Abstract

Background

Hyperglycemic conditions are associated with respiratory dysfunction. Although several studies have reported that insulin resistance (IR) is related to decreased lung function, the association between IR and change in lung function has been rarely studied. This study aimed to investigate the potential association of IR on annual change in lung function using a community-based prospective cohort in Korea.

Methods

We selected 4827 Korean participants whose serial lung functions were assessed over 4 years using 1:3 propensity score matching. Exposure was baseline IR estimated with homeostatic model assessment (HOMA-IR), and outcomes were annual changes in lung function determined by calculating the regression coefficient using least-square linear regression analysis.

Results

In the multivariate linear regression, per one unit increased log transformed HOMA-IR was associated with decline in FEV1%-predicted (β: − 0.23, 95% CI: − 0.36 to − 0.11) and FVC %-predicted (β: − 0.20, 95% CI: − 0.33 to − 0.08), respectively. In the generalized additive model plot, HOMA-IR showed a negative linear association with annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted. The suggested threshold of HOMA-IR for decline in lung function was 1.0 unit for annual change in FEV1%-predicted and 2.2 unit for annual change in FVC %-predicted. Age showed statistically significant effect modification on the relationship between HOMA-IR and annual change in FEV1%-predicted. Increased HOMA-IR was associated with the decreased annual change in FEV1%-predicted, particularly in older people.

Conclusions

In South Korea, increased HOMA-IR was associated with decline in lung function. Since IR was related to decline in FEV1%-predicted, particularly in older people, tailored approaches are needed in these populations. The potential pulmonary hazard of IR needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12890-021-01478-7.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Lung, Insulin resistance, Spirometry

Background

Diabetes mellitus is a prevalent chronic disease in modern society, with many experiencing diabetes and its complications [1, 2]. Lung function decline has been considered a major complication of diabetes [3–5]. Several studies have found that diabetes and hyperglycemia are associated with the development of various pulmonary diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and interstitial lung disease [6–8]. Therefore, good control of diabetes may prevent future lung diseases.

Increased insulin resistance (IR) has been associated with the future development of obesity, diabetes [9], cardiovascular diseases [10], neurologic impairment [11], and kidney dysfunction [12]. Although several studies have reported the potential association between IR and decreased lung function, none of these studies have evaluated the longitudinal effect of IR on future lung function changes. The aging process can cause diverse physiological, immunological and structural changes in the respiratory system [13, 14]. Thus, analyzing consecutive measurements of lung function may help to interpret the effects of aging on IR and lung function changes. In addition, it can clarify a causal association between IR and lung function.

Since diabetes is associated with future decline in lung function and IR is a fundamental pre-condition of diabetes, we hypothesized that increased IR may be associated with future decline in lung function. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between IR and lung function change using data from a community-based prospective Ansan-Ansung cohort in Korea.

Methods

Participants

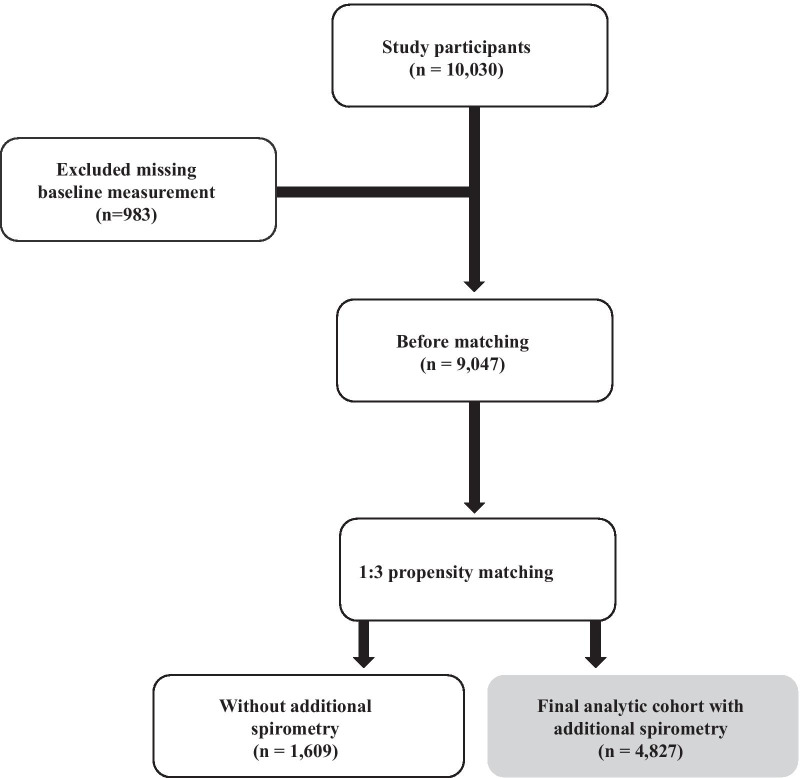

The Ansan-Ansung cohort comprise participants aged 40–69 years who lived in Ansan (urban) and Ansung (rural) areas, and this cohort was analyzed to determine the factors affecting the incidence of chronic diseases. Baseline measurements were performed between May 2001 and February 2003, and two subsequent lung function tests were performed biennially thereafter. More detailed information about the Ansan-Ansung cohort can be obtained in previous reports [15, 16]. Of the 10,030 participants, we excluded 983 missing baseline measurements. Among the 9047 subjects, 4827 subjects with additional spirometry were selected using 1:3 propensity score matching with 1609 subjects without additional spirometry. The differences in clinical characteristics of participants with or without additional spirometry were described in Additional file 3: Table S1. Therefore, 4827 matched participants were finally included in this analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study subject selection

Exposure: IR

IR was assessed using the homeostatic model assessment for IR (HOMA-IR). HOMA-IR was calculated using the following equation: fasting insulin (μIU/mL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/405 [17].

