Abstract

This article documents and compares the social policies that the governments in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) implemented to combat the first wave of COVID‐19 pandemic by focusing on Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia. Our findings show that governments in all four countries reacted to the COVID‐19 crisis by providing extensive protection for jobs and enterprises. Differences arise when it comes to solidaristic policy responses to care for the most vulnerable population, in which CEE countries show great variation. We find that social policy responses to the first wave of COVID‐19 have largely depended on precious social policy trajectories as well as the political situation of the country during the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID‐19, crisis, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, social policy

1. INTRODUCTION

This article describes and compares the policies implemented in four Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries during the first wave of pandemic which started in March and lasted until the end of August 2020. More specifically, it draws attention to the social policy measures implemented during the COVID‐19 crisis in Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia. These countries were chosen to represent as much as possible the variety of countries and policies in the CEE region. Hungary has one of the lowest levels of income inequality in the region, Poland and Slovakia are in the middle, while Lithuania has one of the highest levels (Aidukaite, 2011, 2019; Bohle & Greskovits, 2007; Lendvai, 2008).

This study asks the questions: What social policy measures were implemented to mitigate the socio‐economic crisis stemming from the COVID‐19 pandemic in the countries under investigation? What new social policy agendas have emerged from the crisis? What could be the long‐term implications of the crisis for the welfare state in these countries? We apply descriptive research to identify social policy measures implemented and utilize the path‐dependency thesis of Chung and Thewissen (2011) to explain social policy responses to the crisis situation. The situation of the four countries is analysed and compared by utilizing the OECD data, national statistical data sources, newspaper articles and national policy documents.

First, we review the key aspects of the CEE welfare state and differences among the four countries under investigation, as well as differences in the situation of the health aspects of COVID‐19. Second, we review social policy responses towards the COVID‐19 crisis during the first wave of pandemics in Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia. Then, we conduct a comparative discussion and provide the major findings.

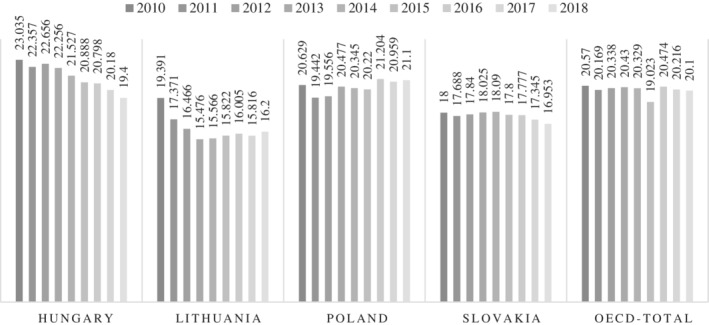

2. FROM THE PANDEMIC TO THE ECONOMIC CRISIS

Not much has been written about how crises influence social policies. Writing about the 2008 financial crisis, Chung and Thewissen (2011) emphasize path dependency and claim that European countries basically implemented temporary measures that were in line with what type of welfare regime to which they belonged. Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia in a broader sense fall under the so‐called post‐communist or Eastern European welfare state model. This ideal‐typical model mixes characteristics from both the liberal and conservative‐corporatist regimes as well as including some distinct features of the post‐communist societies. Namely, these countries have inherited from the state‐socialist era a high take‐up rate of social security but relatively low benefit levels. They also share a commitment to social insurance, combined with elements of universalism, corporatism and egalitarianism (Aidukaite, 2011; Cerami, 2006; Cerami & Vanhuysse, 2009; Deacon, 1992; Haggard & Kaufman, 2008; Szikra & Tomka, 2009). Recent literature (Jahn, 2017; Jahn & Kuitto, 2011; Kuitto, 2016) that focuses on social policy performance in CEE countries (often in comparison with Western ones) concludes that the CEE countries do not form their own welfare state regime type. Instead, they are considered to be either hybrid cases (Kuitto, 2016) or fall into different regimes (Jahn, 2017). Studies also point to significant differences among the CEE countries (Aidukaite, 2019; Bohle & Greskovits, 2007; Kuitto, 2016; Lendvai, 2008). Diversity can be observed in spending patterns, with Slovenia, Hungary and the Czech Republic being higher social spenders in terms of percentage of GDP than the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria, with Poland being in the middle. Social spending as per cent of GDP (see Figure 1) underpins patterns discussed above. Higher spending in Hungary and Poland compared to the other two countries is notable despite the fact that the former country has shown a steady decline in social spending during the period of 2010–2018. In terms of disaggregated welfare spending, the most important similarity is that all four countries have a pension‐heavy welfare state with around 40% of their social spending going to this purpose (OECD, 2020). Hungary can also be characterized as a high spender on family policies with greater investment in child care services and longer periods of parental leaves that are based on the income replacement principle (Rat & Szikra, 2018), while Slovakia bases its system more on long parental leaves with flat rate benefits (Saxonberg, 2014); meanwhile, Poland recently switched from having more market‐oriented policies to a system with greater investment in child care services and longer period for parental leaves, as well as generous universal payments (Szelewa, 2017). Lithuania is the country with the most defamilalizing parental leave policies and is generous in replacement rates and duration of leaves (Javornik, 2014; Javornik & Kurowska, 2017). Social policies vary in other areas as well, for example, in the extent in which they reduce inequality and poverty. Baltic states have high levels of income inequality and poverty, while Poland, Hungary and Slovakia are in the middle group with average levels of poverty and inequality. The Czech Republic and Slovenia show high levels of welfare efforts and low levels of poverty and inequality.

FIGURE 1.

Social spending, public, per cent of GDP. Source: OECD, 2020

Of particular importance for handling the pandemic is that all four countries have publicly financed health care systems with near universal coverage (Aidukaite, Moskvina, & Skuciene, 2016; Orosz, 2018). Also, inherited from the state socialist times, public health systems secure compulsory vaccination of the entire population against the most dangerous contagious diseases, including the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis that has been proposed as a way to reduce the severity of COVID‐19 (Escobar et al., 2020).

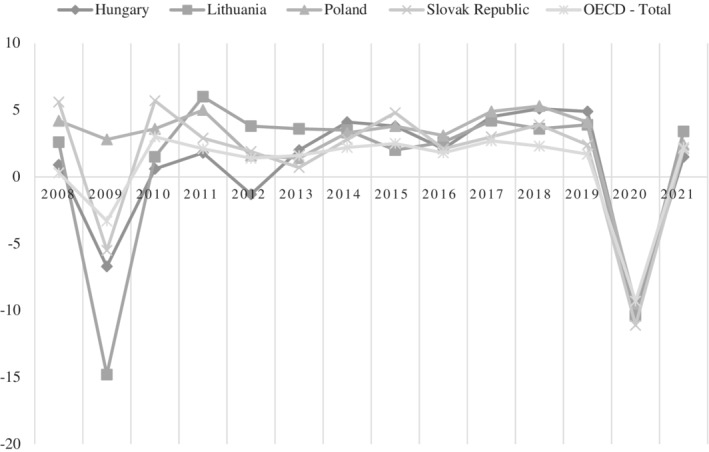

CEE welfare states have been under heavy pressure following the financial and economic crisis of 2008–2010 (see Aidukaite, 2019; Saxonberg & Sirovátka, 2014; Szelewa, 2014; Szikra, 2014). The pressure was felt most severely in Lithuania, where cuts in social benefits and public wages were implemented in order to reduce government budget deficits as also indicated by Figure 1 (Aidukaite, 2019). Slovakia and Hungary have also suffered a decline in GDP, while Poland has managed to retain the same level of GDP during the crisis. As illustrated by Figure 2, all four countries have managed to overcome the crisis and have experienced fast growth in their GDPs since 2010. The yearly forecast for 2020 projects GDP to fall; however, in 2021, it is expected to rapidly increase in all four countries.

