Abstract

Background

The outbreak of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is a public health crisis of global proportion. In psoriatic patients treated with biologic agents, evidence is not yet available on susceptibility to infection with the novel SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, and data about the perception of COVID-19 and its impact on these patients are lacking.

Aims

The aim of this observational, spontaneous study was the evaluation of the impact of anti COVID-19 measures in “fragile population” such as patients with a chronic inflammatory disease. Thus, we evaluated the impact of perceived risk on quality of life of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, in our outpatient clinic, and how their perceptions changed before and after the adoption of Covid-19 emergency measures following the Italian Ministerial Decree in March 9, 2020.

Methods

Using a series of questions, our study surveyed adult patients with moderate to severe psoriasis receiving treatment with biologic agents (n = 591), before and after the adoption of COVID-19 emergency measures.

Results

Most patients (97%) had been sufficiently informed by healthcare staff about COVID-19 spread. A significant change was observed in social activity reduction before and after the adoption of the measures (18% vs. 90% of patients; P < 0.0001). Similarly, patients were more likely to suspend ongoing therapy after the measures were adopted than before (87% vs. 34% of patients; P < 0.0001). Following the measures, older patients were significantly more inclined to suspend therapy and reduce social activities than younger patients.

Conclusions

Government COVID-19 emergency measures further curtailed already reduced social activities in psoriatic patients, and led to a greater inclination to suspend biologic therapy, more so in older patients, despite there being no evidence to support this suspension. These vulnerable patients may need support from clinicians in order to maintain treatment adherence.

Keywords: Biologic drugs, Coronavirus, COVID-19, Psoriasis, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Psoriasis is one of the most frequent chronic, recurrent, and inflammatory skin disease associated with significant comorbidity such as arthritis, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [1,2]. It affects around 2–3% of the population, and is characterized by a prevailing genetic susceptibility and autoimmune pathogenic features.

Around 10–20% of patients require systemic treatments [1].

In the past considered only a skin disease, the therapeutic approach for psoriasis was 37 based mainly on topical therapy, while in the most severe cases non-selective imunomodulators were used: corticosteroids, methotrexate, cyclosporineand retinoids [3].

At the onset of third millennium, the treatment of psoriasis has undergone significant changes. The use of new molecules, able to locking inflammatory mediators or their receptors, inhibiting the signaling path ways critically involved in psoriasis pathogenesis, has revolutionized the lives not only of psoriatic patients but also of dermatologists who treated them. Finally, patients could be offered total clearance of skin lesions and the suppression of the inflammatory process involving other organs and systems [3,4].

Both clinic aspect and quality of life were significantly influenced by these scientific results.

However, these highly effective therapies cannot be administered to all patients due to the danger of slippage of previous infection or the onset of an infectious disease during treatment. For these reason, patients must be screened before, but also periodically during treatment [5].

Screening includes investigations of Tuberculosis (TB), Hepatitis B and C and HIV.

Until March, 11th, 2020 when World Health Organization (WHO) proclaimed a pandemic state for coronavirus disease 19 (Covid-19), Western health care invested considerable efforts to combat chronic, oncological and inflammatory diseases [6].

Suddenly we were faced with a pandemic caused by a new and unknown virus, having to manage a new disease, but also, take care of chronic patients undergoing treatment with biologicals; so-called fragile subjects.

Even more, according to the ministerial decree of the Italian Ministry of Health, in order to contain the infectious risk, outpatient services have been allowed only for urgent visits or for short observation.

Psoriasis, as a chronic relapsing disease, was not one of these requirements.

Therefore, patients have had the right to withdraw their biological drug anti Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF alpha), or anti Interleukines (anti ILs)), but not to access the rutinary follow-up visit [7].

However, the risk of a hypothetical increased incidence of Covid-19 infection among this population, undergoing immunomodulating therapies, remains presently unknown. Moreover, data about the perception of the emergency by psoriatic patients and in particular those under biologic treatment, are still lacking [8].

For this reason we decided to contact all our database patients (610 subjects) suffering from moderate to severe psoriasis under treatment with anti-TNF alpha or anti-ILs, in order to get a more complete picture of the mood and the immunomodulating therapy they were using during the pandemic.

