Abstract

Zinc inhibits replication of the SARS‐CoV virus. We aimed to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and biological effect of administering high‐dose intravenous zinc (HDIVZn) to patients with COVID‐19. We performed a Phase IIa double‐blind, randomized controlled trial to compare HDIVZn to placebo in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. We administered trial treatment per day for a maximum of 7 days until either death or hospital discharge. We measured zinc concentration at baseline and during treatment and observed patients for any significant side effects. For eligible patients, we randomized and administered treatment to 33 adult participants to either HDIVZn (n = 15) or placebo (n = 18). We observed no serious adverse events throughout the study for a total of 94 HDIVZn administrations. However, three participants in the HDIVZn group reported infusion site irritation. Mean serum zinc on Day 1 in the placebo, and the HDIVZn group was 6.9 ± 1.1 and 7.7 ± 1.6 µmol/l, respectively, consistent with zinc deficiency. HDIVZn, but not placebo, increased serum zinc levels above the deficiency cutoff of 10.7 µmol/l (p < .001) on Day 6. Our study did not reach its target enrollment because stringent public health measures markedly reduced patient hospitalizations. Hospitalized COVID‐19 patients demonstrated zinc deficiency. This can be corrected with HDIVZn. Such treatment appears safe, feasible, and only associated with minimal peripheral infusion site irritation. This pilot study justifies further investigation of this treatment in COVID‐19 patients.

Keywords: COVID‐19, randomized controlled trial, trial protocol, zinc

Abbreviations

- HDIVZn

high dose intravenous zinc

- HFNC

high‐flow nasal cannula

- NIV

noninvasive ventilation

1. INTRODUCTION

Cheap, safe, and easily administered interventions to improve outcomes associated with COVID‐19 infection remain an important goal. Zinc and Zn‐salts inhibit viral infections in clinical and experimental settings, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 including replication of SARS‐coronavirus (SARS‐CoV). 8 Thus, zinc supplementation might be beneficial in patients with COVID‐19. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 Clinical trials have been registered to test the efficacy of zinc against COVID, mostly with oral zinc supplementation. 18 However, the bioavailability of enterally administered zinc is low. 15 Thus, logically, intravenous zinc at a high dose should be the preferred mode of administration. 15 Unfortunately, no studies have assessed the feasibility, safety, and impact on zinc levels of high‐dose intravenous zinc (HDIVZn). We designed a Phase IIa pilot double‐blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) to determine the feasibility, safety, and biological efficacy of HDIVZn in subjects with COVID‐19.

2. METHODS

2.1. Human ethics

The Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study (HREC/62996/Austin‐2020‐208572(v3) and the trial was prospectively registered (Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial Register Registration no. ACTRN12620000454976).

2.2. Study protocol and drug

A detailed clinical trial protocol has been published previously. 19 Briefly, we randomized consenting COVID‐19 confirmed hospitalized adults with oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 94% or less while on ambient air to either daily HDIVZn or saline placebo. Colorless pharmaceutical grade Zinc Chloride (ZnCl2) stock solution obtained from Phebra Pty Ltd was diluted in 250 ml of normal saline and infused via peripheral intravenous access over 3 h at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day (elemental zinc concentration, 0.24 mg/kg/day) for a maximum of 7 days, or until hospital discharge or death. The investigators, study coordinators, treating physicians, bedside nurses, and patients/family remained blinded to the allocated study solution.

