Abstract

With more time being spent on caregiving responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, female scientists’ productivity dropped. When female scientists conduct research, identity factors are better incorporated in research content. In order to mitigate damage to the research enterprise, funding agencies can play a role by putting in place gender equity policies that support all applicants and ensure research quality. A national health research funder implemented gender policy changes that included extending deadlines and factoring sex and gender into COVID-19 grant requirements. Following these changes, the funder received more applications from female scientists, awarded a greater proportion of grants to female compared to male scientists, and received and funded more grant applications that considered sex and gender in the content of COVID-19 research. Further work is urgently required to address inequities associated with identity characteristics beyond gender.

Keywords: gender policy, female scientists, funding agency

The COVID-19 pandemic is exposing and exacerbating gender biases in science, calling on funders to play an active role in finding solutions. During the months in which COVID-19 measures required people to stay home, scientists with feminine-coded names submitted substantially fewer manuscripts than scientists with masculine-coded names, especially manuscripts about severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and COVID-19 (1–3). Such findings may be partly explained by the heavier teaching, service, and caregiving loads borne by White women and people of color in academia (3–5). Researchers belonging to minoritized groups who are overrepresented among COVID-19 cases and deaths, such as racial and ethnic minorities, Indigenous Peoples, and disabled people (6–8), may also be shouldering additional responsibilities to students, families, communities, or their own health (9).

As a consequence of the pandemic, researchers facing time constraints may be less able to pivot and contribute their expertise to COVID-19 research opportunities being rolled out by funding agencies worldwide. In addition to concerns about fairness, such inequities matter because funding female scientists is more likely to yield health research that appropriately accounts for sex and gender (10, 11). Similarly, funding Black scientists is more likely to result in health research that serves the needs of Black people (12). Failing to equitably fund researchers across groups may therefore mean short-changing the communities to which they belong and which they may be better equipped to study in nuanced, expert ways.

In February 2020, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) launched a rapid response COVID-19 funding competition. Compared to historical patterns, fewer female scientists applied for funding, success rates were lower among women who applied, and a smaller proportion of grants accounted for sex and gender in the research content. To address these issues, CIHR implemented a series of data-driven gender policy interventions in a second COVID-19 funding competition in April to May 2020. To expand the applicant pool, CIHR increased the application intake window from 8 d to 19 d and allowed submission of abridged biosketches rather than requiring the use of the longer online Canadian Common CV. To increase research quality, CIHR created a guidance document titled, “Why sex and gender need to be considered in COVID-19 research” (13) and required reviewers to evaluate the integration of sex, gender, and other identity factors (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, culture, religion, geography, education, disability, income, and sexual orientation) at all stages of the research process.

Results

The first competition funded 100 of 227 applications (overall success rate 44%). The second competition garnered greater application pressure, funding 139 of 1,488 applications (overall success rate 9%). From the first to second COVID competition, the proportion of applications submitted by principal investigators (PIs) who self-identified as female increased from 29 to 39%, and the proportion of successful applications with a female PI doubled from 22 to 45% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Female application pressure and success rates before and after gender policy changes to the roll out of two COVID-19 funding opportunities

| Proportion of total applications submitted, % | Proportion of applications funded, % | |||

| Female PI | Male PI | Female PI | Male PI | |

| Investigator-initiated open competition | 36 (n = 790) | 64 (n = 1392) | 40 (n = 154) | 60 (n = 231) |

| First COVID-19 competition | 29 (n = 65) | 70 (n = 159) | 22 (n = 22) | 76 (n = 76) |

| Second COVID-19 competition | 39 (n = 586) | 60 (n = 898) | 45 (n = 62) | 55 (n = 77) |

Percentages do not always add up to 100, as ≤2% of applicants for each competition did not provide an entry in the female/male field.

PIs who self-identified as being part of a visible minority community were 30% of applicants in both COVID competitions, and 28% and 26% of funded investigators in the first and second competitions, respectively (14). The numbers of applicants who identified as Indigenous, having a disability, gender fluid, nonbinary, or Two-Spirit were too low (counts under five in submitted applications, funded applications, or both) to report in a disaggregated way.

