Abstract

Background

Thrombocytopenia and thrombosis are prominent in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), particularly among critically ill patients; however, the mechanism is unclear. Such critically ill COVID‐19 patients may be suspected of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), given similar clinical features.

Objectives

We investigated the presence of platelet‐activating anti‐platelet‐factor 4 (PF4)/heparin antibodies in critically ill COVID‐19 patients suspected of HIT.

Patients/Methods

We tested 10 critically ill COVID‐19 patients suspected of HIT for anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies and functional platelet activation in the serotonin release assay (SRA). Anti‐human CD32 antibody (IV.3) was added to the SRA to confirm FcγRIIA involvement. Additionally, SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies were measured using an in‐house ELISA. Finally, von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen and activity were measured along with A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease with ThromboSpondin‐13 Domain (ADAMTS13) activity and the presence of anti‐ADAMTS13 antibodies.

Results

Heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia was excluded in all samples based on anti‐PF4/heparin antibody and SRA results. Notably, six COVID‐19 patients demonstrated platelet activation by the SRA that was inhibited by FcγRIIA receptor blockade, confirming an immune complex (IC)‐mediated reaction. Platelet activation was independent of heparin but inhibited by both therapeutic and high dose heparin. All six samples were positive for antibodies targeting the receptor binding domain (RBD) or the spike protein of the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. These samples also featured significantly increased VWF antigen and activity, which was not statistically different from the four COVID‐19 samples without platelet activation. ADAMTS13 activity was not severely reduced, and ADAMTS13 inhibitors were not present, thus ruling out a primary thrombotic microangiopathy.

Conclusions

Our study identifies platelet‐activating ICs as a novel mechanism that contributes to critically ill COVID‐19.

Keywords: antigen‐antibody complex, COVID‐19, heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, thrombosis

Essentials

-

•

Severe coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) can resemble heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

-

•

COVID‐19 patients referred for HIT testing were found to be negative for HIT.

-

•

Severe COVID‐19 sera demonstrate immune complexes that activate platelets through FcγRIIA signalling.

-

•

Severe COVID‐19 patients feature increased von Willebrand factor antigen and activity unrelated to ADAMTS13 antibodies.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is a highly transmissible viral infection caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) and has resulted in a global pandemic.1., 2. Critically ill patients with COVID‐19 can have prominent coagulation abnormalities, including mild thrombocytopenia and diffuse arterial and venous thrombosis.3., 4., 5., 6. While the mechanism is unclear, the clinical presentation shares many features of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), namely thrombocytopenia and thrombosis during critical illness.7

Heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia is a prothrombotic disorder that typically presents as thrombocytopenia related to heparin treatment and is associated with a high risk of thrombosis. HIT is caused by IgG‐specific antibodies targeting platelet‐factor 4 (PF4) that form immune complexes (IC) and cause platelet activation through the FcγRIIA receptor.8., 9. Recent reports have speculated that ICs also contribute to the pathobiology of severe COVID‐19.10 Retrospective analysis has shown that anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies are identified more frequently in COVID‐19 hospitalized patients compared to the general population.11 However, it is unclear if these contribute to platelet activation. In this report, we describe platelet‐activating ICs in critically ill COVID‐19 patients suspected of HIT. These ICs are not formed from IgG‐specific anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies and occur in conjunction with elevated von Willebrand factor (VWF) and anti‐COVID‐19 antibodies. Platelet‐activating ICs may thus be an additional mechanism contributing to severe COVID‐19.

2. STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

Blood samples from 10 critically ill patients with COVID‐19 were referred to the McMaster Platelet Immunology Laboratory (MPIL) for HIT testing. All samples sent for HIT testing are from patients with medium to high risk of HIT based on clinical presentation, including reduced platelet count, with or without thrombosis. Demographic data were obtained including age, sex, platelet nadir, heparin use, thrombotic event, admission diagnosis, and outcome (where available). Control samples included eight convalescent COVID‐19‐‐positive patients, five pre‐pandemic HIT‐positive samples (HIT), and seven pre‐pandemic healthy controls (HC).

