Abstract

This study evaluated the efficacy of Momordica charantia (MC; bitter melon) extracts against andropause symptoms. We fermented MC with Lactobacillus plantarum and verified the ability of the fermented MC extracts (FMEs) to control testosterone deficiency by using aging male rats as an animal model of andropause. FME administration considerably increased total and free testosterone levels, muscle mass, forced swimming time, and total and motile sperm counts in aging male rats. In contrast, sex hormone-binding globulin, retroperitoneal fat, serum cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were significantly reduced in the treated groups compared to the non-treated control aging male rats. Furthermore, we observed that FME enhanced the expression of testosterone biosynthesis-related genes but reduced the expression of testosterone degradation-related genes in a mouse Leydig cell line. These results suggest that FME has effective pharmacological activities that increase and restore free testosterone levels and that FME may be employed as a promising natural product for alleviating testosterone deficiency syndrome.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-020-00872-x.

Keywords: Andropause, Male climacteric syndrome, Momordica charantia, Testosterone deficiency, Lactic acid bacteria, Fermentation

Introduction

Climacterium is commonly experienced by both men and women (Horstman et al., 2012). Generally, climacterium has been recognized as a symptom of middle-aged women caused by a decrease in female hormones, but men also exhibit similar symptoms caused by a decrease in male hormones and testosterone, although these symptoms are not as evident as those in women’s climacterium (Horstman et al., 2012). Most middle-aged and older men are not aware of the seriousness of climacteric symptoms and consider them only as signs and pain from stress, only to experience a sudden decline in physical functions and accelerated aging (Cunningham, 2013). Male climacterium or andropause is thus referred to as testosterone deficiency syndrome caused by the functional degeneration of the endocrine system based on male hormones (Hassan and Barkin, 2016). Andropause is accompanied by physical symptoms, such as fatigue, erectile dysfunction, muscle weakness, body fat increase, and osteoporosis, and psychological changes, such as hyposexuality, decreased sense of well-being, depression, concentration and memory decline, and sleep disturbances (Davidiuk and Broderick, 2016). Testosterone replacement therapy normally results in improvements in these symptoms. However, extra care should be taken during treatment if a professional diagnosis is required and if any prostatic disorder is present (Cunningham, 2013). Various side effects, such as the fluid accumulation in the body, polycythemia, sleep apnea deterioration and gynecomastia, may also occur (Ismaeel and Wang, 2017). Therefore, it is urgent to develop a therapy that can improve the symptoms without any of these side effects. Efforts are thus needed to use safer, natural extracts to relieve and improve the symptoms of andropause and minimize the risks of testosterone replacement therapy.

Momordica charantia (MC), which is also called bitter melon, is an annual climbing plant that belongs to the Cucurbitaceae family. This plant has been commonly used as both food and medicine in tropical and subtropical regions (Gao et al., 2019). It is well known that the fruit of MC contains numerous bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, polyphenols, saponins, alkaloids, glucosides, β-carotene, pectin, and lignin, while immature bitter melon is rich in iron and vitamins C and A. These components have been reported to promote insulin secretion and reduce blood sugar, as well as exhibit numerous other pharmacological activities (Jia et al., 2017). However, no research has yet been conducted to evaluate the activities of MC on male climacterium. Thus, in this study, the effects of M. charantia extracts (MEs) on relieving andropause symptoms were investigated. Because numerous studies have been performed using lactic acid bacterial fermentation to increase the functional activities of natural extracts (Gao et al., 2019; Park et al., 2015), we attempted to ferment the fruit of MC with Lactobacillus plantarum, which is the microorganism generally used for the fermentation of fruits and vegetables, furthermore, we eluted hot water extracts and then administered the extracts to aging male rats to verify the functional activities of these fermented extracts compared with those of the nonfermented extracts. The mechanism of action was also investigated at the cellular level using a mouse Leydig cell line. Here, we report promising results, which are previously unrevealed effects of fermented M. charantia extracts (FMEs) on relieving andropause symptoms.

Materials and methods

Preparation of FMEs

The bitter melon used for this study was harvested and dried at Hwasoon, Jeonnam, located in the southern province of South Korea. The normal nonfermented ME was prepared from 100 g of the dried flesh of bitter melon with one liter of water by heating it to 70–85 °C on a heating mantle for 24 h. The extract was filtered, vacuum evaporated, and freeze dried to obtain the extract powders. To prepare the FME, approximately 1 × 109 cells of L. plantarum (KCTC 3108) were added to 100 g of the dried flesh and mixed with one liter of water. This mixture was incubated in a 30 °C shaking incubator for 96 h for lactic acid bacterial fermentation (Park et al., 2015). After fermentation, the same process that was used to make the ME was applied to prepare the FME. The extract powders were stored at − 20 °C and mixed in drinking water for use.

Determination of total polyphenol and flavonoid content in ME and FME

Total phenolic phytochemicals were assayed using the Folin-Denis method (Gutfinger, 1981). Briefly, 1 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 10% Na2CO3 solution were sequentially added to 1 mL of appropriately diluted extracts and then allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 h; then, the absorbance at 700 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (EMC-11D-V; EmcLab, Duisburg, Germany). The total polyphenol content in the MEs was calculated using a standard calibration curve obtained by analyzing gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). The total flavonoid content was determined using the aluminum nitrate method (Moreno et al., 2000). Briefly, 0.1 mL of 10% aluminum nitrate, 0.1 mL of 1 M aqueous potassium acetate and 4.3 mL of 80% ethanol were added to 0.5 mL of appropriately diluted extracts. After the mixtures were allowed to stand at room temperature for 40 min, the absorbance at 415 nm was determined spectrophotometrically. The total flavonoid content of the MEs was calculated using quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) as a standard.

Animals

For this study, 12-week-old male Sprague–Dawley rats were purchased from DBL (Eumseong, Chungbuk, Korea). All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed (JWCUC-201607-001-02). The animals were reared up to 50 weeks old with general solid feed purchased from DBL. In consideration of forced swimming affecting other biochemical indicators, 80 animals were divided into the forced swimming group and the blood, body fat, muscle and sperm count measurement group, with 40 animals in each group. The average weight of the rats was approximately 560 g, and 8 rats were temporarily classified into each experimental group. The rearing environment for rats was set to a temperature of 24 °C, a relative humidity of 50 ± 10%, a ventilation frequency of 10–20 times/h, and 12 h of light (lights on at 08:00, lights out at 20:00). Two rats were placed in each cage. The experimental groups were divided into ME and FME groups and were orally administered the treatments at a certain time daily for 6 weeks.

