Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Older adults with diabetes mellitus are susceptible to sarcopenia. Diffusion tensor imaging studies have also shown that patients with diabetes have altered white matter integrity. However, the relationship between these structural changes in white matter and sarcopenia remains poorly understood.

Materials and Methods

The study included 284 older patients (aged ≥65 years) who visited the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital Frailty Clinic. We used diffusion tensor imaging to measure fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) to evaluate changes in white matter integrity. We investigated the associations between sarcopenia, or its diagnostic components, and FA or MD in seven white matter tracts considered to be associated with sarcopenia according to the patients’ diabetes status.

Results

We found significantly low FA or high MD values in the bilateral anterior thalamic radiations (ATR) and right inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus (IFOF) of patients with Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2019‐defined sarcopenia, in all patients and those with diabetes. Using binominal regression analyses, we associated low FA values in the left ATR and right IFOF with sarcopenia in all patients and those with diabetes, after adjusting for age, gender, HbA1c, blood pressure, cognitive function, physical activity, depression, nutritional status, and inflammation.

Conclusions

White matter alterations in left ATR and right IFOF are associated with the prevalence of sarcopenia in patients with diabetes. Specific changes to the left ATR and right IFOF tracts could play critical roles in the occurrence of sarcopenia in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Diffusion tensor imaging, Sarcopenia

Older adults with diabetes mellitus are susceptible to sarcopenia and altered white matter integrity. Using diffusion tensor imaging technique, we found alterations in left anterior thalamic radiation and right inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus are associated with sarcopenia in patients with diabetes.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the number of patients with diabetes mellitus has increased globally. In 2019, an estimated 463 million people suffered from this disease worldwide 1 . Among them, the number of older adults with diabetes is increasing, especially in developed countries. Older patients are susceptible to sarcopenia. Several observational studies have shown that patients with diabetes are at high risk of losing appendicular muscle mass and having low muscle quality 2 , 3 . Furthermore, diabetes patients with sarcopenia have a higher fall and fracture risk than those without sarcopenia 4 . Thus, it is essential to screen for sarcopenia in people with diabetes as early as possible.

Several reports indicate patients with diabetes have altered white matter integrity, as detected by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) on brain MRI scans 5 . DTI can be used to detect early damage to white matter integrity by measuring water molecules’ diffusibility in nerve fibers 6 . There are several advantages to using DTI; the technique is sensitive to subtle white matter alterations that cannot be detected by conventional MRI, and it can be used to evaluate the damage to each white matter tract separately 6 .

Diabetes is associated with high incidences of both sarcopenia and altered white matter integrity. Thus, we hypothesized that structural changes in specific white matter regions could explain sarcopenia susceptibility among people with diabetes. Furthermore, we postulated that altered white matter tracts involved in executive function are associated with sarcopenia. Executive function is a series of processes by which we take appropriate actions efficiently in an organized way; thus, the impairment of this cognitive domain leads to decreased physical performance. This domain is impaired in the early stages of cognitive dysfunction in diabetes patients 7 . Previous reports have shown that the anterior thalamic radiations (ATR) and superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) 8 , which include nerve fibers that connect the anterior lobes and other regions, and the corpus callosum, which connects the cerebral hemispheres 9 , are involved in executive function. Furthermore, we theorized that changes to the tracts involved in visuospatial activity are also associated with sarcopenia, because the deterioration of visuospatial function affects muscle strength and physical performance. The inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus (IFOF) is involved in visuospatial activity 10 .

Thus, in the present study, we investigated the association between alterations in seven white matter tracts (left/right ATR, left/right SLF, forceps minor (FM) of corpus callosum and left/right IFOF) and the prevalence of sarcopenia or its diagnostic components in patients with or without diabetes mellitus, using DTI.

Methods

Participants

Patients aged ≥65 years, who had visited the Frailty Clinic at the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) and underwent brain MRI, participated in the present study. As described elsewhere, patients considered frail visit the Frailty Clinic, mainly from the endocrinology or cardiology departments 11 . We established a cohort of such patients registered consecutively, and all participants in this study were included in the registry. Diagnosis of diabetes was made by referral to the medical records, but those who had been prescribed with antidiabetic agents and those with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5% at the time of entry onto the register were also considered to have diabetes.

