Summary

Available data on clinical presentation and mortality of coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) in heart transplant (HT) recipients remain limited. We report a case series of laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 in 39 HT recipients from 3 French heart transplant centres (mean age 54.4 ± 14.8 years; 66.7% males). Hospital admission was required for 35 (89.7%) cases including 14/39 (35.9%) cases being admitted in intensive care unit. Immunosuppressive medications were reduced or discontinued in 74.4% of the patients. After a median follow‐up of 54 (19–80) days, death and death or need for mechanical ventilation occurred in 25.6% and 33.3% of patients, respectively. Elevated C‐reactive protein and lung involvement ≥50% on chest computed tomography (CT) at admission were associated with an increased risk of death or need for mechanical ventilation. Mortality rate from March to June in the entire 3‐centre HT recipient cohort was 56% higher in 2020 compared to the time‐matched 2019 cohort (2% vs. 1.28%, P = 0.15). In a meta‐analysis including 4 studies, pre‐existing diabetes mellitus (OR 3.60, 95% CI 1.43–9.06, I 2 = 0%, P = 0.006) and chronic kidney disease stage III or higher (OR 3.79, 95% CI 1.39–10.31, I 2 = 0%, P = 0.009) were associated with increased mortality. These findings highlight the aggressive clinical course of COVID‐19 in HT recipients.

Keywords: COVID‐19, heart transplant, immunosuppressive medication

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) disease (COVID‐19) emerged in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has been spreading worldwide ever since into a global pandemic. As of the end of October 2020, nearly 50 million people were infected, worldwide, with approximately 1.2 million deaths [1]. COVID‐19 has a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic infection to mild upper respiratory tract illness, acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute cardiac injury [2, 3, 4, 5]. Although the risk of viral infection is markedly increased among solid organ transplant recipients, including heart transplant (HT) recipients, available data on clinical presentation and outcomes of COVID‐19 in this high‐risk population remain limited [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. In addition to chronic immunosuppression‐related risk, HT recipients commonly present with cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors, which have been associated with more frequent COVID‐19 infection and with worse outcomes [13, 14, 15]. The purpose of our study was to describe the clinical characteristics, outcomes and treatment management of laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 HT recipients from 3 heart transplant centres located in Ile‐de‐France area, the most populated region in France with 12.2 million inhabitants and ranking first in total number of COVID‐19 cases. To evaluate the relative increase in mortality in HT recipients during COVID‐19, we compared the mortality rate in the entire HT recipient cohorts of the three centres from March to June 2019 to the one from March to June 2020. Furthermore, we performed a systematic review and meta‐analysis of published studies reporting COVID‐19 outcomes in HT recipients to identify factors associated with death.

Methods

Study population

We performed a prospective case series study according to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (Table S1). All adult HT recipients (≥18 years old) from 3 heart transplant centres located in Ile‐de‐France (Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital, Henri Mondor Hospital and Bichat‐Claude Bernard Hospital) with laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 infection from 6 March to 29 June 2020 were included. Such patients have long been instructed to actively consult or report to their respective centre in case of acute dyspnoea or new onset of fever. Furthermore, with the beginning of the pandemic in France, a systematic review of COVID‐19 infection was prospectively performed in each centre. Diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was performed either by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs or through serology testing. Data collection included baseline characteristics, clinical presentation and radiologic findings in all patients as well as laboratory data in hospitalized patients. Follow‐up was performed through clinical evaluation or by phone interview. Management of immunosuppressive therapy was left at the discretion of local transplant physicians, in accordance with local practice and the practical guide of the French Society of Transplantation published early April 2020 (Table S2).

Outcomes

The end point of interest was the occurrence of death or mechanical ventilation. Risk factors for these adverse outcomes were determined from baseline characteristics and initial presentation. Furthermore, the relative increase in mortality during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic was assessed in the entire cohort of HT recipients followed in the three centres by comparing the mortality rates from March to June 2020 and from March to June 2019. The mortality rates among the entire HT recipients cohort of the three centres during the time periods of interest were provided by the Agence de Biomedecine, a governmental agency that prospectively collects data on all transplant recipients in France along with their outcomes.

Meta‐analysis of observational studies

To further improve the description of the mortality and morbidity associated with COVID‐19 in HT recipients, we performed a systematic review through PubMed and Embase databases of observational studies reporting outcomes following COVID‐19 in HT recipients. The estimate of incidence of death was provided by pooling study‐level data of all the studies as one population. We performed a meta‐analysis including the studies comprising of at least 10 patients and providing clinical description of fatalities cases following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis) guidelines to determine potential risk factors for death in COVID‐19 HT recipients (Table S3). A full electronic search was conducted in PUBMED and Embase, and the terms used for research were “COVID‐19”, “SARS‐CoV‐2”, “Heart transplant recipient”, “solid organ recipient”, up to December 2020. Citations were screened at the title and the abstract level and retrieved if considered relevant. The main inclusion criterion was an observational study reporting baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes in HT recipients with confirmed COVID‐19, without any restriction on follow‐up. Single case reports and small case series (n < 10 patients) were excluded from the meta‐analysis. End point of interest was death from any cause. Data were extracted using a standardized form by two investigators (C.G. and P.G.), and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The following relevant data were collected: first author, year of publication, total sample size, baseline characteristics such as age, time from transplantation, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV), chronic kidney disease, immunosuppressive treatments, need for hospitalization and death.