The serum trace metal analysis was carried out by Austin Pathology using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP‐MS).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviation and compared between groups with the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and compared with Fisher's exact tests. Variables are presented over time in line plots and compared between groups with a mixed‐effect generalized linear model with Gaussian distribution, considering the patients as a random effect to account for repeated measurements, and with the time of measurement (as a continuous variable), group of randomization and an interaction between time x group as fixed effects. A two‐sided value of p < .05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

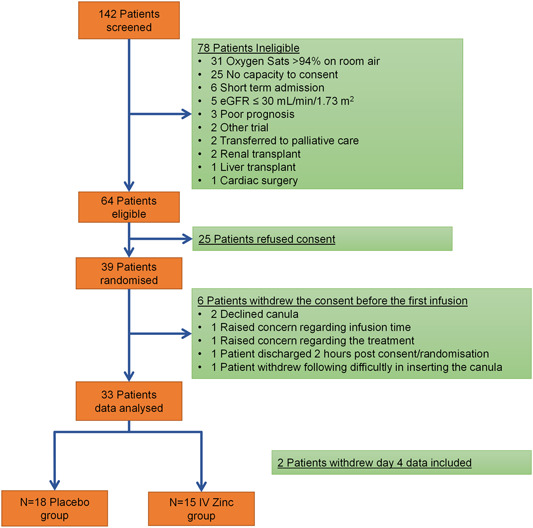

We randomized 33 adults to either HDIVZn (n = 15) or placebo (n = 18; Figure 1 and Table 1). Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic cardiovascular disease were frequently present. We observed no drug‐related severe adverse events during 94 administrations of HDIVZn However, three HDIVZn patients reported infusion site irritation, two on Day 4, and one on Day 6.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing patient recruitment and randomisation

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Baseline Characteristics recorded on day 1 before receiving the first injection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HDIVZn | Control | ||

| (n = 15) | (n = 18) | p | |

| Age, years (range) | 59.8 ± 16.8 (25–84) | 63.8 ± 16.9 (31–95) | .550 |

| Male gender, N (%) | 11 (73.3) | 10 (55.5) | .711 |

| Weight, kg (range) | 86.6 ± 23.1 (50–128) | 73.9 ± 16.8 (48 –100) | .073 |

| Co‐existing disorders, N (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 7 (46.7) | 9 (50.0) | .999 |

| Diabetes | 3 (20.0) | 3 (16.7) | .999 |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 4 (26.7) | 3 (16.7) | .786 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.1) | .549 |

| Cirrhosis | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) | .294 |

| Hepatic failure | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | .999 |

| Drugs on Day 1, N (%) | |||

| Dexamethasone | 12 (80.0) | 13 (72.2) | .911 |

| Remdesivir | 5 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | .999 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| Zinc, µmol/l (range) | 7.7 ± 1.6 (4.8–10.5) | 6.9 ± 1.1 (4.6–8.5) | .122 |

| Creatinine, µmol/l (range) | 71.4 ± 24.9 (37–120) | 80.4 ± 33.7 (37–156) | .718 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/l (range) | 123.7 ± 72.7 (10–223) | 91.4 ± 75 (4–294) | .126 |

| Troponin I, ng/l (range) | 91.2 ± 223.2 (4–786) | 18.1 ± 21.2 (2–71) | .981 |

| Lactate, mmol/l (range) | 0.661 ± 2.1 (0.8–2.9) | 0.634 ± 2.4 (0.7–3.1) | .868 |

| White blood cell count, ×103 cells/mm3 (range) | 5.5 ± 2.7 (2.2–10.7) | 6.6 ± 3.1 (2.4–12.7) | .193 |

Note: Values are mean ± SD or percentages as indicated; range indicates Min and Max values.

