Abstract

Aim

This study was conducted to examine the experiences and feelings of nurses who have children when caring for patients with coronavirus disease (COVID‐19).

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected the whole world, including Turkey where this study was conducted. Nurses are among healthcare professionals who are intensively working at the forefront during this pandemic. Countries are implementing many policies to fight this pandemic. Turkey also has implemented protective measures related to travel, sports, and cultural activities and has prohibited social meetings.

Method

The study was conducted with 26 nurses working in COVID‐19 clinics of two hospitals in eastern Turkey between May and July 2020 using a qualitative descriptive design.

Findings

Nurses who had children longed for their children and worried about them. They were afraid of getting infected with the disease and transmitting it. Based on content analysis, the themes of the study were determined as follows: (1) longing (longing for children and longing for the pre‐pandemic period), (2) fear (fear of transmitting the disease and fear of death), (3) despair, (4) concern (concern resulting from working in a different clinic, concern resulting from lack of knowledge, and concern resulting from lack of protective equipment), and (5) professional responsibility (professional awareness and love for the profession).

Conclusion

Nurses were away from their families for a long time because of the fear of getting infected with COVID‐19 and transmitting it. They longed for their children and experienced desperation, fear, and anxiety. They loved their profession and were not considering quitting their profession.

Implications for nursing and health policy

Nurses working in COVID‐19 units wear protective equipment and work for a long time under difficult conditions. In addition, nurses who have children are separated from their children because of the fear of transmitting COVID‐19. Therefore, nurses caring for COVID‐19 patients should alternately be replaced by nurses working in other services. They should be given the opportunity to rest and spend time with their loved ones if they are not carriers of COVID‐19.

Keywords: child relations, COVID‐19, family relations, mother, nursing care, pandemics, professional practice, Turkey

Introduction

COVID‐19 is a highly contagious disease that first appeared in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread around the world, causing a pandemic (Shi et al., 2020). This pandemic has a negative effect on the quality of life of patients. At the same time, it has caused many people to be hospitalized for extended durations to receive intensive treatment and care. Moreover, it has resulted in hundeds of thousands of deaths (Chen et al. 2020). The need for nurses has increased during this pandemic, as they play an important role in the prevention of disease and in the treatment and care of patients (Lai et al. 2020).

Nurses are healthcare professionals who are working intensively for the care and treatment of patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The workload of nurses has increased during the pandemic period (Lai et al. 2020). Nurses who care for COVID‐19 patients take many protective measures, particularly including the use of personal protective equipment and observance of hygiene rules to avoid transmitting the disease (Sun et al. 2020). However, we found that sometimes nurses lack sufficient personal protective equipment. In addition, they lacked knowledge about the impact of coronavirus on humans and the required protective measures. Most importantly, nurses who had children had to stay away for a long time from them and other relatives they were caring for a long time. All these aspects can cause nurses to experience many mental health issues, such as intense stress, anxiety, hopelessness, desperation, burnout, and depression (Lai et al. 2020; Mo et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020). In a qualitative study conducted to examine the psychology of nurses caring for COVID‐19 patients found that nurses experienced fatigue, exhaustion, desperation, and fear and were worried about their patients and their family members (Sun et al. 2020). Studies conducted during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic revealed that healthcare professionals were afraid of transmitting the disease to their spouses, children, and friends, and experienced stress, anxiety, and uncertainty and that some nurses thought of resigning (Bukhari et al. 2016; Lai et al. 2020; Mo et al. 2020).

The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected the daily life of people across the world, including Turkey (Cai et al. 2020). Countries are implementing many policies to fight the pandemic (WHO 2020a, 2020b). Turkey also has implemented protective measures related to travel, sports, and cultural activities and has prohibited social meetings. The government has been trying to ensure the safety of the public through various measures such as curfews and closure of schools and shopping malls (Republc of Turkey Mnstry of Health 2020a, 2020b). Such measures have caused children to worry as much as adults. Many reasons, such as the fear of infection, insufficient information, being at home all day, lack of play, and lack of face‐to‐face communication with classmates and teachers can have negative and permanent effects on children (Cao et al. 2020; Jiao et al. 2020). A study revealed higher post‐stress trauma in children who were quarantined than in children who were not (Brooks et al. 2020). Another study revealed that children experienced psychological and behavioral problems, distractibility, and irritability and were afraid to ask questions about the pandemic (Jiao et al. 2020). During this process, children often need their parents’ interest and support more than ever. Parents’ attitudes toward the epidemic can affect children’s reactions (Khalid et al. 2016; Kim 2018; Smith et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2020).