Blood serum extraction

Blood (400–500 μL) was taken from the tail vein of the experimental rats anesthetized with diethyl ether on the same day and at the same time every week. On the last day of the experiment, blood was taken directly from the heart to measure biochemical indicators other than testosterone. The sampled blood was quickly placed on ice and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Afterward, the separated blood serum was used for biochemical assays.

Measurement of blood testosterone levels

Blood was drawn on the same day and at the same time every week to measure the total blood testosterone content using a testosterone measurement kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Montgomery, PA, USA). Blood serum and standard diluent were added to the goat anti-mouse IgG microtiter plate. Then, testosterone antibody was mixed and incubated in the plate shaker at 500 rpm for 1 h and again for another 1 h in darkness at 37 °C with the substrate solution. Afterward, stop solution was added and mixed, and the absorbance was measured at a 405 nm wavelength. The concentration of free testosterone was measured using a free testosterone assay kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of blood sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG)

The blood SHBG content was measured using an SHBG assay kit (Cloud-Clone Corp, Houston, TX, USA). Blood serum samples and standard solution were added to a precoated microplate and sealed for incubation for 2 h at 37 °C. Afterward, the solution was removed, and detection reagent A was added and sealed for incubation for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, the sample was washed with wash buffer. After the solution was removed, detection reagent B was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing and removing the solution, substrate solution was added and incubated in darkness at 37 °C for 20 min. Stop solution was added, and the absorbance was immediately measured at a 450 nm wavelength using a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Measurement of blood prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

Blood PSA content was measured with a PSA assay kit (Cusabio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Plasma samples and standard solution were added to precoated microplates and reacted for 2 h at 37 °C. Afterward, the solution was removed, and a biotin-conjugated antibody was added and sealed for reaction for 2 h at 37 °C and then washed three times with wash buffer. Afterward, the solution was removed, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-avidin was added, and the wells were sealed for reaction for 30 min at 37 °C and then washed five times with wash buffer. Next, the solution was removed, and substrate solution was added for 20 min at 37 °C for reaction in darkness. Finally, stop solution was added, and the absorbance was measured immediately at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad).

Measurement of abdominal fat and muscles

Weight change was measured regularly at specific times during the experiment. The experimental rats were surgically opened, and cardiac blood was collected. To measure abdominal fat, retroperitoneal fat was removed and subsequently washed with saline solution. Then, moisture was removed with filter paper to measure the weight of damp-dried fat tissues. Muscle mass was measured by cutting the femoral section and separating the lateral muscles (vastus lateralis), which occupy a large proportion of the quadriceps muscles.

Blood lipid analysis

Blood lipid assay kits were purchased and used to measure the content of total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and triglycerides (TGs) (Asan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea).

Forced swimming analysis

A plastic water tank (W50 × D40 × H60, cm) was filled with sterilized water up to approximately 30 cm, and the water temperature was maintained at 24 ± 2 °C with an aquarium heater (EHEIM GmbH & Co., KG, Deizisau, Germany). Rats were deemed exhausted when their nose was submerged below the water level for more than 2 s five times, and the time to this exhaustion was measured to confirm exhaustive swimming. The experiment was conducted with eight animals in each group.

Determination of sperm count and motility

The epididymis on the left and right sides of the experimental rats were extracted, chopped with surgical scissors, and cultivated for 10 min in 4 mL of M199 medium containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin, which was preheated to 37 °C, and then sperm were collected. The collected sperm were first diluted in 32 °C M199 medium to make the environment similar to that of the interior of the body and thus to improve the survival rate. One hundred microliters of the first dilution was added to 900 µL of M199 medium to make the second dilution. The sperm count was then performed using a hemocytometer by applying 10 µL of the second dilution. Sperm motility was calculated by measuring the percentage of active sperm.

Cell culture

The TM3 cell line was purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). TM3 mouse Leydig cells, which are derived from the testes of immature BALB/c mice and retain many of their in vivo functions, are nontumorigenic testicular cells that were originally characterized based on their morphology, hormone responsiveness, and steroid metabolism (Mather, 1980). For this reason, TM3 cells have been extensively used in many studies to analyze how aging and environmental factors are related to testosterone production (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, by using TM3 Leydig cells, we analyzed whether ME and FME could regulate the expression of genes related to testosterone synthesis and degradation. A total of 1 × 106 TM3 cells were seeded into DMEM/F-12 medium (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% FBS in 60 mm cell culture dishes (SPL Life Science, Pocheon, Gyeonggi, Korea) and cultivated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. After 24 h, the medium was discarded, and the cells were washed once with PBS. Fresh medium containing the proper concentration of ME or FME was added to each of the cell culture dishes and incubated for an additional 48 h.

Analysis of marker gene expression using real-time qPCR

To compare the differences between the relative gene expression levels involved in testosterone biosynthesis, RNA was then extracted from the cells using Trizol Reagent (Gibco-BRL). cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA with a ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and was assayed with real-time PCR (Exicycler96 real-time quantitative thermal block) (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The primer sequences used for real-time qPCR were as follows: for 17,20-lyase, forward 5′-CCTGCTGGAAGGTGTAGCTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCTGCTGGAAGGTGTAGCTC-3′; for 17β-HSD3, forward 5′-GTTCTCGCAGCACCTTTTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CAGCTTCCAGTGGTCCTCTC-3′; for aromatase, forward 5′-ACAATAAGATGTATGGAGAGTTCA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTTGAGGACTTGCTGATAA-3′; and for 5α-reductase, forward 5′-GCAAGCCTATTACCTGGTT-3′ and reverse 5′-AGAAGACACCGACGCTAA-3′. For GAPDH as an internal control, forward 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′ and reverse 5′-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3′ were used.

Statistical analysis

All analytical data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE) or mean ± standard deviation (SD) (Table 1), and the test results were analyzed with the GraphPad Prism 5.0 program (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Intergroup comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test. Probability values (p) < 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1.

