Abstract

The innate immune system in the central nervous system (CNS) is mainly represented by specialized tissue‐resident macrophages, called microglia. In the past years, various species‐, host‐ and tissue‐specific as well as environmental factors were recognized that essentially affect microglial properties and functions in the healthy and diseased brain. Host microbiota are mostly residing in the gut and contribute to microglial activation states, for example, via short‐chain fatty acids (SCFAs) or aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands. Thereby, the gut microorganisms are deemed to influence numerous CNS diseases mediated by microglia. In this review, we summarize recent findings of the interaction between the host microbiota and the CNS in health and disease, where we specifically highlight the resident gut microbiota as a crucial environmental factor for microglial function as what we coin “the microbiota‐microglia axis.”

Keywords: bacteria, CNS diseases, fecal microbiota transplantation, germ-free, gut-brain axis, microbiota, microbiota-microglia axis, microglia, short-chain fatty acids

The microbiota‐derived modulation of microglial function has been elucidated in several CNS disorders. Yet, the intricate link between the microbiota and microglia and its implications in the disease context necessitates further studies.

Introduction

The microbiota underwent millions years of symbiotic evolution in their hosts, however, the commensal microorganisms remained unnoticed until the beginning of the last century (1). The term “microbiota” collectively refers to the trillions of microbes, including bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea dwelling on surfaces and in different orifices of our bodies. Metchnikoff and Mitchell were struck by the large numbers of centenarians in a population in Eastern Europe and theorized that their lifestyle supported a healthy microbiota, which in turn affected their body functions and lead to a longer lifespan (1). Several factors as host lifestyle, geographical location, infections, diet, sex, age, and genetic background influence the diversity of the microbiota (2, 3). Thus, the microbiota is a system that integrates not only intrinsic signals, but also extrinsic environmental cues. The gut microbiota was shown to play indispensable roles in maintaining the intestinal barrier integrity in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), synthesis of vital vitamins as group B vitamins and vitamin K, metabolism of bile acids, sterols and xenobiotics, and hindering of pathogen adhesion to intestinal surfaces (4). It was found that the gut microbiota is crucial for the maturation and functional regulation of the peripheral immune system (5). These functions have rendered disturbances in the composition of the gut microbiota (known as dysbiosis) to be implicated in several diseases such as asthma (6), skin immunity (7) cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and autoimmune liver disease (8). Additionally, the gut microbiota has been implicated in multiple biological functions in the central nervous system (CNS). Under homeostasis, the gut‐brain axis influences the brain’s biology as neurophysiology, cognition, and behavior (9, 10). The gut microbiota has also been shown to regulate the permeability of the blood‐brain barrier (BBB) (11, 12), and glial cells functions (9). As such, several CNS diseases have been linked to dysfunctions of the gut microbiota (13, 14).

Microglia—the CNS resident macrophages—constitute a prime partnership with the gut microbiota due to their immune nature, sensitivity to microbial metabolites and proteins, and their constant surveillance of the CNS tissue (15). In contrast to other CNS cells that arise from the neuroectoderm, microglia’s ontogeny was traced to erythromyeloid precursors in the yolk sac (16, 17, 18, 19). Microglia are highly plastic and display heterogeneous transcriptional profiles according to the milieus of their microenvironment in the embryonic, early postnatal, and adult CNS (20, 21, 22). In the developing CNS, microglia support the maturation and survival of neuronal progenitors and their proper network integration through the secretion of neurotrophic factors like insulin‐like growth factor (IGF1) and brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (23). Furthermore, microglia largely contribute to the engulfment of cellular debris, synaptic refinement, and angiogenesis (23). In the homeostatic adult brain, microglia continuously survey their microenvironment (24, 25) and interact with neighboring CNS cells (26). In the diseased brain, microglia try to cope with pathological stimuli and are distracted to fulfill these myriads of physiological tasks. Thus, microglial dysfunction has been well characterized in multiple CNS diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson's disease (PD), and neuropsychiatric disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), depression, and schizophrenia (27). Again, in some of these disorders, microglia present distinct activation states to specific insults in the microenvironment, for example, in gliomas (28), through the activation of Amyloid beta (Aβ) in mouse models for AD or during demyelination (20, 29, 30, 31). Taking into account the crucial role of microglia for CNS immune responses and them potentially being active responder to peripheral stimuli, the former notion that the brain is “immune‐privileged” is losing traction (32). As a result, our understanding of the complex interactions between the gut‐microbiota derived signals and microglia, as well as intercellular influences, for example, as it was shown for microglia and astrocytes (33), has only started to unravel in the last 5 years.

In this review, we summarize the recent findings and provide perspectives that link the compositional states of the gut microbiota and microbiota‐derived signals to the microglial phenotype under homeostasis and in CNS disorders.

Gut microbiota modulates prenatal and adult microglia

With a critical gap in the knowledge of how environmental factors can affect microglia maturation and function, the microbiota has emerged as a hub for decoding the influence of several intrinsic and extrinsic factors and dissecting their contribution to the microglial phenotype in health and disease. Transcriptomic profiling by RNA‐sequencing (RNA‐seq) of microglia, isolated from germ‐free (GF) mice at different developmental stages (prenatal, postnatal, and adult), have revealed alterations in genes modulating immune cell functions (21, 34, 35). Indeed, experiments in adult mice have demonstrated the association between the microbiota and the control of microglia maturation and function (34). In the study, microglia of GF mice illicit a defective phenotype, where surface proteins, like colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1‐R), F4/80, and CD31 are upregulated compared to microglia from specific‐pathogen free (SPF) controls. Microglia in GF mice display higher cell density, consistent with the upregulation of genes promoting cell survival and proliferation as Csf1r, DNA‐damage‐inducible transcript 4 (Ddit4), and Transforming growth factor beta (Tgf‐ß) 1. In contrast to the SPF brains, microglia in GF brains have altered morphology, including more segments, longer processes and greater branching, and seem to lack the control on their homeostatic territorial distribution. Upon activation with immunostimulants such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), microglia of GF mice failed to induce an appropriate immune response. In recolonization experiments or the supplementation of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bacterial products produced through the catabolism of complex carbohydrates, can largely reverse the defective microglial features in mice lacking gut microbes. SCFAs, mainly comprised of acetate, propionate, and butyrate, function through either G‐protein‐coupled receptors (GPCRs) or histone deacetylases (HDACs) (36, 37). Taking into consideration, the HDAC inhibition activity of SCFAs, several studies have reported an enhancement of memory functions through the increased long‐term potentiation through HDAC inhibition by butyrate (38, 39, 40). However, mice deficient in SCFAs receptor Free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2)––normally not expressed in the brain––show comparable hyper‐ramified morphological phenotype while microglia density remains unaffected, suggesting a partial signal relay mediated by peripheral FFAR2‐expressing cells (34). In addition, the defective microglia phenotype is also observed in mice with altered microbiota such as the altered Schaedler flora (ASF) mice, which harbor a defined reduced set of bacterial strains (41), and mice treated with broad spectrum antibiotics (ABX) for acute depletion of microbiota. These findings highlight that a constant input from a complex microbiota is required to maintain microglia homoeostatic phenotype and function in adulthood. Nevertheless, ABX treated mice display normal microglia density and an unaffected expression of Ddit4. This discrepancy between the constitutive and acute depletion of the microbiota is suggestive of events preceding prenatal microglia maturation, which consequently leads to the defective microglia phenotype observed in adult mice.