Outcomes: change in lung function

The main outcomes were annual changes in lung function. Lung function tests were performed using a spirometer (VMAX2130; Sensormedics Corporation, Yorba, CA, USA). Pre-bronchodilator values were measured three times by trained technicians, and the best scores were recorded. Predicted values of functional vital capacity (FVC %-predicted) and functional expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1%-predicted) were calculated using the Korean formula [18]. The FEV1/FVC ratio was expressed as the percentage of raw value of FEV1 divided by the raw value of FVC, according to previous literature [19, 20]. Annual changes in FEV1%-predicted, FVC %-predicted, and FEV1/FVC ratio was determined by calculating the regression coefficient using least-square linear regression analysis, with FEV1%-predicted, FVC %-predicted, and FEV1/FVC ratio as functions of time in years. It was applied to all values of FEV1%-predicted, FVC %-predicted, and FEV1/FVC ratio that was obtained during the follow-up period (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Measurements and other definitions

Trained investigators interviewed participants regarding their socioeconomic status and lifestyle habits using Additional file 1: KoGES Baseline Core Questionnaire. High income was defined as the highest quintile of monthly household income (≥ 3 million won a month). Active physical activity was defined as 60 min/day of moderate-intensity activity or 30 min/day of vigorous-intensity activity [21]. Blood pressure (BP) was defined as the average BP on both arms using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer (Baumanometer-Standby; W. A. Baum Co., Inc., Copiague, NY, USA). High BP was defined as systolic BP > 140 mmHg or diastolic BP > 90 mmHg. Body mass index (BMI) was defined by dividing the weight by the square of the height (kg/m2). Waist circumference was measured at the narrowest point between the lower rib and the iliac crest (measured to the nearest 0.1 cm). All blood samples were examined after fasting for at least 8 h. Hemoglobin and white blood cell (WBC) count were analyzed using enzymatic methods with ADVIA 120 (Bayer Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY, USA). Fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), triglyceride, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, C-reactive protein (CRP), and serum creatinine levels were measured using ADVIA 1650 (Siemens, Tarrytown, NY, USA). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was defined using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation [22]. Annual averaged values were obtained for BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic BP, triglyceride, HDL cholesterol, eGFR, WBC count, fasting glucose, HbA1c, hemoglobin, and CRP level.

Statistical analyses

We compared individuals without additional spirometry or with missing values to the rest of participants. Variables that showed significant differences were selected for matching. As a result, age, sex, high income, college graduate, smoking status, active physical activity, baseline values of BMI, systolic BP, diastolic BP, WBC, CRP, and FEV1%-predicted were used in the propensity score matching. The normality of the distribution of continuous variables was assessed using histogram and Q–Q plots. Mean ± standard deviation (SD) was used to express normally distributed continuous variables, whereas median with interquartile range (IQR) was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables. The P-trend was analyzed using linear regression for the normally distributed continuous variables, the Jonckheere–Terpstra test for the non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the Cochran–Armitage test for categorical variables. We further analyzed the difference between individuals with and without additional spirometry using student’s t-test for a normally distributed continuous variable, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variable, and Pearson’s Chi-squared test for categorical variables. The correlation between age and HOMA-IR was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis.

The simple associations between HOMA-IR and spirometric parameters were expressed using the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) function. We performed the linear regression analysis between log-transformed HOMA-IR and annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the lowest quartile of annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted were analyzed using logistic regression analysis.

In multivariate analyses, covariates were chosen based on clinical and statistical relevance. The non-linear association between HOMA-IR and annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted was analyzed using the multivariate generalized additive model (GAM) for Gaussian distributions with the “mgcv” package, and calculation of Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used for the model fitting. In AIC, lower scores within the data set indicate a better model fit [23]. The threshold point of HOMA-IR was chosen based on the best fit determined by AIC among the models.

In the subgroup analysis, all control variables were used, and participants were divided by the median for continuous variable. The modulatory effect was confirmed by adding the interaction term of variables defining the subgroup to the multivariate linear regression analysis. To visualize potential interaction of age on the association between IR and annual change in lung function, the LOWESS regression with interaction was implemented using the “predict3d” package. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (R Core Team 2019; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