The parent–child relationship consists of biological, psychological, and social relationships. This relationship affects the child’s emotional, linguistic, and social development. Parents’ love, interest, sharing, and communication with their children develop a sense of security in the child (Dereli & Dereli 2017; Tam et al. 2012). However, the interruption of this relationship due to disturbances, such as war, migration, and epidemics, can cause both the child and the parent to experience negative feelings. The child can experience unhappiness, longing, post‐traumatic stress disorder, sadness, uneasiness, nervousness, restlessness, insecurity, malnutrition, and attachment problems. These problems can have a negative effect on the child’s physical and mental development now and in the future (Arabacı et al. 2016; Aydın et al. 2017; Hacıhasanoğlu & Yıldırım 2018).

Nurses are among the healthcare professionals who have worked intensively on the forefront during the COVID‐19 pandemic. During this crisis, nurses have avoided going home to reduce the risk of infecting other people and their loved ones with the disease, and they have begun to live temporarily in places such as dormitories, hotels, and guest houses. There are mothers and fathers among these nurses. During the epidemic, both nurse parents and their children feel a longing for each other and wish to go back to pre‐epidemic times. In addition, nurses can have difficulties explaining this process to their children (Cai et al. 2020; Lai et al. 2020; Mo et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020).

COVID‐19 is a major pandemic (Sun et al. 2020). This study sought to answer the questions: What are the feelings of nurses who are working and must be away from their children in this pandemic? What are the experiences of nurses working during the COVID‐19 pandemic?

Aim

This study was conducted to examine the experiences and feelings of parent nurses who care for COVID‐19 patients.

Methodology

Study design and sampling

This study was conducted with a qualitative descriptive design in order to discover the feelings and experiences of parent nurses working with novel coronavirus patients (Kim, Sefcik, & Bradway 2017). It examined nurses caring for patients with COVID‐19 in one state hospital and one university hospital in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey between March and July 2020. Both hospitals provide similar services.

A purposeful sampling method was used in this study. Nurses who cared for COVID‐19 patients and who were parents constituted the sample population of the study (Sun et al. 2020). In qualitative studies, the data can be obtained directly from field study observations, in‐depth, open‐ended interviews, and written documents (Patton 2005). In this study, the data were obtained from the writing of nurses.

First, the names and email addresses of nurses working in the two hospitals who were providing care to COVID‐19 patients and who had children were collected. It was found that at the two hospitals, a total of 120 nurses were providing care to COVID‐19 patients, and 70 of these nurses had children. An email including information about the aim and scope of the study was sent to the 70 nurses, and they were asked to participate in the study. Thirty nurses answered the email and reported that they wanted to participate. However, four nurses left the study during the data collection phase. The study was completed with a total of 26 nurses, 16 females and 10 males. Although there is no rule specified for sample size in literature for qualitative studies, situations such as the data repeating and not obtaining additional data are important indicators for terminating the application. Data saturation was reached when nurses began to use similar or same expressions and was achieved with 26 nurses.

Data collection

In order to collect data, the researchers prepared four open‐ended, basic questions: (1) How did working during the coronavirus pandemic affect your interactions with your child? (2) Can you explain the feelings and experiences you have been through during the pandemic? (3) How did working during COVİD‐19 pandemic affect your thoughts about your profession? (4) What kind of problems did you experience while providing care to your patients during COVİD‐19 pandemic?

After the questions were written in a Word file by the researchers, they were sent to the email addresses of nurses who wanted to participate in the study. The nurses were asked to answer within a week. The education levels of the nurses who agreed to participate in the study were associate degree, undergraduate degree, and graduate degree. The differences in the level of education do not change the duties and responsibilities of nurses in our country. Twenty‐six nurses recorded their answers to these questions on a Word document and sent it to us via email. Each nurse wrote down 2‐3 pages. A total of 70 written pages were obtained.

