Abstract

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disease associated with severe exocrinopathy, which is characterized by profound lymphocytic infiltration (dacryoadenitis) and loss of function of the tear-producing lacrimal glands (LG). Systemic administration of Rapamycin (Rapa) significantly reduces LG inflammation in the male Non Obese Diabetic (NOD) model of SS-associated autoimmune dacryoadenitis. However, the systemic toxicity of this potent immunosuppressant limits its application. As an alternative, this manuscript reports an intra-LG delivery method using a depot formulation comprised of a thermo-responsive Elastin-Like Polypeptide (ELP) and FKBP, the cognate receptor for Rapa (5FV). Depot formation was confirmed in excised whole LG using cleared tissue and observation by both laser-scanning confocal and lightsheet microscopy. The LG depot was evaluated for safety, efficacy, and intra-LG pharmacokinetics in the NOD mouse disease model. Intra-LG injection with the depot formulation (5FV) retained Rapa in the LG for a mean residence time (MRT) of 75.6 hr compared to Rapa delivery complexed with a soluble carrier control (5FA), which had a MRT of 11.7 hr in the LG. Compared to systemic delivery of Rapa every other day for 2 weeks (7 doses), a single intra-LG depot of Rapa representing 16-fold less total drug was sufficient to inhibit LG inflammation and improve tear production. This treatment modality further reduced markers of hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia while showing no evidence of necrosis or fibrosis in the LG. This approach represents a potential new therapy for SS-related autoimmune dacryoadenitis which may be adapted for local delivery at other sites of inflammation; furthermore, these findings reveal the utility of optical imaging for monitoring the disposition of locally-administered therapeutics.

Keywords: Sjögren’s syndrome, Elastin-Like Polypeptide, Rapamycin, Depot formulation, Lacrimal gland, Intra-lacrimal delivery, Non-obese Diabetic Mouse, Dry Eye

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal glands (LG) and salivary glands (SG) and the consequent reduction in tear and saliva production, respectively1, 2. These changes can lead to severe corneal damage and compromised oral health. SS patients can develop additional systemic symptoms including inflammation of other internal organs such as brain, lung and liver as well as, in a subset of patients, B-cell lymphoma3. SS is classified as primary (pSS) when the clinical manifestations occur alone, or as secondary (sSS) when associated with another autoimmune disease, usually a connective tissue disease. The estimated incidence rate of pSS is 7 /100,000 person-year, and the overall prevalence is 61 cases/100,000 inhabitants, although the incidence and prevalence are likely underestimated since many symptoms are nonspecific4. The LG produces the aqueous component of the tear film, as a result, inflammatory damage of the LG leads to aqueous-deficient dry eye disease, treatment of which is our experimental focus.

The first line therapy for aqueous-deficient dry eye disease is artificial tears, a replacement therapy which increases the volume of the tear film and the residence time of tears on the ocular surface. Providing only temporary relief of ocular symptoms, artificial tears fail to inhibit the underlying inflammation related to autoimmunity that is present both on the ocular surface and in the LG. Anti-inflammatory therapies such as topical corticosteroids, cyclosporine eyedrops, and lifitegrast eyedrops are also used for clinical management of dry eye symptoms, though each has disadvantages. Long term use of corticosteroids is complicated by the emergence of cataracts, glaucoma, and infection5. Cyclosporine can cause ocular surface pain, irritation and a burning sensation, leading to low patient compliance and premature discontinuation of medication6. Clinical trials of lifitegrast in dry eye patients have shown mixed therapeutic effects7–9. Previously, our group has shown that Rapamycin (Rapa), an FDA-approved immunosuppressant, when formulated as an eyedrop for twice daily administration significantly inhibited LG inflammation and increases tear production over a 12 week treatment window in male Non-obese Diabetic (NOD) mice, a commonly-used mouse model which manifests the ocular symptoms of SS10. However, topical administration of Rapa resulted in inefficient recovery in the LG, the primary target for reducing autoimmune exocrinopathy. Here, we have developed a sustained-release formulation of Rapa for local administration to the inflamed LG with the help of Elastin-Like Polypeptides (ELPs).

ELPs are thermo-responsive protein polymers consisting of different repeats of (Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly)n pentamers where the guest residue, Xaa, specifies any amino acid and n determines the number of pentapeptide repeats. ELPs can undergo a temperature-dependent reversible inverse phase transition wherein they remain soluble below their transition temperature (Tt) and form a coacervate above Tt11–13. Taking advantage of this property, ELPs can be easily purified by several rounds of heating and cooling without addition of any extra purification tags. ELPs can be precisely genetically engineered and are biocompatible, biodegradable, of low immunogenicity, and environmentally-responsive, which has enabled their diverse applications in drug delivery12, 14, 15. Tt can be finely tuned by adjusting the hydrophobicity of the guest residue and the number of pentameric repeats. In general, ELPs with high molecular weight and/or hydrophobic guest residues exhibit lower transition temperatures than ELPs with low molecular weights and/or hydrophilic guest residues16. FK-506 binding protein 12 (FKBP), the cognate human receptor for Rapa, was genetically fused onto different ELPs to generate a Rapa drug carrier, without impairing the thermo-responsiveness of the ELPs17. Previously we have shown that when delivered systemically by FKBP-ELP, Rapa could significantly inhibit LG inflammation and improve ocular surface symptoms in diseased male NOD mice17, 18. However, the frequent dosing interval used in these studies, as well as the systemic toxicity related to Rapa such as hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia were drawbacks in clinical translation of this strategy.

Here, taking advantage of the temperature responsive property of ELPs, we have developed a high capacity ELP carrier for Rapa with a Tt below physiological temperature which forms a depot loaded with Rapa at the injection site. We then tested its efficacy in SS-related autoimmune dacryoadenitis in the male NOD mouse model. To accomplish this, we selected valine, a hydrophobic amino acid, as the guest residue and generated [FKBP-(VPGVG)24]4-FKBP(5FV), which is theoretically capable of carrying five Rapa molecules per carrier and also has a relatively low Tt. We also made [FKBP-(VPGAG)24]4-FKBP(5FA) as a soluble control carrier for comparison of tissue retention times after intra-LG delivery. For this control construct, the less hydrophobic amino acid, alanine, was selected as the guest residue, which has a relatively high Tt. We hypothesized that direct injection of 5FV-Rapa into the LG would generate a depot which could be monitored utilizing diverse imaging approaches, and which would achieve sustained release of Rapa into the LG to achieve therapeutic affects at a reduced dosing interval, while minimizing the systemic toxicity of Rapa.

Material and Methods

Reagents

BLR(DE3) competent E. coli was from New England BioLabs Inc. (Ipswich, MA, USA). Rapamycin (Rapa) was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). TO-PRO™-3 Iodide (642/661) and NHS-Rhodamine were from ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL,USA). Carbachol, used to stimulate tear production, was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ketamine (Ketaject) was from Phoenix (St. Joseph, MO, USA) and xylazine (AnaSed) was from Akorn (Lake Forest, IL, USA). Zeba™ Spin Desalting Columns, 7K MWCO (10 mL) were from ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL, USA). Sulfo-Cyanine 7.5 NHS ester was from Lumiprobe Corp (Hallandale Beach, FL, USA). ZoneQuick phenol red threads were from SHOWA YAKUHIN KAKO CO., LTD (Tokyo, Japan). Free Style Lite test strips were from Abbott Diabetes Care, Inc. (Alameda, CA, USA). Other reagents were from standard suppliers.

Molecular Cloning

5FA and 5FV were cloned using standard restriction enzyme-based cloning. The cloning schematic is shown in Figure S1. The pIDTsmart vector with the FKBP oligonucleotide sequence was ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA,USA) with three restriction cut sites flanking the FKBP gene: NdeI, BserI at the 5’ end and BamHI at the 3’ end. This vector was digested with NdeI and BamHI and the gel-purified FKBP gene was inserted into a pET25b (+) vector digested with the same set of enzymes. Next, pET25b (+) containing the FKBP gene and a modified pET25b (+) vector (mPET) containing the (VPGAG)24 (A24) were double-digested with BserI and BssHII. The appropriate gene containing fragments was gel purified and ligated to generate an intermediate vector containing the FKBP-A24 (FA) fusion gene. Following double digestion of this intermediate vector with NdeI and BamHI, FA was purified and inserted into an empty mPET vector that was digested with the same set of enzymes. FA (mPET) was double-digested with two sets of enzymes: BserI + BssHII and AcuI + BssHII. The appropriate fragments containing FA were purified and ligated to generate FAFA (in the mPET vector). This was repeated using FAFA (mPET) to generate FAFAFAFA. Finally, addition of FKBP at the 3’ end of FAFAFAFA was performed as previously described19 to generate FAFAFAFAF(5FA). The same protocol was used to clone FVFVFVFVF (5FV) by using the (VPGVG)24 (V24) sequence instead of A24. FAF was cloned as previously described19.

ELP Purification, Characterization and labeling

5FA, 5FV and FAF were purified using three rounds of Inverse Transition Cycling (ITC) as described previously18. Fusion protein polymers were analyzed for purity by SDS-PAGE gel analysis and Coomassie blue staining. The temperature-concentration phase diagram was determined as previously described20, 21. Briefly, absorbance at 350 nm was measured in a DU800 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, CA,USA) under a temperature gradient of 0.3°C/min. The transition temperature at each concentration of ELP was defined as the temperature at which the maximum first derivative was achieved within each optical density profile with respect to the temperature. The transition temperature from each concentration was used to plot the phase diagram and fit with Equation 1:

| (1) |

For fluorescent visualization after intra-LG injection, 5FA or 5FV were covalently modified with NHS-Rhodamine. Excessive dye was removed by Zeba™ Spin Desalting Columns, 7K MWCO (ThermoFisher Scientific) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

5FA and 5FV were immobilized on the surface of a Series S Sensor Chip CM5 (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) at pH 4.5 by amine coupling using 1-ethyl-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and NHS to a final density of 15000 response units (RU). Residual sites on the dextran were blocked with 1 M ethanolamine hydrochloride. A control flow cell was blocked with ethanolamine for reference subtraction. Experiments were performed in running buffer (0.1 M HEPES, 1.5 M sodium chloride, 30 mM EDTA and 0.5% Surfactant P20, 1% DMSO, pH 7.4). Dilutions of Rapa dissolved in running buffer were injected over the chip at 20 mL/min for 2 min. The proteins were then dissociated from the chip for 2.5 min with running buffer. The remaining protein was removed from the chip by 0.05% SDS at 30 mL/min for 30 s followed by 1 mM sodium hydroxide at 30 ml/min for 30 s. Sensorgrams were generated and analyzed using Biacore T100 Evaluation Software (version 2.0.2). The equilibrium RU observed for each injection was plotted against the concentration of protein. The equilibrium Ka, Kd and KD values were derived by analysis of the plots using the steady-state affinity model.

Rapamycin Encapsulation

5FA or 5FV in PBS was mixed with a 10X molar access of Rapa dissolved in 100% ethanol. The vial was stirred at 4°C for 2–3 hrs. Excess drug was removed by centrifugation at 13.2K RPM, 20 min followed by filtration through a 0.2 μm syringe filter. Residual organic solvent was further removed by overnight dialysis with a cut-off molecular weight of 10 kDa. To determine the amount of encapsulated drug, the sample was injected into a C-18 reverse phase HPLC column and eluted in a water: methanol gradient from 40% to 100%. Rapa concentration was calculated using a standard curve.