Total polyphenol and flavonoid contents in Momordica charantia extract (ME) and fermented M. charantia extract (FME)

| Samples | Total polyphenol (GAE, mg/g)1 | Total flavonoid (QE, mg/g)1 |

|---|---|---|

| ME | 24.9 ± 0.96a | 18.79 ± 0.77a |

| FME | 43.35 ± 0.85b | 29.75 ± 0.57b |

Values are the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Values with different letters are significantly different at the level of 0.05

1GAE and QE represent gallic acid equivalent and quercetin equivalent, respectively

Results and discussion

Total polyphenol and flavonoid content in ME and FME

Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites commonly found in many plants and are known to exhibit various physiological activities (Nazarni et al., 2016; Ryu et al., 2019). The effectiveness of polyphenols may not reach its maximum because the bioavailability and bioefficacy of these compounds might be hindered by strong binding to the cellulose matrix in plants (Ryu et al., 2019). Since the fermentation of lactic acid bacteria can change the content of physiologically active components in MC and increase useful physiological activity, the total polyphenol and flavonoid contents of ME and FME were compared. After fermentation, the total polyphenol and flavonoid contents were increased approximately 1.7 and 1.6 times, respectively, in FME compared to those in ME (Table 1). From this result, we assumed that fermentation with lactic acid bacteria may have had a physical effect on the bitter melon tissues, allowing physiologically active components to be more readily eluted.

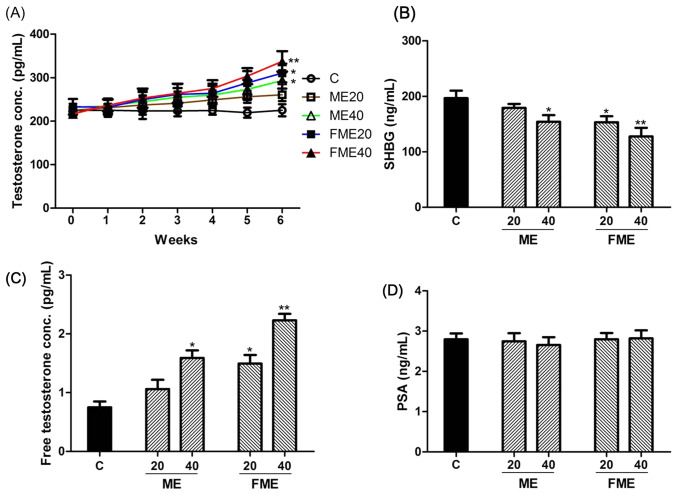

Improvement in total blood testosterone levels

First, the validity of the testosterone deficiency model used in this study was verified by confirming testosterone levels in young (12-week-old) and aged (50-week-old) male rats. Generally, blood testosterone levels in male rats vary with sexual experience, strain and time of day (Low et al., 2020). In our experiment, the blood testosterone concentration of young rats was 1.86 ± 0.32 ng/mL, which was consistent with the ranges reported in a previous study (Low et al., 2020). The concentration of testosterone in 50-week-old rats was 224.50 ± 13.44 pg/mL, which was dramatically decreased to approximately 12% of that of young rats. These results indicated that the aged rats used in this experiment were a suitable model of testosterone deficiency. Next, the effects of ME and FME on testosterone secretion in vivo were investigated by administrating these extracts to aged rats daily for 6 weeks (Fig. 1A). Before oral administration (0 weeks), the concentration of testosterone in blood was mostly similar between the control (no administration group) and experimental groups, at 216.45 ± 15.36–233.14 ± 23.17 pg/mL. After approximately 4 weeks of administration, the experimental groups showed a tendency toward increased blood testosterone levels. However, the control group showed similar levels of testosterone even after 6 weeks (225.23 ± 18.21 pg/mL), which indicated that the testosterone levels were steadily maintained in these aging rats without any treatment. Nevertheless, the experimental groups showed gradual increases in testosterone levels (Fig. 1A). The ME20 and ME40 groups exhibited 260.57 ± 21.25 pg/mL and 293.61 ± 16.74 pg/mL, respectively, which meant that the testosterone levels increased approximately 16% and 30%, respectively, compared to that in the control group for 6 weeks. The FME20 and FME40 groups showed dramatic increases in testosterone levels (up to 310.70 ± 17.58 pg/mL and 337.64 ± 14.62 pg/mL, respectively), which indicated that the testosterone levels increased almost 38% and 50%, respectively, compared to those in the control group, and these increases were statistically significant. From these results, we concluded that the administration of ME and FME could enhance the testosterone production capacity in aging rats and that andropause symptoms caused by a deficiency in testosterone might thus be relieved by administration of these extracts.

Fig. 1.

Analyses of total and free testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels in blood serum after 6 weeks of Momordica charantia extract (ME) administration. (A) Total serum testosterone levels were significantly increased in the ME40, FME20 and FME40 groups compared to those in the control group. (B) Serum SHBG levels were significantly decreased in the ME40, FME20 and FME40 groups. (C) Free serum testosterone levels were significantly increased in the ME40, FME20 and FME40 groups. (D) No difference in serum PSA levels was observed between the control and ME-administered groups. C, water-administered control; ME20 and ME40: normal ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively); FME20 and FME40: fermented ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