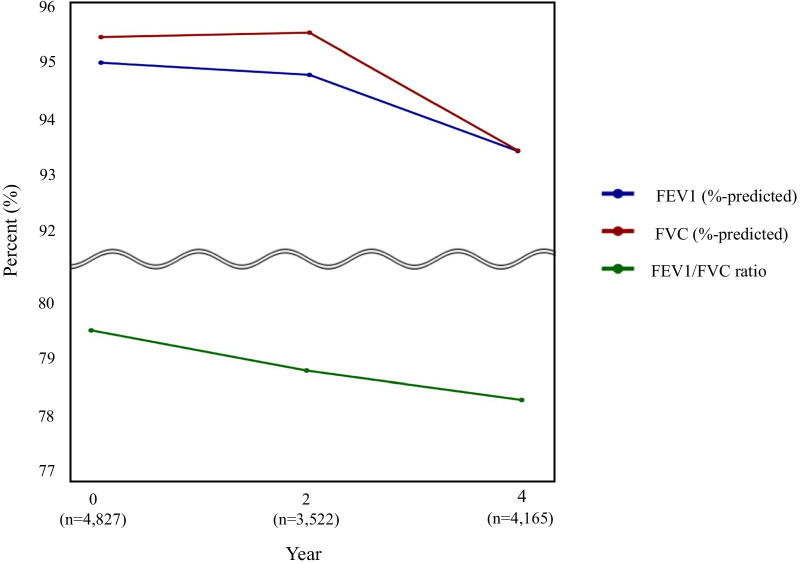

The mean age of the 4827 participants was 52.6 years, 45.3% were men, 48.0% had active physical activity, and 41.7% were current or past smokers. The mean ± SD of annual averaged BMI, systolic and diastolic BP, waist circumference, HDL cholesterol, eGFR, hemoglobin, and WBC count were 24.4 ± 3.0 kg/m2, 119.6 ± 15.6 mmHg, 79.0 ± 9.4 mmHg, 83.2 ± 8.6 cm, 44.9 ± 8.8 mL/dL, 82.9 ± 10.9 mL/min/1.73m2, 13.6 ± 1.4 g/dL, and 6.5 ± 1.5 × 103/μL, respectively. Moreover, the median (IQR) of annual averaged fasting glucose, HbA1c, triglyceride, and CRP level were 88 (83–94) mg/dL, 5.6 (5.3–5.8) %, 130 (97–178) mg/dL, and 0.12 (0.07–0.22) mg/dL, respectively. At baseline, the mean ± SD values of FEV1%-predicted, FVC %-predicted, and FEV1/FVC ratio were 94.9 ± 14.1% predicted, 95.4 ± 13.2% predicted, and 79.5 ± 7.9%, respectively. The mean of FEV1%-predicted, FVC %-predicted, and FEV1/FVC ratio decreased in subsequent lung function measurement (Fig. 2). The mean ± SD values of annual changes in FEV1%-predicted, FVC %-predicted, and FEV1/FVC ratio were − 0.42 ± 2.62%-predicted/year, − 0.49 ± 2.72% predicted/year, and − 0.35 ± 1.56%/year, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Mean lung function trajectories over 4 years. Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity

The clinical characteristics of the study population according to HOMA-IR quartile are shown in Table 1. Although age was not associated with HOMA-IR quartile, the increased HOMA-IR quartile was associated with a decreased proportion of men. The correlation analysis between age and HOMA-IR also was not statistically significant (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). Although income and educational status were not associated with HOMA-IR quartile, the increased HOMA-IR quartile was associated with a decreased rate of active physical activity and current or past smoking. With the increase of HOMA-IR quartile, BMI, systolic and diastolic BP, waist circumference, WBC count, fasting glucose, HbA1c, triglyceride, hemoglobin, and CRP level increased, whereas HDL cholesterol decreased. With the increase of HOMA-IR quartile, baseline FVC %-predicted decreased, but FEV1/FVC increased. Baseline FEV1%-predicted was not associated with HOMA-IR.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population according to HOMA-IR quartile

| HOMA-IR groups (n = 4827) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Q: < 1.05 (n = 1218) | 2Q: 1.05–1.45 (n = 1211) | 3Q: 1.46–2.03 (n = 1191) | 4Q: ≥ 2.04 (n = 1207) | P-trend | |

| Age(years) | 53.06 ± 9.11 | 52.53 ± 8.86 | 52.49 ± 8.84 | 52.50 ± 8.93 | 0.131 |

| Male, n (%) | 649 (53.3) | 551 (45.5)* | 462 (38.8)*† | 524 (43.4)*‡ | < 0.001 |

| High income, n (%) | 161 (13.2) | 170 (14.0) | 160 (13.4) | 182 (15.1) | 0.263 |

| College graduate, n (%) | 119 (9.8) | 129 (10.6) | 119 (10.0) | 127 (10.5) | 0.681 |

| Current or past smoker, n (%) | 582 (47.8) | 494 (40.8)* | 433 (36.4)*† | 506 (41.9)*‡ | < 0.001 |

| Active physical activity, n (%) | 595 (48.8) | 631 (52.1)* | 553 (46.4)† | 536 (44.4)*† | 0.003 |

| Annual averaged BMI (Kg/m2) | 23.32 ± 2.95 | 23.83 ± 2.82* | 24.64 ± 2.75*† | 25.83 ± 3.03*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged systolic BP (mmHg) | 117.72 ± 15.32 | 117.95 ± 15.30 | 119.49 ± 15.09* | 123.44 ± 16.13*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77.65 ± 9.35 | 78.05 ± 9.45 | 79.07 ± 9.17*† | 81.14 ± 9.16*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged waist circumference (cm) | 80.26 ± 8.22 | 81.63 ± 7.97* | 83.78 ± 8.25*† | 87.18 ± 8.22*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 85 (81–90) | 86 (82–91)* | 88 (83–94)*† | 94 (87–109)*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged HbA1c (%) | 5.4 (5.3–5.7) | 5.5 (5.3–5.8) | 5.6 (5.3–5.8)*† | 5.8 (5.5–6.4)*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged triglyceride (mg/dL) | 118 (90–162) | 120 (91–162) | 129 (98–175)*† | 154 (115–210)*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 46.47 ± 9.25 | 45.65 ± 8.91 | 44.73 ± 8.70* | 42.71 ± 8.02*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 83.44 ± 10.98 | 83.40 ± 10.68 | 82.43 ± 10.77*† | 82.15 ± 11.16*† | 0.004 |

