This cross-sectional study compares stress during investigational optical coherence tomography imaging to that during binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy for retinopathy of prematurity.

Key Points

Question

Is infant stress from optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging different from that of clinical binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examinations for retinopathy of prematurity?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 71 eye examinations of 16 infants, several indicators of behavioral stress (crying and facial expression) and physiologic stress (heart rate) were less during OCT imaging than BIO, even though the time for OCT imaging was longer.

Meaning

While the clinical relevance of adding or substituting OCT imaging of retinopathy of prematurity is yet to be determined, OCT imaging may be less stressful to the infant compared with BIO by a trained ophthalmologist.

Abstract

Importance

Binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a well-known cause of repeated preterm infant stress.

Objective

To compare stress during investigational optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging to that during BIO for ROP.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study examined infants at the bedside in the intensive care nursery. Consecutive preterm infants enrolled in Study of Eye Imaging in Preterm Infants (BabySTEPS) who had any research OCT imaging as part of the study. Patients were recruited from June to November 2019, and analysis began April 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Infant stress was measured using modified components of a neonatal pain assessment tool before (baseline) and during OCT imaging and BIO examination of each eye.

Results

For 71 eye examinations of 16 infants (mean [SD] gestational age, 27 [3] weeks; birth weight, 869 [277] g), change from baseline to each eye examination was lower during OCT imaging than during BIO and the difference between OCT imaging and BIO at each eye examination was significant for the following: infant cry score (first eye examination: mean [SD], 0.03 [0.3] vs 1.68 [1.2]; −1.65 [95% CI, −1.91 to −1.39]; second eye examination: mean [SD], 0.1 [0.3] vs 1.97 [1.2]; −1.87 [95% CI, −2.19 to −1.54]), facial expression (first eye: 3 [4%] vs 59 [83%]; −79% [95% CI, −87% to −72%]; second eye: 4 [6%] vs 61 [88%]; −83% [95% CI, −89% to −76%]), and heart rate (first eye: mean [SD], −7 [16] vs 13 [18]; −20 [95% CI, −26 to −14]); second eye: mean [SD], −3 [18] vs 20 [20] beats per minute; −23 [95% CI, −29 to −18]) (P < .001 for all). Change in respiratory rate and oxygen saturation did not differ between OCT imaging and BIO.

Conclusions and Relevance

While the role of OCT alone or in combination with BIO is currently unknown for ROP, these findings suggest that investigational OCT imaging of ROP is less stressful than BIO examination by a trained ophthalmologist.

Introduction

Survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants, including periviable infants (22-25 weeks’ gestational age), have improved over the past 20 years. However, despite these achievements, long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes for these infants remain a concern.1,2,3 Prolonged exposure to early-life stress while in the intensive care nursery (ICN) causes alterations in the neural connectome leading to cognitive deficits later in life.4,5,6 Stressors in the ICN include physiological stressors such as sepsis, environmental stressors such as excessive light, and experiential stressors such as blood draws.4,7,8 Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) examination by a trained ophthalmologist usually entails placement of an eyelid speculum, mydriatic drops, retinal illumination by the bright light of a binocular indirect ophthalmoscope, and pressure on the outer surface of the eye.9 Binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) is a repeated experiential stressor/painful procedure for infants10,11,12,13 and can produce changes in heart rate, both tachycardia and bradycardia, and apnea during and after examination.11,14,15,16 Use of oral sucrose and intranasal fentanyl have been reported to reduce pain associated with retinal examination without increasing the risk of respiratory depression; however, their safety and efficacy need to be verified.17,18 Approximately 70 000 infants per year in the United States receive 1 or more BIO examinations for ROP screening.19

Retinal imaging with a fundus camera as an adjunct to BIO is useful for documentation and communication of diagnosis, ROP progression, and response to treatment.20,21 Images acquired by trained and accredited nonphysician health care professionals using contact widefield retinal cameras have been uploaded to telemedicine platforms, and protocols have been developed and validated to cope with the public health challenge of an increasing preterm infant population, disproportionate to the number of ROP specialists.22,23,24 Similar to BIO, contact retinal imaging requires use of topical anesthetic, dilation drops, eye manipulation, and bright light exposure, which have been associated with bradycardia and apnea during and after imaging.23,24,25,26,27,28,29 Although retinal imaging using a noncontact camera can be less stressful compared with BIO,21 the bright light is still a potential infant stressor.