Animal Procedures

C57BL/6J breeding pairs and male NOD mice aged 12 weeks old were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were bred in the University of Southern California (USC) vivarium. All animal procedures were approved by the USC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance to the guide for care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed22. For intra-LG injection (Figure S2), fur was removed from the cheek using a pet razor and the area cleaned with three changes of povidone iodine and alcohol after mice were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine + 10 mg/kg xylazine and placed on a heating pad. A small incision (5 mm) was made to visualize the LG. ELP-rapamycin or ELP were injected into the LG on both sides using a 35-gauge blunt needle. The incision was closed with GLUture® Topical Tissue Adhesive(Zoetis Inc., Kalamazoo, MI, USA). Buprenorphine SR (0.5–1mg mg/kg) was given subcutaneously to relieve any pain from the surgery. The mice were placed on a heating pad and monitored until they were fully recovered from anesthesia. The animals were monitored daily post-op for any signs of pain stress or infection. For LG collection, LGs were removed after mice were euthanized via intraperitoneal injection with 55 mg Ketamine and 14 mg Xylazine per kilogram of body weight, followed by cervical dislocation.

Tissue Clearing and Confocal Microscopy

A single injection of 5 μl of Rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa or 5FV-Rapa were injected into both LG of C57 mice aged 13 weeks old for optimized visualization of the depot. The LG were collected the next day and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight. Tissue clearing was done with an adapted protocol from “3D imaging of solvent cleared organs” (3DISCO)23. In brief, LGs were washed 3 times in PBS before permeabilization with 1% Triton X-100 for 1 hr at room temperature the next day. Then the LG were stained with TO-PRO™-3 Iodide (642/661) at 4°C overnight. LGs were washed 3 times with PBS the next day followed by dehydration in series of ethanol solutions (ranging from 50% to 100% ethanol in water). After that, LGs were placed in 100% hexane for 2 hr at room temperature to remove any trace amounts of water. Then LGs were placed in BABB solution (benzyl alcohol: benzyl benzoate=1:2) for clearing with close monitoring. After the LG became transparent, they were stored in ethyl cinnamate for further imaging. Cleared glands were imaged using a ZEISS LSM 800 confocal microscope equipped with an Airyscan detector (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). A Z-stack of 25 pictures at intervals of 3 μm was taken and converted into a video format.

Lightsheet Microscopy and Image Processing

Cleared glands were also imaged using a lightsheet microscope. Lightsheet data were collected on an M-Squared (M-2) Aurora microscope (https://www.m2lasers.com/microscopy-aurora). The samples and objectives were immersed in ethyl-cinnamate for index matching with the BABB cleared tissue preparation. Samples were imaged with 594 nm (2% laser power, 10 ms exposure) and Hoechst Far-red with 647 nm (1% laser power, 4 ms exposure) diode laser lines. LG with Rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa was collected as a 5X5 tile scan and LG with Rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa as a 4X6 tile scan. The Airy beam design of the Aurora requires deconvolution to produce isotropic resolution. A deconvolution standard was produced by embedding multi-color silica beads in 2% low-melt agarose. This hydrogel was dehydrated in washes (2 hrs each) of increasing ethanol concentration (1×25%, 1×50%, 1×75%, 2×95%, 2×100%) and the final dehydration steps were in 2× 2 hr washes in 100% methanol. The dehydrated gel was washed once in ethyl-cinnamate overnight and transferred into 100 ml of fresh ethyl-cinnamate for storage in the immersion medium for imaging the calibration standard. M-2 Deconvolution software processed both samples using 100 iterations of the Richardson-Lucy deconvolution algorithm. The deconvolution step also prepares the 3 dimensional tiles for stitching. 3-D, 2 channel tiles were converted into .ims file format in Bitplane’s Imaris File Converter for stitching in Imaris Stitcher and all animated movies/snapshots were produced in Imaris v9.6.0.

Safety Evaluation of Intra-LG Injection

Male C57 mice aged 12–14 weeks old were injected intra-LG with 32 μl of 5FA or 5FV (366 μM) in total, 16 μl per side with 4 injections of 4 μl each. Mice without injections were used as nontreated controls. Mice were euthanized 2 weeks after injection and the LG were collected for immunofluorescence staining, H&E staining and Trichrome staining, per established procedures.

Intra-LG Pharmacokinetics Study after Intra-LG Injection

C57 mice aged 12–14 weeks were injected intra-LG with 32 μl of 5FA or 5FV (1.2 mM Rapa, 366 μM ELP) in total, 16 μl per side with 4 injections of 4 μl each. Each group included 2 male mice and 2 female mice. The amount of Rapa in the LG was assessed at 2 days, 1 week and 2 weeks after injection using LC-MS following the protocol previously reported21. Mean residence time (MRT) is calculated from Equation 2:

| (2) |

Where AUMC and AUC stand for Area under the Moment Curve and Area under the Curve, respectively, and are estimated with the trapezoidal method.

Therapeutic Study

The protocol for this study is shown in Figure 1. 12 μl of 5FV-Rapa (1.2 mM Rapa, 0.44 mg/kg, 366 μM 5FV) was injected using intra-LG injection into 13 week diseased male NOD mice in total, 6 μl per each LG in 3 injections of 2 μl each. This lower volume was chosen to avoid excessive swelling of the LG. The same volume of PBS was injected into using the identical procedure as a negative control. FAF-Rapa (1 mg/kg) was injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in the thigh every other day for two weeks as a systemic administration control which was previously shown to be effective and sufficient to reduce lymphocytic infiltration of the LG24. Mice receiving FAF-Rapa s.c. injections also received a single PBS intra-LG injection comparably to the 5FV-Rapa group to control for any intra-LG injection effects. The accumulated doses for 5FV-Rapa and FAF-Rapa were 0.44 mg/kg and 7 mg/kg, respectively. Basal tear production and blood glucose was measured before and two weeks after treatment. All the mice were euthanized as described above for further analysis.

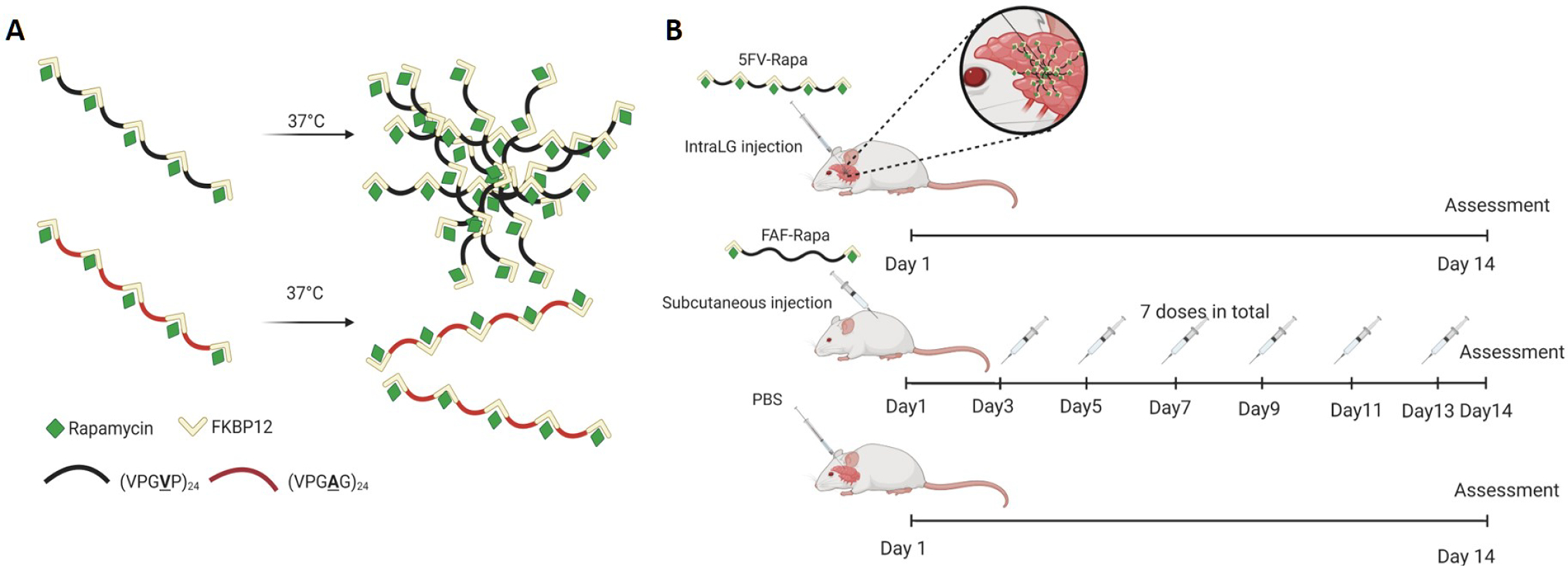

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of intra-LG injection of 5FV-Rapa relative to subcutaneous administration of a soluble Rapa carrier, FAF.

A) Graphical illustration of depot formation by 5FV-Rapa but not 5FA-Rapa. B) Schematic illustration of the study evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of a single intra-LG injection of 5FV-Rapa (0.44 mg Rapa/kg × 1 dose) versus subcutaneous injection every other day of FAF-Rapa (1mg Rapa/kg × 7 doses), a systemic administration control, over 14 days in diseased male NOD mice. A control treatment was intra-LG with PBS on Day 1 of the two week study, also shown. Created with biorender.com.

Basal and Stimulated Tear Measurements

Basal and stimulated tears were measured as described24. Briefly, for measurement of basal tear flow, a ZoneQuick phenol red impregnated cotton thread was inserted under the lower eyelid for 10 sec while mice were under anesthesia, and tear production was reported as a function of the length of wetting of the thread in millimeters. Data is plotted by values obtained from each individual eye, so each mouse contributes two thread measurements. For collection of stimulated tear fluid, a small incision was made to expose the LG of anesthetized mice. A small piece of cellulose mesh (Kimwipe; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was placed on the LG to capture added secretagogue (3 μl of 50 μM carbachol solution). After stimulating the gland for 5 min, tears from both eyes were collected with 2 μl microcapillary tubes (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA, USA.) Stimulation was performed three times for a total collection time of 15 min, and the volume of collected tears was recorded. Tears were stored on ice until further biochemical analysis.

Blood Glucose and Lipid Measurements

Mice in the non-fasting state were anesthetized briefly using a continuous flow of isoflurane through a nose cone. A tail nick was made, and a drop of peripheral blood was collected. Blood glucose levels were measured using Free Style Lite test strips and a glucose meter (Abbott Diabetes Care, Inc., Alameda, CA,USA). For serum chemistry, blood collected via cardiac puncture at the conclusion of the study was centrifuged (2000 rcf, 10 min, 4 °C) to separate serum and outsourced for measurements of blood lipids on the day of collection using a commercial provider.

Histology Analysis of LGs

Mice were euthanized and LGs were removed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin prior to embedding in paraffin blocks. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) according to standard procedures and photographed using a Nikon 80i microscope (Melville, NY, USA) equipped with a digital camera. Images from three nonconsecutive whole gland cross sections were obtained for each LG. The area of the LG occupied by lymphocytic foci was calculated using ImageJ software by a blinded examiner.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using a Student’s t-test or a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test using Prism 5.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Figure 1, Figure S2, and the Table of Contents Graphic were created with biorender.com.

Results

Purification and characterization of 5FA and 5FV.