| Annual averaged hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.64 ± 1.41 | 13.51 ± 1.42 | 13.45 ± 1.51* | 13.69 ± 1.42†‡ | 0.010 |

| Annual averaged WBC count (× 103/μL) | 6.40 ± 1.55 | 6.34 ± 1.47 | 6.43 ± 1.60 | 6.78 ± 1.52*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Annual averaged CRP level (mg/dL) | 0.10 (0.06–0.20) | 0.10 (0.06–0.20) | 0.12 (0.07–0.21)*† | 0.15(0.08–0.26)*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Baseline FEV1 (L) | 2.84 ± 0.68 | 2.81 ± 0.68 | 2.77 ± 0.68 | 2.78 ± 0.68 | 0.045 |

| Baseline FVC (L) | 3.63 ± 0.86 | 3.57 ± 0.87 | 3.49 ± 0.86* | 3.49 ± 0.86* | < 0.001 |

| Baseline FEV1 (%-predicted) | 94.73 ± 14.46 | 95.26 ± 13.87 | 95.60 ± 14.28 | 94.18 ± 13.57 | 0.071 |

| Baseline FVC (%-predicted) | 96.26 ± 13.19 | 96.27 ± 13.30 | 95.81 ± 13.61 | 93.10 ± 12.33*†‡ | < 0.001 |

| Baseline FEV1/FVC (%) | 78.68 ± 8.59 | 79.33 ± 7.90 | 79.76 ± 7.82* | 80.06 ± 7.28* | < 0.001 |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed variables and percentage for categorical variables. P-trend was analyzed normally distributed continuous variables by the linear regression, for non-normally distributed continuous variable by Jonckheere-Terpstra tests, and for categorical variables by Cochran-Armitage test for trend

*, †, and ‡ meant P < 0.05 when compared to < 1.05, 1.06–1.45, 1.45–2.03 groups of HOMA-IR, respectively, using Bonferroni post-hoc analysis of one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed continuous variable, and Chi-square tests for categorical variables

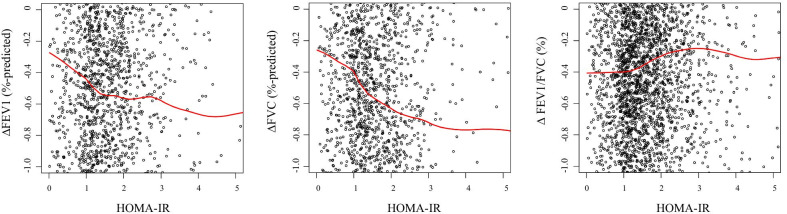

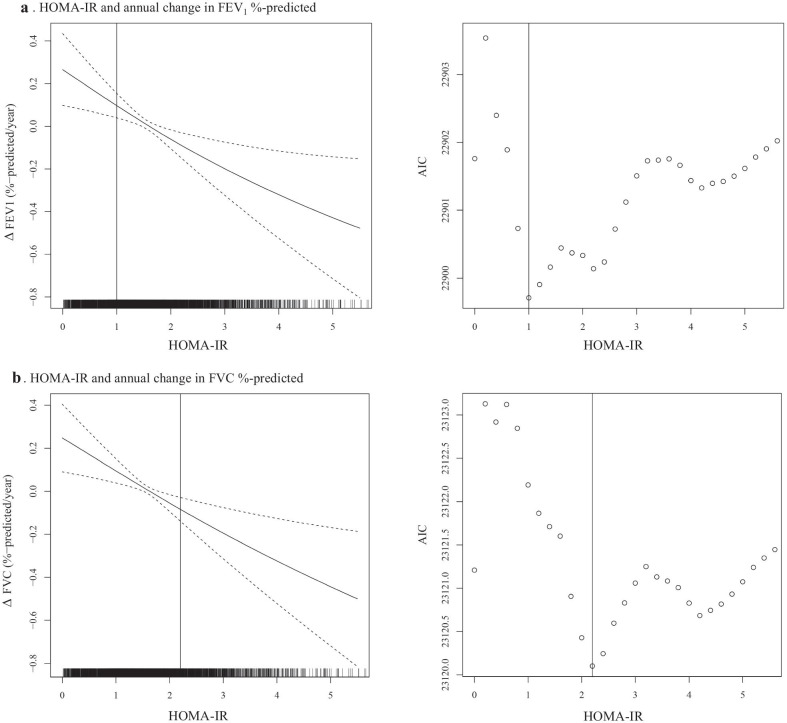

We explored the association between HOMA-IR and annual changes in lung function (Fig. 3). As HOMA-IR increased, annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted change decreased, whereas annual change in FEV1/FVC ratio change increased. In multivariate linear regression analysis, per one unit increased log transformed HOMA-IR was associated with decline in FEV1%-predicted (β: − 0.23, 95% CI: − 0.36 to − 0.11, p < 0.001) and FVC %-predicted (β: − 0.20, 95% CI: − 0.33 to − 0.08, p = 0.001) (Table 2). In the categorical analysis, the odds for the lowest quartile of annual changes in FEV1%-predicted (Q1: < − 1.73%-predicted/year) and FVC %-predicted (Q1: − 1.90%-predicted/year) showed increasing trend (P-trend < 0.001) as quartiles of HOMA-IR were increased. The OR of HOMA-IR for lowest quartile of annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted were significantly higher in the upper quartiles compared to the lower quartile. In the multivariate GAM plot analysis, we identified that the association between HOMA-IR and annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted were negative linear, and the lowest AICs were found in HOMA-IR 1.0 unit for annual change in FEV1%-predicted and 2.2 unit for annual change in FVC %-predicted (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The association between HOMA-IR and annual changes in lung function. The red line represented the LOWESS regression curve. Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; LOWESS, locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing

Table 2.

