Abstract

Background

Dengue infection is caused by an arbovirus with a wide range of presentations, varying from asymptomatic disease to unspecific febrile illness and haemorrhagic syndrome with shock, which can evolve to death. In Brazil, the virus circulates since the 1980s with many introductions of new serotypes, genotypes, and lineages since then. Here we report a fatal case of dengue associated with a Dengue virus (DENV) lineage not detected in the country until now.

Case presentation

The patient, a 58-year-old man arrived at the hospital complaining of fever and severe abdominal pain due to intense gallbladder edema, mimicking acute abdomen. After 48 h of hospital admission, he evolved to refractory shock and death. DENV RNA was detected in all tissues collected (heart, lung, brain, kidney, spleen, pancreas, liver, and testis). Viral sequencing has shown that the virus belongs to serotype 2, American/Asian genotype, in a new clade, which has never been identified in Brazil before. The virus was phylogenetically related to isolates from central America [Puerto Rico (2005–2007), Martinique (2005), and Guadeloupe (2006)], most likely arriving in Brazil from Puerto Rico.

Conclusion

In summary, this was the first fatal documented case with systemic dengue infection associated with the new introduction of Dengue type 2 virus in Brazil during the 2019 outbreak.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-021-05959-2.

Keywords: Dengue virus, Dengue virus type 2, Autopsy, Fatal case, Case report

Background

Dengue virus (DENV) is the world’s most important arbovirus in terms of morbidity, mortality, and economic impact for humans [1]. DENV are arthropod-borne viruses associated with Aedes vectors [2], belong to the genus Flavivirus (family Flaviviridae) [3, 4], and are classified in four phylogenetically and antigenically distinct serotypes (DENV-1-4) that cause outbreaks in humans and are also established sylvatic cycle infecting non-human primates. In the last decades, a strong increase in prevalence occurred in tropical and subtropical areas worldwide [1, 5]. Likewise, in Brazil, a growing number of cases are notified every year, and the country is experiencing hyperendemic DENV circulation [6, 7]. Since DENV reintroduction in the early 1980s, continuous reintroductions were reported for the four viral serotypes [8–10], allowing the persistence of intense viral circulation in Brazil. About 60% of all dengue cases reported worldwide are observed in Brazil [6].

DENV-2 has six genetically known genotypes: (i) American; (ii) American/Asian; (iii) Asian 1; (iv) Asian 2; (v) Cosmopolitan; and (vi) Sylvatic [11, 12]. Recently, a group of basal DENV-2 highly divergent sequences was reported, which was considered by some virologists and geneticists a new genotype within the serotype [13, 14]. In Brazil, the recently reported cases are of the American [7] and American/Asian genotypes [15, 16], the latter being known for its more severe clinical manifestations at the acute phase of infection [17]. The American/Asian genotype was introduced in the Americas coming from Asia during the early 1980s, spreading widely into the continent [16]. After 1990 the virus was reintroduced in Brazil, by different strains from the Caribbean region [15, 16, 18]. Brazil has experienced a sizeable increase in dengue cases associated with DENV-2 in 2019. Until June 2019 (epidemiological week 26), the number of notifications continued to rise, reaching 1,281,759 cases, and 443 deaths [19]. Here, we report clinical, pathological, virological, and genomic findings associated with a fatal case caused by DENV-2.