Sex‐specific regulation of the gut‐brain axis has been identified as an important player in the impact of the microbiota on prenatal microglia. A study by Thion et al investigated the transcriptional and epigenetic profiles of microglia in GF mice at different developmental stages and in adulthood in both sexes. Microglia are known to have sexually dimorphic properties during development and in adult mice (35). Studies in adult mice have shown that male and female microglia differ in the rate at which they colonize the CNS and in the complexity of the immune response (42, 43, 44, 45). In line with these studies, Thion et al observed sex‐specific alterations in microglial morphology, transcriptomic, and epigenetic profiles at E18.5 and in adult mice. Genes associated with the apoptotic process, response to lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and inflammatory response were upregulated in microglia of female mice, suggesting that microglia are in a more immune‐activated state in females. At E14.5, close to the induction of sexual differentiation (46), only 19 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were regulated in microglia of embryos from GF mice compared to the SPF controls. The microbiota dependent effects became more pronounced at a later time point (E18.5), where microglia from both sexes showed downregulation of microglial differentiation and inflammatory responses‐associated genes (e.g., Aoah, Ly86, and Cd28). Moreover, upon epigenetic profiling of microglia by Assay for Transposase‐Accessible Chromatin sequencing (ATAC‐seq), Thion et al observed that GF‐conditions mostly led to reduced chromatin accessibility, reflected in the number of differentially accessible regions (DARs). However, these observations do not account for the transcriptomic differences, where the overall accessibility of the DEGs identified by transcriptomics is mostly unaffected. Furthermore, they attempted to clarify that several transcription factors (e.g., Irf8, Stat1, Klf2/4/6, and Jun/Fos) lying in the DARs have their putative target genes among the previously identified DEGs. Despite the differences in microglia densities observed between GF and SPF brains at the different stages, the microbiota effect was similar in both sexes. However, at transcriptomic level and under GF conditions, microglia from male mice display stronger effects in utero with a higher number of DEG at E18.5 compared to SPF control conditions. On the contrary, this sexual dimorphism is reversed at adulthood, with microglia displaying stronger microbiota‐dependent perturbations in in female GF mice. Acute microbiota perturbation with antibiotic administration produces a reverse effect between the sexes in the microglia of adult mice, with more DEG observed between ABX treated and SPF control in males than in females.

These recent findings emphasize the gut microbiota modulatory functions on the maturation and immune responses of microglia in the CNS under homeostasis.

The microbiota–microglia axis in CNS disorders

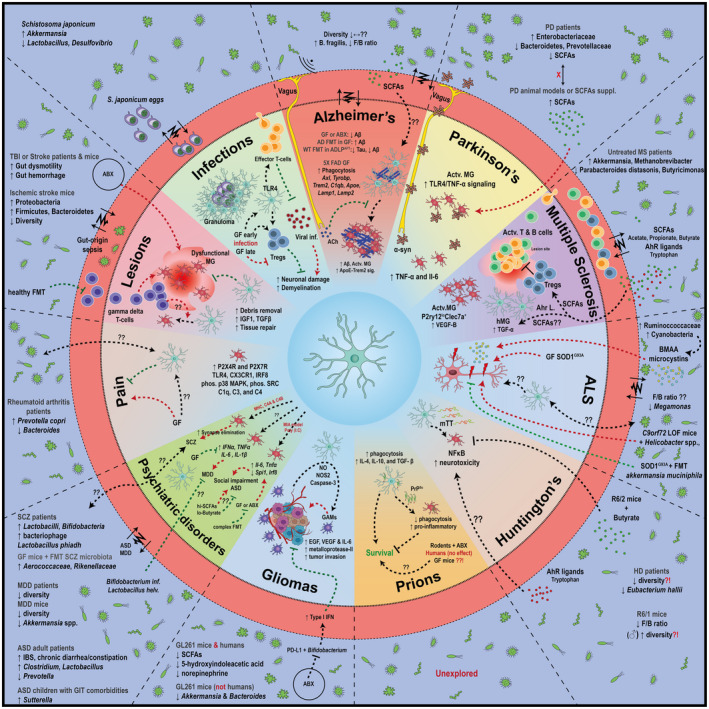

Microglia have been extensively investigated in the context of CNS diseases. Given their vital role to CNS physiology which is consistently impaired under pathological conditions due to tissue damage, cytokines or accumulation of toxic molecules, it is logical that microglia’s activated states are involved in the initiation or progression of several CNS neurodevelopmental, neurodegenerative, and neuroinflammatory diseases such as AD, PD, MS, and ASD (15, 27). Moreover, Hippocrates’s 2000 years old suggestion that all disease begins in the gut seems rather relevant, with alterations in the microbiota shown to correlate to several CNS diseases (10). As such, the gut microbiota is known to modulate neuronal activity through the active production of neurotransmitters (47), or via the action of gut‐derived metabolites such as SCFAs, where butyrate was reported to have a neuroprotective role in cisplatin‐induced hearing loss and models of PD (48). Given that the gut microbiota has emerged as key regulator of microglial function (13, 34), and microglia being involved in virtually all CNS pathologies, the microbiota–microglia axis became a critical link to CNS disorders (Figure 1), where additional research is essential to better understand the pathogenesis and identify new appropriate therapeutic approaches.

Figure 1.

The microbiota–microglia axis in the context of various CNS disorders. The impact of microbiota on certain neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, glioma, pain, etc. is highlighted. The known connections between the gut bacteria and disease pathology are indicated if available.

Alzheimer’s disease

Aging is a profound risk factor for AD, the most common neurodegenerative disease and cause of dementia, which is marked by a progressive cognitive decline. Despite the extensive research on AD in the last decades, we are still scratching the surface in understanding its complex pathology. AD is characterized by the accumulation of phosphorylated tau proteins and amyloid plaques consisting of amyloid β (Aβ), an enzymatic cleavage product of amyloid precursor protein (APP) (49, 50). The deposition of Aβ, which precedes the appearance of clinical symptoms, triggers an immune activation and leads to synapse loss and neuronal death. Microglia’s ability to phagocytose Aβ aggregates contributes to the progression of AD, where polymorphisms in phagocytosis, lysosomal degradation, and inflammasome activation modulating genes like TREM2, CD33, ABCA7, GRN , PYCD1, and APOE have been identified by genome‐wide association (GWA) studies in AD patients (15) or by overexpression in AD mouse models (51). It is hypothesized that Aβ arises as an antimicrobial response, where its physiological role in the CNS can be connected to an innate immune response to protect against brain infection (52). Notably, E. coli endotoxin potentiates the aggregation of Aβ in vitro (53). As a result of aging, the gastrointestinal epithelium exhibits a higher permeability to small molecules that is bi‐directional. Accordingly, it is debatable whether the penetration of gut‐derived bacterial molecules is alleviated via disturbed gut‐blood barriers and thereby causing increased levels of Aβ accumulation in the CNS. The alterations in tight junctions between the gut epithelium are attributed to dysbiosis of the gut microbiota when Bacteroidetes outnumbers Firmicutes and Bifidobacterium, whereas the increase in the intestinal permeability is relatively minor in the GF mice (54). Indeed, Bacteria from the genus Bacteroides (Pylum Bacteroidetes) shows an age‐dependent increase in the guts of wild‐type (WT) females, a phenotype even more pronounced in Tg2576 AD mice (Box 1), which was revered by caloric restriction regimen that reversed the APP‐associated gene expression in the intestine. Inoculation of B. fragilis DSM2151 in AD transgenic mice increased Aβ depositions and the progression of AD pathogenesis (55). In addition, there is a clear correlation in brain amyloidosis and pro‐inflammatory gut bacteria in cognitively impaired AD patients (Cattaneo et al, 2017). Compared to healthy controls, fecal microbiota from AD patients illicit diminished microbial diversity (Vogt et al, 2017). Taking into account the high individual variability between the microbiotas of human subjects, the situation in AD mouse models is as complex. Fecal microbiota from transgenic APP/PS1 mice have a reduced diversity than that of the WT littermates (Box 1). Indeed, APP/PS1 housed under GF conditions show less Aβ depositions (56). This phenotype is reversed in GF transgenic mice which received an FMT from WT or transgenic conventionally raised mice (56). However, two recent studies on 5xFAD transgenic mice (Box 1) observed no robust changes in the cecal and fecal‐microbiota diversity (57, 58). In contrast, another study applied repeated FMTs from WT mice to ADLPAPT mice (Box 1). Transgenic mice that receive the FMTs display less aggregation of Aβ plaques in their frontal cortices and hippocampi. In addition, less total tau and fewer activated microglia and astrocytes are detected in their hippocampi (59). These discrepancies in the reported differences in microbiota diversity between the different mouse models can be attributed to differences in the housing conditions, or alterations in the host genetics that could affect the microbiota composition (60). However, studies on APP/PS1 and 5xFAD transgenic models have agreeingly observed decreased Aβ depositions in transgenic mice housed under GF conditions and upon the acute depletion of the microbiota through ABX treatment (Figure 1) (56, 58, 61, 62, 63).

