Abstract

Background

COVID‐19 pandemic has impacted the way things are done in walks of life including nursing education in both developing and developed countries. Nursing schools all over the world as well as in developing countries responded to the pandemic following the guidelines of the World Health Organisation and different countries specific guidelines regarding the pandemic.

Aim

This reflective piece aims to describe the effect of COVID‐19 on nursing education in developing countries.

Result

Face‐to‐face teaching and learning were converted to virtual remote learning and clinical experiences suspended to protect the students from the pandemic. Specific but broader responses to the pandemic in the Caribbean and other developing countries have been shaped by financial, political and other contextual factors, especially the level of information technology infrastructure development, and the attendant inequities in access to such technology between the rural and urban areas. Internet accessibility, affordability and reliability in certain areas seem to negatively affect the delivery of nursing education during the COVID‐19 lockdown.

Conclusion and Implications for Nursing and/or Health Policy

The impact of COVID‐19 on nursing education in the Caribbean and other parts of the world has shown that if adequate measures are put in place by the way of disaster preparedness and preplanned mitigation strategies, future crises like COVID‐19 will have less impact on nursing education. Therefore, health policymakers and nursing regulatory bodies in the developing countries should put policies in place that will help in responding, coping and recovering quickly from future occurrences.

Keywords: COVID‐19, developing country, effect, Jamaica, nursing education

Background

COVID‐19 is a public health pandemic and a global crisis that affects every aspect of life, with potentially devastating social, economic and political implications (United Nations Development programme [UNDP] 2020). The pandemic has impacted all sectors, including nursing education. As the crises escalated, many governments closed schools, colleges and universities to ensure the safety of students, teachers and nations. With the onset of the pandemic, globally, face‐to‐face classes, clinical skills laboratories and the clinical placement of students were either suspended or restricted and more especially in countries that were critically affected by the outbreak in order to maintain and safeguard the health of students and faculty as a whole (British Columbia College of Nursing Professionals 2020; College & Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta 2020; Jackson et al. 2020).

The irresolute time span of the COVID‐19 pandemic and suspension of clinical teaching and experiences in the healthcare facilities have affected students’ readiness for the licensure examination. Final‐year students face uncertainties regarding completion of the programme and timelines for sitting their licensure examinations.

To be able to continue teaching and learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic, while complying with the COVID‐19 prevention protocols, many institutions of higher learning switched from the traditional face‐to‐face teaching and learning to the virtual mode. This approach was also adopted by schools of nursing in the Caribbean and other developing and developed countries. Content that was delivered in a combined face‐to‐face and online teaching and learning hybrid mode went fully online. Content that was previously taught only ‘face‐to‐face’ had to be quickly converted to online delivery, and teachers were trained to deliver ‘virtual classroom sessions’ when necessary. This solution, however, limited the skills development and clinical practice placement of students, which is the normal approach in the traditional nursing curricula. Teachers were forced to learn how to navigate and deliver the course content online. Also, students’ families and guardians were forced to provide the needed technology and Internet services required to access the classes online.

Challenges and Attempts to Mitigate the Clinical Placement Crisis

Several teaching methods have been considered, such as the use of blended learning methodologies to enhance clinical skills, and to mitigate the limited clinical exposure; however, gaps have been identified in finding an effective method of attaining clinical skills competency with online teaching (McCutcheon et al. 2015). Video demonstrations to supplement the lack of clinical exposure are another consideration when appropriate equipment is available. However, if the resources are unobtainable, students would have to attain these skills in the future (Texas Board of Nursing 2020); consequently, there is a need for modifications of the nursing curricula to include heighten use of high‐fidelity simulation to aid students in the completion of their required clinical rotations (Redden 2020).

As clinical sites rebuffed the practical experiences for students (United States National Council of State Boards of Nursing 2020), integrating clinical skills and the development of required competences have become the greatest curricular challenges in nursing education. The United States National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has been reviewing the legislations, and the standards of best‐practice available to make recommendations to schools of nursing, on how to proceed. Among the solutions include, more utilization of high‐fidelity simulation was proposed; for example, the Board of Nursing in Iowa allowed substitution of clinical experiences (even exceeding the previously recommended 50%) with simulated experiences, and for students who were not graduating to provide more clinical experiences whenever they could be provided in the future (NCSBN 2020).

