Abstract

Previous studies have indicated that the generation of newborn hippocampal neurons is impaired in the early phase of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A potential therapeutic strategy being pursued for the treatment of AD is increasing the number of newborn neurons in the adult hippocampus. Recent studies have demonstrated that ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) plays a neuroprotective role by preventing memory loss in many neurodegenerative diseases. However, the extent of EGb 761’s protective role in the AD process is unclear. In this study, different doses of EGb 761 (0, 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg; intraperitoneal injections once every day for four months) were tested on 5×FAD mice. After consecutive 4-month injections, mice were tested in learning memory tasks, Aβ, and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (DG) of hippocampus and morphological characteristics of neurons in DG of hippocampus. Results indicated that EGb 761 (20 and 30 mg/kg) ameliorated memory deficits. Further analysis indicated that EGb 761 can reduce the number of Aβ positive signals in 5×FAD mice, increase the number of newborn neurons, and increase dendritic branching and density of dendritic spines in 5×FAD mice compared to nontreated 5×FAD mice. It was concluded that EGb 761 plays a protective role in the memory deficit of 5×FAD mice.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, ginkgo biloba exact, neurogenesis, memory, Aβ

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease associated with the death of neural cells of brain and memory dysfunction. The disease is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for up to 70% of cases with half the population over 80 years of age suffering from the disease. Clinical observation has shown that progressive memory impairment is the primary symptom of AD, which is thought to be the consequence of the selective degeneration of nerve cells in brain regions critical for memory, cognitive function, and personality [1]. However, the etiology of AD is unclear and there is no effective therapeutic to prevent or cure the disease, so there is an urgent need for efforts to find an efficient cure.

Previous studies indicated that neural stem cells or neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the dentate gyrus (DG) produced newborn neurons throughout life via a process called neurogenesis [2]. These newborn neurons in the DG incorporated into the existing neural granule cell network and contributed to hippocampus-dependent functions such as learning and memory [3]. Studies have reported an age-related decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis, accompanied by cognitive impairment [4]. Postmortem studies of the aging process of most AD patients, in contrast to the normal aging process, display aberrant structural alterations in the hippocampal region [5]. In animal models of AD, such as 5×FAD mice, proliferating neuron numbers, labeled by 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), are also reduced [6]. Furthermore, studies have shown that amyloid-beta protein (Aβ) isolated from early-onset familial AD patients inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of cultured human and rodent NPCs by promoting apoptosis of these cells [7]. This suggests that the inhibition of Aβ toxicity and restoration of hippocampal neurogenesis are potential pharmacological targets for treating AD.

Ginkgo biloba is a medicinal herb that has been used as a traditional Chinese medicine for several thousand years. EGb 761 is a dry extract from Ginkgo biloba leaves that contains two active components: ginkgo flavonoids (22-27%) and terpene lactones (5-7%) [8,9]. In clinical studies, EGb 761 is often prescribed as an anti-dementia drug, administered at a dose similar to cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. In preclinical studies, EGb 761 exhibited multiple anti-AD effects. EGb 761 has been shown to inhibit free circulating and intracellular cholesterol levels and to facilitate metabolism of beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) and amyloidogenesis by enhancing α-secretase activity, thus reducing the levels of APP in brain [10]. EGb 761 also displays neuroprotective effects through the inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A (2) after acute spinal cord injury [11]. However, it remains unclear whether EGb 761 has a protective effect against AD progression and improves cognitive function.

In the current study, the effects of EGb 761 were tested in 5×FAD mice with regard to the following three aspects: 1) the effects of EGb 761 on hippocampus-dependent learning and memory in the Morris Water Maze (MWM) and novel object recognition test; 2) the effects of EGb 761 on neurogenesis in the DG of 5×FAD mice; and 3) the histological effects of EGb 761 on hippocampus.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experiments were conducted on 4-month-old male mice (Shanghai Experimental Animal Center, China). Breeding trios were used to maintain the colony. In this experiment, transgenic mice (Tg, 5×FAD, n = 48) and negative littermate mice (wild type [WT], n = 12) were used. Tail biopsies of mice were collected for genotyping at 4 weeks of age. Mice of experimental groups were housed 4 per cage and were kept under standard conditions (12:12 h light/dark cycle, 21 ± 2°C; relative humidity, 40%). Mice were given ad libitum access to food and water. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Xuzhou Medical University Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were made to reduce the number of animals used and to treat the animals humanely to minimize their pain and suffering. Mice experiments were approved by the Xuzhou Medical University Animal Ethics Committee (protocol number: #20180522141M).

Transgenic mice

Genotyping was performed by PCR (oligonucleotides: sense [5’GGACTGACCACTCGACCAG] and anti-sense [CGGGGGTCTAGTTCTGCAT]). The expected band size of the transgene was 377 bp. An internal positive control was also selected (oligonucleotides: sense [CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT] and anti-sense: [GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC]), in which the expected band size of the transgene was 324 bp (wild type; 608 bp). A general PCR process was used to amplify the cDNA (2 min at 93°C; 3 cycles of 15 sec at 93°C, 30 sec at 55°C, 30 sec at 72°C; 2 cycles of 15 sec at 93°C, 30 sec at 60°C, 30 sec at 72°C; and 30 cycles of 15 sec at 93°C, 30 sec at 66°C, 30 sec at 72°C).