The effects of HOMA-IR on the lung function change

| Exposure | Outcome: Annual lung function change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆ FEV1 (%-predicted/year) | ∆ FVC (%-predicted/year) | |||

| Log transformed HOMA-IR | Beta (95% CI, P) | Beta (95% CI, P)) | ||

| Per one unit increase (n = 4827) | − 0.23 (− 0.36 to − 0.11, < 0.001) | − 0.20 (− 0.33 to − 0.08, 0.001) | ||

| HOMA-IR quartile | Lowest quartile (Q1) of ∆ FEV1: < − 1.73%-predicted/year | P-trend | Lowest quartile (Q1) of ∆ FVC: < − 1.90%-predicted/year | P-trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, P) | Adjusted OR (95% CI, P) | |||

| 1Q: < 1.05 (n = 1218) | 1 (reference) | < 0.001 | 1 (reference) | < 0.001 |

| 2Q: 1.05–1.44 (n = 1211) | 1.14 (0.94–1.39, 0.191) | 1.15 (0.94–1.41, 0.162) | ||

| 3Q: 1.45–2.02 (n = 1191) | 1.22 (1.00–1.48, 0.055) | 1.30 (1.06–1.59, 0.012) | ||

| 4Q: ≥ 2.03 (n = 1207) | 1.34 (1.09–1.66, 0.006) | 1.38 (1.11–1.71, 0.004) |

The rapid decline in lung function was defined in two aspects, which were the first quartile of FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted, respectively. ORs were adjusted for age, sex, college graduate, high income, smoking status, active physical activity, and annual averaged values of BMI, systolic and diastolic BP, waist circumference, fasting glucose, HbA1c, triglyceride, HDL cholesterol, eGFR, WBC count, hemoglobin, and CRP level. P-trend for HOMA-IR quartile was analyzed by Cochran-Armitage test for trend

Fig. 4.

GAM plot between HOMA-IR and annual changes in lung function. The dashed lines indicate 95% CIs for values of smoothed annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted, using the multivariate GAM analysis after adjusting for age, sex, high income, college graduate, active physical activity, smoking status, and annual averaged values of BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic BP, triglyceride, HDL cholesterol, eGFR, WBC count, hemoglobin, and CRP level. Abbreviations: GAM, general additive model; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high density lipoprotein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; WBC, white blood cell; CRP, C-reactive protein

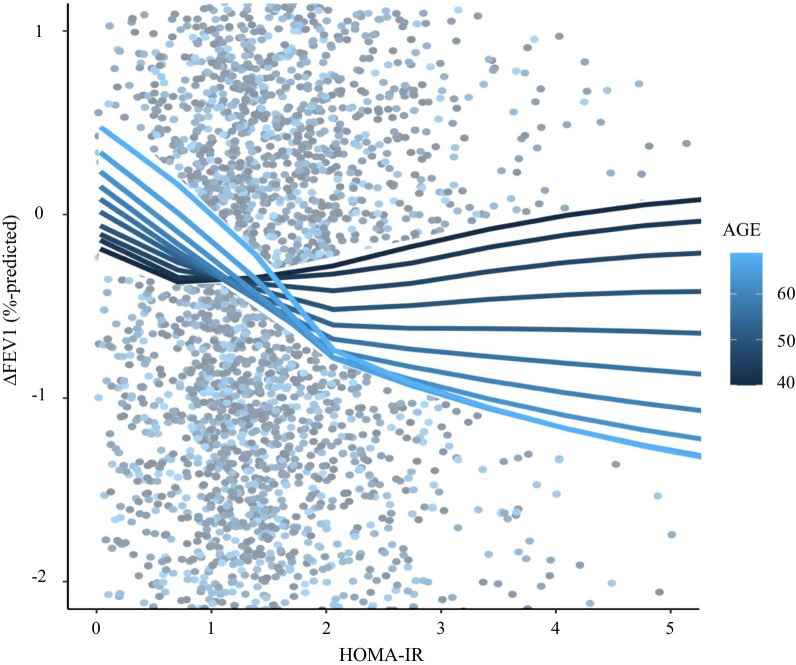

There were no subgroups showing the effect modification between HOMA-IR and annual changes in FVC % predicted (Additional file 3: Table S3). However, participant age significantly modified the effect of HOMA-IR on annual change in FEV1%-predicted (p for interaction = 0.003). Although HOMA-IR was not associated with annual change in FEV1%-predicted in people aged < 50 years, increased HOMA-IR was significantly associated with the decreased annual change in FEV1%-predicted in individuals aged ≥ 50 years (Table 3). We also identified similar effect modification of age on the association between HOMA-IR and annual change in FEV1%-predicted in the LOWESS regression plot with interaction (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis for the effects of HOMA-IR on annual change in lung function

