In the two decades since “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” was issued by the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine-NAM), advances in patient safety have focused mainly on inpatient settings whereas outpatient settings have been overlooked. However, accumulated evidence leaves little justification to continue neglecting ambulatory safety.1 A systematic review from 2015 estimated that safety incidents, such as those related to administrative and communication issues, missed/delayed diagnosis, and prescribing and medication management errors, occur in median of 2–3 incidents per 100 primary care visits.2 Other studies have estimated that 5% of US adult outpatients may have experienced a diagnostic error annually,3 and that a projected 4.5 million ambulatory care visits annually in US may have been related to an adverse drug event.4 Although errors in ambulatory settings are less likely to lead to immediate harm than errors in acute/inpatient care, their health consequences may be significant nonetheless (e.g., from missed cancer diagnosis). Recognizing the need to address outpatient safety, reports from national and international groups, including the NAM, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), American Medical Association, American College of Physicians, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and World Health Organization, have offered an impetus to develop mechanisms to measure ambulatory patient harm, prioritize near-term goals, and create high-profile initiatives similar to inpatient settings.1

Several barriers limit progress toward next steps. Care fragmentation and inadequate data systems make it difficult to map longitudinal patient experience in and across multiple settings (e.g., primary/specialty care, patient home, diagnostic testing, community-pharmacy), hindering detection and assessment of safety problems. Consider a patient who, after visiting primary care and multiple specialty care settings, two laboratories, an imaging center, and an ambulatory surgery center, is diagnosed with lung cancer one year after initially presenting with complaints of fatigue and weight loss. Identifying this event and then determining sources of diagnostic delay in this patient’s clinical course is a challenging task even if medical records from each setting are easily accessible. Resources, infrastructure for measurement and analytics, and accreditation requirements for safety are less developed for ambulatory settings compared with inpatient settings. Additionally, patients can have complex presentations that include undifferentiated symptoms, multiple chronic conditions, and social needs that warrant attention in time-pressured, information-poor work environments.