FIGURE 2.

Real GDP forecast, double‐hit scenario, annual growth rate (%), Annual, 2008–2019, %. Source: OECD, 2020

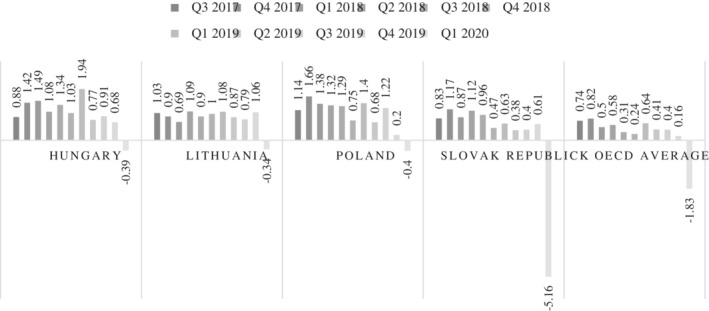

The latest available data on the quarterly GDP change show that the COVID‐19 crisis has already caused the economy to decline as all four countries experienced a decrease in GDP during the first quarter of 2020 (see Figure 3). However, the decline for Hungary (−0.39%), Lithuania (−0.34%) and Poland (−0.4%) is lower than the OECD average which is −1.83%. Slovakia has experienced the steepest decline of −5.16%.

FIGURE 3.

Quarterly GDP total, percentage change, previous period, Q3 2017–Q1 2020. Source: OECD, 2020

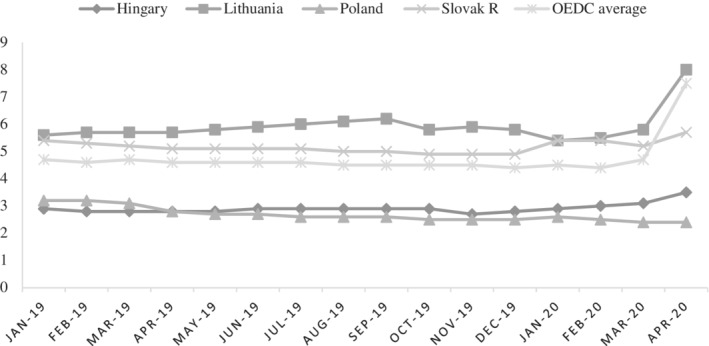

All countries have suffered an increase in unemployment as per cent of total labour force during the financial and economic crisis of 2008. According to the OECD data (2020), the increase was higher in Lithuania than in the other three countries under investigation as it jumped from about 4% in 2008 to almost 18% in 2010. A notable increase of unemployment could also be observed in Slovakia – from about 9% to 15%. In 2012–2013, the unemployment rate started to decline in all four countries, so by the end of 2019, it fell to 3.4% in Hungary, 6.4% in Lithuania, 2.9% in Poland and 5.6% in Slovakia. Following the outbreak of the pandemic, unemployment started to increase again, and, by May 2020, it reached 4.1% in Hungary, 9.3% in Lithuania, 3% in Poland and 6.5% and in Slovakia. Related data suggest that initially Lithuania had the highest unemployment rate, further increasing during the health crisis.

OECD (2020) data shows that youth (15‐ to 24‐year‐olds) have higher unemployment rates in all four countries than 25‐ to 75‐year‐olds. During 2020, unemployment increased for all age groups in the four countries – especially since March, when governments of these countries undertook lockdown measures (see Figure 4). As Lithuania and Slovakia initially had higher unemployment rates than Hungary and Poland, they also show higher rates of unemployment for all age groups. The unemployment rate is expected to rise faster in those countries (especially Lithuania), where it increased most during the financial crisis as their economies seem to be more exposed to external shocks. The situation is best in Poland, as it shows only a slight increase in unemployment rate for the group of 15‐ to 24‐year‐olds and even decline for the age group of 25‐ to 75‐year‐olds.

FIGURE 4.

Unemployment rate by age group 25‐ to 75‐year‐olds, per cent of labour force. Source: OECD, 2020

All four countries under investigation have neglected the area of (active) labour market policies, and some of them even cut back on such policies during the 2009 global economic crisis. Poland did not increase benefit levels, while Hungary cut both the length and the nominal value of unemployment‐related social benefits. Hungary also adopted an overarching, compulsory public works program (Molnár, Bazsalya, Bódis, & Kálmán, 2019). Slovakia implemented a workfare scheme of public service ‘activation’ jobs during 2000s, although not as a reaction to the global crisis (Saxonberg & Sirovatka, 2019). In Lithuania, due to a dramatic increase in unemployment in 2009, the unemployment insurance benefits were reduced temporarily (Aidukaite et al., 2016). This situation would suggest that Eastern European countries, when facing yet another economic downfall following the COVID‐19 pandemic, would not do much to cater to the unemployed via direct social subsidies or training and retraining programs. However, our study shows significant variation among CEE countries in terms of handling mass unemployment and economic inactivity under the first wave of pandemic.

Our World in Data (2020) on the number of COVID‐19 cases suggests that all four countries had experienced a relatively low number of cases per million inhabitants until September 2020, compared to Western or Southern Europe. In Hungary, Lithuania and Slovakia, 0.1–2% of tests proved positive. In Poland, the situation was worse, but positive cases still did not exceed 2–3% of all tests. As we will show in the forthcoming discussion of country‐cases, the common distinctive feature of CEE countries' response to COVID‐19 was that they went on lockdown in March 2020 despite the low case numbers. Early response may have contributed to keeping positive cases low.

3. POLICY RESPONSES

3.1. Hungary

The Hungarian government reacted promptly to the COVID‐19 pandemic and declared a State of Emergency (Veszélyhelyzet) on 11 March that allowed the government to rule by decree. Educational institutions were closed, border checks were re‐instated and travel from the most affected European regions was restricted. Lockdown measures included restricted opening times of most shops, cultural and sport facilities, the complete closure of restaurants, limited opening times of all shops and a ban on gathering. A special time zone was designated for the elderly between 9 a.m. and 12 a.m. to do their daily shopping. The government eased the lockdown measures in the countryside at the end of April and in Budapest from May 18, while the State of Emergency was withdrawn on June 16. Hungary, a country of 9.7 million, registered altogether 4,448 infected cases (460.44 per million inhabitants) and 596 death caused by the COVID‐19 virus by July 28, 2020. According to the forecast of the European Commission Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (2020), the country will survive the pandemic with a 7% drop of GDP in 2020, followed by a quick recovery in 2021 with a 6% increase.

The social policy responses which the government undertook concentrated primarily on protecting jobs and suspending loan and tax payments. Family and housing policy measures also eased the burden of the population. In contrast to the wide range of fiscal policies adopted under the pandemic, cash transfers to the most vulnerable, unemployed population were neglected areas.