MC contains various bioactive components, on which no study has been conducted directly in relation to male hormones. Some of the MC components may be linked to male sexual functions because pectin was effective in decreasing oxidative stress and toxicity of the testes caused by cadmium, while lignin was effective in improving benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (Bisson et al., 2014; Koriem et al., 2013). In addition, saponin was reported to increase the blood testosterone concentration (Salvati et al., 1996). The main phenolic constituents in MEs are catechin, gallic acid, gentisic acid, chlorogenic acid and epicatechin (Shahidi and Ambigaipalan, 2015). Catechins (catechin and epicatechin) were reported to increase the plasma testosterone level in vivo in male rats by acting directly on rat Leydig cells through increasing the effect of cAMP (Yu et al., 2010). In particular, epicatechin was found to increase testosterone secretion by increasing the enzyme activity of 17β-HSD in Leydig cells (Yu et al., 2010). Moreover, it was reported that gallic acid might have protective effects on the testes under stress conditions, such as electromagnetic radiation (EMR) exposure, which can induce testicular damage (Saygin et al., 2016). The study found that the testosterone level decreased in the EMR-treated group but increased and recovered to the level of the control group when the EMR-treated group was supplied gallic acid. In addition, oral administration of chlorogenic acid in mice can significantly inhibit the BPH progression (Huang et al., 2017). The preventive effect on BPH was likely due to inhibition of 5α-reductase activity by chlorogenic acid. These published reports indicated that the phenolic compounds in extracts of MC have functional activities to improve testosterone deficiency by modulating the expression of genes related to testosterone biosynthesis and degradation. Considering these findings and preceding studies, the bioactive components of MC could be expected to increase blood testosterone. Additionally, compared to ME, FME showed significant positive effects on increasing testosterone levels, which suggests that fermentation might increase the content and bioavailability of various bioactive components other than the ones mentioned above. A study on the antidiabetic effect of MEs showed enhanced activities of extracts fermented with lactic acid bacteria over those of nonfermented extracts (Park et al., 2015). Although chromatographic analysis of diosgenin, which is a plant-derived steroid structurally similar to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), showed similar patterns in ME and FME in this experimental condition, the bioefficacy of diosgenin in fermented extracts or other biologically active phytochemicals readily released by fermentation may have synergistic effects on improving testosterone levels (Ryu et al., 2019; Sato et al., 2014) (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 1). Therefore, further studies may be needed to identify the crucial components of MEs affecting the testosterone levels and to investigate the effects of lactic acid bacterial fermentation.

Changes in blood SHBG and free testosterone levels

SHBG, which is generated from the liver, regulates the bioactivity of testosterone (Ring et al., 2017). Approximately 60–80% of testosterone binds to SHBG strongly and becomes a high molecular weight complex, which cannot cross the cell membrane and thus remains in a metabolically inactivated state in the body. Testosterone that is not combined with SHBG (free testosterone) actually functions as an active hormone (Ring et al., 2017). Therefore, the concentration of free testosterone, which is not combined with SHBG, is more important than the concentration of total testosterone with respect to testosterone deficiency (Shea et al., 2014). To investigate the effect of ME and FME administration on changes in SHBG levels, SHBG concentrations in blood serum were measured between the control group and the experimental group, which received the extracts for 6 weeks (Fig. 1B). In comparison with the control group (196.4 ± 9.5 ng/mL), the SHBG level decreased by approximately 9% to 178.8 ± 6.1 ng/mL in the ME20 group, showing no significant difference, but it decreased by approximately 21% to 154.2 ± 8.6 ng/mL in the ME40 group. FME decreased the SHBG level by approximately 22% to 153.3 ± 7.2 ng/mL in the FME20 group and by approximately 35% to 127.5 ± 10.3 ng/mL in the FME40 group. In summary, at the same dosage, FME administration showed a stronger effect than ME on the reduction in SHBG levels and was deemed to retain a level of bioactive free testosterone that was higher than that in the control group. Therefore, we directly measured the concentration of free testosterone in blood serum as an expression of bioactivity after 6 weeks of administration. The free testosterone level of the control group was 0.75 ± 0.11 pg/mL, while the levels in the experimental groups were 1.06 ± 0.21 pg/mL, 1.59 ± 0.18 pg/mL, 1.50 ± 0.17 pg/mL and 2.23 ± 0.13 pg/mL with the ME20, ME40, FME20 and FME40 treatments, respectively (Fig. 1C). These results indicated that the increase in free testosterone levels depended on the concentration as well as on the fermentation of MEs. These results also suggested that the decreased SHBG levels were responsible for the augmentation of free active testosterone levels in the experimental groups. The accurate mechanism of MEs decreasing SHBG concentrations has not yet been studied, and thus, further research on this topic may be needed.

Differences in blood PSA levels

As some studies have reported that testosterone replacement therapy may induce prostatic cancer that has already occurred to progress or deteriorate, screening tests and follow-up studies must be conducted on prostatic cancer through blood tests, such as a prostate checkup or PSA analysis, before and after male hormone replacement therapy (Morgentaler et al., 2014). Therefore, we measured the changes in blood PSA concentrations after 6 weeks of ME and FME administration to verify any negative effect on the prostate that may occur in testosterone replacement therapy (Fig. 1D). The results showed no significant difference in PSA levels between the control and experimental groups. Thus, it appears that ME or FME administration does not cause side effects of PSA elevation in the prostate that may occur with testosterone replacement therapy.