| Exposure: per one unit increase log-transformed HOMA-IR | Adjusted beta (CI, P-value) | Outcome: annual change in lung function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆ FEV1 (%-predicted/year) | ∆ FVC (%-predicted/year) | ||||

| P for interaction | Adjusted beta (CI, P-value) | P for interaction | |||

| Subgroup | No. of people | ||||

| Age (years) | < 50 (n = 2177) | 0.04 (− 0.13 to 0.22, 0.613) | 0.003 | 0.03 (− 0.15 to 0.20, 0.775) | 0.153 |

| ≥ 50 (n = 2650) | − 0.41 (− 0.58 to − 0.24, < 0.001) | − 0.33 (− 0.51 to − 0.16, < 0.001) | |||

| Sex | Male (n = 2186) | − 0.24 (− 0.41 to − 0.07, 0.006) | 0.798 | − 0.15 (− 0.33 to 0.03, 0.103) | 0.554 |

| Female (n = 2641) | − 0.22 (− 0.40 to − 0.05, 0.012) | − 0.24 (− 0.41 to − 0.06, 0.008) | |||

| Current or past smoker | No (n = 2812) | − 0.18 (− 0.34 to − 0.02, 0.027) | 0.447 | − 0.18 (− 0.34 to − 0.02, 0.012) | 0.941 |

| Yes (n = 2015) | − 0.30 (− 0.48 to − 0.11, 0.002) | − 0.18 (− 0.37 to 0.01, 0.060) | |||

| Active physical activity | No (n = 2512) | − 0.17 (− 0.32 to − 0.02, 0.028) | 0.496 | − 0.12 (− 0.28 to 0.04, 0.002) | 0.423 |

| Yes (n = 2315) | − 0.31 (− 0.50 to − 0.11, 0.002) | − 0.29 (− 0.49 to − 0.10, 0.004) | |||

| High BP | No (n = 4043) | − 0.21 (− 0.35 to − 0.08, 0.002) | 0.579 | − 0.20 (− 0.33 to − 0.06, 0.004) | 0.919 |

| Yes (n = 784) | − 0.35 (− 0.66 to − 0.03, 0.030) | − 0.27 (− 0.60 to 0.06, 0.104) | |||

| Annual averaged BMI (kg/m2) | < 24 (n = 2223) | − 0.30 (− 0.50 to − 0.11, 0.002) | 0.345 | − 0.22 (− 0.42 to − 0.03, 0.023) | 0.998 |

| ≥ 24 (n = 2604) | − 0.17 (− 0.33 to − 0.02, 0.031) | − 0.19 (− 0.35 to − 0.02, 0.026) | |||

| Annual averaged eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | < 84 (n = 2496) | − 0.22 (− 0.39 to − 0.05, 0.010) | 0.387 | − 0.10 (− 0.27 to 0.07, 0.256) | 0.751 |

| ≥ 84 (n = 2331) | − 0.24 (− 0.42 to − 0.06, 0.010) | − 0.31 (− 0.49 to − 0.12, 0.001) | |||

| Annual averaged WBC count (× 103/μL) | < 6.3 (n = 2396) | − 0.26 (− 0.44 to − 0.08, 0.006) | 0.643 | − 0.15 (− 0.34 to 0.04, 0.121) | 0.735 |

| ≥ 6.3 (n = 2431) | − 0.21 (− 0.37 to − 0.05, 0.012) | − 0.22 (− 0.40 to − 0.05, 0.013) | |||

| Annual averaged Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | < 13.5 (n = 2462) | − 0.17 (− 0.35 to 0.02, 0.080) | 0.713 | − 0.12 (− 0.31 to 0.07, 0.217) | 0.425 |

| ≥ 13.5 (n = 2365) | − 0.29 (− 0.45 to − 0.14, < 0.001) | − 0.24 (− 0.40 to − 0.08, 0.004) | |||

Adjusted beta and 95% CIs were analyzed using the multivariate linear regression. Age, sex, college graduate, high income, smoking status, active physical activity, and annual averaged values of BMI, systolic and diastolic BP, waist circumference, fasting glucose, HbA1c, triglyceride, HDL cholesterol, eGFR, WBC count, hemoglobin, and CRP level were included for adjustment. The variable used to divide subgroup was excluded from this analysis

Fig. 5.

LOWESS regression plot with interaction for the effect modification of age on the association between HOMA-IR and annual change in FEV1%-predicted. Solid lines represented the univariate LOWESS regression curves modulated by age. The darkest blue, and lightest blue lines represented lines of mean minus one SD (44 years) and plus one SD (62 years). Abbreviations: LOWESS, locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; SD, standard deviation

Discussion

Our study revealed that increased IR associated with decline in lung function using community-based prospective cohort in Korea. Recently, decreased lung function has been suggested as a complication of IR. In their large-scale cross-sectional study, Lawlor et al. found that HOMA-IR decreased by 5% and 8% for a 1 SD increase in log FEV1 and FVC, respectively [24]. Sagun et al. also showed that decreased FEV1%-predicted was correlated with increased insulin resistance (HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5) in an age-adjusted analysis (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.94–1.00, P = 0.028) [25]. However, most previous studies were cross-sectional, and a causal association between insulin resistance and decreased lung function needed to be evaluated in a prospective cohort. Therefore, we conducted the current study using a prospective community-based cohort and found that increased insulin resistance was associated with a decline in lung function, particularly in the elderly population.

