Abstract

Aim

To explore the experiences of the first nurses assigned to work in COVID‐19 units with the onset of the outbreak in Turkey.

Background

Even though the risks faced by nurses while performing a dangerous task during the epidemic are similar, their experiences may differ.

Method

This qualitative study was carried out with 17 nurses. The interviews were carried out individually and online. The data were analysed using Colaizzi's phenomenological method.

Results

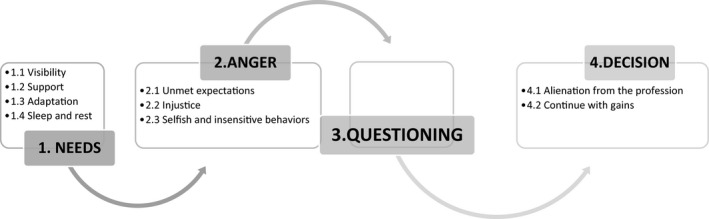

From the analyses of the data, four key themes have emerged as follows: ‘needs’, ‘anger’, ‘questioning’ and ‘decision’. Needs include visibility, support, adaptation and sleep/rest. Nurses were angry because of their unmet expectations, feelings of injustice, and selfish and insensitive behaviours they faced. They questioned their profession and decided to either alienate from the profession or continue with the gains they had made.

Conclusion

This study found that nurses perceived an imbalance between their efforts and their achievements.

Implications for Nursing Management

This study provides evidence for nursing managers to anticipate problems that may arise both during and after the outbreak. Nurses should be made to feel that they are valued members of the health care institution, and effective strategies should be implemented to improve their perceptions of organisational justice.

Keywords: COVID‐19, nurse experience, organisational justice, pandemic, qualitative study

1. BACKGROUND

The coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) continues to seriously threaten public health and the health care system (WHO, 2020). Due to its high transmission rate, the virus has caused many deaths with millions of confirmed cases worldwide, and there was no approved drug for treatment until the time the study was conducted (Li et al., 2020; WHO, 2020). Health care professionals who constitute an extremely important source of workforce resource in the control of the epidemic and the care of patients (Liu et al., 2020) face several challenges from being infected to dying, from overloading to psychological risks (Maben & Bridges, 2020).

Nurses constitute the most front‐line health care workers and are in the closest contact with patients (Liu et al., 2020). Reviewing 59 studies on outbreaks including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), influenza (H1N1, H7N9), Ebola and COVID‐19, Kisely et al. (2020) found that in the clinical groups, nurses are generally at higher risk than doctors. As regular stressors become acute and exacerbated in such crises, it is important to identify the needs and concerns of nurses (Peiro et al., 2020). In quantitative studies (Lai et al., 2020) and reviews (Preti et al., 2020) in the literature on this subject, it has been shown that sleeping and mood disorders involving depression, post‐traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety and distress were high among nurses. In the qualitative studies, it has been demonstrated that Chinese nurses need survival, relationship, growth and development (Yin & Zeng, 2020), but they experienced work pressure, difficulties and different psychological stages (He et al., 2020). In one of the studies conducted with Iranian nurses, it was reported that the main experience included care erosion, the needs of nurses and the development of the profession (Galehdar et al., 2020). As can be seen, qualitative studies provide a broad perspective on the experiences of nurses. However, studies have usually been generally conducted with Chinese and Iranian nurses.

The first case in Turkey was reported by the Ministry of Health on 11 March 2020 (Turkish Ministry of Health, 2020). It was underlined that individual measures should be taken first by the organisation of health services in the management of pandemics such as COVID‐19, and social measures were implemented by expanding their scope over time. According to the density of cases in the regions, emergency services, inpatient services and intensive care units were equipped in hospitals for COVID‐19 patients, or some of the hospitals were designated as pandemic hospitals. Filiation works initiated, informative brochures, posters, guidelines and treatment algorithms relating to COVID‐19 were published (Turkish Ministry of Health, 2020).