We conducted a survey based on an ad hoc questionnaire with eight questions. The first three queries concerned their consciousness about the novel viral spread, their state of awareness about Covid-19 and the sources from where they got the information.

The last questions, which focused on their social activities, the fear of becoming infected and the self decision to suspend the current therapy, were related to two different phases: before and after Italian Ministerial Decree, issued on 9 March 2020, with which the government declared the entire national territory a protected area, in an attempt to control infection transmission and decrease morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The study population included only patients of our outpatient services suffering from moderate to severe psoriasis and undergoing biologic therapy for at least the last six months. No correlation were made with other dermatologic patients.

The subjects both sexes were aged over 18.

From 610 patient contacted by phone call, 591 replied to the interview.

The first three questions concerned the general awareness of the current emergency situation were:

-

1)

Are you aware of the spread of the virus?

-

2)

What is your information source?

-

3)

Have you been sufficiently informed by the clinicians about COVID-19 prevention measures?

The last five questions concerned the attitude adopted by patients before and after the issuing of the restrictive Italian Ministerial Decree were:

-

4)

Have your social activity changed since the new health emergency emerged?

-

5)

Have your social activity changed after the Ministerial Decree?

-

6)

Were you scared of getting infected?

-

7)

Were you scared of getting infected after the declaration of the state of emergency?

-

8)

Have you thought about stopping your current therapy from the outset, or afterwards the declaration of the state of emergency

The answer modalities for each item were dichotomous: yes/no.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were described using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentage for dichotomous variables. Box plots were also used to represent continuous variables: lines represented the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers (error bars), the 10th and 90th percentiles.

The McNemar test was used to evaluate change before and after the adoption of COVID-19 emergency measures, in the following three variables: reduced social activities, fear of getting infected, and stopping current therapy.

The differences between age or gender and the variables of reduced social activities, fear of getting infected, and stopping current therapy, assessed after the adoption of COVID-19 emergency measures were evaluated with the Student’s t-test and chi-squared test, respectively.

P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R, version 3.6.1.

Results

The study population comprised 591 adult patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: 356 males (60.2%) and 235 females (39.8%); the average age was 58 years (SD 14). Diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis have had 290 (49,1%) of them, while 252 (42,6%) presented cardiometabolic comorbidities.

All patients were in receipt of therapy with biologic drugs as follows: 31.8% patients were receiving TNF-alpha inhibitors, 21.4% IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors, 12.7% IL-23 inhibitors, and 34.1% IL-17 inhibitors.

All patients expressed awareness about the spread of the novel coronavirus infection; 88.8% had learned about the spread through the internet, television and newspapers, and 11.2% through information provided by their general practitioner. Most patients (97%) reported that they had been sufficiently informed by healthcare staff.

In our survey, we observed that 43.5% (257/591) patients were not afraid of becoming infected, whereas 56.5% (334/591) were before the adoption of the restrictive health measures, while we predictably discovered that 100% of patients were afraid of contracted the virus after the ministerial decree.

We evaluated how the behavior of our psoriatic patients changed before and after the adoption of the emergency measures for COVID-19 spread.

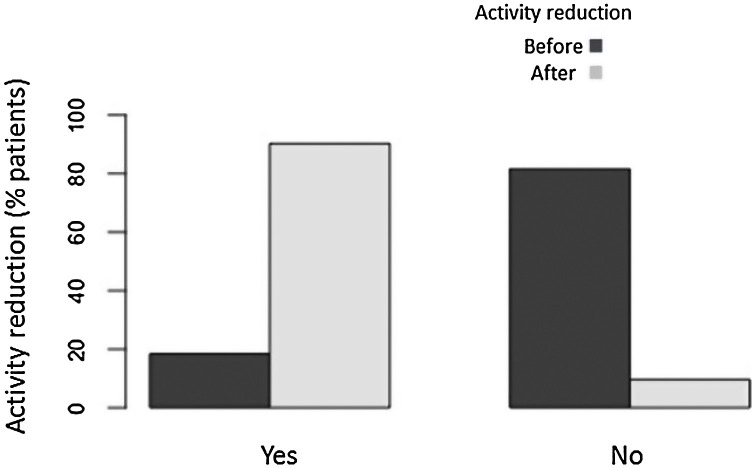

Most patients who had not reduced their social activity before the COVID-19 emergency measures did so after the emergency measures were adopted (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

A statistically significant change was observed in terms of reduction of social activities before (18.4% of patients) and after (90.0% of patients) the adoption of the emergency measures, according to the McNemar test (P < 0.0001).