In the current study, increased HOMA-IR was independently associated with decline in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted. Cigarette smoking is a well-established risk factor for lung function deterioration. In the large scale randomized clinical trial, annual change in FEV1%-predicted was approximately − 1.4%-predicted/year in the continuing smoker group [26]. Compared to this result, IR can be considered a risk factor for rapid decline in lung function. In LOWESS regression analysis, increased HOMA-IR presented negative association with annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted, but not with FEV1/FVC ratio. In the natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the rate of FEV1 decline is slow at high FEV1 and faster as FEV1 decreases [27]. Due to the nature of the community-based cohort, the majority of participants had a high baseline FEV1. These factors could explain why HOMA-IR was not associated with annual change in FEV1/FVC ratio.

We also found negative linear associations between HOMA-IR and annual changes in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted using the multivariate GAM plot, and the suggested threshold of HOMA-IR for decline in lung function was 1.0 unit for annual change in FEV1%-predicted and 2.2 unit for annual change in FVC %-predicted. As a surrogate marker of IR, several studies have shown that the cutoff value of HOMA-IR for the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in the Korean population is approximately 2.5 [28–30]. Our findings showed lower threshold than those of previous studies, indicating that decline in lung function may be more sensitive to the systemic effects of IR. Moreover, these results suggest that early treatment of IR can be an effective intervention to prevent decline in lung function.

There were two possible explanations for the potential pulmonary hazard of IR. First, chronic low-grade inflammation in adipose tissue contributes to the development of IR [31, 32]. Levels of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6, are increased with IR and cause lung fibrosis and inflammation [33, 34]. Second, respiratory muscle weakness is related to IR. In high IR status, TNF-α and interferon-gamma cause muscle wasting through the degeneration of myotubes and modulation of myogenesis [35, 36].

In subgroup analysis, age showed a statistically significant effect modification on the association between HOMA-IR and annual change in FEV1%-predicted. Although HOMA-IR was not associated with annual change in FEV1%-predicted in the younger group, increased HOMA-IR was significantly related to decline in FEV1%-predicted in the older group.

IR is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation [31]. The risk of chronic low-grade inflammation increased with the aging process [37, 38]. Lung function can decline with increased inflammation [39, 40]. Therefore, we assumed that increased chronic low-grade inflammation during the aging process may potentiate the metabolic hazard of IR in lung function deterioration. In this regard, early intervention to reduce IR in the elderly population may have a beneficial effect on future lung function preservation.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, two or fewer additional lung function measurements were performed in this study. Therefore, our study period was not sufficiently long. Further studies performing more spirometric tests will be needed to clarify the long-term effect of IR on decline in lung function. Second, our study was conducted in single ethnicity and selected areas. Therefore, the results should be elucidated cautiously in accordance with racial and regional differences.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between IR and lung function using a large-scale prospective cohort based on the general population. Second, we calculated the threshold of HOMA-IR for decline in lung function using a nonlinear analytic method. Finally, the interaction between age and IR to annual change in FEV1%-predicted was investigated and presented using visualization.

Conclusion

In South Korea, increased IR was independently associated with decline in FEV1%-predicted and FVC %-predicted. We also found that age modified the relationship between IR and FEV1%-predicted, particularly valid in older people. The potential pulmonary hazard of IR needs to be confirmed in future interventional studies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. KoGES baseline Core Questionnaire.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Definitions of outcome and exposure variables. Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance. Figure S2. Correlation between age and HOMA-IR. Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance.

Additional file 3: Tables S1. Comparison of participants' baseline characteristics with or without additional spirometry and Table S2. Additional subgroup analysis for the effects of HOMA-IR on annual change in lung function.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the NRF for funding to conduct Ansan-Ansung cohort (Grant No: NRF-2019R1G1A1099753). We also thank all participants and staffs of the Ansan-Ansung cohort.

