Abstract

We report catalytic strategies to synthesize and release chemicals for applications in fine chemicals, such as drugs and polymers from a biomass-derived chemical, 5-hydroxymethyl furfural (HMF). The combination of the diene and aldehyde functionalities in HMF enables catalytic production of acetalized HMF derivatives with diol or epoxy reactants to allow reversible synthesis of norcantharimide derivatives upon Diels-Alder reaction with maleimides. Reverse-conversion of the acetal group to an aldehyde yields mismatches of the molecular orbitals in norcantharimides to trigger retro Diels-Alder reaction at ambient temperatures and releases reactants from the coupled molecules under acidic conditions. These strategies provide for the facile synthesis and controlled release of high-value chemicals.

Keywords: Hydroxymethylfurfural, Diels-Alder, Maleimides, Drug delivery, Acetals

Graphical Abstract

Biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethyl furfural (HMF) is utilized as a catalytic platform for facile synthesis and release of high-value chemicals that can serve as therapeutic ingredients and/or polymeric materials. Acetalization and hydrolysis of the aldehyde group in HMF can be used to control the reactivity of the diene functionality for the Diels-Alder reaction. The combination of aldehyde and diene in HMF, thus, acts as a ‘chemical-switch’.

Biomass conversion is a sustainable source of energy and chemicals, which can mitigate environmental concerns and produce high-value materials from non-edible plants1,2. Current trends in decreasing prices of transportation fuels and increasing importance of individual health treatment and environmental protection have created new opportunities for biomass conversion in pharmaceutical3,4 and renewable polymer applications5,6. Synthesis and release of chemicals, which are of critical importance for fine chemicals, involve the following key chemical challenges: (i) designing a material that provides chemical bonding sites, (ii) incorporating a mechanism that releases the chemical at ambient temperatures, and (iii) controlling the release mechanism at the desired target. We show that all of these challenges can be fulfilled by the synthesis of materials containing a furan group conjugated to an aldehyde group, such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) that is effectively produced from biomass7. A key chemical property of HMF that has not been utilized previously8 is this conjugation between the diene and aldehyde functionalities. In particular, the electron-withdrawing nature of aldehyde group inhibits the reactivity of diene group in HMF to undergo Diels-Alder reactions with dienophiles. However, by converting the aldehyde group in HMF to an electron-donating hydroxyl group, HMF can append maleimide-based chemicals through Diels-Alder coupling9. Maleimides, containing a dienophilic C=C bond and imide functionalities, have served as sites to append additional chemicals for the synthesis of therapeutic molecules, such as norcantharimides10,11 and antibody-drug-conjugates12,13, and for the production of novel polymers14. Moreover, acetalization of HMF not only produces an electron-rich diene for Diels-Alder reaction, but it also alters the reversibility of acetal formation and thereby allows for the controlled release of chemicals by hydrolysis15,16. Accordingly, the combination of acetalized HMF and maleimide provides a catalysis platform to control the synthesis and release of chemicals.

Herein, we synthesize various norcantharimide derivatives from biomass-derived HMF by acetalization over an acid catalyst, Amberlyst-15, followed by Diels-Alder reaction with maleimide. The norcantharimides release the starting materials by retro Diels-Alder reaction that is triggered by acetal hydrolysis under acidic (≤pH 3) conditions. The synergy of the furan and aldehyde functionalities in HMF thus enables the production of therapeutic and polymeric materials, and the controlled chemical release at ambient temperatures (35–60⁰C). Scheme 1 describes reaction schemes for the synthesis and release of norcantharimide derivatives.

Scheme 1.

Reaction pathways for acid-catalyzed HMF acetalization with (A) primary alcohols, (B) polyols, (C) epoxybutane, and (D) epoxybutane dimerization; (E) Diels-Alder reaction of maleimide and acetalized HMF; (F) Chemical release by acetal hydrolysis and triggered retro Diels-Alder reaction.