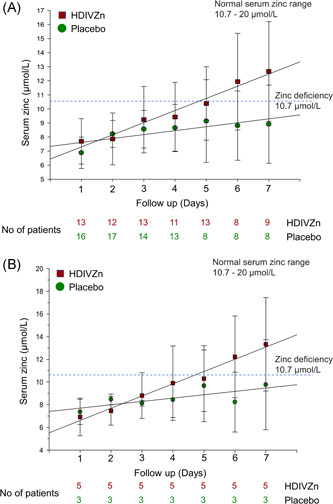

Mean serum zinc on Day 1 in the placebo and the HDIVZn group was 6.9 ± 1.1 and 7.7 ± 1.6 µmol/l, respectively, consistent with zinc deficiency. HDIVZn increased serum zinc levels above the deficiency cutoff of 10.7 µmol/l (p < .001) on Day 6. In contrast, serum zinc levels with placebo remained below this value (Figure 2A). In contrast, serum copper, calcium, and magnesium were within the normal range at baseline and were not affected by HDIVZn. As most of the patients enrolled in our study were donating blood across multiple trials, we had limited ability to collect enough blood samples to perform all the planned biochemical tests daily, including the serum zinc levels. Figure 2B shows the serum zinc for eight patients who had their serum zinc determined at all the time points across the 7‐day study period.

Figure 2.

High dose intravenous zinc (HDIVZn) increased serum zinc levels in zinc‐deficient COVID‐19 patients

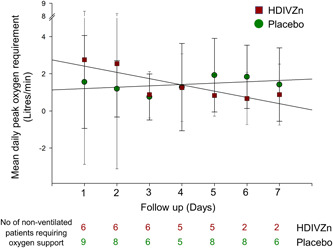

The primary outcome in non‐ventilated patients was assessed as the level of oxygenation expressed as oxygen flow (in liters/min) required to maintain blood oxygen levels (SpO2) above 94% and the worst (lowest) PaO2/FiO2 ratio in ventilated patients. Our study did not reach its target enrollment because stringent public health measures markedly reduced new patient presentations to zero. Consequently, we could not adequately assess the primary outcome of whether HDIVZn reduced the level of oxygenation in non‐ventilated (Figure 3) or improved the PaO2/FiO2 ratio in the four ventilated patients (data not shown) and other clinical efficacy outcomes (Table 2).

Figure 3.

The effect of high dose intravenous zinc (HDIVZn) on mean daily peak oxygenation requirement in COVID‐19 patients

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

| Comparison of ordinal scale | ||

|---|---|---|

| HDIVZn | Control | |

| (n = 15) | (n = 18) | |

| Eight‐level ordinal scale at Day 1, N (%) | ||

| 3. Hospitalized, no supplemental oxygen | 6 (40.0) | 9 (50.0) |

| 4. Hospitalized, with supplemental oxygen | 5 (33.3) | 8 (44.4) |

| 5. Hospitalized, NIV, and/or HFNC | 1 (6.7) | 1 (5.6) |

| 6. Hospitalized, mechanical ventilation | 3 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Eight‐level ordinal scale at Day 7, N (%) | ||

| 2. Not hospitalized, with limitations | 2 (15.4) | 6 (33.3) |

| 3. Hospitalized, no supplemental oxygen | 6 (46.2) | 6 (33.3) |

| 4. Hospitalized, with supplemental oxygen | 2 (15.4) | 5 (27.8) |

| 5. Hospitalized, NIV, and/or HFNC | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) |

| 6. Hospitalized, mechanical ventilation | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| 8. Death | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Eight‐level ordinal scale at Day 14, N (%) | ||

| 0. Not hospitalized, no infection | 2 (14.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| 2. Not hospitalized, with limitations | 5 (35.7) | 10 (55.6) |

| 3. Hospitalized, no supplemental oxygen | 3 (21.4) | 2 (11.1) |

| 4. Hospitalized, with supplemental oxygen | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| 5. Hospitalized, NIV, and/or HFNC | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) |

| 8. Death | 1 (7.1) | 3 (16.7) |

| Eight‐level ordinal scale at Day 28, N (%) | ||

| 0. Not hospitalized, no infection | 2 (14.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| 1. Not hospitalized, without limitation | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2. Not hospitalized, with limitations | 7 (50.0) | 12 (66.7) |

| 3. Hospitalized, no supplemental oxygen | 1 (7.1) | 1 (5.6) |

| 4. Hospitalized, with supplemental oxygen | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 8. Death | 2 (14.3) | 3 (16.7) |

Abbreviations: HFNC, high‐flow nasal cannula; NIV, noninvasive ventilation.