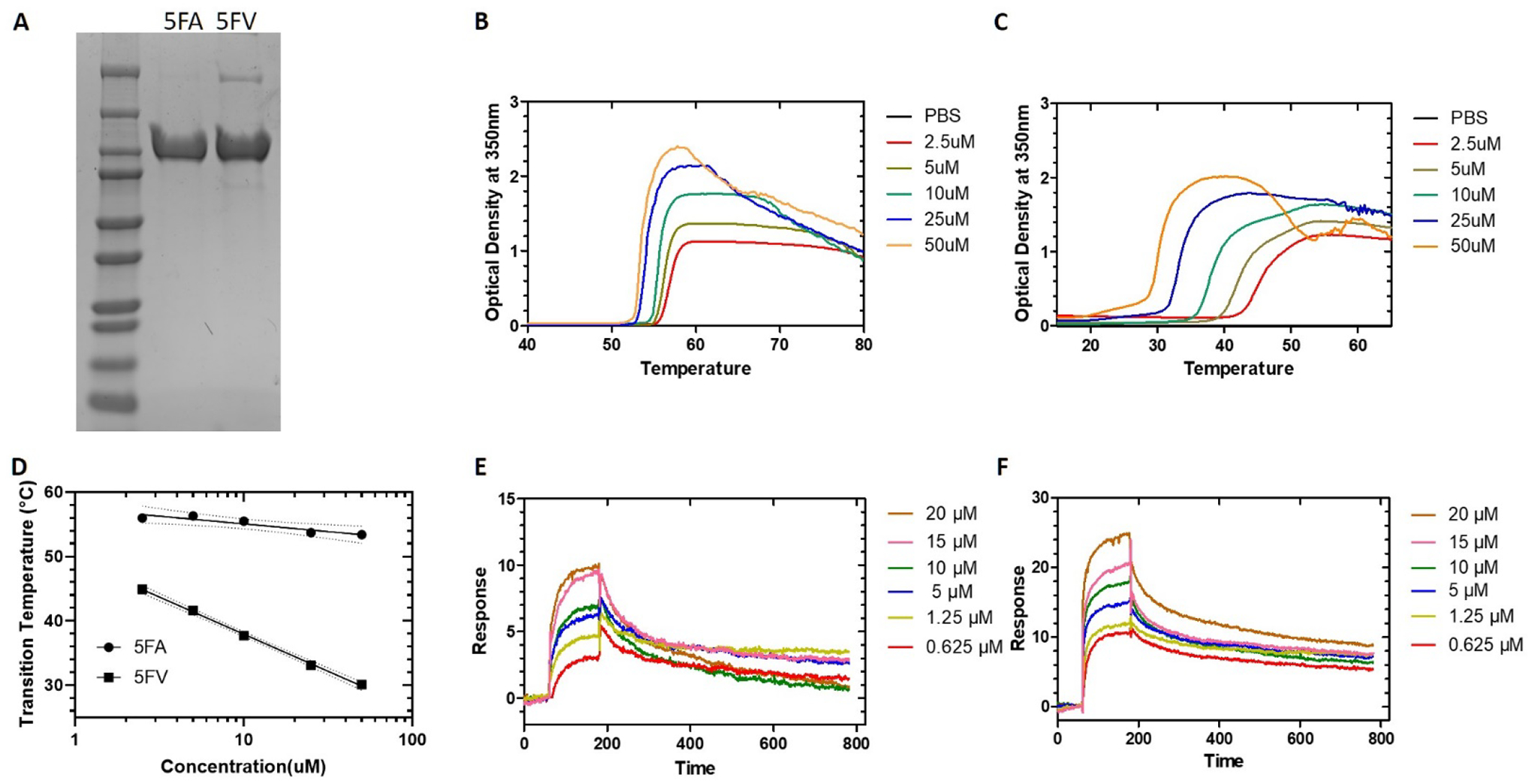

5FA and 5FV were successfully purified from BLR(DE3) competent E. coli via inverse transition cycling with a similar yield of about 80 mg/L. Coomassie blue SDS-PAGE gel analysis showed that both 5FA and 5FV had purity above 90% (Figure 2A). Optical density measurements at 350 nm of purified 5FA and 5FV at a series of different concentrations was used to characterize the temperature-concentration phase diagram for both constructs (Figure 2B, 2C). A biphasic transition, with a small portion undergoing a phase transition at a lower temperature (about 20°C), which was more evident at higher concentrations (50 μM), was seen for 5FV. It is possible that some nucleation event is happening; such a phenomenon was also seen for FAF in our previous publications18.Transition temperature (Tt) follows an inverse relationship with logarithm of the ELP concentration (Figure 2D). Using the fit parameters (Table 1) for 5FA and 5FV, the estimated Tt for 5FA at 300 μM and 400 μM was 51.5°C and 51.2°C, respectively, whereas the estimated Tt for 5FV at the same concentrations was 21.0 °C and 19.6°C. By extrapolation to the estimated concentration used for the in vivo studies, which is between 300 μM and 400 μM, we anticipated that 5FV will form a coacervate whereas 5FA will remain soluble. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was also conducted to study the binding properties between Rapa and 5FA (Figure 2E) or 5FV (Figure 2F). The association (Ka), dissociation (Kd) and equilibrium (KD) constants derived from the sensorgram between Rapa and 5FA or Rapa and 5FV are summarized in Table 1. Both 5FA and 5FV have similar binding affinity for Rapa at 18°C, which is around 60 nM. Notably, this value is significantly higher than the value of other FKBP-ELP constructs we have reported previously at 37°C, which has been about 5 nM19. Since 5FV is not soluble at 37°C, it was not possible to measure the binding properties between 5FV and Rapa at 37°C; therefore, no direct comparison can be made to compare the binding properties with our previously reported constructs at this temperature.

Figure 2. Biophysical characterization of 5FA and 5FV.

A) Coomassie blue staining of purified 5FA and 5FV resolved by SDS-PAGE. B) Optical density at 350 nm of 5FA was monitored as a function of temperature at different concentrations. C) Optical density at 350 nm of 5FV was monitored as a function of temperature at different concentrations. D) Phase transition temperature was plotted vs. concentration as a phase diagram for 5FA and 5FV. The 95% confidence interval around each best-fit line is indicated with dashed lines. E) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensorgram of different concentrations of Rapa monitored on a surface with immobilized 5FA at 18°C. F) SPR sensorgram of indicated concentrations of Rapa monitored on a surface with immobilized 5FV at 18°C.

Table 1.

Phase transition characterization and Rapa binding dynamics of 5FA and 5FV

| Constructs | Temperature-Concentration Phase Diagrama | Ka (M−1s−1) | Kd (s−1) | KD(M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope, m [°C Log(μM)] | Intercept, b [°C] | ||||

| 5FA | 2.4±1.9 | 57.5±2.1 | (2.9±1.0)×104 | (1.5±0.8)×10−3 | (6.3±5.0)×10−8 |

| 5FV | 11.5±0.9 | 49.5±1.1 | (1.7±0.1)×104 | (1.1±1.0)×10−3 | (6.4±0.6)×10−8 |

Phase diagrams for assembly (Fig 2D) were fit with Equation 1. Values represent mean ± SD.

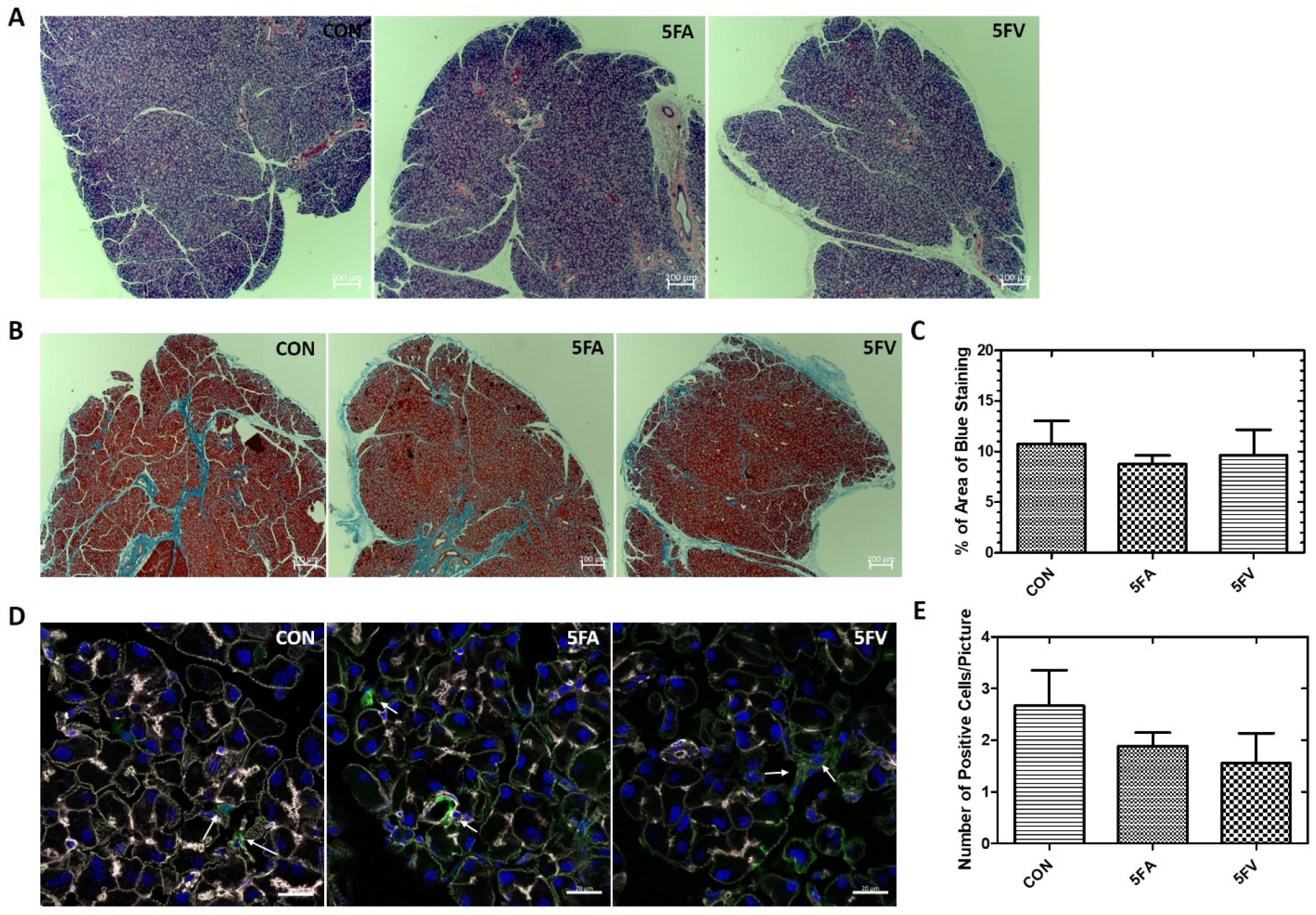

Intra-LG injection does not elicit significant damage to LGs.

