Abstract

Introduction

Immunotherapy is the new standard of care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Recently published data show that treatment discontinuation after 12 months of nivolumab treatment is associated with shorter survival. Therefore, the ideal duration of immunotherapy remains unclear, and finding markers of beneficial outcomes is of great importance. Here, we determine the proportion of complete metabolic responses (CMR) in patients who have not progressed after 24 months of immunotherapy.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of 45 patients with positron emission tomography using 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose imaging for assessment of residual metabolic activity after at least 24 months. CMR was defined as uptake in tumor lesions below background levels, using mediastinum as a reference.

Results

Out of 45 patients, 29 patients had a CMR (64%). CMR was observed more frequently in non-first-line patients. Patients with CMR were younger (median 65.7 vs 75.5, p=0.03). Fourteen patients with CMR have discontinued therapy and have not progressed until time of analysis; however, median follow-up was only 5.6 (range 0.8–17.0) months.

Conclusion

After a minimum of 24 months of palliative immunotherapy for NSCLC, CMR occurred in almost two thirds of patients. Potentially, achievement of CMR might identify patients, for whom palliative immunotherapy may be safely discontinued.

Keywords: PET, immunotherapy, lung neoplasms, programmed cell death 1 receptor

Introduction

Recently reported, extended follow-up data from KEYNOTE-024 indicate that patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can experience long-term benefit from immunotherapy irrespective of discontinuation (per protocol: 35 cycles ∼24 months) or type of response in CT.1 Similar results were observed in the pooled analysis of 5-year follow-up data from CheckMate 017 and 057.2 This raises the question, whether patients may safely discontinue immunotherapy after achieving durable response.

However, recently published results from CheckMate-153 demonstrated inferior survival rates in patients ceasing immunotherapy after 1 year,3 therefore, optimal treatment duration of immunotherapy in advanced NSCLC remains unknown. Protocols from published phase-III trials implemented treatment for a period of approximately 24 months or until evidence of disease progression or unbearable toxicity.4–8

In malignant melanoma, complete metabolic response (CMR) on positron emission tomography using 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG-PET) yields a high negative predictive value for relapse.9 Previous studies revealed that less than 10% of patients with NSCLC achieve CMR after 2 months of immunotherapy10 and demonstrated that FDG-PET response is prognostic for progression-free survival.11 We examined whether patients with NSCLC with prolonged response to treatment with an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody had CMR and at which proportion this occurs.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective study of patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC who received therapy with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies for >24 months in absence of radiological progression. All patients underwent FDG-PET imaging for detection of residual metabolic disease between 2017 and 2020. The scans were performed for reaching an informed decision together with the patient. In the cases, where patients continued therapy despite achieving CMR, this was in accordance to the label, which allows treatment until progression or unbearable toxicity and patients’ wish to continue their treatment. A secondary rationale was to identify potential sites of disease that might benefit from local therapies (such as radiation therapy or secondary resection). This analysis was approved by the local ethics committees (reference: 20–9433-BO and Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg F-2019–092) and all patients gave written informed consent for collection of clinical data for research purposes.

Dual-modality PET-CT was performed on a Siemens Biograph mCT or a Siemens Biograph Duo System. Patients received a median dose of 300 MBq of Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (range 162–463 MBq) and were scanned after mean 63 min p.i. (range 50–123). The CT images were used for PET attenuation correction. Diagnostic CT scans with intravenous and oral contrast agent were performed except for 5 (11%) patients with a diagnostic CT scan within 4 weeks prior to the PET/CT scan, who received a low-dose CT scan and two (4%) patients with increased creatine in serum level and/or known allergic sensitivity, who did not receive intravenous contrast agent. Lesion uptake in FDG PET on or below background level (using mediastinum as reference) was considered as CMR. Time until best objective morphological response including disease stabilization was measured from start of immunotherapy until first stable CT scan (ie, no progression or further response compared with previous scan) using RECIST V.1.1.12 Categorical and continuous data were compared using Fishers exact test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. For correlation analysis, Spearman correlation test was applied.