Box 1. Transgenic mouse models.

APP/PS1: An AD mouse model where CNS neurons express chimeric mouse/human amyloid precursor protein (Mo/HuAPP695swe) and a mutant human presenilin 1 (PS1‐dE9) (233).

5xFAD: An AD mouse model where CNS neurons overexpress mutant human amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein 695 (APP) with four Familial Alzheimer's Disease (FAD) mutations along with human presenilin 1 (PS1) (234).

ADLPAPT: An AD mouse model that accumulates both plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and loses hippocampal neurons created by crossing the 5XFAD strain with JNPL3 tau animals (59).

SOD1G93A: An ALS mouse model that expresses multiple copies of human SOD1 bearing the missense mutation G93A randomly integrated into chromosome 12 of the mouse (235).

C9ORF72: An ALS mouse model. The hexanucleotide‐repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the most common genetic variant leading to a loss of function (LOF) in C9ORF72, which heavily contributes to and exacerbates the pathogenesis of ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (236).

R6/1 & R6/2: HD mouse models that, driven by the human huntingtin promoter, express exon 1 of the human HD gene with around 115 and 150 CAG repeats, respectively (237).

Until recently, the precise cellular mechanism for the observed reduced Aβ accumulation was unclear. Hippocampi of GF housed 5xFAD mice display a lower burden of Aβ depositions as well as lower neuronal loss, a better performance in short‐term and working memory tests, and a remarkable difference in the microglia phenotype (58). Transcriptomic analysis of microglia isolated from the hippocampi of 5xFAD GF‐housed mice revealed a higher expression of phagocytosis‐related genes compared to SPF housed transgenic mice, including Axl, Tyrobp, Trem2, C1qb, Apoe, Lamp1, and Lamp2. In accordance, in vivo phagocytosis experiments using methoxy‐X‐O4, an Aβ labeling dye, showed an increase in the phagocytic activity of microglia in GF‐housed mice as compared to colonized 5xFAD mice at early stages of disease progression. Given that the production and processing of APP is not affected in the transgenic mice lacking microbiota, these data suggest that the gut‐derived amelioration of AD pathology in the GF mice results from the regulation of microglia Aβ clearance by the gut microbiota. Despite the similar decrease in Aβ depositions in the ABX‐treated transgenic mice, isolated microglia show a rather similar phenotype to the SPF‐housed mice, suggesting different mechanisms for the modulation of AD pathology (58).

As previously discussed, the microbiota can affect microglia in a direct or indirect manner through the production of metabolites which can reach the CNS. For example; short noninvasive stimulations of the vagus nerve in 12 months old APP/PS1 mice alleviates the activated morphology of the microglia through activation of the cholinergic anti‐inflammatory pathway (64). Furthermore, the role of SCFAs on the microbiota–microglia axis in AD has recently gained traction. Colombo et al have shown in GF housed APP/PS1 transgenic mice that supplementation with SCFAs for 8 weeks increases cerebral Aβ loads (61). SCFAs supplementation results in the specific activation of microglia, and not astrocytes, and is associated with the upregulation of ApoE‐Trem2 signaling in the brain. These results suggest that SCFAs are able to mediate similar effects to FMTs onto Aβ pathology, which are probably mediated by microglial activation. Additional studies are now required to identify coherent microbiota changes in AD, further dissect the specifics of how these alterations affect the microglia’s contribution to the disease progression, and highlight the missing links between the GF and ABX models.

Parkinson’s disease

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, with an underlying complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors, and is marked by the accompanying motor symptoms including rigidity, bradykinesia and resting tremors, and non‐motor symptoms, including chronic constipation and GI distress, that precede motor symptoms in up to 80% of PD patients (65). The disease progression of PD is majorly characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the accumulation of misfolded α‐synuclein (α‐syn) that assemble into fibrillary inclusions (66, 67). The accumulation of α‐syn aggregates, deposited by neuron‐derived exosomes, is thought to trigger microglial activation, which in turn worsens PD pathology through accelerating lethality of the distressed motor neurons by Tyro3, Axl, and MerTK (TAM)‐dependent phagocytosis (68). In addition, the increased number of activated microglia secrete pro‐inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF‐α and IL‐6), and other neurotoxic compounds, which chronically perpetuates the death of the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra, thus, aggravating the pathogenesis of PD (68, 69).

Given the fact that non‐motor symptoms, such as colonic dysfunction, are prominent symptoms in the majority of patients, some studies hypothesized that the gut enteric system is a potential contributor to the neuropathogenesis. α‐syn aggregates are detected in the gut much earlier than in the brain, a retrograde transport of α‐syn to the brain can be speculated in cases of sporadic PD (70, 71). The alterations of the gut microbiota observed in PD patients mediate a local inflammation and eventually lead to an abnormal intestinal permeability, which may promote the systemic spread of α‐syn that can then reach the CNS (72). Another proposed high‐way for α‐syn to the CNS is the vagus nerve, where full truncal vagotomy in PD patients dampens the disease progression (73). On the contrary, vagus nerve stimulation combined with LPS challenge in mice has reportedly decreased the pro‐inflammatory production of TNF‐α and IL‐6 by microglia, an effect no longer observed in vagotomized mice (74). While further investigation is needed, these data support the vagus nerve hypothesis as a route for the propagation of α‐syn with the eventual activation of microglia. Yet, several studies have supported the notion that the gut‐microbiota exacerbates the disease. Indeed, fecal microbiota of PD patients have a different composition compared to healthy subjects and the abundance of certain bacterial strains can be correlated with the severity of the motor deficits. PD patients present with elevated abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes and Prevotellaceae with a reduced production of SCFAs when compared to matched controls (75, 76, 77). Li and colleagues suggested that there is a continuous decrease in fiber‐degrading bacterial strains leading to a decrease in SCFAs production in PD patients (78). These findings were confirmed by studies in transgenic GF mice, overexpressing the human α‐syn, which display reduced gut dysfunctions, motor deficits, and microglial activation compared to conventionally housed mice (Figure 1) (79). Moreover, supplementation of these transgenic GF mice with SCFAs induced microglial activation and motor deficits similar to those observed in the control mice (79). Additionally, FMT from healthy mice to mice injected with 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1,2,3,6‐tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), a toxin‐induced model of PD, decreased SCFA levels, alleviated physical impairment and attenuated microglial activation, where Toll‐like receptor (TLR)4/TNF‐α signaling pathway components were downregulated (80). A recent study used the MPTP chronically in low doses to model PD in non‐human primates (rhesus monkeys) (81). Joers et al show that inhibition of TNF signaling by a sTNF‐specific biologic XPro1595 mitigates inflammatory responses and ameliorates non‐motor symptoms in MPTP treated monkeys. They further describe a sexually dimorphic response to the MPTP treatment in females rather than in males, reflecting the earlier onset of PD in humans (82). They demonstrate specific alterations in gut microbiota and an increase in SCFAs abundance upon MPTP treatment, which are associated with a PD‐like phenotype in the substantia nigra confirmed by Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and accompanied microglial activation (81). Collectively, these findings highlight the involvement of gut dysbiosis in PD, and suggest that SCFAs are sufficient to promote the α‐syn‐mediated exacerbation of PD symptoms (Figure 1). Despite the compelling evidence associating gut dysbiosis and microglia in PD, the results remain but correlative and further characterization of the microbiota–microglia link in PD is required.