A safety evaluation was done to assess the potential damage, such as inflammation or fibrosis, caused by intra-LG injection to the LG. Male C57 mice aged 12–14 weeks old were injected intra-LG with 32 μl of 5FA or 5FV (366 μM) in total, 16 μl per side with 4 injections of 4 μl each. Two weeks after injection, LG from mice were collected for further analysis. H&E staining did not show any significant immune cell infiltration of the LG in 5FA and 5FV treated groups compared with nontreated controls (Figure 3A). Trichrome staining, which visualizes collagen deposition, a marker for fibrosis25, was also conducted to detect any potential fibrosis in the LG (Figure 3B). The ratio of the area of collagen deposition to the area of the whole LG was calculated for all three groups. No significant differences were seen among the three groups, which indicates that intra-LG injection does not cause significant fibrosis in the LG (Figure 3C). Immunofluorescence staining with HSP47 antibody, a marker for active fibroblasts which is elevated in several fibrotic diseases26, was also conducted to further detect fibrosis of LG (Figure 3D). The number of HSP47 positive cells were quantified and compared between the three groups. No significant differences were seen among the three groups, confirming that intra-LG injection does not cause significant fibrosis in the LG (Figure 3E). Based on the above results, we concluded that intra-LG injection is a safe procedure and does not cause significant or long term damage to the glands.

Figure 3. Intra-LG injection does not promote tissue damage or fibrosis.

Male C57 mice were either used as controls (CON) or administered with 32 μl of 5FA or 5FV (366 μM) in total, 16 μl per side with 4 injections of 4 μl each. LG were obtained after 2 weeks. A) H&E staining of a representative LG section from each group (n=3 LGs from 3 different mice in each group, 2 sections per mouse). Scale bar: 200 μm. B) Trichrome staining of a representative LG from each group). Scale bar: 200 μm. C) Quantification of the percentage of the area stained blue with Trichrome. (n=3 LGs from 3 different mice in each group, 2 sections per LG) D) HSP47 immunofluorescence staining of LG representative of each group. White: F-actin, Blue: DAPI, Green: HSP47. Scale bar: 20 μm. E) Quantification of the number of HSP47+ cells in each picture (n=3 LGs from 3 different mice each group, 3 pictures from each LG). Data is presented as mean ± SD.

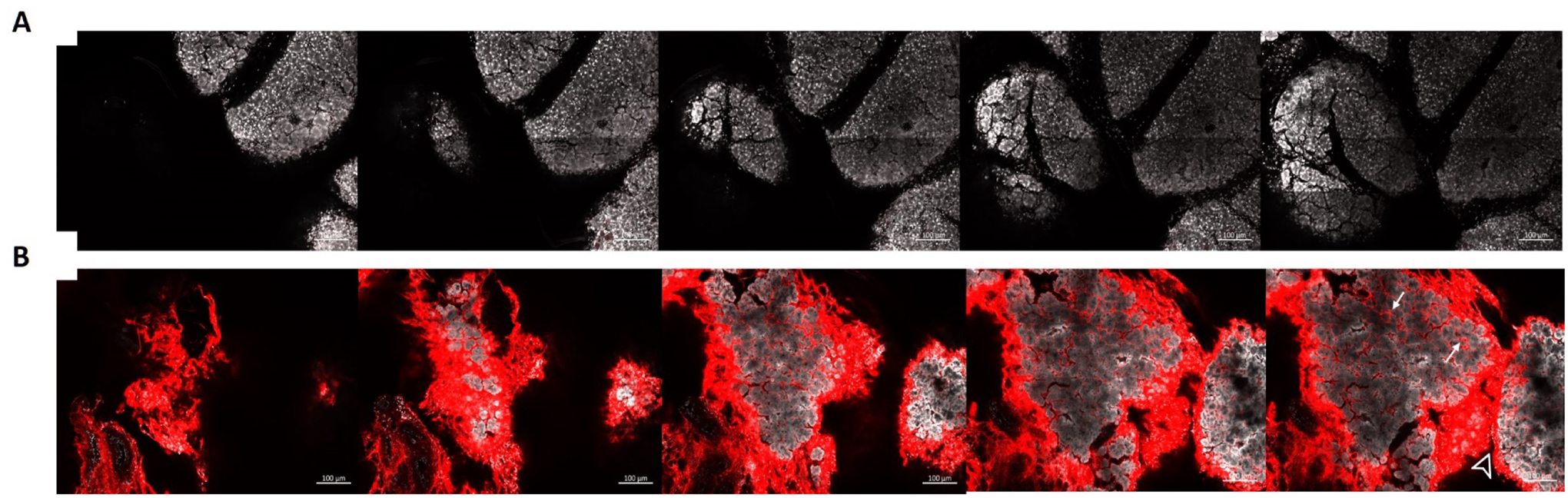

5FV-Rapa forms a depot in the LG after intra-LG injection.

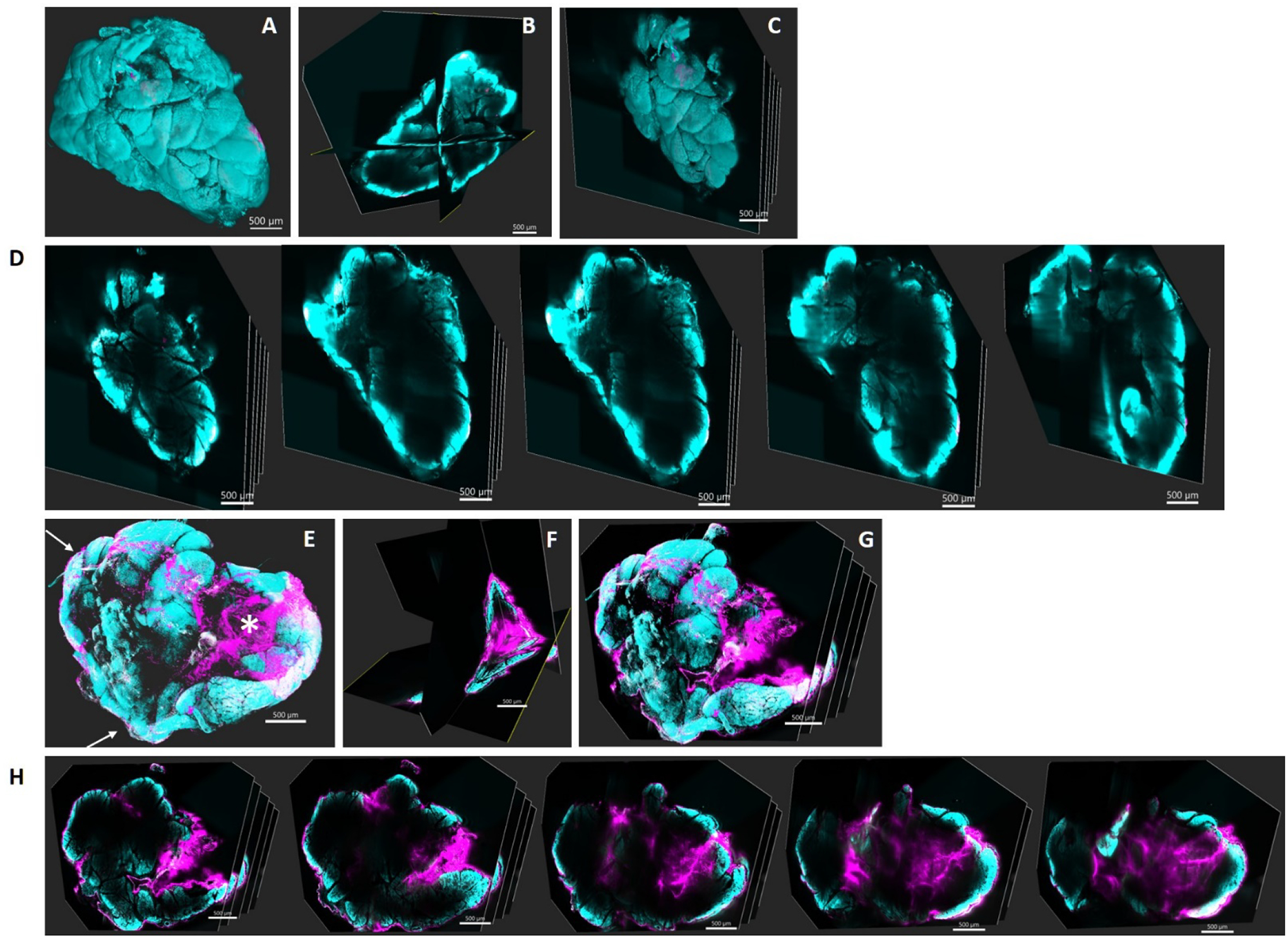

To confirm that 5FV-Rapa does form a depot at the injection site, lightsheet imaging evaluation of the cleared whole LG was done one day after intra-LG injection of Rhodamine labeled ELP-Rapa (Figure 4). No significant depot formation was detected in the LG injected with Rhodamine labeled 5FA-Rapa (Figure 4A,B,C,D,). In sharp contrast, a major depot formed in the 5FV-Rapa treated gland (Figure 4E,F,G,H,), as shown by the asterisk in Figure 4E. Rhodamine signals were also detected in the peripheral area of the LG as shown by the arrows in Figure 4E, suggesting that some 5FV-Rapa was trapped beneath the LG capsule.

Figure 4. Lightsheet imaging of Rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa following intra-LG administration reveals formation of a depot.

Male C57 mice were administered with a single 5 μl injection of rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa or rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa (366 μM of ELP) and LG were collected 1 day after injection. A) A reconstructed 3D image of LG injected with rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa. B) A cross-section of the 3D image in panel A showing three orthogonal planes. C) Serial sections of LG injected with rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa. D) Images of each cross section in panel C. E) A reconstructed 3D image of LG injected with intra-LG rhodamine-5FV-Rapa. F) A cross-section of the 3D image in panel F showing three orthogonal planes at the site of injection. G) Serial sections of LG injected with rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa. H) Images of each cross section in panel G. Magenta: Rhodamine-ELP, Cyan: nuclear stain, Scale bar: 500 μm. Asterisk: depot formed after intra-LG delivery of 5FV-Rapa. Arrows: 5FV-Rapa trapped beneath the capsule after intra-LG injection.

The cleared LG was also imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy in order to evaluate the localization of the ELP-Rapa inside the LG. No significant signal for 5FA-Rapa was detected by confocal microscopy (Figure 5A,). However, a strong signal from the interlobular area as well as the interstitial area between the acini was detected in the LG injected with Rhodamine labeled 5FV-Rapa (Figure 5B,). No significant signal was detected inside the LG acinar cells. Based on these data, we concluded that 5FV-Rapa forms a depot in the LG, primarily in the interlobular area, after intra-LG injection, whereas the soluble control 5FA-Rapa does not form a depot.

Figure 5. Confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging of Rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa injected intra-LG reveals a depot formation.

Male C57 mice were injected with a single intra-LG injection of 5 μl containing rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa or rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa (366 μM of ELP). LG were collected after 1 day. Serial sections were acquired in the cleared tissue at 15 μm intervals following following A) intra-LG injection with Rhodamine-labeled 5FA-Rapa and B) intra-LG injection with Rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa. 5FV-Rapa is retained throughout the LG, especially in the interlobular (arrowhead) and interacinar (arrows) areas after 24 hrs. Red: Rhodamine-ELP, White: nuclear stain, Scale bar: 100 μm.