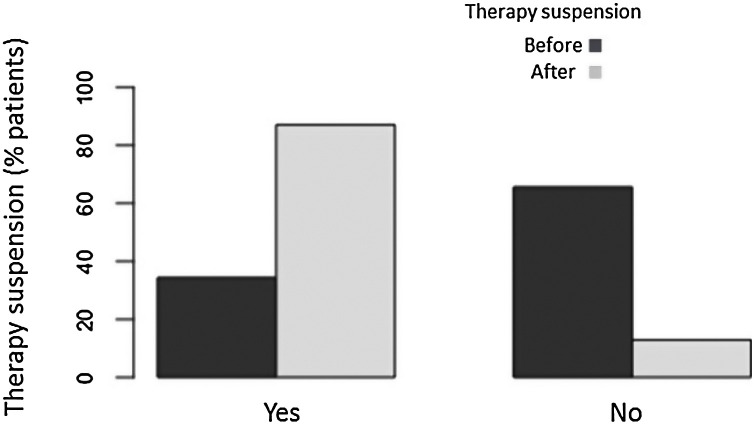

Furthermore, we observed that patients had a greater propensity to suspend therapy after the emergency measures were adopted (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

The McNemar test highlighted a significant difference in the voluntary decision to suspend current therapy before (34.4% of patients) and after (87.1% of patients) the adoption of COVID-19 emergency measures (P < 0.0001).

No significant differences were observed regarding gender in patients who reduced social activities after the measures’ adoption.

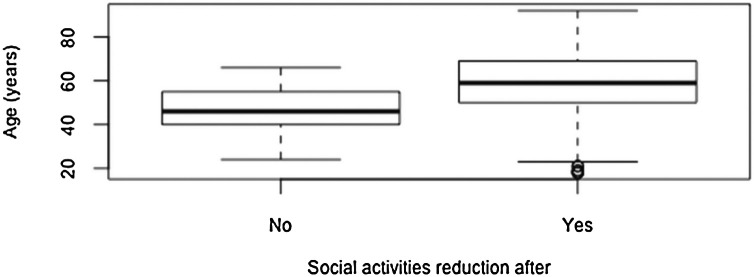

Patients who did not reduce social activities after adoption were, on average, of a younger than those who did reduce their activities: 46.9 years (SD 10.0) and 58.8 years (SD 14.2), respectively (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

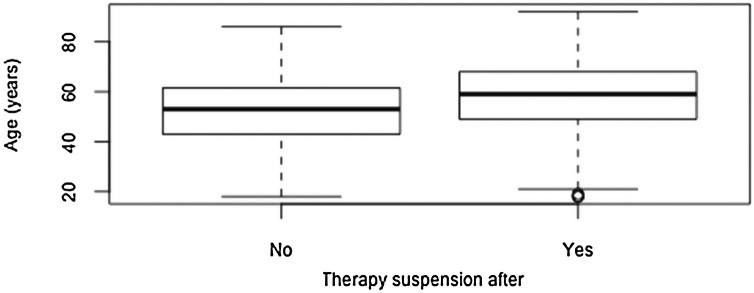

The mean age of the group who did not consider to suspend the ongoing therapy following adoption of emergency measures (52.7 years, SD 14.3) was significantly lower than that of the group who did suspend therapy (58.3 years, SD 14.1; P = 0.002; Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Young patients were more inclined to continue the biological therapy but we observed (for all age groups) a certain percentage of cases (15% of patients) who decided to defer the farmacological dose autonomously.

Discussion

Psoriasis is a multifactorial inflammatory skin disease, with a chronic relapsing course [9]. The psoriatic inflammatory state may extend beyond the skin to involve other organs (heart, bones, liver); moreover, recently, some studies report the possibility that psoriasis may affect the lungs, an effect likely to be defined as a new comorbidity [10].

Currently, the dissemination of COVID-19 is affecting people worldwide. COVID-19 predominantly induces a lower respiratory tract disease, identified as a novel coronavirus pneumonia; means of COVID-19 transmission include respiratory infection control include early detection of infected people, maintenance of social distancing and quarantine [12].