Ethical approval

Before starting the study, permission was granted from the Ministry of Health and the hospitals. In addition, permission was obtained from the Fırat University Non‐interventional Ethics Committee (393580). Written consent was obtained from the nurses who participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis

The data obtained were evaluated using a content analysis method (Graneheim & Lundman 2004). The material analyzed was the communications of parent nurses providing care to COVID‐19 patients. The data were analyzed using a qualitative content analysis method. A content analysis method is a research technique focused on deriving reproducible, valid results regarding the content of data (Graneheim & Lundman 2004). The researchers combined the texts sent by the nurses. Both researchers read the written texts again and again independently of each other, and they found and coded the same, similar, and different expressions. The researchers then combined their data analyses and compared the codes. The researchers continued discussing the codes until they came to an agreement on all of them. After it was found that there were no significant differences between the codes, the main and secondary themes of the study were determined.

Findings

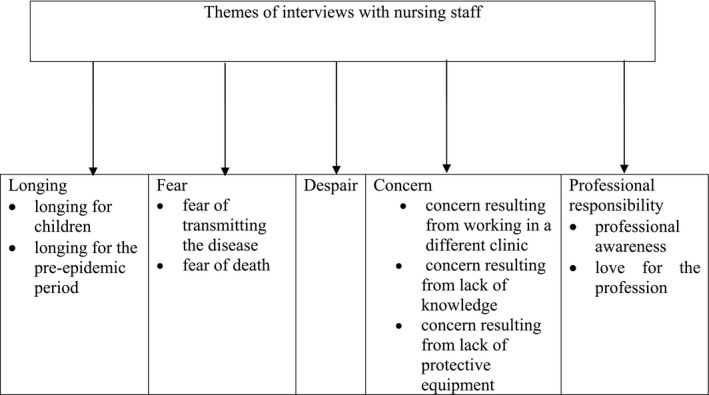

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the nurses. It was found that 61.6% of the nurses in the study were between 29 and 37 years of age, 65.5% were women, 42.3% had been nurses for five to eight years, and 65.5% were working in a training and research hospital. It was found that 77% of the nurses had one to two children, and the average age of the children was 5.45 ± 3.28. As a result of the content analysis, five main themes and nine sub‐themes were determined: (1) longing (longing for children, longing for the pre‐epidemic period), (2) fear (fear of transmitting the disease, fear of death), (3) despair, (4) concern (concern resulting from working in a different clinic, concern resulting from lack of knowledge, concern resulting from lack of protective equipment), and (5) professional responsibility (professional awareness, love for the profession) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of nurses’ descriptive characteristics (n = 26)

| Descriptive characteristic | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||

| 20–28 | 5 | 19.2 |

| 29–37 | 16 | 61.6 |

| 38 and over | 5 | 19.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 16 | 65.5 |

| Male | 10 | 34.5 |

| Hospital | ||

| State hospital | 16 | 65.5 |

| University hospital | 10 | 34.5 |

| Clinic previously worked in | ||

| Brain surgery | 4 | 15.3 |

| Operating room | 3 | 11.5 |

| Cardiology | 2 | 8.1 |

| General surgery | 3 | 11.5 |

| Internal diseases | 4 | 15.3 |

| Endocrine | 3 | 11.5 |

| Chest diseases intensive care | 4 | 15.3 |

| Pediatry clinic | 3 | 11.5 |

| Years worked as nurse | ||

| 1–4 years | 9 | 30.8 |

| 5–8 years | 11 | 42.3 |

| 9–12 years | 7 | 26.9 |

| Level of education | ||

| Two‐year degree | 5 | 19.2 |

| Undergraduate degree | 17 | 65.3 |

| Graduate degree | 4 | 15.5 |

| Number of children | ||

| 1‐2 | 20 | 76.9 |

| 3‐4 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Average age of children | ||

| 5.45 ± 3.28 | ||

Figure 1.

Themes of the content analysis.

Longing

Nurses could not go to their homes for fear of transmitting COVID‐19 to their children and other family members, and they were staying in hotels or dormitories assigned by the hospital administration. Some of the nurses had sent their children to live with other relatives, such as grandmothers or aunts. They could not see their children regularly, touch them, or spend time with them. They missed their children very much.