Results

Forty-five patients were included in this analysis. Patients received nivolumab (n=21, 47%), pembrolizumab (n=20, 44 %), atezolizumab (n=3, 7 %), or ipilimumab/nivolumab (n=1, 2%). By the time of scanning, patients had received a median of 52.5 applications of immunotherapy (range 30–104) over a median period of 30.7 months (range 24.2–53.0). Prior to the PET scan, 36 (80%) and 9 (20%) of all patients have achieved partial response and stable disease by RECIST V.1.1. criteria. Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Overall (n=45) |

|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 67.6 (39.9, 84.6) |

| Gender | |

| female | 19 (42%) |

| male | 26 (58%) |

| Histology | |

| Adeno | 34 (76%) |

| Squamous | 10 (22%) |

| Sarcomatoid | 1 (2%) |

| PD-L1 expression | |

| 0 | 5 (11%) |

| >0–<10 | 0 (0%) |

| ≥10 | 28 (62%) |

| Not reported | 12 (27%) |

| T status | |

| 1 | 10 (22%) |

| 2 | 8 (18%) |

| 3 | 8 (18%) |

| 4 | 19 (42%) |

| N status | |

| 0 | 7 (16%) |

| 1 | 3 (7%) |

| 2 | 15 (33%) |

| 3 | 20 (44%) |

| M status | |

| 0 | 9 (20%) |

| 1 | 36 (80%) |

| UICC stage | |

| 3 | 9 (20%) |

| 4 | 36 (80%) |

| Immunotherapy regimen | |

| Atezolizumab | 3 (7%) |

| Nivolumab | 21 (47%) |

| Pembrolizumab | 20 (44%) |

| Ipilimumab/nivolumab | 1 (2%) |

| Treatment line | |

| First line | 25 (56%) |

| Non-first line | 20 (44%) |

| Prior surgery | 11 (24%) |

| Prior radiotherapy | 17 (38%) |

| Prior chemotherapy | 28 (62%) |

| Months immunotherapy until PET | |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 30.7 (24.2, 53.0) |

| Months until best objective response | |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 10.4 (1.1, 30.1) |

| Response according to RECIST | |

| PR | 36 (80%) |

| SD | 9 (20%) |

PET, positron emission tomography.

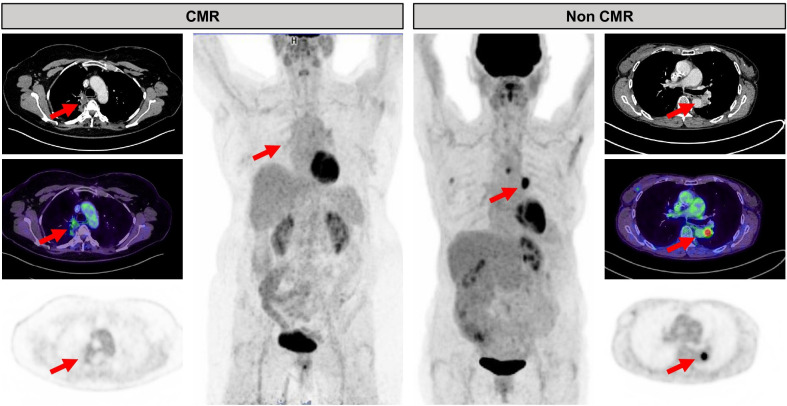

Twenty-nine patients (64%) had CMR identified by PET. Residual metabolic activity was located in the lungs (11/16, 69%), lymph nodes (12/16, 75%), pleura (4/16, 25%), or adrenal gland metastasis (1/16, 6%). Figure 1 shows one representative case each for CMR and non-CMR. Patients with CMR were younger (median 65.7 vs 75.7, p=0.03). CMR was observed more frequently in non-first-line patients (12/25 and 17/20 in first-line patients and non-first-line patients, respectively, p=0.01). In our cohort, neither histology nor PD-L1 expression predicted CMR. There was no significant correlation between target lesion size and FDG uptake (rho 0.05; p=0.76, see online supplemental figure 1). Table 2 shows patients’ characteristics stratified by response groups.

Figure 1.

Example of a patient with CMR (left) and non-CMR (right). Red arrows indicate residual tumor visible on CT. The patient on the left has uptake below background rated as CMR (see mediastinum for reference), whereas the patient on the right exhibits intense focal uptake rated as residual metabolic disease or non-CMR. CMR, complete metabolic response.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics separated by CMR vs non-CMR

| CMR (n=29) |

Non-CMR (n=16) |

P value | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 65.7 (39.9, 82.0) | 75.5 (58.3, 84.6) | 0.03 |

| Gender | |||

| female | 13 (45%) | 6 (38%) | |

| male | 16 (55%) | 10 (62%) | 0.63 |

| Histology | |||

| Adeno | 23 (79%) | 11 (69%) | |

| Squamous | 5 (17%) | 5 (31%) | |

| Sarcomatoid | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.65 |

| PD-L1 expression | |||

| 0 | 5 (17%) | 0 (0%) | |

| >0–<10 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ≥10 | 17 (59%) | 11 (69%) | 0.27 |