Testing for anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies was done using an anti‐PF4/heparin enzymatic immunoassay (EIA, LIFECODES PF4 enhanced assay; Immucor GTI Diagnostics) for IgG, IgM, and IgA PF4‐heparin antibodies. If positive, an in‐house, IgG‐specific anti‐PF4/heparin EIA was performed.12 All samples were then tested for functional platelet activation in the serotonin release assay (SRA) with heparin (0, 0.1, 0.3, and 100 U/ml) as previously described. An anti‐human CD32 antibody (IV.3) was added to the SRA to confirm FcγRIIA engagement.13

Testing for IgG‐, IgA‐, and IgM‐specific antibodies against the receptor‐binding domain (RBD) and spike protein of SARS‐CoV‐2 virus was done using our in‐house ELISA, which has a sensitivity of 97.1% and a specificity of 98%.14

VWF antigen levels were assessed by the HemosIL von Willebrand Factor antigen automated chemiluminescent immunoassay (Instrumentation Laboratory). VWF activity was measured using the Innovance VWF Ac Assay (OPHL03; Siemens). A Disintigren And Metalloprotease with ThromboSpondin‐13 Domain (ADAMTS13) metalloproteinase activity and anti‐ADAMTS13 antibody were tested for all patients, as previously described, to determine whether VWF changes were related to ADAMTS13 activity.15 All testing was done using plasma from blood collected in sodium citrate. Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean and are analyzed by Student’s t test. Results are considered significant at P < .05.

This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

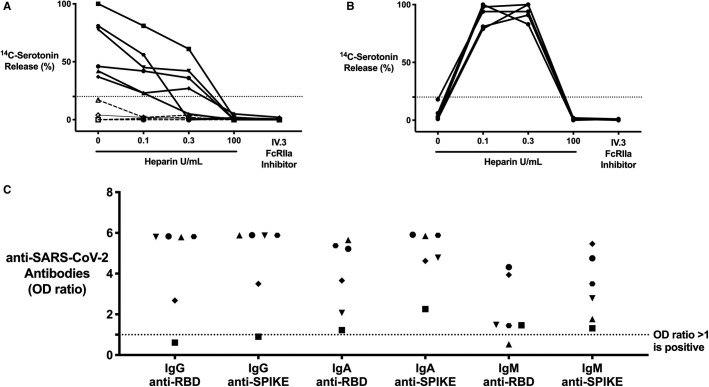

Blood samples were referred to the MPIL for HIT testing from 10 critically ill COVID‐19 patients (Table 1 ). All patients developed thrombocytopenia and had been exposed to heparin. Four patients developed thrombosis, one did not, and data were unavailable for the remaining five. Initial testing for IgG, IgA, and IgM anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies was negative in five samples (OD405 nm < 0.4), thus excluding HIT (Table 2 ). IgG‐specific anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies were then tested in the five positive samples; two were negative (OD405 nm < 0.45), and three were weakly positive (OD405 nm range 0.495–0.931). Of these weakly positive samples, the positive predictive value of HIT is <1.4% and thus makes a diagnosis of HIT unlikely (Table 2).16 All 10 critically ill COVID‐19 samples were then tested in the SRA where none demonstrated heparin‐dependent platelet activation (Figure 1A ). This combination of anti‐PF4/heparin EIA results with heparin‐independent platelet activation excludes HIT in all samples.13

TABLE 1.

Critically ill COVID‐19 patient characteristics

| Sample ID | Sex | Age | Heparin use | Platelet nadir (106/L) | Thrombosis | ICU admission | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | M | 58 | UFH | 69 000 | Present | Yes | Discharged |

| 2 | M | 64 | LMWH | 52 000 | — | Yes | Deceased |

| 3 | M | 49 | UFH | — | — | Yes | — |

| 4 | M | 53 | UFH | 58 000 | Present | Yes | Deceased |

| 5 | M | 65 | UFH | 12 000 | — | Yes | Deceased |

| 6a | M | 80 | UFH | 96 000 | — | Yes | Deceased |

| 7a | M | 51 | UFH | 61 000 | Present | Yes | Deceased |

| 8a | M | 70 | UFH | 42 000 | Present | Yes | Discharged |

| 9a | F | 77 | UFH | 11 000 | — | Yes | — |

| 10a | F | 71 | UFH | 72 000 | Absent | Nob | Deceased |

Abbreviations: LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; SRA, serotonin release assay; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Platelet‐activating in the SRA.

Palliative goals of care.

TABLE 2.

Anti‐PF4/heparin IgG, IgA, and IgM antibody levels in COVID‐19 samples detected by EIA

| Sample ID (COVID−19) | IgG, IgA, IgM (OD405 nm)a | IgG‐specific (OD405 nm)b | Positive predictive value of HIT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.506 | 0.235 | <0.5 |

| 2 | 0.102 | — | — |

| 3 | 0.867 | 0.495 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 0.168 | — | — |

| 5 | 3.155 | 0.583 | 1.4 |

| 6 | 0.456 | 0.103 | <0.5 |

| 7 | 1.64 | 0.931 | 1.4 |

| 8 | 0.086 | — | — |

| 9 | 0.261 | — | — |

| 10 | 0.049 | — | — |

Note

Samples that were initially positive in the IgG, IgA, IgM anti‐PF4/heparin EIA (bold) were subsequently tested in the IgG‐specific anti‐PF4/heparin EIA. The positive predictive value of HIT is based on the IgG‐specific anti‐PF4/heparin EIA result as previously described.