Handheld optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a novel imaging technology whose use aids in the diagnosis and management of pediatric retinal diseases.30,31,32 The en face and cross-sectional imaging of retinal vasculature and substructures provides novel visualization of ROP and of cell layer changes during retinal development and ROP.32,33 Most of these are not visible using BIO. We and other researchers have developed faster investigational OCT systems to image moving eyes of awake infants in the ICN34,35 and to evaluate vascular disease in eyes with ROP.36 Bedside noncontact, infrared OCT imaging does not use bright visible light and does not require pupil dilation, although the latter facilitates peripheral retinal imaging.37 In a noncomparative study in 42 infants, our group found no significant association of OCT with preterm infant heart rate or adverse events.30 We hypothesize that the noncontact nature and lack of visible light with infrared OCT will be associated with less infant stress compared with standard BIO. Here, we test this hypothesis at the bedside. While an overall decrease in infant stress relies on the future potential for OCT to replace BIO, this study still informs us of the relative stress of this imaging.

Methods

The prospective observational Study of Eye imaging in Preterm Infants (BabySTEPS) is approved by the Duke University Health System institutional review board, registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02887157), and adheres to the guidelines of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.38 Infants were eligible for inclusion if they qualified for ROP screening per current guidelines9 with written consent by a parent or legal guardian. Parents were not given any incentive or compensation for participation in this study. We included 16 infants from BabySTEPS (eMethods in the Supplement) who had 73 examination sessions eligible for this study and 71 of 73 visits with both OCT and BIO. Patients were recruited from June to November 2019.

Clinical BIO was performed in the Duke University Medical Center ICN by 1 of 2 expert fellowship-trained pediatric ophthalmologists (S.F.F. and S.G.P.). Infant eyes were pharmacologically dilated (cyclopentolate hydrochloride and phenylephrine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution) before clinical examination. Bedside ROP examinations typically involved swaddling, positioning the infant horizontally in the bed for access, instilling anesthetic eye drops (proparacaine, 0.5%), inserting an eyelid speculum, and using a scleral depressor, oral sucrose, and pacifier as needed. Bedside, handheld research OCT was performed per study protocol39 by certified imagers with the Duke investigational swept-source OCT system and on the same morning as the clinical ROP examination. OCT imaging typically lasted for 15 minutes for capture of structural OCT images of the macula, optic nerve head, and retinal periphery of both eyes and OCT angiography for most infants. At the recommendation of the bedside nurse, for 66 OCT sessions, infants were positioned similar to that for BIO for imaging, while for 5 sessions, imaging was performed without moving the infant. For OCT, infants were swaddled, eyelids were held open with the imager’s fingertips, and no eyelid speculum was used (comparable with published video of imaging40). We recorded the order of OCT and BIO, which varied by infant based on ICN workflow. We also recorded the use of a pacifier and/or oral sucrose, which was used per care team preference during OCT or BIO.

Infant stress data were collected at the bedside by 1 of 2 observers (S.M. and N.S.) using modified components of the CRIES neonatal pain measurement score (crying, requires increased oxygen administration, increased vital signs, expression, sleeplessness)14 at 3 time points for both OCT and BIO. The modified CRIES measures captured were crying, facial expression, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Additional stress events, including bradycardia, tachycardia, and oxygen desaturation, based on alarm limits set per ICN protocol for each infant for that day, were also recorded. All are defined in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The 3 time points of data collection were baseline (within 10 minutes before OCT/BIO) and during the first and second eye OCT/BIO. OCT imagers and BIO examiners were masked to data collection. Interobserver agreement for the collection of stress factors are reported in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

We performed all statistical analyses using R version 3.5.1 (R foundation for Statistical Computing). Infant demographics, including gestational age, birth weight, postmenstrual age, sex, race, and ethnicity, were extracted from the medical record. We performed regression analyses using generalized estimating equations to account for the correlation in stress measures among multiple episodes per infant to (1) assess differences in the duration of OCT and BIO sessions and use of comfort aids (ie, sucrose and a pacifier) per session, (2) evaluate occurrence of stress events (ie, bradycardia, tachycardia, and oxygen desaturation), and (3) assess change in primary stress factors from baseline to first and second eye OCT/BIO. All comparisons between OCT and BIO were adjusted for the sequence of examination. Two-sided P values were significant at less than .05. Analysis began April 2020.