Patients with serious diseases, severe functional disability, advanced renal failure (serum creatinine level ≥2 mg/dL) or who had pacemakers implanted were excluded. The ethics committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital approved the study (R15‐20, 19‐03). All participants provided written informed consent.

Diagnosis of sarcopenia

Each patient’s skeletal mass index (SMI), grip strength and walking speed were measured, as described previously 11 . The patient was diagnosed with sarcopenia if they showed either low grip strength or slow walking speed, in addition to low SMI. Cut‐off thresholds for SMI, muscle strength and walking speed were set according to the latest diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, as defined by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2019 12 : low muscle mass, SMI <7.0 kg/m2 in men and <5.7 kg/m2 in women determined using bioimpedance; low muscle strength, handgrip strength <28 kg for men and <18 kg for women; and low physical performance, walking speed <1.0 m/s.

MRI acquisition

Scans of all participants were carried out using a Discovery MR750w 3.0 MRI system with a 16‐channel head coil (General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Using a single‐shot spin‐echo echo‐planar imaging sequence, DTI was carried out in the axial plane along the anterior‐posterior commissure line (66 slices without gaping, voxel size 1 × 1 × 2 mm3, field of view 256 mm, matrix size 256 × 256, number of excitations 1, repetition time/echo time 17,000/95.7 ms). The diffusion images gradient encoding schemes consisted of 32 non‐collinear directions (b‐value = 1000 s/mm2) and one non‐diffusion‐weighted image (b‐value = 0 s/mm2).

Diffusion tensor imaging analysis

The DTI data from all subjects were preprocessed using the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) 13 . First, we corrected the original DTI data from all subjects for the effects of head movement and eddy currents using eddy_correct 14 . Then, we created a brain mask by running bet 15 on the no diffusion weighting image. Finally, we fit the diffusion tensor model 13 , using dtifit, to generate fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) maps. FA and MD indicate white matter abnormalities. FA values range between 0 and 1, and a decrease in the value indicates a white matter abnormality. Conversely, an increase in the MD value indicates a white matter abnormality.

As described above, we selected seven white matter tracts as regions‐of‐interest (ROI): left/right ATR, FM, left/right IFOF, and left/right SLF. The ROI were delineated automatically on each subject’s MR image in a user‐independent fashion using FSL 13 . First, we applied non‐linear registration of all FA images to the MNI 152 standard space, provided by Montreal Neurological Institute 16 . Then, the mean FA images were drawn and thinned to create a mean FA skeleton, which represented the centers of all tracts common to the group. The aligned FA data for each subject were then projected onto this skeleton 17 . Next, we projected the FA data for all subjects onto the mean FA skeleton 17 . Finally, the Johns Hopkins University white matter tractography atlas provided with FSL was overlaid on the white matter skeleton for each subject in the MNI152 standard space, and the FA and MD values of each tract were calculated using the fslstats program 13 . Abbreviations including the terms of brain imaging are listed in Table S1.

Evaluation of other components of comprehensive geriatric assessment

Cognitive function and depressive mood were evaluated using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)‐J, and the Japanese version of Geriatric Depression Scale‐15 (GDS‐15) 18 , respectively. Physical activity was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ, www.ipar.ki.se) 19 , calculated as metabolic equivalent per week (Mets/w, sitting and lying down are excluded from physical activity). Nutritional status was evaluated using the Mini Nutritional Assessment‐Short Form (MNA‐SF) 20 .

Statistical analysis

Only the data from participants who completed both the sarcopenia screening (muscle mass, grip strength and walking speed) and an MRI scan were used for the analyses (n = 284).

Differences in categorical values were evaluated using the χ2‐test. Differences in numerical values between the two groups were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U‐test. In multiple comparisons, the P‐value was adjusted by the Bonferroni method. Furthermore, to identify the determining factor for the prevalence of sarcopenia, binomial logistic regression analyses were carried out. The FA values in regions of interest were substituted as the independent values, adjusting for age, sex, diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c, MoCA‐J score, physical activity, MNA‐SF, C‐reactive protein and GDS‐15 score.

