Abstract

Chemical risk in hospital settings is a growing concern that health professionals and supervisory authorities must deal with daily. Exposure to chemical risk is quite different depending on the hospital department involved and might origin from multiple sources, such as the use of sterilizing agents, disinfectants, detergents, solvents, heavy metals, dangerous drugs, and anesthetic gases. Improving prevention procedures and constantly monitoring the presence and level of potentially toxic substances, both in workers (biological monitoring) and in working environments (environmental monitoring), might significantly reduce the risk of exposure and contaminations. The purpose of this article is to present an overview on this subject, which includes the current international regulations, the chemical pollutants to which medical and paramedical personnel are mainly exposed, and the strategies developed to improve safety conditions for all healthcare workers.

Significance for public health.

Chemical risk in hospital settings is a growing concern that health professionals and supervisory authorities must deal with daily; acute and chronic exposure to commonly used compounds such as formaldehyde, organic solvents, anesthetic gases and anticancer drugs may lead to severe health effects for medical and paramedical personnel. This paper describes several aspects of chemical risk assessment in hospital settings by focusing both on regulatory aspects and monitoring strategies.

Key words: Occupational medicine, risk assessment, environmental monitoring, biological monitoring, sampling methods

Introduction

Occupational exposure of healthcare workers to hazardous chemicals in hospital settings may negatively affect health and quality of life, and greatly differs depending on the type of clinical unit and specific job involved.1,2 Chemical exposure in hospital environments may occur as acute intoxication or be the result of chronic and time-extended exposure of workers to low doses of contaminants. It can lead to damage to the nervous, hematopoietic, or reproductive systems,3 and a potential relationship with neoplastic pathologies has been recently underpinned.4

In recent years, increasing attention has been focused on chemical risk prevention, which includes strategies aimed at protecting operators from both accidental and chronical exposure. Biological monitoring (BM) of workers and environmental monitoring (EM) of working areas are among the most effective actions that can effectively improve chemical risk management. Aim of this article is to provide an overview of the most common chemical pollutants to which medical and paramedical staff can be professionally exposed to, and the different strategies that can be used to improve chemical risk management.

International regulations

The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EUOSHA) was established in the European Union in 1994, with the aim of improving European workplaces safety, productivity and health.5 An important milestone in chemical risk management in workplaces was set by European Union regulation n. 1907/2006, concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and restriction of CHemical products (REACH).6 This latter deals with the production and use of chemicals and their potential impacts on human health and environment. The REACH is also considered as a model in non-European countries such as South Korea. The Act on Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and restriction of CHemicals, established in 2015 and named K-REACH, is the Korean version of the regulation and aligns with the European model.7

Preventive measures for workers must refer to the Good Manufacturing Practice and Good Laboratory Practice.8,9 In these guidelines, specific suggestions for each class of compounds are continuously updated, according to novel classifications. Formaldehyde (FA), as an example, has changed from “suspected causing cancer” agent to “may cause cancer” on January 2016.10

Italian regulation about safety in workplaces was first described in Legislative Decree (Lgs. D.) n. 626,11 which follows the European Union (EU) specific directives. Later, Lgs. D n. 626 was updated by the European reference legislation,12 which provides general guidelines for the management of workers health prevention. The analysis of the individual risk factors (physical, chemical, biological) was described in the already mentioned REACH and its last update EU Regulation n. 1272/2008 (CLP - Classification Labeling Packaging).13

In the United States, workers safety is managed by two federal agencies, the National Institute for Safety and Health (NIOSH), and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), created in accordance with the “Occupational Safety and Health Act” signed on 29 December 1970.14 OSHA is a regulatory agency that periodically revises safety and health standards, while NIOSH was established to help ensure safety and healthy working conditions, especially for what concerns the development of guidelines for work injuries prevention and related diseases.14,15 In addition, the Environmental Protection Agency,16 an independent executive agency of the government of the United States, deals with regulations concerning environment appraisal and protection. EPA, through the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA or TOSCA) issued in 1976, regulates the introduction of new or existing substances by assessing their chemical risk.17

Environmental and biological monitoring

Occupational exposure to chemical agents should be evaluated, when possible, by a combined approach involving both environmental monitoring (EM) and biological monitoring (BM).18

Environmental monitoring involves the collection of one or more measurements aimed at identifying and quantifying the presence, in a specific environment, of potentially harmful pollutants. 19,20 EM allows evaluating workers effective exposure to chemicals and building a risk map by: i) Quantifying exposure to chemical hazards and evaluating the most advanced methodologies available to limit their dispersion; ii) Activating emergency control procedures to contain and mitigate the effects of acute exposure events; iii) Observing trends of exposure and pollution in workspaces; iv) Developing safety strategies, based on scientific data presented in literature.