| Not reported | 7 (24%) | 5 (31%) | |

| T status | |||

| 1 | 6 (21%) | 4 (25%) | |

| 2 | 5 (17%) | 3 (19%) | |

| 3 | 7 (24%) | 1 (6%) | |

| 4 | 11 (38%) | 8 (50%) | 0.57 |

| N status | |||

| 0 | 7 (24%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 1 | 2 (7%) | 1 (6%) | |

| 2 | 9 (31%) | 6 (38%) | |

| 3 | 11 (38%) | 9 (56%) | 0.17 |

| M status | |||

| 0 | 4 (14%) | 5 (31%) | |

| 1 | 25 (86%) | 11 (69%) | 0.24 |

| UICC stage | |||

| 3 | 5 (17%) | 4 (25%) | |

| 4 | 24 (83%) | 12 (75%) | 0.70 |

| Immunotherapy regimen | |||

| Atezolizumab | 1 (3%) | 2 (12%) | |

| Nivolumab | 16 (55%) | 5 (31%) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 12 (41%) | 8 (50%) | |

| Ipilimumab/nivolumab | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0.15 |

| Treatment line | |||

| First line | 12 (41%) | 13 (81%) | |

| Non-first line | 17 (59%) | 3 (19%) | 0.01 |

| Prior surgery | 9 (31%) | 2 (12%) | 0.28 |

| Prior radiotherapy | 13 (45%) | 4 (25%) | 0.19 |

| Prior chemotherapy | 21 (72%) | 7 (44%) | 0.06 |

| Months immunotherapy until PET | |||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 30.8 (24.2, 53.0) | 30.0 (24.2, 50.5) | 0.90 |

| Months until best objective response | |||

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 7.8(1.1, 26.0) | 11.1(3.0, 30.1) | 0.12 |

| Response according to RECIST | |||

| PR | 24 (83%) | 12 (75%) | |

| SD | 5 (17%) | 4 (25%) | 0.7 |

CMR, complete metabolic response; PET, positron emission tomography.

jitc-2020-002262supp001.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)

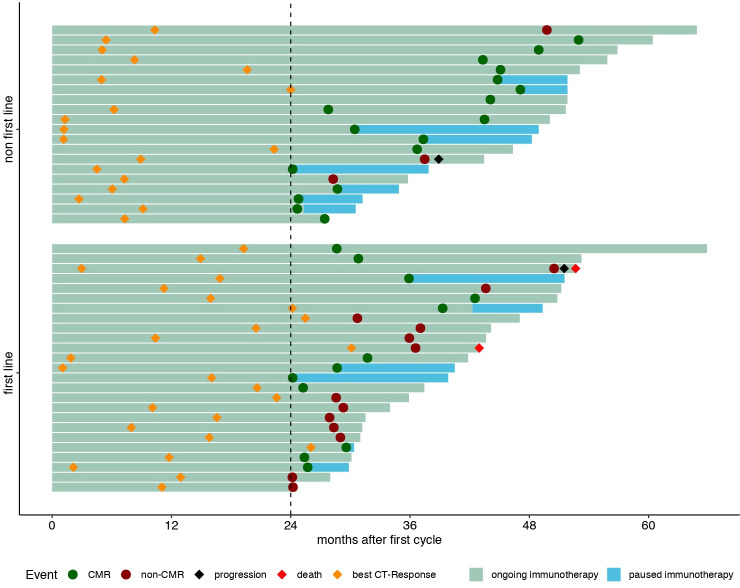

None of the patients with CMR has progressed or died until time of analysis. One non-CMR patient progressed during follow-up. Two patients with residual metabolic disease died before time of analysis (median follow-up after PET 6.0 months, range 0.13–35.8). One patient had tumor cachexia, esophageal stenosis and ultimately refused parenteral nutrition. The other patient died without evident disease progression, most likely due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Fourteen patients with CMR discontinued immunotherapy following FDG PET. In this cohort, median follow-up was 5.6 (range 0.8–17.0) months. Figure 2 shows a swimmer plot of patients’ events since start of immunotherapy.

Figure 2.

Swimmer plot of long-term responders to immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. CMR, complete metabolic response.

