The world is currently struggling with a pandemic of novel enveloped RNA beta-coronavirus, which has currently been named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has a phylogenetic similarity to SARS-CoV and the disease it caused has been called COVID-19.

The COVID-19 can present as an asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia [1]. As of April 1, 2020, a total of 1017,693 laboratory-confirmed cases had been documented globally, including more than 53,179 deaths have been reported worldwide. Given the rate of infected people, SARS-CoV-2 is a highly contagious virus which is mainly spread though close contact with infected people via respiratory droplets from cough or sneezing. Wei et al. [2] indicated that several public health measures that may prevent or slow down the transmission of the COVID-19 were introduced; these include case isolation, identification and follow-up of contacts, environmental disinfection, and use of personal protective equipment.

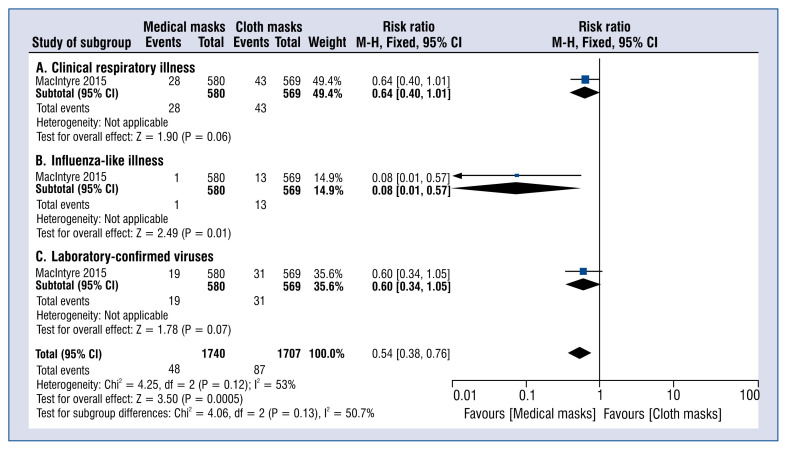

World Health Organization recommends against routinely wearing masks in community settings because of lack of evidence [3]. However, the lack of scientific evidence should not discourage people from wearing disposable face masks to limit droplet spread [4, 5]. Routine wearing of disposable masks by everyone as a public health intervention, would probably intercept the transmission link and prevent these apparently healthy infectious sources. Masks can be divided into two main groups: medical (surgical) masks and N95 respirators (designed during a pandemic mainly for high-risk medical personnel). Global shortage of medical masks is a real and expanding problem. In turn, there is growing availability on the market of cloth masks, which were used by surgeons successfully during operations before disposable masks were available. As indicated in the research published by MacIntre et al. [6] in a study on the comparison of the efficacy of cloth masks to medical masks in the context of viral infections in hospital healthcare workers, summarized that cloth masks don’t protect as well as medical masks (Fig. 1). Laboratory tests showed the penetration of particles through the cloth masks to be very high (97%) compared with medical masks (44%). A consequence of the above penetration is also a higher risk of critical care illness, the influenza-like illness is more significant in the cloth mask group than in the medical mask. Moreover, the rate of confirmation of laboratory-confirmed viruses was also much higher for cloth masks than for medical masks or groups that did not wear any mask.

Figure 1.

Results of meta-analysis determine effectiveness of medical masks versus cloth masks against respiratory infection. Outcomes are: clinical respiratory illness (A), influenza-like illness (B), laboratory-confirmed viruses (C); CI — confidence interval.

In the era of this deficit of masks, another problem arises, to which particular attention should be paid. Most people in all seriously affected areas are reusing their disposable masks. The physical properties of a cloth mask, reuse, the frequency and effectiveness of cleaning, and increased moisture retention, may potentially increase the infection risk, since, as it indicated by Osterholm et al. [7] the virus may survive on the surface of the facemasks. In this context self-contamination through repeated use and improper doffing is possible. Observations during SARS suggested double-masking and other practices increased the risk of infection because of moisture, liquid diffusion and pathogen retention [8].

Footnotes

This paper was guest edited by Prof. Łukasz K. Czyżewski

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei WE, Li Z, Chiew CJ, et al. Presymptomatic Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 — Singapore, January 23-March 16, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):411–415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in health care settings in the context of the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV) outbreak: interim guidance. [Date accessed: March 2, 2020]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330987 .

- 4.Smereka J, Szarpak L, Filipiak KF. Modern medicine in COVID-19 era. Disaster Emerg Med J. 2020 doi: 10.5603/DEMJ.a2020.0012.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smereka J, Szarpak L. COVID-19 a challenge for emergency medicine and every health care professional. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.038. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006577. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterholm M, Moore K, Kelley N, et al. Transmission of ebola viruses: what we know and what we do not know. mBio. 2015;6(2) doi: 10.1128/mbio.00137-15.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Wong T, Chung J, et al. In vivo protective performance of N95 respirator and surgical facemask. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(12):1056–1065. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]