HMF acetalization with various alcohols (Scheme 1.A, B) was examined over Amberlyst-15 catalyst in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at 35⁰C (Figure S9-S18, Table S1). None of the primary alcohols (Entry 1–4 in Table S1) reacted with HMF, whereas the acid catalyst facilitated HMF self-condensation (Entry 5 in Table S1, Figure S28). HMF self-condensation into humins occurred when the molar ratio of HMF to 1,3-propanediol (1,3-PD) was 1:1. In contrast, larger amounts of 1,3-PD (>2 equivalent diol to HMF) suppressed HMF self-condensation by increasing the reaction between 1,3-PD and HMF. Acetalization of HMF and 1,3-PD reached an equilibrium yield of 92%17 within 3% error, after 4 h of reaction (Figure 1.A). The consumption of two reactants was equivalent at each reaction time, indicating the absence of side-reactions (Figure S1). The absence of side-reactions allows for characterization of feeds and products by assigning the chemical shifts in NMR spectra and thereby quantifying the conversion and yield. 1,3-propanediol derivatives with HMF (Entry 7,9,13 in Table S1) synthesized 6-member cyclic acetals in high yield (>93%). The electronegative sp2 carbon in 2-methylene-1,3-propanediol (Entry 14 in Table S1) produced a less stable 6-member cyclic acetal in lower yield (66.7%). Low pentaerythritol (Entry 15 in Table S1) solubility in THF induced colloidal phase reaction and resulted in 66.7% yield. 55% product yields were achieved from ethylene glycol (EG) derivatives by producing 5-member cyclic acetals (Entry 6,8 in Table S1). Production of larger cyclic acetals (≥7-member ring), which have higher ring strain than 6-member ring, resulted in the lowest yield from 20.4% to 33.7% (Entry 10–12 in Table S1). These results demonstrate that the structural stability of cyclic acetals affects the product yield in acetalization. Furthermore, epoxybutane reacted with HMF to synthesize a 5-member cyclic acetal (Epoxy-HMF) in Scheme 1.C. Excess amounts of epoxybutane (8 equivalent epoxybutane to HMF) improved product yield up to 15.4% (Entry 5,9 in Table S2) with equivalent molar ratio of R- and S-diastereoisomer (Figure S19). However, a large excess of epoxybutane without THF solvent facilitated epoxybutane dimerization (Figure S29) as a side-reaction (Scheme 1.D) resulting in low (<6%) product yield (Entry 3,6 in Table S2). The entropy penalty of the bimolecular reaction explains the lower yield (15.4%) of 5-member cyclic acetal, compared to the product yield (55.6%) from ethylene glycol reactant.

Figure 1.

(A) HMF conversion, 1,3-PD conversion, and acetalized HMF (1,3-PD-HMF) yield at different reaction time, Error bar: ±3% deviation, HMF conversion and 1,3-PD-HMF yield are overlapped (Reaction conditions: 35⁰C); (B) Yield of endo- and exo-1,3-PD-HMF-MAL (Reaction conditions: 50⁰C, 67 h).

The acetalization of the aldehyde group in HMF provides an electron-rich diene and enables Diels-Alder reaction with maleimide (Scheme 1.E). The products were analyzed by NMR spectra (Figure S20-S27) because there was no side-reaction, such as degradations of HMF and maleimide, under the reaction conditions of Diels-Alder reaction (Figure S30). Figure 1.B shows that 2 equivalent maleimide to acetalized HMF resulted in high yield (94.7%) of the norcantharimide derivative (Entry 2 in Table 1). The highest yield (90.9–95.2%) was obtained from 6-member cyclic acetals (Entry 2,3,7,9 in Table 1). The electronegative sp2 carbon induced a less stable cyclic acetal and contributed to lower (75.5%) product yield (Entry 8 in Table 1). Moreover, low yields (≤64.1%) of Diels-Alder products were produced from acetalized HMF derivatives that possessed larger ring strain than 6-member cyclic acetals (Entry 1,4,5,6 in Table 1). As a result, chemical properties of the cyclic acetals, such as ring stability and electronegativity, affect the formation of norcantharimide derivatives, but the molar ratio of endo- and exo-diastereoisomers remained constant (endo-: exo- = 4:1, Figure S21-S26). Endo-selective coupling by Diels-Alder reaction of furans and maleimides is consistent with previous literature18. The endo-isomer is kinetically preferred to the exo-isomer by aligning the diene and dienophile molecular orbitals. Sequential reactions of acetalization and Diels-Alder coupling can be used to synthesize a polymer14. HMF-Pentaerythritol-HMF (HPH) and bis-maleimide were soluble in THF, whereas the Diels-Alder polymer of two monomers precipitated in THF by forming a solid material during polymerization (Figure S6.D). The polymerized material had low solubility in various organic solvents (THF, methanol, acetone, chloroform). Oligomers smaller than pentamers (Mn≤1513 g∙mol−1 and Mw≤1599 g∙mol−1) were dissolved in THF and characterized by GPC analysis (Figure S6.A) with polystyrene as a calibration standard (Figure S6.B).

Table 1.