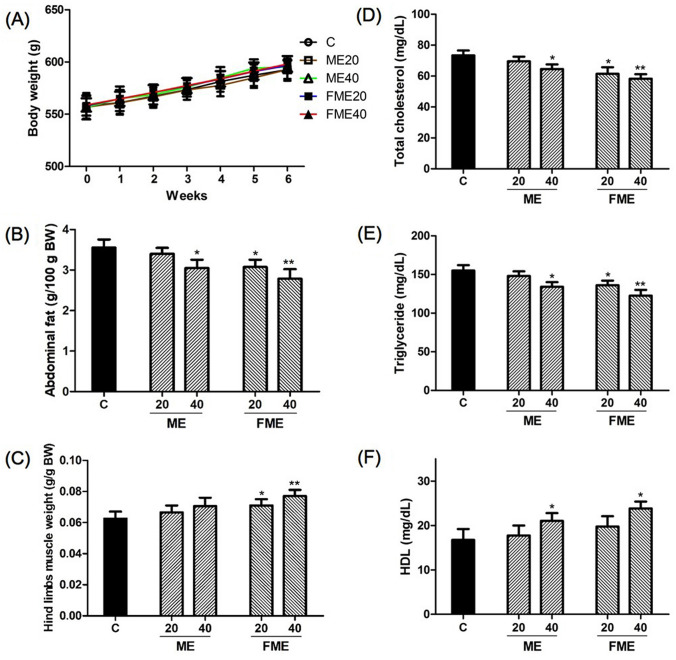

Improvements in body fat and muscle mass

Some of the major symptoms of andropause caused by male hormone deficiency are an increase in body fat and a decrease in muscle mass, which lead to muscular weakness and fatigue (Corona et al., 2016). Therefore, we examined the effects of ME and FME administration by measuring abdominal fat and the thigh muscles. No significant difference in body weight was noted between the groups after 6 weeks of ME or FME administration (Fig. 2A). The abdominal fat weight per 100 g body weight was 3.56 ± 0.18 g in the control group and decreased to 3.40 ± 0.13 g and 3.08 ± 0.17 g in the ME20 and FME20 groups, respectively (Fig. 2B). In particular, the FME20 group showed a significant difference from the control group. The fat weight decreased to 3.05 ± 0.23 g and 2.78 ± 0.25 g in the high-dose administration groups of ME40 and FME40, respectively, exhibiting statistically significant differences (Fig. 2B). The ratio of thigh muscle to body weight was 0.061 ± 0.006 in the control group and increased to 0.067 ± 0.006 and 0.070 ± 0.008 in the ME20 and ME40 groups, respectively, showing no statistically significant difference. In contrast, the group treated with the FME showed corresponding ratios of 0.071 ± 0.005 with FME20 and 0.077 ± 0.005 with FME40, which was a significant increase over that in the control group (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that ME and FME administration positively affected the decrease in body fat and increase in muscle mass. This effect of body fat decrease and muscle mass increase is thought to have been caused by various functional components of MEs. Gong et al. (2017) and Wang and Ryu (2015) reported the effects of MEs on antiobesity activity and reduction in abdominal fat, while Alam et al. (2015) reported the effects of MC on weight decrease and metabolic syndrome relief, which are generally consistent with our findings in this study. The direct correlation between the MEs and muscle mass increase has not yet been reported, but considering the findings of previous studies reporting that testosterone replacement increased the femoral muscle mass in aging men (Borst and Yarrow, 2015; Storer et al., 2017), the increase in testosterone content is thought to have originated from MC administration, which needs to be clarified by further investigation. In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that MEs may delay the increases in abdominal fat and decreases in muscle mass that are the general symptoms of andropause.

Fig. 2.

Effects of Momordica charantia extracts (ME) on body weight (A), abdominal fat (B), hind limbs muscle (C), total cholesterol (D), triglyceride (E), and HDL cholesterol (F) after 6 weeks of administration. C, water-administered control; ME20 and ME40: normal ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively); FME20 and FME40: fermented ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Improvement in blood lipid levels

Male hormone deficiency is known to be closely related to metabolic syndrome involving abdominal obesity and dyslipidemia (Anaissie et al., 2017). Previous studies have reported lipid disorders, such as a decrease in blood HDL cholesterol and an increase in total cholesterol and triglycerides when testosterone content is decreased, which subsequently increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (Sanchez et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2015). However, testosterone replacement therapy has been shown to improve markers of metabolic syndrome in men with hypogonadism (Haider et al., 2016). Therefore, we measured changes in total cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol to confirm whether dyslipidemia could be improved through treatment with MEs. In comparison with 73.4 ± 3.7 mg/dL in the control group, the levels of total blood cholesterol in the experimental groups showed an overall decrease. In particular, statistically significant decreases were shown in the FME20 and FME40 groups, reaching 61.5 ± 6.2 mg/dL and 58.3 ± 4.5 mg/dL, respectively (Fig. 2D). The levels of triglycerides also generally decreased in the experimental groups. In particular, the triglyceride levels of the ME40 and FME40 groups (134.4 ± 13.7 mg/dL and 122.5 ± 17.2 mg/dL, respectively) were significantly decreased by approximately 13% and 21% compared to 155.2 ± 15.3 mg/dL of the control group (Fig. 2E). The levels of HDL cholesterol were slightly increased to 17.8 ± 3.5 mg/dL and 19.7 ± 3.7 mg/dL in the ME20 and FME20 groups, respectively, compared with the control group level of 16.8 ± 3.8 mg/dL, but the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, a significant difference was noted in the high-concentration ME40 and FME40 groups, in which the HDL levels were increased to 21.1 ± 2.8 mg/dL and 23.9 ± 2.6 mg/dL (by approximately 19% and 34%), respectively, compared with those in the control group (Fig. 2F). The improvement in dyslipidemia in this experiment may be due to the increase in testosterone stimulated by active components present in MEs, which is in line with the results of Naz et al. (2016), who reported that the administration of MEs reduces the concentration of serum lipids in rats with hyperlipidemia, as well as the findings of Park et al. (2015), who showed a positive effect on lipid metabolism in diabetic mice. Therefore, administration of ME and FME is expected to have positive effects on disorders of blood lipid metabolism, which are commonly observed in andropause.