Multiple sclerosis

MS is a chronic neurodegenerative T‐cell‐mediated autoimmune disease of the CNS that primarily deteriorates the myelin sheath that physiologically enwrap neuronal axons. Peripheral and CNS‐resident immune cells are involved in the pathogenesis of MS, where an imbalance between the pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cellular populations occurs at the lesion sites (83). Microglia play an immunomodulatory role at the lesion site and were reported to interact with the invading T‐cells (84). In addition, GWA studies have found several microglial genes to be associated with MS, including TNFSF1A, IRF8, PLEK, and CLEC1 (85, 86). Recent findings have pointed at the potential contribution of the gut microbiota to MS. (Figure 1). Untreated MS patients show increased abundance of bacterial genus like Akkermansia and Methanobrevibacter, whereas genus such as Parabacteroides distasonis and Butyricimonas have a reduced abundance (87, 88, 89). In a spontaneous relapsing‐remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model of MS, GF mice display complete protection from disease initiation (87, 90). Similarly, the acute depletion of the microbiota in ABX‐treated mice attenuates EAE progression (91). These effects are accounted to the dampening of T‐ and B‐cell responses and the induction of regulatory T cell (Tregs) responses (92). ABX treatment in mice with lysolecithin‐induced demyelination increases the number of activated P2ry12loClec7a+ microglia and impairs myelin regeneration. However, in a cuprizone‐induced demyelination model, GF mice display a reduced number of microglial cells and greater number of oligodendrocytes, an effect reversed by switching the GF mice to SPF conditions (93). The remyelination phenotype observed in the GF mice is not reproducible in the ABX‐treated mice (93). Interestingly, GF mice which receive FMTs from MS patients elicit worsened symptoms of EAE than in the mice that received FMT from healthy individuals (94). In a transgenic mouse model of MS, FMT of MS twin‐derived microbiota induced a higher autoimmune response than the healthy twin‐derived microbiota (87). Moreover, SCFAs, as regulators of Treg function (95), can modulate the pathogenesis of MS. SCFAs supplemented mice, specifically acetate, demonstrate reduced severity of EAE by HDAC inhibition (95). Similarly, studies with butyrate supplementation show a suppression in demyelination and an enhancement of remyelination by inducing oligodendrocyte maturation and differentiation (96). The role of SCFAs in MS was also confirmed in preclinical studies as well as in humans. MS patients that received long‐term propionate supplementation showed a reduced relapse rate and disease progression, mediated by an enhanced activity of Tregs (97, 98).

The microbiota–microglia axis was recently implicated in the microglia‐astrocyte crosstalk during EAE, through bacteria‐derived aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands (33). AhR ligands (e.g., derivatives of tryptophan) are produced by a few bacteria, such as peptostreptococcus russellii and Lactobacillus spp (99). AhR‐signaling on microglia, by microbiota‐derived metabolites of dietary tryptophan, leads to transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα) and vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGF‐B) production, which subsequently modulate the pathogenic activities of astrocytes in the EAE mouse model of MS and human MS patients. More specifically, TGFα acts via the epidermal growth factor receptor (Erbb)1 and dampens the pathogenic activities of astrocytes, while VEGF‐B activates FLT‐1 signaling in astrocytes, exacerbating the disease. In fact, AhR‐deficient microglia caused aggravated EAE without affecting the peripheral immune responses, indicating that AhR activation in microglia prevents inflammation specifically in the CNS. Taken together, these findings highlight microglia as a crucial link between the microbiota and MS disease initiation and progression (Figure 1).

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

ALS is a progressive and ultimately fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects motor neurons in both the brain and the spinal cord. It is the most severe and most common form of motor neuron degeneration in adults. ALS is mainly characterized by the generalized muscle weakness, but extra‐motor features also include cognitive and behavioral disturbances. ALS can be sporadic (SALS) or familial (FALS). Genetic susceptibility, including mutations in chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72), superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), fused in sarcoma (FUS), and transactive response DNA‐binding protein 43 (TARDBP; TDP‐43), and environmental factors are thought to play a role in the multi‐stage process of ALS pathogenesis (100). Studies on postmortem tissue from ALS patients and related ALS mouse models elicited increased levels of microglial activation and higher microglial densities in areas that display neuronal loss (101, 102). Moreover, microglia expressing mutant SOD1 G93A (Box 1) are more activated and neurotoxic than WT microglia due to the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (103), resulting in an accelerated disease progression (104).

In addition to the clear involvement of microglia, alterations of the gut microbiota is associated with ALS pathogenesis (Figure 1). In an initial study on a restricted number of ALS patients, Ruminococcus spp. showed a lower abundance, with a shift in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio toward higher abundance of Bacteroidetes compared to the healthy controls (105). Another study, encompassing more ALS patients, detected a higher OTU richness in ALS patients with respect to controls, without significant differences in biodiversity indices (106). In a more recent study, Zeng et al found a similar shift in the F/B ratio, in agreement with Rowin et al, and additionally detected a lower abundance of Megamonas in ALS patients compared to control individuals (107), confirming the involvement of the F/B ratio shift in the microbiota‐derived ALS phenotype. A more in‐depth metagenomics analysis coupled with metabolomics on the microbiota of ALS patients revealed discrepancies of the microbiota at the species level with altered metabolic products, which the authors claim to pave the road for the use as biomarkers in ALS (107). In contrast, Di Gioia et al, reported no difference in the F/B ratio in ALS patients (108). However, Di Gioia et al observed an increase in the abundance of Ruminococcaceae and Cyanobacteria, which produce several neurotoxic metabolites such as β‐methylamino‐l‐alanine (BMAA) and microcystins, and a lower diversity of the microbiota in ALS patients compared to controls, which further decreased as the disease progressed. Administering a probiotic formulation of a mixture of five lactic acid bacteria to ALS patients for 6 months, neither reverses the microbial diversity of the ALS patients, nor influences the progression of the disease (108). Therefore, the microbial profiling of ALS patients remains inconclusive and further investigations are required to elucidate the precise role of putative altered gut microbiota in ALS patients. Nevertheless, preclinical studies in SOD1 G93A transgenic mice (Box 1) revealed impaired intestinal permeability and alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that precede the development of motor neurons dysfunction, suggesting the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota as a potential factor in the onset of ALS (109). However, contrary to observations in other neurodegenerative diseases like AD and PD, GF, or ABX‐treated SOD1 G93A transgenic mice show an exacerbated pathogenesis of ALS. In the ABX‐treated SOD1 G93A transgenic mice, colonization with Akkermansia muciniphila show beneficial effects, whereas in accordance with the human data, colonization with Ruminococcus worsens the disease progression (109). Replenishment of probiotics and the relevant metabolites in SOD1 G93A transgenic mice ameliorates the motor deficits (110). A recent study utilizing the C9ORF72 ALS transgenic mouse model (Box 1) demonstrated interesting findings involving the microbiota–microglia axis in ALS (111). After different studies on C9orf72 LOF mutant mice, investigating the same allele on a similar genetic background, have reported inconsistent data on the long‐term survival between homozygous, heterozygous, and WT mice (112, 113, 114, 115), Burberry et al aseptically re‐derived C9orf72‐mutant mice from a facility in Harvard (C9orf72(Harvard)) into a new facility at the Broad Institute (C9orf72(Broad)). Yet again, both the mutant homozygous and heterozygous C9orf72(Harvard) mice were at an increased risk of premature mortality, while the C9orf72(Broad) mutant mice showed no differences to the corresponding WT controls (111). After controlling for environmental factors that might contribute to this phenotype, microbial screening reports from the two facilities revealed an increased abundance of murine norovirus, Helicobacter spp., Pasteurella pneumotropica, and Tritrichomonas muris in C9orf72(Harvard) mice than in C9orf72(Broad) mice. Indeed, chronic ABX treatment in the C9orf72(Harvard) mice cohort or FMTs from the pro‐survival C9orf72(Broad) into C9orf72(Harvard) mice cohorts prevented the peripheral inflammation and autoimmunity. Upon further profiling of the fecal microbiota of the FMT groups, Burberry et al identified Helicobacter spp. as the main mediator of the decreased survival in the C9orf72(Harvard) mice cohort. In addition, they report an increased myeloid cell infiltration, microgliosis, and upregulation of the pro‐inflammatory dectin 1, C‐C motif chemokine receptor (CCR)9, and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) on microglia in spinal cords of C9orf72(Harvard) mutant mice (111). These findings highlight the role of the microbiota–microglia axis in the onset and progression of neurological disease in ALS patients with C9ORF72 mutations (Figure 1).

In summary, ALS mouse models have altered microglial and microbiota profiles, and with further research, these phenotypes will need to be associated in the context of the pathology. In addition, the effects of the different colonization or probiotic interventions on microglial function in the context of ALS require more investigations. The microbiota–microglia axis implications in ALS are only starting to unravel.

Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease (HD), an autosomal dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disorder, is caused by expanded CAG repeats (>36) in the HTT gene, which leads to the production of misfolding‐prone mutated huntingtin (mHTT) protein. The characteristic symptoms of HD range from cognitive disorder, mental disturbance to typical motor impairments (116). Despite the ubiquitous expression of the mHTT in the CNS, loss of the striatum’s medium spiny neurons (MSNs), and atrophy in the caudate and putamen regions seem to be prominent (117). The neuronal expression of mHTT, which preferentially forms aggregates along neuronal processes and axonal terminals, initiates a local activation of microglia along the irregular neurites, leading to elevated microglia cell density and activated morphology (118). As a result of the interaction of mHTT with IκB kinase complex, the activated microglia are thought to be involved in the neurodegeneration in HD due to their release of downstream NF‐κB‐dependent neurotoxic pro‐inflammatory cytokines (119). mHTT‐expressing microglia isolated from R6/2 mice, a transgenic mouse model for HD (Box 1), elicit an elevated response to immune challenge compared to microglia of WT mice (120). These findings highlight the involvement of microglia in the pathogenesis of HD.

In addition, recent studies have investigated the status of the gut microbiota in HD. Wasser et al found the fecal microbiota of HD patients to have less diversity than that of the control individuals. In particular, low abundance of Eubacterium hallii in symptomatic patients is correlated to severe motor symptoms and memory decline. They also report stronger differences due to the HD pathology in male than in female participants. Despite the low sample number (42 patients), this is the first study linking HD pathogenesis to gut dysbiosis in humans (121). Furthermore, a study in R6/1 transgenic mouse model of HD (Box 1) observed that the HD gut microbiota shows an increase in Bacteroidetes and a proportional decrease in Firmicutes (122), a dysbiosis previously reported in aging and AD (54). In contrast to the report in HD patients, Kong et al observed higher microbiota diversity in HD mice, which coincides with impairment of body weight and motor deficits. Yet, male mice seem to be more affected, where female HD mice show no difference in microbiota diversity compared to the WT controls (122).

The involvement of the microbiota–microglia axis in HD is still vague (Figure 1). However, butyrate treatment of R6/2 HD mice increases their survival rate and delays the neuropathological symptoms, suggesting the possible link to SCFAs‐derived microglial effect (123). Additionally, given the growing evidence of the role of activated astrocytes and their interaction with the microglia in exacerbating the pathogenesis of HD (124), the previously discussed link between the microbiota‐derived Ahr ligands on microglial Ahrs and the downstream modulation of astrocytic activation could be of relevance to HD.

Prion diseases

Prion diseases, or transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, are a group of progressive and fatal neurodegenerative diseases that among others, include Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) and kuru in humans, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle. The hallmark of prion diseases manifests in the deposition of scrapie prion protein (PrPSc), a misfolded form of cellular prion protein (PrPC), in the CNS eventually leading to spongiform change, gliosis, and neuronal loss (125). In prion‐infected mice, microglia are observed surrounding PrPSc deposits, and intracellular PrPC is also detected in microglia, suggesting that they could disseminate prion within the brain. However, at early stages of prion infection before the onset of clinical symptoms, microglia acquire a phagocytic phenotype, which is facilitated by the astrocyte‐derived opsonin milk fat globule‐EGF factor 8 (MFGE8), in addition to their secretion of anti‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐4, IL‐10, and TGF‐β. This phagocytic anti‐inflammatory microglial phenotype is opposed by the sustained PrPSc accumulation and the eventual insufficient clearance by microglia switches them to a pro‐inflammatory phenotype, which eventually exacerbates neuronal death (125).

Studies investigating the potential contribution of the gut microbiota to the pathogenesis of prion diseases have been inconsistent. ABX treatment in rodents at the initial stages of prion disease increases their survival time (126). However, CJD patients, treated daily with doxycycline in the context of a clinical trial, showed no beneficial effect on the disease progression (127). Initial experiments on GF mice by Lev et al show that GF mice injected intracerebrally with the Chandler mouse‐adapted scrapie isolate (irradiated scrapie brain homogenate) present extended survival (128). A subsequent study by Wade at al. describes an extension in the survival of GF mice only upon intraperitoneal, but not intracerebral, injection of ME7 scrapie prions, when compared to mice with a defined microbiota comprising particular bacterial species of Clostridium, Bacillus, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides (129). However, a more recent study by Bradford et al shows that the exposure to prions by intraperitoneal or intracerebral injection did not affect the susceptibility or survival of the GF compared to SPF mice. In addition, they report neither a difference in disease development, nor in the distribution and the magnitude of activation of microglia in the GF mice based on histological analyses (130). Given these findings, the role of the gut microbiota in prion diseases remains controversial (Figure 1) and additional detailed investigations including gene expression analysis are required to characterize the microglial activation state and contribution to prion pathogenesis.

Due to the etiology of prion diseases, where 90% of the cases are sporadic, and their infectious potential, it is hypothesized that the gut, acting as an entry point for prion agents, can be a site for the initial accumulation and spread of PrPSc (131). However, the involvement of the microbiota–microglia axis in the pathogenesis of prion diseases is currently unclear.

Psychiatric disorders

Autism spectrum disorder

ASD is an array of neurodevelopmental disorders that is associated with a wide range of cognitive and behavioral symptoms (132). While the etiology of ASD is complex and incompletely understood, microglia are thought to be involved in the course of the disease, which ultimately manifests in the ASD behavioral phenotypes. The pathogenic dysfunction of microglia in ASD is associated with the stunted neuronal development via the dysregulated microglia‐mediated synaptic remodeling (133). Studies in ASD mouse models have highlighted the involvement of microglia in the disease pathogenesis. Mice lacking fractalkine receptor Cx3cr1, a crucial interlink for neuronal–microglial communication, elicit an impaired synaptic density, an immature brain circuitry, and social behavioral deficits, similar to those seen in ASD patients, that persist into adulthood (134, 135).

Interestingly, 23%–70% of ASD patients suffer from GIT comorbidities such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic diarrhea, and/or constipation (136). The prevalence of GIT comorbidities in ASD has prompted investigations to tease out the implications of the microbiota on the etiology of ASD. Indeed, the gut microbiota of ASD individuals shows alterations in diversity and composition compared to neurotypical controls. The abundance of Clostridium and Lactobacillus is elevated in ASD individuals, while beneficial bacterial populations like Prevotella are reduced (137). Intestinal biopsies from children with ASD, suffering from GIT disturbances, showed higher abundance of Sutterella than in control samples (138). Moreover, GF Swiss Webster and C57BL/6 mice display defects in sociability, which is reversed by colonizing the GF mice during the juvenile stage (139, 140). Similarly, ABX treatment during the perinatal stages negatively impacts social behavior (141, 142). In addition, using FMTs as a therapeutic approach for ASD alters in the gut composition, leading to an improvement in both GIT and behavioral symptoms of ASD (143). Mice that received an FMT from human ASD donors, elicited ASD‐related behavioral deficits (144). These findings suggest that the gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in social development and is relevant to the pathogenesis of ASD.

The role of the microbiota–microglia axis in driving the pathology of ASD has been highlighted in several models of ASD (Figure 1). The offspring of the maternal immune activation (MIA) model, a model developed to mimic the increased incidence rate of ASD in children whose mothers suffered from a severe infection during pregnancy, not only exhibit GIT dysfunctions like gut dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability and intestinal inflammation (136, 145), but the microglia of these mice also display an increased expression of pro‐inflammatory genes (e.g., Il‐6, and Tnfα) and downregulation of genes usually expressed during early development like Spi1 (encoding PU.1) and Irf8 (21, 146), suggesting that the maternal inflammation disrupts the gut ecosystem and the maturation of microglia. Given the role of SCFAs in modulating microglial maturation and function (34, 61, 79), it is reasonable to further investigate the regulation of SCFAs’ production in the dysbiosis state of the microbiota in ASD. Currently, Children with ASD are reported to have both lower (147) and higher (148) fecal SCFA levels than controls. Surprisingly, treatments with different types of SCFAs induce opposite effects in ASD models. Rodents, which are administered high doses of propionate, elicit ASD‐ike behavioral deficits such as repetitive actions and impaired social interaction, abnormal hippocampal histology, and activated microglia with transcriptomic alterations and production of neurotoxic cytokines (149). On the contrary, through the epigenetic effect of HDAC inhibition, butyrate treatment at lower doses has a beneficial effect on the social impairment of a strain‐based ASD‐like model, the BTBR mouse model (150). In summary, these findings suggest a potential correlation between the microbiota dysbiosis and microglial dysfunction in ASD, however, the clear involvement of the microbiota–microglia axis in ASD remains uncertain.