Abbreviations: EIA, enzymatic immunoassay; HIT, heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia; PF4, platelet‐factor 4.

Positive OD405 nm >0.4 in the IgG, IgA, IgM anti‐PF4/heparin EIA.

Positive OD405 nm >0.45 in the IgG‐specific anti‐PF4/heparin EIA.

FIGURE 1.

Critically ill coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) patients with COVID‐19 antibodies contain immune complex (ICs) that are capable of platelet activation in the serotonin release assay (SRA) in a manner that is unique from heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) ICs. (A) COVID‐19 (n = 10) patient sera compared to (B) HIT patient (n = 5) sera, serving as a control, in the SRA. 14C‐serotonin release was measured in the absence or presence of increasing heparin doses or with addition of IV.3 (FcγRIIA inhibitor); 14C‐serotonin release >20% is positive in the SRA (horizontal dashed line). Most COVID‐19 patient sera (n = 6, solid line) demonstrate heparin‐independent platelet activation, as opposed to classic HIT controls. Platelet activation was inhibited with IV.3 in both groups. C, IgG, IgA, and IgM COVID‐19 antibodies in critically ill COVID‐19 patient sera (platelet‐activating, n = 6). Antibodies were measured in the SARS‐CoV‐2 ELISA and include RBD and spike protein specificity. Each symbol represents the same distinct patient result. Values are shown as a ratio of observed optical density to the determined assay cut‐off optical density. Values above 1 are considered positive in the SARS‐CoV‐2 ELISA

Of note, six critically ill COVID‐19 samples demonstrated significant platelet activation in the absence of heparin (Figure 1A). Platelet activation was inhibited with all heparin concentrations (0.1, 0.3 U, and 100 U/ml), as opposed to the classic, heparin‐dependent activation seen in HIT patients (Figure 1A,B). Addition of IV.3 (FcγRIIA inhibitor) inhibited platelet activation, confirming an IgG‐specific IC‐mediated reaction (Figure 1A,B). Because certain virus‐specific antibodies are known to form ICs, we tested for COVID‐19 antibodies using our anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2‐ELISA.14 This ELISA is highly sensitive and specific for antibodies against the COVID‐19 spike glycoprotein (spike) and RBD located within the spike protein. All six platelet‐activating samples contained IgG‐specific antibodies against RBD, spike, or both proteins (Figure 1C), while none of the controls had anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies. Convalescent plasma from non‐critically ill COVID‐19 subjects (n = 8) did not activate platelets in the SRA, despite having high titers of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies, indicating that antibodies alone are insufficient for platelet activation (data not shown). A subset of critically ill COVID‐19 patient sera thus contains ICs that mediate platelet activation via FcγRIIA signalling.

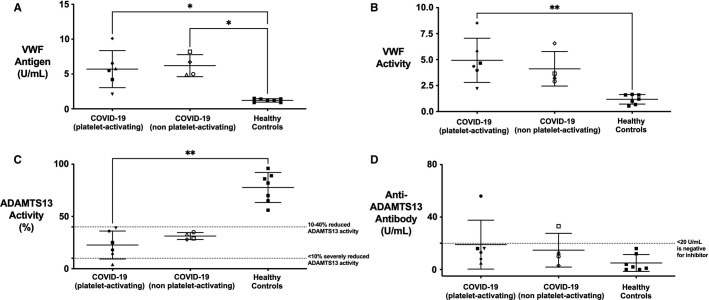

Immune complexes are known to trigger endothelial cell activation in diseases such as HIT and lupus vasculitis with subsequent VWF release.17., 18. Similarly, increased VWF release is a hallmark of COVID‐19 coagulopathy and has been correlated with mortality.19., 20. We therefore tested VWF antigen in our samples, and found markedly elevated levels (range 2.1–10.1 U/ml; mean = 5.9 U/ml; normal range 0.5–1.5 U/ml) compared to healthy controls (range 0.9–1.5 U/ml; mean = 1.2 U/ml; Figure 2A ). Ristocetin activity, as a marker of VWF activity, was also significantly increased (range 2.2–8.52 U/ml; mean 4.6 U/ml; normal range 0.8–1.8 U/ml) compared to healthy controls (range 0.53–1.67 U/ml, mean = 1.18 U/ml; Figure 2B). These increases were not significantly different between COVID‐19 patients with or without immune complexes. These data confirm elevated VWF in our samples, as has previously been shown.