Quantitative data achieved in the EM should be critically evaluated based on the threshold limit values (TLVs) defined for each pollutant. TLVs are the maximum environmental concentrations of a compound to which a person can be subjected without adverse health effects, even in case of a prolonged exposure, and are established combining data derived from both epidemiological data related to the industrial field, and experimental research. However, it should be underlined that EM and TLVs fail to evaluate the effective amount of chemicals that permeate through skin, airways or epithelia, which may be responsible of causing acute or chronic harmful events in healthcare workers.21

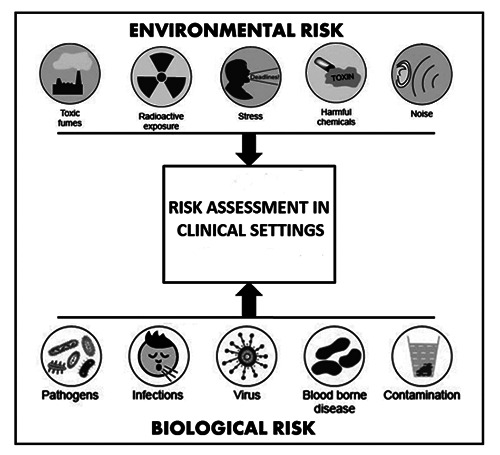

Figure 1.

Main aspects contributing to environmental and biological risk in clinical settings.

TLVs for airborne pollutants should consider the dimensional mass fraction of the compound analyzed, which can be classified as follows:

inhalable fraction, collected in any part of the respiratory tract.

thoracic fraction, collected in the lung and along gas exchange region.

respirable fraction, collected in the gas exchange region.

Nowadays, many standardized methods for the measurement in work settings of toxic chemical agents are available; conversely, direct methods to evaluate trans-dermic contamination are not always validated and few standardized procedures for the direct measurement of dermal exposure have been discussed so far.19 Therefore, when possible, BM is a critical tool to evaluate the effective absorption of chemical toxic compounds.

BM can be defined as “a systematic continuous or repetitive activity for collection of biological samples for analysis of concentrations of pollutants, metabolites or specific non-adverse biological effect parameters for immediate application, with the objective to assess exposure and health risk to exposed subjects, comparing the data observed with the reference level and — if necessary — leading to corrective actions”.22 In BM, it is possible to analyse specific biological indicators (BI), which may be considered direct markers of a real or potential exposure condition.23

BIs can be different according to the biological matrix (urine, blood, tissues, exhaled air, etc.), organ or tissue in which they originate and/or accumulate (kidney, liver, nervous system, etc.) and depending on the specific chemical-physical characteristics (volatility, hydro-liposolubility, etc.) of the compound/s of interest.

BIs can be divided into:

Biological exposure indicators (BEIs)

Biological response (or effect) indicators (BRIs)

Biological susceptibility indicators (BSIs).

A BEI can be an exogenous compound, its metabolite, or a product of its interaction with a target molecule or cell. BEIs are specific and often allow comparing values measured in exposed workers with those of a non-exposed population.23-25 Biological response indicators rely on the identification and quantification of the biological effects that are produced in target tissues, such as chromosomal aberrations or genetic mutations in somatic cells.23-25

Biological Susceptibility Indicators are biomarkers related to mechanisms of susceptibility to chemical agents and can be divided into toxic-kinetic and toxic-dynamic BSI. These indicators relate on the single organism reaction to an exogenous compound. 23-25

Limit values have also been set for BIs. Noteworthy, these values are generally defined by the Conference of American Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH)26 and were initially established relying on the levels of chemical pollutants present in the chemical industry.

However, they may not be eligible to assess actual exposure to lower concentrations used for example in hospital settings, which can still be harmful for exposed healthcare workers.