Statistics

Categorical variables were described as number (%), and continuous variables were described with mean ± standard deviation or median (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher's exact test or chi‐square test, and continuous variables were compared using Student's t‐test. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test. With the increased statistical power provided by the meta‐analysis, we evaluated potential risk factors for mortality following COVID‐19 in HT recipient. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval [CI] were determined using Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect models according to DerSimonian and Laird. Heterogeneity among trials for each outcome was estimated with chi‐square tests and quantified with I 2 statistics (with I 2 < 50%, 50–75% and >75% indicating low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively). Publication bias was estimated via visual inspection of the funnel plot of the effect estimates of variables tested in the meta‐analysis from the four studies against study size and precision.

Analyses were conducted using graphpad prism v8.4.3 (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) and the Cochrane's Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Clinical presentation, diagnosis and management

A total of 39 HT recipients were included, with confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with RT‐PCR in 37/39 (94.9%) cases. COVID‐19 was confirmed with serology in 2/39 (5.1%) cases, including one patient presenting with repeated negative RT‐PCR tests despite clinical and radiological profile highly suggestive with COVID‐19 and another patient, asymptomatic but exposed to the disease. Among COVID‐19 cases confirmed with RT‐PCR, several tests were performed on 19/37 (51.3%) patients, with a median of 2 (2–3.3) tests per patient and 15.5 [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27] days between the first and last PCR test (Fig. S1). Patient demographics, primary diagnosis, comorbidities and therapies are detailed in Table 1. The most frequently encountered clinical presentation were respiratory tract symptoms together with fever and dyspnoea (Table 2). A chest CT imaging was performed in 33/39 (84.6%) patients, without any case of reported pulmonary embolism. A total of 35/39 (89.7%) patients were hospitalized, including 14/39 (35.9%) patients in intensive care unit, while 4/39 (10.3%) were managed as outpatients. Median duration of hospitalization was 14 (8.5–27.5) days. Oxygen supplementation was required in 18 patients. Reduction of patients' baseline immunosuppressive therapy was performed in 29/39 (74.4%) cases. Conversely, corticosteroid therapy was maintained. A total of 21/39 (53.8%) patients were managed with antibiotics, while 6/39 (15.4%) and 1/39 (2.6%) received hydroxycholoquine and lopinavir–ritonavir, respectively. There was no use of remdesivir or convalescent plasma in the cohort.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Age, years | 54.4 ± 14.8 |

| Male sex | 26/39 (66.7%) |

| Underlying cardiomyopathy prior to transplant | Ischaemic cardiomyopathy: 11/39 (28.2%) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy: 18/39 (46.2%) | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: 4/39 (10.2%) | |

| Valvular cardiomyopathy: 3/39 (7.7%) | |

| Other: 3/39 (7.7%) | |

| Blood type | O: 15/39 (38.5%) |

| A: 15/39 (38.5%) | |

| B: 8/39 (20.5%) | |

| AB: 1/39 (2.5%) | |

| Time from transplantation, years | 4.9 (1.8–7.7) |

| Prior acute rejection | 25/39 (64.1%) |

| ISHLT cardiac allograft vasculopathy 2 or 3 | 9/39 (23.1%) |

| Serology status | |

| CMV‐positive | 26/38 (68.4%) |

| EBV‐positive | 35/37 (94.6%) |

| Baseline echocardiographic evaluation | |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 64.0 (60.0–68.0) |

| LV end‐diastolic diameter, mm | 48.0 (44–51.0) |

| Kidney function | |

| Creatinine, µmol/l | 126 (98.0–163.5) |

| Chronic kidney disease stage III or higher | 21/39 (53.8%) |

| On dialysis | 6/39 (15.4%) |

| Prior cardiac arrhythmia | 4/39 (10.3%) |

| Inflammatory disease | 5/39 (12.8%) |

| Prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack | 6/39 (15.4%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2/39 (5.1%) |

| Active smoking | 2/39 (5.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16/39 (40.0%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 12/39 (30.8%) |

| Hypertension | 28/39 (71.8%) |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease | 4/39 (10.3%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.0 ± 5.5 |

| Baseline medication | |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | 30/39 (76.9.5%) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 5/39 (12.8%) |

| Statin | 30/39 (76.9%) |

| Beta‐blocker | 26/39 (66.7%) |

| ACE‐I or ARBs | 16/39 (41.0%) |

| MRA | 1/39 (2.6%) |

| Oral anticoagulant | 3/39 (7.7%) |

| Insulin | 10/39 (25.6%) |

| Oral antidiabetic agent | 3/39 (7.7%) |

| Prednisone | 37/39 (94.9%) |

| Prednisone dosage >10 mg per day | 7/37 (18.9%) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 28/39 (71.8%) |

| Tacrolimus | 16/39 (41.0%) |

| Cyclosporine | 22/39 (56.4%) |

| Everolimus | 11/39 (28.2%) |

| Azathioprine | 4/39 (10.3%) |

ACE‐I, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin receptor blockers; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein Barr virus; LV, left ventricular; ISHLT: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Variables are provided as mean ± standard deviation or median (IQR).

