Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of corticosteroids among older adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia requiring oxygen.

Methods

We used routine care data from 36 hospitals in France and Luxembourg to assess the effectiveness of corticosteroids with at least 0.4 mg/kg/day equivalent prednisone (treatment group) versus standard of care (control group). Participants were adults aged 80 years or older with PCR-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection or CT scan images typical of COVID-19 pneumonia, requiring oxygen ≥3 L/min, and with an inflammatory syndrome (C-reactive protein ≥40 mg/L). The primary outcome was overall survival at day 14. In our main analysis, characteristics of patients at baseline (i.e. time when patients met all inclusion criteria) were balanced by using propensity-score inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Results

Among the 267 patients included in the analysis, 98 were assigned to the treatment group. Their median age was 86 years (interquartile range 83–90 years) and 95% had a SARS-CoV-2 PCR-confirmed diagnosis. In total, 43/98 (43.9%) patients in the treatment group and 84/166 (50.6%) in the control group died before day 14 (weighted hazard ratio 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.99). The treatment and control groups did not differ significantly for the proportion of patients discharged to home/rehabilitation at day 14 (weighted relative risk 1.12, 95% CI 0.68–1.82). Twenty-two (16.7%) patients receiving corticosteroids developed adverse events, but only 11 (6.4%) from the control group.

Conclusions

Corticosteroids were associated with a significant increase in the overall survival at day 14 of patients aged 80 years and older hospitalized for severe COVID-19.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Corticosteroids, Elderly, Observational study, Therapeutic evaluation

Introduction

The RECOVERY trial showed that dexamethasone reduced mortality for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) receiving oxygen with and without invasive mechanical ventilation [1]. The efficacy of corticosteroids in critically ill patients was confirmed in subsequent studies [[2], [3], [4]]. However, for patients with less severe disease, studies have shown variable effectiveness, associated with the severity of the disease: the more severely ill the patients, the more effective the treatment [1,5,6].

In older adults, who are at the greatest risk of severe disease and death from COVID-19, the RECOVERY trial is the only study reporting results for patients outside critical care, and it found no difference in the survival of patients according to their treatment by dexamethasone [1,7]. Nonetheless, the heterogeneity in the severity of infection within this specific subgroup does not justify strong conclusions. The unclear benefit–risk balance of corticosteroids for older patients has raised concerns (e.g. because these drugs increase the risk of confusion, hyperglycaemia, falls, drug–drug interactions), and some countries, including France, do not support the systematic use of corticosteroids for patients aged ≥70 years despite recommendations from the WHO to treat all adult patients with severe and critical COVID-19 with systemic corticosteroids [8].

In this study, we used routine care data collected during the first acute phase of the pandemic to retrospectively emulate a target trial aimed at assessing the effectiveness of corticosteroids for severe infections with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in older adults.

Materials and methods

Participants and settings

Physicians screened one by one all patients hospitalized between 14 March and 30 April, 2020. First, they identified all consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, with a SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by PCR or by typical clinical and CT scan findings. Second, they assessed whether these patients had a severe COVID-19 infection, defined by both an oxygen requirement ≥3 L/min (regardless of its duration) and C-reactive protein ≥40 mg/L [9]. Third, they excluded patients with organ failure at baseline, including those who required immediate admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and those requiring non-invasive ventilation. Physicians and research assistants then used patients' electronic health records to abstract their data.

The Institutional Review Board of Henri-Mondor Hospital (AP-HP), France, approved this study (number: 00011,558). As it was based on data from routine care already collected at the time of the study, patients' informed consent was not required. All patients or family members were informed that their hospital data would be used for research purposes and were offered the opportunity to object to the use of their data.

Treatment strategies

We compared two treatment strategies: receiving at least one dose of corticosteroids at ≥0.4 mg/kg/day equivalent prednisone (treatment group), or receiving the standard of care (control group). The cut-off value of 0.4 mg/kg/day was chosen to account for dose rounding by physicians. To mimic a pragmatic trial, patients in the treatment group could start corticosteroids within a ‘grace period’ of 72 hours from baseline.