The sub‐themes of this section are nurses’ longing for their children and longing for pre‐epidemic days.

Longing for children

I haven’t seen my child for 1.5 months. I can only hear his voice on the phone. He says ‘come home, Dad; I miss you so much’. They say that he tries to get in my room and wear my clothes. I miss him very much, I feel desperate… (nurse, male, 30 years old).

I haven’t stayed at home for about a month. I just go home once or twice a week to see my daughter from afar. Sometimes my daughter comes onto the balcony of our house and sometimes in front of the door. I cannot hug her; I cannot smell her. My daughter asks me ‘why don’t you hug me, Mum? I love you so much; don’t you love me?’ I tell her that I love her very much, but I cannot hold her right now…When these days are gone, the first thing that I will do is hug my daughter as much as I want (nurse, female, 35 years old).

…I love my children very much; they are my hopes for tomorrow. It is very boring and sad to be away from them… (nurse, female, 27 years old).

I didn’t see my child for a long time. My wife surprised our child so that he could see me. When I got back home, I couldn’t hug my child, who came running to hug me. The fear of ‘what if it is transmitted’, I cannot find words to describe what I felt at that moment… (nurse, male, 30 years old). This nurse, who was a father, was tearful while describing these feelings.

Longing for pre‐epidemic days

Nurses missed spending time with their children and playing with them because of the fear of transmitting the virus. This situation was causing them to experience sadness.

I have two children, both at a playful age. They are very fond of me; we played ball together before the epidemic. I told them tales, and we slept together…Now I can’t do any of these things…I miss hugging them (nurse, male, 36 years old).

I sent my children to the village near my mum. I miss them so much. The weird silence of their absence in the home hurts me. The house is a like a funeral home—cold, cheerless (nurse, woman, 38 years old).

Fear

The nurses who participated in the study were living in fear of transmitting COVID‐19 to their children and other relatives at home. This caused them to isolate themselves from their children and other family members.

Fear of transmitting the disease

I realize that I am getting away from my children gradually. The fear of transmitting to them and that they will die is keeping me busy. I am very nervous. I get angry suddenly; I overreact (nurse, female, 34 years old).

I am very afraid of transmitting the virus to my wife and children. The thought of ‘what if it is transmitted despite the measures I take’ wears me down. It is very scary to think about being separated from your loved ones… (nurse, male, 38 years old).

In the past, my children would run to hug me when I came home from work. Now they cannot leave their room when I come home from work. They look at me with fear. They don’t want me to go to work; they think that I’ll die…My daughter wants me to promise to take care of myself while going to work every day; she wants me to resign… (nurse, female, 33 years old).

The expressions of a nurse who has a baby: “I am undecided about whether I should breastfeed my child because of the fear that I might transmit the disease; I am very confused” (nurse, female, 30 years old).

I am not sure about how to protect my family from the virus. It is not possible to be completely isolated. This causes some obsessions. I love my children from far away, and this makes both me and my children sad (nurse, male, 27 years old).

Fear of death

Nurses feared the death of their children and other loved ones due to the COVID‐19 epidemic. Their children were also concerned that their parent might die.

The expressions of a nurse: “…my older son saw people who died due to the epidemic on TV. He asked me, ‘Mum, I am very scared that you will die if you get infected; you won’t die, will you?’ I felt very bad when I heard this; his worry and fear made me very worried” …(nurse, female, 30 years old).

Another nurse providing care to COVID‐19 patients: “I am not scared for myself; I will continue to work as much as I can. However, as a mother, I am scared of my husband and children getting sick and dying…” (nurse, female, 26 years old).

Despair

Nurses were helping patients and providing them with care. They were thinking that they could not do anything for their children while they were doing something for others.

During this process, I think that I have to provide care to patients who need me. On the other hand, I think about my children. They need me too. Then I feel guilty and desperate (nurse, female, 25 years old).

My children said ‘Mum, other kids are staying home with their mothers. You are not staying with us; we are bored at home’. I feel very guilty when they speak like this… (nurse, female, 27 years old).