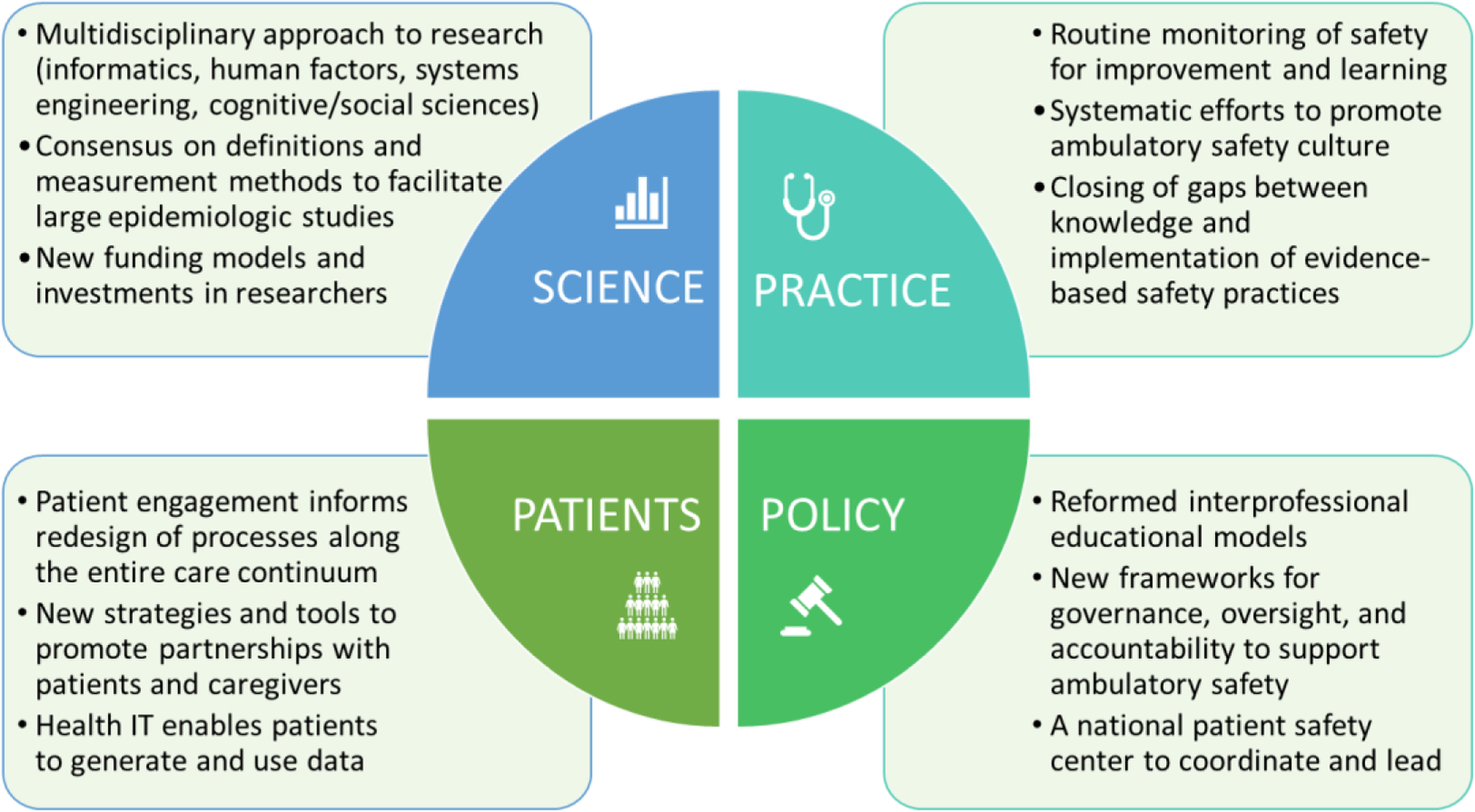

While the limitations of existing measurement methods have made it difficult to precisely quantify the overall prevalence of harm, evidence suggests that medication errors, diagnostic errors, and communication and coordination breakdowns are the most common causes of preventable harm among outpatients. The scope and consequences of harm include physical, psychological, and/or financial harms to patients, caregivers, health care workers, and society. A roadmap of milestones is needed to accelerate progress (Figure).

Figure:

Selected Key Milestones to Advance Ambulatory Safety

Science Milestones

Ambulatory care is now understood as a complex, adaptive sociotechnical system with patient care distributed over time, space, and settings.5 Improving ambulatory safety requires a multifaceted systems approach that accounts for technologies, processes, physical environments, organizational structures, and human interaction.5 For instance, information technology (IT) may seem an obvious solution to some safety concerns, but implementation of health IT has outpaced knowledge of how to optimize its safe use, and evidence suggests that health IT introduces new and unique potential harms.6 Harmful outpatient diagnostic delays have been associated with mismanagement of electronic health record (EHR) inbox notifications, delayed/inadequate electronic communication, lack of interoperability and poor usability.6 Increasing use of health IT (e.g., apps) by patients has also raised new safety concerns.7 To address complexity of ambulatory safety, multidisciplinary scientific efforts are needed and should include clinicians and experts in health informatics, human factors, systems engineering, cognitive sciences, and social and behavioral sciences.

Methods to study ambulatory safety include chart reviews, administrative data, reports from clinicians and patients, observations and surveys but each provides a limited view. Inconsistent definitions of safety events and harm have made comparisons difficult across studies. Achieving consensus around definitions and measurement methods will enable larger epidemiologic studies to quantify harm more precisely. Mixed-methods studies could help develop and assess safety interventions in diverse ambulatory settings, including patients’ homes.

Research funding for studying outpatient safety is limited and largely supported by AHRQ, Veterans Health Administration, and some philanthropic organizations. Additional investments and new research funding models could help develop pathways to implementation through strong partnerships between researchers, clinicians, adminstrators, and patients. A parallel effort to support career development could reverse the decline in early-career researchers dedicated to studying patient safety.

Practice Milestones

Meaningful measures of outpatient safety remain underdeveloped. Thus, practices should focus measurement efforts on internal quality improvement and learning activities and not be subjected to regulatory requirements for reporting pre-specified measures of questionable value. Various data sources can inform improvement and learning. Some practices have implemented safety incident reporting systems to detect events, but reporting is low. Of 1.5 million reports submitted to a federally-listed Patient Safety Organization (PSO) over a 6-year period, only 2.5% involved outpatient settings and less than half of participants shared any outpatient event.8 Engaging physicians, minimizing data-entry requirements, linking reports to action and provision of financial support for these systems could improve uptake. To strategically monitor safety and learn from past events with potential and real harm, practices could perform selective medical record reviews using automated detection techniques such as “e-triggers” that mine EHR data to identify harm and/or proactively monitor for high-risk conditions.1 PSOs can offer confidential data gathering and analytic capabilities, especially for smaller practices. In the future, standardized and validated safety metrics will need to be developed nationally and expanded to include patient perspectives.

Safety interventions are most likely to succeed within a practice culture that promotes reporting of errors and near-misses without concerns about negative consequences for reporting. However, AHRQ safety culture surveys involving 18,396 respondents (clinicians and administrative support staff) from 1,475 medical offices found that 34% perceived that their mistakes are held against them, reinforcing the need to promote a culture of safety.9 Organizations must protect clinicians/staff who report safety incidents and promote a culture that balances individual accountability with attention to underlying system vulnerabilities.

Interventions to minimize health IT-related harm require forging stronger collaborations among clinicians, reseachers, IT specialists, human factors professionals, and vendors to improve design, usability, and functionality. A well-integrated and interoperable information infrastructure is also overdue and could enable use of technologies that automate information acquisition (e.g., sensors) and analysis (e.g., algorithms) and provide cognitive support for decision-making.