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics 20 software package (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). In all comparisons, the significance level was P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline profiles of participants

Table 1 shows the patients’ baseline profiles. Diabetes was prevalent at a rate of 58.5%. In patients with diabetes, the median HbA1c (7.0% vs 5.8%, P < 0.001) and prevalence of dyslipidemia were higher, and serum low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol were lower, than in those without diabetes. Grip strength and SMI were slightly lower in men with diabetes than those without diabetes, but there was no statistical significance. In contrast, the SMI in women with diabetes was slightly higher than in women without diabetes. The prevalence of sarcopenia and measurements of walking speed, as well as scores of Mini‐Mental State Examination, MoCA‐J, GDS15 and physical activity, were similar in patients with and without diabetes. The MNA‐SF score was higher in diabetes patients than in those without diabetes.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants

| Total (n = 284) | Non‐DM (n = 118) | DM (n = 166) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79 (75–83) | 79 (75–83) | 79 (75–83) | 0.535 |

| Women (%) | 64.1 | 66.9 | 62.0 | 0.396 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9 (20.9–25.4) | 22.2 (20.2–25.2) | 23.3 (21.3–25.8) | 0.008 |

| Hypertension (%) | 76.1 | 78.8 | 74.1 | 0.359 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 68.3 | 55.9 | 77.1 | <0.001 |

| Stroke (%) | 10.1 | 7.0 | 12.3 | 0.143 |

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 16.1 | 13.7 | 17.9 | 0.344 |

| sBP (mmHg) | 131 (121–141) | 132 (122–141) | 131 (121–141) | 0.856 |

| dBP (mmHg) | 74 (67–82) | 73 (67–82) | 74 (66–82) | 0.833 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.0 (3.8–4.1) | 3.9 (3.8–4.1) | 4.0 (3.8–4.2) | 0.111 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.9 (12.2–13.8) | 12.9 (12.4–13.9) | 13.0 (12.0–13.8) | 0.633 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.4 (5.9–7.1) | 5.8 (5.7–6.0) | 7.0 (6.6–7.4) | <0.001 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 114 (81–156) | 108 (78–161) | 119 (83–153) | 0.644 |

| LDL‐C (mg/dL) | 107 (88–125) | 115 (95–136) | 101 (85–120) | <0.001 |

| HDL‐C (mg/dL) | 56 (47–68) | 60 (52–71) | 54 (45–65) | 0.002 |

| Cre (mg/dL) | 0.81 (0.67–1.03) | 0.80 (0.66–0.98) | 0.83 (0.69–1.03) | 0.259 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.733 m2) | 57.1 (47.2–68.7) | 59.1 (49.1–68.4) | 55.8 (45.9–69.2) | 0.516 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.07 (0.03–0.15) | 0.06 (0.03–0.13) | 0.07 (0.03–0.16) | 0.636 |

| Sarcopenia (%) | 35.9 | 33.9 | 37.3 | 0.550 |

| Grip, male (kg) | 27.5 (21.5–32.3) | 28.6 (22.5–33.4) | 26.6 (21.5–30.9) | 0.278 |

| Grip, female (kg) | 17.6 (14.7–20.9) | 18.5 (15.2–21.0) | 17.4 (14.5–20.8) | 0.144 |

| SMI, male (kg/m2) | 7.06 (6.60–7.55) | 7.19 (6.87–7.47) | 6.90 (6.55–7.59) | 0.278 |

| SMI, female (kg/m2) | 5.76 (5.28–6.23) | 5.67 (5.13–6.08) | 5.83 (5.36–6.43) | 0.051 |

| Walk speed (m/s) | 1.12 (0.95–1.28) | 1.15 (0.94–1.30) | 1.11 (0.95–1.27) | 0.627 |

| MMSE | 28.0 (26.0–29.0) | 28.0 (26.5–29.0) | 28.0 (26.0–29.0) | 0.243 |

| MoCA‐J | 21.0 (19.0–24.0) | 22.0 (19.0–25.0) | 21.0 (18.0–24.0) | 0.220 |

| GDS‐15 | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.5–7.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 0.274 |

| PA(Mets·min/week) | 1152 (396–2079) | 1188 (601–2079) | 1088 (334–2079) | 0.512 |

| MNA‐SF | 12 (10–13) | 11 (9–12) | 12 (10–13) | 0.011 |

Median and range (25–75%) are shown. Alb, albumin; BMI, body mass index; Cre, creatinine; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DM, diabetes mellitus; dBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GDS, Geriatric depression scale; Hb, hemoglobin; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MNA‐SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment‐Short Form; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PA, physical activity; sBP, systolic blood pressure; SMI, skeletal mass index; TG, triglyceride.