Results

The 16 infants had a mean (SD) gestational age of 27 (3) weeks and a mean (SD) birth weight of 869 (277) g. At the time of OCT and BIO, postmenstrual age ranged from 31 to 51 weeks. Nine of 16 infants (56%) were not using any respiratory support at any of the OCT/BIO sessions; 7 infants (44%) either required a ventilator, continuous positive airway pressure, or had a nasal cannula at 1 or more OCT/BIO sessions affecting a total of 33 OCT/BIO sessions (46%). All infants were either using partial or full enteral feeds at the time of 1 or more OCT/BIO sessions. OCT was performed first in 44 sessions (62%). When OCT was performed first, the mean (SD) duration between imaging and examination was longer (43 [31] min) than when BIO was performed first (14 [25] min) (95% CI, −43.39 to −15.13; P < .001). Baseline infant health information, examination details, and use of comfort aids for OCT and BIO are reported in eTable 3 in the Supplement and Table 1.

Table 1. Comfort Support Used During Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Imaging and Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscopy (BIO) Examination for Retinopathy of Prematurity Screening.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Difference (95% CI), % | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT imaging (n = 71) | BIO examination (n = 71) | |||

| Examination duration, mean (SD), min | 17 (4) | 5 (2) | 12.1 (11.0 to 13.1) | <.001 |

| Pharmacological dilation | 67 (94) | 71 (100) | −5.3 (−9.4 to −1.1) | <.001 |

| Eyelid speculum | 0 | 71 (100) | −100 (−100 to −100) | <.001 |

| Sucrose | 13 (18) | 55 (78) | −59 (−79 to −38.9) | <.001 |

| Pacifier | 33 (46) | 41 (58) | −11.3 (−32.3 to 9.7) | .29 |

| Artificial tears | 3 (4) | 0 | 4.1 (0.1 to 8.2) | <.001 |

Primary Stress Factors

Stress factors (ie, cry, facial expression, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation) at baseline and first and second eye OCT/BIO sessions are depicted in the eFigure in the Supplement and reported in Table 2. At baseline, except for respiratory rate, these were comparable between OCT and BIO. Observers noted widely fluctuating respiratory rates at baseline and throughout imaging for 61 OCT (86%) and 48 BIO sessions (68%). During the first and second eye OCT/BIO sessions, infants’ cry score (first eye: 95% CI, −1.92 to −1.31; P < .001; second eye: 95% CI, −2.21 to −1.47; P < .001) and facial expression score (first eye: 95% CI, −91.19 to −76.57; P < .001; second eye: 95% CI, −95.87 to −77.83; P < .001) were at a lower grade for a higher percentage of infants during OCT vs BIO. Mean (SD) heart rate was lower during OCT of the first and second eye (163 [20] and 166 [19] beats per minute, respectively) vs BIO (180 [16] and 187 [16] beats per minute, respectively) (first eye: 95% CI, −21.89 to −13.60; second eye: 95% CI, −24.66 to −17.77; P < .001 for all at both time points). Mean respiratory rate was higher for OCT vs BIO at baseline (95% CI, 0.82-11.54; P = .02) and during the first (95% CI, 2.70-13.72; P = .003) and second eye OCT/BIO sessions (95% CI, −0.07 to 6.48; P = .05). Oxygen saturation did not differ during the first (95% CI, −0.28 to 4.37; P = .08) and second eye during OCT vs BIO sessions (95% CI, −0.23 to 4.08; P = .08) (eFigure in the Supplement; Table 2).

Table 2. Primary Stress Outcomes Measured at Different Times for Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Imaging and Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscopy (BIO) Examination.

| Measure | No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 71) | First eye imaging/examination (n = 71) | Second eye imaging/examination (n = 69) | |||||

| OCT | BIO | P value | OCT | BIO | OCT | BIO | |

| Crying | |||||||

| 0 = No crying | 65 (92) | 68 (96) | .55 | 64 (90) | 12 (16) | 56 (81) | 5 (7) |

| 1 = Moans or cries minimally | NA | 2 (3) | 6 (9) | 26 (37) | NA | 26 (38) | |

| 2 = Appropriate crying | 6 (8) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 7 (10) | 13 (19) | 7 (10) | |

| 3 = High pitched | NA | NA | NA | 21 (30) | NA | 24 (35) | |

| 4 = Inconsolable | NA | NA | NA | 5 (7) | NA | 7 (10) | |

| Facial expression | |||||||

| 0 = Relaxed with no grimace | 66 (93) | 66 (93) | >.99 | 66 (93) | 7 (10) | 62 (90) | 4 (5) |

| 1 = Grimace only | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 64 (90) | 7 (10) | 69 (95) | |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min | 169 (20) | 167 (19) | .35 | 163 (20) | 180 (16) | 166 (19) | 187 (16) |

| Respiratory rate, mean (SD), breaths/min | 56 (20) | 50 (19) | .02 | 54 (16) | 46 (12) | 53 (17) | 49 (13) |

| Oxygen saturation, mean (SD), % | 97 (4) | 96 (6) | .53 | 97 (3) | 95 (6) | 97 (4) | 95 (6) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