The expressions of a nurse whose spouse is also a nurse: “We are both away from our children. Like the family is scattered…We sent our children to a village near my mum. When my children first went there, they were happy that they could walk around freely. However, as time went by, they wanted to return home and stay with us. We explained to them that this wasn’t possible. They were very sad and they cried; I felt despair, like I left them there…” (nurse, female, 38 years old).

Concern

Concerns about working in a different clinic

The hospitals’ administration teams assigned a large number of nurses to provide care to COVID‐19 patients. The COVID‐19 clinic was a foreign environment for these nurses.

The expressions of a nurse: “I am working in this clinic for the first time. The devices, nurses, environment, everything is so different. I am a foreigner to everything. I feel like I haven’t worked in this hospital before…I don’t know the health team; I don’t know the organization of this new clinic. My working routine changed. These things are increasing my concerns” (nurse, female, 42 years old).

Concerns about lack of knowledge

Nurses stated that they felt concern about many things during the epidemic, including issues such as the quick transmission of novel coronavirus and its deadly results, difficulties providing sufficient care to COVID‐19 patients, and the lack of equipment.

The expressions of a nurse: “There was a lack of equipment when the COVID‐19 service was first opened. Besides, it was a new epidemic. I was worried about many things. I had concerns about how to approach the patients and that I might not provide them sufficient care…” (nurse, female, 37 years old).

A nurse described her lack of knowledge about the COVID‐19 epidemic as follows: “…The training given in the hospital did not have the expected quality and content. We were under informed by infection nurses about the order of wearing and taking off protective equipment and the use of masks. The infectious diseases physician held a question‐and‐answer meeting in front of the hospital elevators. I don’t know if this is sufficient” (nurse, female, 38 years old).

Hospital administration did not give us comprehensive training. Lack of knowledge increases my concerns. What if I can’t provide sufficient care, or what if my patient does not recover…This is too bad…When I go to the hospital to work, I pray ‘God, I hope no one dies’ (nurse, female, 33 years old).

Concerns about lack of equipment

Nurses stated that at the beginning of the epidemic, they were not given enough protective equipment; thus, they experienced concerns about being infected with COVID‐19.

The expressions of a nurse: “The supply of equipment was late and limited. During this process, I was very worried while providing care to patients…” (nurse, female, 38 years old).

Professional responsibility

Professional awareness

The nurses who participated in the study were providing care to patients by risking their own health during the COVID‐19 epidemic. However, despite this risk, none of them considered quitting their profession.

The expressions of a nurse: “I am a healthcare professional. My patients’ health is very important for me. I cannot let down people who need me” (nurse, female, 29 years old).

We face a major epidemic. We are doing important things in this epidemic. We’re like soldiers on the forefront of a war. I am happy to do my job in this epidemic (nurse, female, 26 years old).

It was proven once more how important and valuable healthcare professionals are, that they suffer the most and work in all conditions without any hesitations (nurse, female, 32 years old).

Love for the profession

I never thought about quitting the job in such an epidemic. For me, it will be unethical to quit in these difficult days. In addition, I love my profession very much. I am so happy that I became a nurse (nurse, female, 42 years old).

…my child says that I am a hero. Helping my patients to recover made my child think that I became a hero. I am proud of my profession and myself too (nurse, female, 30 years old).

Our people are aware of what we are doing; they appreciate us. Our president and our minister of health thank us. This increases our motivation to work (nurse, female, 35 years old).

I cannot describe the happiness that I feel when a COVID‐19 patient recovers and is discharged from intensive care. At that moment, I say I am glad that I became a nurse (nurse, female, 38 years old).

Discussion

This aim of this study was to examine the experiences and feelings of parent nurses who care for COVID‐19 patients. Healthcare professionals spend more time with patients who are infected with COVID‐19 in order to provide them with treatment and care. For this reason, nurses have a higher risk of being infected with COVID‐19 (Lai et al. 2020; Mo et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020). In our study, the nurses stated that they experienced the fear of transmitting the infection to their children, and for this reason, they had to leave them with their relatives. They also stated that they felt guilty for being away from their children, and they missed the days they had spent time together. They stated that their children also missed them; they were worried about them and wanted to play with them.