The shortage of nurses is another factor that could potentially threaten the clinical placement and supervision of students. In anticipation of an even greater shortage of healthcare professionals as a result of the pandemic, the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning and the Society for Simulation in Healthcare published a position statement on 30 March 2020, proposing that regulatory bodies and policy makers could be flexible in allowing substitution of clinical experiences with virtual simulations (INACSL & SSH 2020). This modality, which had been a complement to clinical teaching, is now being presented as a potential solution for substitution of clinical hours. However, the majority of schools in the developing countries, including our setting in Jamaica, might have never used high‐fidelity stimulation in teaching the clinical skills or just learnt how to use simulation (high) but do not have the necessary resources, both material and human resources.

Contextual Issues: when the Solutions do not ‘fit all’

In the Caribbean, several schools of nursing do not have the necessary resources to address the challenges of teaching fully online and implementing virtual simulations. In cases where the resources are present, they still have some limitations. Students may not have a device to access content. Even in cases where students have a device, they may not have access to Internet as most digital technologies uses Internet or data services to generate, store or process data. Assuming that ideally all students had Internet access and devices, if virtual simulations are utilized, the modality would be a totally new experience for both faculty and students and the virtual modules are not readily available at the schools. Therefore, support for students from universities and educators is necessary to cope with those unprecedented challenges (American Association of Colleges of Nursing 2020). Faculty members who have reviewed the simulations see their value based on the principles/concepts however, the cases were developed for a different market and it may be difficult to link them to the students’ real‐life experiences. Purchasing access to web‐based resources is expensive for students, and unfortunately, most schools do not have pre‐recorded procedures to rely on during periods of crises including a pandemic, and that causes university to use alternative methods of teaching. There are sometimes budgetary constraints at institutional level that places priorities in other items. These financial obstacles have been magnified by the pandemic; therefore, the challenge is even greater than in normal circumstances in trying urgently to subsidise virtual products to deliver the curriculum in developing countries, even at discounted prices. Although as the pandemic and lockdown progressed, many publishers in developed countries supported the countries with online resources. Nonetheless, getting stimulated skills and scenarios that may be suitable for each developing country’s context may be difficult, hence substitution with available resources, which may not be ideal for all the skills and scenarios.

Impact of COVID‐19 on Nursing Students

The movement of all programmes to the online platforms has created a new problem, inequality in access to learning. While students may use their mobile phones for access, the type and capacity of the device is a problem, due to insufficient memory space to download the platforms used for learning. The battery life of these devices is also a limitation (Honey 2017). Many students live in distant geographical areas with limited or no access to Internet, inadequate financial resources, do not own the required textbooks, depended heavily on campus libraries and do not own computers. In addition, there has been an interruption in the way students’ socialization takes place. Students that generally sit together to learn face to face on campus, meet with their lecturers and work in groups, had to quickly cope with challenges of attending classes virtually from home, and at the same time learn and adapt to different platforms such as Google Classroom, Blackboard Collaborate, Zoom and Moodle. This transition was inevitable and abrupt regardless of their demographics and learning styles, which are factors that are important to consider when transitioning from face to face to online interface; for example, studies have suggested that older students tend to have more difficulty navigating online platforms in comparison with their younger counterparts (McCutcheon et al. 2015).

The delivery of content online introduced innovative methods of assessments, and some anxiety in students for which virtual assessments are new. Literature has supported that the transition to online assessments can be done through tutorials and familiarizing students with this modality. This approach reduces the uncertainty and anxiety among students and creates ease in revising assessment methods (Beavis et al. 2012). Another issue brought about by the switch to online delivery and suspension of clinical teaching is the extension in the length of the programme. Initially, students had registered for a four‐year programme. In the current situation, it is estimated that the programme will be extended for at least an additional semester to facilitate the much‐needed clinical experience and the clinical hours required by the governing bodies (British Columbia College of Nursing Professionals 2020).