4. DISCUSSION

Zinc therapy is logical in COVID‐19 because of the inhibitory effect of zinc on viral replication and because low zinc levels appear common in COVID‐19 patients. 20 , 21 In a recently published study among a cohort of 47 COVID‐19 patients, 27 (57.4%) were found to be zinc deficient. 20 In a Japanese study among a cohort of 29 COVID‐19 patients, 9 (31%) were found to be zinc deficient. 21

There is no globally accepted cutoff level for zinc deficiency. However, Hotz et al. 22 based on the data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) suggested that for males greater than 10 years of age serum zinc levels below 61–74 μg/dl (9.3–11.3 µmol/l) depending on the fasting status can be considered as a cutoff value for zinc deficiency. Furthermore, the International Zinc Nutrition Consultative Group (IZiNCG) 23 has defined 10.7 µmol/l as a cutoff value for zinc deficiency, and this value was previously used in an Australian study. 24 Serum zinc levels less than 60 μg/dl (9.1 µmol/l) are defined as clinical zinc deficiency in Japan. However, in a recently published Japanese study, the zinc deficiency cutoff value was set at <70 μg/dl (10.7 µmol/l) to enable direct comparison with domestic and international information. 21

A previous study has determined that the mean serum zinc in the Australian population is 13 ± 2.4 and 13 ± 2.5 µmol/l for men and women, respectively. 24 One of the leading causes of zinc deficiency is aging; however, in a well‐characterized cohort of healthy Australians with an average age of 70.6 ± 7 years, the serum zinc levels were 12.7 ± 2.5 µmol/l. 25 In our study, 100% of patients (33/33) were zinc deficient as the mean serum zinc values in the placebo, and the HDIVZn group were 6.9 ± 1.1 and 7.7 ± 1.6 µmol/l, respectively, well below the zinc deficiency cutoff value of 10.7 µmol/l. Therefore, our results suggest that such zinc deficiency seen in COVID‐19 patients may be an acute phase reaction, specifically due to COVID‐19 infection. 26

Zinc deficiency has been associated with a twofold increase in complication rates, 20 greater risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, longer hospital stay, and increased mortality 20 with an independent relationship between low serum zinc level and disease severity. 21 A recent European study with 35 participants confirmed that most COVID‐19 patients were zinc deficient with lower zinc levels in non‐survivors. 27 Given the above observations, various investigators have hypothesized that zinc therapy may be beneficial in COVID‐19, 11 , 12 , 13 but zinc bioavailability from enteral administration is low, and the low dosage is inadequate. 15

A recently published study with four participants suggested that oral administration of elemental zinc to a maximum amount not exceeding 200 mg (zinc salt lozenges) was well tolerated and may have been associated with positive recovery from COVID‐19. 28 In contrast, a single‐center retrospective study of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 (n = 242) determined a lack of association between zinc sulfate intake (100 mg elemental zinc daily) and survival. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has been shown to act as a zinc ionophore, increasing zinc uptake and inducing apoptosis in malignant cells. 13 , 29 A recent trial by Boulware et al. 29 determined that zinc, in combination with HCQ, was ineffective as there was no evidence that HCQ, in combination with zinc, reduced the incidence of COVID‐19 after a high‐risk exposure. However, the authors conceded that the study could not be considered conclusive. It was limited by the small sample size of the zinc cohort exacerbated by the lack of details regarding zinc formulation, dose, and treatment duration.

In contrast, Derwand et al. 30 showed that oral supplementation with 50 mg elemental zinc (zinc sulfate), in combination with HCQ (200 mg twice a day), and azithromycin (500 mg per day) for five consecutive days was associated with significantly fewer hospitalizations. Similarly, Carlucci et al., 31 using the same combination determined that 50 mg elemental zinc (zinc sulfate), when added to HCQ and azithromycin, decreased the mortality and hospitalization. Several shortcomings of these studies include the fact that interventions were not controlled nor blinded. Patients were not randomized or monitored for various other laboratory parameters. However, the most significant limitation of the studies mentioned above is the lack of data showing whether oral zinc supplementation on its own or in combination with HCQ indeed improved the serum zinc status among COVID‐19 patients.