Table 2.

Patient presentation, management and outcomes.

| Clinical symptoms prior to admission | |

| Fever | 21/39 (53.8%) |

| Dyspnoea | 18/39 (46.2%) |

| Respiratory tract symptoms (cough, expectoration, nasal congestion) | 21/39 (53.8%) |

| Myalgia | 5/39 (12.8%) |

| Anosmia | 2/39 (5.1%) |

| Ageusia | 5/39 (12.8%) |

| Headache | 2/39 (5.1%) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhoea, vomiting) | 13/39 (33.3%) |

| Chest CT performed | 33/39 (84.6%) |

| Delay between symptoms onset and CT, day | 6.0 (3.0–13.0) |

| Lung bilateral involvement | 25/33 (75.8%) |

| Lung overall involvement | |

| ≤10% | 14/33 (42.4%) |

| Between 10% and 50% | 8/33 (24.2%) |

| ≥50% | 11/33 (33.3%) |

| Admission for COVID‐19 | 34/39 (87.2%) |

| Admission in intensive care unit | 14/39 (35.9%) |

| Delay between symptom onset and hospital admission, days | 5.0 (2.0–10.0) |

| Covid‐related modification of immunosuppressive therapy | 29/39 (74.4%) |

| Transient withdrawal or reduction of | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 22/29 (76%) |

| Tacrolimus | 4/17 (23.5%) |

| Cyclosporine | 1/22 (4.5%) |

| Everolimus | 4/11 (36%) |

| Azathioprine | 2/4 (50%) |

| Biological characteristics | |

| Creatinine, µmol/l (n = 38) | |

| On admission | 150.5 (107.3–307.8) |

| Peak | 221.5 (108.8–438.8) |

| NT‐proBNP, ng/l | |

| On admission (n = 26) | 955.0 (320.0–4079) |

| Peak (n = 29) | 2257.0 (638.0–7620.0) |

| White blood cells count, 109/l (n = 36) | |

| On admission | 5.8 (4.2–8.4) |

| Peak | 8.9 (5.7–13.3) |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/l (n = 36) | |

| On admission | 0.65 (0.40–0.91) |

| Nadir | 0.48 (0.28–0.72) |

| Haemoglobin, g/dl | |

| On admission (n = 37) | 11.6 ± 2.0 |

| Nadir (n = 24) | 9.4 ± 2.6 |

| C‐Reactive protein, mg/l (n = 36) | |

| On admission | 43.8 (20.2–87.3) |

| Peak | 100.2 (34.8–217.8) |

| Procalcitonin, µg/l (n = 27) | |

| On admission | 0.48 (0.08–0.86) |

| Peak | 0.69 (0.12–1.50) |

| Fibrinogen, g/l | |

| On admission (n = 25) | 4.9 (3.7–6.4) |

| Peak (n = 27) | 6.1 (5.2–7.9) |

| D‐Dimer, ng/ml (n = 38) | |

| On admission (n = 13) | 1357.0 (1001.0–2550.0) |

| Peak (n = 21) | 2000.0 (980.5–5301.0) |

| Troponin peak | |

| High sensitivity, ng/l (n = 21/27) | 44.2 (17.5–75.0) |

| Nonhigh sensitivity, µg/l (n = 11/13) | 0.03 (0.01–0.09) |

| In‐hospital outcomes | |

| Need for noninvasive ventilation | 7/39 (17.9%) |

| Duration of noninvasive ventilation, day | 4.0 ± 2.7 |

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 8/39 (20.5%) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | 17.6 ± 15.2 |

| Acute kidney injury | 22/39 (56.4%) |

| Dialysis in patient not previously on dialysis programme | 6/35 (17.1%) |

| Death | 10/39 (25.6%) |

| Death or mechanical ventilation | 13/39 (33.3%) |

COVID 19, coronavirus disease 2019; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B type natriuretic peptide; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Variables are provided as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile 25–75%).

Cardiac manifestations

There was no reported case of new onset of cardiac arrythmia among hospitalized patients. Of the 32 patients with whom cardiac troponin was measured, a total of 23 presented with some degree of myocardial injury, with a troponin peak above the 99th percentile. Cardiac echocardiography was performed in 16 patients and reported a new onset of moderate alteration of left ventricle ejection fraction (i.e. 40–45%) in three cases, all of whom were later treated with mechanical ventilation and two of whom eventually died.