As a major means of job protection, employers were allowed to deviate from the Labour Code. According to trade unions and experts, some of these changes may have dismantled workers' rights (Gyulavári, 2020). Apart from increasing the flexibility of working conditions, the Hungarian version of the German ‘Kurzarbeit’ was adopted. Accordingly, a state subsidy of up to 70% of wages can be provided until the end of August to companies that employ workers part‐time. Another program, issued in mid‐May, provided a state subsidy for up to 9 months at 100% of wages to companies employing registered unemployed. As of July 28, 2020, some 200 thousand employees were said to have benefitted from these programmes.

A payment moratorium for business taxes for all companies was also issued. Meanwhile, rental contracts for businesses in catering, entertainment, tourism and passenger transport were protected until at least the end of June. These sectors were also relieved from social insurance contributions and certain taxes. A new interest‐free loan for students was also introduced.

Due to the COVID‐19 crisis, the unemployment rate rose to 8.1% by June 2020. While larger companies could utilize the Kurzarbeit scheme, a sizable share of small enterprises had to lay off workers or cease their businesses due to the lockdown. In their case, the state was not as generous as with companies to keep jobs. The length of the unemployed insurance benefit remained maximum of 3 months, and the benefit level kept at 70% of the minimum wage. Workers who were laid off by their employers and became registered unemployed under the pandemic received no special protection or social assistance. The loopholes of the Hungarian unemployment benefit system already existed prior to the 2020 crisis but now affected a larger size of the population. National data show that close to half of all registered unemployed received no benefit from the state because they did not fit the strict eligibility criteria (Nemzeti Foglalkoztatási Szolgálat – NFSZ, 2020). A similarly sizable population was left out of the unemployment benefit schemes due to being formerly employed in the black or grey economy, and these people received no social protection from the state at all, be that universal or targeted benefits. The neglect of the unemployment benefit scheme reflected the ideology of the ruling party about a ‘work‐based society’ that claims that no handouts should be provided to the workless (Köllő, 2019; Szikra, 2019). In line with this social policy paradigm, the public works programme was extended providing simple physical work to some of the unemployed (Molnár et al., 2019).

Local governments, who were badly effected by cuts of their budgets under the COVID‐19 crisis, provided daily meals for children enrolled in child care institutions or schools, as well as for needy adults during the lockdown period. Furthermore, the Ministry of Interior organized charitable donations of food and sanitary products. Notwithstanding in kind social assistance, the lack of a minimum income guarantee scheme in Hungary has proven to be a major pitfall under the crisis, leaving people without social insurance contributions with a complete lack of resources.

When it comes to health policies, primary care, outpatient institutions, hospitals and elderly homes were closed in mid‐March. Meanwhile, people were obliged to wear face masks and keep social distance both in shops and while taking public transportation. Insured employees who were either diagnosed with COVID‐19 or were obliged to quarantine received sickness insurance benefits according to previous rules. The benefits paid a maximum of 60% of previous wages capped at the net minimum wage. Health care staff received an extra, one‐time payment of 500 thousand HUF gross. An arrangement in early April that obliged hospitals to decrease their capacities by 60% caused a public outcry as it put an unbearable burden on many sick people and their families.

Concerning families with children, all maternity and parental leave payments as well as family allowances that would have expired during the period of the lockdown were extended for the total duration of the state of emergency. The administrative steps for applying for loans and subsidies issued as part of the 2019 Family Protection Action Plan were eased and/or extended. Starting from 1 July, state subsidies to gain language exams or driving licences were adopted for parents on maternity or parental leaves in the form of one‐time payments worth 40.250 and 25.000 HUF (app. 116 and 72 EUR, respectively). In the field of pensions, an extra one‐time payment in January, 2021, was announced, worth a weekly amount of each pensioner's benefit.

The Hungarian government was criticized for using the State of Emergency for politically and ideologically motivated measures under the first (and later also under the second) wave of the pandemic. The decrease in income of municipalities limited their possibilities to implement health‐related and social assistance measures during the crisis, while the decision to reject the ratification of the Istanbul Convention and to end the legal recognition of trans‐people went against gender equality and the rights of LGBT+ people.

3.2. Lithuania

The Lithuanian government took early preventive COVID‐19 measures by closing schools, preschools and nurseries from March 14. In addition, stores (except food stores), all cultural activities, services, restaurants, bars and cafes were closed from March 14. Everyone was advised to work from home. Meanwhile, schools and universities switched to online teaching. Any gatherings were forbidden, and face masks were made obligatory. These lockdown measures were prolonged until May. On May 10, the Lithuanian government started to ease the quarantine measures, and on 16 June, the quarantine was cancelled. The country with a total population less than 2,7 million inhabitants endured 80 deaths from COVID‐19 by July 28, with the total number of infected reaching 2,027 (Worldometer, 2020). According to Our World in Data (2020), on August 4, there were 3.63 cases per million persons. The summer forecast of the European Commission Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (2020) has drawn a rather optimistic scenario for the Lithuanian economy suggesting that it would shrink due to the COVID‐19 crisis by 7% and recover already in 2021 and grow by 5.9%.

The social policy responses taken by the Lithuanian government can be divided into quarantine and post‐quarantine measures. The policy responses during the quarantine were aimed at saving jobs and the income of the population, as well as helping businesses to maintain liquidity. Yet, the major bulk of the measures were aimed at ensuring the successful operation of the health care system.

In order to protect jobs and income, the government contributed jointly with employers to cover up to 3 months of the downtime allowance for the employees set at the minimum monthly wage (EUR 607). To protect the self‐employed, the government issued a benefit of 257 Euros for up to 3 months (EL, 2020; Social‐demokratai, 2020).

In the field of family policy, working parents (taking care of children up to 14 years, disabled children up to 21 years' old, elderly people) were allowed to take sick leave for 14 days, to be prolonged up to 60 days, compensated at a replacement rate of 65.94%. Employers were obliged to ensure the possibility of flexible working conditions, including home office. Mortgage loans were postponed for from 3 to 6 months for those employees/self‐employed who lost their job during the quarantine. In order to maintain business liquidity, the payment date of tax arrears was postponed (EL, 2020; Social‐demokratai, 2020).

The salaries of health care employees were increased by 15%, and the government ensured the stable financing of the health care sector without decreasing resources. Additional expenses for protective equipment for doctors were provided. Health care professionals, officials or other employees infected by COVID‐19 received a sickness benefit of 100% of their net pay (OECD, 2020).

Overall, the social protection measures taken during the quarantine showed clear signs of solidarity. Data presented by the Lithuanian Ministry of Social Security and Labour (LMSSL) (2020) show that most of the self‐employed who applied for it received the fixed benefit of 257 Euros per month (84 thousand persons), and the total amount paid was EUR 53.535 million. More than 128 million Euros were paid in subsidies during the downtime and more than 2 million Euros after the downtime. Nearly all companies who applied for subsidies received them during the quarantine. The post‐quarantine measures in July were aimed further to support business and income of the population, as well as to help return back to the labour market.