Principal pollutants in healthcare facilities

In hospitals and other healthcare facilities, the attention is usually focused on preventing the biological risk to avoid nosocomial diseases and accidental infections. However, healthcare workers are frequently exposed to several types of harmful compounds and, among them, chemical risk is often underestimated (Figure 1). Some studies showed a higher frequency of pathologies in hospitals where air quality was judged unsatisfactory compared to those where air quality standards were respected.27 Nevertheless, the guarantee of high air quality in hospitals remains a poorly developed field, both nationally and internationally.

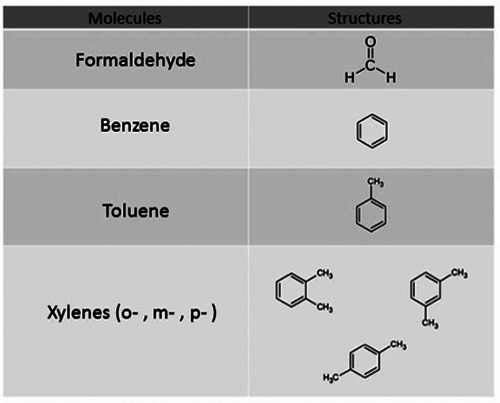

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and several other toxic chemicals (i.e., chemotherapeutic agents, xylenes and anaesthetic gases as an example) routinely used in healthcare settings and clinical laboratories (Figures 2 and 3) may cause adverse health effects on exposed people,28 which are different according to inter-individual variabilities that may influence pollutant diffusion, neutralization and excretion.20 Airborne pollutants, based on their physical status and mass, are classified in aeriform and particulate, which leads to different absorption rates by inhalation, lung retention times, and alveolar diffusion.19

Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde (FA) is a colourless, acrid-smelling VOC used for tissue fixation in anatomic pathology laboratories, and can cross-link with several endogenous organic compounds, such as proteins and nucleic acids, causing irreversible modifications of these molecules.29-32 At room temperature FA is gaseous and, consequently, mostly absorbed by inhalation and deposited in the upper respiratory tract. In addition, as an aqueous solution of formalin, skin exposure is also possible. The great reactivity of FA toward lipids, proteins and nucleic acids is responsible for most observed toxic effects. Acute or chronic toxic effects are strictly time- and concentration-dependent: exposure to 0.3-1 ppm (partper- million) in the environment cause skin, ocular and upper respiratory tract irritation, as well as headache, sleep disorders and fatigue, while exposure up to 4 ppm is associated to serious respiratory tract irritations. Asthma or nasopharyngeal cancers have also been reported.33 The Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) for formaldehyde are set at 300 part-per billion (ppb; 0.370 mg/m3) by the ACGIH.26 However, several studies demonstrated that these limits are often unattended during many procedures, such as autopsies. 34-36 Bono and co-workers showed that during histological samples preparation, workers were exposed to air concentrations of FA above 66 μg/m3, which seemed to be responsible for malondialdehyde- deoxyguanosine adducts (M1-dG), a biomarker of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation.36 Costa and co-workers have screened by comet assay the presence of chromosomal aberrations and DNA damage in human peripheral blood lymphocytes of 84 workers exposed to FA. The data obtained showed a potential health risk at concentrations higher than 0.38 ppm of FA.37 Starting December 2009, it has become mandatory to limit FA exposure levels to protect workers health. As a result, formaldehyde exposure has been further limited setting two-time limit values: the short-term OEL (15-min reference period) at 0.2 ppm and the 8-h working day OEL at 0.4 ppm.21

Several BIs have been investigated for the BM of healthcare workers exposed to FA: complete blood counts, evaluation of sister chromatid exchange, comet-assay on blood and buccal swab. While the possibility that inhaled FA may be present in biological fluids in significant concentrations needs to be further investigated, quantification of urinary FA at the end of the work shift is so far the most used test.38-41

Xylene

Xylene, a mixture of three organic isomers of dimethylbenzene, is a colorless liquid with a sweet and aromatic odor that can be smelled at 1 ppm, widely used for elimination of paraffin traces from histological samples before DNA staining or extraction.42 Acute toxicity after exposure to low concentrations of xylene includes skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation; however, massive inhalation can cause central nervous system depression (from headache to coma and death), pulmonary oedema and respiratory arrest.43 Long-term exposure can produce anemia, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, cardiac abnormalities with electrocardiogram modifications, dyspnea, and cyanosis.44 In pregnant women, exposure to xylene increases the probability of spontaneous abortions. Short-term OELs are set at 100 ppm, and 8-hour OELs at 50 ppm.45

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of common volatile organic compounds (VOCs) used in clinical settings.