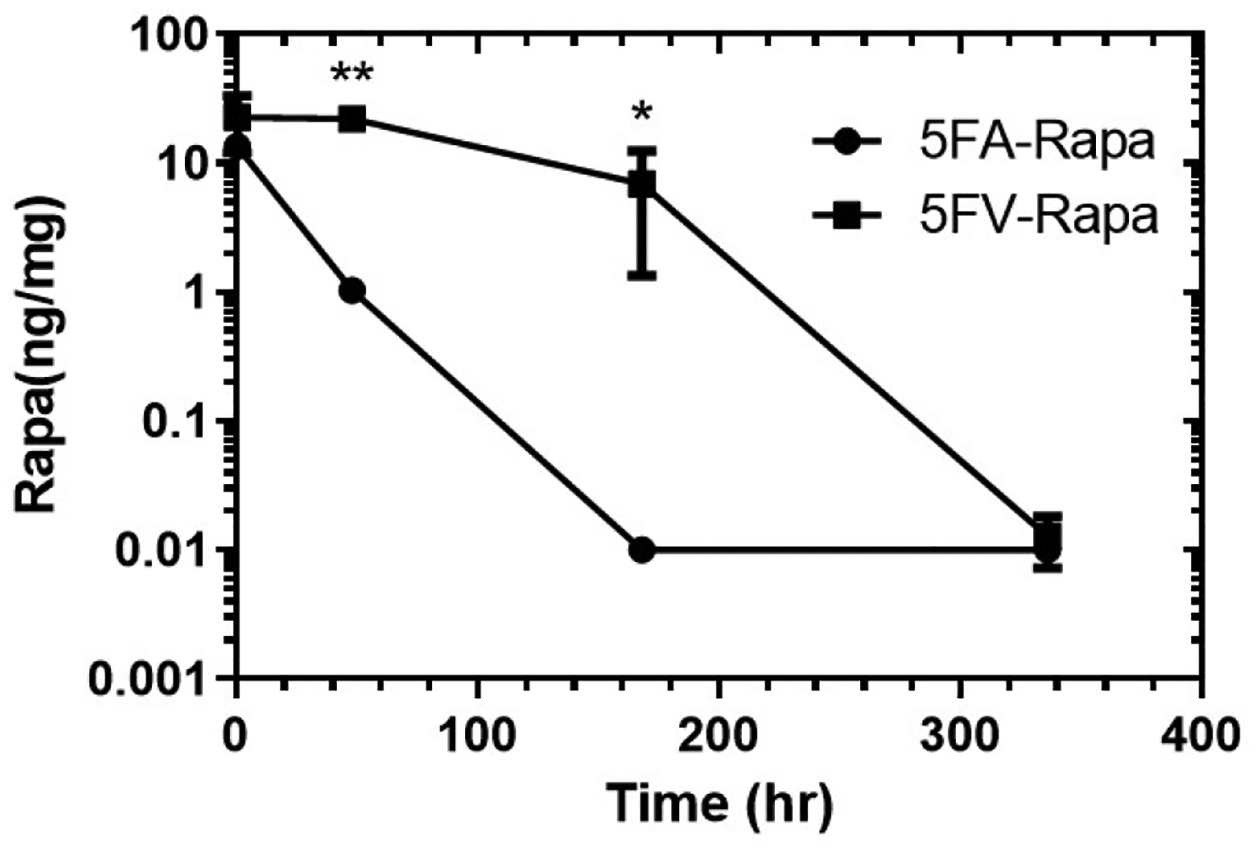

5FV-Rapa exhibits longer retention time in the LG than 5FA-Rapa.

A pharmacokinetics study was conducted to evaluate the retention time of Rapa following intra-LG administration associated with either formulation. Both male and female C57 mice aged 12–14 weeks old were used for the PK study so that any sex differences in terms of elimination rate could be studied. Mice were injected intra-LG with 5FA-Rapa or 5FV-Rapa on both sides of the LG as described in Methods, and LGs were collected after different time point for evaluation of Rapa concentration. The amount of Rapa retained in the LG following intra-LG injection of 5FA-Rapa and 5FV-Rapa was assessed by LC-MS. There was a significantly higher amount of Rapa retained in the LG in the 5FV-Rapa injected group relative to the 5FA-Rapa injected group at 2 days and 7 days post injection, which demonstrates that when delivered by the depot forming 5FV, Rapa is retained in the LG for a much longer period than when delivered by the soluble 5FA (Figure 6). Fourteen days after injection, no detectable amounts of Rapa were seen in either 5FA-Rapa or 5FV-Rapa groups. The MRT of Rapa estimated by Equation 2 for 5FA-Rapa and 5FV-Rapa was 11.7 hr and 75.6 hr, respectively. No sex differences were seen in Rapa levels, implying that the pharmacokinetics following intra-LG injection was similar between males and females. Taken together, intra-LG 5FV-Rapa injection sustains drug levels for around one week making it superior to 5FA-Rapa which releases all the drug in less than a week.

Figure 6. The 5FV-Rapa depot is retained in the LG for significantly longer than its soluble control formulation (5FA-Rapa).

Male and female C57 mice aged 12–14 weeks old are injected with 32 μl of 5FA or 5FV (1.2 mM Rapa, 366 μM ELP) in total, 16 μl per side with 4 injections of 4 μl each in the LGs. Amount of Rapa in the LG at 30 min, 2 days, 7 days and 14 days after intra-LG injection of 5FA-Rapa or 5FV-Rapa is assessed by LC-MS (n=4 mice per group). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

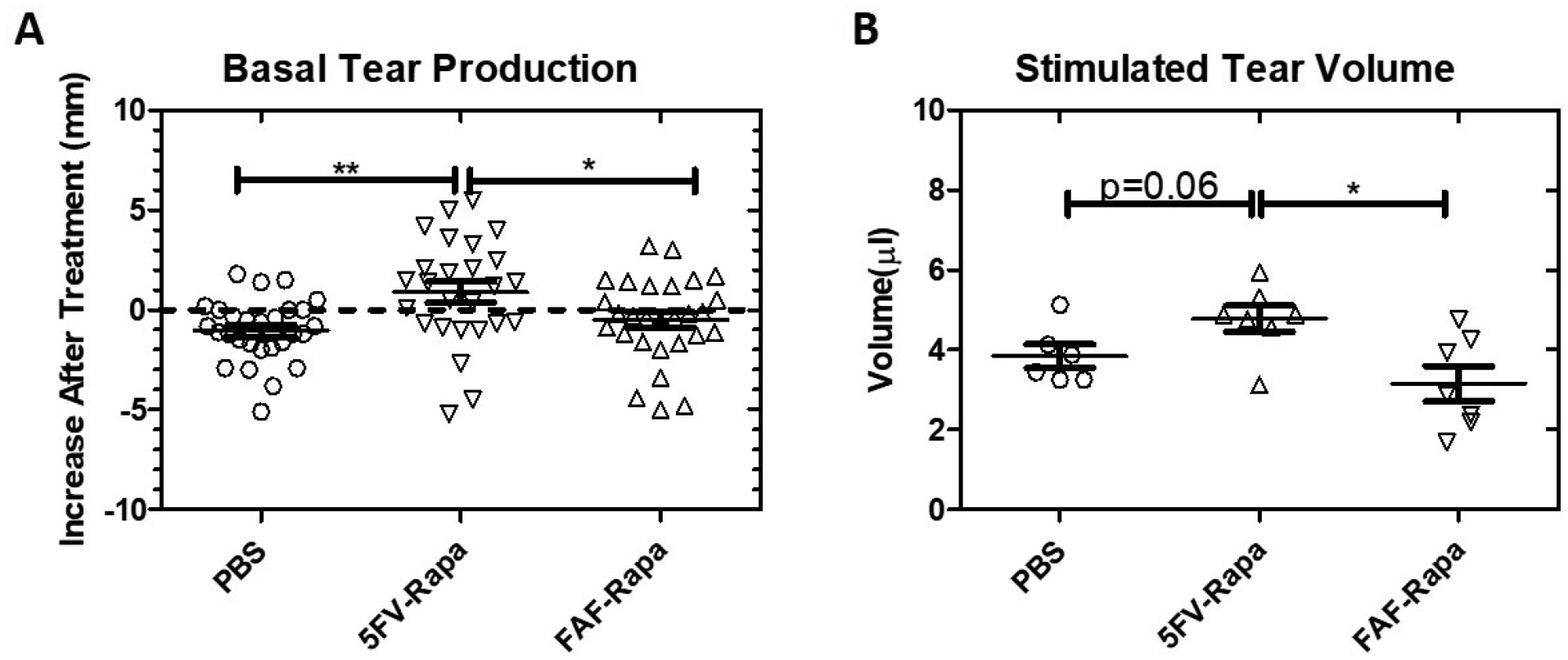

5FV-Rapa increases basal tear secretion and stimulated tear volume.

Since we already confirmed that 5FV is able to retain Rapa in the LG for a significantly longer period of time than 5FA, potentially prolonging its therapeutic effects, we decided to move forward with 5FV as the candidate that would potentially show the highest efficacy by intraLG injection, and to compare it with an already-established treatment, FAF-Rapa18. The dosing regimen for 5FV-Rapa was 0.44 mg/kg given at study onset (total 0.22 mg/kg administered to each side of the LG in 3 different injections of 1 μl), whereas FAF-Rapa was given subcutaneously at 1 mg/kg every other day for 7 doses in total. The surgical cut required for intra-LG injection was clean after surgery and 5FV injection, and was completely healed without complications after 2 weeks (Figure S3). 5FV-Rapa showed significant improvement in basal tear production relative to either intra-LG PBS (0.9±2.7 mm vs −1.0±1.6 mm, p<0.01) or subcutaneous FAF-Rapa (0.9±2.7 mm vs −0.5±2.1 mm), shown as the difference between post-treatment and pre-treatment tear production (Figure 7A). Noticeably, the 5FV-Rapa group was the only group that showed an increased tear production after treatment whereas both PBS and FAF-Rapa showed reduced basal tear production after treatment as disease progresses when mice age. This suggested that 5FV-Rapa may prevent and/or reverse autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Topical carbachol stimulation of the LG reflects the physiological process of muscarinic stimulation of the LG by innervating nerves in response to a stimulus and is thus considered a stimulated secretory response by the LG. The 5FV-Rapa group also showed significantly increased carbachol-stimulated tear secretion when comparing with FAF-Rapa group (4.7±0.9 μl vs 3.2±1.2 μl, p<0.05) and a trend to an increase (p=0.06) compared to the PBS group. (Figure 7B). This further confirms that local administration of 5FV-Rapa has stronger effects than subcutaneous FAF-Rapa in increasing tear production in male NOD mice. This is all the more remarkable given that the cumulative dose given with FAF-Rapa was 16 times greater than the single dose given with single intra-LG injection with 5FV.

Figure 7. Intra-LG 5FV-Rapa significantly enhances basal and stimulated tear secretion.