The upper daily oral intake limit for elemental zinc is 40 mg/day as defined by the National Institutes of Health and a lower 25 mg/day as defined by the European Food Safety Authority. A recent study noted that enteral delivery (via a nasogastric feeding tube) of 100–150 mg/day elemental zinc supplied as zinc acetate (brand name Nobelzin) takes between 14 and 24 days to correct zinc deficiency, defined as serum zinc less than 70 μg/dl (equivalent to 10.7 µmol/l) in hospitalized Japanese COVID‐19 patients. 21 In comparison, our HDIVZn regimen using an elemental zinc dose ranging from a minimum daily dose of 12 mg (in a 50 kg patient) to a maximum of 30.7 mg (in a 128 kg patient) corrected zinc deficiency within a week without any toxicity or side effects. The need to use significantly higher doses of zinc than the recommended upper daily oral intake stems from an analysis by Hambidge et al., 32 indicating that the maximal absorption (A max) for zinc via oral delivery is only ≈7 mg Zn/day. This low A max is due to the molecular complexities of oral zinc absorption into and across the enterocyte and basolateral membrane. Overall, our study suggests that intravenous zinc overcomes low A max of oral zinc supplementation. Furthermore, intravenous zinc may be superior to oral zinc supplementation in rectifying the acute phase zinc deficiency seen in COVID‐19 patients; however, a direct comparative study (intravenous vs. oral Zn) is warranted.

In summary, our study provides the first evidence showing the safety and feasibility of intravenous zinc treatment and the ability of HDIVZn to reverse the acute phase zinc deficiency associated with COVID‐19. These findings support further investigation of this treatment in larger RCTs.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Oneel Patel, Rinaldo Bellomo, and Joseph Ischia designed and directed the project. Christine McDonald, Daryl Jones, and Damien Bolton contributed to the design and implementation of the trial protocol. Vidyasagar Chinni, John El‐Khoury, Marlon Perera, and Jason Trubiano collected the data. Ary S. Neto performed the statistical analysis. Emily See developed the data collection database. Oneel Patel, Rinaldo Bellomo, and Joseph Ischia wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, edited, and commented on the manuscript.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jmv.26895.

Patel O, Chinni V, El‐Khoury J, et al. A pilot double‐blind safety and feasibility randomized controlled trial of high‐dose intravenous zinc in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients. J Med Virol. 2021;93:3261‐3267. 10.1002/jmv.26895