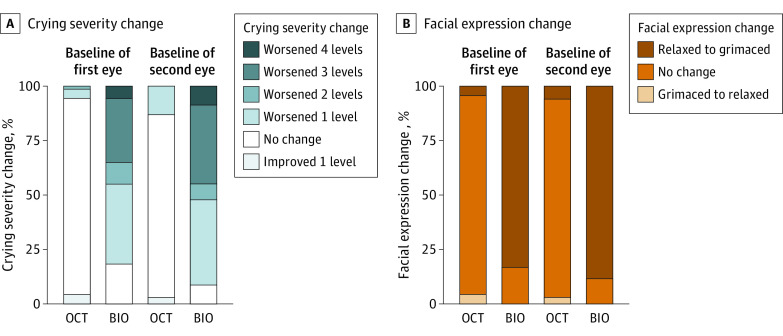

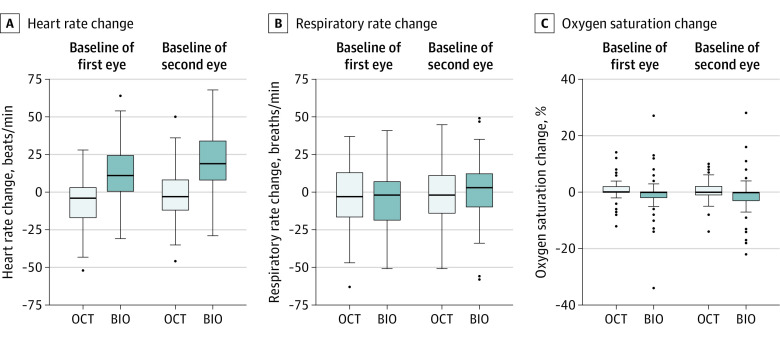

Change in cry score from baseline to first and second eye sessions was lower for OCT (mean [SD], 0.03 [0.3] for the first eye and 0.1 [0.3] for the second eye) vs BIO (mean [SD], 1.68 [1.2] for the first eye and 1.97 [1.2] for the second eye). The difference in cry score between OCT and BIO was −1.65 (95% CI, −1.91 to −1.39) for the first eye and −1.87 (95% CI, −2.19 to −1.54) for the second eye (P < .001). With OCT, far fewer infants had worsening of facial expression score from baseline to during the first and second eye sessions (3 of 71 [4%] and 4 of 69 [6%], respectively) than with BIO (59 of 71 [83%] and 61 of 69 [88%], respectively), and the difference between OCT and BIO was −79% (95% CI, −87% to −72%) vs −83% (95% CI, −89% to −76%), respectively (P < .001) (Figure 1 and Table 3). During OCT imaging, mean heart rate, compared with baseline, decreased by a mean (SD) of 7 (16) beats per minute (first eye) and by 3 (18) beats per minute (second eye). During BIO examination, heart rate increased from baseline by a mean (SD) of 13 (18) beats per minute (first eye) and by 20 (20) beats per minute (second eye). Change in heart rate from baseline to during first eye OCT imaging was a mean of 20 beats per minute lower than to during BIO (95% CI, −26 to −14; P < .001). This difference in change in heart rate between OCT and BIO was also found from baseline to during the second eye OCT/BIO session (ΔBIO − ΔOCT = −23 beats per minute; 95% CI, −29 to −18; P < .001) (Figure 2 and Table 3). By contrast, there was no significant difference between changes in respiratory rate or oxygen saturation from baseline for OCT and BIO. For the first eye undergoing OCT/BIO, the mean change from baseline in respiratory rate was 2 breaths per minute lower during BIO (95% CI, −6 to 10; P = .63) and mean change in oxygen saturation was 1.7% lower (95% CI, −0.67 to 4.16; P = .16). For the second eye undergoing OCT/BIO, mean change from baseline in respiratory rate was 3 breaths per minute higher during BIO (95% CI, −9 to 3; P = .30) and mean change in oxygen saturation was 1.6% lower (95% CI, −0.33 to 3.60; P = .10) (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Figure 1. Infants With Change in Behavioral Measures of Stress From Baseline to During First and Second Eye OCT Imaging/BIO Examination.

Baseline values were reported within 10 minutes before the optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging/binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination.