Impact on the Profession and the Healthcare System

Although there are several nursing schools in developing countries that have increased the number of nurses graduating each year, including in the Caribbean, the growth in the number is not comparable with the population growth, barely improving the ‘nurse‐to‐population density levels’ (WHO State of the World’s Nursing 2020, p.3). Globally, approximately 89% of nursing shortage is in the developing countries with 1 out of 8 nurses practising outside their country of birth or training (WHO State of the World’s Nursing 2020, p.3). The shortage is coupled with continued migration of nurses to developed countries where they receive better incentives, financial benefits, perceived opportunity for improved quality of life, career advancement and/or education (Drennan & Ross 2019). The phenomenon of migration and nursing shortage will continue to affect developing countries and the Caribbean in particular. The profession faces a dilemma of accepting newly graduate nurses who have been trained in different circumstances. The possibility of a reduction in the number of persons interested in pursuing the career of nursing due to financial constraints and not being able to find institutions, which would hire them due financial aftermath of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The sudden disruption in health service delivery and student nurses completing training has forced premature completion of training for nursing students in some states. This relaxation of requirement aims at injecting more nursing staff to assist with the increased demand on the already stretched healthcare system (Jividen 2020). While grateful for the availability of more nurses to mitigate the situation, this measure poses a risk for lack of confidence in the healthcare system, and fear of being treated by nurses who are not adequately trained (American Association of Colleges of Nursing 2020). On the other hand, inflexibility and not allowing final‐year students to complete in the present circumstances, translates in at least 14 000 nursing students not completing the programme within the stipulated time frame, hence preventing an increase nursing staff complement (Jividen 2020). In developing countries, not allowing final‐year students to complete within reasonable time could have devastating consequences for the workforce. Just the addition of extra semester(s), will for the first time in history create a gap, which in the face of a pandemic, could have serious implications for health systems.

The Way forward

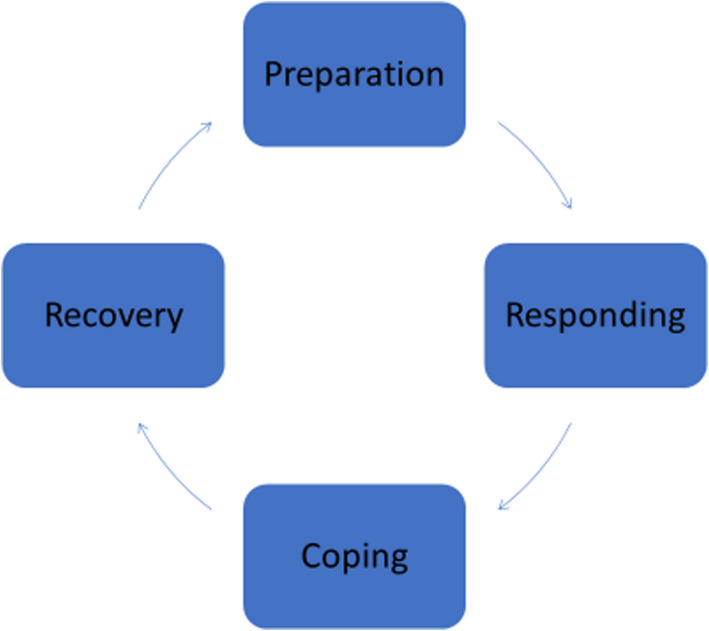

Every nursing educational institution is required prepare, respond and recover as soon as possible (UNDP 2020). According to the task force on COVID‐19, in looking ahead, a cyclical approach to educational emergencies should be embraced: prepare, cope and recover (Azzi‐Huck & Shmis 2020). Combining both approaches, in going forward nursing education in Jamaica, the Caribbean region and other developing countries should consider and embrace all the strategies that are needed in cases of emergencies, because COVID‐19 is just one pandemic, other emergencies could happen, they are inevitable, and the only solution is to prepare, respond, cope and recover as quickly as possible (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

(1) Cycle of Recovery: Way forward. Adapted from Managing the impact of COVID‐19 on education systems around the world: How countries are preparing, coping, and planning for recovery by K. Azzi‐Huck, & T. Shmis, Copyright (2000), World Bank Group. (2) COVID‐19 pandemic—Humanity needs leadership and solidarity to defeat the coronavirus by UNDP (2020).

Preparation

COVID‐19 has been a major global emergency, which has affected almost all the countries in the world. Since the last global pandemic took place 10 decades ago, health systems had prepared to face major epidemics, but this novel coronavirus caught the world off guard. The crisis has revealed major gaps and challenges. Nursing schools need to be prepared for future emergencies by preparing video recording of procedures, for example using mannequins and standardized patients. This is imperative while waiting for the financial means and further modernization of their facilities and infrastructure for implementing simulation teaching. In going forward, all school should have contingency plans for abnormal situations such as this pandemic. The need for modernization of facilities and teaching platforms and modalities is paramount.