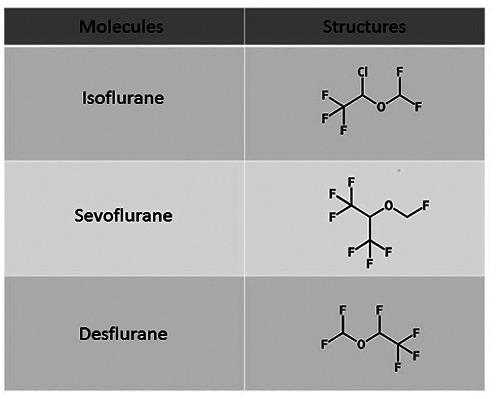

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of common anesthetic gases used in clinical settings.

Anesthetic gases

The first gaseous anesthetic agent used was nitric oxide in 1844. Subsequently, the use of diethyl ether and FA was approved for most surgical procedures. In 1950, modern halogenated or fluorinated inhalation anesthetic gases were introduced in the clinical practice. Halothane, a member of this class, is by far the most used anesthetic gas, along with nitrogen oxide.46 Nowadays, new inhalation anesthetics such as isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane (Figure 3) are used, alone or in combination with nitrogen oxide. Halogenated inhalants cause a rapid induction and recovery of anesthesia and are associated with an early post-operative mobilization because of their low liquid/gas partition coefficient.47

Since 1967, several studies showed that exposure to anesthetic agents, including halogenated can cause adverse effects on exposed workers.48-52 Occupational exposure to residual anesthetic gas concentrations may produce headache, dizziness, lethargy, fatigue, memory problems, neuro-behavioral changes.53-55 Studies performed on animal models indicates that chronic exposure to anesthetic gases can lead to miscarriages and congenital malformations; 47,53,56-59 Popova and co-workers. reported fetal resorption in rats even at very low concentrations (9 ppm).60

Several bio-monitoring studies have suggested the existence of a strong relationship between exposure to halogenated anesthetic gases and the risk of genotoxicity for surgery room staff. It has been observed that nitric oxide can interfere with vitamin B12 and irreversibly deactivate methionine synthase in CNS.61,62 Some studies also report effects of teratogenicity or increase in miscarriages in nitric oxide exposed women. A higher prevalence of congenital anomalies in the offspring of women professionally exposed during pregnancy and spontaneous abortions in women pregnant with exposed men have also been reported.63,64 For these reasons, it is important to monitor workers exposed to anesthetic gases by both EM of chemicals in exhaled air and BM of compounds in urine.65-67 Several studies have highlighted a good correlation between measured amounts of unmodified anesthetic gases in urine and in breathing air; these studies have proposed to use the same OELs for both BM and EM.68-70 Other authors suggested instead the evaluation of the urinary concentration of anesthetic gases metabolites.48,66,71,72

Accepted limits for halogenated substances are 2 ppm when used alone and 0.5 ppm when in combination with nitrous oxide, as suggested by NIOSH.15 The ACGIH set the Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) for nitrous oxide at 50 ppm26 while the Italian Health Department established the biological exposure limits at 27 mg/L for urinary nitrous oxide and 3.32 mg/L for urinary isoflurane, equivalent to environmental levels of 50 and 2 ppm, respectively. 73 To the best of our knowledge, no TLV are currently present for sevoflurane or other halogenated anaesthetic gases.