Table 3. Change in Stress Outcome Measures From Baseline to First and Second Eye Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) Imaging/Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscopy (BIO) Examination.

| Measure | Change from baseline to first eye OCT imaging/BIO examination (n = 71) | Change from baseline to second eye OCT imaging/BIO examination (n = 69) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT | BIO | Difference (95% CI)a | P value | OCT | BIO | Difference (95% CI)a | P value | |

| Cry increase, mean (SD) | 0.03 (0.38) | 1.68 (1.24) | −1.65 (−1.91 to −1.39) | <.001 | 0.11 (0.39) | 1.97 (1.21) | −1.87 (−2.19 to −1.54) | <.001 |

| Facial expression worsened, No. (%) | 3 (4) | 59 (83) | −79% (−87 to −72) | <.001 | 4 (6) | 61 (88) | −83% (−89 to −76) | <.001 |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min | −7 (16) | 13 (18) | −20 (−26 to −14) | <.001 | −3 (18) | 20 (20) | −23 (−29 to −18) | <.001 |

| Respiratory rate, mean (SD), breaths/min | −2 (20) | −4 (20) | 2 (−6 to 10) | .63 | −3 (21) | −0.4 (21) | −3 (−9 to 3) | .30 |

| Oxygen saturation, mean (SD), % | 0.87 (3.70) | −0.87 (6.88) | 1.75 (−0.67 to 4.16) | .16 | 0.48 (3.7) | −1.10 (6.81) | 1.63 (−0.33 to 3.60) | .10 |

Difference in the mean change from baseline to during first eye and second eye OCT imaging and BIO examination per infant.

Figure 2. Change in Physiologic Measures of Stress From Baseline to During First and Second Eye OCT Imaging/BIO Examination.

Baseline values were reported within 10 minutes before optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging/binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination.

When we compared the difference in primary stress factors when OCT was performed first vs when BIO was performed first, we found no difference between these measures irrespective of the OCT/BIO order (results not shown).

Stress Events During OCT Imaging and BIO Examination

Stress events occurred 12 times (17%) during OCT and 18 times (25%) during BIO. Bradycardia occurred in 3 sessions (4%) during OCT and in 1 session (1%) during BIO, tachycardia was recorded in 1 session (1%) during OCT and 8 sessions (11%) during BIO, and oxygen desaturation in 8 sessions (12%) during OCT and in 9 sessions (14%) during BIO (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Five of 8 desaturation events (62%) occurred more than once during a single OCT session, 6 of 9 desaturation events (67%) occurred more than once during BIO, as did 3 of 8 events of tachycardia (37%) during BIO. It was interesting to note that all of these stress events were isolated episodes restricted to either OCT or BIO and did not co-occur during both examinations for any infant. The lower mean (SD) limit oxygen saturation alarm was 86% (4%) during all examinations when desaturation ensued. At the nurse’s recommendation, OCT was stopped in 1 infant after the first eye was imaged because of a malfunctioning oxygen saturation monitor. We did not find an association between occurrence of stress events and the order of examination.

Discussion

In this study, we found a lower association of behavioral stress indicators (crying and facial expression) and a physiologic indicator (heart rate) with outcomes during OCT compared with BIO, even though the time taken for research OCT imaging was longer. We also observed a trend toward lower occurrence of tachycardia during OCT compared with BIO. BabySTEPS and other OCT-based studies are evaluating bedside retinal neurovascular imaging of preterm infants being screened for ROP.31,39,41,42,43 Therefore, comparing the association of OCT to that of the criterion standard BIO with infant stress is valuable for the development of tools such as OCT that can minimize infant stress and potentially aid with the diagnosis and treatment for ROP.

Our findings during BIO confirmed previous reports (eTable 5 in the Supplement) that BIO is undeniably a stressful procedure for infants. Some of the factors contributing to this stress include physical manipulation of the eye and bright light illumination. Invisible near-infrared illumination for OCT-based screening is better tolerated, as would be expected. The mean increase in heart rate of 13 to 20 beats per minute from baseline during BIO may be attributed to an adrenergic response to the procedure44 and is comparable with earlier studies of infant stress response to BIO and to imaging with a contact fundus camera.26,29 In contrast, during speculum insertion, Laws et al44 and Clarke et al45 reported a drop in the heart rate resulting from the oculocardiac reflex. Zores et al46 reported increase in heart rate with increased ICN light levels, demonstrating that very preterm infants may be sensitive to small changes in ambient light. Despite ICN guidelines specifying a target light level to ensure the comfort of neonates47 and use of phototherapy masks to diminish stress from ambient light on dilated pupils,15 there is inadequate information on optimal light exposure during ROP examination, with illumination sufficient for the ophthalmologist to determine the retinal status.