Responding

The global response to the pandemic is for every nursing educational institution to invest in the future (UNDP 2020). Many schools responded quickly initially by suspending face‐to‐face classes to prevent and reduce community spread. This was followed by the conversion from face‐to‐face teaching to online/virtual delivery of the theoretical aspect of the curriculum. This process was swift and commendable and must be sustained even after the crisis dissipates and things return to normal because it ensures the continuity of the teaching and learning. However, the clinical practicum aspect of learning experience suffered during this period as many schools do not currently have all the necessary resources and infrastructure for online simulation of the clinicals in place and may delay the graduation of students at the stated period. Therefore, it is important to have a full immersion of simulation into the nursing programme going forward to mitigate the effect of similar future occurrences in clinical practicum aspect of the curriculum. The suggestion of integrating more simulation experiences in the curriculum requires among many other factors that schools have the facilities, equipment, material and human resources to run these types of simulations. It is therefore not an easy solution to compensate for the current deficit in clinical practicum experiences. Virtual simulations, on the other hand, are Web‐based products and relatively easy to implement. They are considered expensive in developing countries, but in times of crisis it has become the practical solution while teachers and instructors prepare to develop their own indigenous videos and other virtual learning materials with the available infrastructures in their settings including mobile phone technology until students can return to skill laboratories and healthcare facilities. Returning to the clinical areas with modified protocols would also be possible if resources are available. For example, budgetary allocation to supply personal protective equipment (PPE) for students and teachers for every patient encounter, without causing added burden to the healthcare system.

Coping

If adequate measures were put in place to mitigate the effects of the crisis even before it occurs, it will expedite coping once the crisis strikes and decrease its undesirable consequences (Azzi‐Huck & Shmis 2020). Coping during and after the crisis should not only be limited to the process of teaching and learning, the students and teachers’ emotional well‐being should be considered as this may affect the process and outcome of teaching and learning. An individual's response to this crisis may differ including intense fear, helplessness (Pace university n.d) and even mental breakdown. These experiences may be traumatic and require professional assistance to cope (Pace university n.d). Therefore, measures such as counselling and mental health sessions should be developed for both staff and students, which will help to minimize and allay their anxiety and fear. Additionally, individuals can be referred as the need arise. This will help students and educators to cope as schools prepare to start again face‐to‐face teaching and learning and return to the new normal in the clinical areas.

Recovery

As the pandemic is controlled, nursing training institutions moves into ‘recovery’ mode, with institutions and governing bodies implementing policies and measures to regain lost hours and experiences (Azzi‐Huck & Shmis 2020). It is imperative that nursing needs flexible education systems that will be able to withstand or recover quickly from crisis and other unforeseeable circumstances. Back‐up plans should be put in place in case of future uncertainties. A modernization of the programmes to include more online and virtual options could help in smooth transition if the needs arise again. Revision of regulations related to nursing curricula by the various nursing governing bodies are necessary, to accommodate and facilitate credible alternative teaching and learning options. Timely and effective responses in crises should be taken into consideration.

Conclusion/Implications for Nursing & Health Policy

There is uncertainty regarding the end of the COVID‐19 pandemic and the possibility of new strains of the virus emerging. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic in nursing education in developing countries may be greater than in developed countries due to disparities. Online learning has become the solution to complete the curriculum; however, it does not address the clinical practicum component. Virtual simulations and high‐fidelity simulation equipment are not ubiquitous in developing countries as there are challenges related to access and cost. The return of students to the clinical area may be challenging in terms of staff supervision and safety. The cost that represents providing students and teachers with personal protective equipment for every clinical practicum encounter may be a challenge. Therefore, multi‐sectorial intervention should be put in place by the joint effort of government, healthcare institutions, universities and nursing regulatory bodies to be in preparation mode at all times to respond to any future emergencies. Policies regarding the mandatory substitution of a certain percentage of clinical experience with simulation (high, medium, low) should be put in place especially in developing countries by the regulatory bodies. This should include but not limited to the use of what each individual schools and countries have in place to meet their local demand while waiting for changes in advanced technology as well as inclusion of high‐fidelity simulation, which will help them to cope, adapt and recover as quickly as possible in times of crisis.