Subsidies for employers to pay wages of their employees have been prolonged for additional 6 months after the end of quarantine and self‐employed people receive a benefit of 257 Euros for an extra 2 months after the quarantine (LMSSL, 2020). New measures were also taken in the area of employment protection policies and additional help to unemployed people. One‐time subsidies for a new job creation were approved to increase employment. These subsidies support enterprises/companies who want to employ the most vulnerable people such as those with disabilities, the youth and/or the elderly. The one‐time subsidy is also available to self‐employed people, who received an allowance of 257 Euros if they want to change their economic activity. A temporary job search allowance/benefit (200 Euros) was introduced for those who lost a job during the quarantine and is not entitled to unemployment insurance benefits. The new temporal benefit could be paid for a maximum of 6 months, but no later than until December 31, 2020 (LMSSL, 2020).

To protect the most vulnerable – the elderly, the disabled, orphans and widows – the government approved a one‐time lump sum benefit of 200 Euros. The post‐quarantine measures have also ensured that more families will receive higher child benefits (an additional 100 Euros per child), which is paid to low‐income families, large families with three or more children and families raising disabled children. The Seimas agreed that when assessing the income of a poor family, its income of the last 3 months will be taken into account, instead of 12. This means that the benefit will reach more children (LMSSL, 2020). Additionally, a one‐time lump sum of EUR 200 has been granted to each child from low‐income and large families, as well as children with disabilities, while all other children received EUR 120 (Lrytas, 2020).

All measures discussed above are temporal and aimed to support the employability and income of the most vulnerable inhabitants in the post‐quarantine period. The COVID‐19 crisis presented the opportunities also for a long‐term change in the social protection system. The government approved new measures in the social assistance field, which ensure higher protection for those with low incomes. The amount of monthly social assistance benefit was increased, and eligibility criteria were eased, namely, the asset test was cancelled and the financial eligibility threshold was reduced. Meanwhile, for low‐income families and single people, a greater share of their heating costs will be subsidized. All these measures will remain in force after the COVID‐19 crisis (except the income test, which will be revised to an assets test as soon as crisis ends) (LMSSL, 2020).

Lithuanian social policies have neglected housing (Aidukaite, 2014). The COVID‐19 crisis stimulated the debate and the need to address this important social policy field. Accordingly, access to social housing and related assistance has been improved. The waiting time for social housing has been shortened from 5 to 3 years. If at the end of the term, the municipality is not able to provide social housing for an individual or a family, then it has to reimburse the actual rental price of suitable housing rented on the market. At the same time, the minimum basic amount of compensation for the part of the housing rent was increased from 23 to 32 Euros per month per person, when the useful floor area per person or family member is 10–14 square meters. All these measures will remain in place after the pandemic ends (LMSSL, 2020).

Overall, the policy measures taken in the social protection field during the COVID‐19 crisis show clear signs of solidarity in Lithuania. In order to fulfil its commitments to these welfare reforms, the government has allocated money from the Social Insurance Fund, Guarantee Fund, the European Social Fund, as well as borrowings (LMSSL, 2020; EL, 2020; Social‐demokratai, 2020).

3.3. Poland

Within 8 days of diagnosing the first case of COVID‐19, the Polish government declared a state of emergency on March 12 (Prime Minister of Poland, 2020). Apart from closing the borders, the government introduced the obligation to wear masks in all public places; it started enforcing rules about social distancing and it closed all education/early education and care facilities. Among the countries in the region, Poland noted the highest number of cases per one million inhabitants, that is, 1,137.88.

In order to counteract the economic effects of the pandemic, as well as to respond to the public health crisis, the Polish government proposed a package of three legislative acts at the end of March, mid‐June and mid‐July. Social policy measures including employment protection became a crucial element of the legislative package labelled ‘Anti‐Crisis Shield,’ together with protecting the economic activities of companies, with 212 billion PLN (about 9.1% of GDP) spent on the former and 100 billion PLN (about 4.3% of GDP) on the latter (Government of Poland, 2020).

Employment protection measures became available to employers if they needed to halt their operations in relation to the COVID‐19 outbreak or if they were forced to shorten the working time. In the first case, employers had to demonstrate a decrease in sales and received compensation of all labour costs up to only 50% of the minimum wage (currently 2,600 PLN gross, around 590 EUR per month). A parallel scheme for small and medium companies links the level of support to the degree of loss in sales, covering up to 90% of all employment‐related costs in the case when loss in sales reached 80% (Government of Poland, 2020). Employers can receive this type of aid up to 3 month. When it comes to reducing working time, the state covers the cost of wages up to 40% of the average pay including social security dues for 3 months.

Furthermore, for self‐employed, a one‐off cash transfer of 80% of the average wage was made available. In case of a significant drop in activity, a one‐off cash payment of up to PLN 2080 (80% of minimum wage) for self‐employed and workers employed under civil law contracts was paid for up to 3 months.

The unemployed who have lost their jobs under the pandemic could receive a special solidarity scheme with a cash benefit of 1,400 PLN (about EUR 350) per month for a maximum of 3 months beginning June 1, 2020 (ZUS, 2020a). This unemployment compensation scheme provides a higher level payment than the regular one, that is, when unemployment is not caused by the pandemic (689 PLN ‐ 156 EUR). It increased first to 881 PLN (189 EUR) from 1 June and further to 1,200 PLN (272 EUR) from September 1, 2020 (Gazeta Prawna, 2019). Although the increase seems quite large, the level of the regular unemployment benefits in Poland was very low at 37% of one's previous (average) income (as compared to the OECD average of 64%) (OECD, 2019 in Naczyk, 2020).

Although it is too early to assess the overall effectiveness of the policy, survey data from June 2020 onwards show that unemployment has only marginally increased and stabilized at the level of 5.7% (compared to 5.5% in January 2020, GRAPE, 2020). At the same time, the level of state aid expressed in the percentage of wage coverage (40%) is smaller in comparison to other countries in the region (see e.g., the Hungarian case), as well as a great majority of the European countries, including the liberal welfare states, such as UK and Ireland, where state aid amounted to 75–80% of previous salary.

Similar to Hungary, some of the provisions that can be applied in case of a significant decrease of sales gave the employer the right to introduce less favourable working conditions (including worse working time arrangements, a simplified redundancy procedure or the immediate reduction of fringe benefits) than those guaranteed by the Labour Code or local agreements. In contrast to Hungary, however, the employer needs the consent of the trade unions to issue these measures (Eurofound, 2020).

The government also responded to the issue of the unforeseen increase in caring responsibilities among the families with children normally attending day‐care, pre‐school or the primary school. If a crèche, kids club, kindergarten or school closed, insured parents with children up to the age of 8 (or up to 18 in case of special educational needs) have been entitled to an additional care allowance for the whole period of closure at 80% of previous salary. A more recent family support measure includes a tourist voucher to cover the costs of staying at a tourist facility in Poland or organized by the company operating in Poland. Its value is 500 PLN (113 EUR) and is paid per child (ZUS, 2020b).

Furthermore, a sick leave allowance for people returning from abroad and their household members under quarantine was granted for employees and self‐employed at 80% of gross wages or average revenue.

Similar to other countries, monthly mortgage payments were suspended, but in Poland, the banks were free to set their own guidelines and conditions for obtaining such possibility. The deadline for submitting tax declarations was extended with an additional month both for companies and employees.