Product yields and reaction conditions of Diels-Alder reaction of acetalized HMF and maleimide (Solvent: THF, Product yields were measured by NMR in Figure S20-S27, Trace yields represent uncertain yield from NMR resolution limit).

| Entry | Acetalized HMF feed |

Malemide/Acetalized HMF (mol) |

Temp. (°C) |

Time (day) |

Product Yield (%) |

Product structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

2.3 | 50 | 3 | 64.1 |  |

| 2 |  |

2.0 | 50 | 3 | 94.7 |  |

| 3 |  |

2.2 | 50 | 3 | 93.5 |  |

| 4 |  |

2.2 | 50 | 3 | 50.0 |  |

| 5 |  |

2.3 | 50 | 3 | Trace (~21.7) |  |

| 6 |  |

2.3 | 50 | 3 | Trace (~33.3) |  |

| 7 |  |

2.2 | 50 | 3 | 95.2 |  |

| 8 |  |

2.3 | 50 | 3 | 75.5 |  |

| 9 | 2.3 | 50 | 3 | 90.9 |  |

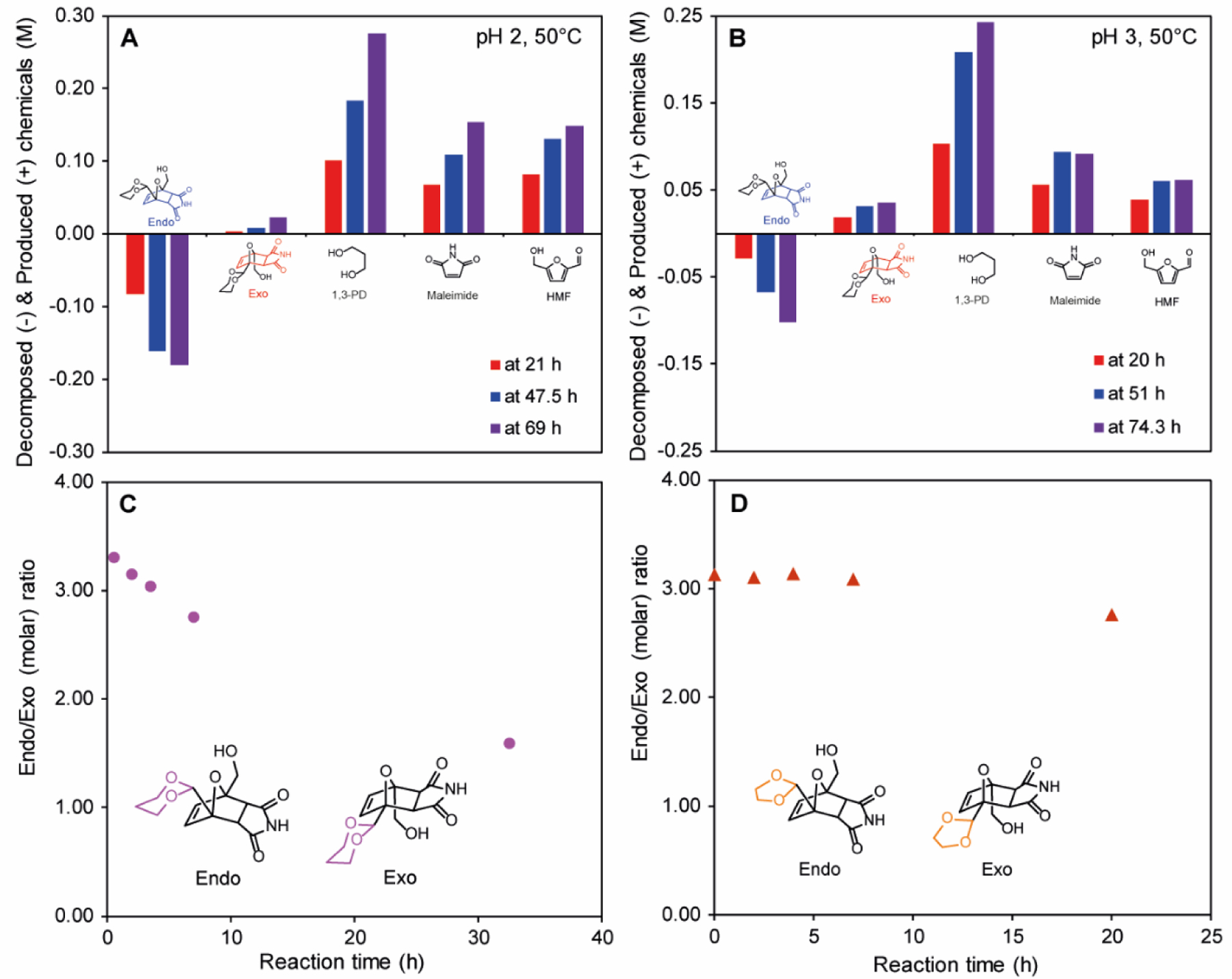

Hydrolysis of the acetal group triggers molecular orbital mismatch in Diels-Alder coupled chemicals. Therefore, retro Diels-Alder reaction that is typically achieved by increasing the temperature can be triggered by acid-catalyzed acetal hydrolysis at constant temperature (Scheme 1.F and Figure S8.C). The effect of pH on the release rate was investigated using a 6-member cyclic acetal (1,3-PD-HMF-MAL) at 50⁰C (Figure 2.A, B). Exo-isomer was synthesized in the reaction system because exo-1,3-PD-HMF-MAL was thermodynamically the most stable chemical in the system (Figure S5.B). The rate constants were measured by tracking the concentration of endo-isomer in different pH (Figure S4). By decreasing pH from 3 to 2, the rate constant increased from 4.36∙10−5 to 9.84∙10−5 M−1s−1 at 50°C. At higher pH conditions, the rate of acetal hydrolysis decreased and side-reactions, such as maleimide degradation became more important. In pH 4 and 5 buffers, competition between acetal hydrolysis, chemical degradation, and Diels-Alder reaction resulted in fluctuations of chemical concentrations (Figure S2). The triggered retro Diel-Alder reaction and degradations of maleimide and HMF in the chemical release system are independent reaction pathways that resulted from acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. Accordingly, tracking the concentration of each chemical in the feed and product solutions allows for investigation of these parallel reactions.

Figure 2.