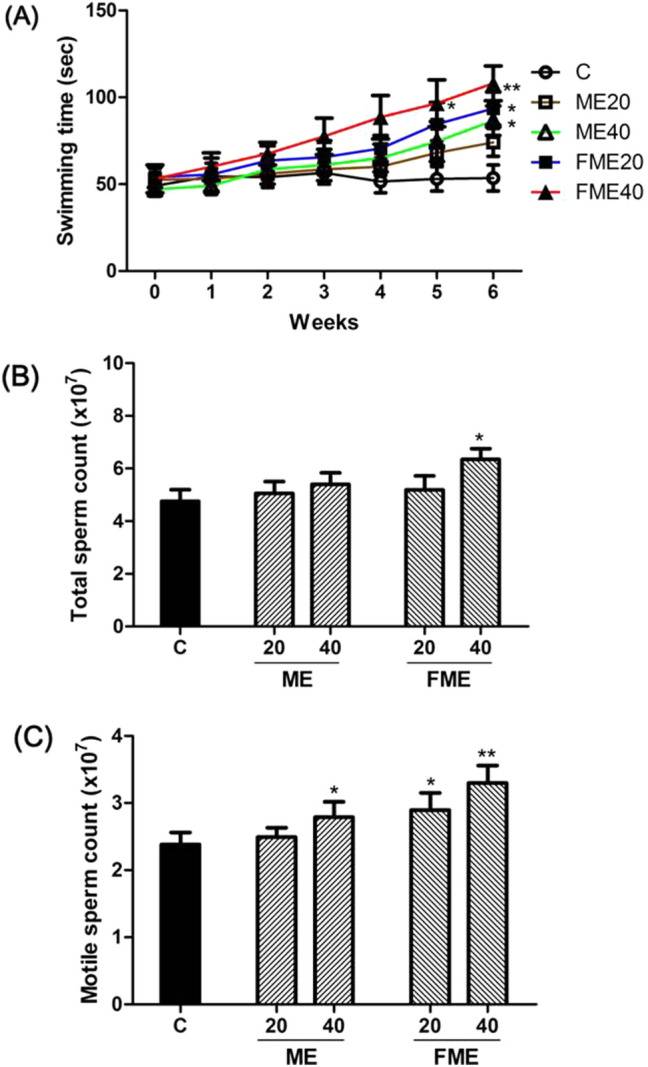

Improvements in exercise performance

Andropause is commonly accompanied by deterioration in muscle mass, strength, and vitality and increased fatigue (Hassan and Barkin, 2016). Therefore, in this experiment, the forced swimming ability was measured every week to determine how the increase in muscle mass affected the actual exercise performance according to ME and FME administration for 6 weeks (Fig. 3A). Differences between the control group and experimental group started to appear in week 4 and became definite in week 5. The maximum swimming time in week 6 was 54 ± 11 s in the control group and increased in the groups administered MC to 74 ± 11 s with ME20, 87 ± 12 s with ME40, 94 ± 13 s with FME20, and 109 ± 15 s with FME40. In summary, the ME40, FME20, and FME40 groups showed a significant difference in forced swimming time compared to the control group in week 6. These results indicated that MC administration improved the exercise performance of the experimental animals, suggesting a positive effect on decreasing fatigue and increasing vitality in men experiencing andropause. These findings suggest that testosterone content increased by MC administration improved exercise performance, which is in line with the results of Hsiao et al. (2017) and Kim et al. (2016), who reported that MEs decrease fatigue and improve endurance and exercise performance, as well as other studies that have reported the effect of testosterone in improving muscle mass and strength (Mouser et al., 2016) and the effect of testosterone replacement therapy on the improvement in male exercise performance (Hildreth et al., 2013).

Fig. 3.

Effects of Momordica charantia extracts (ME) on endurance capacity for swimming (A), total sperm count (B) and motile sperm count (C) after 6 weeks of administration. C, water-administered control; ME20 and ME40: normal ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively); FME20 and FME40: fermented ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Improvements in sperm count

Testosterone is an essential hormone for male reproductive functions, largely affecting spermatogenesis and sperm motility (Khourdaji et al., 2018). Based on the increase in testosterone content due to ME administration, the effects on sperm count and motility were investigated (Fig. 3B, C). The total sperm count was 4.75 × 107 in the control group and slightly increased in the experimental groups to 5.05 × 107 and 5.40 × 107 with ME20 and ME40, respectively, but this difference was not statistically significant. Among the FME groups, the total sperm count slightly increased to 5.19 × 107 with FME20 and particularly increased by approximately 33% to 6.33 × 107 with FME40, which was statistically significant (Fig. 3B). The motile sperm count increased to 2.49 × 107 and 2.90 × 107 in the ME20 and ME40 groups, respectively, in comparison with that in the control group (2.38 × 107). The sperm count significantly increased to 2.79 × 107 and 3.3 × 107 in the FME20 and FME40 groups, respectively (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrated that the MEs and the components present in the extracts could stimulate testosterone secretion and prevent SHBG production and that increased free active testosterone helped to improve spermatogenesis and subsequent motility in vivo.

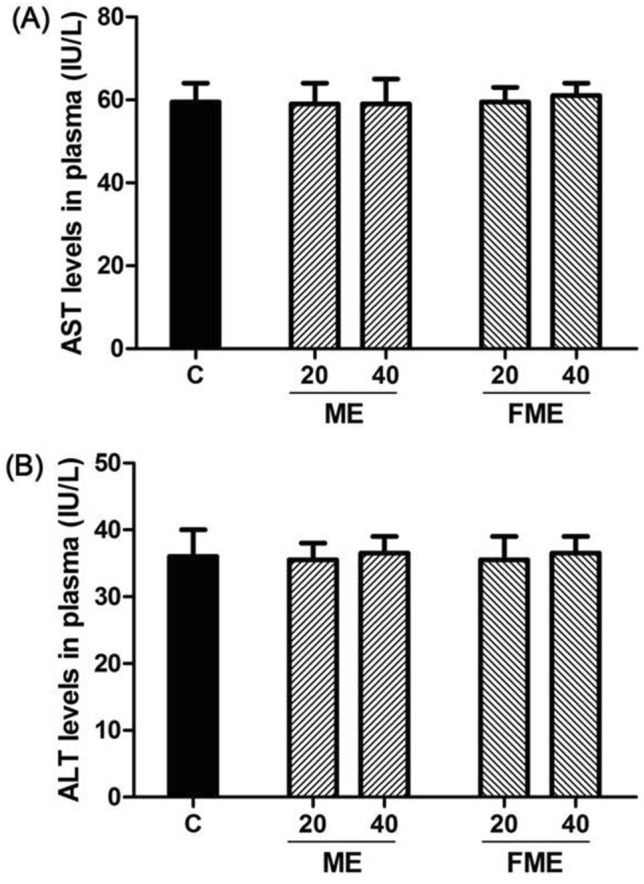

Hepatotoxicity due to ME and FME administration

Considering the unexpected liver dysfunctions possibly caused by the administration of natural product extracts, blood aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were assayed to verify effects on liver function in the animals after ME and FME administration for 6 weeks. When comparing the control group and the experimental groups, there were no differences in AST and ALT levels (Fig. 4). Thus, we believe that the administration of ME and FME did not cause any toxic effects on liver function under our experimental conditions.

Fig. 4.