Finding themselves abruptly in a chaotic environment, nurses began to work in their new units with sudden changes. The Turkish Nurses Association (TNA) explained the problems nurses experienced during this process and emphasized that nurses had to work in these units without having adequate time and training opportunities. TNA stated that nurses experienced problems such as access to personal protective equipment, fear of getting sick and infecting their relatives and society, lack of personnel and intense and difficult working conditions (Şenol Çelik et al., 2020). Corley et al. (2010) reported that these problems were also experienced by Australian nurses during the H1N1 influenza epidemic. Exposure to social stigma was another problem frequently reported during MERS (Choi & Kim, 2018; Kim, 2017; Park et al., 2018), SARS (Maunder, 2004) and the COVID‐19 outbreaks (Xiang et al., 2020). In addition to these issues, TNA stated that the problems faced by nurses in Turkey were related to fulfilment of basic needs, pricing and their professional and personal rights (Şenol Çelik et al., 2020). However, it is necessary to reveal the experiences of nurses caring for coronavirus suspected or infected individuals through scientific studies. Determining the experiences of nurses with the COVID‐19 pandemic and how they were affected by this challenging process will be a guide for them to develop solutions.

It is the duty of nursing managers to manage nursing manpower in health care organisations, to provide appropriate recruitment, employment and relocation. This task can be more challenging in crisis such as epidemics. As a matter of fact, one study revealed that the management of the COVID‐19 crisis was perceived differently from other crises by nursing managers (Poortaghi et al., 2021). Grasping the experiences of nurses from the moment that they are selected to work with suspected coronavirus or diagnosed patients can provide nursing managers useful information to manage nursing staff more appropriately in this period of epidemic and in possible new outbreaks in the future. In this context, the research aimed to explore the experiences of the nurses who were first assigned to work in COVID‐19 units in Turkey from the very beginning of the process.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

A qualitative study of phenomenological research design has been adopted to explore the experiences of front‐line nurses caring for coronavirus‐infected patients. This design was chosen because it offers a high degree of freedom in defining a new phenomenon (event or experience) from the perspective of the participants, providing rich data and detailing their experiences (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2016). In particular with the establishment of various COVID‐19 units in the hospitals where they work, a descriptive phenomenological approach was followed to understand the lived experiences of the nurses who were first selected to work there. This approach is concerned with revealing the essence of the researched phenomenon and capturing the experience ‘precisely as it presents itself, neither adding nor subtracting from it’ (Morrow et al., 2015; Willing, 2013). Although the phenomenon has been tried to be seen from the participant's perspective, we should state that the researcher is a tool in data collection and analysis, lives in the same sociocultural environment with the participants and has nursing experience; therefore the epistemological paradigm guiding this study is a constructivism (Merriam, 2018).

Participants in this study were selected via the purposeful and snowball sampling method. The study involved registered nurses who were first assigned to work in COVID‐19 units and who were in their positions for more than a month and agreed to voluntarily participate in the study. The criteria for inclusion in the study were a registered nurse who was the first to be assigned to work in COVID‐19 units and held this position for more than a month and agreed to voluntarily participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were nurses who were not working in the COVID‐19 unit during the research period and who were COVID‐19‐positive. Moreover, among nurses working in the hospitals and COVID‐19 units (emergency department, inpatient service, intensive care unit, filiation) from the different regions (Marmara, Aegean, Central Anatolia and South‐eastern Anatolia Regions) of Turkey, 21 nurses were invited to the interview. Among them, one did not have time and three did not choose online meetings, so they were unable to attend the study. The sample size (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2016) was determined by the data saturation, and 17 participants were interviewed in total. The demographic and professional features of the nurses participating in the study are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participants’ characteristics

| Participant number | Age, years | Gender | Marital status | Working experience | Original department | Unit assigned to | Days worked on COVID−19 unit before the interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 25 | Female | Single | 2.5 years | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 60 days |

| P2 | 24 | Male | Single | 4.5 months | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 84 days |

| P3 | 27 | Male | Single | 1.5 years | Surgery | COVID−19 Service | 47 days |

| P4 | 26 | Female | Single | 2 years | Surgery | COVID−19 Service | 45 days |

| P5 | 31 | Female | Single | 9 years | Hematology | COVID−19 Service | 41 days |

| P6 | 25 | Female | Married | 5 years | Gynecological Oncology | COVID−19 Service | 75 days |

| P7 | 43 | Female | Married | 23 years | Vaccination Unit | COVID−19 Emergency | 90 days |

| P8 | 39 | Female | Single | 18 years | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 90 days |

| P9 | 24 | Female | Single | 11 months | Neurology ICU | COVID−19 ICU | 120 days |

| P10 | 31 | Female | Married | 13 years | Psychiatry | COVID−19 Service | 114 days |

| P11 | 31 | Female | Married | 13 years | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 114 days |

| P12 | 23 | Female | Single | 5 years | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 120 days |

| P13 | 27 | Female | Single | 5 years | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 120 days |

| P14 | 39 | Female | Married | 20 years | Infectious Diseases | COVID−19 Service | 150 days |

| P15 | 23 | Female | Single | 9 months | Cardiovascular Surgery ICU | COVID−19 Service + ICU | 150 days |

| P16 | 24 | Female | Single | 5 months | Emergency Service | COVID−19 Emergency | 60 days |

| P17 | 23 | Female | Single | 9 months | Obstetrics | Filiation | 150 days |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