Our causal contrast of interest was the per-protocol effect, and we compared participants who received corticosteroids in the 72 hours after baseline with those who did not receive this drug. A specific sensitivity analysis mimicking an intention-to-treat analysis was performed, analysing all patients eligible for the study; those whose data did not meet the criteria for treatment were analysed in the control group. For safety outcomes, all patients who received corticosteroids before day 14, regardless of the dose or timing, were included in the treatment group. The definition of group assignment based on patients' observational data is reported in the Supplementary material (Table S1).

Follow up

The start of follow up (baseline or time zero) for each individual was the time when all eligibility criteria (oxygen therapy ≥3 L/min and inflammatory syndrome with a C-reactive protein level ≥40 mg/L) were met. All patients were followed up from baseline until the occurrence of one of the following events, whichever came first: (a) death, (b) loss to follow up, or (c) end of follow up, which occurred at least 14 days after baseline.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was overall survival by day 14. The secondary outcome was the proportion of patients discharged from hospital to home/rehabilitation on day 14. The time frame of 14 days was chosen because at the time of the study and in the frail population of patients ≥80 years old, most deaths occurred before day 14 [10]. All adverse events were abstracted from electronic health records in free text and independently recoded by one physician (VTT).

Statistical analyses

Propensity-score methods were used to account for differences between the two groups at baseline. The propensity score represents the probability that patients would receive corticosteroids, given their baseline demographic and clinical covariates (see Supplementary material, Appendix S2). Estimates of the average treatment effect were calculated by inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), with Cox proportional hazards models calculating hazard ratios and IPTW estimates of the relative risk for binary outcomes.

To account for immortal time bias, all patients in the control group who died during the grace period were randomly assigned to one of the two groups, given that their observational data were compatible with both groups at the time of the event (see Supplementary material, Appendix S3) [11,12].

Missing baseline variables were handled by using multiple imputation with chained equations.

Results

Participants

This study included 267 patients. Their median age was 86 years (interquartile range (IQR), 83–90 years), 49.8% were men, 95% had a SARS-CoV-2 PCR-confirmed diagnosis and 98 were assigned to the treatment group (see Supplementary material, Figs S1–S3 and Table S2). Co-morbidities and clinical severity at baseline were similar between the two groups. However, corticosteroids were prescribed less often to patients with low autonomy at baseline, measured with the Groupe Iso Ressource score; 14.3% of patients in the treatment group and 20.9% in the control group had a Groupe Iso Ressource score of 1 or 2, which indicates low autonomy.

The median time from symptom onset to baseline was 7 days (IQR 4–10). Among the 98 patients assigned to the treatment group, 51 (53.7%) received methylprednisolone, 22 (23.2%) prednisone, 15 (15.8%) dexamethasone, 4 (4.2%) prednisolone and 3 (3.2%) hydrocortisone. The median duration of corticosteroid treatment was 5 days (IQR 3–11) and the median dose of corticosteroids 1.1 mg/kg/day eq. prednisone (IQR 0.9–1.6), that is, 0.2 mg/kg of dexamethasone per day (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Patients' baseline characteristics (n = 267)

| Characteristics | Total (n = 267) | Treatment group (n = 98)a |

Control group (n = 169) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical data | |||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 86 (83−90) | 86 (83−89) | 87 (83−90) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 133 (49.8) | 48 (49.0) | 85 (50.3) |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease (including asthma) | 17 (6.4) | 6 (6.1) | 11 (6.5) |

| Chronic heart failure (n = 247) | 111 (41.6) | 44 (44.9) | 67 (39.6) |

| Cardiovascular diseases (including hypertension) (n = 266) | 228 (85.7) | 85 (87.6) | 143 (84.6) |

| Chronic kidney failure | 48 (18.0) | 21 (21.4) | 27 (16.0) |

| Diabetes requiring insulin or complicated (n = 260) | 39 (15.0) | 12 (12.5) | 27 (16.5) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Immunosuppression | 10 (3.7) | 4 (4.1) | 6 (3.6) |