Tract‐specific DTI abnormalities in sarcopenia and its diagnostic elements

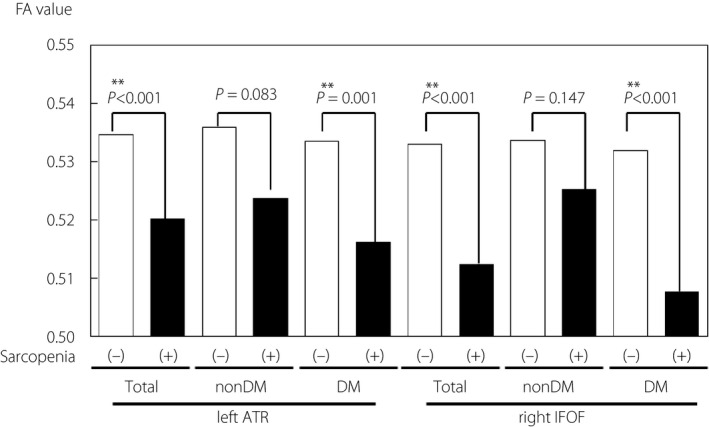

We compared FA and MD values between patients with and without sarcopenia or its diagnostic components (SMI, grip strength or walking speed), analyzing them separately by white matter tract and diabetes state, as shown in Table 2. Tracts that showed significantly lower FA or higher MD values in patients with sarcopenia, low SMI, low grip strength and low walking speed are shown. Diabetes patients with sarcopenia and low SMI showed alterations to a greater number of tracts than those without diabetes. In patients with low walking speed, many tracts were altered in both participants with diabetes and without diabetes. In patients with diabetes, the most significant white matter tract alterations occurred in the left ATR and right IFOF (Table 2, tract no. 1 and 7). Low FA and high MD values in the left ATR are significantly associated with sarcopenia, low SMI, and low grip strength. Low FA and high MD values in the right FOF are associated with sarcopenia and low walking speed. Low FA in this region is also associated with low SMI. Figure 1 shows significant associations between low FA values and sarcopenia in left ATR and right IFOF in total and diabetic patients. In non‐diabetic patients, low FA values in these tracts were associated only with low walking speed and low grip strength (left ATR), or only with low walking speed (right IFOF), but not with sarcopenia.

Table 2.

Association between tract‐specific fractional anisotropy or mean diffusivity values and sarcopenia or its diagnostic components

| Tract | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcopenia | ||||||||

| Total | FA | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.004* | 0.173 | 0.016 | 0.004* | <0.001* |

| MD | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.004* | 0.058 | 0.002* | 0.056 | 0.001* | |

| NonDM | FA | 0.083 | 0.027 | 0.113 | 0.733 | 0.384 | 0.378 | 0.147 |

| MD | 0.042 | 0.102 | 0.037 | 0.554 | 0.130 | 0.421 | 0.058 | |

| DM | FA | 0.001* | 0.002* | 0.015 | 0.042 | 0.016 | 0.002* | <0.001* |

| MD | 0.001* | 0.004* | 0.056 | 0.041 | 0.004* | 0.061 | 0.003* | |

| Low SMI | ||||||||

| Total | FA | 0.001* | <0.001* | 0.031 | 0.237 | 0.042 | 0.018 | <0.001* |

| MD | 0.001* | 0.012 | 0.071 | 0.079 | 0.012 | 0.136 | 0.008 | |

| NonDM | FA | 0.254 | 0.054 | 0.204 | 0.963 | 0.429 | 0.533 | 0.137 |

| MD | 0.113 | 0.136 | 0.150 | 0.420 | 0.206 | 0.516 | 0.113 | |

| DM | FA | 0.001* | 0.002* | 0.076 | 0.114 | 0.047 | 0.009 | 0.001* |

| MD | 0.005* | 0.044 | 0.289 | 0.088 | 0.020 | 0.137 | 0.028 | |

| Low grip strength | ||||||||

| Total | FA | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.018 | 0.007* | 0.003* | 0.002* |

| MD | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.005* | 0.003* | 0.021 | <0.001* | |