Preterm infants have a median of 3 sequential ROP screening examinations while in the ICN,25 and the youngest infants commonly have more. Lower stress of OCT imaging on infants may be beneficial by possibly decreasing the neurobiological effect contributed by stress of repeated BIO examinations. While the use of nonpharmacologic comfort measures have been implemented during BIO to try to decrease infant stress, optimal combination of comfort measures remains undefined because of gaps in available evidence.8,48 While swaddling, the use of pacifiers, and sucrose have been recommended for minor procedural pain,10 Rush et al11 found no significant difference in level of stress during eye examination between infants who received comfort care vs those who did not. This suggests that the aforementioned comfort measures cannot systematically ameliorate pain during ROP examinations.11 Moreover, sucrose does not have any effect on the neural activity of nociception (ie, pain)-evoked circuits in the spinal cord or brain,8 indicating that it may be more of a distraction for the infant rather than an aid to decrease pain. This limited understanding of the mechanism and efficacy of oral sucrose raises the question of its benefit in reducing early-life stress and improving long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants.8

Our results showed that lower stress levels in infants were associated with OCT compared with BIO. Lower change in the infant cry grade, facial expression, and heart rate from baseline to during OCT may be attributed to the elimination of known stress-inducing examination aids used with BIO such as the eyelid speculum, scleral depressor, and bright visible light. During OCT, we reported lower number of stress events, mainly tachycardia, compared with BIO, despite longer imaging time. To monitor these stress events, we relied on preset alarms for each infant, as opposed to clinically defined bradycardia (<80 bpm), tachycardia (>200 bpm), and oxygen desaturation (<80%).25 While OCT images have not been shown to be equivalent to BIO for ROP determination, this has been the focus of multiple studies demonstrating the future potential.34,36,43 Reduction in early-life stress might be possible in the future if OCT imaging proved comparable with BIO for screening. Such an advance could be beneficial for long-term neurodevelopment in preterm infants.

Limitations

Fundamental limitations of our study include limited number of infants studied, which may not be representative of the entire population, the bias of BIO being performed first in unstable infants, and lack of comparison with retinal imaging with a contact fundus camera (which has been recognized as inducing infant stress comparable with BIO).26,29 The clinical relevance of adding or substituting OCT for BIO in ROP is unknown at this time. We recognize that OCT imaging is not readily available or used by most ICNs in the United States or the rest of the world. We also realize that OCT is currently limited outside of research and the commercial spectral-domain OCT systems are limited in their view of the periphery, therefore warranting BIO examination for these infants. While assessment of stress, pain, and discomfort in this population is challenging, we used modified components of the CRIES neonatal pain measurement score, which was highly rated at the time our study was designed.14 A limitation that may relate to the lack of difference in oxygen saturation is that we did not record change in supplemental oxygen during the examinations. More recently, other scales such as Neonatal Pain, Agitation and Sedation Scale, and the Bernese Pain Scale Neonates have been assessed and found to have a high interrater reliability and high validity.8 However, the CRIES score also includes both behavioral and physiologic markers similar to the newer pain scales.

Conclusions

Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment of infants with ROP, the neonatal community has made limited improvements in diminishing infant stress during ROP screening.17 Our study identifies a novel, potentially less stressful screening technique (ie, noncontact OCT) that holds promise for future clinical ROP screening. We also demonstrate that OCT adds minimal stress to the infant when performed alongside BIO. Further validation of these findings, and potentially a large trial through the collaboration of ophthalmologists and neonatologists to evaluate OCT imaging for ROP screening and neonatal stress, would be beneficial for this vulnerable population.

eMethods.

eTable 1. List and description of events collected for optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination during the study

eTable 2. Intra-observer reproducibility results for both the observers for the collection of stress factors in 5 infants with 11 examinations during optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO)

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort and categories of respiratory support used during the optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination for retinopathy of prematurity screening

eTable 4. Occurrence of stress events for optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination

eTable 5. Comparison of studies reporting the impact of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) examinations with imaging modalities versus with the standard binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy examination on infant stress

eFigure. Behavioral and physiologic measures of stress at baseline (within 10 minutes before optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging/binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination), and during first and second eye OCT imaging/BIO examination