Case presentation

Clinical case description

At the end of April 2019, a 58-year-old man arrived at the emergency department complaining of 3 days of fever (38 °C), headache, myalgia, and arthralgia, with severe abdominal pain on the right upper abdomen, nausea, vomiting, and dehydration during the last 24 h. He had a past medical history of pulmonary tuberculosis treated in 2014 and B2 thymoma treated with chemotherapy and pleuropneumonectomy in 2017. During the first hours of observation, the patient developed hypotension, requiring vasoactive drugs, and was transferred to the intensive care unit. The initial laboratory tests showed Hb = 15.0 g/dL [Reference Range (RR) = 13–18 g/dL], HT = 43.3% (RR = 40–52%); peripheral blood total leukocytes = 5800/mm3 (RR = 4000-11,000/mm3); neutrophils count = 5200/mm3 (RR = 1600-7000/mm3); lymphocytes = 300/mm3 (RR = 900–3400/mm3); platelets = 9000/mm3 (RR = 150,000-450,000/mm3); urea 122 mg/dL (RR = 10–50 mg/dL); direct bilirubin 1,58 mg/dL (RR < 0,3 mg/dL); alanine aminotransferase = 91 U/L (RR < 41 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase = 270 U/L (RR < 37 U/L); creatine phosphokinase = 36 U/L (RR = 39–308 U/L); arterial lactate = 59 mg/dL (RR = 4.5–14.4 mg/dL). Abdominal ultrasound showed thickened gallbladder wall (measuring 0.9 cm), pericholecystic fluid collection, liquid in the parieto-colic gutter and pelvis, without gallstones and bile duct dilation. The abdominal tomography also showed the same findings. The initial clinical diagnosis was sepsis due to acalculous cholecystitis and ceftriaxone, metronidazol, platelets transfusion, fluids, antipyretic and analgesic medications were prescribed. An urgent exploratory laparotomy was performed, which showed an edematous gallbladder without signs of acute cholecystitis, and serohematic ascites without any other abnormalities. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, and evolved, in the postoperative period, with refractory shock, pronounced lactic acidosis, and multiple organ dysfunction. He was under mechanical ventilation, received vasoactive drugs and other standard intensive care measures. However, the patient died within 48 h of hospitalization. The autopsy was requested by the intensive medical care staff. The laboratory investigation ruled out yellow fever, leptospirosis, and rickettsia infection (Serology, RT-qPCR, and immunohistochemistry in liver tissue). All blood, ascites, and urine cultures were negatives.