In this new paradigm, the need to reduce social contacts, concomitant with the fear of contagion, could have different repercussions on patients quality of life.

In this context, our survey investigated the impact of perceived risk on the quality of life of 591 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis attending our department and, moreover, how this perception changed before and after the adoption of COVID-19emergency measures following the prime ministerial decree in March 2020.

Although it has been reported in the literature that in psoriatic patients who contract the covid-19 infection there is a worsening of the clinical picture, our aim was only to assess the impact of the pandemic on the quality of life in psoriatic patients [13].

We found that all patients were conscious of the spread of the coronavirus infection and nearly all reported that they have been sufficiently informed by healthcare staff.

Just over half of our patients were afraid of contracting the novel coronavirus in the survey interval prior to adoption of the restrictive health measures but, predictably, all patients become afraid after the emergency measures were announced. These data, which may appear inevitable and obvious, however, emphasize the significant frailty of these patients with chronic psoriasis.

A high percentage of our patients reduced their social activities after hearing about the novel health crisis; this trend was increased after the adoption of COVID-19 emergency measures. Younger subjects were less likely to suspend their usual social activities than older patients, probably because older patients feel more fragile and vulnerable due to potential, concomitant pathologies, polypharmacy, and iatrogenic effects [14].

We observed that only a few patients intended to suspend their ongoing biologic therapy voluntarily in the early stage of the health crisis.

Nevertheless, we detected a tendency to defer the pharmacological dose independently, for all age groups.

This could be explained as a need to keep psoriatic symptoms under control and not negate any progress achieved.

It is well known that psoriasis has a significant impact on patient quality of life in which the fear of getting worse is very present [15]. Overall, patients were more inclined to suspend their therapy following the adoption of emergency measures; this inclination was more evident in older patients than younger patients. Despite no scientific evidence currently supporting the potential interference of biologic agents on the pathogenesis of the novel coronavirus, clearly, clinicians cannot oppose their patients’ willingness to interrupt therapy.

Although it is well known that Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores in females with psoriasis are significantly higher than in males, we didn’t observe any gender differences in this study [15].

Although some studies report the possibility that psoriasis may affect the lungs; to date, lung involvement and respiratory comorbidities in psoriasis has been poorly investigated. Nevertheless, recent studies report the concurrent persistence of psoriasis and interstitial pneumonia (IP), but the relationship and the common pathways shared between these two diseases has not yet been clarified [[16], [17], [18], [19]].

A recent study described the presence of mild asymptomatic IP in 2% of patients with severe psoriasis, in therapy with biologic drugs [20]. In addition, the rate of IP exacerbation varied in parallel with psoriasis severity suggesting that common mechanisms sustain both skin and lung lesions. It was suggested that IL-12, IL-23, and IL-17 might play an important role in the pathogenesis of both diseases, although a clear role for this pathway remains to be elucidated [21].

Given this association, a future goal will be to record the incidence and prevalence of the novel coronavirus infection in psoriatic patients undergoing biologic therapy. In act, with the introduction of biologic drugs in the 2000s (TNF-alpha inhibitors initially and interleukin inhibitors later), psoriasis became an ideal model for the study of these agents. In particular related to their beneficial effects on the disease and its comorbidities, on patient quality of life, but also on the greater susceptibility of exacerbation of latent or occult infections.

Our real-life data demonstrate that patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing therapy with biologics are cognizant of the spread of the novel coronavirus infection and fearful of becoming infected. The adoption of government COVID-19 emergency measures further curtailed already reduced social activities in this vulnerable patient population and led to a greater inclination to suspend biologic therapy, more so in older patients, despite there being no evidence to support such a suspension.

Currently clinicians still have limited data for decide whether to continue biologic therapy during pandemics and it should still be established if biologics could render patients more susceptible to coronavirus.

Elmas et al. declare that in the pre-coronavirus era, respiratory infection rates were comparable to those with placebo [8].

Besides, biologic therapies discontinuation could result in loss of response when treatments are reintroduced or may lead to a development of antibodies against the discontinued biologic drugs [22].

All of these factors must be considered when advising patients about continuing or discontinuing biologic therapies.