FIGURE 2.

Critically ill coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) samples with platelet‐activating immune complex (ICs) show evidence of significant endothelial activation. A, von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen and (B) VWF activity are significantly elevated in critically ill COVID‐19 compared to healthy controls. These differences are not statistically different from COVID‐19 patients without platelet‐activating ICs. C, ADAMTS13 activity is moderately reduced (10%–40%) in COVID‐19 compared to healthy controls without an associated increase in (D) anti‐ADAMTS13 antibody. One COVID‐19 sample was positive for presence of an anti‐ADAMTS13 antibody, but this sample did not correspond to a severe reduction in ADAMTS13 activity. Therefore, none of the COVID‐19 samples meet criteria for TTP and are more in keeping with enhanced endothelial activation secondary to a secondary thrombotic microangiopathy. *p < .05, **p < .01, 2‐tailed, unpaired Student’s t‐test

To determine if this VWF increase was related to ADAMTS13 metalloproteinase function, we tested for ADAMTS13 activity and the presence of anti‐ADAMTS13 antibody. ADAMTS13 activity was moderately reduced (<40%) in all COVID‐19 samples but only severely deficient (<10%) in one (Figure 2C). Only one sample contained anti‐ADAMTS13 antibody, which did not correspond to severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (Figure 2D). The elevated VWF is therefore not secondary to severe ADAMTS13 reduction and also confirms that anti‐ADAMTS13 antibodies are not responsible for the platelet activation.

We have described our findings in critically ill COVID‐19 samples obtained from patients with a clinical suspicion for HIT. Similar to HIT, certain patient samples contain ICs capable of mediating platelet activation. However, in contrast to HIT, COVID‐19 ICs are not formed of anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies. The lack of anti‐PF4/heparin antibodies and presence of heparin‐independent SRA activation strongly rules out HIT. Furthermore, these platelet‐activating ICs are inhibited by FcγRIIA blockade and heparin, including therapeutic (0.1 and 0.3 U/ml) and high (100 U/ml) doses. Our findings are supported by previous work showing significantly increased platelet apoptosis, secondary to IgG‐mediated FcγRIIA signaling, in critically ill COVID‐19 patients.21 It is important to note that the platelet‐activating ICs in our cohort were identified using a buffer control (i.e., no addition of heparin). This step should thus be included in all SRA testing, as it can both identify atypical HIT and non‐HIT platelet‐activating ICs.22 Together, these observations highlight a novel mechanism for COVID‐19 ICs in severe illness.

We also confirm that this mechanism is separate from previously noted coagulopathic changes, namely involving the VWF‐‐ADAMTS13 axis.19 Prior studies have shown that VWF antigen levels and reduction of ADAMTS‐13 activity correlate with disease severity.23 These changes are also associated with increased mortality, likely secondary to microthrombotic complications. We demonstrate that our observations are not secondary to severe ADAMTS13 activity reduction (<10%) or the presence of anti‐ADAMTS13 antibody, as described in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). This pattern is more consistent with a secondary thrombotic microangiopathy and is likely compounded by the presence of platelet‐activating ICs.24., 25.

One limitation of this study is the inability to characterize the specificity of these platelet‐activating ICs. It is possible that the ICs are composed of COVID‐19 virus‐‐antibody complexes, similar to that seen with H1 N1 viral infection.26 This is further supported by inhibition with therapeutic heparin, as heparin binds the SARS‐CoV‐2 RBD to cause a conformational change with altered binding specificity, potentially disrupting the ICs and inhibiting platelet activation.27 In addition, access to clinical data was limited and so extrapolations cannot be made regarding association with thromboembolic phenomena or additional clinical factors. Regardless, the data presented here outline the characteristics of these ICs and differentiate them from other severe coagulation disorders, including HIT and TTP.

We thus propose a model whereby certain critically ill COVID‐19 patients feature a novel IC‐mediated thrombotic microangiopathy that is characterized by significant platelet activation. These ICs can produce a highly prothrombotic state resembling HIT but with unique platelet‐activating properties.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I. Nazy designed the research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. S.D. Jevtic, J.C. Moore, A. Huynh, and J.W. Smith carried out the described studies, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.G. Kelton and D.M. Arnold designed the research and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding support for this work was provided by a grant from the Ontario Research Fund (ORF #2426729), COVID‐19 Rapid Research Fund (V#C‐191‐2426729‐NAZY) and Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR)‐COVID‐19 Immunity Task Force (CITF) (#VR2‐173204) awarded to Dr. Ishac Nazy, and Academic Health Sciences Organization (HAHSO) grant awarded to Dr. Donald M. Arnold (#HAH‐21‐02).