Discussion

Long-term, relapse-free survival in patients with incomplete response to checkpoint inhibitor therapy raises the question whether residual lesions are a sign of vital disease or remnant scar tissue. However, in most cases, pathologic evaluation of all lesions is not feasible. Furthermore, in contrast to other entities such as Hodgkin lymphoma, in lung cancer, FDG-PET is not an established tool to divide between nonvital and vital lesions.13 As a consequence, duration of therapy in phase-III protocols varied. While some stopped therapy after approximately 2 years,6 others continued until progression or unacceptable toxicity.14

Immune effects mimicking disease progression (referred to as pseudoprogression) pose an obstacle for the response assessment of immunotherapy. This most often occurs during the first 12 weeks after treatment initiation and is more frequent for CTLA-4 inhibitors compared with PD-1 inhibitors or PD-L1 inhibitors.15 Despite this, immune reactions must be kept in mind as a potential pitfall. One patient in our cohort had residual metabolic disease only in thoracic lymph nodes (online supplemental figure 2) and, therefore, rated as non-CMR; however sarcoid-like reaction must be considered as a potential pitfall.16 In contrast to this, lung adenocarcinoma subtypes with low-to-moderate FDG uptake could render false-negative results.17

jitc-2020-002262supp002.pdf (113.4KB, pdf)

Patient characteristics differed between patients with CMR and non-CMR. Furthermore, patients who achieved CMR were significantly younger than patients who had residual metabolic disease. This may point to a relevant role of immunosenescence in the context of CMR. Although a review of available retrospective analyses or real-world data confirmed a benefit of elderly patients from immune checkpoint inhibitors,18 the effect of age on CMR has not been addressed previously. Of note, CMR rates did not differ between patients achieving stable disease and patients achieving partial response.

The finding that CMR was observed more frequently in patients who received second-line immuno-oncological therapy after first-line chemotherapy could hint at a possible benefit of (sequential) use of chemo and immune therapy. Of note, none of the patients in this analysis had combined chemoimmunotherapy, given the approval of combination therapy in Europe in late 2019. However, given the retrospective nature of this study, we cannot provide mechanistic insights into this observation.

Most prior investigations have evaluated early responses (approximately 4–12 weeks) of NSCLC to immunotherapy and observed less than 10% of patients achieving CMR.10 Evidence of CMR in solid tumors following a longer period of immunotherapy has been provided previously in malignant melanoma. Tan et al demonstrated, that after 12 months of immunotherapy, 68% of patients with melanoma with partial response in CT had CMR in FDG-PET.9 In their analysis, CMR was associated with longer progression-free survival when compared with patients with non-CMR (HR 0.07, p<0.001). A fraction of patients with CMR maintained their response despite discontinuation of checkpoint inhibitor therapy, thereby linking CMR to durable response.9 In our study, we observe a similar rate of CMR following at least 24 months of immunotherapy, possibly indicating that CMR by FDG-PET may serve as a predictor for patients with long-term response.

Although a prospective study indicated that treatment discontinuation was associated with detrimental survival in NSCLC,3 CMR by FDG-PET selects a patient population with favorable response to treatment. In the presented cohort of patients, 15 of 27 (56%) patients with CMR have paused immunotherapy following FDG-PET, none of them has progressed. Although median follow-up is short, patients with CMR might be suitable for treatment discontinuation. In analogy to consolidation radiotherapy of residual PET-positive disease after treatment in (Hodgkin) Lymphoma,19 it is interesting to speculate whether patients who do not achieve a CMR might benefit from local ablative therapy of PET-positive residual disease. We hypothesize that 24 months without progression after starting immunotherapy is an appropriate point of time to perform FDG-PET for the restaging of patients, since there is little data on how to manage patients beyond 2 years of immunotherapy and since we do not observe difference in CMR rates in patients with a longer period of immunotherapy.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, our cohort study is the first to present data on the metabolic response after long-term disease stabilization on immune therapy in NSCLC, providing important data for the discussion of immuno-oncological treatment beyond 24 months. This study is limited primarily by its retrospective design, its small sample size, and the limited follow-up period after PET-CT. Prospective trials are needed to shed light on PET-guided treatment modification in patients with durable response following immunotherapy for advanced NSCLC.

Conclusion

In summary, FDG-PET reveals CMR in about two thirds of patients with prolonged but incomplete CT response. High-level evidence is now needed to determine the prognostic value of FDG-PET following immunotherapy. Potentially, FDG-PET could facilitate safer treatment discontinuation or consideration of additional local ablative therapy for persisting metabolically active tumor residuum.

Footnotes

MF and DCC contributed equally.

Correction notice: This paper has been updated since first published to amend author and funding details.

Contributors: Conception and design of study: JF, DCC and MF. Acquisition of data: JF, LK, KOK, DCC, MF. Analysis and interpretation of data: JF, DCC, MF, WPF. Writing and review of manuscript: JF, LK, MM, LU, CA, KOK, VG, WE, WPF, KH, MF and DCC.