Finally, the pandemic coincided with the presidential elections in Poland. President Andrzej Duda of the Law and Justice Party got re‐elected, making it past the first round on June 28 and then winning the second round on July 12. Duda employed anti‐LGBT rhetoric during the campaign, while, similar to Hungary, the government plans to reject the ratification of the Istanbul Convention. Duda's success cemented the Law and Justice's right‐wing conservative political domination in the country.

3.4. Slovakia

The Slovak government took fast action against the COVID‐19 outbreak, even though in the first weeks, it had a care‐taker government that was only in place until the newly elected coalition could form a new government. The new cabinet that took office on March 21 continued the policies of the previous government. The economy fell by 3.7% in June 2020, and unemployment is expected to reach up to 9.5% (Financial report, 2020).

Shortly after the first case was reported, the government declared a state of emergency and the first measures came into force on March 12. By March 16, all the shopping malls, grocery stores, pharmacies and gas stations had to shut their doors. The government also banned all public events, closed its borders and airports and schools. During the Easter holidays from April 8 to 13, the government implemented a total lockdown, and people were not allowed to travel outside their home town (e.g., Kolenčík, 2020). Almost 80% of the population supported the government's actions (Gabrizova, 2020). The government started to eliminate these emergency measures step‐by‐step starting in late April. Even though the country has opened its borders and stores, most of the social policy measures adopted in this period will remain in place at least until September.

Slovakian politicians helped popularized the anti‐COVID measures by leading through example. As Böhmer () shows, already in February – 1 month before the first case was known in Slovakia – the then prime minister, Peter Pellegrini, began using the social media to warn the public about the virus and giving advice on how to avoid it. In addition, on March 14, he appeared publicly with members of his cabinet wearing a face mask, which popularized the notion that it is socially acceptable to wear them.

In order to protect jobs, the government decided to compensate 80% of the salaries for workers who work in companies that are mandatorily closed and to the self‐employed based on their decrease in revenues. Furthermore, 55% of the gross salaries to employers in quarantine and parents who are forced to stay home due to schools being closed were compensated. Thus, similar to Hungary, employers received compensation to keep their workers employed, which was financed by the central state budget and EU funds. Meanwhile, the social insurance scheme was somewhat extended to compensate employees who temporarily had to stay at home and be out of work. Social and health care tax payments of employers and income tax advance payments were temporarily suspended if revenues decreased by at least 40% (AS/Pol/Inf, 2020).

Employers and self‐employed employers who had to close their operations could apply for an employee's salary contribution of 80% of their average earnings, up to a maximum of EUR 1,100 per month under the condition that the employers maintain the job after the crisis period. The self‐employed could apply for compensation for their loss of income. In addition, employers (except public sector entities) whose sales had decreased could apply for an employee's salary allowance.

In the area of family policy, sickness and care allowances (to take care of a family member) were provided at about 70% of one's net wages for parents who had to take care of children, since the schools were closed (European Commission Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs, 2020).

For those who became sick because of the pandemic, the Social Insurance Agency starting paying sickness benefits from the first day of incapacity of work in the amount of 55% of the daily assessment base (AS/Pol/Inf, 2020). This marks an improvement of social rights compared to the previous situation when the employer paid for the first 10 days, and the employee only received 25% of the daily assessment base for the first 3 days (Slovensko.sk, 2020).

In order to alleviate the costs employers, the government postponed the deadline for paying social insurance contributions if the employers anticipated a 40% or more decline in economic activities until December 31 (Tomak, 2020). Some pensioners receive a pension in cash but, in the pandemic, were afraid to go to the post office, so the Social Insurance Agency made it possible to receive their pension via a family member (Pravda, 2020a).

The Ministry of Finance decided to assist micro‐, small‐ and medium‐sized enterprises by giving them loan guarantees and interest bonuses (AS/Pol/Inf, 2020). These measures applied to natural persons, sole traders and enterprises with up to 250 employees (Slov‐Lex, 2020).

When it comes to housing policies, the government prohibited the unilateral termination of lease agreements until June 30, 2020, and those renting property have until December 31, 2020, to pay their debts (Eversheds Sutherland, 2020).

The government also made it easier to pay taxes, as it postponed the statutory income tax. It also postponed the deadlines for making financial statements and annual reports. Another tax break involved giving relief from import duties and VAT on medical supplies from third countries. During the emergency period, the government also discontinued tax controls and proceedings, except for the cases that resulted in refunds (AS/Pol/Inf, 2020; Národná rada Slovenskej republiky, 2020). The government also announced a deferral of payroll and corporate tax payments for businesses whose revenues decline by more than 40% (IMF, 2020).

Since all the measures against COVID‐19 have been temporary, it is difficult to see how they will lead to any long‐term changes in the Slovak welfare state, other than that these policy changes show that the state has been able to take action for able to intervene in the market to take measures to support society, which runs against neo‐liberal dogmas about letting the markets solve social problems. Similar to Hungary and Poland, the new centre‐right government has taken an aggressive attitude against feminist causes and the promotion of gender equality. Because of the government's anti‐feminist stance, the head of gender equality department at the ministry of labour social affairs, Oľga Pietruchová, resigned her position, claiming that the government is ignoring expert opinion in such areas as policies to promote gender equality. She also criticized its attempt to restrict abortions (ParlamentniListy.cz, 2020; Pravda, 2020c). Nevertheless, the country still has not officially withdrawn its signature from Istanbul Convention despite that fact that it informed the EU of its intentions even before the pandemic began (Gehrerová, 2020).

Even though the government's strong performance on the pandemic might be expected to win it support among those who do not mind its conservative gender stance, the ruling coalition has been plagued by plagiarism scandals affecting various high‐ranking politicians (e.g., idnes, 2020; Pravda, 2020b).

Notwithstanding political scandals, the strong policy measures which two successive governments took against COVID‐19 show that the government can act responsibly and institute reforms that promote the welfare of the population.

4. COMPARISON OF SOCIAL PROTECTION MEASURES IN RESPONSE TO THE FIRST WAVE OF THE COVID‐19 PANDEMIC

The COVID‐19 pandemic posed major challenges to the social protection systems of the CEE countries. Partly driven by the similarities of their welfare state regimes, many of their responses were akin. However, there are important differences in the ways in which the countries reacted to the first wave of the pandemic. Below, we summarize the major social protection measures that the four countries implemented during quarantine and post‐quarantine time. All four countries focused their policies on employment and business protection by providing downtime allowances to employees/self‐employed, subsidies to employers, creating flexible working conditions and postponing tax payments or even exemption from it.

All four countries have taken similar steps in the field of family policy by offering paid sick leave for parents taking care of small children during the period of closure (Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia) or extending maternity and parental leave benefits until the end of the emergency period (Hungary). In the area of housing policy, the governments in all four countries suspended mortgage payments (for those unable to pay it) during the emergency period.

Differences are clear when it comes to unemployment protection and social assistance. Hungary was the only country which has not extended its support to the unemployed during the quarantine and post‐quarantine period. Lithuania introduced a temporary job search allowance (200 EUR) for people not eligible for unemployment insurance benefit for 6 months; Poland offered a special solidarity cash benefit paid to unemployed for 3 months (EUR 350) that functioned in parallel to the regular unemployment insurance benefits; Slovakia extended the length of unemployment benefit period four times following the end of the normal period of benefits by 6 months. Thus, Poland increased the generosity of unemployment benefits, Lithuania increased coverage and Slovakia increased the duration.