Outcomes

The median duration of follow‐up was 54 (19–80) days during which death and death or need for mechanical ventilation occurred in 10/39 (25.6%) and 13/39 (33.3%) patients, respectively. C‐reactive protein at admission and lung involvement ≥50% on chest CT were associated with occurrence of death or need for mechanical ventilation (Table 3). There were 17/39 (43.6%) cases of acute kidney injury and 6/39 (15.4%) patients required new onset of renal replacement therapy.

Table 3.

Markers of risk of death or need for mechanical ventilation.

| Variables |

Death or mechanical ventilation (n = 13) |

No death nor mechanical ventilation (n = 27) |

P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.8 ± 11.2 | 53.2 ± 16.7 | 0.97 |

| Male sex | 11 (84.6%) | 15 (55.6%) | 0.15 |

| Blood type O (vs. other blood types) | 4 (30.8%) | 10 (37.0%) | 0.73 |

| Blood type A (vs. other blood types) | 7 (53.8%) | 9 (33.3%) | 0.21 |

| Pretransplant ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 5 (38.5%) | 6 (22.2%) | 0.28 |

| Time post‐transplantation, years | 4.3 (1.4–8.8) | 5.0 (1.9–9.0) | 0.65 |

| History of acute rejection | 8 (61.5%) | 17 (63.0%) | 0.99 |

| History of ISHLT cardiac allograft vasculopathy 2 or 3 | 2 (15.4%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0.69 |

| Cytomegalovirus positive status | 10/12 (83.3%) | 16/26 (61.5%) | 0.28 |

| Epstein Barr Virus positive status | 12/12 (100.0%) | 23/25 (92%) | 0.99 |

| Chronic kidney disease stage III or higher | 9 (69.2%) | 12 (44.4%) | 0.31 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (53.8%) | 9 (33.3%) | 0.25 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 5 (38.5%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0.46 |

| Hypertension | 9 (69.2%) | 19 (70.3%) | 0.99 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.3 ± 4.3 | 27.3 ± 6.2 | 0.60 |

| Baseline medication | |||

| ACE‐I or ARB | 7 (53.8%) | 9 (33.3%) | 0.25 |

| Prednisone dosage >5 mg per day | 6 (46.2%) | 12 (44.4%) | 0.99 |

| Dual immunosuppressive therapy | 1 (7.7%) | 4 (14.8%) | 0.65 |

| CT lung involvement ≥50% | 8/12 (66.7%) | 3/21 (14.3%) | 0.006 |

| Laboratory variables at admission | |||

| Creatinine, µmol/l | 298.0 (149.0–522.0) | 137.0 (97.5–236.5) | 0.07 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/l | 75.5 (44.3–182.5) | 31.9 (3.0–62.6) | 0.01 |

| NT‐proBNP, ng/l | 895.0 (429.8–3555.0) | 1084.0 (433.5–5847.0) | 0.89 |

| White blood cell count, 109/l | 6.8 (4.8–11.3) | 5.7 (4.0–7.0) | 0.16 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/l | 0.53 (0.30–0.84) | 0.72 (0.43–1.02) | 0.23 |

| Procalcitonin, µg/l | 0.80 (0.33–1.00) | 0.11 (0.04–0.72) | 0.054 |

| Fibrinogen, g/l | 5.1 (3.4–7.8) | 4.9 (3.8–6.1) | 0.82 |

| D‐dimer, ng/ml | 1524.0 (1268.0–5308.0) | 1156 (340.0–2151.0) | 0.22 |

ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.

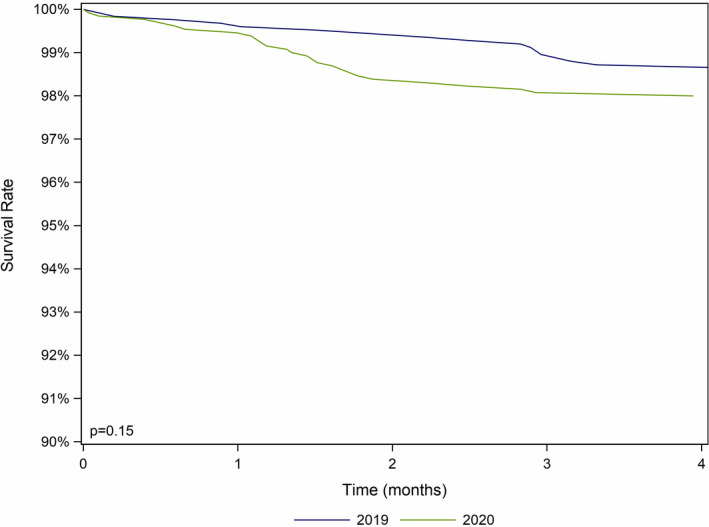

Among the 1248 HT recipients followed in the three participating centres on March 2019, 16 (1.28%) died by June 2019 whereas 26 of 1299 (2%) died from March to June 2020, although this 56% relative increase in mortality in 2020 was not statistically significant (P = 0.15). The 3‐month survival was 99% in 2019 compared to 98.1% in 2020 (P = 0.15; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Heart transplant recipient survival from March to June 2019 and March to June 2020.