Autopsy findings

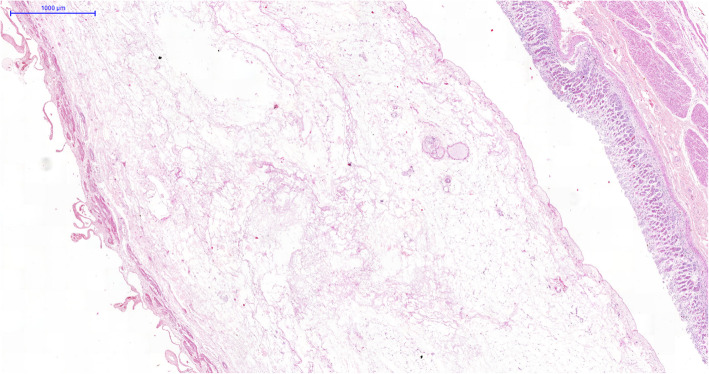

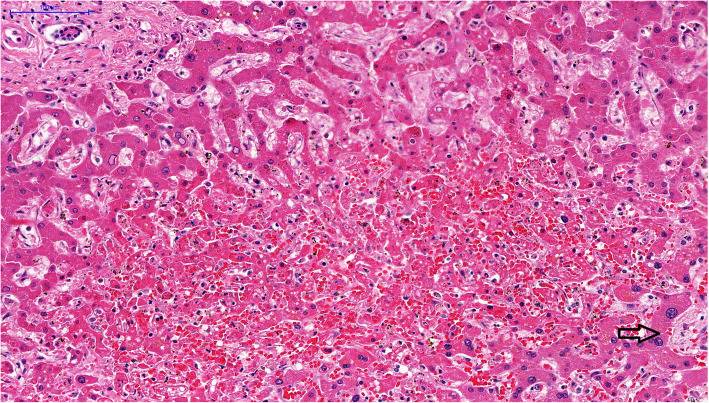

The main autopsy findings were: bilateral pleural effusion (with serohematic aspect, 1 l each side), ascites, bowel and gallbladder edema (Fig. 1), pulmonary edema and hemorrhage, and concentric left ventricular hypertrophy and atherosclerosis. The esophagus, stomach, and duodenum had hemorrhagic content, with diffuse mucosal bleeding. The liver weighed 906 g (RR = 1650 g) congested and diffusely steatotic. Tissue samples of 1 cm3 were collected from the main vital organs for molecular analysis. On microscopy, the liver presented midzonal hepatitis, with apoptotic and steatotic hepatocytes, Kupffer cell hyperplasia, sinus congestion, and hemorrhage, and mild inflammatory reaction, mainly composed of lymphocyte infiltrate (Fig. 2). Other findings were: foci of myocarditis, acute tubular injury, ischemic/reperfusion pancreatitis, spleen with lymphoid hypoplasia, splenitis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Fig. 1.

Intense interstitial edema in the gallbladder wall. HE 150x

Fig. 2.

Micrograph of the liver in a fulminant case of dengue fever: midzonal hepatitis, with apoptotic hepatocytes and sinusoidal congestion associated with a scarce inflammatory reaction. The portal area on the left top; arrow indicates centrilobular vein. HE 200x