Lithuania stands out by offering more generous social assistance benefits than the other three countries and easing the criteria to receive them. The government in Lithuania has also implemented an innovative social policy measure by offering one‐time lump‐sum payment worth 120–200 EUR to all families with children (depending on the number of children and income of the family), and 200 EUR to pensioners, people who receive disability allowances, that is, to the most vulnerable social groups. The political situation in Lithuania can account for these solidaristic measures because the country was facing parliamentary elections in autumn 2020. The president, who had been recently elected on May 26, 2019, has promised to make Lithuania a ‘welfare state’ and the slogans of reducing poverty and inequality were central also to his presidential election. Meanwhile, the ruling party during the period 2016–2020, the ‘Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union’ also promoted social solidarity and left‐wing ideas. Thus, the coincidence of the outbreak of the COVID‐19 pandemic, and the electoral competition over the 2020 elections that thematized social solidarity led to the approval of special social policy measures in this country. In contrast, the Hungarian government insisted on continuing its previous program of ‘work‐ based society’ as an explicit anti‐thesis of the welfare state (see Szikra, 2019). According to this paradigm, implemented during the previous economic crisis, no handout is provided to people ‘without work.’ In line with the ‘work‐based society’ idea, policies tried to maintain and create jobs through generous subsidies to employers to pay salaries and through the extension of the public works program. Many of those who lost their jobs, however, could not benefit from these actions. Because of the lack of meaningful social assistance benefits in Hungary, the most vulnerable often had to rely on charity and local aid organized by municipalities.

Poland stands out with most liberal social policy solutions, which may sound surprising from a right‐wing conservative government that earlier had implemented some strikingly generous welfare measures (Lendvai & Szelewa, 2020). This country provided the lowest level of wage compensation to companies among the CEE countries at 40% of the minimum wage. A liberal understanding of mortgage protection is reflected in the fact that this decision is left to the discretion of banks. Poland focused more on the self‐employed than the other four countries in its subsidizes to keep businesses solvent. When it comes to protecting the most vulnerable social groups, Poland incrementally extended some of its social insurance schemes, including the unemployment and sickness leave benefits, but issued no new programs for that purpose.

In the area of supporting wages, Slovakia's wage compensation scheme was very generous, providing 80% of previous wages, similar to Hungary. Slovakia also catered to the self‐employed and those employees who were not covered by the social insurance scheme. Similar to Poland and Lithuania, the social insurance system was somewhat extended to compensate workers temporarily out of work for COVID‐19‐related reasons, including sickness, quarantine and the home‐schooling of children. The Slovak government stands out among the four countries in the immediate action that high‐ranked politicians took in wearing masks publicly and initiating firm public health measures (Table S1).

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Governments in all four countries reacted to the COVID‐19 crisis by providing extensive protection for jobs and enterprises, and in most countries, these were coupled with various solidaristic policy responses to care for the most vulnerable population. In Hungary, most policy measures targeted employers in forms of generous labour cost subsidies and tax exemptions. In contrast to the other countries, unemployment benefits and social assistance remained meagre, as they were prior to the crisis, and no extra compensation for home‐based care was provided. In Lithuania, the improvements made in social policy (social assistance and social housing) have long‐term implications. Those with a low income can now enjoy greater government protection against falling into poverty. This comes as a surprise and a contradiction to measures implemented during the 2008–2010 crisis when the government carried out cutbacks (temporal and long term) in family policy, unemployment insurance and sickness benefits (see Aidukaite, 2019). In Slovakia, the policies concerning COVID‐19 are not likely to lead to long‐term changes. An important indirect impact may be that successive governments showed that the state is capable of taking strong measures to improve the general welfare of the population. This situation could lead to a general increase in support for welfare state policies and a decrease in support for neo‐liberal notions claiming that the market can solve the most important social problems. In Poland, we saw more incremental measures that extended some of the already existing social insurance schemes, including unemployment and sickness benefits. Apart from that, it did not implement any particular social policy innovations.

An interesting commonality in the Visegrád countries (Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) is that their right‐wing, conservative governments issued anti‐gender equality changes during the pandemic or at least took steps in proposing such changes. Perhaps, the most remarkable case has so far been Polish Constitutional Tribunal's decision to ban abortion in case of malformation of the foetus. While it is clear that the restrictions on public gatherings made it difficult for the population to organize protests, whether and in what ways these policy changes were connected to the COVID‐19 crisis need further analysis.

In concluding our study, we turn to Vis, van Kersbergen, and Hylands' (2011) claim that during the crisis (2008–2010), regardless of type of welfare state, all countries basically went through three phases: A first phase of emergency capital injections in the banking sector, a second phases of Keynesian demand management and labour market protection and extended social protection and a third stage of austerity measures.

It is too soon to know whether any of the countries in our study will eventually introduce austerity measures, but so far, the countries have all followed the second step of labour market protection by subsidizing employment, and all except Hungary took steps to keep demand up by introducing benefits to those who must stay at home because of the pandemic. Even though the post‐communist countries all have hybrid welfare states that deviate somewhat from the Western models, they all have strong conservative‐Bismarckian elements (see Aidukaite, 2011; Deacon, 1992; Kuitto, 2016), so in this sense, they have also behaved so far similar to Chung and Thewissen's expectations of conservative welfare states. Lithuania, however, deviated from the other three countries not only keeping up with Keynesian demand management and labour market protection but also implementing universal policies and granting more generous benefits for those most in need. In Lithuania, where social policy reforms in this direction are likely to be maintained after the crisis, these changes have a potential to lead to more comprehensive and universal social policies in the future.

Overall, we conclude that Hungary, previously a high‐spender on social protection (see Figure 1), has done the least to enhance social solidarity, while Lithuania, the country worst‐affected by the Great Recession and lowest on social spending in the past decade, has used this crisis in the most innovative and supportive way protect its population. Slovakia and Poland, mid‐range spenders on social protection earlier, fell in between the two extremes with somewhat extended social protection in Poland and prompt and definite public health‐related measures in Slovakia. It is a question of further research whether Eastern European countries will stay on the welfare tracks detected here to cushion the effects of the second wave of the pandemic and a possibly more endurable economic and social crisis.

Supporting information

Table S1. Social protection measures implemented to ease the Covid‐19 crisis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Czech Grant Agency under Grant 19–12289S; Slovak Grant Agency: APVV‐17‐0596; the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union, project number 611572‐EPP‐1‐201 9‐1‐SK‐EPPJ MO‐CHAIR; the Swedish Research Council FORMAS (Grant No. 2016–00258).