2.2. Data collection and instruments

The data were collected by the researchers between 27 May and 25 August 2020. Semi‐structured interviews were carried out individually via Skype. The aim and process of the study were explained by contacting each potential participant over the phone. An appointment was made with the participant who accepted to participate in the study. Seven potential participants were already known to one of the researchers (NY or AA). The researcher (MB), who had no connection with these participants, made an appointment with the participants and conducted the interview. Thus, the participants were made to feel comfortable while sharing their experiences, and the rest of other participants were reached with a snowball sampling method. Researchers MB and AA together interviewed two of the recruited participants, thus ensuring consistency in the flow of interviews. The interviews were conducted by experienced researchers who were trained in qualitative research interview techniques. Collaboration with the participants was established, and techniques such as unconditional acceptance, active listening and explanation were used to improve the authenticity of the data. All interviews were conducted separately in a single‐person hotel room (one participant), in a guest house (one participant) and in the home (interviewer and 15 participants) in an independent, quiet and safe environment.

At the beginning of the interview, information was obtained about the age, sex/gender, marital status, level of education, nursing experience, the region and the type of institution they were currently working in, their main departments, the COVID‐19 unit they were assigned to and the number of days they worked in that unit. Then, with the open‐ended question ‘Could you please tell us about your working process with patients who are suspected or diagnosed with coronavirus?’ they were asked to describe their experience from the beginning of the process. To obtain detailed accounts, questions such as ‘How were the first nurses to work in the COVID‐19 units selected?’, ‘How was your assignment communicated to you’ and ‘What was your first reaction when you learned this?’ were asked. In the following, the questions ‘How do you feel about the next process and now’ and ‘How do you think your experiences affect your personal and professional life?’ were also asked.

There was only one interview per day between data collection dates. Interviews took about 45–60 min. All interviews were recorded with the permission of the participant, and online recordings were transcribed within 24 hr by the interviewer on the evening of the interview. Since the interview recordings included images and sounds, the non‐verbal indications of the participant could be more clearly noticed.

2.3. Data analysis

In the analysis of the qualitative data obtained from the interviews, the 7‐step analysis method developed by Colaizzi (1978) for the phenomenological studies was used (Morrow et al., 2015). In this context, the interview texts were first read by three researchers independently and repeatedly. Thus, the data were made familiar and it was tried to be understood what was being explained. The important statements in the interview texts were selected, and restated and expressed in general terms. Then, the implicit data within the statements were identified and analysed. The researchers formulated the meanings by discussing them until they reached a consensus and validated them. In the following, they identified and organised the themes into clusters and categories. The themes and subthemes of the research were developed with clear statement expression. The findings of the research were presented to the participants, and the accuracy of the themes and content was strengthened. In addition, the comments of the participants were referred to so that the reader could verify the interpretation and analysis of the data.

2.4. Ethical issues

This research was approved by the Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal University Human Research Ethics Committee (Institution No. 2020/05). Informed consent was obtained from the participants before starting the interview. Recordings and transcripts were stored on a password‐protected device. Each step of the research was written using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines developed for use in reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., 2007).

3. RESULTS

In this study, a total of 17 nurses, two male and 15 females, were interviewed. Their average age is 28.52 (23–43) years. Six of the participants work in different hospitals affiliated to the Ministry of Health in the Marmara region, five in the Central Anatolia, three in the Aegean region and three in the South‐eastern Anatolia region. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Four main themes and nine subthemes were attained with the interviews (Figure 1).

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of themes and subthemes

Theme 1: Needs

As a result of the interviews with the nurses, four subthemes were attained under the main theme of needs.

1.1. Visibility: All participants stated that despite their work at the forefront, they were not visible and their needs for respect and value were not met.

‘I am there for you… Not only the doctor who is there and if you are going to thank, if you really want to thank, do not present it just one person, see me too… We want to be more visible…’. P4

‘I am not the other medical staff. I am a nurse. But, not the other medical staff… If I had so many difficulties after all, why should I have so much hardship if it is not respected?’ P16

1.2. Support: Participants emphasized the importance of the need for support from institution managers to the public and from equipment to emotional support.

