Abstract

This article describes the results of a survey of dermatologists regarding the implementation and possible future use of telehealth appointments for common skin complaints.

Teledermatology is an effective method for delivering health care, with strong evidence supporting its use, yet barriers have stalled implementation, including lack of reimbursement, liability concerns, and licensing restrictions.1,2 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic crisis led to rapid adoption of telemedicine to continue care while minimizing in-person contact.3

Historically, most teledermatology studies have focused on store-and-forward models, whereas during the COVID-19 pandemic, regulatory changes from the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services prompted an increase in live-interactive video visits. These changes granted parity in reimbursements between video and in-person visits, removing eligibility and geographic restrictions.4,5 We sought to assess dermatologists’ perceptions of and experiences with teledermatology in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and these new changes.

Methods

In May and June 2020, an American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Teledermatology Task Force subgroup surveyed AAD members regarding the effects of COVID-19 on teledermatology. Topics included modes used; situational appropriateness; and opinions regarding reimbursement, perceived need, barriers, and anticipated future use. Questions were tested for face validity and readability and approved by the Task Force and AAD representatives (see Supplement for detailed methods). The AAD administered the survey via email, collected and maintained data, and provided deidentified data for analysis. Participant representativeness based on age, sex, practice type, practice location, employment type, and prior teledermatology use was evaluated. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Results

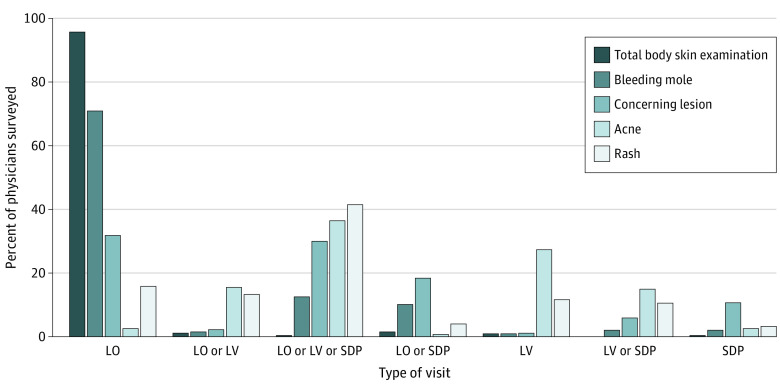

A total of 5000 participants from the group of 12 070 practicing US dermatologist members of the AAD were selected for the survey, from which there were 4356 responses, excluding nonfunctioning email addresses. A total of 591 dermatologists completed surveys (13.6% response rate). Mean participant age was 49.3 years (95% CI, 48.4-50.3), with most practicing in dermatology-based group (257 of 571, 45.0%) and solo (141 of 571, 24.7%) practice. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 82 of 582 (14.1%) respondent dermatologists had used teledermatology, compared with 572 of 591 (96.9%) during the COVID-19 pandemic; 323 of 557 (58.0%) expected to continue teledermatology use after the COVID-19 pandemic. Live-interactive was the most common modality, for 538 of 572 respondents (94.1%), and 406 of 564 (72.0%) of respondents perceived the hybrid model combining video and stored photographs as having the greatest accuracy. The most common barriers to implementation included technology/connectivity issues during visits (223 of 570, 39.1%), low reimbursement (398 of 570, 69.8%), concerns regarding malpractice/liability (154 of 570, 27.0%), and government regulations (132 of 570 23.2%). The majority of respondents (357 of 419, 85.2%) felt reimbursement for store-and-forward teledermatology was too low. When asked about the appropriateness of teledermatology for 5 common complaints (total body skin examination, concerning lesion, acne, rash, bleeding mole), 512 of 535 (95.7%) felt that skin checks required in-person examination, compared with 14 of 549 (2.6%) for acne (Figure).

Figure. Dermatologist Recommendation of Visit Type According to Skin Complaint.

Dermatologists were asked what visit type(s) were appropriate for a total body skin examination (darkest blue), a bleeding mole (slate blue), a concerning lesion (medium blue), acne (paler blue), or a rash (lightest blue). For a total body skin examination, 95.7% of dermatologists felt only a live, in-office visit (LO) was appropriate. Conversely, for acne, only 2.6% of dermatologists felt that an in-office visit was the only appropriate selection, with the remainder noting either teledermatology or in-office visit (52.5%) or teledermatology alone (44.8%). Abbreviations: LO, live office visit; LV, live video visit; SDP, stored digital photography.

Older dermatologists were less likely to report reimbursement concerns (odds ratio [OR] = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99; P = .02) or malpractice/liability concerns (OR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99; P = .02). Male respondents were more likely to report reimbursement being too low (OR = 1.95; 95% CI, 1.03-3.70; P = .04). Rural dermatologists were more likely to use non-HIPAA compliant platforms (OR = 2.41; 95% CI, 1.04-5.56; P = .04), cite government regulations as barriers to future use (OR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.11-4.89; P = .03), and report “no need” for teledermatology (OR = 6.77; 95% CI, 2.08-22.0; P = .002).

Answers to Likert-based questions are shown in the Table. Notably, experience with teledermatology prior to COVID-19 was associated with increased satisfaction with quality of care (OR = 2.05; 95% CI, 1.24-3.39; P = .01) and increased plans to continue usage after COVID-19 (OR = 3.37; 95% CI, 2.08-5.45; P < .001).