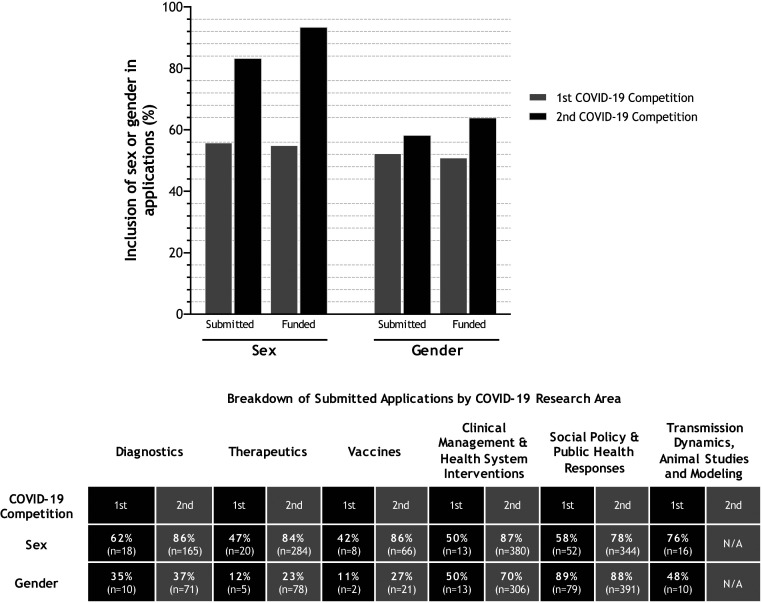

Biological sex factored into 55% and 94% of funded applications in the first and second competitions, respectively (Fig. 1). In the second competition, applications indicating that sex was considered in the proposed work were more likely to be funded (odds ratio [OR] 3.13, 95% CI 1.57 to 6.23). This was not the case in the first competition (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.88).

Fig. 1.

Integration of sex and gender within the research content of COVID-19 grant applications. Proportion of submitted and funded applications that addressed sex or gender considerations in the content of COVID-19 grant proposals during the first and second competitions. A breakdown of the submitted grants by COVID-19 research area is provided under the graph.

Discussion

By analyzing data before and after gender policy interventions implemented within COVID-19 rapid response funding, CIHR demonstrates ways to monitor and potentially redress inequities exacerbated by the pandemic. Offering compensation for dependent caregiver costs, extending early career status, doubling parental leave credits, and allowing for an optional COVID-19 impact statement to be submitted with grants are additional interventions that were applied. Gender policy interventions are an important step toward better and fairer systems. We share four observations.

First, quality should not be sacrificed for speed. In the rush to launch the first COVID-19 funding opportunity in February 2020, short timelines may have created a disadvantage for individuals with caregiving, community, teaching, or self-care responsibilities. Allowing more time in the second competition in April and May 2020 facilitated more applications, despite disruptions to applicants’ laboratories and lives. Although the differences seen are observational and might be attributable to factors other than the gender policy interventions that were implemented, there is reason to believe that extra time can lead to improvements in the number of female applicants and the success of their applications.

Second, implementing changes after discovering a problem is good, but it would be better to prevent problems in the first place. Because of the imbalance between male and female PIs in the first competition, the overall balance across both competitions remains out of proportion compared to historical funding patterns. This may show up in productivity differences in the years to come and will need to be accounted for in evaluations of researchers.

Third, the changes implemented by CIHR appeared to primarily solve problems related to applicants’ sex and gender. Barriers related to other identity dimensions (race and ethnicity, Indigenous identity, disability) require further analysis and consultation to identify solutions. Doing so is crucial to ensure that publicly funded research is allocated fairly and in a way that equitably serves all.

Fourth, educational support and explicit evaluation criteria related to sex, gender, and other identity characteristics may help ensure that applicants and peer reviewers attend to these factors within the proposed research, thereby expanding definitions of research excellence. Such methodological rigor promotes high-quality, relevant, and impactful science that benefits everyone (15).