‘It is important to be supported, for instance. In this process, the thing was good, the support from the public to us, this was very nice…’. P2

Most of the participants stated that they experienced a lack of equipment in the first weeks of the pandemic, but later, this problem was largely solved, although it varied from institution to institution.

‘It's like entering the middle of a war without a sword and a shield, how am I going to survive it? I felt like. I was shocked.’ P3

Most of the participants often stated that they did not get enough support in the field and that they were left alone and helpless.

‘You see that even your friend does not stand really by you…’. P8

‘We needed executives who could understand and manage us, we felt very lonely. Everyone was locked in their room, I didn't get much support, frankly, we felt like we were left to our destiny’. P13

1.3. Adaptation: Assignments outside their professional field of work, the regulation of their working styles and the sudden change of their workplaces according to the need caused nurses to adapt themselves or to create a new order in an environment they did not know before. It was found that late or unreported information complicates professional compliance for the participants.

‘… You adapt to one place, then you have to forget about it completely and adapt to the work of the other place…’. P15

‘No information was given by the administration, I became anxious, not knowing how to do this, lack of knowledge and inexperience made me nervous’. P11

1.4. Sleep and rest: Some of the participants stated that they were very tired, and their sleeping patterns were disturbed due to busy working conditions and long shifts. In addition, indicating they could not get leave due to the insufficient number of nurses, the participants stated that they needed a break and leave, even for a short time.

‘There has been a tremendous disruption in my sleeping patterns. This is the biggest impact on me since March’. P5

Theme 2: Anger

It was revealed that the participants felt intense fear and anxiety in the first weeks of the pandemic, but this soon turned into anger, and its severity was high. During the interview, it was observed that while expressing their experiences, their voices rose and trembled, and from time to time, they cried. It was observed that among the most frequently stated sources of anger were their needs not being met, feeling of injustice and thoughts that people other than themselves were being selfish and insensitive.

2.1. Unmet expectations: Participants expressed their discomfort due to the treatment they faced despite working at the risk of their lives of loved ones during the outbreak; feeling worthless, lonely and unsupported; and having inadequate information, lack of transparency, distribution of workload and inequality.

‘I would expect the profession to be paid the importance it should be because we save lives, we make people survive and letting people hold on life…’. P3

‘I would expect our managers to spend time with us in the field. Even if they do not help, let them support us, motivate us. But they didn't’. P10

2.2. Injustice: Almost all of the participants expressed that they were angry with the sense of unfair treatment in the regulations related to the determination of which nurses to be assigned to COVID‐19 clinics and the way the decision was communicated, the performance system and the additional payment during the pandemic period.

‘It was bad because I knew that many of my friends like me were given in clinics in such an unfair way, so it was a bad start…’ P4

‘I think the financial gains could have been better, so I hope that our voices will be heard in this process and the Ministry of Health will make improvements in this regard. At least this will eliminate the injustice, maybe…’. P1

2.3. Selfish and insensitive behaviours: It was understood that most of the participants thought they were abused by selfish, insensitive and partially stigmatizing behaviours of the society and by selfish behaviours of their colleagues, doctors and managers, although they were self‐sacrificing, and that they felt anger.

‘I had a hard time with these teams, whose members were selfish and who thought “let someone else take care of the patient rather than me”’. P2

‘Patients cannot enter the market without wearing a mask, but they can enter the emergency room very easily without a mask…. There is an incredible logic that If I am COVID, you should have it as well’. P16

Theme 3: Questioning.

It was observed that the experiences in this process prompted all participants to question their profession or relationships.

‘…I look at it from an economic perspective and then from an emotional perspective, I run into a contradiction. I position myself somewhere, but I cannot do the same for this profession, or I position this profession somewhere, but I cannot do the same for myself. Frankly, thoughts began to come to my mind as to whether I would be happy in the future, would this satisfy me in the future…’. P3

Theme 4: Decision

As a result of the questioning, it was understood that some of the participants decided that they no longer wanted to continue in this profession, and some of them considered that they developed personally and professionally.

4.1. Alienation from the profession: Some of the nurses indicated that during this period, they became alienated from their profession, that they wanted to retire as soon as possible or that they would leave when possible.