Anticancer drugs

Anticancer drugs (ADs) are used for the treatment of solid and hematologic tumors and are classified based on their action mechanism; however, most of them do not show specific selectivity towards cancer cells and thus have an intrinsic cytotoxicity on normal cells.74 Consequently, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has identified ADs as “potential carcinogens” or “carcinogens” agent for humans.75

Anticancer drugs toxicity has been known for decades and include effects such as liver, kidney, gastric, dermatological and haemopoietic damages.76 Antineoplastic drugs are generally irritating agent for mucous membranes, and they can cause local toxic effects (phlebitis, allergies) and systemic effects (anaphylactic shock and organ toxicity). Cellular necrosis, with lesions that may cause ulcers variable in severity and extension are also reported.77 According to IARC, it is possible that ADs can cause cancer in patients treated for non-oncologic pathologies; a well-known example of this, is the use of immunosuppressive drugs for organ transplants.78 Furthermore, new tumors formation, unrelated to primary pathology, has been reported in patients with solid cancers in treatment with ADs, especially in acute myeloid leukaemia.79 Finally, teratogenic effects on the fetus may occur in ADs exposed uterus.80

The risks for healthcare workers exposed to ADs have been known since the 70s, even in case of accidental exposure.81,82 Chronic exposure to small amounts of ADs in healthcare workers might cause rashes, allergic reactions, or headaches,83 and longterm effects including genomic instability and increased risk of reproductive dysfunctions.84-86 Increased AD levels were found in urine samples of nurses from oncology units compared to other wards especially during work shifts.82 Anticancer drugs can be inhaled or adsorbed through skin; cutaneous absorption has been observed for cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate, also after the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). This might be related to the permeability of latex gloves to these molecules. In addition, cyclophosphamide has a very low vapor pressure and laminar flow hood cannot retain volatilized cyclophosphamide molecules that can pass through the large filter pores.87 Another source of occupational exposure is the domiciliary intravenously or subcutaneously administration of chemotherapeutic agents (a practice that is currently discouraged). In this case, major risks can arise from air expulsion from the syringe before drug administration and by drug leaking from connectors or vials. For these reasons, EM and BM are both required for the correct management of chemical risk prevention in personnel working in close contact to antineoplastic drugs, such as laboratories, hospitals and pharmaceutical companies. In EM, AD quantification on surfaces and objects is carried out using wipes and pad tests.88

Sampling methods in BM

Toxic compounds can be adsorbed by skin contact, inhalation, and/or ingestion; it mainly depends on the chemical-physical properties of the molecules and the type of exposure. These characteristics also influence tissue distribution, as highly water-soluble pollutants distribute in all body fluids, while lipophilic substances will likely concentrate in lipid-rich tissues (i.e., the brain). Tissue characteristics such as composition, pH, permeability and vascularization also influence chemicals absorption in the body.

Compounds can be eliminated, as intact compounds or their metabolites, through various pathways, such as breathing, urine, fecal, and by lactation way. Exogenous compounds undergo metabolic modifications of their chemical structure, such as oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis or a combination of these, often followed by conjugation with an endogenous substrate. Conjugation is a key-step for exogenous substrates excretion and include reaction with glucuronic acid, amino acids, acetylation, sulphate conjugation and methylation. Metabolism and excretion of intact compounds, their metabolites and the ratio between these molecules are influenced by several inter-individual variabilities such as age, diet and health status, presence of known polymorphisms that affect metabolism, body hydration, or time after chemical exposure. 89,90 These variables, together with the pharmacokinetic properties of chemicals, must be taken into consideration during the initial set-up of an analytical method for the BM of a specific BI.

Different biological matrixes (e.g., blood, urine, breath) may be selected based on expected molecule concentration, its kinetics and the difficulty related to the sample collection (urine and breath are the less invasive samples to collect).91 Sampling times is also important and strongly depends on the biological half-life of the compound of interest and on the time interval during which the compound has been handled (e.g., sampling before, after or at any time during the working shift). Sampling of molecules with a short half-life may give indications on a recent exposure and should be performed quickly after a potential contact, while monitoring of long half-life indicators can provide information about a chronic exposure.90 The analysis of exhaled air (breath test) is an attractive non-invasive technique for the determination of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) derived from professional exposure and might be used for many toxic agents. Although exhaled air is a simpler matrix compared to urine and blood, the use of breath test in BM shows some challenges - mainly related for example to the extremely low concentration of the analyzed compounds - which hampers its diffusion into routine practice.92

Urine samples are used to measure contaminating chemicals, metals, and hydrophilic metabolites; however, concentrations may vary based on urine volume and composition and this may lead to analytes dilution.89-91 Therefore, normalization of excreted compounds should be performed by using a molecule present at a constant concentration regardless of the urinary volume collected, such as creatinine. Some volatile chemicals, such as formaldehyde for example, are eliminated in the kidney by diffusion, which is driven by the urine/blood distribution coefficient; thus, in this case, normalization of the concentration value is not required.