Funding: JF has received a Junior Clinician Scientist Stipend granted by the University Duisburg-Essen. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Competing interests: MM reports personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Roche and Takeda. LK is a consultant for AAA and BTG and received fees from Sanofi, all outside of the submitted work. LU is a speaker for Bayer Healthcare, a speaker for Siemens Healthcare and has received research grants from Siemens Healthcare outside of the submitted work. CA reports grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work. KK reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from BMS, grants and personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. VG reports personal fees and other from MSD, personal fees and other from Bristol Myers Squibb, personal fees and other from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Ipsen, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from MSD Oncology, personal fees from Merck Serono, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from PharmaMAr, personal fees from EUSA Pharma, personal fees from Janssen-Cilag, outside the submitted work. WEE reports grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from GlaxiSmithKline, personal fees from Astellas, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Merck Serono, personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, personal fees from Hexal, outside the submitted workKH reports personal fees from Bayer, personal fees and others from Sofie Biosciences, personal fees from SIRTEX, non-financial support from ABX, personal fees from Adacap, personal fees from Curium, personal fees from Endocyte, grants and personal fees from BTG, personal fees from IPSEN, personal fees from Siemens Healthineers, personal fees from GE Healthcare, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from ymAbs, outside the submitted work. WPF is a consultant for Endocyte and BTG, and he received fees from RadioMedix, Bayer, and Parexel outside of the submitted work. MF has received speaker’s honoraria and participated as PI in clinical trials of AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD, and BMS. DCC reports personal fees, non-financial support and others from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Takeda.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified patient data are available upon reasonable request. In this case, please contact Dr. Ferdinandus (justin.ferdinandus@uk-essen.de).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This analysis was approved by the local ethics committees (Reference: 20–9433-BO and Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg F-2019–092) all patients gave written informed consent for collection of clinical data for research purposes.

References

- 1.Brahmer JR, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. LBA51 KEYNOTE-024 5-year OS update: First-line (1L) pembrolizumab (pembro) vs platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) in patients (pts) with metastatic NSCLC and PD-L1 tumour proportion score (TPS) ≥50%. Annals of Oncology 2020;31:S1181–2. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gettinger S, Borghaei H, Brahmer J, et al. OA14.04 five-year outcomes from the randomized, phase 3 trials CheckMate 017/057: nivolumab vs docetaxel in previously treated NSCLC. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2019;14:S244–5. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waterhouse DM, Garon EB, Chandler J, et al. Continuous versus 1-year Fixed-Duration nivolumab in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate 153. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:JCO2000131:3863–73. 10.1200/JCO.20.00131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borghaei H, Brahmer J. Nivolumab in Nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;374:493–4. 10.1056/NEJMc1514790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1540–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (oak): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:255–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan AC, Emmett L, Lo S, et al. Fdg-Pet response and outcome from anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018;29:2115–20. 10.1093/annonc/mdy330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldfarb L, Duchemann B, Chouahnia K, et al. Monitoring anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer with FDG PET: introduction of iPERCIST. EJNMMI Res 2019;9:8. 10.1186/s13550-019-0473-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaira K, Higuchi T, Naruse I, et al. Metabolic activity by 18F-FDG-PET/CT is predictive of early response after nivolumab in previously treated NSCLC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45:56–66. 10.1007/s00259-017-3806-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallamini A, Tarella C, Viviani S, et al. Early chemotherapy intensification with Escalated BEACOPP in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma with a positive interim positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan after two ABVD cycles: long-term results of the GITIL/FIL HD 0607 trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:454–62. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Cell surface glycoprotein of reactive stromal fibroblasts as a potential antibody target in human epithelial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990;87:7235–9. 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong ANM, McArthur GA, Hofman MS, et al. The advantages and challenges of using FDG PET/CT for response assessment in melanoma in the era of targeted agents and immunotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017;44:67–77. 10.1007/s00259-017-3691-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheshire SC, Board RE, Lewis AR, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced Sarcoid-like reactions during treatment of metastatic melanoma. Radiology 2018;289:564–7. 10.1148/radiol.2018180572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura H, Saji H, Shinmyo T, et al. Close association of IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma subtypes with glucose-uptake in positron emission tomography. Lung Cancer 2015;87:28–33. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casaluce F, Sgambato A, Maione P, et al. Lung cancer, elderly and immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S1474–81. 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, et al. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin's lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012;379:1791–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61940-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2020-002262supp001.pdf (14.5KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-002262supp002.pdf (113.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified patient data are available upon reasonable request. In this case, please contact Dr. Ferdinandus (justin.ferdinandus@uk-essen.de).