‘I became very alienated from the nursing profession. I mean, I am discouraged by how the profession is regarded… I’ve decided to quit the profession’. P10

4.2. Continue with the gains: Some of the participants stated that they were proud of being a nurse, they realized the importance of their profession and their achievements, the peace they felt after helping the patient could not be compared with financial gains and they felt more satisfaction. Some also noticed that their empathy skills improved and that they were able to understand patients much better in this process and learn to be patient and approach them with compassion. Some stated that they saw their inner strength during the pandemic process and became much more mature.

‘Data on the number of patients recovering every day is released, I really thought that it was my contribution to this picture in the number of patients recovered, that this was one part of my jobs, so I felt like a part of a great success’. P5

‘I really think I have grown up… There is a power within us, maybe our faith in the profession, but there is a power within us, and that power comes out at such times. You feel like you are growing up, you feel that you can…’. P4

4. DISCUSSION

This study focused on the experiences of nurses who were first assigned to conduct their professions among the suspected individuals or diagnosed patients with coronavirus following the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Turkey from the very beginning of the process. Revealing both their primary needs and sources of anger, this study showed that nurses had a perception that they were not treated as they deserved, despite the risks they faced, the responsibilities they took on and their efforts. It was revealed that their experiences in the pandemic process led them to question nursing and brought them to a crossroads.

In other qualitative studies conducted with nurses caring for patients with COVID‐19, their health, safety, information, humanistic concern, interpersonal and family needs (Yin & Zeng, 2020), and the need for comprehensive, financial and moral support from the authorities (Galehdar et al., 2020) were reported. In this study, the need for support and information emerged, and it was determined that nurses' need to be visible, be respected and be valued stands out. Studies conducted before the pandemic show that nursing is perceived by society (Kaynar Şimşek & Ecevit Alpar, 2019), patients and physicians as an auxiliary profession that fulfils the wishes of doctors (Yılmaz et al., 2019), and that nurses have a negative perception on their profession. In Turkish films, it has been determined that nurses are sometimes like saviours but often cannot make their own decisions professionally and cannot use their professional autonomy, and their independent roles are ignored and are reflected on the screen with a sexist perspective (Gören & Şahi̇noğlu, 2018). Although the discomfort of nurses for being categorized as ‘other health care workers’ and their efforts to make their voices heard in our country are not new, this fact continues to increase significantly in this period. In other words, the problems that were already present regarding the education, management and personal rights of our profession have deepened with the epidemic. That the number of nurses working is almost 200,000, and that per 1,000 is 2 compared with the country's population; problems related to working conditions and environment (Senol Çelik et al., 2020) may become even more challenging in this period. Unknown and unforeseen facts about the pandemic process both made the organisation of health services difficult and required sudden decision that would strain the adaptation capacity of nurses. Other factors are similar to those reported in the literature (Kisely et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020), and all significantly increased nurses' psychological burden and their physical burden.

In parallel with the similar studies conducted in different countries (Karimi et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020), it was determined in our study that nurses experienced intense fear and anxiety at first, but these emotions sooner were replaced by anger. In addition to their verbal expressions, the severity of their anger was clearly observed from their tone of voice and facial expressions. Maunder (2004) also reported that during the SARS epidemic, the nurses were outraged by their reluctant selection and not being allowed to refuse their appointments. The ICN stated that nurses are angry and that the main reason for their anger was lack of support and unpreparedness (ICN, 2020). For these reasons, in our study, nurses mostly emphasized unfair treatment as the source of their anger. The nurses thought that they were subjected to injustice by comparing what they achieved through their efforts, both with their expectations and with other employees. In a study conducted with nurses involved in the COVID‐19 rescue mission, feelings of unfairness were reported as one of the identified themes (Sheng et al., 2020). Kim (2018) revealed that in the MERS epidemic, nurses were disappointed that they were not rewarded for their efforts in such a risky situation. Organisational justice must be provided for the welfare of employees in institutions. It can become even more important in times of health crises, such as epidemics. Conducting our study during the pandemic period and with the first assigned nurses may have made the feelings of unfairness more pronounced.