There is a very special bond between a parent and a child. The parent is the most important person a child trusts (Öngider 2013). Children need to build emotional intimacy with their parents, as well as a sense of safety and security. Not seeing one’s parents for a long time can create a sense of abandonment and decrease a child’s sense of confidence, especially in young children (Öngider 2011). Many parents also want to establish a close, sincere relationship with their children (Öngider 2011; Öngider 2013). During the pandemic, nurses’ separation from their children has caused them to experience longing, anxiety, and desperation. In their study, Sun et al. stated that nurses who provided care for COVID‐19 patients were worried about being separated from their children (Sun et al. 2020). During COVID‐19, nurses all over the world worked longer than usual and sometimes without enough protective equipment (Harrington et al. 2020; Jiang et al. 2020; Kim 2018; Nemati et al. 2020). Some nurses got ill due to and unfortunately some lost their lives (Pala & Metintaş 2020). ICN reported that 1500 nurses in 44 countries and globally more than 20 0000 healthcare professionals lost their lives and more than four million healthcare professionals got infected due to COVID‐19 (ICN 2020). In our country, Ministry of Health reported that 29 865 healthcare professionals got infected and 85 of these lost their lives (Republıc of Turkey Mınıstry of Health 2020a, 2020b). In addition, nurses saw the death of some of the patients they cared for in the intensive care (Pala & Metintaş 2020). World Health Organization reported the number of patients who died due to COVID‐19 as 1 416 292. Rapid transmission and deadly consequences of COVID‐19 cause nurses to feel desperate, pain, and physical and mental burnout (Sun et al. 2020). Nurses can isolate themselves more from their children and their loved ones in case the possibility of contagion. This situation may have a negative effect on parent nurses and their children (Mo et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020).

In this study, nurses working in the pandemic service reported that they experienced the fear of being infected/infecting others with the disease due to the increase in the number of cases and the lack of treatment and protective equipment (Jiang et al. 2020; Kim 2018; Nemati et al. 2020). For this reason, the nurses stated that they experienced the fear of transmitting the infection to their children and relatives and causing their deaths. They also stated that their children were afraid that their parents could die. In their study, Bukhari et al. found that nurses working during the MERS‐CoV experienced the fear of transmitting the disease (Bukhari et al. 2016). In their study, Maunder et al. also reported that the nurses working during the SARS experienced the fear of transmitting the disease (Maunder et al. 2003). Because COVID‐19 is transmitted quickly from person to person, threatens human life, and has many unknown characteristics, it can cause nurses to experience fear (Cao et al. 2020).

Hospitals have implemented policies to fight the COVID‐19 epidemic. They have opened COVID‐19 services and begun to treat patients. The need for nurses working in these services has increased (Kim 2018; Sun et al. 2020). Nurses who previously worked in different units have begun working in COVID‐19 services. However, negative feelings—such as physical burnout, lack of information, feeling alienated, fear, anxiety, and desperation—can develop in nurses working in these services (Cai et al. 2020; Khalid et al. 2016; Kim 2018; Mo et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020). In our study, some of the nurses stated that they had difficulty getting used to their colleagues and the environment as a result of changing their services. Changes in the delivery of patient care, personal protective equipment and devices, and environment have caused anxiety in nurses. In addition, in this study, the nurses stated that they were not sufficiently trained about COVID‐19; they felt unable to adequately care for their patients, and they were afraid that their patients might die. Some nurses have stated that having insufficient protective equipment at the beginning of the epidemic caused them to be infected with COVID‐19. Similarly, Sun et al. found that nurses felt alienated and were worried while working in COVID‐19 services (Sun et al. 2020). Nemati et al. found that nurses’ knowledge of COVID‐19 was almost good; however, they also stated that WHO and the minister of health should provide more information (Nemati et al. 2020). The increased workload of nurses, lack of protective equipment, and the feeling of being supported insufficiently while fighting the epidemic can cause them to experience negative feelings, such as anxiety (Chua et al. 2004; Lai et al. 2020; Maunder et al. 2003).