| NonDM | FA | 0.005* | 0.008 | 0.001* | 0.142 | 0.030 | 0.020 | 0.029 |

| MD | 0.009 | 0.094 | 0.001* | 0.025 | 0.006* | 0.047 | 0.014 | |

| DM | FA | 0.003* | <0.001* | 0.012 | 0.094 | 0.100 | 0.095 | 0.029 |

| MD | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.059 | 0.116 | 0.184 | 0.192 | 0.008 | |

| Low walking speed | ||||||||

| Total | FA | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.009 | 0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* |

| MD | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.007 | <0.001* | 0.001 | <0.001* | |

| NonDM | FA | 0.002* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.029 | 0.002* | 0.004* | <0.001* |

| MD | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.020 | 0.002* | 0.014 | <0.001* | |

| DM | FA | 0.021 | 0.035 | 0.006* | 0.154 | 0.069 | 0.008 | 0.004* |

| MD | 0.007* | 0.001* | 0.002* | 0.141 | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.003* | |

*Tracts that showed significant differences in fractional anisotropy (FA) or mean diffusivity (MD) values between those with/without sarcopenia and its components (multiple comparisons, the significance level P‐value was set at P ≤ 0.007, adjusted by the Bonferroni method [<0.05/7]). The numbers show white matter tracts 1, 2: left/right anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), 3: forceps minor, 4/5: left/right superior longitudinal fasciculus, 6/7: left/right inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus (IFOF). DM, diabetes mellitus.

Figure 1.

Comparison of FA values of left ATR and right IFOF between sarcopenic/nonsarcopenic patients, stratified with diabetes status. Bars show the median values of each category. ATR, anterior thalamic radiation; DM, diabetes mellitus; FA, fractional anisotropy; IFOF, inferior longitudinal fasciculus.

Binomial logistic regression analyses for sarcopenia

We performed stepwise binomial logistic regression analyses to determine the association between FA in the left ATR or right IFOF and sarcopenia, setting the prevalence of sarcopenia as the outcome variable (Table 3). In all patients and the group of patients with diabetes, the FA values of the left ATR and right IFOF were associated with sarcopenia, even after adjusting for age and gender (model 1), HbA1c, and diastolic blood pressure (model 2), MoCA score (model 3), physical activity, GDS‐15 score, MNA‐SF score, and CRP (model 4). An odds ratio per 0.1 decrease in FA for the prevalence of sarcopenia in all patients or the group of diabetic patients ranged from 4 to 8 for left ATR and from 3 to 5 for right IFOF, respectively. In contrast, the FA values of the ATR or right IFOF were not associated with sarcopenia in patients without diabetes (data not shown).

Table 3.

Association of fractional anisotropy in left anterior thalamic radiation, right inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus and sarcopenia (binomial logistic regression analyses)

| Left ATR | Right IFOF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | DM patients | Total patients | DM patients | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Model 1 | 3.65 (1.52–8.76) | 0.004 | 7.66 (2.08–28.24) | 0.002 | 2.66 (1.15–6.16) | 0.022 | 3.47 (1.10–11.00) | 0.035 |

| Model 2 | 4.66 (1.87–11.60) | 0.001 | 8.20 (2.20–30.63) | 0.002 | 3.13 (1.31–7.45) | 0.010 | 3.61 (1.11–11.72) | 0.033 |

| Model 3 | 4.48 (1.78–11.25) | 0.001 | 8.18 (2.17–30.74) | 0.002 | 3.05 (1.28–7.28) | 0.012 | 3.61 (1.11–11.75) | 0.033 |

| Model 4 | 3.76 (1.32–10.75) | 0.013 | 8.64 (1.79–41.71) | 0.007 | 2.88 (1.00–8.28) | 0.050 | 4.98 (1.03–24.00) | 0.046 |

Odds ratios of prevalence of sarcopenia are shown per 0.1 decrease of fractional anisotropy. Model 1: adjusted for age and sex; model 2: model 1 + glycated hemoglobin and diastolic blood pressure; model 3: model 2 + Montreal Cognitive Assessment; model 4: model 3 + physical activity, Geriatric Depression Scale‐15, Mini Nutritional Assessment‐Short Form and C‐reactive protein. ATR, anterior thalamic radiation; CI, confidence interval; IFOF, inferior longitudinal fasciculus; OR, odds ratio.