Drugs and treatment

Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (ID#: 05485001) and dissolved in saline. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with HCl. Different doses of EGb 761 (0, 10, 20 and 30 mg/kg) were selected from previous reports that showed neuroprotective effects of EGb in mice [12]. To detect whether the EGb 761 played a protective role during the AD procedure, the Tg mice were injected intraperitoneally with different doses of EGb 761 once every day for four months. Littermates were used as the negative control for this experiment. After consecutive EGb 761 treatment, the animals were divided into three groups for memory test (group 1), neurogenesis and Aβ detection (group 2), and neuronal morphological characteristics in hippocampus regions (group 3). Abilities of learning memory for animals (group 1) were measured by the novel object recognition (NOR) and MWM tests. Animals of group 2 were equally divided into two parts (4 mice per part) for the neurogenesis and Aβ detection, including the amyloidosis in the hippocampus region. Group 3 was used for Golgi staining to test the morphological characteristics of the DG.

Cognitive ability tests

NOR

To reduce the stress effects from water on learning memory, the testing order in mice was NOR and then MWM. The NOR was used to assess nonspatial working memory. In the training session, the mice were presented with two identical objects (2 small self-colored wood bricks) in a square arena (W50 × L50 × D30 cm) and allowed to habituate and explore for 15 min (same object trial). After the habituation, mice were returned to their home cages for a 30 min break. Then, one of the two familiar wood bricks was replaced with a novel object (a similar wood brick with zebra stripes). The mice were again allowed to explore the objects for 15 min (choice trial). The novel object was randomly placed on either side of the arena. Object exploration was defined as each instance in which a mouse’s nose or forelimb touched the object or was oriented toward and within 2 cm of the object [13]. When animals investigated an object, the time spent on each side was recorded by the computer.

MWM

The MWM test was performed between 10:00 and 15:00 as previously described [14]. MWM training trials were carried out after the last injection. The MWM apparatus was 100 cm in diameter and filled with water at 22 ± 1°C. Prominent visual cues were placed on the walls around the apparatus. Some opaque powders were placed in the water to hide the platform. During the training, a platform was placed 1 cm below the surface of the water and located approximately 15 cm from the edge of the tank. The starting position was randomized among four quadrants of the pool every day, and each mouse underwent four trials per day lasting for 5 days with inter-trial intervals of 1 min between different trials. The mouse was allowed 90 s to swim and freely find the platform and then remain on the platform for 30 s. If the mouse did not locate the platform in the 90 s, it was gently guided to the platform and allowed to remain there for 30 s. At the end of each trial, the mice were dried in the incubator and returned to their home cage until the next trial. A total of 24 hours after the memory acquisition trials, memory was detected. During this trial, the mice were allowed to swim in the pool without the platform for 90 s. The latency to reach the platform site (target) and the number of crossings of the targeting quadrant were recorded by a camera on the ceiling. The footage was analyzed by Any-Maze software (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL).

Neurogenesis in hippocampus

After the mice received consecutive EGb 761 injections, they (n = 4) were given one intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (50 mg/kg) to detect neurogenesis in the DG of hippocampus. BrdU was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl at a concentration of 25 mg/ml, and the solution was filter-sterilized before injection. Staining for BrdU was performed according to previously published procedures [15]. After rinsing with 0.01 M PBS (3 min × 3), partial denaturation of DNA was carried out with 2N HCl at 40°C for 15, 30 or 60 min. Afterward, slides were washed in 0.5% Triton X-100 in 0.01 M PBS. Then, the slices were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The next day, the primary antibody was detected with the second antibody conjugated to Alexa 488 (1:500, Abcam, USA) or Alexa 594 and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Images were captured using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative analysis of the BrdU-positive cells was carried out using a modified unbiased stereology protocol used in quantifying adult-born neurons of the DG [16]. The number of positive-signal cells were counted by two observers who were blind to grouping and experimental designing. The number of positive cells per group was averaged and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Immunofluorescence staining

To assess the protective effects from EGb 761, the Aβ expression in the hippocampus region was detected in independent groups (4 mice per group). As mentioned above, the Aβ signals in DG of hippocampus region were qualified by the immunofluorescent staining in 8-month-old Tg or control mice. In the experiment, a 6E10 primary antibody (Cat.803015, Biolegend) was used to detect the Aβ signal, and Alex488 was used as the second antibody. Images were captured using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Aβ ELISA

Mice brain tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer, including the 50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaF, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM sodium vanadate, 8.5% sucrose, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μg/ml leupeptin, and 5 μg/ml pepstatin. Then, the homogenates were centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Soluble fractions were dissolved into the supernatant. After separating the supernatant, the soluble fractions were collected. Following this, ELISA kits were used to detect the soluble Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 concentrations of the manufacturer’s protocol (Shanghai Shengon BioTech).