Meta‐analysis

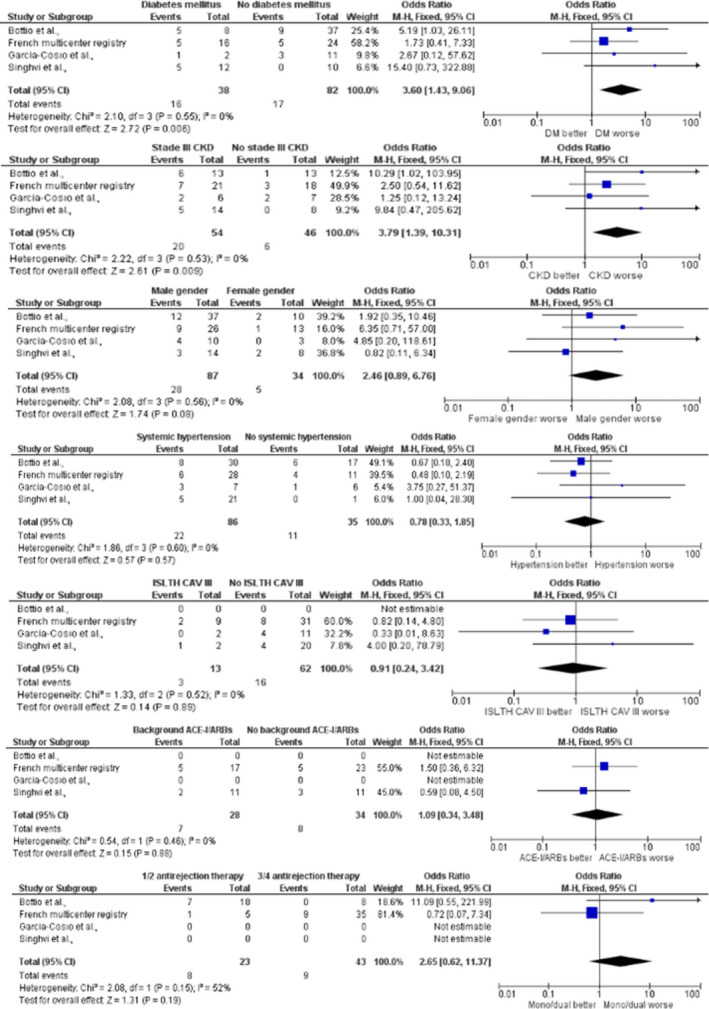

We screened 41 published studies [9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53] (Fig. S2 and Table S2) evaluating outcomes HT recipients with confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. When including the present case series, the overall reported proportion of death was 88/398 (22.1%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 18.3–26.4%). Overall, four studies, counting the present case series, were included in the meta‐analysis, comprising of 120 patients [18, 47, 52]. Factors associated with death were pre‐existing diabetes mellitus (OR 3.60, 95% CI 1.43–9.06, I 2 = 0%, P = 0.006) and chronic kidney disease stage III or higher (OR 3.79 95% CI 1.39–10.31, I 2 = 0%, P = 0.009; Fig. 2). Male gender, pre‐existing hypertension, severe cardiac allograft vasculopathy (ISHLT CAV 3), use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and single or dual immunosuppressive therapy (vs. triple or quadruple regimens) were not significantly associated with mortality. There was no evidence of publication bias (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Demographics and comorbidities according to occurrence of death in heart transplant recipients with COVID‐19. ACE‐I, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CAV, cardiac allograft vasculopathy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; DM, diabetes mellitus; ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; M‐H, Mantel‐Haenszel. For the impact of CKD and number of background immunosuppressive therapy, data presented for Bottio et al. [52], are from the study by Iacovoni et al. [17], which were eventually included in the study of Bottio et al.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that the observed rates of death and death or need for mechanical ventilation in laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 HT recipients were 25.6% and 33.3%, respectively. This finding is consistent with previous reports in heart and kidney transplant population. Thus, the clinical course of COVID‐19 is more aggressive in HT recipients than in the general population while the death rate among solid organ transplant recipients is higher with COVID‐19 than with other RNA respiratory viral infections such as influenza [54, 55]. However, as detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was not performed throughout the entire cohort, the death rate in our study may have overestimated the case fatality rate of COVID‐19. For this reason, we assessed the excess mortality because of COVID‐19 in the entire cohort of HT recipients followed in our three centres. By comparing the number of deaths from March to June 2020, and from March to June 2019, we observed an overall 56% excess mortality during the early outbreak of COVID, which corresponded to the number of COVID‐19‐attributed deaths, suggesting that the excess mortality was driven by COVID‐19‐related deaths and not by an increase in deaths from other causes.

HT recipients with COVID‐19 had similar initial clinical manifestations to the general population with fever, dyspnoea and respiratory symptoms even if these symptoms were less common [4, 17, 18, 54].