Since there have been some reports that usage of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, an anti‐diabetic agent, is associated with sarcopenia 21 , we further investigated the influence of the usage of antidiabetic drugs on prevlanece of sarcopenia. We found, however, that SGLT2 inhibitors were administered exclusively to patients without sarcopenia. And after we added usage of SGLT2 inhibitors, pioglitazone, biguanides or GLP‐1 receptor agonists in model 4 in diabetic patients, the associations between FA of left ATR or right IFOF and sarcopenia were hardly changed (P = 0.004–0.007, P = 0.044–0.051, respectively).

Discussion

In this study, we determined that low FA values in the left ATR and right IFOF are associated with the occurrence of sarcopenia in all patients in addition to patients with diabetes. This study’s strength is that it is the first to evaluate the association between sarcopenia or its diagnostic components and tract‐specific white matter alterations in a substantial number of patients. There have been a few reports in which the authors have observed a relationship between white matter tract damage and sarcopenia. Still, the number of patients enrolled in these studies was very small 22 , 23 . Furthermore, in this study, we analyzed the associations separately in patients with and without diabetes for the first time.

Interestingly, among the white matter tracts we tested, the patterns of association with DTI alterations or diagnostic components of sarcopenia were different between patients with and without diabetes. Following tract‐specific analyses, low SMI, as a component of AWGS 2019‐defined sarcopenia, was associated with alterations in broader regions of white matter tracts in patients with diabetes than those without diabetes, which could lead to the greater number of associations seen between local DTI differences and sarcopenia in diabetic patients (Table 2). The reason for this pattern of difference is unclear. Recently, Sugimoto et al. demonstrated that high levels of HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes are associated with muscle mass loss rather than low muscle strength or slow walking speed 24 . The accumulation of advanced glycation end‐products, due to long‐term hyperglycemia, and the impaired function of insulin, an anabolic hormone in diabetes mellitus, might be involved in the mechanism that underlies the deterioration of muscle differentiation and muscle mass loss. Since insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes could also be a strong risk factor for arteriosclerotic diseases, microvascular changes in muscle and brain could simultaneously induce muscle loss and disturb white matter integrity. However, white matter lesions in patients without diabetes may be caused by factors independent of insulin function, such as malnutrition (vitamins B1, B12, and D) and inflammation 25 , 26 .

An association between the loss of white matter integrity and slow walking speed was found in many tracts in both non‐diabetic and diabetic patients. Our results were compatible with previous reports that have demonstrated a link between white matter alterations and walking speed. de Laat et al. 27 reported that DTI abnormalities, especially those in the genu of the corpus callosum, were associated with slow walking speed in older persons. Moreover, Poole et al. found that alterations to the tracts connecting frontal lobes and other regions such as the ATR affect both the impairment of executive function and walking speed 8 . However, the mechanisms of these associations might be different between non‐diabetic and diabetic patients, i.e., in diabetic patients, some other factors independent of white matter alterations, such as diabetic neuropathy, may be related to slow walking speed.

We observed the strongest association between damage to the left ATR or right IFOF and sarcopenia or its diagnostic components in all patients and those with diabetes (Table 2, shaded boxes), and found that low FA values in both the left ATR or right IFOF were associated with sarcopenia in multivariate analyses (Table 3). Notably, the association was much stronger in diabetic patients; the odds ratios were approximately 2 and 1.5 times higher in the left ATR or right IFOF of this group than in the group containing all patients, respectively (model 4).

The association between the left ATR’s disturbed integrity and sarcopenia may be explained by impaired executive function. The ATR, which form paths through the anterior limb of the internal capsule, has reportedly been involved in executive function 28 . Executive function is impaired in patients with diabetes mellitus from the onset of mild cognitive impairment 7 . Zhang et al. 29 reported that the loss of white matter integrity in the anterior limb of the internal capsule and external capsule is associated with impaired executive function in patients with diabetes. Thus, diabetic patients seem susceptible to damage in the nerve fibers of the ATR, leading to effects in both executive function and physical performance. Indeed, altered white matter integrity in some tracts, including the ATR, affects both executive function and walking speed in the general population 8 . Furthermore, Lee et al. 23 have recently reported less white matter integrity in regions related to executive function, including the ATR, are associated with low muscle mass in Parkinson’s disease.