References

- 1.Younge N, Goldstein RF, Bann CM, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes among periviable infants. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):617-628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Arnaud C, et al. ; EPIPAGE-2 writing group . Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039-1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nist MD, Harrison TM, Steward DK. The biological embedding of neonatal stress exposure: a conceptual model describing the mechanisms of stress-induced neurodevelopmental impairment in preterm infants. Res Nurs Health. 2019;42(1):61-71. doi: 10.1002/nur.21923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith GC, Gutovich J, Smyser C, et al. Neonatal intensive care unit stress is associated with brain development in preterm infants. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(4):541-549. doi: 10.1002/ana.22545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duerden EG, Grunau RE, Guo T, et al. Early procedural pain is associated with regionally-specific alterations in thalamic development in preterm neonates. J Neurosci. 2018;38(4):878-886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0867-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newnham CA, Inder TE, Milgrom J. Measuring preterm cumulative stressors within the NICU: the Neonatal Infant Stressor Scale. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(9):549-555. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson C, Miller SP, El-Dib M, Massaro AN, Inder TE. The influence of pain, agitation, and their management on the immature brain. Pediatr Res. 2020;88(2):168-175. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0744-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fierson WM; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Ophthalmology; American Academy of Ophthalmology; American Association For Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Association of Certified Orthoptists . Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20183061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand KJ; International Evidence-Based Group for Neonatal Pain . Consensus statement for the prevention and management of pain in the newborn. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(2):173-180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rush R, Rush S, Ighani F, Anderson B, Irwin M, Naqvi M. The effects of comfort care on the pain response in preterm infants undergoing screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Retina. 2005;25(1):59-62. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200501000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell AJ, Green A, Jeffs DA, Roberson PK. Physiologic effects of retinopathy of prematurity screening examinations. Adv Neonatal Care. 2011;11(4):291-297. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e318225a332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabska J, Walden P, Lerer T, et al. Can oral sucrose reduce the pain and distress associated with screening for retinopathy of prematurity? J Perinatol. 2005;25(1):33-35. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krechel SW, Bildner J. CRIES: a new neonatal postoperative pain measurement score: initial testing of validity and reliability. Paediatr Anaesth. 1995;5(1):53-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.1995.tb00242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szigiato A-A, Speckert M, Zielonka J, et al. Effect of eye masks on neonatal stress following dilated retinal examination: the MASK-ROP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(11):1265-1272. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.3379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan JBC, Dunbar J, Hopper A, Wilson CG, Angeles DM. Differential effects of the retinopathy of prematurity exam on the physiology of premature infants. J Perinatol. 2019;39(5):708-716. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0331-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sindhur M, Balasubramanian H, Srinivasan L, Kabra NS, Agashe P, Doshi A. Intranasal fentanyl for pain management during screening for retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. J Perinatol. 2020;40(6):881-887. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-0608-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandasamy Y, Smith R, Wright IM, Hartley L. Pain relief for premature infants during ophthalmology assessment. J AAPOS. 2011;15(3):276-280. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binenbaum G, Bell EF, Donohue P, et al. ; G-ROP Study Group . Development of modified screening criteria for retinopathy of prematurity: primary results from the Postnatal Growth and Retinopathy of Prematurity Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(9):1034-1040. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.2753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fierson WM, Capone A Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Ophthalmology; American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Association of Certified Orthoptists . Telemedicine for evaluation of retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e238-e254. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prakalapakorn SG, Stinnett SS, Freedman SF, Wallace DK, Riggins JW, Gallaher KJ. Non-contact retinal imaging compared to indirect ophthalmoscopy for retinopathy of prematurity screening: infant safety profile. J Perinatol. 2018;38(9):1266-1269. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0160-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darlow BA, Gilbert C. Retinopathy of prematurity: a world update. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43(6):315-316. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinekar A, Rao SV, Murthy S, et al. A novel, low-cost, wide-field, infant retinal camera, “neo”: technical and safety report for the use on premature infants. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2019;8(2):2. doi: 10.1167/tvst.8.2.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami Y, Jain A, Silva RA, Lad EM, Gandhi J, Moshfeghi DM. Stanford University Network for Diagnosis of Retinopathy of Prematurity (SUNDROP): 12-month experience with telemedicine screening. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(11):1456-1460. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.138867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wade KC, Pistilli M, Baumritter A, et al. Safety of retinopathy of prematurity examination and imaging in premature infants. J Pediatr. 2015;167(5):994-1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhaliwal CA, Wright E, McIntosh N, Dhaliwal K, Fleck BW. Pain in neonates during screening for retinopathy of prematurity using binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy and wide-field digital retinal imaging: a randomised comparison. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95(2):F146-F148. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.168971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fung THM, Abramson J, Ojha S, Holden R. Systemic effects of optos versus indirect ophthalmoscopy for retinopathy of prematurity screening. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(11):1829-1832. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moral-Pumarega MT, Caserío-Carbonero S, De-La-Cruz-Bértolo J, Tejada-Palacios P, Lora-Pablos D, Pallás-Alonso CR. Pain and stress assessment after retinopathy of prematurity screening examination: indirect ophthalmoscopy versus digital retinal imaging. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee AN, Watts P, Al-Madfai H, Manoj B, Roberts D. Impact of retinopathy of prematurity screening examination on cardiorespiratory indices: a comparison of indirect ophthalmoscopy and retcam imaging. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(9):1547-1552. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin N, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2678-2685. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erol MK, Ozdemir O, Turgut Coban D, et al. Macular findings obtained by spectral domain optical coherence tomography in retinopathy of prematurity. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:468653. doi: 10.1155/2014/468653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Mangalesh S, Dandridge A, et al. Spectral-domain OCT findings of retinal vascular-avascular junction in infants with retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmol Retina. 2018;2(9):963-971. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maldonado RS, O’Connell RV, Sarin N, et al. Dynamics of human foveal development after premature birth. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2315-2325. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viehland C, Chen X, Tran-Viet D, et al. Ergonomic handheld OCT angiography probe optimized for pediatric and supine imaging. Biomed Opt Express. 2019;10(5):2623-2638. doi: 10.1364/BOE.10.002623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song S, Zhou K, Xu JJ, Zhang Q, Lyu S, Wang R. Development of a clinical prototype of a miniature hand-held optical coherence tomography probe for prematurity and pediatric ophthalmic imaging. Biomed Opt Express. 2019;10(5):2383-2398. doi: 10.1364/BOE.10.002383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seely KR, Wang KL, Tai V, et al. Auto-processed retinal vessel shadow view images from bedside optical coherence tomography to evaluate plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(9):16. doi: 10.1167/tvst.9.9.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tran-Viet D, Wong BM, Mangalesh S, Maldonado R, Cotten CM, Toth CA. Handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging through the undilated pupil in infants born preterm or with hypoxic injury or hydrocephalus. Retina. 2018;38(8):1588-1594. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangalesh S, McGeehan B, Tai V, et al. Macular OCT characteristics at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age in infants examined for retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmol Retina. Published online September 11, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothman AL, Tran-Viet D, Vajzovic L, et al. Functional outcomes of young infants with and without macular edema. Retina. 2015;35(10):2018-2027. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell JP, Nudleman E, Yang J, et al. Handheld optical coherence tomography angiography and ultra-wide-field optical coherence tomography in retinopathy of prematurity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(9):977-981. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.2481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogel RN, Strampe M, Fagbemi OE, et al. Foveal development in infants treated with bevacizumab or laser photocoagulation for retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):444-452. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moshiri Y, Legocki AT, Zhou K, et al. Handheld swept-source optical coherence tomography with angiography in awake premature neonates. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2019;9(9):1495-1502. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.09.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laws DE, Morton C, Weindling M, Clark D. Systemic effects of screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(5):425-428. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.5.425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke WN, Hodges E, Noel LP, Roberts D, Coneys M. The oculocardiac reflex during ophthalmoscopy in premature infants. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(6):649-651. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)76029-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zores C, Dufour A, Pebayle T, Langlet C, Astruc D, Kuhn P. Very preterm infants can detect small variations in light levels in incubators. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(10):1005-1011. doi: 10.1111/apa.13085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White RD, Smith JA, Shepley MM, Committee to Establish Recommended Standards for Newborn ICUD . Recommended standards for newborn ICU design, eighth edition. J Perinatol. 2013;33 suppl 1:S2-16. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Disher T, Cameron C, Mitra S, Cathcart K, Campbell-Yeo M. Pain-relieving interventions for retinopathy of prematurity: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20180401. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eTable 1. List and description of events collected for optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination during the study

eTable 2. Intra-observer reproducibility results for both the observers for the collection of stress factors in 5 infants with 11 examinations during optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO)

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort and categories of respiratory support used during the optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination for retinopathy of prematurity screening

eTable 4. Occurrence of stress events for optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination

eTable 5. Comparison of studies reporting the impact of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) examinations with imaging modalities versus with the standard binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy examination on infant stress

eFigure. Behavioral and physiologic measures of stress at baseline (within 10 minutes before optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging/binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy (BIO) examination), and during first and second eye OCT imaging/BIO examination