Materials and Methods

We compared two outcomes. First, we examined application and success rates for grants submitted by PIs with different identity characteristics. Second, we examined whether PIs indicated that their grants accounted for sex and gender, in the web-based application form. We used grants management data routinely collected when applicants and peer reviewers create accounts in the online CIHR system and self-identify as female or male, or do not provide an entry in that field. These data were available for 100% of PIs in this study across both competitions and therefore constituted the primary data for our analyses. Additional data on self-reported gender (woman; man; gender fluid, nonbinary, and/or Two-Spirit) and whether or not the person identifies as an Indigenous person (First Nations, Métis, or Inuit), as a member of a visible minority group, or as a person with a disability were collected from a new self-identity form introduced by CIHR in 2018. The form includes the option, “I prefer not to answer,” for all questions. We compared data from the two COVID competitions to data from the most recent cycle of CIHR’s largest investigator-initiated open competition, as a reference point. We conducted descriptive statistics and logistic regressions to determine the effect of integrating sex and gender on the receipt of a grant, with SPSS, version 26.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the CIHR or the Government of Canada. Data were held internally and analyzed by staff at the CIHR within their mandate as a national funding agency. Research and analytical studies at the CIHR fall under the Canadian Tri-Council policy statement 2: Ethical conduct for research involving humans (16). This study had the objective of evaluating CIHR’s investigator-initiated programs, and thus fell under Article 2.5 of TCPS-2 and not within the scope of Research Ethics Board review in Canada, so was deemed exempt. Nevertheless, applicants were informed, through ResearchNet, in advance of peer review, that CIHR would be evaluating its own processes. All applicants provided their electronic consent; no applicant refused to provide consent.

Acknowledgments

This study was unfunded. Tammy Clifford, Adrian Mota, Sarah Viehbeck, and their teams at CIHR helped implement the interventions, extracted the data, and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: H.O.W. holds a funded grant as principal investigator from the second competition described in the paper. J.H. is employed by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Gender and Health. C.T. is a Scientific Institute director at Canadian Institutes of Health Research and is therefore partially employed by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Data Availability.

The data are housed at CIHR, due to privacy concerns for applicants. Researchers interested in addressing research questions related to grant funding may contact CIHR at Funding-Analytics@cihr-irsc.gc.ca. Additional analyses may be found at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.26.355206.

References

- 1.Vincent-Lamarre P., Sugimoto C., Larivière V., The decline of women’s research production during the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/decline-women-scientist-research-publishing-production-coronavirus-pandemic. Accessed 26 September 2020.

- 2.Andersen J. P., Nielsen M. W., Simone N. L., Lewiss R. E., Jagsi R., COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. eLife 9, e58807 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinho-Gomes A. C., et al., Where are the women? Gender inequalities in COVID-19 research authorship. BMJ Glob. Health 5, e002922 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gewin V., The time tax put on scientists of colour. Nature 583, 479–481 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarino C. M., Borden V. M. H., Faculty service loads and gender: Are women taking care of the academic family? Res. High. Educ. 58, 672–694 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhala N., Curry G., Martineau A. R., Agyemang C., Bhopal R., Sharpening the global focus on ethnicity and race in the time of COVID-19. Lancet 395, 1673–1676 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb Hooper M., Nápoles A. M., Pérez-Stable E. J., COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA 323, 2466–2467 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putz C., Ainslie D., Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by disability status, England and Wales - Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbydisabilitystatusenglandandwales/2marchto14july2020. Accessed 26 September 2020.

- 9.Sabatello M., Burke T. B., McDonald K. E., Appelbaum P. S., Disability, ethics, and health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Public Health 110, 1523–1527 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugimoto C. R., Ahn Y. Y., Smith E., Macaluso B., Larivière V., Factors affecting sex-related reporting in medical research: A cross-disciplinary bibliometric analysis. Lancet 393, 550–559 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen M. W., Bloch C. W., Schiebinger L., Making gender diversity work for scientific discovery and innovation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 726–734 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppe T. A., et al., Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw7238 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Government of Canada , Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Why sex and gender need to be considered in COVID-19 research. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51939.html. Accessed 26 September 2020.

- 14.Witteman H. O., Haverfield J., Tannenbaum C., Positive outcomes of COVID-19 research-related gender policy changes. 10.1101/2020.10.26.355206. Accessed 27 October 2020. [DOI]

- 15.Tannenbaum C., Ellis R. P., Eyssel F., Zou J., Schiebinger L., Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature 575, 137–146 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panel on Research Ethics , Tri-Council policy statement TCPS 2 (2018): Ethical conduct for research involving humans. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique_tcps2-eptc2_2018.html. Accessed 21 January 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are housed at CIHR, due to privacy concerns for applicants. Researchers interested in addressing research questions related to grant funding may contact CIHR at Funding-Analytics@cihr-irsc.gc.ca. Additional analyses may be found at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.26.355206.