the policy of filling self‐declaration form from all healthcare workers daily to confirm that they are neither exposed nor have any flu‐like symptom. Replacement of injectable drugs or antibiotics with their oral counterparts was done as far as possible further to avoid close contact between staff nurses and patients. All the patients were asked to wear a mask at all times, self‐temperature monitoring, minimal interpatient interaction, and counselled for frequent hand washing and proper sanitisation. The incidents which occurred in our department were avoidable. They were mainly due to human errors. One was due to incorrect manual stamping of the report, and second, was due to delayed self‐reporting of symptoms.

These mishaps which occurred in our department taught us a lesson that the present scenario is somewhat like fighting in a warzone; one may have bombardment from the outside (e.g., the first accident in our department) or from the inside, like a clandestine cell system or sleeper cells (e.g., the second accident in our ward). 38 It is thus essential to safeguard oneself by proper screening, testing, verification of reports and promotion of teleconsultation. It is even more critical to prevent oneself from becoming this sleeper cell by following strict preventive personal and social guidelines (like social distancing, wearing proper protective gear religiously and avoid gatherings) and prompt self‐reporting of exposure or symptoms related to COVID‐19. Although there may be a need to ration personal protective equipment on occasions, it should not leave healthcare workers exposed. 39

5. CONCLUSION

In addition to managing and treating COVID‐19 patients on a priority basis, there is an often unmet need to treat non‐COVID‐19 patients simultaneously so that their morbidity and mortality can be decreased to a reasonable limit. To this end, segregation of hospitals into COVID and non‐COVID zones, ramping up testing of non‐COVID‐19 patients, and arranging appropriate safety equipment for medical personnel is reasonable. We can only serve if we are safe, and there can be a no bigger misfortune than infecting patients during treatment. Thus, rigorous screening and testing of the patients, promoting teleconsultations, following the prevention guidelines, prompt self‐declaration of exposure or symptom by healthcare workers is key to success in this battle. The principles of “lead well, choose well, cut well, stay well” are more applicable now than ever. 40

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

SYNOPSIS

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic makes the treatment of non‐COVID illnesses more challenging. This retrospective cohort study found a decrease across all operations (outpatient, inpatient, surgical procedures, chemotherapy) of a tertiary care surgical oncology facility without compromising clinical outcomes. While it may be a formidable challenge, the treatment of major illnesses like cancer can be accomplished by adequate screening and testing procedures, and following the relevant guidelines even during a pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank all the residents, staff, and patients of the department without whose cooperation this work would not be possible. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Ankita Ray, postdoctoral researcher at UC Louvain, Belgium (formerly of ETH Zürich, Switzerland) for her help in preparation of the figure. Crystal structure of viral proteins used in the figure have been rendered with Chimera (University of California, San Francisco) using Protein Data Bank (PDB) files 6LU7 and 6LZG. (Image for coronavirus: Maria Voigt/RCSB PDB).

Akhtar N, Rajan S, Chakrabarti D, et al. Continuing cancer surgery through the first six months of the COVID‐19 pandemic at an academic university hospital in India: A lower‐middle‐income country experience. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123:1177–1187. 10.1002/jso.26419

Shiv Rajan and Deep Chakrabarti are equal contributors.

Vijay Kumar, Sanjeev Misra, and Arun Chaturvedi are senior authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Relevant datasets for this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507‐513. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chakrabarti D. The Eleventh Hour. Clin Oncol. 2020;32:407‐408. 10.1016/j.clon.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chakrabarti D, Verma M. Low‐dose radiotherapy for SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia. Strahlentherapie Und Onkol. 2020;196:736‐737. 10.1007/s00066-020-01634-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nepogodiev D, Bhangu A, Glasbey JC, et al. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396:27‐38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American College of Surgeons. COVID‐19 : Guidance for Triage of Non‐Emergent Surgical Procedures n.d. https://www.facs.org/COVID-19/clinical-guidance/triage.