Concentrations of consumed (−) and produced (+) chemicals versus time by chemical release of 1,3-PD-HMF-MAL solution in (A) pH 2, (B) pH 3 acetate buffer at 50°C (Initial chemical concentrations of (A) were endo-, exo-, 1,3-PD, malemide, HMF were 0.62, 0.19, 0.66, 0.54, 0.00 M, respectively; Initial chemical concentrations of (B) were endo-, exo-, 1,3-PD, malemide, HMF were 0.56, 0.18, 0.74, 0.64, 0.07 M, respectively); Molar ratio of diastereoisomers versus time in (C) 1,3-PD-HMF-MAL, and (D) EG-HMF-MAL solution in pH 2 acetate buffer at 60⁰C. (Concentration of endo- and exo-isomers were measured by HPLC).

Furthermore, the 5- and 6-member cyclic acetals (Scheme 1.F) were used to compare the structural and/or thermodynamic stability effect on the reaction kinetics of chemical release at 35, 50, and 60⁰C in pH 2 buffer. Activation energies of endo-1,3-PD-HMF-MAL, endo-EG-HMF-MAL, and exo-EG-HMF-MAL were measured to be 108, 92, and 86 kJ∙mol−1, respectively (Figure S5.A). The activation energies of triggered retro Diels-Alder reaction are lower than that of thermal retro Diels-Alder reaction (157 kJ∙mol−1) of a previously reported furan-maleimide adduct18. By comparison of exo- and endo-isomers, a lower activation energy (86 kJ∙mol−1) of exo-EG-HMF-MAL than endo-counterpart (92 kJ∙mol−1) results from thermodynamic stability of exo-conformation (Figure S5.C). A similar comparison of 5- and 6-member cyclic acetals shows that a lower structural stability of EG-HMF-MAL (5-member ring) contributes to lower activation energy than 1,3-PD-HMF-MAL (6-member ring) and accelerates chemical release rate (Figure S5.B, C). 21.9% of 1,3-PD-HMF-MAL, including endo-isomer decomposition and exo-isomer formation, was decoupled after 32.5 h, while 42.7% of EG-HMF-MAL was hydrolyzed after 20 h (Figure S3).

The molar ratio of diastereoisomers decreased by acetal hydrolysis in 1,3-PD-HMF-MAL solution due to the decomposition of endo-isomer and the formation of exo-isomer (Figure 2.C). Meanwhile, similar hydrolysis rate constants of endo- and exo-EG-HMF-MAL (kendo=4.27∙10−4 M−1∙s−1 and kexo=4.07∙10−4 M−1∙s−1 in Figure S5.A) maintained the diastereoisomers ratio constant during the reaction (Figure 2.D). The difference of diastereoisomer ratio in feed, measured by HPLC (endo/exo=3.3) and by NMR (endo/exo=4.0), resulted from the overlap of the isomers peaks in HPLC analysis (Figure S8), and it underestimated concentrations of endo- and exo-compounds in Figure 2.A and B.