Aspartate transaminase (AST) (A) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (B) levels in blood serum after 6 weeks of ME administration. C, water-administered control; ME20 and ME40: normal ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively); FME20 and FME40: fermented ME-administered groups (20 and 40 mg/kg body weight, respectively)

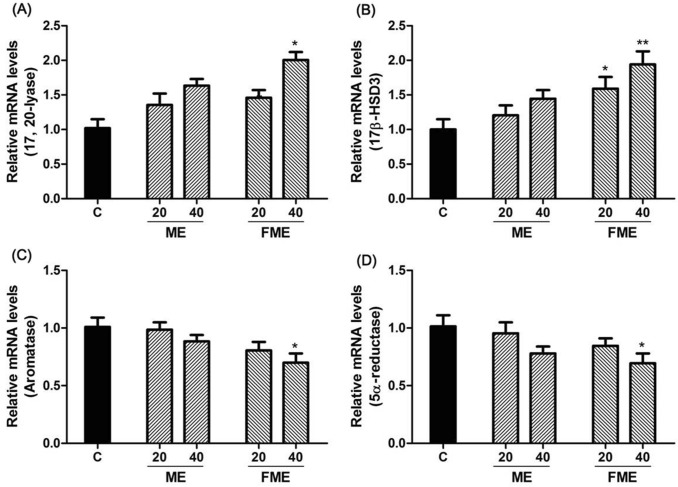

Effects of ME and FME administration on gene expression related to testosterone synthesis and degradation

To examine the mechanism of increasing the blood testosterone concentration by ME and FME, the TM3 cell line of mouse Leydig cells was treated with the extracts at concentrations of 20 and 40 µg/mL. Differences in gene expression related to testosterone synthesis and degradation were analyzed by real-time qPCR (Fig. 5). The relative mRNA levels of 17,20-lyase, which converts 17α-hydroxy pregnenolone into DHEA and androstenedione (testosterone precursors), increased by 1.36, 1.64, and 1.46 times in the ME20, ME40, and FME20 groups, respectively, which were not statistically significant (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the corresponding mRNA levels significantly increased with FME40 by 2.00 times (Fig. 5A). The relative mRNA levels of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 (17β-HSD3), which converts androstenedione into testosterone, increased in the ME20 and ME40 groups by 1.21 and 1.45 times, respectively, which were not statistically significant (Fig. 5B). However, the corresponding mRNA levels significantly increased in the FME20 and FME40 groups by 1.59 and 1.94 times, respectively (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, enzymes that metabolize testosterone to reduce the blood testosterone concentration (namely, aromatase, which converts testosterone to estradiol, and 5α-reductase, which converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone) were investigated (Fig. 5C, D). First, the expression levels of aromatase decreased by 0.98, 0.88, and 0.80 times in the ME20, ME40, and FME20 groups, respectively, compared to those in the control group but not significantly. In the FME40 group, the aromatase expression level significantly decreased by 0.69 times compared to that in the control group (Fig. 5C). Similar results were observed for 5α-reductase expression, which decreased with ME20, ME40 and FME20 by 0.94, 0.77, and 0.83 times, respectively, while 5α-reductase expression significantly decreased by 0.68 times in the FME40 group compared to those in the control group (Fig. 5D). These findings were in line with the increase in the free testosterone concentration in the animal experiment (Fig. 1C) and indicated that the MEs could stimulate the expression of enzymes that promote testosterone biosynthesis (17,20-lyase and 17β-HSD3) to increase the concentration, as well as reduce the expression of enzymes that metabolize testosterone (aromatase and 5α-reductase) to other substances, leading to an overall increase in the testosterone concentration.

Fig. 5.

Effects of Momordica charantia extracts (ME) on the expression of the 17,20-lyase (A), 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 (17β-HSD3) (B), aromatase (C), and 5α-reductase (D) genes in the TM3 cell line. C, control (not treated with any ME); ME20 and ME40: normal nonfermented ME-treated groups (20 and 40 µg/mL, respectively); FME20 and FME40: fermented ME-treated groups (20 and 40 µg/mL, respectively). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

The results obtained in this experiment suggest that MEs contain effective pharmacological activities that increase and restore free testosterone levels in aging male rats. In addition, FMEs exhibited better effects than the nonfermented extracts, and it is therefore believed that the content of bioactive molecules or the bioavailability of functional components present in MC is increased through the fermentation process. Therefore, further studies may be needed to analyze the active ingredients increased by fermentation. In conclusion, the FME showed a positive effect on male climacterium symptoms, and thus, it is expected that such extracts can be developed as a functional material or food that is effective in alleviating andropause.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the members of the Biomedical Research Institute at Jungwon University for their care and assistance in the animal experiment. This work was supported by a Jungwon University Research Grant (2019-009).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors declare any conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All of the authors complied with ethical standards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alam MA, Uddin R, Subhan N, Rahman MM, Jain P, Reza HM. Beneficial role of bitter melon supplementation in obesity and related complications in metabolic syndrome. J. Lipids. 2015;2015:496169. doi: 10.1155/2015/496169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaissie J, Roberts NH, Wang P, Yafi FA. Testosterone replacement therapy and components of the metabolic syndrome. Sex. Med. Rev. 2017;5:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson JF, Hidalgo S, Simons R, Verbruggen M. Preventive effects of lignan extract from flax hulls on experimentally induced benign prostate hyperplasia. J. Med. Food. 2014;17:650–656. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst SE, Yarrow JF. Injection of testosterone may be safer and more effective than transdermal administration for combating loss of muscle and bone in older men. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;308:E1035–E1042. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00111.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona G, Giagulli VA, Maseroli E, Vignozzi L, Aversa A, Zitzmann M, Saad F, Mannucci E, Maggi M. Testosterone supplementation and body composition: results from a meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2016;39:967–981. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham GR. Andropause or male menopause? Rationale for testosterone replacement therapy in older men with low testosterone levels. Endocr. Pract. 2013;19:847–852. doi: 10.4158/EP13217.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidiuk AJ, Broderick GA. Adult-onset hypogonadism: evaluation and role of testosterone replacement therapy. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2016;5:824–833. doi: 10.21037/tau.2016.09.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Wen JJ, Hu JL, Nie QX, Chen HH, Xiong T, Nie SP, Xie MY. Fermented Momordica charantia L. juice modulates hyperglycemia, lipid profile, and gut microbiota in type 2 diabetic rats. Food Res. Int. 2019;121:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong ZG, Zhang J, Xu YJ. Metabolomics reveals that Momordica charantia attenuates metabolic changes in experimental obesity. Phytother. Res. 2017;31:296–302. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutfinger T. Polyphenols in olive oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1981;58:966–968. [Google Scholar]