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hulisz D. Efficacy of zinc against common cold viruses: an overview. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44(5):594‐603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suara RO, Crowe JE Jr. Effect of zinc salts on respiratory syncytial virus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):783‐790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li D, Wen LZ, Yu H. Observation on clinical efficacy of combined therapy of zinc supplement and jinye baidu granule in treating human cytomegalovirus infection. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2005;25(5):449‐451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Femiano F, Gombos F, Scully C. Recurrent herpes labialis: a pilot study of the efficacy of zinc therapy. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(7):423‐425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Korant BD, Kauer JC, Butterworth BE. Zinc ions inhibit replication of rhinoviruses. Nature. 1974;248(449):588‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lanke K, Krenn BM, Melchers WJ, Seipelt J, van Kuppeveld FJ. PDTC inhibits picornavirus polyprotein processing and RNA replication by transporting zinc ions into cells. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 4):1206‐1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Si X, McManus BM, Zhang J, et al. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate reduces coxsackievirus B3 replication through inhibition of the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway. J Virol. 2005;79(13):8014‐8023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. te Velthuis AJ, van den Worm SH, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. Zn2+ inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLOS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arnold JJ, Ghosh SK, Cameron CE. Poliovirus RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase (3D(pol)). Divalent cation modulation of primer, template, and nucleotide selection. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(52):37060‐37069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butterworth BE, Korant BD. Characterization of the large picornaviral polypeptides produced in the presence of zinc ion. J Virol. 1974;14(2):282‐291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wessels I, Rolles B, Rink L. The potential impact of zinc supplementation on COVID‐19 pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skalny A, Rink L, Ajsuvakova O, et al. Zinc and respiratory tract infections: perspectives for COVID‐19 (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2020;46(1):17‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rahman MT, Idid SZ. Can Zn be a critical element in COVID‐19 treatment? Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jayawardena R, Sooriyaarachchi P, Chourdakis M, Jeewandara C, Ranasinghe P. Enhancing immunity in viral infections, with special emphasis on COVID‐19: a review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):367‐382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ischia J, Bolton DM, Patel O. Why is it worth testing the ability of zinc to protect against ischaemia reperfusion injury for human application. Metallomics. 2019;11(8):1330‐1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Kane D, Gibson L, May CN, et al. Zinc preconditioning protects against renal ischaemia reperfusion injury in a preclinical sheep large animal model. BioMetals. 2018;31(5):821‐834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rao K, Sethi K, Ischia J, et al. Protective effect of zinc preconditioning against renal ischemia reperfusion injury is dose dependent. PLOS One. 2017;12(7):e0180028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pal A, Squitti R, Picozza M, et al. Zinc and COVID‐19: basis of current clinical trials. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Perera M, El‐Khoury J, Chinni V, et al. Randomised controlled trial for high‐dose intravenous zinc as adjunctive therapy in SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19) positive critically ill patients: trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e040580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jothimani D, Kailasam E, Danielraj S, et al. COVID‐19: poor outcomes in patients with zinc deficiency. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:343‐349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yasui Y, Yasui H, Suzuki K, et al. Analysis of the predictive factors for a critical illness of COVID‐19 during treatment relationship between serum zinc level and critical illness of COVID‐19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:230‐236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hotz C, Peerson JM, Brown KH. Suggested lower cutoffs of serum zinc concentrations for assessing zinc status: reanalysis of the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (1976‐1980). Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(4):756‐764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. International Zinc Nutrition Consultative Group , Brown KH, Rivera JA, et al. International Zinc Nutrition Consultative Group (IZiNCG) technical document #1. Assessment of the risk of zinc deficiency in populations and options for its control. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(1 suppl 2):99‐203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beckett JM, Ball MJ. Zinc status of northern Tasmanian adults. J Nutr Sci. 2015;4:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rembach A, Hare DJ, Doecke JD, et al. Decreased serum zinc is an effect of ageing and not Alzheimer's disease. Metallomics. 2014;6(7):1216‐1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duggan C, MacLeod WB, Krebs NF, et al. Plasma zinc concentrations are depressed during the acute phase response in children with falciparum malaria. J Nutr. 2005;135(4):802‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heller RA, Sun Q, Hackler J, et al. Prediction of survival odds in COVID‐19 by zinc, age and selenoprotein P as composite biomarker. Redox Biol. 2020;38:101764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Finzi E. Treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 with high dose oral zinc salts: a report on four patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:307‐309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boulware DR, Pullen MF, Bangdiwala AS, et al. A randomized trial of hydroxychloroquine as postexposure prophylaxis for COVID‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):517‐525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Derwand R, Scholz M, Zelenko V. COVID‐19 outpatients: early risk‐stratified treatment with zinc plus low‐dose hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: a retrospective case series study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(6):106214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carlucci PM, Ahuja T, Petrilli C, Rajagopalan H, Jones S, Rahimian J. Zinc sulfate in combination with a zinc ionophore may improve outcomes in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients. J Med Microbiol. 2020;69(10):1228‐1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hambidge KM, Miller LV, Westcott JE, Sheng X, Krebs NF. Zinc bioavailability and homeostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1478S‐1483S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.