Thioflavin-S staining (ThS)

To assess the amyloidosis in the model, ThS staining was used 4 months after the EGb 761 treatment. ThS was dissolved in DMSO to obtain a 0.1 M stock solution. The slices were incubated in the ThS solution for 20 min. After the gradient dehydration, ThS fluorescence was captured by the microscope.

Golgi staining of hippocampus

To evaluate the protective contribution of EGb 761 to neurons at the morphological level, Golgi staining of CA1 neural cells was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions [17]. First, freshly dissected brains from the 30 mg/kg EGb 761 group and controls (four brain tissues every groups) were impregnated at room temperature for 14 days in Solution A and Solution B, and then they were bathed in Solution C at 4°C for 2 days. Then, brain tissues were sectioned into 200 μm sections and transferred onto 2% gelatin-coated slides. These sections were dried at room temperature for 3 days and then stained with Solution D, Solution E, and distilled water for 30 min following gradient dehydration with 75%, 95%, and 100% ethanol. Sections were analyzed using the Image J software package and Sholl analysis. Dendritic morphology was analyzed with a 100 × objective lens. Sholl analysis was performed to quantify the number of dendritic branches and measure dendritic length at concentric 10-μm intervals.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with 13.0 SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 13). All data are presented as mean ± SD. For behavioral and immunohistochemistry data, comparisons between groups were performed using one-way ANOVA for groups with one independent variable followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test. A value of P < 0.05 (*) was considered to be significant. “ns” indicates no significant difference.

Results

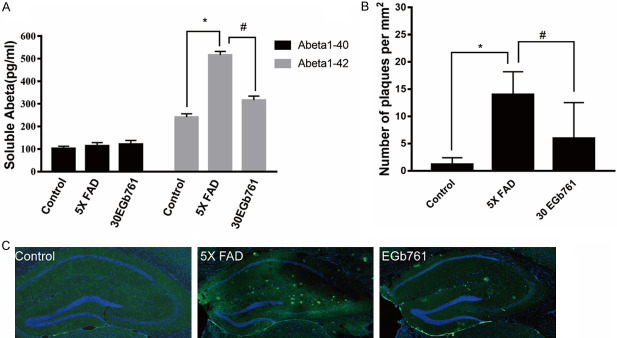

Effect of EGb 761 on nonspatial learning memory and spatial memory in the MWM

The effect of one month of EGb 761 administration on nonspatial memory was tested in the cognitive object recognition paradigm. Time spent exploring each of the objects was recorded and expressed as a percentage of the total exploration time. After training day (Figure 1A), the 5×FAD group showed less significant exploring behavior toward the novel object than the control group (P < 0.05), indicating that these animals were unable to remember the original block. In contrast, EGb 761-treated groups (10, 20, and 30 mg/kg) spent significantly more time exploring the novel object compared to the primary object (F (4, 35) = 3.194, P < 0.05). Of note, the animals in the 30 mg/kg group showed a significantly enhanced preference index compared to the 5×FAD group.

Figure 1.

Effect of EGb 761 on nonspatial learning memory in NOR and spatial memory in MWM. A. Effect of EGb 761 improved the memory of NOR in Tg mice. B. Escape latencies. C. The number of platform crossings. D. The percentage of time spent searching in the target quadrant where the platform had been located by individual mice in the treatment groups. Data are represented as mean ± SD. * indicates P < 0.05; # indicates P < 0.05.

After the novel objection test was conducted, the spatial memory of all animals was trained in MWM. For the escape time test, there was a significant main effect among the groups [F (4, 35) = 8.91; P < 0.01]. This was followed by post hoc analysis indicating that 5×FAD mice needed more time to escape (Figure 1B, P < 0.05) when compared with the control mice. Further analysis showed that both the 20 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment (P < 0.05) and 30 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment (P < 0.05) reduced the escape time in the 5×FAD mice. During the platform crossing time test (reversal learning), there was a significant main effect among the groups [Figure 1C and 1D, F (4, 35) = 8.413; P < 0.05]. Post hoc analysis indicated that 5×FAD mice spent less time in crossing (P < 0.05) compared with control mice. Further analysis showed that both the 20 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment (P < 0.05) and 30 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment (P < 0.05) increased the crossing time in 5×FAD mice. 5×FAD mice spent less time in the target quadrant (< 25%) compared to the control group, indicating that the memory of 5×FAD mice was impaired (< 25%). EGb 761 treatments improved the animals’ memory, leading to increased time spent in the target quadrant. The 30 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment made the mice spend more time in the target quadrant (> 25%). These results indicated that EGb 761 enhanced spatial memory of the 5×FAD mice in the MWM.

