Clinical History and Imaging

The patient referred to the neurosurgeon in October 2015, complaining polyuria, polydipsia and polyphagia, associated with violent headache, unresponsive to anti‐inflammatory therapy, vomit and loss of consciousness. After the onset of visual impairment in the left eye, the patient underwent MRI scan that revealed a giant irregular suprasellar mass (max diam 3.5 cm) moving from the level of the infundibular area within the third ventricle chamber; these lesion showed (Figure 1A) strong and in‐homogenous enhancement post‐GAD and little calcified spots were noted within its bulk. Pituitary hormonal levels were within the normal range. In May 2016 the patient underwent surgery, by mean of endoscopic endonasal approach: at this time, due to the hard consistency, the tight adherences of the tumor and the narrow and deep corridor lesion has been only partially removed. As per protocol a second transcranial approach was scheduled, nevertheless three months later, hydrocephalus developed and urgent ventricle‐peritoneal shunt procedure was required, although residual tumor was stable. Six months thereafter a new MRI disclosed a slight enlargement of tumor (volume increase was 30% more than the prior exam), so that transcranial transcortical‐transventricular approach was adopted to remove the lesion. Extent of removal at that time was near‐total (>90%), nevertheless, patient died few weeks later due to severe meningitis that complicated with multi‐organ failure.

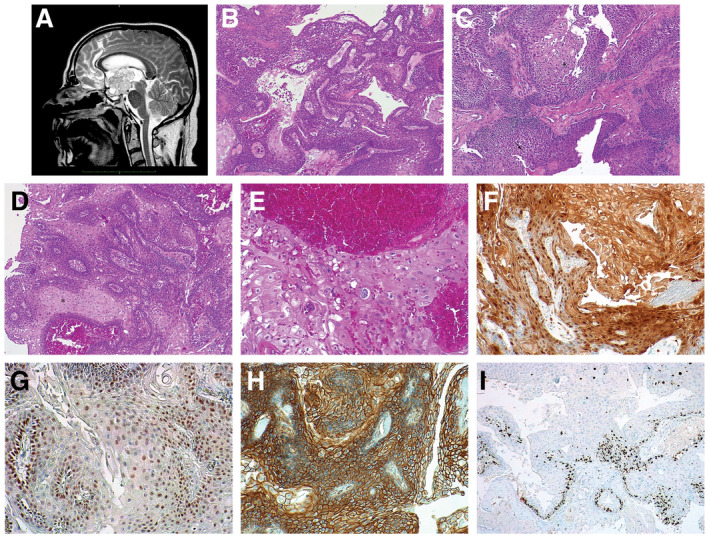

Figure 1.

Pathological Findings

Microscopic examination of the first surgical sample revealed a neoplasm characterized by solid growth of squamous epithelium with pseudopapillary pattern (Figure 1B), with vague peripheral palisading and in absence of wet keratinization, calcification and cholesterol accumulation. Pseudopapillary architecture was created by the presence, within the solid lesion, of clefts surrounded by apoptotic cells (Figure 1C, arrow). Many small whorls were often present (Figure 1C*). Mild atypia was observed (Figure 1D*).

In the second surgical sample, the neoplasm showed similar morphological features in addition to more severe atypia and evident HPV‐like dysplastic changes (cells with perinuclear halo and atypical nuclei, sometimes with binucleation) (Figure 1E). Rare mitotic figures were detected and no signs of clear malignancy were evident.

Molecular tests did not confirm the presence of HPV infection and detected B‐RAFV600E mutation.

In both specimens, immunohistochemical analysis showed intense nuclear and cytoplasmic reactivity to p16 (Figure 1F) in >75% of neoplastic cells, nuclear positivity to p53 (Figure 1G) in 50% of neoplastic cells and reactivity to Beta‐catenin that was located at the tumor cell membranes (Figure 1H). Ki67 cellular proliferation index was low and most of the signal was located in the basal cells layer (Figure 1I) in both samples. What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis

Papillary craniopharyngioma with dysplastic changes.

Discussion

Craniopharyngioma is a benign epithelial tumor that represents 1.2%–4.6% of all intracranial tumors and with two clinicopathologic subtypes, the adamantinomatous and the papillary. The former is more common, affects with bimodal age distribution, is more prone to recurrence and is characterized by CTNNB1 mutation in 95% of cases. The papillary variant is less common, usually occurs in adults, often arise in supratentorial and third ventricular regions and shows BRAF V600E mutations in 81%–95% 1. Rarely craniopharyngiomas may show malignant transformation and it usually involves adamantinomatous forms 2.

Morphologic criteria of malignancy are not clear. According to the previous literature, at least three of the following features should be present: cellularity and increased nuclear‐cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromatic nuclei, increased mitotic activity or higher Ki67 expression, coagulative necrosis and other histologic features such as solid growth pattern, destruction of basement membrane, infiltrative growth and microvascular proliferation 3.

For years it was believed that malignant transformation was due to radiation exposure; however, it was shown that there is a poor correlation between the two 4, and some cases of malignant craniopharyngioma de novo or not associated with previous radiotherapy were described. Minimally invasive surgery aiming to achieve a “maximum allowed” removal combined with adjuvant radiotherapy is nowadays the most widely used option for the treatment of craniopharyngioma. In the present case, after the failure of endoscopic endonasal surgery, the occurrence of hydrocephalus hindered the second procedure scheduled for removal and the eventual radiotherapy.

The present case is peculiar because of atypical morphology shown especially by the second specimen. This severe cytological atypia has never been described in a case of papillary craniopharyngioma. No other criteria of malignancy were satisfied beyond pleomorphism, so we could consider this aspect as a form of dysplastic changes that could be explanatory of its biological aggressiveness (30% volume increase in 6 months).

References

- 1. Buslei R, Rushing EJ, Giangaspero F, Paulus W, Burger PC, Santagata S (2016) Craniopharyngioma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 4th edn. David NL, Hiroko O, Otmar DW, Webster KC (eds), pp. 324–328. Lyon: WHO/IARC. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lauriola L, Doglietto F, Novello M, Signorelli F, Montano N, Pallini R, Maira G (2011) De novo malignant craniopharyngioma: case report and literature review. J Neurooncol 103:381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sofela AA, Hettige S, Curran O, Bassi S (2014) Malignant transformation in craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery 75:306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang W, Chen XD, Bai HM, Liao QL, Dai XJ, Peng DY, Cao HX (2015) Malignant transformation of craniopharyngioma with detailed follow‐up. Neuropathology 35:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]