Another finding of our case series and meta‐analysis is that the initial disease severity and comorbidities are predictors of COVID‐19 outcomes. C‐reactive protein and lung involvement extent at hospital admission were identified to be associated with the occurrence of death or need for mechanical ventilation, while meta‐analysis showed that diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease stage III or higher were altogether increasing the risk of death. The link between pre‐existing comorbidities and more severe form of COVID‐19 has been consistently reported, although the specific pathophysiological mechanisms behind this association remain to be better defined. Diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease, in particular, have been reported in numerous studies and meta‐analyses as increasing mortality in the general population infected with COVID‐19 [56, 57]. Both comorbidities may be associated with dysfunction of the immune system and enhanced inflammation, which could partly explain the increased severity and mortality in COVID‐19 patients [58, 59]. Notably, hypertension which is the most common underlying comorbidity in HT recipients was not associated with death in the meta‐analysis. Although the reason for this specific result is not clear, it may be related to the remarkably high proportion of HT recipients with hypertension. Similarly, there was no relationship between renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) blocker use and death. A potential harmful effect of these agents has been speculated in the setting of COVID‐19 since it has been established that SARS‐CoV‐2 infects human cells through the binding of its Spike (S) protein to ACE2, acting as co‐receptor for cellular viral entry, while animal studies have suggested a potential up regulation of ACE2 expression by RAS blockers [60, 61]. No significant association of RAS blockers on COVID‐19‐related mortality was present in our study focusing on HT recipients, which is consistent with some other reports in the general population [62]. Randomized trials such as the ACE inhibitors or ARBs Discontinuation in Context of SARS‐CoV‐2 Pandemic (ACORES‐2, NCT04329195) are ongoing to further evaluate this issue.

No evidence‐based recommendations are available on the management of the immunosuppressive treatment among HT recipients affected with COVID‐19. Immunosuppressive regimen was downgraded in 72.5% of patients included in our case series. Antimetabolites increasing COVID‐19‐induced lymphopenia potentially induce SARS‐CoV‐2 replication. While mTOR inhibitors have an antiviral effect on CMV, there are no data supporting the efficacy and safety of mTOR inhibitors as antiviral therapy for COVID‐19. Experimental models have shown that calcineurin inhibitors block SARS‐CoV replication in vitro but clinical data supporting safety and efficacy of an immunosuppressive treatment based on cyclosporine in kidney transplant recipients remain weak [63]. Corticosteroids use has the potential to modulate the inflammatory response but has been associated with an increase in viral shedding. In the RECOVERY trial, the use of dexamethasone resulted in lower mortality among patients receiving respiratory support [64]. Further investigations are warranted to address the issue of immunosuppressive treatment's management in the specific setting of COVID‐19.

The limitations of this study are those associated with small observational studies. The association between baseline presentation and adverse outcomes was only assessed in univariate analysis as the limited sample size of our case series and number of events prevented the possibility to carry out a multivariable analysis. Moreover, we mostly included symptomatic patients which may have led to an overestimation of the case fatality of the disease. The prevalence of asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in HT recipients remains to be established. Management of immunosuppressive medications as well as administration of antiviral therapies was left at the discretion of transplant teams according to local practices, thus preventing the drawing of any conclusion. Only routine laboratory tests were performed in patients precluding any detailed evaluation of the inflammatory response to COVID‐19 in HT recipients. Furthermore, the comparison of the overall mortality among HT recipients in our three centres between the period of interest and the previous year should be cautiously interpreted considering the small number of confirmed COVID‐19 cases. Nonetheless, we believe that our findings could serve as incentive for larger studies with extended period of interest. Finally, a publication bias may have skewed our systematic review as well as meta‐analysis results. Indeed, while studies reporting on mortality could have been more easily published, reported results were from small observational studies with short‐term follow‐up. In addition, only available data authors considered interesting were included in the analyses.

In conclusion, this multicentre case series shows that the clinical course of COVID‐19 is aggressive in HT recipients even after reduction of immunosuppressive. Increased inflammation and lung involvement extent at admission in addition to pre‐existing diabetes and chronic kidney disease are associated with risk of death.

Funding

The authors have declared no funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no disclosure regarding the present studies.

Supporting information

Table S1. STROBE statement—checklist.

Table S2. Practical guide from the French Society of Transplantation for immunosuppressive therapy management in heart transplant recipient with COVID‐19.

Table S3. PRISMA—checklist.

Table S4. Systematic review of studies reporting outcomes among heart transplant recipients affected by COVID‐19.

Figure S1. Multiple polymerase chain reaction test results from nasopharyngeal swabs.

Figure S2. Flow chart of studies selection for the meta‐analysis.

Figure S3. Funnel plot analysis for diabetes mellitus (a), chronic kidney disease stage III or higher (b), hypertension (c), male gender (d), background use of ACE‐I/ARBs (e), number of background immunosuppressive therapies (f), and cardiac allograft vasculopathy (g).