- 6. Wang L, Lu X, Zhang J, Wang G, Wang Z. Strategies for perioperative management of general surgery in the post‐COVID‐19 era: experiences and recommendations from frontline surgeons in Wuhan. Br J Surg. 2020;107(10):e437. 10.1002/bjs.11886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nekkanti SS, Nair S, Parmar V, et al. Mandatory preoperative COVID‐19 testing for cancer patients—Is it justified? J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:1288‐1292. 10.1002/jso.26187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ribeiro R, Wainstein AJA, Castro Ribeiro HS, Pinheiro RN, Oliveira AF. Perioperative cancer care in the context of limited resources during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Brazilian Society of Surgical Oncology Recommendations [published online ahead of print September 26, 2020]. Ann Surg Oncol. 1‐9. 10.1245/s10434-020-09098-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rajan S, Kumar V, Akhtar N, Gupta S, Chaturvedi A. Metronomic chemotherapy for scheduling oral cancer surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Indian J Cancer. 2020;57(4):481‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collaborative Covids . Preoperative nasopharyngeal swab testing and postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing elective surgery during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;108(1):88‐96. 10.1093/bjs/znaa051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Indian Council of Medical Research . Revised Guidelines for TrueNat testing for COVID‐19 2020. https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/labs/Revised_Guidelines_TrueNat_Testing_24092020.pdf Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 12.Department of Medical Health & Family Welfare. Surveillance Platform UP Covid‐19 2020. https://upcovid19tracks.in. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 13. Shrikhande SV, Pai PS, Bhandare MS, et al. Outcomes of elective major cancer surgery during COVID 19 at Tata Memorial Centre: implications for Cancer Care Policy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e249‐e252. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sultania M, Muduly DK, Balasubiramaniyan V, et al. Impact of the initial phase of COVID‐19 pandemic on surgical oncology services at a tertiary care center in Eastern India. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122(5):839‐843. 10.1002/jso.26140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramachandra C, Sugoor P, Karjol U, et al. Outcomes of cancer surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic: preparedness to practising continuous cancer care [published online ahead of print October 19, 2020]. Indian J Surg Oncol. 1‐5. 10.1007/s13193-020-01250-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Subbiah S, Hussain SA, Samanth Kumar M. Managing cancer during COVID pandemic—experience of a tertiary cancer care center. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;S0748‐7983(20):30799‐X. 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pai E, Chopra S, Mandloi D, Upadhyay AK, Prem A, Pandey D. Continuing surgical care in cancer patients during the nationwide lockdown in the COVID‐19 pandemic—perioperative outcomes from a tertiary care cancer center in India. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:1031‐1036. 10.1002/jso.26134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deshmukh S, Naik S, Zade B, et al. Impact of the pandemic on cancer care: Lessons learnt from a rural cancer center in the first 3 months. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122(5):831‐838. 10.1002/jso.26144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gautam P, Gandhi V, Naik S, et al. Cancer care in a Western Indian tertiary center during the pandemic: Surgeon's perspective. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:1525‐1533. 10.1002/jso.26217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pramesh CS, Badwe RA. Cancer management in India during Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e61. 10.1056/NEJMc2011595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chang EI, Liu JJ. Flattening the curve in oncologic surgery: impact of Covid‐19 on surgery at tertiary care cancer center. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:602‐607. 10.1002/jso.26056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burki TK. Cancer guidelines during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:629‐630. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30217-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Diaz A, Sarac BA, Schoenbrunner AR, Janis JE, Pawlik TM. Elective surgery in the time of COVID‐19. Am J Surg. 2020;219:900‐902. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Classe J‐M, Dolivet G, Evrard S, et al. Recommandations de la Société française de chirurgie oncologique (SFCO) pour l'organisation de la chirurgie oncologique durant l'épidémie de COVID‐19. Bull Cancer. 2020;107:524‐527. 10.1016/j.bulcan.2020.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, Gupta A, Scott J. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID‐19 outbreak [published online ahead of print April 17, 2020]. Ann Surg. 2020. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yeo D, Yeo C, Kaushal S, Tan G. COVID‐19 and the General Surgical Department—measures to reduce spread of SARS‐COV‐2 among surgeons. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e3‐e4. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Di Marzo F, Sartelli M, Cennamo R, et al. Recommendations for general surgery activities in a pandemic scenario (SARS‐CoV‐2). Br J Surg. 2020;107:1104‐1106. 10.1002/bjs.11652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1097‐1103. 10.1002/bjs.11646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Welsh Surgical Research Initiative (WSRI) Collaborative . Surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic: operating room suggestions from an international Delphi process. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):1450‐1458. 10.1002/bjs.11747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. COVIDSurg Collaborative . Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID‐19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):1440‐1449. 10.1002/bjs.11746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rajan S, Akhtar N, Kumar V, et al. A novel and simple technique of reconstructing the central arch mandibular defects—a solution during the resource‐constrained setting of COVID crisis. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2020;11:313‐317. 10.1007/s13193-020-01233-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Singh HK, Patil V, Chaitanya G, Nair D. Preparedness of the cancer hospitals and changes in oncosurgical practices during COVID‐19 pandemic in India: A cross‐sectional study. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:1276‐1287. 10.1002/jso.26174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turaga KK, Girotra S. Are we harming cancer patients by delaying their cancer surgery during the COVID‐19 pandemic? [published online ahead of print June 2, 2020] Ann Surg. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, et al. Immediate and long‐term impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020;107(10):1250‐1261. 10.1002/bjs.11670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization . Telemedicine: opportunities and Developments in Member States: report on the Second Global Survey on eHealth. Global Observatory for eHealth series—Volume 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pareek P, Vishnoi JR, Kombathula SH, Vyas RK, Misra S. Teleoncology: the youngest pillar of oncology. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1455‐1460. 10.1200/GO.20.00295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Royce TJ, Sanoff HK, Rewari A. Telemedicine for cancer care in the time of COVID‐19. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1698. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hall R You're stepping on my cloak and dagger. Naval Institute Press; 1964.

- 39. Jessop ZM, Dobbs TD, Ali SR, et al. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for surgeons during COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review of availability, usage, and rationing. Br J Surg. 2020;107(10):1262‐1280. 10.1002/bjs.11750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mayol J, Fernández Pérez C. Elective surgery after the pandemic: waves beyond the horizon. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1091‐1093. 10.1002/bjs.11688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Relevant datasets for this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.