Abbreviations

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC

Functional vital capacity

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- BP

Blood pressure

- BMI

Body mass index

- WBC

White blood cell

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- SD

Standard deviation

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LOWESS

Locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing

- GAM

Generalized additive model

- AIC

Akaike’s information criterion

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Authors' contributions

S.W.L. conceptualization. S.H.K. data curation/formal analysis. H.S.K. investigation/ methodology. S.H.K. writing – original draft. H.K.M. and H.S.K. writing – review and editing. S.W.L. supervision/validation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MIST) (Grant No: NRF-2019R1G1A1099753). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, data curation and analysis, or drafting of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data of our study is fully available when manuscript is accepted for publication.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Using the Ansan-Ansung cohort, this study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review boards of the Nowon Eulji Medical Center, Eulji University approved the protocol and ethics of the study (Approval Number: 2019-06-014). Participants provided written informed consent, and all data were completely anonymized prior to access.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sang Hyuk Kim and Hyun Sam Kim have contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Susan D, Beulens JW, Yvonne T. van der S, Grobbee DE, Nealb B: The global burden of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17(1_suppl):s3–s8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000368191.86614.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein O, Krishnan J, Glick S, Smith LJ. Systematic review of the association between lung function and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2010;27(9):977–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh H-C, Punjabi NM, Wang N-Y, Pankow JS, Duncan BB, Cox CE, Selvin E, Brancati FL. Cross-sectional and prospective study of lung function in adults with type 2 diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):741–746. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khateeb J, Fuchs E, Khamaisi M. Diabetes and lung disease: a neglected relationship. Rev Diabetic Stud RDS. 2019;15:1. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2019.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamillapalli C, Tentu R, Jain NK, Bhandari R. COPD and type 2 diabetes. Curr Respir Med Rev. 2019;15(2):112–119. doi: 10.2174/1573398X15666190211155640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enomoto T, Usuki J, Azuma A, Nakagawa T, Kudoh S. Diabetes mellitus may increase risk for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2003;123(6):2007–2011. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.6.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez MK, Piedimonte G. Metabolic asthma: is there a link between obesity, diabetes, and asthma? Immunol Allergy Clin. 2014;34(4):777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D, Karnieli E. The metabolic syndrome—from insulin resistance to obesity and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):559–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginsberg HN. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Investig. 2000;106(4):453–458. doi: 10.1172/JCI10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim B, Feldman EL. Insulin resistance in the nervous system. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(3):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Cosmo S, Menzaghi C, Prudente S, Trischitta V. Role of insulin resistance in kidney dysfunction: insights into the mechanism and epidemiological evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(1):29–36. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma G, Goodwin J. Effect of aging on respiratory system physiology and immunology. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(3):253. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skloot GS. The effects of aging on lung structure and function. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33(4):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y, Han B-G, Group K Cohort profile: the Korean genome and epidemiology study (KoGES) consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):e20–e20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo A, Lee SW, Koh HY, Kim MA, Han MY, Yon DK. Incidence of cancer after asthma development: 2 independent population-based cohort studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2005;58(3):230–242. doi: 10.4046/trd.2005.58.3.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Global Strategy for Asthma Prevention and Treatment. 2020 Update, https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/GINA-2020-report_20_06_04-1-wms.pdf.

- 20.Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Frith P, Halpin DM, Han M: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. European Respiratory Journal 2019, 53(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Yang YJ. An overview of current physical activity recommendations in primary care. Korean J Fam Med. 2019;40(3):135–142. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.19.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang Y, Castro AF, III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson D, Burnham K. Model selection and multi-model inference. Second NY: Springer-Verlag. 2020;2004(63):10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawlor D, Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Associations of measures of lung function with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Diabetologia. 2004;47(2):195–203. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagun G, Gedik C, Ekiz E, Karagoz E, Takir M, Oguz A. The relation between insulin resistance and lung function: a cross sectional study. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0125-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Murray RP. Smoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(5):675–679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vestbo J, Lange P. Natural history of COPD: Focusing on change in FEV1. Respirology (Carlton, Vic) 2016;21(1):34–43. doi: 10.1111/resp.12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim B, Choi HY, Kim W, Ahn C, Lee J, Kim JG, Kim J, Shin H, Yu JM, Moon S. The cut-off values of surrogate measures for insulin resistance in the Korean population according to the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KOGES) PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0206994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun K-J, Han K, Kim MK, Park Y-M, Baek K-H, Song K-H, Kwon H-S. Insulin resistance distribution and cut-off value in Koreans from the 2008–2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baek JH, Kim H, Kim KY, Jung J. Insulin resistance and the risk of diabetes and dysglycemia in Korean general adult population. Diabetes Metab J. 2018;42(4):296–307. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2017.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Luca C, Olefsky JM. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zatterale F, Longo M, Naderi J, Raciti GA, Desiderio A, Miele C, Beguinot F. Chronic adipose tissue inflammation linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Front Physiol. 2020;10:1607–1607. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundblad LK, Thompson-Figueroa J, Leclair T, Sullivan MJ, Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Tumor necrosis factor–α overexpression in lung disease: a single cause behind a complex phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(12):1363–1370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1349OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rincon M, Irvin CG. Role of IL-6 in asthma and other inflammatory pulmonary diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(9):1281. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laghi F, Tobin MJ. Disorders of the respiratory muscles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(1):10–48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2206020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Londhe P, Davie JK. Gamma interferon modulates myogenesis through the major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator, CIITA. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(14):2854–2866. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05397-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fagiolo U, Cossarizza A, Scala E, Fanales-Belasio E, Ortolani C, Cozzi E, Monti D, Franceschi C, Paganelli R. Increased cytokine production in mononuclear cells of healthy elderly people. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(9):2375–2378. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krabbe KS, Pedersen M, Bruunsgaard H. Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39(5):687–699. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang R, Burke GL, Enright PL, Newman AB, Margolis HG, Cushman M, Tracy RP, Wang Y, Kronmal RA, Barr RG. Inflammatory markers and longitudinal lung function decline in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):602–610. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hancox RJ, Poulton R, Greene JM, Filsell S, McLachlan CR, Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Williams MJ, Williamson A, Sears MR. Systemic inflammation and lung function in young adults. Thorax. 2007;62(12):1064–1068. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.076877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. KoGES baseline Core Questionnaire.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Definitions of outcome and exposure variables. Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance. Figure S2. Correlation between age and HOMA-IR. Abbreviations: HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance.

Additional file 3: Tables S1. Comparison of participants' baseline characteristics with or without additional spirometry and Table S2. Additional subgroup analysis for the effects of HOMA-IR on annual change in lung function.

Data Availability Statement

The data of our study is fully available when manuscript is accepted for publication.