References

- 1. COVID‐19 Map [Internet]. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. [Cité 4 Nov 2020.] Disponible sur: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou P, Yang X‐L, Wang X‐G, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020; 579: 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fried JA, Ramasubbu K, Bhatt R, et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID‐19. Circulation 2020; 141: 1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020; 323: 2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zendjebil S, Zeitouni M, Batonga M, et al. Acute multivessel coronary occlusion revealing COVID‐19 in a young adult. JACC Case Rep 2020; 2: 1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. López‐Medrano F, Aguado JM, Lizasoain M, et al. Clinical implications of respiratory virus infections in solid organ transplant recipients: a prospective study. Transplantation 2007; 84: 851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van de Beek D, Kremers WK, Del Pozo JL, et al. Effect of infectious diseases on outcome after heart transplant. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83: 304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pons S, Sonneville R, Bouadma L, et al. Infectious complications following heart transplantation in the era of high‐priority allocation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Intensive Care 2019; 9: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holzhauser L, Lourenco L, Sarswat N, Kim G, Chung B, Nguyen AB. Early experience of COVID‐19 in 2 heart transplant recipients: case reports and review of treatment options. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernández‐Ruiz M, Andrés A, Loinaz C, et al. COVID‐19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a single‐center case series from Spain. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fung M, Chiu CY, DeVoe C, et al. Clinical outcomes and serologic response in solid organ transplant recipients with COVID‐19: a case series from the United States. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathies D, Rauschning D, Wagner U, et al. A case of SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia with successful antiviral therapy in a 77‐year‐old man with a heart transplant. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID‐19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020; 141: 1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bansal M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID‐19. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020; 14: 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5: 811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Latif F, Farr MA, Clerkin KJ, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of recipients of heart transplant with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Cardiol 2020: e202159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iacovoni A, Boffini M, Pidello S, et al. A case series of novel coronavirus infection in heart transplantation from 2 centers in the pandemic area in the North of Italy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singhvi A, Barghash M, Lala A, et al. Challenges in heart transplantation during COVID‐19: a single center experience. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ketcham SW, Adie SK, Malliett A, et al. Coronavirus disease‐2019 in heart transplant recipients in Southeastern Michigan: a case series. J Card Fail 2020; 26: 457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bösch F, Börner N, Kemmner S, et al. Attenuated early inflammatory response in solid organ recipients with COVID‐19. Clin Transplant 2020: 34: e14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tschopp J, L'Huillier AG, Mombelli M, et al. First experience of SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in solid organ transplant recipients in the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoek RAS, Manintveld OC, Betjes MGH, et al. COVID‐19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a single‐center experience. Transpl Int 2020; 33: 1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yi SG, Rogers AW, Saharia A, et al. Early experience with COVID‐19 and solid organ transplantation at a US high‐volume transplant center. Transplantation 2020; 104: 2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li F, Cai J, Dong N. First cases of COVID‐19 in heart transplantation from China. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsu JJ, Gaynor P, Kamath M, et al. COVID‐19 in a high‐risk dual heart and kidney transplant recipient. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kates OS, Fisher CE, Stankiewicz‐Karita HC, et al. Earliest cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) identified in solid organ transplant recipients in the United States. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lima B, Gibson GT, Vullaganti S, et al. COVID‐19 in recent heart transplant recipients: clinicopathologic features and early outcomes. Transpl Infect Dis 2020; 22: e13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vaidya G, Czer LSC, Kobashigawa J, et al. Successful treatment of severe COVID‐19 pneumonia with clazakizumab in a heart transplant recipient: a case report. Transplant Proc 2020; 52: 2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mattioli M, Fustini E, Gennarini S. Heart transplant recipient patient with COVID‐19 treated with tocilizumab. Transpl Infect Dis 2020; 22: e13380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jang K, Khatri A, Majure DT. COVID‐19 leading to acute encephalopathy in a patient with heart transplant. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kadosh BS, Pavone J, Wu M, Reyentovich A, Gidea C. Collapsing glomerulopathy associated with COVID‐19 infection in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stachel MW, Gidea CG, Reyentovich A, Mehta SA, Moazami N. COVID‐19 pneumonia in a dual heart‐kidney recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Decker A, Welzel M, Laubner K, et al. Prolonged SARS‐CoV‐2 shedding and mild course of COVID‐19 in a patient after recent heart transplantation. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Serrano OK, Kutzler HL, Rochon C, et al. Incidental COVID‐19 in a heart‐kidney transplant recipient with malnutrition and recurrent infections: Implications for the SARS‐CoV‐2 immune response. Transpl Infect Dis 2020; 22: e13367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ahluwalia M, Givertz MM, Mehra MR. A proposed strategy for management of immunosuppression in heart transplant patients with COVID‐19. Clin Transplant 2020; 34: e14032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soquet J, Rousse N, Moussa M, et al. Heart retransplantation following COVID‐19 illness in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020; 39: 983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Felldin M, Søfteland JM, Magnusson J, et al. Initial report from a Swedish high‐volume transplant center after the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Transplantation 2021; 105: 108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rivinius R, Kaya Z, Schramm R, et al. COVID‐19 among heart transplant recipients in Germany: a multicenter survey. Clin Res Cardiol 2020; 109: 1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ammirati E, Travi G, Orcese C, et al. Heart‐Kidney Transplanted patient affected by COVID‐19 pneumonia treated with tocilizumab on top of immunosuppressive maintenance therapy. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2020; 29: 100596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vilaro J, Al‐Ani M, Manjarres DG, et al. Severe COVID‐19 after recent heart transplantation complicated by allograft dysfunction [Internet]. JACC Case Rep 2020; 2: 1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sperry BW, Khumri TM, Kao AC. Donor‐derived cell free DNA in a heart transplant patient with COVID‐19. Clin Transplant 2020; 34: e14070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ravanan R, Callaghan CJ, Mumford L, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and early mortality of wait‐listed and solid organ transplant recipients in England: a national cohort study. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kates OS, Haydel BM, Florman SS, et al. COVID‐19 in solid organ transplant: a multi‐center cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2020. [Internet]. [Cité 12 sept 2020.] Disponible sur: https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance‐article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa1097/5885162. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caraffa R, Bagozzi L, Fiocco A, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in the heart transplant population: a single‐centre experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2020; 58: 899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mastroianni F, Leisman DE, Fisler G, Narasimhan M. General and intensive care outcomes for hospitalized patients with solid organ transplants with COVID‐19. J Intensive Care Med 2020. [cité 5 Nov 2020]; Disponible sur: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7548542/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schtruk LE, Miranda J, Salles V, et al. COVID‐19 infection in heart transplantation: case reports. Arq Bras Cardiol 2020; 115: 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. García‐Cosío MD, Flores Hernán M, Caravaca Pérez P, López‐Medrano F, Arribas F, Delgado Jiménez J. Heart transplantation during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: follow‐up organization and characteristics of infected patients. Rev Esp Cardiol 2020; 73: 1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Al‐Darzi W, Aurora L, Michaels A, et al. Heart transplant recipients with confirmed 2019 novel coronavirus infection: the Detroit experience. Clin Transplant 2020; 34: e14091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rahman F, Liu STH, Taimur S, et al. Treatment with convalescent plasma in solid organ transplant recipients with COVID‐19: experience at large transplant center in New York City. Clin Transplant 2020; 34: e14089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sharma P, Chen V, Fung CM, et al. COVID‐19 outcomes among solid organ transplant recipients: a case‐control study. Transplantation 2021; 105: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fiocco A, Ponzoni M, Caraffa R, et al. Heart transplantation management in northern Italy during COVID‐19 pandemic: single‐centre experience. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bottio T, Bagozzi L, Fiocco A, et al. COVID‐19 in heart transplant recipients: a multicenter analysis of the Northern Italian outbreak. JACC Heart Fail 2020; 9: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Coll E, Fernández‐Ruiz M, Sánchez‐Álvarez JE, et al. COVID‐19 in transplant recipients: the Spanish experience. Am J Transplant 2020; 1 (ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Manuel O, Estabrook M, American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice . RNA respiratory viral infections in solid organ transplant recipients: guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant 2019; 33: e13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Oyelade T, Alqahtani J, Canciani G. Prognosis of COVID‐19 in patients with liver and kidney diseases: an early systematic review and meta‐analysis. Trop Med Infect Dis 2020; 5: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P, et al. Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID‐19? A meta‐analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020; 14: 535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in‐hospital death of patients with COVID‐19. Kidney Int 2020; 97: 829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang X, Fang X, Cai Z, et al. Comorbid chronic diseases and acute organ injuries are strongly correlated with disease severity and mortality among COVID‐19 patients: a systemic review and meta‐analysis. Research 2020; 2020: 2402961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181: 271.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, et al. Effect of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2. Circulation 2005; 111: 2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, et al. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rodriguez‐Cubillo B, de la Higuera MAM, Lucena R, et al. Should cyclosporine be useful in renal transplant recipients affected by SARS‐CoV‐2? Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Lim WS, et al.Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid‐19 – preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020. [Cité 12 sept 2020]; Disponible sur: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7383595/. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. STROBE statement—checklist.

Table S2. Practical guide from the French Society of Transplantation for immunosuppressive therapy management in heart transplant recipient with COVID‐19.

Table S3. PRISMA—checklist.

Table S4. Systematic review of studies reporting outcomes among heart transplant recipients affected by COVID‐19.

Figure S1. Multiple polymerase chain reaction test results from nasopharyngeal swabs.

Figure S2. Flow chart of studies selection for the meta‐analysis.

Figure S3. Funnel plot analysis for diabetes mellitus (a), chronic kidney disease stage III or higher (b), hypertension (c), male gender (d), background use of ACE‐I/ARBs (e), number of background immunosuppressive therapies (f), and cardiac allograft vasculopathy (g).