Nurses’ fighting on the forefront, especially those who are parents, can experience negative effects physically, psychologically, and emotionally (Bukhari et al. 2016; Lai et al. 2020). In our study, the nurses stated that their children felt sad when they left their children at home or with their relatives while they went to the hospital to care for COVID‐19 patients, and this in turn caused them to feel helpless. Children always need their parents’ attention, love, and support. They feel happy and safe when they are with their parents and when they do activities (playing, reading, going to the park) with their parents. The interactions between the parent and the child shape the child’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and values. However, an interruption in this relationship, even for a short time, can have a negative effect on the interactions between the child and the parent (Dereli & Dereli 2017). Because epidemics cause nurses to work for a long time in the hospital and to be separated from their children, nurses can experience feelings of helplessness during these times.

While nurses are struggling with the COVID‐19 pandemic, cooperation among healthcare professionals, motivation, the wish to fight together, and the support of the hospital administration, patients, family members, the state, and social groups play an important role in strengthening nurse resilience (Hui et al. 2020; Khalid et al. 2016; Lai et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2020). In our study, the nurses stated that they loved their profession, they were proud of themselves for working in this profession, they were aware of their professional responsibility, and they did not think about resigning. In addition, they stated that they were happy about the appreciation of state authorities, the minister of health, and the citizens.

They also stated that their children telling them that they were heroes motivated them. They said that they shared their patients’ happiness when they recovered and were discharged. They believe that we can overcome this difficult process through unity and solidarity. In Kim’s study, it was found that nurses’ resilience increases when they think about the patients they must provide care for (Kim 2018). In their study, Khalid et al. stated that healthcare professionals were aware of their professional ethical responsibilities and that the hospital administration supported them so that it was easier for them to remain in their profession (Khalid et al. 2016).

Limitations

The COVID‐19 pandemic requires strict isolation precautions. For this reason, we could not have face‐to‐face interviews with the nurses. The data discussed in this study were obtained through email, which caused various limitations, including not being able to observe the tone of voice and gestures of the participants and not being able to ask follow‐up questions encouraging them to express their opinions (e.g., “What exactly did you mean? Can you elaborate?”) that could have provided more in‐depth information.

Implications for nursing and health policy

The data obtained from the results of the present study are also supported by the literature. Nurses working in COVID‐19 services separate from their children to avoid infecting them. This situation has a particularly negative effect on children. Children miss their parents and want to spend time with them. In order to minimize the longing between children and parents, nurses should be placed on rotations in and out of COVID‐19 services. Institutions should increase the number of nurses; nurses working on the periphery should be made to work in large central hospitals. In addition, nurses’ workload should be reduced, and they should be given the opportunity to go to the hospital less by working in shifts. Hospital administrators can organize activities to strengthen nurses psychologically. Nurses should be given up‐to‐date information about COVID‐19 through regular training programs.

COVID‐19 is a major pandemic, and it has caused the deaths of a large number of people. It can be seen that nurses who fight on the forefront in the struggle with such a pandemic love their job and do their best in accordance with their professional ethics. For this reason, the struggle of nurses should be recognized, supported, and rewarded by the state.

Conclusion

In the present study, which examined the experiences and feelings of parent nurses who provided care for COVID‐19 patients, it was found that nurses missed spending time with their children and the pre‐pandemic period. In addition, they were afraid of transmitting the disease to their children and family members, and their children were also worried about their parents. The nurses experienced desperation; however, they loved their profession, and they were aware of their professional responsibilities.

Author contributions

Study design: DCŞ, UG

Data collection: DCŞ

Data analysis: DCŞ, UG

Study supervision: UG

Manuscript writing: DCŞ, UG

Critical revisions for important intellectual content: DCŞ, UG.

Acknowledgment

The authors sincerely thank the nurses.

Coşkun Şimşek D.& Günay U. (2021) Experiences of nurses who have children when caring for COVID‐19 patients. Int. Nurs. Rev. 68, 219–227

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Funding source: None.