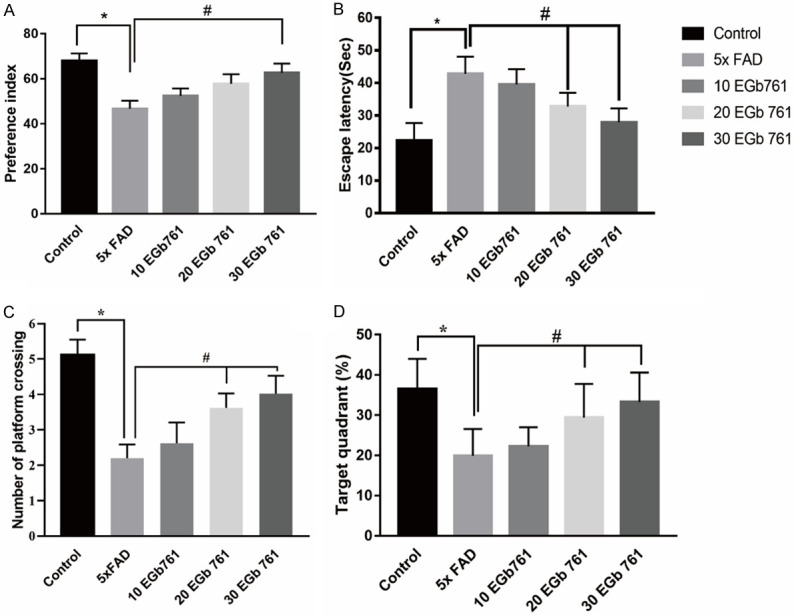

Effect of EGb 761 on the proliferation of newborn neurons in hippocampus of 5×FAD mice

Previous studies reported that the number of newborn cells decreased with aging and in animal models of AD [18]. Newborn cells from the DG field were labeled with BrdU in the current study. The contribution of newborn neurons affected by the EGb 761 treatment was explored in 5×FAD mice. The experiments showed that the number of BrdU-positive cells in every unit was 90.10 ± 25.8 and 151.9 ± 45.1 in the DG of hippocampus of 5×FAD and WT mice, respectively. After EGb 761 treatment, the histology showed a significant main effect of EGb 761 treatment [F (4, 35) = 5.7, P = 0.001]. Post hoc analysis (LSD) indicated that the number of BrdU-positive cells in the 20 mg/kg EGb 761/5×FAD mice and 30 mg/kg EGb 761/5×FAD mice were increased to levels approaching that of the WT mice (Figure 2A and 2B). To further explore whether the proliferative cells enhanced memory ability, we examined our data (Figure 2C and 2D). The data indicated that the number of DCX+ cells in the DG of 5×FAD mice was decreased in contrast with those of the control mice (P < 0.05). However, the chronic 30 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment could reverse the effect where the number of DCX+ cells decreased in the 5×FAD mice (P < 0.05). Thus, chronic EGb 761 treatment can improve impaired memory ability in 5×FAD mice by increasing the proliferation of newborn neurons in hippocampus.

Figure 2.

Effects of EGb 761 on neurogenesis in hippocampus of 5×FAD mice. A. Representative images of BrdU+ cells in the DG (20×). B. Density of BrdU+ cells in the DG. C. Representative images of DCX+ cells in the CA1 (20×). D. Density of DCX+ cells in the DG. The number of DCX+ cells in the CA1 of 5×FAD mice were decreased in contrast with control mice (P < 0.05). Chronic 30 mg/kg EGb 761 treatment could increase the number of DCX+ cells in the 5×FAD mice. * indicates P < 0.05 vs. control. # indicates P < 0.05 vs. 5×FAD group. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

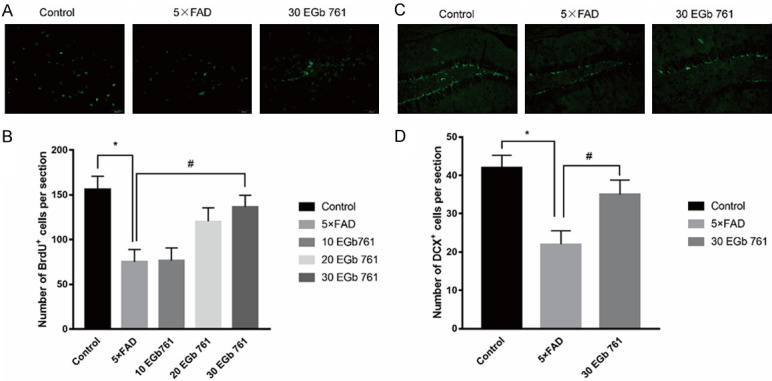

Effect of EGb 761 on Aβ expression in hippocampus of 5×FAD mice

To verify whether the improvement of cognitive deficits by EGb 761 treatment is related to the change of Aβ accumulation in the hippocampus region of 5×FAD mice, hippocampal Aβ was analyzed using ELISA and immunofluorescence. As shown in Figure 3B and 3C, the Aβ positive signals in the DG were significantly increased using 6E10 primary antibody in 8-month-old Tg mice compared with age-matched control mice; in the latter, the signals may have been inhibited by the EGb 761 treatment. Furthermore, ELISA of Aβ (Figure 3A) was performed to determine soluble Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 in brain of mice. No significant difference in soluble Aβ1-40 was found in Tg mice, control mice, and EGb 761 groups (P > 0.05), but a significant difference was found in the soluble Aβ1-42 level (P < 0.05). This indicated that the soluble Aβ1-42 level was increased in the Tg mice in contrast with control mice, and EGb 761 treatment reduced the soluble Aβ1-42 level of brain.