Organisational justice is considered to have three components: distributive, procedural and interactional justice (Colquitt, 2001). In our study, results were obtained, including all three dimensions of organisational justice. When the COVID‐19 epidemic started in our country, the nurses who started to work with individuals with suspected coronavirus or patients diagnosed with it first evaluated whether the distribution of tasks, the distribution of protective equipment and then the distribution of additional payments were fair. This assessment corresponds to the distributive justice component. In previous quantitative studies conducted with nurses in our country, this dimension of organisational justice was reported to be lower than other components (Seyrek & Ekici, 2017). In terms of procedural justice regarding the issue of how the distribution was carried out, nurses questioned how decisions were made—such as which hospital would be a pandemic hospital and which nurses would work in COVID‐19 units—and stated that the managers of the institutions they work with should be transparent. They also clearly stated that they were uncomfortable with the way the decisions were communicated. This disturbance also shows that in terms of the interactional justice component, they think that the relationship between the decision‐makers and the executive of the procedures and the employee is unfair. It is one of the stated experiences that they suddenly learned that they were assigned to a different service while getting used to a new service just through a message sent to the phone. This situation also led to increased uncertainty, vigilance, feeling anxious and uneasy, and inability to rest. In the months when COVID‐19 cases were intense, the removal of their annual leave rights, even the suspension of their rights such as leaving the profession and resignation, may cause an increase in anger of physically exhausted nurses due to their restricted rights. As a matter of fact, when the findings of this study were presented to the participants, some of them stated that they experienced these feelings much more intensely in the last months.

Numerous studies on organisational justice have shown that the perception of justice has many emotional, attitudinal and behavioural consequences (Aboul‐Ela, 2014). In other studies, it was found that organisational justice in nurses was associated with work engagement, turnover intention (Cao et al., 2020), workplace deviance (Hashish, 2019), threatening and negative behaviours (Seyrek & Ekici, 2017). These results seem similar to our study, the nurses questioned their profession and stated that they no longer wanted to continue their nursing duties and would leave when they had the opportunity. Taking these into consideration, it suggests that nurses' sense of injustice may have serious consequences today and after the epidemic is brought under control. During the 2003 SARS epidemic, it was reported that their willingness to work decreased and they were considering resigning (Bai et al., 2004). Crises are turning points. They can create opportunities for development and growth, and challenges and problems. Similar to the results of the various qualitative studies conducted in this process (Galehdar et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Sheng et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020), some of the nurses have also stated that they learned new things from their experiences and this profession. They were proud of doing this and felt stronger. Nurses are undoubtedly the primary professional group that shoulders the heavy burden of this pandemic. Pointing out the key role of nurses, THD delivered the report on the solution of the problems of our country's nurses to the Ministry of Health and published the COVID‐19 nurse training guide, bulletin and video recordings, which include care algorithms that enable nurses to access the most up‐to‐date and evidence‐based information (Şenol et al., 2020). Nurses' voices and perspectives should be integrated into policymaking process to minimize the injustices many nurses have faced to date. Authorities have important roles in facilitating their struggle, making them feel that their efforts are seen, improving the perception of justice and ensuring their participation in decision‐making processes.

5. LIMITATIONS

Participants were investigated from four of Turkey's seven geographical regions. The sample size of this research is limited due to the characteristics of qualitative research. Under the COVID‐19 conditions, interviews had to conduct online, so there have been potential participants who refused to participate in the study. It should be noted here that although the participants were informed about confidentiality, they repeatedly asked whether their names and institutional information would appear in the study. It was observed that they were afraid of getting reactions from their institutions. For these reasons, there are limitations in obtaining additional information and generalizing the research results.

6. CONCLUSION

Nurses are undoubtedly the primary professional group that shoulders the heavy burden of this pandemic, but it was concluded that they thought that they were not appreciated, either materially or morally in return for their sacrifices. The results of this study show that nurses working at the forefront of the pandemic are not only faced with the harsh working conditions, high risk of infection and anxiety brought about by the COVID‐19 pandemic, but also at the same time, it has shown that unmet needs and expectations, organisational injustice, and selfish and insensitive behaviours of their working and social circles create challenges. It is thought that this study can be a reference for the areas that need improvement regarding hospital and nursing management. A healthy and safe working environment, instrumental and informative support, and ensuring organisational justice, strengthening the relationship between managers and nurses and more cooperation are also important. In such crises, nursing managers, having a strong presence in their field, being a good role model for the staff and acting as a leader and administrator, can generate a better impact.

7. IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING MANAGEMENT

COVID‐19 outbreak reminded us that we live in an unpredictable world. The management of health care institutions faced challenges. Nursing managers can benefit from this study to determine the problems that may arise during this period when the epidemic continues to spread rapidly and after it is brought under control. Given that nurses' experiences in the MERS outbreak were associated with their intention to provide care to patients with a newly emerging infectious disease (Oh et al., 2017), it is hoped that the results of our study will also be useful for future outbreaks. Hospital managers can use this study as a guide to re‐organise institutional policies to meet the needs and expectations of nurses. Kisely et al. (2020) reported that, despite the wide variety of settings and types of viral outbreaks, useful interventions consistently reported to minimize distress of health care workers were similar and generally related to communication, adequate equipment, rest and both practical and psychological support. There are similar implications for institutional and nursing managers in our study. According to our findings, nurses should also be made to feel that they are primarily valuable members of the institution and qualified professionals first, not victims or heroes. Much attention should be paid to showing that managers are aware of and care about nurses’ labour and that a supportive work environment is created and maintained. Workload, wages and rewards should be fairly distributed. It is essential to take concrete steps to improve organisational justice. It is also crucial for policymakers to take and implement fair decisions by protecting and improving the workforce of nurses. Respectful communication, trust and the strength of a collaborative spirit are critical in times of crisis.

8. ETHICAL DECLARATION

This study has been approved by the Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University Human Research Ethics Committee (institution numbered 2020/05).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NY contributed substantially to the conception of the study and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing the major portion of the paper. AA contributed substantially to the interpretation of the results, data collection and writing the paper. MB contributed substantially to the design, data collection and analysis of data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank participants for their cooperation.

Yıldırım N, Aydoğan A, Bulut M. A qualitative study on the experiences of the first nurses assigned to COVID‐19 units in Turkey. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29:1366–1374. 10.1111/jonm.13291

Funding information

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- Aboul‐Ela, G. M. B. (2014). Analyzing the relationships between organization justice dimensions and selected organizational outcomes‐empirical research study. International Journal of Business and Economic Development, 2(3), 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y. , Lin, C. C. , Lin, C. Y. , Chen, J. Y. , Chue, C. M. , & Chou, P. (2004). Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatric Services (Washington. D.C.), 55(9), 1055–1057. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, T. , Huang, X. , Wang, L. , Li, B. , Dong, X. , Lu, H. , Wan, Q. , & Shang, S. (2020). Effects of organisational justice, work engagement and nurses' perception of care quality on turnover intention among newly licensed registered nurses: a structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2626–2637. 10.1111/jocn.15285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. S. , & Kim, J. S. (2018). Factors influencing emergency nurses' ethical problems during the outbreak of MERS‐CoV. Nursing Ethics, 25(3), 335–345. 10.1177/0969733016648205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley, A. , Hammond, N. E. , & Fraser, J. F. (2010). The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 Influenza pandemic of 2009: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(5), 577–585. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galehdar, N. , Kamran, A. , Toulabi, T. , & Heydari, H. (2020). Exploring nurses' experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID‐19: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 489. 10.1186/s12888-020-02898-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gören, Ş. , & Şahi̇noğlu, S. (2018). The nurse phenomenon in Turkish cinema. DEUHFED, 11(3), 250–256. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/deuhfed/issue/46781/586633 [Google Scholar]