Laboratory and phylogenetic investigation

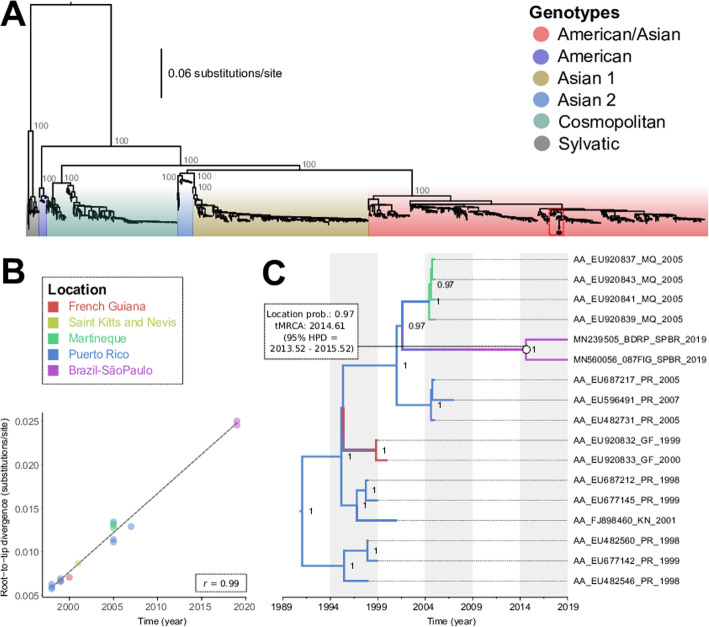

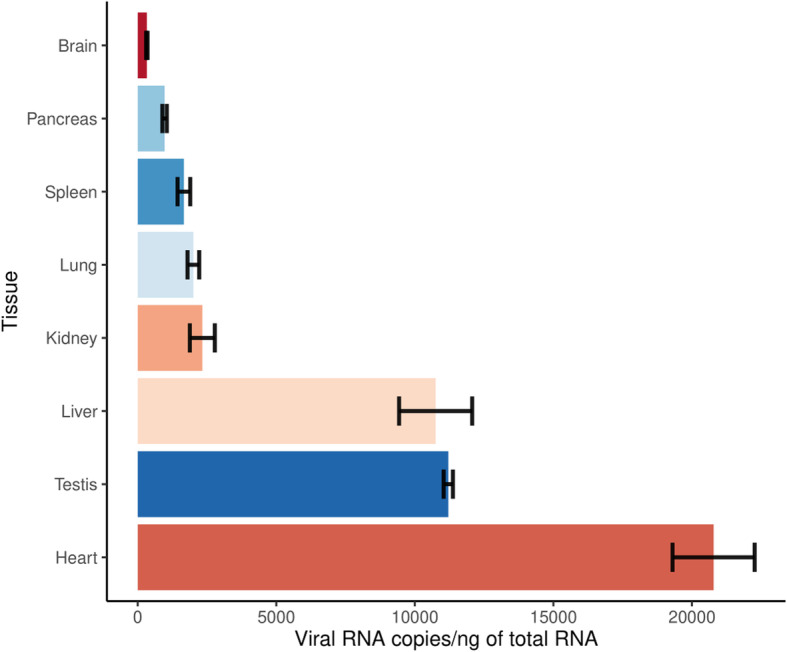

Molecular and serological results point to the patient as positively infected by DENV-2. All collected tissues were positive by RT-qPCR, indicating the presence of viral RNA in the tissues collected. The heart, testis, and liver had the highest amount of viral RNA (Fig. 3). The liver tissue was submitted to viral RNA sequencing, and the libraries were assembled and sequenced on the Illumina platform. The complete genome assembled with high coverage was from a DENV-2 serotype belonging to the American/Asian genotype, as indicated by a maximum likelihood tree (Fig. 4a). The sequence we characterized is closely related to another one also from Brazil and others previously isolated in Puerto Rico (2005–2007), Martinique (2005), and Guadeloupe (2006), available from GenBank. The two Brazilian sequences belong to a group not previously documented in Brazil, and possibly, constitute a new viral introduction from Puerto Rico that took place around 2014.61 (95% HPD = 2013.52–2015.52) (Fig. 4b-c).

Fig. 3.

Viral RNA concentration according to each of the 8 tissues analyzed for the patient. The different colors represent the different tissues analyzed, ordered by concentration values. The viral RNA quantification was done in triplicate, with the bar graph representing the average, and the intervals surrounding the mean represent the standard deviation. It is noticeable the high levels of viral RNA in the heart, testis, and liver

Fig. 4.

a Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees for DENV-2 based on full-length genome sequences (n = 879). The tree is midpoint-rooted and the values near the principal nodes represent statistical support values using the ‘ultrafast’ bootstrap approximation (UFboot) from IQ-TREE. Distinct colors represent different genotypes. The sequences used in phylogeography are marked with the dotted red square in the American/Asian genotype. The two Brazilian sequences isolated in 2019 are highlighted with the black circle. b A regression of root-to-tip genetic distance against the time of sampling and showing a positive relationship (r = 0.99) indicative of a high rate of evolutionary change over the sampling period. c Time-stamped, MCC tree of the DENV-2 American/Asian genotype associated with the Brazilian sequences isolated during 2019 (n = 17). The distinct colors represent samples from different locations. The values near the nodes represent posterior probability support

Discussion and conclusion

Usually, clinical manifestations associated with Dengue virus-induced infection vary from asymptomatic, unspecific acute febrile illness to severe dengue fever, which may progress to a fatal outcome [20–22]. By early August, 15,514 autochthonous cases were confirmed in São Paulo city, with 3 deaths and a 0.019 mortality rate [23]. In this regard, we describe a fatal autochthonous case, that occurred in the city of São Paulo, during the 2019 seasonal period caused by a new DENV-2 introduction, originating, most likely, from the Caribbean islands such as Puerto Rico, Martinique, and Guadeloupe. This case was noteworthy since it presented high viral RNA levels in several organs with significant signs of severe damage.