13 week (diseased) male NOD mice were treated with the dose regimen in Figure 1B. Tear production was evaluated 2 weeks after the initial treatments at the conclusion of the protocol. A) The differences in basal tear production as measured by phenol red thread tests for values post-treatment (mm) and pre-treatment (mm) were plotted. Each data point represents one individual eye (n=28 eyes from 14 mice per group). B) After treatments, tear production from both eyes after topical carbachol stimulation of both LG was plotted. Each data point represents one individual mouse (n=7 mice per group). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

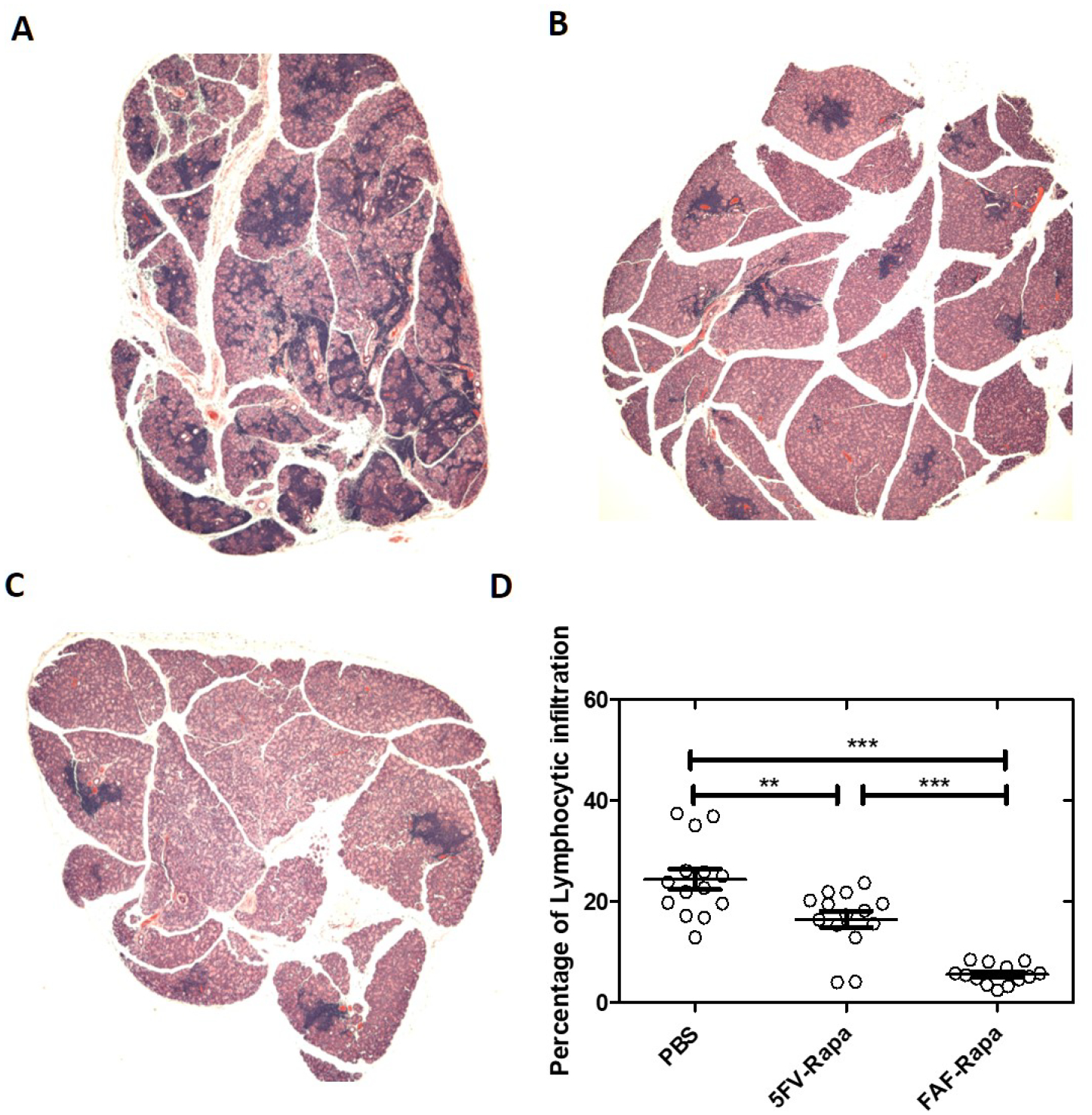

Both 5FV-Rapa and FAF-Rapa reduce LG inflammation in male NOD mice.

Lymphocytic infiltration of the LG quantified as the percentage of the LG area occupied by lymphocytes and determined histologically is a major indicator of disease severity in SS-related dacryoadenitis27. We examined the lymphocytic infiltration of the LG after different treatments using H&E staining. As previously reported18, the subcutaneous FAF-Rapa regimen (5.6%±2.0 vs 24.3%±7.6%, p<0.001) was able to significantly decrease lymphocytic infiltration of the LG compared with PBS. However, a single intra-LG injection of 5FV-Rapa (16.5%±6.5% vs 24.3%±7.6%, p<0.01) also suppressed lymphocytic infiltration (Figure 8). Further flow cytometry studies were done to evaluate the composition of lymphocytes remaining the LG under each conditions, revealing no difference in percentage of infiltrating CD3+ cells, CD3+CD4+ cells, CD3+CD8+ cells, CD45R+ cells, and CD11b+ cells between the three treatments (Figure S4) and suggesting that these infiltrating lymphocytes are decreased proportionally after treatment.

Figure 8. Both 5FV-Rapa and FAF-Rapa reduced lymphocytic infiltration.

Representative H&E staining of NOD mouse LG after treatment as in Figure 1 with A) a single treatment with intra-LG PBS; B) a single treatment of intra-LG 5FV-Rapa (0.44 mg/kg with 0.22mg/kg to each gland.) C) subcutaneous FAF-Rapa injections (1mg/kg × 7doses). D) Quantification of the percentage of area of LG covered by lymphocytes after different treatments (n=14 LG from 14 different mice per group). **p<0.01***p<0.001.

5FV-Rapa exhibits significantly less systemic toxicity than FAF-Rapa.

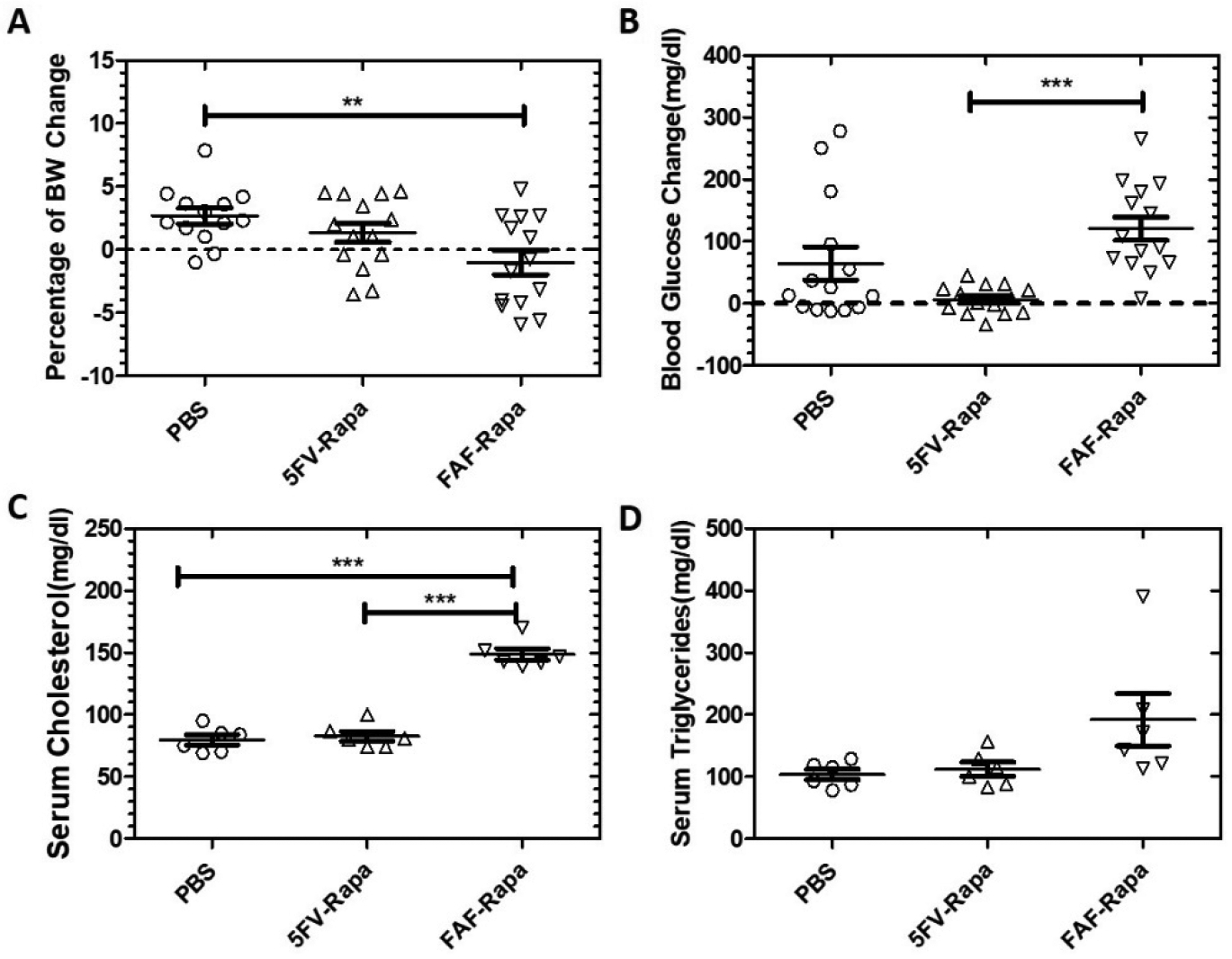

It is well documented that Rapa treatment can cause onset of hyperglycemia or exacerbate pre-existing insulin resistance, as well as disrupt normal lipid metabolism in both human and experimental animals28–31. As previously reported, 20%–30%of male NOD mice spontaneously develop type I diabetes as a result of lymphocytic infiltration of pancreas by 5 months32, 33. Here and in previous work, we have used male NOD mice younger than 5 months, when most mice are diabetes free, in studies of SS disease biology as well as in development of potential SS therapeutics10, 18. However, their predisposition to hyperglycemia represents a good model with which to test the effects of Rapa across different treatment groups. The FAF-Rapa group showed significant body weight reduction when compared with the intra-LG PBS group (−1.0±3.6% vs +2.7±2.3%, p<0.01), whereas no significant difference was observed between 5FV-Rapa and PBS (+1.4±2.9% vs +2.7±2.3%)(Figure 9A). Blood glucose in mice was also assessed before and after treatment regimens. The FAF-Rapa group showed significantly increased blood glucose compared with 5FV-Rapa (+120.9±71.5 mg/dl vs +6.2±23.0 mg/dl, p<0.001)(Figure 9B). A few mice in the PBS group showed increased blood glucose levels, possibly due to early development of type I diabetes34. While onset is typically 5–6 months in the males, individual variability occurs and, in a large cohort, some mice will show evidence of earlier onset. Serum cholesterol levels after treatment were also significantly increased in the FAF-Rapa group when compared with both intra-LG PBS and 5FV-Rapa, respectively (148.8±11.3 mg/dl vs 79.7±10.1 mg/dl, p<0.001; 148.8±11.3 mg/dl vs 82.7±9.8 mg/dl, p<0.001), whereas no significant difference was seen between 5FV-Rapa and intra-LG PBS(Figure 9C). There was also a trend to increased serum triglycerides post-treatment in the FAF-Rapa group when compared with PBS and 5FV-Rapa (Figure 9D).

Figure 9. 5FV-Rapa has significantly less systemic toxicity than FAF-Rapa.

Body weight and serum chemistry were evaluated 2 weeks after the initial injections in 13 week male NOD mice at study endpoint as shown in Figure 1. A) Percentage of body weight (BW) change post-treatment compared with pre-treatment (n=14). B) Change in blood glucose post-treatment compared with pre-treatment(n=14). C) Serum cholesterol level after different treatments (n=6). D) Serum triglycerides levels after different treatments (n=6). **p<0.01***p<0.001.