Blood is considered as the best biological matrix because the majority of BIs are present in the blood for a certain amount of time and data normalization is not required, but venipuncture is an invasive procedure that must be performed only by trained personnel.

Sampling methods in EM

Environmental Monitoring activities in workplaces are carried out to determine the concentration levels of pollutants, according to their chemical-physical and toxicological characteristics, and to identify the sources of emission. Environmental monitoring responds to: i) surveillance activities following confirmed or potential pollution situations; ii) complaints raised by exposed workers; iii) surveillance activities to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies previously adopted; iv) the need for specific information to facilitate decision-making processes when assessing the exposure of workers with reference to the different residence times in a given environment; v) the verification of compliance through guidelines established by competent authorities.

In this framework, a preliminary qualitative evaluation is required to identify the pollutants or their chemical class. For the identification and subsequent quantization of environmental pollutants, two approaches are currently available: direct measurement methods and indirect measurement methods.89

Direct measurement methods use devices and instruments to quantify gases, vapors or aerosols without user manipulation and without sending sample to an external laboratory. These devices allow an immediate evaluation without the need to preserve or manipulate the sample later. Direct measurement systems generally consist of a sampling system, a detector, an electronic processing system, a display and a memory device. Although they allow for an immediate evaluation of the concentration pollutant over time, they suffer of several drawbacks such as measuring range, detection limit, precision, accuracy, resolution, interference and so on. Indirect measurements methods involve collecting air samples in the investigated environment which are then analyzed in laboratory. According to monitoring objectives, short-term samplings (sampling time between a few minutes and several hours) can be planned, generally carried out with canisters93 or active sampling on adsorbent cartridges94 or long-term samplings (time sampling from a few hours to several days), generally performed with diffusive samplers.95

Canisters are stainless steel containers with a variable volume from 400 ml to 15 L, subjected to an electro-passivation process to reduce the presence of chemically active polar sites and subsequently coated on the internal surface with a thin layer of chemically silica bonded. The canister, after being cleaned, is placed under vacuum and is ready for sampling, which can be instantaneous or mediated. The instantaneous sampling is performed by simply opening the valve placed at the closure of the canister, while the “mediated” one is carried out by applying an orifice calibrated at the opening of the canister.93 Active sampling, with tubes containing adsorbent materials, is carried out with appropriate systems where the air is first drawn into the tube through a sampling pump, calibrated to the required flow rate. Pollutants react with the specific substrate causing chromatic variations in a concentrationdependent manner or can be trapped and, at the end of the sampling, the tubes are stored until desorbed and analyzed in laboratory. Once the sampling phase is complete, the tubes must be closed with the appropriate caps and stored in glass or metal containers in refrigerated systems maintained at controlled temperature until analysis.

Passive devices are used for long-term measurement through a diffusion air process according to Fick’s laws of diffusion. Diffusive samplers have been found to be useful and cost-effective alternatives to conventional pumped samplers. The passive sampler consists of an adsorbent cartridge inserted inside a diffusive body, whereby analyte molecules diffuse along the concentration gradient, from the ambient concentration, which corresponds to the outer part of the sampler, to the effective zero concentration, present on the surface of the absorbent within the sampler.95 For both active and passive method, at the end of the sampling, the pollutants are chemically or thermally desorbed from the support and transferred for the analytical determination, which can be subsequently carried out using various techniques, such as gas chromatography, ion chromatography or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).95,96

The air quality of operating rooms is usually monitored using a real-time or an integrated air sampling. In real-time methods, the concentration of anesthetics is directly measured with a portable gas-chromatograph equipped with a multiple sampling system. In integrated air sampling, air is collected on an appropriate adsorbent tube and analyzed by gas-chromatography in laboratory.15