COVID‐19 Rapid Research Fund#C‐191‐2426729‐NAZY

Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR)‐COVID‐19 Immunity Task Force (CITF)#VR2‐173204

Ontario Research Fund2426729

Academic Health Sciences OrganizationHAH‐21‐02

Footnotes

Manuscript handled by: Ton Lisman

Final decision: Ton Lisman, 01 February 2021

REFERENCES

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2019;2020(382):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F., et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nahum J., Morichau‐Beauchant T., Daviaud F., et al. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llitjos J.F., Leclerc M., Chochois C., et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID‐19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1743–1746. doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warkentin T.E., Kaatz S. COVID‐19 versus HIT hypercoagulability. Thromb Res. 2020;196:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong B.H., Fawaz I., Chesterman C.N., Berndt M.C. Heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia: mechanism of interaction of the heparin‐dependent antibody with platelets. Br J Haematol. 1989;73:235–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelton J.G., Sheridan D., Santos A., et al. Heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia: laboratory studies. Blood. 1988;72:925–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roncati L., Ligabue G., Fabbiani L., et al. Type 3 hypersensitivity in COVID‐19 vasculitis. Clin Immunol. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warrior S., Behrens E., Gezer S., Venugopal P., Jain S. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia in patients with COVID‐19. Blood. 2020;136:17–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-134702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horsewood P., Warkentin T.E., Hayward C.P., Kelton J.G. The epitope specificity of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:161–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheridan D., Carter C., Kelton J.G. A diagnostic test for heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 1986;67:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huynh A., Arnold D.M., Kelton J.G., et al. Development of a serological assay to identify SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies in COVID‐19 patients. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.09.11.20192690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studt J.D., Budde U., Schneppenheim R., et al. Quantification and facilitated comparison of von Willebrand factor multimer patterns by densitometry. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:567–574. doi: 10.1309/75CQ-V7UX-4QX8-WXE7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warkentin T.E., Sheppard J.I., Moore J.C., Sigouin C.S., Kelton J.G. Quantitative interpretation of optical density measurements using PF4‐dependent enzyme‐immunoassays. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1304–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blank M., Shoenfeld Y., Tavor S., et al. Anti‐platelet factor 4/heparin antibodies from patients with heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia provoke direct activation of microvascular endothelial cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:121–129. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun W., Jiao Y., Cui B., Gao X., Xia Y., Zhao Y. Immune complexes activate human endothelium involving the cell‐signaling HMGB1‐RAGE axis in the pathogenesis of lupus vasculitis. Lab Invest. 2013;93:626–638. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goshua G., Pine A.B., Meizlish M.L., et al. Endotheliopathy in COVID‐19‐associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single‐centre, cross‐sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e575–e582. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3026(20)30216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry B.M., Benoit S.W., de Oliveira M.H.S., Lippi G., Favaloro E.J., Benoit J.L. ADAMTS13 activity to von Willebrand factor antigen ratio predicts acute kidney injury in patients with COVID‐19: Evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 induced secondary thrombotic microangiopathy. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Althaus K., Marini I., Zlamal J., et al. Antibody‐induced procoagulant platelets in severe COVID‐19 infection. Blood. 2020;137:1061–1071. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warkentin T.E., Arnold D.M., Nazi I., Kelton J.G. The platelet serotonin‐release assay. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:564–572. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancini I., Baronciani L., Artoni A., et al. The ADAMTS13‐von Willebrand factor axis in COVID‐19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;19:513–521. doi: 10.1111/jth.15191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold D.M., Patriquin C.J., Nazy I. Thrombotic microangiopathies: a general approach to diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2017;189:E153–E159. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doevelaar A.A.N., Bachmann M., Hoelzer B., et al. COVID‐19 is associated with relative ADAMTS13 deficiency and VWF multimer formation resembling TTP. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.23.20177824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boilard E., Pare G., Rousseau M., et al. Influenza virus H1N1 activates platelets through FcgammaRIIA signaling and thrombin generation. Blood. 2014;123:2854–2863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y., Du Y., Kaltashov I.A. The utility of native MS for understanding the mechanism of action of repurposed therapeutics in COVID‐19: heparin as a disruptor of the SARS‐CoV‐2 interaction with its host cell receptor. Anal Chem. 2020;92:10930–10934. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]