| Cancer | 27 (10.2) | 7 (7.1) | 20 (11.9) |

| Body weight (kg), median (IQR) (n = 204) | 71 (61–79) | 72 (62–80) | 70 (60–78) |

| Autonomy (GIR score), n (%) (n = 261) | |||

| GIR score 1 or 2 (Low autonomy) | 48 (18.4) | 14 (14.3) | 34 (20.9) |

| GIR score 3 or 4 (Moderate autonomy) | 78 (29.9) | 36 (36.7) | 42 (25.8) |

| GIR score 5 or 6 (High autonomy) | 135 (51.7) | 48 (49.0) | 87 (53.4) |

| Usual place of residence, n (%) | |||

| Community | 183 (68.5) | 64 (65.3) | 119 (70.4) |

| Retirement homes | 19 (7.1) | 7 (7.1) | 12 (7.1) |

| Nursing homes/Hospital | 62 (23.2) | 26 (26.5) | 36 (21.3) |

| Other | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) |

| Treatment by ACEIs or ARBs, n (%) (n = 258) | 119 (46.3) | 39 (40.6) | 80 (49.4) |

| COVID-19 data at baseline | |||

| Time from symptom onset to baseline (days), median (IQR) (n = 262) | 7 (4–10) | 8 (5–11) | 6 (3–10) |

| Confusion on eligibility date, n (%) (n = 261) | 92 (35.2) | 35 (35.7) | 57 (35.0) |

| Dehydration on eligibility date, n (%) (n = 264) | 84 (31.8) | 27 (27.8) | 57 (34.1) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min), median (IQR) (n = 211) | 26 (22–31) | 28 (24–32) | 26 (22–30) |

| Oxygen flow at admission (L/min), median (IQR) (n = 261) | 4 (3–7) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–7.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), median (IQR) (n = 256) | 134 (119–150) | 132 (120–150) | 134 (116–150) |

| Neutrophil count (count/mm3), median (IQR) (n = 257) | 5400 (3810–8020) | 5220 (3800–7600) | 5575 (3832–8478) |

| Lymphocytes count (count/mm3), median (IQR) (n = 258) | 740 (502–1080) | 680 (480–1080) | 790 (520–1080) |

| Platelet count (count × 1000/mm3), median (IQR) (n = 260) | 204 (156–254) | 211 (164–256) | 199 (152–253) |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) > 40 mg/L, median (IQR) (n = 261) | 105 (69–169) | 114 (69–171) | 104 (68–164) |

| Percentage of lung affected >50% on the CT scan (n = 168b) | 37 (13.9) | 18 (18.3) | 19 (11.2) |

| Decision to limit and stop active treatments (at baseline) | 195 (73.0) | 79 (80.6) | 116 (68.7) |

| Corticosteroid treatment data | |||

| Corticosteroid, n (%) | |||

| Dexamethasone | 15 (5.6) | 15 (15.3) | |

| Methylprednisolone | 51 (19.1) | 51 (52.0) | |

| Prednisolone | 4 (1.5) | 4 (4.1) | |

| Prednisone | 22 (8.2) | 22 (22.4) | |

| Hydrocortisone | 3 (1.1) | 3 (3.1) | — |

| High-dose corticosteroid (≥120 mg/day) [16] | 28 (10.5) | 28 (28.6) | — |

| Corticosteroid treatment duration (days), median (IQR) (n = 94) | 5 (3–11) | 5 (3–11) | — |

| Corticosteroid dose (mg/kg/day eq. prednisone), median (IQR) | 1.1 (0.9–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.6) | |

Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; IQR, interquartile range .

The numbers in parentheses in the first column correspond to the quantity of data available before the imputation of missing baseline data by using multiple imputations with chained equations. Results are presented as % (count) unless stated otherwise.

This corresponds to 95 patients receiving corticosteroids with at least 0.4 mg/kg in the 72 h after baseline plus one patient from the control group randomly assigned to the treatment group to account for immortal time bias (see the detailed methods in the Supplementary Appendix S3).