The patient came to the Clinical Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo (HC-FMUSP) during the critical phase of the infection, with warning signs such as serosal effusions, severe abdominal pain, and vomiting, due to plasma leakage, which usually occurs on the 4–6 day of illness [24]. Gallbladder edema and acalculous cholecystitis may be a major manifestation of severe dengue, mimicking an acute abdomen, masking the diagnosis of the disease. Ultrasound can detect acute acalculous cholecystitis and gallbladder edema, which occur in about 5–8% of dengue cases [20, 25], with a higher incidence in children [26]. Thick gallbladder wall has a positive association with Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever in a recent retrospective study conducted in Malaysia [20]. In general, the acalculous cholecystitis is accompanied by fever, Murphy’s sign, and ascites [26]. Without early fluid replacement, patients can evolve to an unfavorable outcome, with shock, as in the present case. The pathological features vary from intense edema of the gallbladder wall, as in our case, to mononuclear cells infiltrate, lymphoid follicle formation, and interstitial hemorrhages [21].

Viral RNA was detected on all collected tissues. This is in line with the previous detection of viral RNA in tissues, such as the kidney, heart, lung, and brain [27]. The concentrations of viral RNA found revealed the systemic spread of the virus to different organs associated with tissue damage. These observations were in line with previously reported lethal cases [28, 29].

Since its first report in Brazil [18], the American/Asian genotype vanished and was reintroduced a few times, always moving from Central America and the Caribbean to Brazil, following a pattern that was well documented for other Dengue serotypes [9, 10, 16]. As we characterize only 2 isolated sequences in the state of São Paulo, the date of introduction of the virus in Brazil we presented may be inaccurate. New sequences from other states, may help clarify this issue. Other studies indicated the circulation of this same virus in Rio de Janeiro and the west region of the state of São Paulo between 2018 and 2019 associated with the current outbreak [30, 31]. It has been argued that the viral genetic diversity in Puerto Rico tends to be maintained in situ, being driven by genetic drift with clade extinction and replacement events over time, with exchanges taking place with South and Central America and other Caribbean regions [32]. The intense movement of emerging viruses is mainly associated with the movement of asymptomatic infected humans and vectors, which is facilitated by rapid transport, such as air transportation [33].

Our results combined with other studies [30, 31] suggested a new DENV-2 introduction in Brazil, that may be associated with the phenomenon known as clade replacement that was demonstrated for other DENV lineages in different locations [16, 34–36]. Other than stochasticity, this could be explained by different factors, such as genetic differences in viral replication in vertebrate and/or invertebrate host [11], or possibly by the fact that herd immunity reduction against DENV-2, since it has not caused detectable outbreaks in Brazil during the last decade [9, 10, 37]. This fatal case associated with a new DENV-2 introduction in Brazil represents a small fraction when compared to classical dengue cases, and the systemic infection in the patient needs to be interpreted with caution, as it is a single-case study, and the patient has previous physiological disorders.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The author’s thanks to all physicians, residents, physiotherapists, nurses, and auxiliary-nurses who provided care to the patient; all residents of the Pathology Department who participated in the autopsy procedures; all technicians in our histology laboratory; and the relatives who agreed with the autopsy. We thank the Core Facility for Scientific Research – University of Sao Paulo (CEFAP-USP/GENIAL) for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- DENV

Dengue virus

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- RR

Reference Range

- HT

Hematocrit

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction quantitative real-time