Author Contributions

Study conception: ACF

Study Design: ACF, JS, NMS

Manuscript writing: ACF, JS, NMS, TR

Approval of the final draft: ACF, JS, NMS, TR

Critical revisions for important intellectual content: ACF, TR

Ethics approval/consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Agu C.F., Stewart J., McFarlane‐Stewart N.& Rae T.. (2021) COVID‐19 pandemic effects on nursing education: looking through the lens of a developing country. Int. Nurs. Rev. 68, 153–158

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

References

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing . (2020). AACN's Foundation for Academic Nursing Supports Students Impacted by COVID‐19 in All 50 States. News 12 May. Available at: https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/aacn‐s‐foundation‐for‐academic‐nursing‐supports‐students‐impacted‐by‐covid‐19‐in‐all‐50‐states/?article_id=731470 (accessed May 20 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Azzi‐Huck, K. & Shmis, T. (2020). Managing the impact of COVID‐19 on education systems around the world: How countries are preparing, coping, and planning for recovery. Blog March 18. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/managing‐impact‐covid‐19‐education‐systems‐around‐world‐how‐countries‐are‐preparing (accessed April 19 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Beavis, J. , Morgan, J. & Pickering, J. (2012) Testing nursing staff competencies using an online education module. Renal Society of Australasia Journal, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia College of Nursing professionals . (2020). Effect of COVID‐19 pandemic on nursing education programs, faculty and students. Announcement 17 March. Available at: https://www.bccnp.ca/bccnp/Announcements/Pages/Announcement.aspx?AnnouncementID=139 (accessed 31 April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta . (2020). Guiding Principles: Effect of COVID‐19 pandemic on nursing education programs, faculty members and students. News 2 April. Available at https://nurses.ab.ca/about/what‐is‐carna/news/2020/04/02/guiding‐principles‐effect‐of‐covid‐19‐pandemic‐on‐nursing‐education‐programs‐faculty‐members‐and‐students (accessed May 1 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Drennan, V.M. & Ross, F. (2019) Global nurse shortages‐the facts, the impact and action for change. British Medical Bulletin, 130 (1), 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey, M. (2017) Undergraduate Student Nurses' Use of Information and Communication Technology in their Education. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 250, 37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INACSL & SSH . (2020). Use of Virtual Simulation during the Pandemic. Position Statement 30 March. Available at: https://www.ssih.org/COVID‐19‐Updates/ID/2237/COVID19‐SSHINACSL‐Position‐Statement‐on‐Use‐of‐Virtual‐Simulation‐during‐the‐Pandemic (accessed April 15 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. , et al. (2020) Life in the pandemic: Some reflections on nursing in the context of COVID‐19. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29, 2041–2043 10.1111/jocn.15257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jividen, S. (2020). How Nursing Students Are Rising Up To Fight COVID‐19. Blog 20 April. Available at: https://nurse.org/articles/nursing‐students‐fighting‐covid‐19/ (accessed April 29 2020). [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon, K. , Lohan, M. , Traynor, M. & Martin, D. (2015) A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face‐to‐face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71 (2), 255–270. 10.1111/jan.12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2020) Changes in Education Requirements for Nursing Programs During COVID‐1. Available at: https://www.ncsbn.org/Education‐Requirement‐Changes_COVID‐19.pdf accessed April 12 2020 . [Google Scholar]

- Pace University (n.d). Coping after a Crisis. Available at: https://www.pace.edu/counseling/resources‐and‐grants/self‐help‐resources/coping‐after‐a‐crisis (accessed April 10 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Redden, E. (2020) Health‐Care Students on the Front Lines. News 5 March. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/03/05/students‐studying‐be‐health‐care‐professionals‐front‐lines‐coronavirus‐outbreak (accessed April 12 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Texas Board of Nursing Bulleting (2020) Managing Clinical Experience During the COVID 19 Pandemic. Available at: http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=6&sid=b8932a77‐2cf7‐4a6f‐8ff7‐70fc13fe7b52%40pdc‐v‐sessmgr05 (accessed 20 April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme, Jamaica (2020) COVID‐19 Pandemic Humanity needs leadership and solidarity to defeat COVID‐19. Available at: https://www.jm.undp.org/content/jamaica/en/home/coronavirus.html accessed 13 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020) State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education. Jobs and Leadership. WHO, Geneva. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 (accessed 10 November 2020). [Google Scholar]