Discussion

ELPs are thermo-responsive biopolymers consisting of pentameric repeats of (Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly)n that can undergo reversible inverse phase transition wherein they remain soluble below their transition temperature (Tt) and form insoluble coacervates above Tt. The Tt is tunable by the number of pentameric repeats and the biophysical properties of the Xaa. As the number of repeats or hydrophobicity of Xaa increases, Tt decreases as a result. Thus it is possible to engineer an ELP with any desired Tt by adjusting the number of repeats and choosing different Xaa. Here, by choosing a hydrophobic Xaa, Valine, we successfully engineered an ELP with Tt below physiological temperature, which instantly formed an insoluble coacervate upon injection. The use of Valine as Xaa to create an ELP with low Tt has been reported previously as a strategy to deliver a sustained released depot into mice35. Another soluble control, 5FA, was also developed where a less hydrophobic amino acid, Alanine, was selected as Xaa for comparison with 5FV. With the lightsheet imaging system and 3D reconstruction process, we were able to visualize and confirm that 5FV forms a depot inside the LG, whereas 5FA does not form a comparable depot in the LG. As a consequence, 5FV-Rapa showed significantly longer retention time and was able to maintain Rapa in LG for longer time after intra-LG injection compared with 5FA, which suggests a promising future for using ELPs with low transition temperature for local sustained release.

Mouse LG are small organs normally weighing 20–40 mg per pair, which limits the volume that can be injected. The practical volume for intra-LG injection reported by previous studies ranges from 2 μl to 50 μl35–37. In order to deliver sufficient Rapa dosage through direct intra-LG injection, we developed a high-capacity carrier for Rapa which could carry a large amount of Rapa per carrier molecule. Compared with the Rapa carriers we developed previously such as FSI17 or FAF19 which can only carry 1 or 2 Rapa per carrier molecule, the high capacity carrier 5FV can carry 5 Rapa per carrier molecule, greatly increasing the dosage of Rapa that can be administered into LG with a limited injection volume.

We have previously evaluated ELP degradation in vitro in response to diverse proteases, although FKBP fusions were not evaluated. ELPs were degraded by collagenase and elastase38. Some preliminary in vitro and in vivo experiments were conducted to investigate the release mechanism of Rapa. Rhodamine-labeled 5FV-Rapa, with or without elastase was dialyzed (10 kDa cut-off) under sink conditions against PBS at 37°C. The mixture from the dialysis cassette was collected at intervals and analyzed by SDS-PAGE to assess ELP degradation and by high-performance liquid chromatography in parallel to measure Rapa concentration. No significant protein degradation was seen in 5FV-Rapa without elastase; conversely, no 5FV was detected in the group with elastase even after only 2 hrs. Peptide degradation products between 10–20 kDa, were detected in the group with elastase (Figure S5A). Rapa concentration was also measured at 2h, 24h, and 48h after dialysis to assess the drug release. No significant drug loss was detectable in either group (Figure S5B). We propose that elastase is only able to degrade the ELP component of 5FV, but not the FKBP component. Therefore Rapa remains associated with FKBP and is retained in the dialysis cassette.

We also assessed the ELP carrier degradation in vivo. NOD mice were treated with Rhodamine-labeled FAF-Rapa subcutaneously, 5FA-Rapa given intraLG, and 5FV-Rapa given intraLG, comparably to the efficacy study. LG were collected 24 hr after treatment and lysates prepared for SDS-PAGE. No significant Rhodamine signal was seen in the FAF-Rapa and 5FA-Rapa groups; however, a significant amount of 5FV was detected in LG lysates. Protein bands of lower molecular weight were also detected in the 5FV group, suggestive of degradation of 5FV in the LG (Figure S5C, white arrows). Moreover, this finding validates the rapid loss of 5FA signal relative to 5FV signal in the LG seen by light sheet and confocal fluorescence imaging in Fig.4 and Fig 5.

We have previously reported that ELPs can be degraded by collagenase and elastase38. It is possible that ELP-FKBP fusions are fully degraded by various proteases in the LG such as matrix metalloproteinases and cathepsins, thus releasing Rapa. Another possible mechanism is that ELP linkers are degraded by collagenase and elastase in the LG, while Rapa remains associated with FKBP. The FKBP-Rapa complex could be internalized into the cells followed by further degradation in the lysosomes by lysosomal enzymes. It is also possible that 5FV-Rapa monomer is gradually released from the depot, then internalized into the cells. It is very likely that multiple release mechanisms as mentioned above occur simultaneously so further studies are needed to investigate the role of each mechanism.

The measures of basal and stimulated tear secretion are both important for prevention and therapy of autoimmune-mediated dry eye. Basal tear production mainly reflects constitutive tear protein and fluid release by the lacrimal gland that occurs in the absence of acute ocular surface stimulation, providing a consistent low level of tears39, 40. Stimulated tear production, mimicked in our model by topical stimulation of the lacrimal gland with the muscarinic agonist, carbachol, reflects the response of the lacrimal gland to acute neural stimulation due to ocular surface irritation, and which increases tear flow through increased mobilization of the fusion of secretory vesicles40–42. Since the ocular surface exhibits increased irritation due to dryness, the consequent hyperstimulation of ocular surface nerves in dry eye may result in desensitization of both responses43, a phenomenon known as functional quiescence. Significantly increased basal tearing, seen in the 5FV-Rapa group relative to both other groups, reflects the increased production of the constitutively produced tear film which would result in a more consistently lubricated ocular surface. The finding that there is a significant increase in stimulated tear flow between the 5FV-Rapa group compared to FAF-Rapa and also a trend to an increased stimulated tear flow (p=0.06) in the 5FV-Rapa group compared with the PBS group further suggests some improvement in the stimulated response, which reflects the increased ability to generate tears in response to irritation of the ocular surface.

Systemic administration of FAF-Rapa appeared to elicit a more robust inhibition of lymphocytic infiltration of the NOD mice LG when compared with intra-LG delivery of 5FV-Rapa (Figure 8D). This may be due to the notable difference in Rapa dose in between the Rapa treatment regimens. In the FAF-Rapa group, the NOD mice received 7 doses of 1 mg/kg of Rapa while in the 5FV group, the NOD mice received only one dose of 0.44mg/kg of Rapa in 5FV-Rapa group due to the limited volume which could be administered to the LG. While the significantly higher dose of FAF-Rapa group may contribute to its stronger inhibition of LG lymphocytic infiltration; other mechanisms can also play a role. Systemic FAF-Rapa could possibly lead to universal immunosuppression as well as decreased circulating lymphocytes, thus enabling fewer available to migrate into LG, whereas intra-LG 5FV-Rapa might not have had a comparable effect due to limited access to the systemic circulation. Within this context, it is notable that intra-LG 5FV but not systemic FAF was able to improve both basal and stimulated tear production (Figure 7) suggesting that local effects may be more important in eliciting a practical improvement in aqueous tear production. Further evaluation of blood and spleen lymphocyte counts as well as additional evaluation of the precise relationship between lymphocytic infiltration and loss of tear production is required to resolve these issues.

It is well-documented that prolonged systemic Rapa treatment can impair the function of pancreatic β-cells and cause glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia44–46. Metabolic syndrome is a known risk factor for dry eye diseases due to abnormal tear dynamics, tear film dysfunction, and altered LG function47, 48, which may explain the lack of improvement in tear production in the FAF-Rapa treatment group since systemic Rapa administration elicits significant metabolic dysfunction. In contrast, intra-LG delivery of Rapa by 5FV leads to significant lower systemic exposure to Rapa (Figure S6), thus significantly reducing the systemic toxicity of Rapa, which may contribute to its ability to significantly improve tear production relative to FAF-Rapa.

Our group has previously developed a diblock copolymer ELP carrier for Rapa called FSI which significantly inhibited LG inflammation and improved the LG secretory function in male NOD mice when given intravenously.17 However, although systemic toxicity to kidneys was evaluated for this delivery modality, which was improved with FSI-Rapa versus free Rapa, glucose elevations were not evaluated in this study. It was also deemed desirable to have an alternative to intravenous delivery of the Rapa formulation. We therefore developed a second-generation bi-headed Rapa carrier named FAF which could inhibit LG inflammation comparably to FSI-Rapa when given subcutaneously. However, subcutaneous administration of FAF-Rapa causes severe hyperglycemia in NOD mice which is a well-documented side effects of Rapa18, and was first evaluated in this study. Since one would expect repeat dosing of FSI-Rapa to elicit similar adverse effects on blood glucose if given subcutaneously, it was not compared side by side. Instead we developed a local, sustained delivery method for Rapa. The logic of local delivery is that it would treat the LG inflammation without introducing as much drug into the systemic circulation, thus avoiding the systemic toxicity of repeated, systemic Rapa. That goal has been accomplished here, through the 5FV depot-forming formulation of Rapa that inhibits local inflammation without causing significant systemic toxicity, which moves the ELP-Rapa delivery strategy closer to clinical application. Thus, these three agents represent a gradual evolution in optimizing therapies for local delivery of Rapa directly to the site of inflammation, with each successive platform improving on limitations of the previous iteration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a sustained local delivery method for Rapa, taking advantage of the thermal responsive property of ELPs. Intra-LG delivery is safe and does not cause severe inflammation or fibrosis of the LG. When delivered by 5FV, Rapa inhibit local inflammation and improves tear production without causing any systemic side effects, which provides a new future potential therapy for SS-related dacryoadenitis. This method of depot-based delivery of Rapa may be suitable for local delivery to sites of inflammation in other autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the M-Squared team: Tom Mitchell, Pedro Almada, Naveen Hosni, and Valentina Loschiavo for all their time and effort troubleshooting, working out calibration standards, and continuous software updates. We also thank the USC Translational Imaging Center Advanced Light Microscopy Core, the USC Office of the Provost, and Scott Fraser, Ph. D., for supporting the imaging efforts. Finally, we thank the Center of Excellence in NanoBiophysics at the University of Southern California and the USC School of Pharmacy Translational Research Laboratory for their assistance.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NIH grants R01EY026635 to SHA and JAM, NIH R01GM114839 to JAM, NIH R01EY011386 to SHA, P30 EY029220 (Center Core Grant for Vision Research) and an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. Additional project support was from P30CA014089 (USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center), and P30DK048522 (Liver Histology Core of the USC Research Center for Liver Diseases)

Abbreviations:

- AUC

area under the curve

- AUMC

area under the moment curve

- ELPs

Elastin-Like Polypeptides

- FKBP

FK-506 binding protein 12

- Rh

hydrodynamic radius

- LG

lacrimal gland

- mPET

modified pET25b (+) vector

- MRT

mean residence time

- NOD

Non-obese Diabetic

- pSS

primary Sjögren’s syndrome

- Rapa

Rapamycin

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- SG

salivary glands

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- sSS

secondary Sjögren’s syndrome

- SS

Sjögren’s syndrome

- Tt

transition temperature

- 3DISCO

3-dimensional imaging of solvent cleared organs

Footnotes

Supporting Information:

Fig S1. Cloning schematic of 5FA and 5FV.

Fig S2. Schematic illustration of the process of intra-LG gland injection and therapeutic study design.

Fig S3. Evaluation of the surgical cut after intra-LG injection.

Fig S4. Flow cytometry analysis of lymphocyte composition in the LG after treatments.