- HPD

Highest posterior density

- HC-FMUSP

Clinical Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: MPC, ANDN, MD, PHNS, and PMAZ; Data curation: MPC, ANDN, SZP, LAH, FPF, MD, PHNS, and PMAZ; Formal analysis: MPC, ANDN, SZP, MD, PHNS, and PMAZ; Funding acquisition: MPC, PHNS, and PMAZ; Investigation: MPC, ANDN, SZP, LAH, FPF, MD, PHNS, and PMAZ; Methodology: MPC, ANDN, SZP, LAH, FPF and MD, PHNS and PMAZ; Project administration: MD, PHNS, and PMAZ. Resources: MPC, ANDN, SZP, LAH, FPF, MD, PHNS, and PMAZ; Software: MPC and ANDN; Supervision: MD and PMAZ; Validation: MPC, ANDN, and PMAZ. Visualization: MPC, ANDN, and MD; Writing – original draft: MPC, ANDN, and MD; Writing – review & editing: MPC, ANDN, SZP, LAH, FPF, MD, PHNS, and PMAZ. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the: Brazilian National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) process No. 441105/2016–5; the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) process no. 2017/23281–6; FAPESP process no. 2013/21728–2; FAPESP process no. 2020/04602-9; Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation INV‐002396, FunderDOI: 10.13039/100000865; and by the Fiocruz/Pasteur/Aucani-FUSP process no. 314502. MPC received a FAPESP fellowship no. 2016/08204–2. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All the datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The new sequence here characterized was deposited in GenBank under the accession number MN560056.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital (HC-FMUSP) (CAPPesq #426.643, CAAE protocol number: 18781813.2.0000.0068).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained for publication of this study by the patient’s family members.

Competing interests

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marielton dos Passos Cunha, Email: marieltondospassos@gmail.com.

Paolo Marinho de Andrade Zanotto, Email: pzanotto@usp.br.