- Haider A, Yassin A, Haider KS, Doros G, Saad F, Rosano GM. Men with testosterone deficiency and a history of cardiovascular diseases benefit from long-term testosterone therapy: observational, real-life data from a registry study. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:251–261. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S108947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan J, Barkin J. Testosterone deficiency syndrome: benefits, risks, and realities associated with testosterone replacement therapy. Can. J. Urol. 2016;23:20–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildreth KL, Barry DW, Moreau KL, Vande Griend J, Meacham RB, Nakamura T, Wolfe P, Kohrt WM, Ruscin JM, Kittelson J, Cress ME, Ballard R, Schwartz RS. Effects of testosterone and progressive resistance exercise in healthy, highly functioning older men with low-normal testosterone levels. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2013;98:1891–1900. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J. Gerontol. A-Biol. 2012;67:1140–1152. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao CY, Chen YM, Hsu YJ, Huang CC, Sung HC, Chen SS. Supplementation with Hualian No. 4 wild bitter gourd (Momordica charantia Linn. var. abbreviata ser.) wild bitter gourd extract increases anti-fatigue activities and enhances exercise performance in mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017;79:1110–1119. doi: 10.1292/jvms.17-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Chen H, Zhou X, Wu X, Hu E, Jiang Z. Inhibition effects of chlorogenic acid on benign prostatic hyperplasia in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017;809:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismaeel N, Wang R. Testosterone replacement-freedom from symptoms or hormonal shackles? Sex. Med. Rev. 2017;5:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, Shen M, Zhang F, Xie J. Recent advances in Momordica charantia: functional components and biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2555. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khourdaji I, Lee H, Smith RP. Frontiers in hormone therapy for male infertility. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018;7:S353–S366. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.04.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Park CH, Jung HY, Jeong J, Hong HU, Kim JB. Bitter melon (Momordica charantia) extract enhances exercise capacity in mouse model. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2016;29:506–512. [Google Scholar]

- Koriem KMM, Fathi GE, Salem HA, Akram NH, Gamil SA. Protective role of pectin against cadmium-induced testicular toxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Toxicol. Mech. Method. 2013;23:263–272. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2012.748857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low KL, Tomm RJ, Ma C, Tobiansky DJ, Floresco SB, Soma KK. Effects of aging on testosterone and androgen receptors in the mesocorticolimbic system of male rats. Horm. Behav. 2020;120:104689. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather JP. Establishment and characterization of two distinct mouse testicular epithelial cell lines. Biol. Reprod. 1980;23:243–252. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod23.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MI, Isla MI, Sampietro AR, Vattuone MA. Comparison of the free radical-scavenging activity of propolis from several regions of Argentina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgentaler A, Khera M, Maggi M, Zitzmann M. Commentary: Who is a candidate for testosterone therapy? A synthesis of international expert opinions. J. Sex. Med. 2014;11:1636–1645. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouser JG, Loprinzi PD, Loenneke JP. The association between physiologic testosterone levels, lean mass, and fat mass in a nationally representative sample of men in the United States. Steroids. 2016;115:62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz R, Anjum FM, Butt MS, Mahr Un N. Dietary supplementation of bitter gourd reduces the risk of hypercholesterolemia in cholesterol fed sprague dawley rats. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016;29:1565–1570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarni R, Purnama D, Umar S, Eni H. The effect of fermentation on total phenolic, flavonoid and tannin content and its relation to antibacterial activity in jaruk tigarun (Crataeva nurvala, Buch HAM.) Int. Food Res. J. 2016;23:309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Kim WK, Kim HP, Yoon YG. The efficacy of lowering blood glucose levels using the extracts of fermented bitter melon in the diabetic mice. J. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2015;58:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ring J, Welliver C, Parenteau M, Markwell S, Brannigan RE, Kohler TS. The utility of sex hormone-binding globulin in hypogonadism and infertile males. J. Urology. 2017;197:1326–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JY, Kang HR, Cho SK. Changes over the fermentation period in phenolic compounds and antioxidant and anticancer activities of blueberries fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Food Sci. 2019;84:2347–2356. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvati G, Genovesi G, Marcellini L, Paolini P, De Nuccio I, Pepe M, Re M. Effects of Panax Ginseng C.A. Meyer saponins on male fertility. Panminerva Med. 1996;38:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E, Pastuszak AW, Khera M. Erectile dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risks: facts and controversies. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017;6:28–36. doi: 10.21037/tau.2016.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Fujita S, Iemitsu M. Acute administration of diosgenin or dioscorea improves hyperglycemia with increases muscular steroidogenesis in STZ-induced type 1 diabetic rats. J. Steroid Biochem. 2014;143:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saygin M, Asci H, Ozmen O, Cankara FN, Dincoglu D, Ilhan I. Impact of 245 GHz microwave radiation on the testicular inflammatory pathway biomarkers in young rats: the role of gallic acid. Environ. Toxicol. 2016;31:1771–1784. doi: 10.1002/tox.22179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi F, Ambigaipalan P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: antioxidant activity and health effects—a review. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;18:820–897. [Google Scholar]

- Shea JL, Wong PY, Chen Y. Free testosterone: clinical utility and important analytical aspects of measurement. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2014;63:59–84. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-800094-6.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storer TW, Basaria S, Traustadottir T, Harman SM, Pencina K, Li Z, Travison TG, Miciek R, Tsitouras P, Hally K, Huang G, Bhasin S. Effects of testosterone supplementation for 3 years on muscle performance and physical function in older men. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2017;102:583–593. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SR, Meadowcraft LM, Williamson B. Prevalence, pathophysiology, and management of androgen deficiency in men with metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or both. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:780–792. doi: 10.1002/phar.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ryu HK. The effects of Momordica charantia on obesity and lipid profiles of mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2015;9:489–495. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2015.9.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen F, Ye L, Zirkin B, Chen H. Steroidogenesis in Leydig cells: effects of aging and environmental factors. Reproduction. 2017;154:R111–R122. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PL, Pu HF, Chen SY, Wang SW, Wang PS. Effects of catechin, epicatechin and epigallocatechin gallate on testosterone production in rat Leydig cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;110:333–342. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.