Major depression

Our understanding on the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder (MDD) is limited. MDD is characterized by anhedonia (reduced ability to experience pleasure from natural rewards), irritability, cognitive deficits and abnormalities in appetite and sleep (“neurovegetative symptoms”). MDD is often associated to other complications such as coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes (151). Subsets of MDD patients are reported to have volumetric decreases in several forebrain regions and in the hippocampus, which is supported by a notion that decrements in neurotrophic factors that regulate the brain’s plasticity such as BDNF, contribute to the pathogenesis of the MDD. Indeed, stress reduces BDNF‐mediated signaling in the hippocampus, while chronic treatment with antidepressants rescues the BDNF‐mediated signaling (152). Microglia are able to produce both pro and mature BDNF, which exerts its action on neurons promoting learning and synapse formation (153). In addition to the role of BDNF signaling, several studies have reported an association between MDD and a pro‐inflammatory signaling through cytokines such as interferon (IFN)‐α, TNF‐α , IL‐6, and IL‐1β (154). Depression is a common side effect in a subset of individuals treated with recombinant interferons (155). Mice deficient in IL‐6 and TNF‐α receptors, show antidepressant‐like behavioral phenotypes, and the blocking of IL‐1β receptor reverses the anti‐neurogenic and anhedonic effects of chronic stress (151). The BDNF and cytokine hypotheses, support the claim that MDD is a microglial disorder. Postmortem brains of MDD patients, who committed suicide, exhibit increased microglia cell numbers and varying degrees of microglial activation (156, 157). Moreover, animal models of MDD confirm the findings of activated microglia (158).

Analysis of fecal samples from MDD patients demonstrate robust differences in the beta diversity of the gut microbiota between depressed and control individuals (159, 160). In humans, ABX treatment in the first year of life is correlated with depression later in life (161). Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of MDD patients is accompanied with increased gut permeability, which correlates with MDD severity in adolescents (162). GF mice, which receive FMT from depressed patients or depressed mice, exhibit depressive‐like behaviors compared with colonization with microbiota derived from healthy controls (163). Likewise, FMT experiments show a similar phenotype in rats (164). A study on socially defeated animals, reported that increased stress reduces the overall diversity of the gut microbiota, and relative abundances of numerous bacterial genera, including Akkermansia spp., which positively correlates with behavioral metrics of both anxiety and depression (165). Probiotic supplementation with Bifidobacterium infantis or Lactobacillus helveticus Ns8, improves the behavioral and biochemical deficits in chronically stressed animals (166, 167). In accordance with previous studies on the response of microglia in GF mice to immune stimulation by LPS (34), it was shown that GF mice are more resistant to LPS‐induced anhedonia‐like behavior, possibly due to the lower production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, namely TNF‐α (168).

The link between the microbiota and microglia in MDD (Figure 1) remains unclear and further studies are required to address the potential synergistic mechanisms, which can be targeted to alleviate the burden of MDD.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a debilitating disorder with unknown pathogenic mechanisms. SCZ involves emotional, and cognitive impairments, and is characterized by positive (e.g., delusions, hallucinations), and negative symptoms (apathy, withdrawal, and slowness). SCZ patients exhibit gray matter loss, reduced hippocampal size, cortical thinning and functional hypoactivity, which arise due to the impaired hippocampal neurogenesis, and low spine density in the cortex and hippocampus (169, 170). Analysis of genome variations in SCZ patients, identified variations in the MHC locus, involving distinct complement component 4 (C4) alleles that affect expression of C4A and C4B in the brain, and are known to promote synapse elimination during the maturation of the neuronal circuit (171). In addition, C4 complete knockout mice display impaired synaptic refinement (171) and its deficiency increased phagocytosis of synaptosomes by human iPSC‐derived microglia in vitro (172). C4 is expressed by neurons, localized in dendrites, axons, and synapses, and upon secretion is intercepted by the complement‐cascade in microglia, whose excessive or inappropriate synaptic pruning during adolescence and early adulthood could exacerbate the pathogenesis of SCZ (171).

Although, based on studies in monozygotic twins, the heritability of SCZ is estimated at ~80% (173), the risk profiles from the SCZ associated alleles only explains ~7% of variation in the liability to the disease (174), hinting toward the impact of the environmental factors, that is, the gut microbiota, to the pathogenesis of SCZ. One hypothesis postulates that gut dysbiosis, changes in microbial diversity and deficits in the intestinal barrier in ASD patients (175), could allow the passage of antigenic GIT products which can further activate the complement system in immune cells like microglia (176, 177). Analysis of the oropharyngeal microbiome of SCZ patients revealed an increased relative abundance of the immunomodulatory bacterial genera Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria compared to healthy controls (178). Moreover, another study showed altered levels of the bacteriophage, Lactobacillus phiadh, which infects bacteria from the genus lactobacilli (179). Similar tendency in the abundance of Lactobacilli were observed in fecal microbiota of SCZ, with a positive correlation between their abundance, the disease severity and the resistance to therapy (180). However, a more recent study by Zheng et al observed difference in the gut microbiota of SCZ patients, but reported no comment on the status of Lactobacilli abundance (175). However, in FMT experiments, where GF mice received FMT from SCZ patients, the recipient mice develop SCZ‐relevant behaviors such as locomotor hyperactivity, decreased anxiety‐ and depressive‐like behaviors, and increased startle responses. Zheng et al attributed this SCZ phenotype to the FMT and more specifically to the bacterial families Aerococcaceae and Rikenellaceae, which can modulate the glutamate‐glutamine‐GABA cycle (175).

To date, the microbiota has yet to be directly linked to microglia in SCZ (Figure 1). However, the importance of microglial complement‐mediated phagocytosis and synaptic pruning to the progression of the disease could inspire microglial profiling in GF SCZ‐mouse models similar to what Mezö et al observed in AD with the modulatory action of the microbiota on microglial Aβ uptake (58). In addition, it would be interesting to address the hypothesis whether the probiotic supplementation of Lactobacilli directly or indirectly influences the microglia in the context of SCZ.

Gliomas

Gliomas are the most common primary lethal tumors of the CNS, which are thought to arise from neuroectodermal stem cells, with 50% of patients presenting with the most aggressive form of the disease, and dismal mortality rates: glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) (WHO‐grade IV) (181). Patients diagnosed with GBM have a 5‐year survival rate of only 3.3% and a median survival time of 14.6 months (182). Gliomas, similar to other solid cancers, acquire a complex microenvironment that influences tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Up to 30% of the glioma’s tumor mass is comprised of myeloid cells, predominantly microglia (183). Microglia have a role in gliomal pathogenesis by promoting gliomal migration and proliferation (184). In addition, glioma‐associated microglia (GAMs) acquire a distinct glioma‐induced activation status that differs from typical inflammatory phenotypes (28). GAMs upregulate EGF, VEGF, and IL‐6, which promote tumor proliferation, and metalloprotease‐II, which enhances tumor invasion (184). while microglia might show reduced phagocytosis of glioma cell, they show increased phagocytosis of bacterial debris or other nonmalignant cells (185). This has created controversy as to the phagocytic activity of GAMs. It was recently shown that the polarization of microglia toward a glioma‐supportive phenotype is mediated through gliomal NOS2‐derived NO, which transforms GAMs through a caspase‐3‐dependent pathway (186). Collectively, the intricate interaction of microglia with glioma cells, suppresses the microglial immune surveillance capacity, further promoting the pathogenesis of glioma.

Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated the potential role of the microbiota in modulating the immune system in the tumor environment, and shown the possibility of utilizing the microbiota for biomarker, and therapeutic approaches in several tumor types (187, 188). In combination with PD‐L1 blockade, the oral administration of Bifidobacterium in mice abolishes tumor growth by activating immune cell components and type I interferon signaling (189). The gut microbiota is known to enhance the effects of total body irradiation and adoptive T‐cell therapy, therapeutic approaches, which are beneficial for tumor regression via a metabolite of LPS (190). However, the role of the microbiota in glioma has only recently started to unravel. In a GL261 murine glioma model and a small glioma patients cohort (six patients), one study has shown an increase in the relative abundance of Akkermansia and Bacteroides levels after tumor growth in mice but not in human (191). However, the levels of fecal metabolites such as SCFAs, namely acetate, propionate and butyrate, 5‐hydroxyindoleacetic acid, and norepinephrine are reduced following tumor growth, with no effect of the applied chemotherapy (191). In accordance with the findings from Sivan et al, another recent study on the GL261 mice demonstrated that ABX treatment exacerbates the glioma growth (192). Aside to the alteration in natural killer (NK) cell numbers and activity, the authors showed that ABX treatment increases the expression of Arg1, P2ry12, and Inos in the brain, without changing microglia cell density, and confirms the increase in ARG1 and P2RY12 proteins in microglia (192). Taken together, these findings support the notion of a functional gut microbiota–microglia axis whose modulation can be beneficial for tumor suppression in glioma (Figure 1).

Pain

Pain, a multimodal experience which involves complex mechanisms including molecular and cellular transduction pathways and neuronal plasticity, is usually transient (acute pain) or sustained and nonreversible (chronic pain) (193). Microglia were shown to be critically involved in the development and persistence of the adaptations that derive the transition from acute to chronic pain (194). Peripheral nerve injury, alterations in the local neuronal activity, and the release of neuronal cytokines such as Cxcl1 in the spinal cord activate spinal cord microglia (195). After nerve injury, the microgliosis mainly mediated by the proliferation of the resident spinal cord microglia (196) is accompanied by a complex myriad of immune responses. Several microglial receptors and transcription factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic pain including purinergic receptors P2X4R and P2X7R, TLR4, CX3CR1, phosphorylated p38 MAPK, phosphorylated SRC, IRF8, and complement components C1q, C3, and C4 (194).

In addition, the link between chronic pain and the gut microbiota has been gaining traction. In models of visceral pain, GF exhibit an increased sensitivity to pain (197). Furthermore, GF rats, which received an FMT from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients characterized by hypersensitivity to colorectal distension, showed an enhanced visceral pain response (198). Studies on rheumatoid arthritis have described an altered microbiota, particularly increased abundance of Prevotella copri and a decrease in Bacteroides, in untreated new‐onset rheumatoid arthritis patients compared to healthy controls (199). Moreover, studies in human patients demonstrated gut microbiota alterations in other pain disorders, including chronic pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, with changes in microbiome diversity, and abundance compared to healthy controls (200). Despite the existing evidence that highlight the roles of the microbiota and microglia in pain and the potential for targeting either as therapeutic approaches (200), the link between both in regulating the underlying mechanisms that orchestrate pain remains unclear (Figure 1).

Brain lesions (trauma and stroke)

Brain lesions induced by traumatic brain injury (TBI) or ischemic stroke are major causes of disability worldwide. The progressive neurodegeneration that follows the acute lesion, caused by TBI or stroke, is a major risk factor for chronic neurological complications such as dementia (201, 202). TBI and stroke initiate a cascade of events that start with the local death of damaged neurons and the rapid inflammatory response mediated by the infiltrating blood‐borne immune cells and the resident microglia (203). During the early phases of the disease, the resident microglia are crucial for debris phagocytosis and providing trophic support, by secreting anti‐inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, such as Insulin Like Growth Factor (IGF) 1 and TGF‐β, to promote tissue repair (204). Enhancing the microglia population by transplantation to the lesion site can ameliorate the ischemia‐derived damage (205). However, over time as the lesion extends from core to penumbra, the excessive amount of debris overloads the microglia and renders them dysfunctional (206).

The notion of a bi‐directional link between brain injury and the gut microbiota has been supported by several studies. After TBI or stroke, a large subset of patients suffers from GIT complications, including gut dysmotility, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and impaired intestinal barrier, which can eventually lead to gut hemorrhage, and even gut‐origin sepsis (207, 208). Similarly, brain and spinal cord injury (SCI) animal models exhibit altered gut composition, and disrupted motility and permeability of the intestinal wall (209). Conversely, depletion of the gut microbiota by ABX treatment, worsens the outcome of stroke (210), and exacerbates both neurological impairment and spinal cord pathology post‐SCI (211). In mouse models of ischemic stroke, diversity of the gut microbiota is reduced in mice with a severe stroke, whereas the microbiota of mice subjected to a mild stroke is identical to controls. FMTs from healthy mice reduce brain lesion size and improve health (212). In a gnotobiotic mouse model of ischemic stroke, the increase in the relative abundance of Proteobacteria is accompanied by a reduction in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes altered immune system homeostasis. The immune signaling cascade eventually decreases the pro‐inflammatory gamma delta T cells and IL‐17, which plays a role in chemokine production in the brain parenchyma and infiltration of cytotoxic immune cells, resulting in a reduction in ischemic brain injury (213). Given the regulatory effect of the microbiota on microglial function, including phagocytosis, during homeostasis and disease (13), the perturbations in the gut microbiota post‐TBI or stroke can be relevant to the disease prognosis. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that SCFAs supplementation has a beneficial role on poststroke neuronal plasticity, through the modulation of T cells recruitment into the brain, which in turn regulates microglial function in synaptic remodeling (Figure 1) (214). More studies are required to confirm the link between the microbiota to the trophic role of microglia in brain lesions.

Microbial and parasitic infections

Despite the complex immune system and the intricate BBB, large number of viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites are “neurotropic,” that is, with a predilection for infecting the nervous system, and manage to evade these defenses (215). The involvement of microglia as the CNS guardians is not limited to their direct action on the invading pathogen, as it also includes the recruitment of specialized immune cells, such as lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils into the CNS (216). CNS viral infections can lead to permanent neurologic damage and psychiatric disorders. Indeed, multiple viruses including Zika virus, West Nile virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have been associated with Guillain‐Barre syndrome and memory deficits (217, 218, 219, 220). Therefore, modulating the microglial recruitment of the infiltrating antigen‐specific lymphocytes is crucial to eliminate the virus from infected cells while limiting damage that may have long‐term detrimental consequences to the CNS. In light of that, a recent study by Brown et al has indicated the gut microbiota as a mediator for the protective function in mice intracranially infected with the neurotropic JHM strain of mouse hepatitis virus (JHMV), a mouse model of viral‐induced neurologic disease (221). Although GF mice initially have lower viral titers and increased CNS infiltrating Tregs during the acute phase of infection, the viruses are later persistently present in the CNS of GF mice while being undetectable in the SPF controls at that point, which is accompanied with worsened clinical symptoms. In addition, GF mice show enhanced neuronal damage and demyelination in the spinal cord, which can be linked to the lack of the anti‐inflammatory Tregs in GF mice during the chronic demyelinating phase of disease (221). Furthermore, the authors showed that the recruitment of the Tregs is not mediated by an intrinsic direct effect of the microbiota on T‐cell development, but rather microglia‐mediated through upregulation of antigen presentation machinery, which is regulated by gut microbiota‐derived TLR4 ligands (221).

Schistosomiasis, a globally neglected tropical disease, is a prevalent parasitic disease which plagues more than 240 million people in 76 countries in the world. The main pathogenic factor of schistosomiasis is the parasite eggs (222). Neuroschistosomiasis (NS), referring to schistosomal involvement of the CNS, is a severe form of presentation of schistosomiasis, where patients usually suffer from headache, vomiting, dizziness, convulsions, and paralysis. Schistosoma japonicum (S. japonicum), prevalent in Southeast Asia, mainly affects the brain (encephalic schistosomiasis japonicum) (223, 224). A recent study has shown that CNS macrophages including microglia play a role in forming granulomas that isolate and neutralize the infecting parasite eggs (225). Interestingly, another study utilizing mice with S. japonicum ova‐induced granulomas has shown alterations in the intestinal barrier and the gut microbiota composition upon infection (226). The authors reported an increased beta diversity, higher abundance of Akkermansia, and reduced Lactobacillus and Desulfovibrio in S. japonicum infected mice (226). These observed alterations have potential for use as biomarkers but could also have an association to the microglial phenotype in NS.