Seventy-seven patients did not have a CT scan at admission.

Follow up and outcomes

Vital status was missing at day 14 for three of the 267 patients included in the main analysis (who had, however, been discharged in good health status before this date). During follow up, seven patients were transferred to ICU, one was intubated and 127 died before day 14.

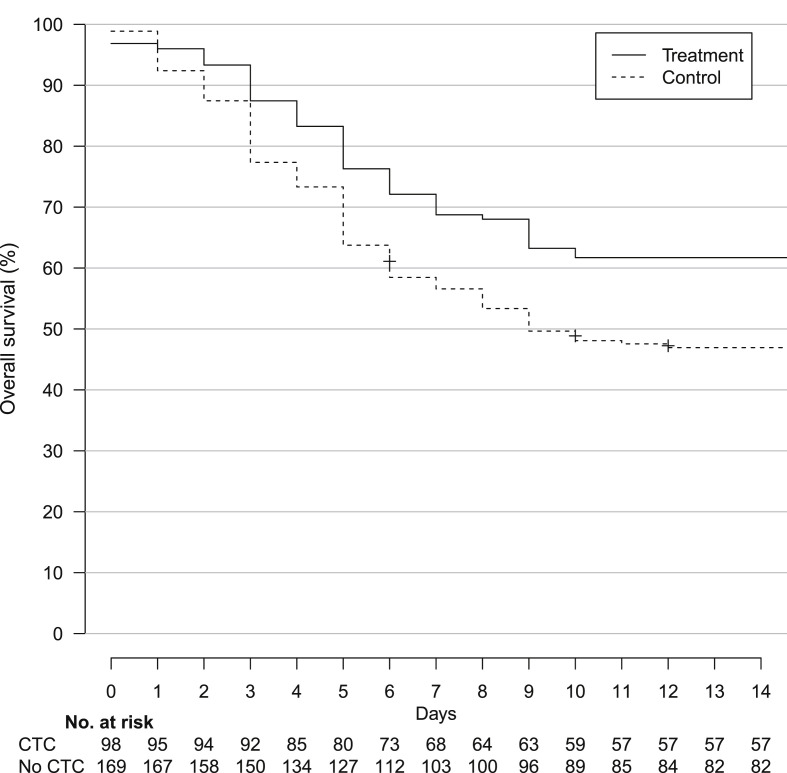

In total, 43/98 (43.9%) patients in the treatment group and 84/166 (50.6%) in the control group died before day 14 (hazard ratio 0.81, 95% CI 0.56–1.16). After balancing the baseline covariates by IPTW, survival was significantly higher for patients from the treatment group compared with the control group (weighted hazard ratio 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.99) (Fig. 1 ). There was no significant difference between the treatment and control groups for the proportion of patients discharged to home/rehabilitation at day 14 (weighted relative risk 1.12, 95% CI 0.68–1.82) or weaned from oxygen by that date (weighted relative risk 1.00, 95% CI 0.68–1.48). Sensitivity analyses are available in the Supplementary material (Tables S3–S5, Fig. S4).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for survival in the inverse probability of treatment sample. Abbreviation: CTC, corticosteroid treatment.

Among the 131 patients receiving corticosteroids, 22 (16.8%) developed adverse events but only 11/172 (6.4%) from the control group did. Frequent adverse events included hyperglycaemia (6.1% versus 0.6%), heart failure (2.3% versus 0.6%), confusion (3.0% versus 1.2%) and infection (1.5% versus 0%) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Adverse events

| Adverse event | Treatment group (n = 131), n (%) | Control group (n = 172), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Any | 22 (16.8) | 11 (6.4) |

| Expected with corticosteroids | ||

| Infection | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Hyperglycaemia | 8 (6.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Hypertension | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Confusion or psychiatric manifestation | 4 (3.1) | 2 (1.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Hypokalaemia or fluid overload | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Heart failure | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Other severe adverse events | ||

| Thromboembolic event | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Increased serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.2) |

| Renal failure | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

Adverse events are counted in the safety population, without weighting.