However, recently the Italian society of Dermatology and Venereology, as well as other major International Scientific Communities, states that in the absence of clinical and laboratory signs of Covid 19 infection, it is not necessary to stop biological systemic therapies for chronic inflammatory dermatosis such as psoriasis [23].

To date, there are no evidences that biologics could lead to an increased risk of Covid-19 infection. Instead, unnecessary biologic discontinuation could be reason for worsening of psoriasis and quality of life burden [13].

Indeed, it seems that the control of TNFalpha and other cytokines production could contribute to a less aggressive organic response to SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, the inhibition of IL-17 pathway may have beneficial effects in treating COVID-19 [24].

In conclusion, the clinicians that are more familiar with biologic therapies might give a more effective support for chronic and fragile patients, in order to reassured them and help them to maintain treatment adherence.

Funding

No funding sources.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Acknowledgements

We confirm that none organizations funded our research.

References

- 1.Rendon A., Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proietti I., Raimondi G., Skroza N., et al. Cardiovascular risk in psoriatic patients detected by heart rate variability (HRV) analysis. Drug Dev Res. 2014;75(Suppl. 1):S81–S84. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardini N., Skroza N., Tolino E., et al. Benefit of a topic ointment as co-medication with biologic drugs for the management of moderate-severe psoriasis: a prospective, observational real-life study. Clin Ter. 2020;171(4):e310–e315. doi: 10.7417/CT.2020.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psoriasis Agents . National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda (MD): 2012. LiverTox: clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steuer A.B., Wang J.F., Feng H., Cohen J.M. Systemic treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: a cross sectional study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 26] J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1795059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lake M.A. What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20:124–127. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2019-coron. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebwohl M., Rivera-Oyola R., Murrell D.F. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmas Ö.F., Demirbaş A., Kutlu Ö., et al. Psoriasis and COVID-19: a narrative review with treatment considerations [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 17] Dermatol Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1111/dth.13858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schleicher S.M. Psoriasis: pathogenesis, assessment, and therapeutic update. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2016;33:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado-Pinto J., dos Santos Diniz M., Couto Bavoso N. Psoriasis: new comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:8–16. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun P., Lu X., Xu C., et al. Understanding of COVID-19 based on current evidence. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Megna M., Napolitano M., Patruno C., Fabbrocini G. Biologics for psoriasis in COVID-19 era: what do we know? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(July (4)):e13467. doi: 10.1111/dth.13467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billon R., Thomas P. Elderly and frail patients with polymorbidities: what quality of life? Soins Gerontol. 2019;24:22–24. doi: 10.1016/j.sger.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mabuchi T., Yamaoka H., Kojima T., et al. Psoriasis affects patient’s quality of life more seriously in female than in male in Japan. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:84–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santus P., Rizzi M., Radovanovic D., et al. Psoriasis and respiratory comorbidities: the added value of fraction of exhaled nitric oxide as a new method to detect, evaluate, and monitor psoriatic systemic involvement and therapeutic efficacy. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3140682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen P.R., Isaksen J.L., Jemec G.B., et al. Pulmunary function in patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional population study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:518–519. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta R., Espiritu J. Azathioprine for the rare case of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in patients with psoriasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1248–1251. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201505-274LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penizzotto M., Retegui M., Arrién Zucco M.F. Organizing pneumonia associated with psoriasis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46:210–211. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamoto H., Hara H., Minagawa S., et al. Interstitial pneumonia in psoriasis. Mayo Clin Proc Inn Qual Out. 2018;2:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hara H., Kuwano K., Kawamoto H., Nakagawa H. Psoriasis-associated interstitial pneumonia. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28:395–396. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2018.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Hammadi A., Ruszczak Z., Magariños G., Chu C.Y., El Dershaby Y., Tarcha N. Intermittent use of biologic agents for the treatment of psoriasis in adults [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 8] J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micali G, Musumeci ML, Peris K, Board Members of the SIDeMaST. The Italian dermatologic community facing COVID-19 pandemic: recommendation from the Italian society of dermatology and venereology. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bardazzi F., Loi C., Sacchelli L., Di Altobrando A. Biologic therapy for psoriasis during the covid-19 outbreak is not a choice. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(June (4)):320–321. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1749545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

[11] Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. medRxiv 2020; Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974.