Figure S5. In Vitro and In Vivo degradation of ELP-FKBP.

Figure S6. Amount of Rapa in the blood 24 h after treatment.

Supplemental Methods for flow cytometry

References:

- 1.Lemp MA, Dry eye (Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca), rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjogren’s syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol 2005, 140, (5), 898–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen CQ; Peck AB, Unraveling the pathophysiology of Sjogren syndrome-associated dry eye disease. Ocul. Surf 2009, 7, (1), 11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nocturne G; Mariette X, Sjogren Syndrome-associated lymphomas: an update on pathogenesis and management. Br. J. Haematol 2015, 168, (3), 317–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin B; Wang J; Yang Z; Yang M; Ma N; Huang F; Zhong R, Epidemiology of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis 2015, 74, (11), 1983–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foulks GN; Forstot SL; Donshik PC; Forstot JZ; Goldstein MH; Lemp MA; Nelson JD; Nichols KK; Pflugfelder SC; Tanzer JM; Asbell P; Hammitt K; Jacobs DS, Clinical Guidelines for Management of Dry Eye Associated with Sjögren Disease. Ocul. Surf 2015, 13, (2), 118–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ames P; Galor A, Cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsions for the treatment of dry eye: a review of the clinical evidence. Clin Investig (Lond) 2015, 5, (3), 267–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland EJ; Luchs J; Karpecki PM; Nichols KK; Jackson MA; Sall K; Tauber J; Roy M; Raychaudhuri A; Shojaei A, Lifitegrast for the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: Results of a Phase III, Randomized, Double-Masked, Placebo-Controlled Trial (OPUS-3). Ophthalmology 2017, 124, (1), 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheppard JD; Torkildsen GL; Lonsdale JD; D’Ambrosio FA Jr.; McLaurin EB; Eiferman RA; Kennedy KS; Semba CP, Lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5.0% for treatment of dry eye disease: results of the OPUS-1 phase 3 study. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, (2), 475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tauber J; Karpecki P; Latkany R; Luchs J; Martel J; Sall K; Raychaudhuri A; Smith V; Semba CP, Lifitegrast Ophthalmic Solution 5.0% versus Placebo for Treatment of Dry Eye Disease: Results of the Randomized Phase III OPUS-2 Study. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, (12), 2423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah M; Edman MC; Reddy Janga S; Yarber F; Meng Z; Klinngam W; Bushman J; Ma T; Liu S; Louie S; Mehta A; Ding C; MacKay JA; Hamm-Alvarez SF, Rapamycin Eye Drops Suppress Lacrimal Gland Inflammation In a Murine Model of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci 2017, 58, (1), 372–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer DE; Chilkoti A, Genetically encoded synthesis of protein-based polymers with precisely specified molecular weight and sequence by recursive directional ligation: examples from the elastin-like polypeptide system. Biomacromolecules. 2002, 3, (2), 357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Despanie J; Dhandhukia JP; Hamm-Alvarez SF; MacKay JA, Elastin-like polypeptides: Therapeutic applications for an emerging class of nanomedicines. J. Controlled Release 2016, 240, 93–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeboah A; Cohen RI; Rabolli C; Yarmush ML; Berthiaume F, Elastin-like polypeptides: A strategic fusion partner for biologics. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2016, 113, (8), 1617–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciofani G; Genchi GG; Mattoli V; Mazzolai B; Bandiera A, The potential of recombinant human elastin-like polypeptides for drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2014, 11, (10), 1507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacEwan SR; Chilkoti A, Applications of elastin-like polypeptides in drug delivery. J. Controlled Release 2014, 190, 314–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Despanie J; Dhandhukia JP; Hamm-Alvarez SF; MacKay JA, Elastin-like polypeptides: Therapeutic applications for an emerging class of nanomedicines. J. Controlled Release 2016, 240, 93–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah M; Edman MC; Janga SR; Shi P; Dhandhukia J; Liu S; Louie SG; Rodgers K; Mackay JA; Hamm-Alvarez SF, A rapamycin-binding protein polymer nanoparticle shows potent therapeutic activity in suppressing autoimmune dacryoadenitis in a mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome. J. Controlled Release 2013, 171, (3), 269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee C; Guo H; Klinngam W; Janga SR; Yarber F; Peddi S; Edman MC; Tiwari N; Liu S; Louie SG; Hamm-Alvarez SF; MacKay JA, Berunda Polypeptides: Biheaded Rapamycin Carriers for Subcutaneous Treatment of Autoimmune Dry Eye Disease. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2019, 16, (7), 3024–3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhandhukia JP; Li Z; Peddi S; Kakan S; Mehta A; Tyrpak D; Despanie J; MacKay JA, Berunda Polypeptides: Multi-Headed Fusion Proteins Promote Subcutaneous Administration of Rapamycin to Breast Cancer In Vivo. Theranostics. 2017, 7, (16), 3856–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhandhukia JP; Shi P; Peddi S; Li Z; Aluri S; Ju Y; Brill D; Wang W; Janib SM; Lin Y-A; Liu S; Cui H; MacKay JA, Bifunctional Elastin-like Polypeptide Nanoparticles Bind Rapamycin and Integrins and Suppress Tumor Growth in Vivo. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, (11), 2715–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ju Y; Guo H; Yarber F; Edman MC; Peddi S; Janga SR; MacKay JA; Hamm-Alvarez SF, Molecular Targeting of Immunosuppressants Using a Bifunctional Elastin-Like Polypeptide. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, (9), 2358–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Research Council. In Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Edition. National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ertürk A; Bradke F, High-resolution imaging of entire organs by 3-dimensional imaging of solvent cleared organs (3DISCO). Exp. Neurol 2013, 242, 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ju Y; Janga SR; Klinngam W; MacKay JA; Hawley D; Zoukhri D; Edman MC; Hamm-Alvarez SF, NOD and NOR mice exhibit comparable development of lacrimal gland secretory dysfunction but NOD mice have more severe autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Exp. Eye Res 2018, 176, 243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J; Lee SK; Abd-Elgaliel WR; Liang L; Galende E-Y; Hajjar RJ; Tung C-H, Assessment of Cardiovascular Fibrosis Using Novel Fluorescent Probes. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, (4), e19097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razzaque MS; Taguchi T, The possible role of colligin/HSP47, a collagen-binding protein, in the pathogenesis of human and experimental fibrotic diseases. Histol. Histopathol 1999, 14, (4), 1199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janga SR; Shah M; Ju Y; Meng Z; Edman MC; Hamm-Alvarez SF, Longitudinal analysis of tear cathepsin S activity levels in male non-obese diabetic mice suggests its potential as an early stage biomarker of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Biomarkers. 2019, 24, (1), 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraenkel M; Ketzinel-Gilad M; Ariav Y; Pappo O; Karaca M; Castel J; Berthault MF; Magnan C; Cerasi E; Kaiser N; Leibowitz G, mTOR inhibition by rapamycin prevents beta-cell adaptation to hyperglycemia and exacerbates the metabolic state in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2008, 57, (4), 945–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamming DW; Ye L; Katajisto P; Goncalves MD; Saitoh M; Stevens DM; Davis JG; Salmon AB; Richardson A; Ahima RS; Guertin DA; Sabatini DM; Baur JA, Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2012, 335, (6076), 1638–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen JL; Bennett RG; Burkman T; Ramirez AL; Yamamoto S; Gulizia J; Radio S; Hamel FG, Tacrolimus and sirolimus cause insulin resistance in normal sprague dawley rats. Transplantation. 2006, 82, (4), 466–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrisett JD; Abdel-Fattah G; Hoogeveen R; Mitchell E; Ballantyne CM; Pownall HJ; Opekun AR; Jaffe JS; Oppermann S; Kahan BD, Effects of sirolimus on plasma lipids, lipoprotein levels, and fatty acid metabolism in renal transplant patients. J. Lipid Res 2002, 43, (8), 1170–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bach JF, Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus as an autoimmune disease. Endocr. Rev 1994, 15, (4), 516–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kikutani H; Makino S, The murine autoimmune diabetes model: NOD and related strains. Adv. Immunol 1992, 51, 285–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atkinson MA; Leiter EH, The NOD mouse model of type 1 diabetes: As good as it gets? Nat. Med 1999, 5, (6), 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W; Jashnani A; Aluri SR; Gustafson JA; Hsueh P-Y; Yarber F; McKown RL; Laurie GW; Hamm-Alvarez SF; MacKay JA, A thermo-responsive protein treatment for dry eyes. J. Controlled Release 2015, 199, 156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin B.-w.; Chen M.-z.; Fan S.-x.; Chuck RS; Zhou S.-y., Effect of 0.025% FK-506 Eyedrops on Botulinum Toxin B–Induced Mouse Dry Eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci 2015, 56, (1), 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zoukhri D; Macari E; Kublin CL, A single injection of interleukin-1 induces reversible aqueous-tear deficiency, lacrimal gland inflammation, and acinar and ductal cell proliferation. Exp. Eye Res 2007, 84, (5), 894–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah M; Hsueh P-Y; Sun G; Chang HY; Janib SM; MacKay JA, Biodegradation of elastin-like polypeptide nanoparticles. Protein Sci. 2012, 21, (6), 743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodges RR; Dartt DA, Regulatory pathways in lacrimal gland epithelium. Int. Rev. Cytol 2003, 231, 129–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willcox MDP; Argüeso P; Georgiev GA; Holopainen JM; Laurie GW; Millar TJ; Papas EB; Rolland JP; Schmidt TA; Stahl U; Suarez T; Subbaraman LN; Uçakhan O; Jones L, TFOS DEWS II Tear Film Report. Ocul. Surf 2017, 15, (3), 366–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodges RR; Dartt DA, Regulatory Pathways in Lacrimal Gland Epithelium. Int. Rev. Cytol 2003, 231, 129–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wullschleger S; Loewith R; Hall MN, TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006, 124, (3), 471–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belmonte C; Nichols JJ; Cox SM; Brock JA; Begley CG; Bereiter DA; Dartt DA; Galor A; Hamrah P; Ivanusic JJ; Jacobs DS; McNamara NA; Rosenblatt MI; Stapleton F; Wolffsohn JS, TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. Ocul. Surf 2017, 15, (3), 404–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fraenkel M; Ketzinel-Gilad M; Ariav Y; Pappo O; Karaca M; Castel J; Berthault M-F; Magnan C; Cerasi E; Kaiser N; Leibowitz G, mTOR Inhibition by Rapamycin Prevents β-Cell Adaptation to Hyperglycemia and Exacerbates the Metabolic State in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2008, 57, (4), 945–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houde VP; Brûlé S; Festuccia WT; Blanchard P-G; Bellmann K; Deshaies Y; Marette A, Chronic Rapamycin Treatment Causes Glucose Intolerance and Hyperlipidemia by Upregulating Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and Impairing Lipid Deposition in Adipose Tissue. Diabetes. 2010, 59, (6), 1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schindler CE; Partap U; Patchen BK; Swoap SJ, Chronic rapamycin treatment causes diabetes in male mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014, 307, (4), R434–R443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moss SE; Klein R; Klein BEK, Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Dry Eye Syndrome. Arch. Ophthalmol 2000, 118, (9), 1264–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X; Zhao L; Deng S; Sun X; Wang N, Dry Eye Syndrome in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Prevalence, Etiology, and Clinical Characteristics. J.Ophthalmol 2016, 2016, 8201053–8201053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.