Table. Frequency and Distributions of Likert-Scale Questions Regarding Teledermatology.

| Question | Completely disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Completely agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Proportion, % (95% CI) | Count | Proportion, % (95% CI) | Count | Proportion, % (95% CI) | Count | Proportion, % (95% CI) | Count | Proportion, % (95% CI) | |

| I am comfortable using video conferencing/video chat outside of work (missing = 38) | 15 | 2.71 (1.66-4.40) | 21 | 3.80 (2.51-5.70) | 37 | 6.69 (4.92-9.04) | 121 | 21.9 (18.7-25.4) | 359 | 64.9 (60.9-68.7) |

| Teledermatology enhanced patient’s access to dermatology services during the COVID-19 pandemic (missing = 37) | 15 | 2.71 (1.66-4.39) | 10 | 1.81 (1.00-3.28) | 36 | 6.50 (4.76-8.82) | 114 | 20.6 (17.5-24.1) | 379 | 68.4 (64.5-72.1) |

| I plan on continuing to use teledermatology in my practice after the COVID-19 pandemic (missing = 34) | 50 | 8.98 (6.91-11.6) | 72 | 12.9 (10.4-15.9) | 112 | 20.1 (17.0-23.6) | 134 | 24.1 (20.8-27.7) | 189 | 33.9 (30.2-37.9) |

| Overall, I was satisfied with the quality of care that I provided my patients using teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic (missing = 37) | 30 | 5.42 (3.84-7.58) | 58 | 10.5 (8.22-13.2) | 124 | 22.4 (19.2-26.0) | 202 | 36.5 (32.6-40.5) | 140 | 25.3 (21.9-29.0) |

| I anticipate that teledermatology will remain a form of consultation for patients after the COVID-19 pandemic (missing = 38) | 24 | 4.34 (2.95-6.34) | 44 | 7.96 (6.01-10.5) | 98 | 17.7 (14.8-21.1) | 177 | 32.0 (28.3-35.9) | 210 | 38.0 (34.1-42.0) |

| My patients had reliable technology (ie, smart phone, computer, video camera) to participate in teledermatology visits during the COVID-19 pandemic (missing = 39) | 31 | 5.62 (4.01-7.82) | 77 | 13.9 (11.4-17.0) | 169 | 30.6 (27.0-34.5) | 177 | 32.1 (28.4-36.0) | 98 | 17.8 (14.8-21.1) |

| Teledermatology should be part of dermatology residency training (missing = 37) | 33 | 5.96 (4.30-8.20) | 45 | 8.12 (6.16-10.6) | 118 | 21.3 (18.2-24.8) | 138 | 24.9 (21.6-28.6) | 220 | 39.7 (35.8-43.8) |

| The improved reimbursement for live video during the COVID-19 pandemic played a role in my decision to practice teledermatology (missing = 42) | 48 | 8.74 (6.69-11.3) | 40 | 7.29 (5.42-9.72) | 56 | 10.2 (7.98-13.0) | 117 | 21.3 (18.2-24.9) | 288 | 52.5 (48.4-56.5) |

| Assuming reimbursement for video visits remains equal to that of in-person visits, I foresee teledermatology becoming an ongoing component of my practice (missing = 39) | 34 | 6.16 (4.47-8.44) | 45 | 8.15 (6.18-10.7) | 82 | 14.9 (12.2-18.0) | 114 | 20.7 (17.5-24.2) | 277 | 50.2 (46.1-54.3) |

| I have access to satisfactory platforms for delivering teledermatology (missing = 37) | 31 | 5.60 (3.99-7.79) | 47 | 8.48 (6.47-11.0) | 110 | 19.9 (16.8-23.3) | 166 | 30.0 (26.4-33.8) | 200 | 36.1 (32.3-40.1) |

Discussion

In our survey, 387 of 554 (70%) dermatologists believed teledermatology will continue after COVID-19, while 323 of 557 (58%) intended to continue use. Thus, dermatologists perceive the importance of telemedicine, but feel personal concern regarding limitations, highlighting the need for supportive reimbursement, regulations, and technological innovation (connectivity and functionality were common concerns). Additionally, our data suggest that refinement of workflow by patient and visit-type selection (follow-up, acne, etc) will likely improve how teledermatology is perceived by dermatologists. Our study was limited by response rate (13.6%), which, while modest, was expected in this setting and provided sufficient numbers for the performed analyses. There was also relative overrepresentation of female dermatologists, as compared with the overall population and sample populations.

Our data capture dermatologists’ current perceptions regarding teledermatology and can inform future policy and advocacy. The future of telemedicine regulation, reimbursement, educational implementation, and technological implementation will greatly affect commonplace use of teledermatology post-COVID-19, and we hope these data can support these efforts.

eMethods.

References

- 1.Coates SJ, Kvedar J, Granstein RD. Teledermatology: from historical perspective to emerging techniques of the modern era: part I: history, rationale, and current practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):563-574. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey JB, Valenta S, Simpson K, Lyles M, McElligott J. Utilization of outpatient telehealth services in parity and nonparity states 2010-2015. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(2):132-136. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee I, Kovarik C, Tejasvi T, Pizarro M, Lipoff JB. Telehealth: helping your patients and practice survive and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis with rapid quality implementation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1213-1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed July 18, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

- 5.Perkins S, Cohen JM, Nelson CA, Bunick CG. Teledermatology in the era of COVID-19: experience of an academic department of dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(1):e43-e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.