References

- Arabacı, Z. , Hasgül, E. & Serpen, A. (2016) Mıgrant women and mıgratıon’s effect on women’s health ın Turkey. Sosyal Politika Çalışmaları Dergisi, 36, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, D. , Şahin, N. & Akay, B. (2017) Effects of immigration on children’s health. İzmir Dr. Behçet Uz Çocuk Hastanesi Dergisi, 7 (1), 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.K. , et al. (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395 (1022), 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari, E.E. , et al. (2016) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) outbreak perceptions of risk and stress evaluation in nurses. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 10 (08), 845–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H. , et al. (2020) Psychological ımpact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in hunan between january and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Hubei, China. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 26, e924171–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W. , et al. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q. , et al. (2020) Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID‐19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7 (4), e15–e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua, S.E. , et al. (2004) Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high‐risk health care workers. The Canada Journal of Psychiatry, 49 (6), 391–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereli, E. & Dereli, B.M. (2017) The Prediction of parent‐ child relationship on psychosocial development in preschool children. Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 14 (1), 227–258. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H. & Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24 (2), 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacıhasanoğlu, A.R. & Yıldırım, A. (2018) Social and Mental Effects of Immigration and Nursing. İstanbul: Türkiye Klinikleri; 10–20. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12432/2788 [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, C. , et al. (2020) Nurse staffing and coronavirus infections in California nursing homes. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 21 (3), 174–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui, D.S. , et al. (2020) The continuing 2019‐nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 91, 264–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses . (2020) ICN confirms 1,500 nurses have died from COVID‐19 in 44. Available at: www.icn.ch › news › icn‐confirms‐1500‐nurses‐have‐die. (Accessed 27 November 2020).

- Jiang, N. , Jia, X. , Qiu, Z. , Hu, Y. , Jiang, T. , Yang, F. , & He, Y. (2020) The influence of efficacy beliefs on interpersonal loneliness among front‐line healthcare workers during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in china: a cross‐sectional study. Available at SSRN 3552645, 10.2139/ssrn.3552645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, W.Y. , et al. (2020) Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID‐19 epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics, 221, 264–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, I. , et al. (2016) Healthcare worker semotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during MERS‐CoV outbreak. Clinical Medicine & Research, 14 (1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. (2018) Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control, 46 (7), 781–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Sefcik, J.S. & Bradway, C. (2017) Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 40 (1), 23–42. 10.1002/nur.21768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J. , et al. (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA network open, 3 (3), e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, R. , et al. (2003) The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ, 168 (10), 1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y. , et al. (2020) Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID‐19 epidemic. Journal of Nursing Management, 28 (5), 1002–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, M. , Ebrahimi, B. & Nemati, F. (2020) Assessment of Iranian nurses’ knowledge and anxiety toward COVID‐19 during the current outbreak in Iran. Archives of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 15, e102848. [Google Scholar]

- Öngider, N. (2011) Investigation of Anxiety Levels in Divorced and Married Mothers and Their Children. Nöropsikiyatri Arşivii, 48, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Öngider, N. (2013) Relationship between parents and preschool children. Current Approaches in Psychiatry/Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar, 5 (4), 420. [Google Scholar]

- Pala, S.Ç. & Metintaş, S. (2020) Healthcare professıonals ın the COVID‐19 pandemıc. ESTÜDAM Halk Sağlığı Dergisi, 5, 156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. (2005) Qualitative research. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science, 3, 1633–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Republıc of Turkey Mınıstry of Health (2020. a). Covıd‐19 Informatıon Page. Turkey. Available at: https://covid19bilgi.saglik.gov.tr/tr/sss/halka‐yonelik.html. (Accessed 01 July 2020).

- Republıc of Turkey Ministry of Health (2020. b). COVID‐19 (SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection) General Information, Epidemiology and Diagnosis. Turkey. Available at: covid19.saglıi.gv.tr. (Accessed 29 June 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , et al. (2020) Knowledge and attitudes of medical staff in Chinese psychiatric hospitals regarding COVID‐19. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity‐Health, 4, 100064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.W. , Smith, P.W. , Kratochvil, C.J. & Schwedhelm, S. (2017) The psychosocial challenges of caring for patients with Ebola virus disease. Health Security, 15, 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N. , et al. (2020) A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID‐19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48 (6), 592–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam, C.L. , Lee, T.H. , Kumarasuriar, V. & Har, W.M. (2012) Parental authority, parent‐child relationship and gender differences: A study of college students in the Malaysian context. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 6 (2), 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020a). Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic. Available at: https://www.who.int/healthtopics/coronavirus#tab=tab. (Accessed: 01 July 2020). [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020b) Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Dashboard. Turkey. Available at: https://covid19.who.int. (Accessed: 27 November 2020). [Google Scholar]