Discussion

In this emulated trial, corticosteroids significantly improved the 14-day survival of patients aged 80 years or older and hospitalized in a non-ICU department for severe COVID-19 with reassuring data regarding harms. Indeed, despite patients treated with corticosteroids experienced more adverse events than those treated with the standard of care, those effects remained rare and we found no major cardiotoxicity or neurotoxicity. Our study did not show a reduction in hospitalization length, but the end point at day 14 might have been too early to identify this. Such an effect would be important in reducing the geriatric complications of longer hospitalizations, such as functional decline, decreased nutrition and cognitive impairment [13].

Recommendations to treat older patients with corticosteroids have been based on results from studies performed in ICU [2] and on results from the RECOVERY trial, which showed an overall effect of dexamethasone, but a non-significant difference in the population of patients aged 80 years or more. The discrepancy with our findings may be explained by the fact that our study population was more homogeneous and more severely ill than that studied in the RECOVERY trial (35% of the patients older than 80 years in the RECOVERY trial were not under oxygen at randomization). Indeed, both the RECOVERY trial and the COCORICO study have shown that the more severely ill the patients, the more effective are the corticosteroids [1,5].

Our study has several limitations. Despite the use of robust methods to draw causal inferences, the study remains observational and potential unmeasured confounders may bias the results [14]. Second, the corticosteroid prescriptions were heterogeneous in terms of drugs, time of start, dose, and duration. Third, we could not account for the duration of corticosteroid prescriptions. For example, we may have observed only 3 days of corticosteroid treatment for a given patient because an event occurred on the fourth day. Fourth, our study population might not be representative of the population of older adults hospitalized during the first wave in France because it was recruited in centres involved in a network coordinated by REACTing (INSERM), which involved mainly non-geriatric wards. Fifth, our study was limited to the number of eligible patients available at the time of analysis. In particular, we found discrepant results between the main analysis and the sensitivity analyses. This may suggest that survivor bias is not completely accounted for in the main analysis or that our study lacked power. Finally, the follow up was limited to 14 days. Nonetheless, evidence shows that at the time of the study most deaths occurred before this cut-off point [10].

In all, our findings support the use of corticosteroids for patients aged 80 years or older with severe COVID-19. However, further research is needed to determine the right timing and dose of the treatment as well as the right indication, especially to clarify the benefit–risk balance. In particular, it would be interesting to assess whether its use in nursing homes could reduce the transfer of older adults with severe disease to the hospital. Strengthening the therapeutic arsenal for the care of older adults is critical as these patients are the most vulnerable to COVID-19 and may not fully benefit from vaccination because of the immunosenescence associated with advanced age [15].

Transparency declaration

LG, EP, NV, FB and EF have nothing to disclose. VTT is a minority shareholder from SKEZI, this activity is outside the submitted work. MM received research funds from GSK, outside the submitted work and personal fees for lectures from LFB and Amgen, outside the submitted work. FXL received personal fees for lectures from Gilead Sciences, bioMérieux and MSD outside the submitted work.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Author contributions

Concept and design were by FXL, LG and VTT. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data was performed by all authors from the COCO_OLD Study Group. VTT, FXL, EF, LG, FB, NV and MM drafted the manuscript and all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. VTT and EP performed the statistical analysis; administrative, technical and material support were by FXL, LG, VTT and EF. FXL supervised the study. VTT and EP had full access to all the data of the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Editor: L. Scudeller

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.03.021.