Biomass-derived HMF can be utilized as a catalytic platform for facile synthesis and release of high-value chemicals, such as norcantharimide derivatives. Acid-catalyzed acetalization of HMF activates a ‘chemical-switch’ and enables Diels-Alder reaction by converting the electron-withdrawing aldehyde to an electron-donating acetal. As the chemical stabilities of the cyclic acetals increase, the yields of desired products by acetalization and Diels-Alder reaction increase. Then, hydrolysis of the acetal linkage can be employed to turn off the ‘chemical-switch’ in the Diels-Alder coupled molecules and trigger the release of starting materials at ambient temperatures (35–60⁰C). At low pH (≤pH 3) conditions, chemical release from norcantharimides can be achieved at constant temperature, whereas chemical release is suppressed at higher pH (≥pH 4) conditions. The controlled chemical release at 35⁰C implies that this release strategy could be utilized in drug delivery systems at human body temperature. For example, the diol groups in HMF-Pentaerythritol-HMF monomers can be reacted with terephthalic acids to produce solid polyesters6, and the coupling of the furan groups to maleimides (Entry 9 in Table 1) could serve as a maleimide-based drug carrier.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Mass Spectrometry and NMR facilities that are funded by: Thermo Q ExactiveTM Plus by NIH 1S10 OD020022–1; Bruker Quazar APEX2 and Bruker Avance-500 by a generous gift from Paul J. and Margaret M. Bender; Bruker Avance-600 by NIH S10 OK012245; Bruker Avance-400 by NSF CHE-414 1048642 and the University of Wisconsin-Madison;

Funding: This material is based upon work supported in part by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE-SC0018409 and in part by U.S. Department of Energy under Award Number DE-EE0008353;

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Competing interests: Authors declare no competing interests;

Data and materials availability: All data is available in the main text or the supporting information.

References

- 1.Serrano-Ruiz JC, West RM and Dumesic JA, Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng, 2010, 1, 79–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chheda JN, Huber GW and Dumesic JA, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed, 2007, 46, 7164–7183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuo Z and Macmillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 5257–5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng W, Wang Y, Zhang S, Gupta KM, Hülsey MJ, Asakura H, Liu L, Han Y, Karp EM, Beckham GT, Dyson PJ, Jiang J, Tanaka T, Wang Y and Yan N, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2018, 115, 5093–5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang H, Motagamwala AH, Huber GW and Dumesic JA, Green Chem, 2019, 21, 5532–5540. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warlin N, Garcia Gonzalez MN, Mankar S, Valsange NG, Sayed M, Pyo SH, Rehnberg N, Lundmark S, Hatti-Kaul R, Jannasch P and Zhang B, Green Chem, 2019, 21, 6667–6684. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motagamwala AH, Huang K, Maravelias CT and Dumesic JA, Energy Environ. Sci, 2019, 12, 2212–2222. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan W, Verrier C, Queneau Y and Popowycz F, Curr. Org. Synth, 2019, 16, 583–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galkin K, Kucherov F, Markov O, Egorova K, Posvyatenko A and Ananikov V, Molecules, 2017, 22, 2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng SS, Shi Y, Ma XN, Xing DX, Liu LD, Liu Y, Zhao YX, Sui QC and Tan XJ, J. Mol. Struct, 2016, 1115, 228–240. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puerto Galvis CE, Vargas Méndez LY and Kouznetsov VV, Chem. Biol. Drug Des, 2013, 82, 477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christie RJ, Fleming R, Bezabeh B, Woods R, Mao S, Harper J, Joseph A, Wang Q, Xu ZQ, Wu H, Gao C and Dimasi N, J. Control. Release, 2015, 220, 660–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyon RP, Setter JR, Bovee TD, Doronina SO, Hunter JH, Anderson ME, Balasubramanian CL, Duniho SM, Leiske CI, Li F and Senter PD, Nat. Biotechnol, 2014, 32, 1059–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goussé C and Gandini A, Polym. Int, 1999, 48, 723–731. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies ER and Fréchet JMJ, Chem. Commun, 2003, 3, 1640–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlossbauer A, Dohmen C, Schaffert D, Wagner E and Bein T, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed, 2011, 50, 6828–6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M, Su Y, Fukuoka A, Hensen EJM and Nakajima K, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed, 2018, 57, 8235–8239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Froidevaux V, Borne M, Laborbe E, Auvergne R, Gandini A and Boutevin B, RSC Adv, 2015, 5, 37742–37754. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.