Figure 3.

Effect of EGb 761 on Aβ expression in hippocampus of 5×FAD mice. A. Soluble Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 from brains of 8-month-old mice were measured using ELISA. B, C. Representative immunofluorescence images of Aβ deposits (6E10) and number (g) of Aβ deposits. Data shown are the means ± SEM, with 4 mice in each group. * indicates P < 0.05 vs. control. # indicates P < 0.05 vs. 5×FAD group. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

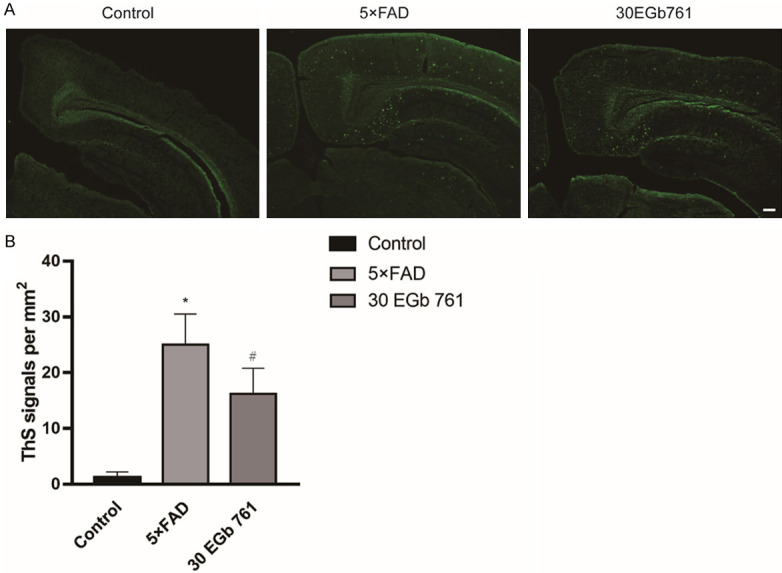

Effect of EGb 761 on ThS expression in hippocampus of 5×FAD mice

To further estimate the protective role of EGb 761 in Tg mice, the number of ThS-positive signals in the hippocampal DG region were analyzed. Results showed that ThS-positive signals in the DG were significantly increased in 8-month-old Tg mice compared with age-matched control mice (Figure 4, P < 0.05). However, the EGb 761 treatment reduced the ThS-positive signals in the DG in Tg mice.

Figure 4.

Effect of EGb 761 on the ThS positive signals in the hippocampal DG region of 5×FAD mice. A. Representative immunofluorescence images of ThS-positive signal. B. EGb 761 inhibits the ThS positive signals in the hippocampal DG region of 5×FAD mice. Data shown are the means ± SD, with 4 mice in each group. * indicates P < 0.05 vs. control. # indicates P < 0.05 vs. 5×FAD group.