- Hashish, E. (2019). Nurses' perception of organizational justice and its relationship to their workplace deviance. Nursing Ethics, 27(1), 273–288. 10.1177/0969733019834978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Q. , Li, T. , Su, Y. , & Luan, Y. (2021). Instructive messages and lessons from chinese countermarching nurses of caring for COVID‐19 patients: A qualitative study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 32(2), 96–102. 10.1177/1043659620950447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2020). Press information. Press Information. Retrieved from https://www.icn.ch/news/icn‐confirms‐1500‐nurses‐have‐died‐covid‐19‐44‐countries‐and‐estimates‐healthcare‐worker‐covid [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, Z. , Fereidouni, Z. , Behnammoghadam, M. , Alimohammadi, N. , Mousavizadeh, A. , Salehi, T. , Mirzaee, M. S. , & Mirzaee, S. (2020). The lived experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID‐19 in Iran: A phenomenological study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 13, 1271–1278. 10.2147/RMHP.S258785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaynar Şi̇mşek, A. & Ecevi̇t Alpar, Ş. , (2019). Image perception of the society for nursing profession: Systematic review. SAUHSD, 2(1), 32–46. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/sauhsd/issue/45374/516746 [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. (2017). Nurses' experience of middle east respiratory syndrome patients care. Journal of the Korea Academia‐Industrial Cooperation Society, 18(10), 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. (2018). Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control, 46(7), 781–787. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely, S. , Warren, N. , McMahon, L. , Dalais, C. , Henry, I. , & Siskind, D. (2020). Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review and meta‐analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 369, m1642. 10.1136/bmj.m1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J. , Ma, S. , Wang, Y. , Cai, Z. , Hu, J. , Wei, N. , Wu, J. , Du, H. , Chen, T. , Li, R. , Tan, H. , Kang, L. , Yao, L. , Huang, M. , Wang, H. , Wang, G. , Liu, Z. , & Hu, S. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Liu, S. M. , Yu, X. H. , Tang, S. L. , & Tang, C. K. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Current status and future perspectives. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 55(5), 105951. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. , Luo, D. , Haase, J. E. , Guo, Q. , Wang, X. Q. , Liu, S. , Xia, L. , Liu, Z. , Yang, J. , & Yang, B. X. (2020). The experiences of health‐care providers during the COVID‐19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. The Lancet. Global Health, 8(6), e790–e798. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maben, J. , & Bridges, J. (2020). COVID‐19: Supporting nurses' psychological and mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15–16), 2742–2750. 10.1111/jocn.15307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, R. (2004). The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: Lessons learned. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 359(1447), 1117–1125. 10.1098/rstb.2004.1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B. (2018). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey‐Bass Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, R. , Rodriguez, A. , & King, N. (2015). Colaizzi’s descriptive phenomenological method. The Psychologist, 28(8), 643–644. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, N. , Hong, N. , Ryu, D. H. , Bae, S. G. , Kam, S. , & Kim, K.‐Y. (2017). Exploring nursing intention, stress and professionalism in response to infectious disease emergencies: The experience of local public hospital nurses during the 2015 MERS outbreak in South Korea. Asian Nursing Research, 11(3), 230–236. 10.1016/j.anr.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.‐S. , Lee, E.‐H. , Park, N.‐R. , & Choi, Y. H. (2018). Mental health of nurses working at a government‐designated hospital during a MERS‐CoV outbreak: A cross‐sectional study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(1), 2–6. 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiró, T. , Lorente, L. , & Vera, M. (2020). The COVID‐19 crisis: Skills that are paramount to build into nursing programs for future global health crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6532. 10.3390/ijerph17186532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poortaghi, S. , Shahmari, M. , & Ghobadi, A. (2021). Exploring nursing managers' perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID‐19: A content analysis study. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 27. 10.1186/s12912-021-00546-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti, E. , Di Mattei, V. , Perego, G. , Ferrari, F. , Mazzetti, M. , Taranto, P. , Di Pierro, R. , Madeddu, F. , & Calati, R. (2020). The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(8), 43. 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şenol Çelik, S. , Atlı Özbaş, A. , Çelik, B. , Karahan, A. , Bulut, H. , Koç, G. , Çevik Aydın, F. , & Özdemir Özleyen, Ç. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic: Turkish Nurses Association. HEAD, 17(3), 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Seyrek, H. , & Ekici, D. (2017). Nurses’ perception of organizational justice and its effect on bullying behaviour in the hospitals of Turkey. Hospital Practices and Research, 2(3), 72–78. 10.15171/hpr.2017.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Q. , Zhang, X. , Wang, X. , & Cai, C. (2020). The influence of experiences of involvement in the COVID‐19 rescue task on the professional identity among Chinese nurses: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1662–1669. 10.1111/jonm.13122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, R. , Yu, T. , Luo, K. , Teng, F. , Liu, Y. , Luo, J. , & Hu, D. (2020). Experiences of clinical first‐line nurses treating patients with COVID‐19: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(6), 1381–1390. 10.1111/jonm.13095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Ministry of Health (2020). COVID‐19 information page. Retrieved from https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/

- Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology, 3rd ed. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) homepage. Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/

- Xiang, Y. T. , Yang, Y. , Li, W. , Zhang, L. , Zhang, Q. , Cheung, T. , & Ng, C. H. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(3), 228–229. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, A. , & Şimşek, H. (2016). Qualitative research methods in social sciences, 10th ed. Seçkin Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, M. , Gölbaşı, Z. , Erturhan Türk, K. , Topal Hançer, A. (2019). Nurses, physicians, and patients' views on the image of nursing. Journal of Cumhuriyet University Health Sciences Institute, 4(2), 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X. , & Zeng, L. (2020). A study on the psychological needs of nurses caring for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 from the perspective of the existence, relatedness, and growth theory. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 7(2), 157–160. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]