Contributor Information

COCO-OLD (Collaborative cOhort COrticoteroids for OLD patients with COvid-19) study Group:

Laure Gallay, Viet-Thi Tran, Elodie Perrodeau, Emmanuel Forestier, Matthieu Mahevas, Francesca Bisio, Nicolas Vignier, François-Xavier Lescure, Viet-Thi Tran, Elodie Perrodeau, Thibaut Fraisse, Diane Sanderink, Bertrand Lioger, Camille Boutrou, Anne - Laure Destrem, Pascal Gicquel, Martin Martinot, Jérémie Pasquier, Jean Reuter, Helene Desmurs-Clavel, Nicolas Benech, Boris Bienvenu, Nicolas Vignier, Guillemette Frémont, François Goehringer, Guillaume Chapelet, Olivier Grossi, Didier Laureillard, Cyrille Gourjault, Alexandre Lahens, François-Xavier Lescure, Célia Azoulay, Nicolas Carlier, Gianpiero Tebano, Jérôme Pacanowski, Simone Tunesi, Nadège Lemaire, Laurent Bellec, Firouze Bani-Sadr, Marie Pichenot, Kevin Alexandre, Laurie Masse, Olivier Robineau, Camille Thorey, Sophie Deriaz, Julien Saison, Marie Gousseff, Laura Goehrs, Fanny Pommeret, and Francesca Bisio

Appendix S1. COCO-OLD (Collaborative cOhort COrticoteroids for OLD patients with COvid-19) study Group

Writing committee

Laure Gallay, Viet-Thi Tran, Elodie Perrodeau, Emmanuel Forestier, Matthieu Mahevas, Francesca Bisio, Nicolas Vignier, François-Xavier Lescure (Principal Investigator and corresponding author).

Methodology and statistics

Centre d’Epidémiologie Clinique, Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris AP-HP/Université de Paris, Centre de Recherche Epidémiologie et Statistiques (CRESS UMR 1153): Viet-Thi Tran, Elodie Perrodeau.

Centres (alphabetically)

Ales, centre hospitalier, Service de médecine interne: Thibaut Fraisse.

Angers, centre hospitalo-universitaire, Service de Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales: Diane Sanderink.

Blois, centre hospitalier, Service de médecine interne et Maladies infectieuses: Bertrand Lioger.

Cayenne, centre hospitalier, Service Maladies infectieuses et tropicales: Camille Boutrou.

Chambéry, Centre hospitalier métropole Savoie, Service Maladies infectieuses et tropicales: Anne - Laure Destrem.

Chateaubriant, centre hospitalier, Service médecine polyvalente et gériatrie aigue: Pascal Gicquel.

Colmar, hôpital Louis Pasteur, Service de maladies infectieuses et tropicales: Martin Martinot.

Fort de France, centre hospitalo-universitaire Martinique, Service des maladies infectieuses et tropicales: Jérémie Pasquier.

Luxembourg (Luxembourg), centre hospitalier, service de réanimation polyvalente: Jean Reuter.

Lyon Hospices civils de Lyon, hôpital Edouard Herriot, médecine interne: Helene Desmurs-Clavel.

Lyon, Hospices civils de Lyon, hôpital de la Croix Rousse, Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales: Nicolas Benech.

Marseille, hôpital St Joseph, Service de Médecine Interne: Boris Bienvenu.

Melun, Centre hospitalier, Service Maladies infectieuses et tropicales: Nicolas Vignier.

Montreuil, centre hospitalier intercommunal André Grégoire, Service de médecine interne et Maladies infectieuses: Guillemette Frémont.

Nancy, centre hospitalo-universitaire, hôpital Brabois, Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales: François Goehringer.

Nantes, centre hospitalo-universitaire, service de Médecine Aiguë Gériatrique: Guillaume Chapelet.

Nantes, Hôpital privé du confluent de Nantes, Service de Médecine Interne et Maladies Infectieuses: Olivier Grossi.

Nîmes, centre hospitalo-universitaire Carémeau, Service des maladies infectieuses et tropicales: Didier Laureillard.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital Bichat: Cyrille Gourjault, Alexandre Lahens, François-Xavier Lescure.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital Cochin, Service de Médecine interne: Célia Azoulay.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital Cochin, Service de pneumologie: Nicolas Carlier.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Service des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales: Gianpiero Tebano.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital St Antoine: Jérôme Pacanowski.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital Jean Verdier: Simone Tunesi.