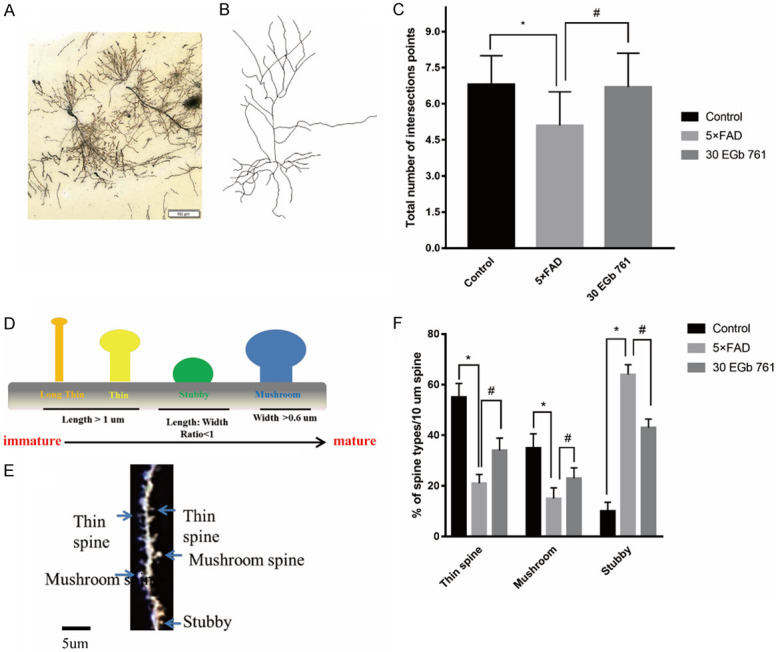

Dendritic morphology

In this study, a total of 30 hippocampal pyramidal neurons in CA1 were selected from the controls (n = 10), 5×FAD mice (n = 10), and 5×FAD mice treated with 30 mg/kg EGb 761 (n = 10) to analyze morphological changes. Contrasts of dendritic length and Sholl’s analysis parameters were also obtained from controls (n = 10), 5×FAD mice (n = 10), and EGb 761-treated 5×FAD mice (n = 10). It was found (Figure 5) that the total number of dendritic branches close to the cell body in 5×FAD mice were lower than those of control mice (F (2, 27) = 20.44, P < 0.001). However, EGb 761 treatment increased the total length of dendrites (P < 0.05). Similarly, the reduced basilar dendritic trees in the dendritic branch point of 5×FAD mice were reversed significantly by EGb 761 treatment. Sholl’s analysis indicated that the intersections in the CA1 field of 5×FAD mice were impaired when contrasted with those of control mice (P < 0.05). However, EGb 761 (30 mg/kg) reversed these effects (P < 0.05) when contrasted with those of the 5×FAD mice.

Figure 5.

The effect of EGb 761 on the dendritic morphology of hippocampal CA1 neurons. A. Representative images of spine density in hippocampus. Scale bar = 100 μm. B. Representative images of dendritic branches in hippocampus. C. Analysis of branch number in hippocampus. D. Dendritic spine types found in the CA1 field. Spine maturity progresses (from left to right) from long, thin spine structures (yellow) to wide-headed mushroom spines (blue). Geometric characteristics of spines are listed below for each type. E. Golgi-stained secondary dendritic branch of a CA1 field neuron in mouse. Different spine types are indicated by arrowheads, which are color-coded to match. Scale bar, 5 um. F. The percentages of different types of spines treated by 30 EGb 761. Number of mature spines in 5×FAD mice were significantly decreased in contrast with those of control mice (P < 0.05). This can be reversed by 30 mg/kg EGb 761 choronic treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. * indicates a significant difference between groups (P < 0.05).

Discussion

For a long time, ginkgo biloba has been used as a medicinal herb in traditional Chinese medicine. EGb 761 is a mixture extracted from gingko biloba leaves [24]. This study demonstrated that ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 improves the memory ability in 5×FAD mice. The experimental results indicated that EGb 761 exerts a neuroprotective effect by increasing the number of newborn cells in the DG field and inhibiting Aβ pathology, especially reducing the Aβ1-42 level of brain. First, the results of this study showed that long-term treatment of Tg mice with EGb 761 improves spatial working memory and nonspatial working memory. Second, they demonstrated that long-term treatment of Tg mice with EGb 761 increased the number of newborn cells in the DG of hippocampus. These results suggested that EG 761 enhances cognitive function in the 5×FAD animal model of AD. Finally, the long-term treatment of Tg mice with EGb 761 can reduce the Aβ1-42 level of brain and amyloid-β (Aβ) of DG region. In general, our results provided new insights into the role of EGb 761 in AD.

AD is the most common neurodegenerative disease among the senior population. It is characterized by the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and the accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles in neurons [19]. The 5×FAD mouse model is a transgenic animal model of AD that overexpresses both mutant human APP (695) with the Swedish (K670N, M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) familial AD (FAD) mutations and human PS1 protein harboring two FAD mutations, M146L and L286V, under the control of the mouse Thy1 promoter [20]. In this animal model, mutant Aβ1-42 is exclusively generated and rapidly accumulates into massive levels in the mouse cerebrum. This induces amyloid plaque formation, neurodegeneration, and behavioral dysfunction. Further, in the model, 5×FAD mice show severe impairment of learning and memory, as suggested by different behavioral tests [21].

EGb 761 is a clinically available and well-tolerated herbal medication that consists of two active components: flavonoid glycoside and terpene lactone [22]. Many studies on its toxicological and pharmacological properties have indicated that EGb 761 has neuroprotective effects in aging-related diseases [23]. Kwon et al. found that EGb 761 can inhibit zinc-induced tau phosphorylation at Ser262 through its anti-oxidative actions involving the regulation of GSK3β [24]. As such, EGb 761 has been widely used in the prevention and treatment of aging-related diseases. The molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of EGb 761 remain unknown. A previously proposed mechanism of the neuroprotective functions of EGb 761 suggested that it prevents activation of mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathways [25,26]. In this study, EGb 761 was found to improve learning and memory in spatial and nonspatial memory tasks and to play a neuroprotective role in the 5×FAD mouse model. Notably, in in vitro studies, mouse cerebral microvessel endothelial cells incubated with Aβ were used to study EGb 761’s effects on the blood brain barrier in AD. Results indicated that EGb 761 significantly decreases cell viability and apoptosis in response to incubation with Aβ1-42 oligomer [27]. Our (unpublished) data and another lab’s data also suggest that EGb 761 inhibits Abeta oligomerization and Abeta deposits in vivo [28].