Aidukaite J, Saxonberg S, Szelewa D, Szikra D. Social policy in the face of a global pandemic: Policy responses to the COVID‐19 crisis in Central and Eastern Europe. Soc Policy Adm. 2021;55:358–373. 10.1111/spol.12704

Funding information Slovak Grant Agency, Grant/Award Number: APVV‐17‐0596; The Czech Grant Agency, Grant/Award Number: 19‐12289S; The Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union, Grant/Award Number: 611572‐EPP‐1‐201 9‐1‐SK‐EPPJ MO‐CHAIR; The Swedish Research Council FORMAS, Grant/Award Number: 2016‐00258

REFERENCES

- Aidukaite . (2019). The welfare systems of the Baltic States following the recent financial crisis of 2008/2010: Expansion or retrenchment? Journal of Baltic Studies, 50(1), 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Aidukaite, J. (2011). Welfare reforms and socio‐economic trends in the ten new EU member states of central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Communist and Post‐Communist Studies, 44(3), 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Aidukaite, J. (2014). Housing policy regime in Lithuania: Towards liberalization and marketization. GeoJournal, 79(4), 421–432. [Google Scholar]

- Aidukaite, J. , Moskvina, J. , & Skuciene, D. (2016). Lithuanian welfare system in times of recent crisis. In Schubert K., de Villota P., & Kuhlmann J. (Eds.), Challenges to European welfare systems (pp. 419–441). Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- AS/Pol/Inf . (2020). The legislative and oversight role of parliaments in the context of the Covid‐19 pandemic: Replies received by national parliaments of the Council of Europe members States to a questionnaire submitted via the European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation (ECPRD), Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy.

- Bohle, D. , & Greskovits, B. (2007). Neoliberalism, embedded neoliberalism, and neocorporatism: Paths towards transnational capitalism in Central‐ Eastern Europe. West European Politics, 30(3), 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- Cerami, A. (2006). Social policy in central and Eastern Europe. The emergence of a new European welfare regime. LIT Verlag: Münster, Hamburg, Berlin, Vienna, London.

- Cerami, A. , & Vanhuysse, P. (Eds.). (2009). Post‐communist welfare pathways. Theorizing social policy transformations in central and Eastern Europe. Basignstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H. , & Thewissen, S. (2011). Falling back on old habits? A comparison of the social and unemployment crisis reactive policy strategies in Germany, the UKand Sweden. Social Policy and Administration, 45(4), 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, B. (1992). East European welfare: Past, present and future in comparative context. In Deacon B. (Ed.), The new Eastern Europe: Social policy past, present and future (pp. 1–31). London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Els . (2020). Pagalba verslui karantino laikotarpiu [Support to business during the quarantine period]. Retrieved from https://els.lt/pagalba-verslui-karantino-laikotarpiu/

- Escobar, L. E. , Molina‐Cruz, A. , & Barillas‐Mury, C. (2020). BCG vaccine protection from severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). PNAS, 117(30), 17720–17726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound . (2020). Anti‐crisis shield: Employment protection and wage subsidies, case PL‐2020‐14/526 (measures in Poland). COVID‐19 EU PolicyWatch, Dublin. Retrieved July 20, 2020 from http://eurofound.link/covid19eupolicywatch.

- European Commission Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs . (2020). Policy measures taken against the spread and impact of the coronavirus – April 14, 2020. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/policy_measures_taken_against_the_spread_and_impact_of_the_coronavirus_14042020.pdf

- Eversheds Sutherland . (2020). Coronavirus ‐ Lex COVID‐19 amendments – Slovakia. Retrieved from https://www.eversheds-Sutherland.com/global/en/what/articles/index.page?ArticleID=en/coronavirus/Coronavirus-Lex-COVID-19-amendments-Slovakia.

- Financial report . (2020). Slovenskú ekonomiku čaká ešte väčší prepad. Oživenie by malo prísť až v treťom kvartáli tohto roku. Retrieved from https://www.finreport.sk/ekonomika/slovensku-ekonomiku-caka-este-vacsi-prepad-ozivenie-by-malo-prist-az-v-tretom-kvartali-tohto-roku/.

- Gabrizova, Z. (2020). Slovakia's health minister: No second wave yet. EURACTIV Slovakia, 13 March, Updated 9 July. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/health-consumers/short_news/slovakia-covid-19-update/.

- Gazeta Prawna (2019). Zasiłek Dla Bezrobotnych w 2020 Roku: Kto Może Otrzymać? Ile Dostaje Siȩ “Na Rȩkȩ”? ‐ Praca i Kariera ‐ GazetaPrawna.Pl ‐ Prawo i Rynek Pracy’. Retrieved 21 January 2021. Retrieved from https://praca.gazetaprawna.pl/artykuly/1433962,zasilek-dla-bezrobotnych-w-2020-roku-kto-moze-otrzymac-ile-dostaje-sie-na-reke.html.

- Gehrerová, R. (2020). Čo je s Istanbulským dohovorom? Predvolebná antikampaň Ani Parlament nič Nezmenili. Denníka N, 28 May. Retrieved from https://dennikn.sk/1909173/co-je-s-istanbulskym-dohovorom-predvolebna-antikampan-ani-parlament-nic-nezmenili/?fbclid=IwAR3utMt4bDB-YB0CG-a-6-WrLCcdMa5TwlKZOlqxtZwNPxdak40Jby88LF0.

- Government of Poland . (2020). Tarcza Antykryzysowa [Anti‐Crisis Shield]. Retrieved December 30, 2020 from https://www.gov.pl/web/tarczaantykryzysowa.

- GRAPE . (2020). Diagnoza Rynku Pracy. Wyniki badań z 22‐28 czerwca 2020 [labour market diagnosis. Results of the survey from 22 to 28 Jue 2020]. Retrieved July 28, 2020 from https://diagnoza.plus/bezrobocie-w-czerwcu-2020/.

- Gyulavári, T. (2020). Covid‐19 and Hungarian labour law: ‘The state of danger’. Hungarian Labour Law, E‐Journal, 13(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, R. , & Kaufman, R. (2008). Development, democracy, and welfare states: Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- idnes . (2020). Plagiátor Kollár zůstává šéfem parlamentu, Matovičova vláda ustála Krizi. 7 July. Retrieved from https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/zahranicni/slovensko-plagiator-boris-kollar-hlasovani-o-odvolani-parlament-vlada-matovic.A200707_184630_zahranicni_kha.

- IMF . (2020). Policy Responses to Covid‐19. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#C.

- Jahn, D. (2017). Distribution regimes and redistribution effects during retrenchment and crisis: A cui bono analysis of unemployment replacement rates of various income categories in 31 welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 28(5), 433–451. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, D. , & Kuitto, K. (2011). Taking stock of policy performance in central and Eastern Europe: Policy outcomes between policy reform, transitional pressure and international influence. European Journal of Political Research, 50, 719–748. [Google Scholar]

- Javornik, J. (2014). Measuring state de‐familialism: Contesting post‐socialist exceptionalism. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(3), 240–257. [Google Scholar]

- Javornik, J. , & Kurowska, A. (2017). Work and care opportunities under different parental leave systems: Gender and class inequalities in Northern Europe. Social Policy & Administration, 51(4), 617–637. [Google Scholar]

- Kolenčík, M. (2020). How Slovakia fought COVID‐19. NCT Magazine. Retrieved from https://nct-magazine.com/nct-magazine-june-2020/how-slovakia-fought-covid-19/

- Köllő, J. (2019). Toward a ‘work based society’? In Trencsényi B. & Kovács J. M. (Eds.), Brave new Hungary: Mapping the ‘system of national cooperation’ (pp. 139–158). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Kuitto, K. (2016). Post‐communist welfare states in European context. Patterns of welfare policies in Central and Eastern Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lendvai, N. (2008). Incongruities, paradoxes, and varieties: Europeanization of welfare in the new member states. Paper presented at the ESPAnet conference, 18–20 September 2008, Helsinki.