Paris, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), Hôpital Tenon: Nadège Lemaire.

Pontivy, centre hospitalier centre Bretagne, Service de Médecine Polyvalente, Maladies Infectieuses, Dermatologie: Laurent Bellec.

Reims, centre hospitalo-universitaire, service de Médecine interne, Immunologie clinique et maladies infectieuses: Firouze Bani-Sadr.

Roubaix, centre hospitalier, Service de Médecine interne: Marie Pichenot.

Rouen, centre hospitalo-universitaire, Service des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales: Kevin Alexandre.

Saint Denis (réunion), centre hospitalo-universitaire, service de pneumologie: Laurie Masse.

Tourcoing, centre hospitalier, hôpital Guy Chatiliez, Service Universitaire des Maladies Infectieuses et du Voyageur: Olivier Robineau.

Tours, centre hospitalo-universitaire, Pôle Médecine: Camille Thorey, Sophie Deriaz.

Valence, centre hospitalier, Service de maladie infectieuse: Julien Saison.

Vannes, Centre Hospitalier Bretagne Atlantique, Service de médecine interne, maladies infectieuses et hématologie: Marie Gousseff.

Versaille, centre hospitalier, Service médecine polyvalente et gériatrie aigue: Laura Goehrs.

Villejuif, Institut Gustave Roussy, Département Interdisciplinaire d’Organisation des Parcours Patients: Fanny Pommeret.

Vierzon, centre hospitalier, Service de maladie infectieuse: Francesca Bisio.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., Mafham M., Bell J.L., Linsell L. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;25:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S., Villar J., Angus D.C. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus D.C., Derde L., Al-Beidh F., Annane D., Arabi Y., Beane A. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 Corticosteroid Domain Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1317–1329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomazini B.M., Maia I.S., Cavalcanti A.B., Berwanger O., Rosa R.G., Veiga V.C. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19: the CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran V.-T., Mahévas M., Bani-Sadr F., Robineau O., Perpoint O., Perrodeau E. Corticosteroids in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartoletti M., Marconi L., Scudeller L., Pancaldi L., Tedeschi S., Giannella M. Efficacy of corticosteroid treatment for hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19: a multicenter study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahid Z., Kalayanamitra R., McClafferty B., Kepko D., Ramgobin D., Patel R. COVID-19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:926–929. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique . Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique; Paris: 2020. Utilisation de la dexaméthasone et d’autres corticoïdes dans le Covid-19, Avis et Rapports. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng Z., Yu H., Chen H., Qi W., Chen L., Chen G. Longitudinal changes of inflammatory parameters and their correlation with disease severity and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 from Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24:525. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salje H., Tran Kiem C., Lefrancq N., Courtejoie N., Bosetti P., Paireau J. Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. Science. 2020;369:208–211. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernán M.A., Sauer B.C., Hernández-Díaz S., Platt R., Shrier I. Specifying a target trial prevents immortal time bias and other self-inflicted injuries in observational analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee T.C., MacKenzie L.J., McDonald E.G., Tong S.Y.C. An observational cohort study of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for COVID-19: (Can’t Get No) Satisfaction. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:216–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.High K.P., Bradley S., Loeb M., Palmer R., Quagliarello V., Yoshikawa T. A new paradigm for clinical investigation of infectious syndromes in older adults: assessment of functional status as a risk factor and outcome measure. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:114–122. doi: 10.1086/426082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernán M.A. The C-word: scientific euphemisms do not improve causal inference from observational data. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:616–619. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helfand B.K.I., Webb M., Gartaganis S.L., Fuller L., Kwon C.S., Inouye S.K. The exclusion of older persons from vaccine and treatment trials for coronavirus disease 2019—missing the target. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1546–1549. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buttgereit F., da Silva J.A., Boers M., Burmester G.R., Cutolo M., Jacobs J. Standardised nomenclature for glucocorticoid dosages and glucocorticoid treatment regimens: current questions and tentative answers in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:718–722. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.8.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.