However, the significant association between low FA in the left ATR and sarcopenia, even after adjustment for the MoCA‐J (Table 3, model 3), in our study suggests that damage to the ATR may directly influence muscle function independently of cognitive function. The ATR consists of fibers that traverse the medial nucleus of the thalamus to the frontal lobe and pass from the anterior nucleus of the thalamus to the cingulate gyrus. More precisely, they contain fibers from the superior fronto‐occipital fasciculus, which connects the pre‐motor area and parietal lobe and is involved in somatosensory feedback 30 . These reports support the notion that damage to the ATR reduces muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance.

The IFOF reportedly connects the four (anterior, posterior, parietal, and occipital) cerebral lobes 31 . Voineskos et al. 10 commented that the right IFOF is involved in visuospatial function, thus, a disturbance in this region could affect functional decline and lead to sarcopenia, without promoting a significant decrease in the cognitive function score. (In the MoCA‐J, the score for visuospatial function accounts for only 1 out of the total 30 points). However, there has been no report suggesting that the IFOF is vulnerable, particularly in patients with diabetes, and the reason for the association between sarcopenia and the decreased FA in this tract that was observed exclusively in diabetic patients remains unclear. Further studies are required to clarify how the disturbance of white matter integrity in specific tracts affects muscle dysfunction as well as cognitive impairment in diabetic patients.

We found the influence of each tracts’ alterations on prevalence of sarcopenia were different between the hemisphere, but the reason is yet to be clarified. We could not find any previous reports indicating lateral difference of ATR damage on executive function. As for IFOF damage, severe damage in unilateral IFOF could lead to contralateral hemispatial visual neglect. Damage in right IFOF may induce impairment of left‐side recognition, but it is insufficient to explain the laterality in our subjects, a majority of those are right‐handed. However, as shown in Table 2, the pattern of left and right ATR and IFOF are mostly similar; at least the association between FA, on either side, and sarcopenia are almost the same both in total and in diabetic patients.

Some reports have shown that use of SGLT2 inhibitor is associated with skeletal muscle loss 21 . In this study, however, there was no signifinat association between treatment of SGLT2 inihibitors and sarcopenia. This could be accounted for because the physicians avoided using this drug to patients suspected to be sarcopenia not to accelerate further muscle loss in these patients. Furthermore, we found that usage of anti‐diabetic agents including SGLT2 inhibitors had little influence on the association between alterations of white matter integrity and sarcopenia in patients with diabetes.

This study has several limitations. First, as described above, due to the cross‐sectional design of this study, the causal relationship between white matter damage and sarcopenia was challenging to identify. Although we discussed structural changes in white matter as a cause of sarcopenia, the mechanism could be bidirectional. In patients with sarcopenia, a decline in physical activity could promote metabolic diseases, which, in turn, induce atherosclerotic lesions in the brain. Furthermore, in those patients, the presence of exercise‐inducible muscle‐derived peptides (myokines) that could offer some protection against inflammation and atherosclerosis may be decreased. Second, since all the participants were Frailty Clinic outpatients, those without diabetes were not completely healthy controls. As described in our previous report, most of the patients had cardiometabolic diseases and were recruited as registry study participants, which might have affected the results 12 . This could be a reason for the similar prevalence of sarcopenia between patients with and without diabetes and the higher MNA‐SF score in diabetic patients. Furthermore, because this study was performed at a single institution in Japan, our results should be verified in community‐based or multi‐centered studies.

In conclusion, we found that a loss of white matter integrity in the left ATR and right IFOF is strongly associated with the prevalence of sarcopenia in older patients with diabetes in the Frailty Clinic, which suggests an important role for these tracts in the occurrence of sarcopenia in older adults with diabetes mellitus. Further longitudinal studies are needed to clarify whether alterations to these tracts could be improved by exercise or dietary interventions to protect against sarcopenia.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1 | List of abbreviations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (28‐30) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, and The JGS Research Grant Award in Geriatrics and Gerontology from the Japan Geriatrics Society. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 18H02772. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16H06280. We thank Dr So Watanabe, Dr Koichi Toyoshima and Dr Takuya Omura for their assistance in data collection, and Mr Masahiro Cho and Ms Kanako Ito for interviewing and carrying out the physical function test, and Ms Kazuko Minowa for managing data.