- Lendvai, N. , & Szelewa, D. (2020). Governing new authoritarianism: Populism, nationalism and radical welfare reforms in Hungary and Poland. Social Policy and Administration. 10.1111/spol.12642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lietuvos Socialinės apsaugos ir darbo ministerija (LMSSL) . (2020). Seimas patvirtino pagalbą po karantino: Naudą pajus 1,4 mln. Lietuvos gyventojų [The Seimas approved aid after quarantine: 1.4 million of Lithuanians will benefit]. Retrieved from http://socmin.lrv.lt/lt/naujienos/seimas-patvirtino-pagalba-po-karantino-nauda-pajus-1-4-mln-lietuvos-gyventoju

- Lrytas . (2020). Vienkartinės išmokos vaikams šeimas pasieks jau šią savaitę [Lump sum payments for children will reach families as early as this week]. Retreieved from https://www.lrytas.lt/verslas/mano-pinigai/2020/07/22/news/vienkartines-ismokos-vaikams-seimas-pasieks-jau-sia-savaite-15698652/

- Molnár, G. , Bazsalya, B. , Bódis, L. , & Kálmán, J. (2019). Public works in Hungary: Actors, allocation mechanisms and labour mobility effects. Social Science Review, 7, 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Naczyk, M. (2020). Presentation during a webinar Progressive Response to the Pandemic Crisis that took place on the 2nd of June 2020 within the frames of Warsaw Debates on Social Policy. Warsaw: ICRA Foundation and Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Warsaw Office.

- Národná rada Slovenskej republiky . (2020). Posledné schválené zákony. Retrieved from https://www.nrsr.sk/web/default.aspx?SectionId=184.

- Nemzeti Foglalkoztatási Szolgálat – NFSZ . (2020). Idősoros adatok. (Longitudinal data). Retrieved from https://nfsz.munka.hu/tart/stat_teruleti_bontas.

- OECD . (2019). Society at a glance 2019: OECD social indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from 10.1787/soc_glance-2019-en. [DOI]

- OECD . (2020). OECD data. Retrieved from https://data.oecd.org/

- Orosz, É. (2018). Catching up with or Lagging behind the EU15 Countries? Revealing the Patterns of Changes in Health Status, Health Spending and Health System Performance in Four Post‐ socialist EU Countries. ATINER'S conference paper series, no: HEA2018‐2557. Athens.

- Our World in Data . (2020). Corona virus data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/

- ParlamentniListy.cz . (2020). Nadávala “bílému odpadu,” Na Ministerstvu řídila Odbor Rovnosti pohlaví. Teď končí a na závěr ještě pořádně Zasmradila. 22 May. Retrieved from https://www.parlamentnilisty.cz/arena/monitor/Nadavala-bilemu-odpadu-na-ministerstvu-ridila-odbor-rovnosti-pohlavi-Ted-konci-a-na-zaver-jeste-poradne-zasmradila-624772.

- Pravda . (2020a). Pietruchová končí ako šéfka odboru rodovej rovnosti. 20 May. Retrieved from https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/552035-pietruchova-konci-sefka-odboru-rodovej-rovnosti/?fbclid=IwAR0Knfo_TfMTvTF3Rw0PzjOkrPLBWrEJ1YfRlEN082C1yCKWVeJd5l3lXVE.

- Pravda . (2020b). Kollár a Krištúfková majú spoločný problém: Ich práce majú byť plagiáty. 23 June. Retrieved from https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/555356-beblavy-kristufkova-je-horsia-plagiatorka-ako-danko/

- Pravda . (2020c). Poslanci hlasovali o novele potratového zákona, je v druhom čítaní. 14 July. Retrieved from https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/557241-poslanci-budu-hlasovat-o-novele-potratoveho-zakona/.

- Prime Minister of Poland . (2020). Prime Minister: We have introduced the state of epidemic in Poland. Retrieved July 26, 2020 from https://www.premier.gov.pl/en/news/news/prime-minister-we-have-introduced-the-state-of-epidemic-in-poland.html.

- Rat, C. , & Szikra, D. (2018). Family policies and social inequalities in central and Eastern Europe. A comparative analysis of Hungary, Poland and Romania between 2005 and 2015. In Eydal G. B. & Rostgaard T. (Eds.), Handbook of child and family policy. Cheltenham, Northhamton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Saxonberg, S. (2014). Gendering family policies in post‐communist Europe: A historical‐institutional analysis. England: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Saxonberg, S. , & Sirovátka, T. (2014). From a garbage can to a compost model of decision‐making? Social policy reform and the czech government’s reaction to the international financial crisis. Social Policy & Administration, 28(4), 450–467. [Google Scholar]

- Saxonberg, S. , & Sirovátka, T. (2019). Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge Handbook of the Welfare State, Routledge International Handbooks, (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Slovensko.sk . (2020). Nemocenské. Retrieved from https://www.slovensko.sk/sk/agendy/agenda/_nemocenske-1/.

- Slov‐Lex . (2020). 67/2020 Z. z. Retrieved from https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2020/67/.

- Social‐demokratai . (2020). Karantinas. Darbuotojų teisės, kompensacijos, pagalba [Quarantine. Workers' rights, compensation, assistance]. Retrieved from https://www.lsdp.lt/karantinas/

- Szelewa, D. (2014). The second wave of anti feminism? Post crisis maternalist policies and the attack on the concept of gender in Poland. Gender, Rovné Příležitosti, Výzkum, 15(2), 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Szelewa, D. (2017). From implicit to explicit Familialism: Post‐1989 family policy reforms in Poland. In Auth D., Hergenhan J., & Holland‐Cunz B. (Eds.), Gender and family in European economic policy. Developments in the new Millenium (pp. 129–156). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan published by Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Szikra, D. (2014). Democracy and welfare in hard times: The social policy of the Orbán government in Hungary between 2010 and 2014. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(5), 486–500. [Google Scholar]

- Szikra, D. (2019). Ideology or pragmatism? Interpreting social policy change under the ‘system of national cooperation’. In Kovács J. M. & Trencsényi B. (Eds.), Brave new Hungary: Mapping the ‘system of national cooperation’ (pp. 225–241). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Szikra, D. , & Tomka, B. (2009). Social policy in east Central Europe: Major trends in the 20th century. In Cerami A. & Vanhuysse P. (Eds.), Welfare state transformations and adaptations in central and Eastern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Tomak, R. (2020). European nation with fewest virus deaths proves speed is key. Blomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-28/european-nation-with-least-virus-deaths-proves-speed-is-key.

- Vis, B. , van Kersbergen, K. , & Hylands, T. (2011). To what extent did the financial crisis intensify the pressure to reform the welfare state? Social Policy and Administration, 45(4), 338–353. [Google Scholar]

- Worldometer . (2020). Corona virus cases in Lithuania. Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/lithuania/

- ZUS . (2020a). Dodatek solidarnościowy [Solidarity supplement]. Retrieved July 28, 2020 from https://www.zus.pl/o-zus/aktualnosci/-/publisher/aktualnosc/1/dodatek-solidarnosciowy/2593418.

- ZUS . (2020b). Polski Bon Turystyczny [Polish Tourist Voucher]. Retrieved July 28 2020 from https://www.zus.pl/o‐zus/aktualnosci/‐/publisher/aktualnosc/1/polski‐bon‐turystyczny/3496246.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Social protection measures implemented to ease the Covid‐19 crisis.