References

- 1.Messina JP, Brady OJ, Scott TW, Zou C, Pigott DM, Duda KA, et al. Global spread of dengue virus types: mapping the 70 year history. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloria-Soria A, Armstrong PM, Turner PE, Turner PE. Infection rate of aedes aegypti mosquitoes with dengue virus depends on the interaction between temperature and mosquito genotype. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:480–496. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzman MG, Halstead SB, Artsob H, Buchy P, Farrar J, Gubler DJ, et al. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat Publ Gr. 2010;8:S7–16. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fares RCG, Souza KPR, Añez G, Rios M. Epidemiological Scenario of Dengue in Brazil. Biomed Res Int. 2015:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Villabona-Arenas CJ, Oliveira JL, Capra CS, Balarini K, Loureiro M, Fonseca CRTP, et al. Detection of four dengue serotypes suggests rise in hyperendemicity in urban centers of Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2620. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Costa RL, Voloch CM, Schrago CG. Comparative evolutionary epidemiology of dengue virus serotypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz-baez AS, Cunha MP, Vedovello D, Colombo TE, Nogueira ML, Villabona-arenas CJ, et al. Origin, tempo, and mode of the spread of DENV-4 genotype IIB across the state of São Paulo, Brazil during the 2012-2013 outbreak. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2019;114:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Cunha MP, Guimarães VN, Souza M, Cardoso DDP, Almeida TNV, Oliveira TS, et al. Phylodynamics of DENV-1 reveals the spatiotemporal co-circulation of two distinct lineages in 2013 and multiple introductions of dengue virus in Goiás, Brazil. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;43:130–4. 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Cunha MP, Ortiz-Baez AS, Freire CCM, Zanotto PMA. Codon adaptation biases among sylvatic and urban genotypes of Dengue virus type 2. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;64:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wei K, Li Y. Global evolutionary history and spatio-temporal dynamics of dengue virus type 2. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45505. doi: 10.1038/srep45505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Pickering P, Duchêne S, Holmes EC, Aaskov JG. Highly divergent dengue virus type 2 in traveler returning from Borneo to Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:2146–2148. doi: 10.3201/eid2212.160813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pyke AT, Huang B, Warrilow D, Moore PR, McMahon J, Harrower B. Complete genome sequence of a highly divergent dengue virus type 2 strain, imported into Australia from Sabah, Malaysia. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e00546–e00517. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00546-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueiredo LB, Sakamoto T, Coelho LFL, Rocha ESO, Cota MMG, Ferreira GP, et al. Dengue virus 2 American-Asian genotype identified during the 2006/2007 outbreak in Piauí, Brazil reveals a Caribbean route of introduction and dissemination of dengue virus in Brazil. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Mir D, Romero H, De Carvalho LMF, Bello G. Spatiotemporal dynamics of DENV-2 Asian-American genotype lineages in the Americas. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balmaseda A, Hammond SN, Pérez L, Tellez Y, Saborío SI, Mercado JC, et al. Serotype-specific differences in clinical manifestations of dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:449–456. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faria NRC, Nogueira RM, Filippis AMB, Simões JB, Nogueira FB, Lima MD, et al. Twenty Years of DENV-2 Activity in Brazil: Molecular Characterization and Phylogeny of Strains Isolated from 1990 to 2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Pan American Health Organization . Reported cases of dengue fever in the Americas by country of territory. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mallhi TH, Khan AH, Adnan AS, Sarriff A, Khan YH, Jummaat F. Clinico-laboratory spectrum of dengue viral infection and risk factors associated with dengue hemorrhagic fever: A retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1141-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estofolete CF, Mota MTO, Terzian AC, Milhim BHA, Ribeiro MR, Nunes DV, et al. Unusual clinical manifestations of dengue disease – real or imagined? Acta trop. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Estofolete CF, Terzian ACB, Parreira R, Esteves A, Hardman L, Greque GV, et al. Clinical and laboratory profile of Zika virus infection in dengue suspected patients: A case series. J Clin Virol. 2015;2016(81):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Município de São Paulo . Boletim arboviroses - Semana 33/2019. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilder-Smith A, Ooi EE, Horstick O, Wills B. Dengue. Lancet. 2019;393:350–363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu K, Changchien C, Kuo C, Chuah S, Lu S. Dengue fever with acute acalculous cholecystitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:657–660. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Setiawan MW, Samsi TK, Pool TN, Sugianto D, Wulur H. Gallbladder wall thickening in dengue hemorrhagic fever: an ultrasonographic study. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:357–362. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870230605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzmán MG, Alvarez M, Rodríguez R, Rosario D, Vázquez S, Valdés L, et al. Fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever in Cuba, 1997. Int J Infect Dis. 1999;3:130–135. doi: 10.1016/S1201-9712(99)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Limonta D, Capó V, Torres G, Pérez AB, Guzmán MG. Apoptosis in tissues from fatal dengue shock syndrome. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon T, Dung NM, Vaughn DW, Kneen R, Thao LTT, Raengsakulrach B, et al. Neurological manifestations of dengue infection. Lancet. 2000;355:1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres MC, Nogueira FB, Fernandes CA, Meira GLS, Aguiar SF, Chieppe AO, et al. Re-introduction of dengue virus serotype 2 in the state of Rio de Janeiro after almost a decade of epidemiological silence. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Jesus JG, Dutra KR, Sales FC, Claro IM, Terzian AC, Candido DD, et al. Genomic detection of a virus lineage replacement event of dengue virus serotype 2 in Brazil, 2019. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2020;115:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Allicock OM, Lemey P, Tatem AJ, Pybus OG, Bennett SN, Mueller BA, et al. Phylogeography and population dynamics of dengue viruses in the Americas. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1533–1543. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nunes MR, Palacios G, Faria NR, Sousa EC Jr, Pantoja JA, et al. Air Travel Is Associated with Intracontinental Spread of Dengue Virus Serotypes 1–3 in Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bruycker-Nogueira F, Mir D, dos Santos FB, Bello G. Evolutionary history and spatiotemporal dynamics of DENV-1 genotype V in the Americas. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;45:454–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Villabona-Arenas CJ, Zanotto PMA. Worldwide spread of dengue virus type 1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62649. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Villabona-Arenas CJ, Zanotto PMA. Evolutioary history of Dengue virus type 4: Insights into genotype phylodynamics. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:878–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Villabona-Arenas CJ, Oliveira JL, Sousa-Capra C, Balarini K, Fonseca CR, Zanotto PMA. Epidemiological dynamics of an urban Dengue 4 outbreak in São Paulo, Brazil. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1892. 10.7717/peerj.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The new sequence here characterized was deposited in GenBank under the accession number MN560056.