Although the relationship between newborn neuron proliferation in the adult hippocampus and neurodegenerative disease progression is not clear, aging-associated hippocampal neurogenesis reduction may contribute to cognitive impairment. Ginkgo biloba treatment has been found to significantly enhance the expression of doublecortin (DCX), a micro-tubular marker of neurogenesis, in comparison to controls. These results indicate a beneficial role of ginkgo biloba in hippocampal neurogenesis in the context of brain aging [29]. Ginkgo biloba is also known to improve blood flow and protect tissue from free radical damage [30]. Recently, several studies demonstrated that cell proliferation decreased in the DG of hippocampus in a number of AD mouse models that exhibited amyloid deposition [31]. Additionally, the impairing neurogenesis processes in the SVZ were reported in AD models [32]. In general, some reports suggested that diminished neurogenesis in 5×FAD mice was involved in memory decline [33]. In this study, 5×FAD mice treated for four months with EGb 761 showed enhanced capacity for neurogenesis. This suggests that EGb 761-induced memory function improvement of 5×FAD mice may be related to increased neurogenesis.

Next, it should be discussed why the cell activation and morphology of DG were chosen to illustrate that the Egb 761 improved the memory of 5×FAD mice. DG field is a key output node of the hippocampal memory circuit, which can project the widespread areas of brain [34]. It was reported that DG of hippocampus is involved in various kinds of functions, such as novelty detection and spatial memory. DG was more susceptible and vulnerabilities field that was affected in the AD by redistributing information from DG across a greater number of output neurons [35]. DG is also a vital field of hippocampus that contributes to the formation of new episodic memories [36]. Animals with destroyed DG show memory impairment. DG in adult-born mice may influence the precision of remote memories through replay. Therefore, the DG is appropriate for field testing different spatial memories between control and AD mice.

Conclusion

This experiment found that a one-month EGb 761 treatment improved spatial and nonspatial working memory of 5×FAD mice. The treatment also enhanced neurogenesis, indicating the potential therapeutic value of EGb 761 in neurogenesis-associated and/or neurodegenerative neurological disorders.