J Diabetes Investig. 2021

References

- 1. IDF Diabetes Atlas 9th edition. Available from: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- 2. Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Lee JS, et al. Excessive loss of skeletal muscle mass in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1993–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Strotmeyer ES, et al. Accelerated loss of skeletal muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the health, aging, and body composition study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sarodnik C, Bours SPG, Schaper NC, et al. The risks of sarcopenia, falls and fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Maturitas 2018; 109: 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moghaddam SH, Sherbaf GF, Aarabi MH, et al. Brain microstructural abnormalities in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies. Front Neuroendocrinol 2019; 55: 100782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Assaf Y, Pasternak O. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)‐ based white matter mapping in brain research: a review. J Mol Neurosci 2008; 34: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gao Y, Xiao Y, Miao R, et al. The characteristic of cognitive function in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015; 109: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poole VN, Wooten T, Iloputaife I, et al. Compromised prefrontal structure and function are associated with slower walking in older adults. Neuroimage Clin 2018; 20: 620–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zheng Z, Shemmassian S, Wijekoon C, et al. DTI correlates of distinct cognitive impairments in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2014; 35: 1325–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Voineskos AN, Rajji TK, Lobaugh NJ, et al. Age‐related decline in white matter tract integrity and cognitive performance: a DTI tractography and structural equation modeling study. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tamura Y, Ishikawa J, Fujiwara Y, et al. Prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and sarcopenia in outpatients with cardiometabolic disease in a frailty clinic. BMC Geriatr 2018; 18: 264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21: 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, et al. Fsl. NeuroImage 2012; 62: 782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andersson JLR, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off‐resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion mr imaging. NeuroImage 2016; 125: 1063–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 2002; 17: 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, et al. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 2002; 17: 825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen‐Berg H, et al. Tract‐based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi‐subject diffusion data. NeuroImage 2006; 31: 1487–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sugishita K, Sugishita M, Hemmi I, et al. A validity and reliability study of the Japanese version of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS‐15‐J). A Validity and Reliability Study of the Japanese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS‐15‐J). Clin Gerontol 2017; 40: 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12‐country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35: 1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A, et al. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short‐form mini‐nutritional assessment (MNA‐SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M366–M372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kamei S, Iwamoto M, Kameyama M, et al. Effect of tofogliflozin on body composition and glycemic control in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res 2018; 2018: 6470137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwak SY, Kwak SG, Yoon TS, et al. Deterioration of brain neural tracts in elderly women with sarcopenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019; 27: 774–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee CY, Chen HL, Chen PC, et al. Correlation between executive network integrity and sarcopenia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sugimoto K, Tabara Y, Ikegami H, et al. Hyperglycemia in non‐obese patients with type 2 diabetes is associated with low muscle mass: The Multicenter Study for Clarifying Evidence for Sarcopenia in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2019; 10: 1471–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de van der Schueren MAE, Lonterman‐Monasch S, van der Flier WM, et al. Malnutrition and risk of structural brain changes seen on magnetic resonance imaging in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64: 2457–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Annweiler C, Bartha R, Karras SN, et al. Vitamin D and white matter abnormalities in older adults: a quantitative volumetric analysis of brain MRI. Exp Gerontol 2015; 63: 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Laat KF, Tuladhar AM, van Norden AG, et al. Loss of white matter integrity is associated with gait disorders in cerebral small vessel disease. Brain 2011; 134: 73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biesbroek JM, Kuijf HJ, van der Graaf Y, et al. SMART Study Group. Association between subcortical vascular lesion location and cognition: a voxel‐based and tract‐based lesion‐symptom mapping study. The SMART‐MR study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e60541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. White matter integrity disruptions associated with cognitive impairments in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2014; 63: 3596–3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bolandzadeh N, Liu‐Ambrose T, Aizenstein H, et al. Pathways linking regional hyperintensities in the brain and slower gait. NeuroImage 2014; 99: 7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jou RJ, Mateljevic N, Kaiser MD, et al. Structural neural phenotype of autism: preliminary evidence from a diffusion tensor imaging study using tract‐based spatial statistics. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1607–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 | List of abbreviations.