Evidence-based strategies to prevent medication errors, failures in teamwork, problems with communication and coordination, and breakdowns in follow-up of test results and referrals have emerged but implemented inconsistently.1,6,10 To close gaps between knowledge and implementation, outpatient practices need dedicated time, training, incentives, and resource support. To enable change, large integrated delivery systems could leverage their infrastructure to create ambulatory safety programs and become learning centers that test and implement safety strategies. Multi-site collaboratives10 could also be developed to implement and share promising innovative approaches to address high-risk areas. A newly created national knowledge platform could serve as a repository for both existing and emerging evidence-based strategies to facilitate implementation.

Policy Milestones

To address complexities of ambulatory care, future workforce competencies could emphasize systems thinking, while incorporating interprofessionalism and team-based care. This would require substantial reform of models of health professions education that focus on disease-based care. Payment policies currently focused on patient volumes should place greater emphasis on safety. To overcome common barriers such as inertia, lack of leadership support, resources and dedicated teams to identify and mitigate risks, policy initiatives should build robust frameworks for governance, oversight, and accountability. Accreditation bodies and payers could adopt more effective models to promote routine safety measurement and learning and leverage both intrinsic motivation of clinicians and extrinsic incentives to improve safety. Long overdue is the development of a national patient safety center that would be charged with independently setting and executing a safety agenda, collecting and analyzing data from health systems and patients, and converting this intelligence into actionable solutions. Such a collaborative oversight body is needed to ensure shared accountability and to establish national leadership for ambulatory safety.

Patients and Caregivers Milestones

Meaningful engagement of patients can inform redesign of processes along the entire care-continuum.5 New strategies to help practices partner with patients and caregivers to improve safety could be promoted through public-focused campaigns, patient advocates, and professional societies. High-intensity engagement efforts could especially focus on patients at elevated risk (e.g., older, with multi-morbidity, and/or adversely affected by social determinants of health).

One strategy for gathering safety data from patients is to modify existing patient-experience surveys. Additionally, health IT has opened new channels for patients to generate and use data, including patient portals to access test results and other health information, options to report safety concerns, self-triage and diagnosis tools for symptom-checking, and self-management support. Usability principles and rigorous evaluation should guide subsequent development and implementation.

Conclusion

The time to accelerate initiatives to reduce preventable harm in the outpatient setting has arrived. Key milestones related to scientific advances, practice improvements, policy changes, and strategies to partner with patients and families can accelerate meaningful advances to reduce patient harm in ambulatory care.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Singh is funded in part by the Houston Veterans Administration (VA) Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety (CIN13-413), the VA HSR&D Service (CRE17-127 and the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers USA 14-274), the VA National Center for Patient Safety, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS27363), the CanTest Research Collaborative funded by a Cancer Research UK Population Research Catalyst award (C8640/A23385) and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Dr. Carayon is funded in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS022086; R18HS026624), and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (UL1TR002373). We thank Andrea Bradford, PhD for assistance with medical editing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- 1.Bates DW, Singh H. Two decades since To Err Is Human: An assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(11) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panesar SS, deSilva D, Carson-Stevens A, et al. How safe is primary care? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:544–53.doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh H, Meyer AN, Thomas EJ. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: Estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual Saf. 9/2014 2014;23(9):727–731. doi:bmjqs-2013–002627 [pii]; 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002627 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar U, López A, Maselli J, Gonzales R. Adverse drug events in U.S. adult ambulatory medical care. Health services research. 2011 October 2011;46(5)doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carayon P, Wooldridge A, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Kelly MM. SEIPS 3.0: Human-centered design of the patient journey for patient safety. Appl Ergon. April 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.103033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell L, Sittig DF, Chrouser K, Singh H. Assessment of health information technology-related outpatient diagnostic delays in the US Veterans Affairs health care system: A qualitative study of aggregated root cause analysis data. JAMA Netw Open. June 2020;3(6):e206752. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millenson ML, Baldwin JL, Zipperer L, Singh H. Beyond Dr. Google: The evidence on consumer-facing digital tools for diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl). September 25 2018;5(3):95–105. doi: 10.1515/dx-2018-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma A, Yang J, Del Rosario J, Hoskote M, Rivadeneira N, Sarkar U. What safety events are reported for ambulatory care? Analysis of incident reports from a Patient Safety Organization. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2020; Journal Pre-Proof. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Famolaro T, Hare R, Thornton S, Yount ND, Fan L, Liu H, Sorra J. Surveys on Patient Safety Culture™ (SOPS™) medical office survey: 2020 user database report. (Prepared by Westat, Rockville, MD, under Contract No HHSP233201500026I); Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2020. AHRQ Publication No. 20–0034. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiff GD, Reyes Nieva H, Griswold P, et al. Randomized trial of reducing ambulatory malpractice and safety risk: Results of the Massachusetts PROMISES Project. Med Care. August 2017;55(8):797–805. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]