Acknowledgements

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501185), Shandong Provincial Key Research & Development Project (2017GSF218043), the Open Projects of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of New Drug Research and Clinical Pharmacy (grant number KF-XY201407), the Yantai Science and Technology Planning Project (grant number 2016WS017), the Key Research and Development Project of Anhui Province (202004j07020014) and the Hefei Science and Technology Bureau “Borrow, Transfer and Supplemen” Project (J2019Y01).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Cooper S, Greene JD. The clinical assessment of the patient with early dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(Suppl 5):v15–24. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.081133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenbosch R, Borgs L, Beukelaers P, Belachew S, Moonen G, Nguyen L, Malgrange B. Adult neurogenesis and the diseased brain. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:652–666. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toda T, Parylak SL, Linker SB, Gage FH. The role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in brain health and disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:67–87. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stagni F, Giacomini A, Emili M, Uguagliati B, Bonasoni MP, Bartesaghi R, Guidi S. Subicular hypotrophy in fetuses with down syndrome and in the Ts65Dn model of down syndrome. Brain Pathol. 2019;29:366–379. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seki T, Arai Y. Age-related production of new granule cells in the adult dentate gyrus. Neuroreport. 1995;6:2479–2482. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199512150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yue J, Liang C, Wu K, Hou Z, Wang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Yang H. Upregulated SHP-2 expression in the epileptogenic zone of temporal lobe epilepsy and various effects of SHP099 treatment on a pilocarpine model. Brain Pathol. 2020;30:373–385. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Gu GJ, Zhang Q, Liu JH, Zhang B, Guo Y, Wang MY, Gong QY, Xu JR. NSCs promote hippocampal neurogenesis, metabolic changes and synaptogenesis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Hippocampus. 2017;27:1250–1263. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haughey NJ, Nath A, Chan SL, Borchard AC, Rao MS, Mattson MP. Disruption of neurogenesis by amyloid beta-peptide, and perturbed neural progenitor cell homeostasis, in models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1509–1524. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gertz HJ, Kiefer M. Review about Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761 (Ginkgo) Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:261–264. doi: 10.2174/1381612043386437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S, Sharma S, Ranawat P, Nehru B. Modulatory effects of ginkgo biloba against amyloid aggregation through induction of heat shock proteins in aluminium induced neurotoxicity. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:465–490. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02940-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Z, Liu N, Huang J, Lu PH, Xu XM. Inhibition of cPLA2 activation by Ginkgo biloba extract protects spinal cord neurons from glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress-induced cell death. J Neurochem. 2011;116:1057–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rojas P, Serrano-Garcia N, Mares-Samano JJ, Medina-Campos ON, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Ogren SO. EGb 761 protects against nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurotoxicity in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinsonism in mice: role of oxidative stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K, Lu JM, Xing ZH, Zhao QR, Hu LQ, Xue L, Zhang J, Mei YA. Effect of 1.8 GHz radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation on novel object associative recognition memory in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44521. doi: 10.1038/srep44521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakhaie MH, Soleimani M, Pourheydar B, Majd Z, Atefimanesh P, Asl SS, Mehdizadeh M. Effects of extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields on neurogenesis and cognitive behavior in an experimental model of hippocampal injury. Behav Neurol. 2017;2017:9194261. doi: 10.1155/2017/9194261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csabai D, Cseko K, Szaiff L, Varga Z, Miseta A, Helyes Z, Czeh B. Low intensity, long term exposure to tobacco smoke inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis in adult mice. Behav Brain Res. 2016;302:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendell AL, Atwi S, Bailey CD, McCloskey D, Scharfman HE, MacLusky NJ. Expansion of mossy fibers and CA3 apical dendritic length accompanies the fall in dendritic spine density after gonadectomy in male, but not female, rats. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:587–601. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaudhuri A, Zangenehpour S, Rahbar-Dehgan F, Ye F. Molecular maps of neural activity and quiescence. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2000;60:403–410. doi: 10.55782/ane-2000-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauwers E, Lalli G, Brandner S, Collinge J, Compernolle V, Duyckaerts C, Edgren G, Haik S, Hardy J, Helmy A, Ivinson AJ, Jaunmuktane Z, Jucker M, Knight R, Lemmens R, Lin IC, Love S, Mead S, Perry VH, Pickett J, Poppy G, Radford SE, Rousseau F, Routledge C, Schiavo G, Schymkowitz J, Selkoe DJ, Smith C, Thal DR, Theys T, Tiberghien P, van den Burg P, Vandekerckhove P, Walton C, Zaaijer HL, Zetterberg H, De Strooper B. Potential human transmission of amyloid beta pathology: surveillance and risks. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:872–878. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, Berry R, Vassar R. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang LX, Huang GD, Su F, Wang H, Zhang C, Yu X. Vortioxetine administration attenuates cognitive and synaptic deficits in 5xFAD mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2020;237:1233–1243. doi: 10.1007/s00213-020-05452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EGb 761: ginkgo biloba extract, Ginkor. Drugs R D. 2003;4:188–193. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200304030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun R, Zhang H, Si Q, Wang S. Protective effect of Ginkgo biloba extract on acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in D-galactose aging rats. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2002;25:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon KJ, Lee EJ, Cho KS, Cho DH, Shin CY, Han SH. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) attenuates zinc-induced tau phosphorylation at Ser262 by regulating GSK3beta activity in rat primary cortical neurons. Food Funct. 2015;6:2058–2067. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00219b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian CJ, Kim YJ, Kim SW, Lim HJ, Kim YS, Choung YH. A combination of cilostazol and Ginkgo biloba extract protects against cisplatin-induced Cochleo-vestibular dysfunction by inhibiting the mitochondrial apoptotic and ERK pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e509. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An J, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Xie Y, Ke S, Liu L, Pan X, Chen Z. Exenatide alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive impairment in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2019;370:111932. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.111932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan WB, Cao L, Liu LM, Kalionis B, Chen C, Tai XT, Li YM, Xia SJ. EGb 761 provides a protective effect against Abeta1-42 oligomer-induced cell damage and blood-brain barrier disruption in an in vitro bEnd.3 endothelial model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y, Wu Z, Butko P, Christen Y, Lambert MP, Klein WL, Link CD, Luo Y. Amyloid-beta-induced pathological behaviors are suppressed by Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 and ginkgolides in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13102–13113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3448-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osman NM, Amer AS, Abdelwahab S. Effects of Ginko biloba leaf extract on the neurogenesis of the hippocampal dentate gyrus in the elderly mice. Anat Sci Int. 2016;91:280–289. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo DY, Nam Y, Kim W, Yoo KY, Park J, Lee CH, Choi JH, Yoon YS, Kim DW, Won MH, Hwang IK. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract on promotion of neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus in C57BL/6 mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;73:71–76. doi: 10.1292/jvms.10-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong H, Goico B, Martin M, Csernansky CA, Bertchume A, Csernansky JG. Modulation of hippocampal cell proliferation, memory, and amyloid plaque deposition in APPsw (Tg2576) mutant mice by isolation stress. Neuroscience. 2004;127:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veeraraghavalu K, Choi SH, Zhang X, Sisodia SS. Presenilin 1 mutants impair the self-renewal and differentiation of adult murine subventricular zone-neuronal progenitors via cell-autonomous mechanisms involving notch signaling. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6903–6915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0527-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang X, Tohda C. Heat shock cognate 70 inhibitor, VER-155008, reduces memory deficits and axonal degeneration in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:48. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cenquizca LA, Swanson LW. Spatial organization of direct hippocampal field CA1 axonal projections to the rest of the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaifosh P, Losonczy A. Mnemonic functions for nonlinear dendritic integration in hippocampal pyramidal circuits. Neuron. 2016;90:622–634. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller J, Watrous AJ, Tsitsiklis M, Lee SA, Sheth SA, Schevon CA, Smith EH, Sperling MR, Sharan A, Asadi-Pooya AA, Worrell GA, Meisenhelter S, Inman CS, Davis KA, Lega B, Wanda PA, Das SR, Stein JM, Gorniak R, Jacobs J. Lateralized hippocampal oscillations underlie distinct aspects of human spatial memory and navigation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2423. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04847-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]