Future perspectives

The crucial impact of gut microbiota on immune cells is well established. Of outstanding interest is the question how various species‐, host‐, and tissue‐specific factors next to environmental factors including the microbiota can shape CNS diseases via microglia, the never resting tissue macrophages of the CNS (227, 228). Increasing evidence has linked alterations of the gut microbiota and bacterial‐derived molecules on the outcome of various CNS diseases. Bacteria‐derived AHR ligands and SCFAs are known signaling molecules modeling microglial properties and thereby potentially contribute to various CNS diseases in animal models and human patients (13). One complicating aspect is the fact that the composition of the gut microbiota and microglia also exhibits sexually dimorphic properties. Thus, the underlying signaling pathways are partially known and need characterization in future studies. Moreover, the current gut‐brain research mainly addresses bacterial populations of the microbiota, however, recent advances in microbiome sequencing techniques will help emphasize the role of other microbes which influence the gut homeostasis and potentially modulate the host’s immune and nervous systems (229). Finally, therapeutic approaches targeting the gut microbiota, including prebiotic, probiotic, and FMT strategies, have shown promising results for a variety of GIT and CNS disorders in preclinical and clinical models and could timely encompass microglia‐driven pathologies (230, 231, 232).

Author Contributions

OM wrote the manuscript and designed the figures. DE supervised and edited the manuscript. All authors listed approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the GF team at the institute of Neuropathology, University of Freiburg, namely, Charlotte Mezö, Jana Neuber, Janika Sosat, Nikolaos Dokalis, and Thomas Blank as well as the involved MD students, for the supportive team spirit and the great work in the last years. DE is supported by the DFG (SFB/TRR167). We thank Anaelle Dumas for proofreading the manuscript.

References

- 1. Metchnikoff E, Mitchell PC (1910) The Prolongation of Life, p, xxviii, 1 l. New York & London: G. P. Putnam's Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Luca F, Shoenfeld Y (2019) The microbiome in autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 195:74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gordo I (2019) Evolutionary change in the human gut microbiome: from a static to a dynamic view. PLoS Biol 17:e3000126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT (1997) Colonic microflora: nutrition and health. Nutrition 13:476–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu HJ, Wu E (2012) The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes 3:4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stokholm J, Blaser MJ, Thorsen J, Rasmussen MA, Waage J, Vinding RK et al (2018) Maturation of the gut microbiome and risk of asthma in childhood. Nat Commun 9:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Linehan JL, Harrison OJ, Han SJ, Byrd AL, Vujkovic‐Cvijin I, Villarino AV et al (2018) Non‐classical immunity controls microbiota impact on skin immunity and tissue repair. Cell 172:784–796.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weis M (2018) Impact of the gut microbiome in cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases. Clin Sci (Lond) 132:2387–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cryan JF, O'Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, Sandhu KV, Bastiaanssen TFS, Boehme M et al (2019) The microbiota‐gut‐brain axis. Physiol Rev 99:1877–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK (2016) The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell 167:915–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoyles L, Snelling T, Umlai U‐K, Nicholson JK, Carding SR, Glen RC et al (2018) Microbiome–host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood–brain barrier. Microbiome 6:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braniste V, Al‐Asmakh M, Kowal C, Anuar F, Abbaspour A, Toth M et al (2014) The gut microbiota influences blood‐brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci Transl Med 6:263ra158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mezö C, Mossad O, Erny D, Blank T (2019) The gut‐brain axis: microglia in the spotlight. Neuroforum 25:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erny D, Prinz M (2017) Microbiology: gut microbes augment neurodegeneration. Nature 544:304–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Prinz M, Jung S, Priller J (2019) Microglia biology: one century of evolving concepts. Cell 179:292–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prinz M, Erny D, Hagemeyer N (2017) Ontogeny and homeostasis of CNS myeloid cells. Nat Immunol 18:385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L et al (2015) Tissue‐resident macrophages originate from yolk‐sac‐derived erythro‐myeloid progenitors. Nature 518:547–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kierdorf K, Erny D, Goldmann T, Sander V, Schulz C, Perdiguero EG et al (2013) Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1‐ and Irf8‐dependent pathways. Nat Neurosci 16:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S et al (2010) Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 330:841–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Masuda T, Sankowski R, Staszewski O, Böttcher C, Amann L, Sagar, et al (2019) Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of mouse and human microglia at single-cell resolution. Nature 566:388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matcovitch-Natan O, Winter DR, Giladi A, Vargas Aguilar S, Spinrad A, Sarrazin S et al (2016) Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science 353:aad8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Varol D, Mildner A, Blank T, Shemer A, Barashi N, Yona S et al (2017) Dicer deficiency differentially impacts microglia of the developing and adult brain. Immunity 46:1030-1044.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kierdorf K, Prinz M (2017) Microglia in steady state. J Clin Invest 127:3201–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F (2005) Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 308:1314–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S et al (2005) ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci 8:752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kettenmann H, Kirchhoff F, Verkhratsky A (2013) Microglia: new roles for the synaptic stripper. Neuron 77:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Derecki NC, Katzmarski N, Kipnis J, Meyer-Luehmann M (2014) Microglia as a critical player in both developmental and late-life CNS pathologies. Acta Neuropathol 128:333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Szulzewsky F, Pelz A, Feng X, Synowitz M, Markovic D, Langmann T et al (2015) Glioma-associated microglia/macrophages display an expression profile different from M1 and M2 polarization and highly express Gpnmb and Spp1. PLoS One 10:e0116644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jordão MJC, Sankowski R, Brendecke SM, Sagar, Locatelli G, Tai Y-H et al (2019) Single-cell profiling identifies myeloid cell subsets with distinct fates during neuroinflammation. Science 363:eaat7554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, Fatimy RE et al (2017) The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity 47:566–581.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK et al (2017) A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell 169:1276–1290.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD et al (2015) Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523:337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rothhammer V, Borucki DM, Tjon EC, Takenaka MC, Chao CC, Ardura-Fabregat A et al (2018) Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites. Nature 557:724–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Erny D, Hrabe de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski O, David E et al (2015) Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci 18:965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thion MS, Low D, Silvin A, Chen J, Grisel P, Schulte-Schrepping J et al (2018) microbiome influences prenatal and adult microglia in a sex-specific manner. Cell 172:500–516.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK et al (2008) Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:16767–16772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Soliman ML, Rosenberger TA (2011) Acetate supplementation increases brain histone acetylation and inhibits histone deacetylase activity and expression. Mol Cell Biochem 352:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Levenson JM, O'Riordan KJ, Brown KD, Trinh MA, Molfese DL, Sweatt JD (2004) Regulation of histone acetylation during memory formation in the hippocampus. J Biol Chem 279:40545–40559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim HJ, Leeds P, Chuang D-M (2009) The HDAC inhibitor, sodium butyrate, stimulates neurogenesis in the ischemic brain: HDAC inhibition and cell proliferation. J Neurochem 110:1226–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garcez ML, de Carvalho CA, Mina F, Bellettini-Santos T, Schiavo GL, da Silva S et al (2018) Sodium butyrate improves memory and modulates the activity of histone deacetylases in aged rats after the administration of d-galactose. Exp Gerontol 113:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stecher B, Chaffron S, Kappeli R, Hapfelmeier S, Freedrich S, Weber TC et al (2010) Like will to like: abundances of closely related species can predict susceptibility to intestinal colonization by pathogenic and commensal bacteria. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Klein SL, Flanagan KL (2016) Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 16:626–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hanamsagar R, Alter MD, Block CS, Sullivan H, Bolton JL, Bilbo SD (2017) Generation of a microglial developmental index in mice and in humans reveals a sex difference in maturation and immune reactivity: HANAMSAGAR et al. Glia 65:1504–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lenz KM, McCarthy MM (2015) A starring role for microglia in brain sex differences. Neuroscientist 21:306–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schwarz JM, Sholar PW, Bilbo SD (2012) Sex differences in microglial colonization of the developing rat brain. J Neurochem 120:948–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. B Grishina Irina. Hormonal and Cell Signaling Pathways in Genital Development. Endocrinology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2012;01(3). 10.4172/2161-1017.1000e109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Strandwitz P (2018) Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res 1693(Pt B):128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Ratan RR (2016) Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett 625:56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Iqbal K, del C. Alonso A, Chen S, Chohan MO, El‐Akkad E, Gong C‐X et al (2005) Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1739:198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]