Methods of analysis

The selection of a suitable analytical method is driven by the characteristics of each investigated pollutant. For VOCs, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) suggests the use of direct measurement instruments equipped with a flame ionization (FID) or photoionization (PID) detector specific for each type of pollutant.97 For VOCs analysis, “continuous” automatic analyzers are widely used; these all-in-one instruments collect the air sample and perform a real-time analysis. Generally, a specific device is needed for each analyte. For air sampling, it is important to define instrument volumetric flow, time of sampling and sampled air volume. However, gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC/MS) remains the gold standard for accurate and simultaneous quantification of a wide range of VOCs. In this case, gaseous substances are collected from the environment or adsorbed on special supports, eluted with a gaseous mobile phase and analyzed based on mass/charge ratio for each analyte. For EM of volatile solvents, such as FA, specific and dedicate equipment is also available.98

Chromatography has significantly improved both EM and BM. Compared to classic immunometric or radiolabeling techniques, chromatography is faster and cheaper. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with different types of detectors, such as Photodiode array, Fluorimeter and other, is available in almost all healthcare facilities and is employed for the simultaneous detection and quantification of many compounds. The use of liquid chromatography to monitor compounds potentially harmful to health extends to an ever-increasing number of compounds, such as solvents,99,100 commonly used drugs101 and cytotoxic agents.102 Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has a high selectivity and sensitivity for the simultaneous analysis of several pollutants and chemicals from complex matrices, such as biological fluids, even at very low concentrations.103 The great versatility and sensitivity of mass spectrometry render this technique suitable for both BM and EM. UHPLC-MS/MS high selectivity allows for the simultaneous analysis of a great number of compounds in complex matrices, such as biological fluids, even at very low concentrations. 104

Inhalation of dust or drug droplets has long been considered the main route of accidental exposure to toxic agent for hospital personnel. On the contrary, recent studies indicate skin direct contact as the main route of exposure, especially through the hands and forearms of nurses and technicians who often wear uniforms with short sleeves. Exposure can occur also through accidental ingestion or for hand-to-mouth contamination.105 Therefore, wipe test is currently the preferred method to check workspace surfaces and operator gloves. According to this method, surfaces, gloves or even the gowns of the operators are rubbed with wipes impregnated with a solvent. Wipes are then squeezed, and the desorbed solvent is analyzed by previous described chromatographic methods. 88

Conclusions

In recent years, the interest in prevention has been constantly increasing, diversifying itself from the simple concept of “protection”, viewed as the whole set of measures and instruments aimed at protecting from chemical hazard accidental exposure. Prevention processes involving a routine monitoring of the presence and level of potentially toxic substances, can reduce the risk of work injuries derived from chemicals. Furthermore, increasing attention should be focused on the long-term damage caused by chronic exposure to contaminants. Safety and health conditions of all operators operating in health facilities should be the ultimate goal to look for.

Healthcare workers are frequently exposed to accidental biological and chemical risks as occasional contamination or prolonged exposure. Contaminations are often detected in hospitals, even when trained staff rigorously carry out all safety procedures and monitoring practices. For this reason, healthcare facilities need to routinely monitor and continuously improve risk management plans and protective equipment, making monitoring simpler, faster, and less expensive. In addition, the discovery of new-targeted therapies for the treatment of solid and hematologic tumors requires continuous updates in risk management plans and biohazard risk prevention that should be directed not only to operators, but also to all potentially exposed subjects, such as patients’ close relatives or volunteers. The long-term monitoring and systematic records could help identifying the risks related to toxic agent exposure. Therefore, EM and BM in healthcare facilities should not only be a project plan merely following national and/or internationally regulations or a solely execution of standard procedures, but a concrete tool for an effective protection of all workers involved in health management.

References

- 1.McDiarmid MA. Chemical hazards in health care: high hazard, high risk, but low protection. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1076:601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vecchio D, Sasco AJ, Cann CI. Occupational risk in health care and research. Am J Ind Med 2003;43:369-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart-Evans JL, Sharman A, Isaac J. A narrative review of secondary hazards in hospitals from cases of chemical selfpoisoning and chemical exposure. Eur J Emerg Med 2013;20:304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leso V, Ercolano ML, Cioffi DL, Iavicoli I. Occupational exposure and breast cancer risk according to hormone receptor status: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Agency for Safety and Health at work. Available from: https://osha.europa.eu/en/about-eu-osha [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Commission. EC regulation N 1907/2006 (2006) of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha S, Seidle T, Lim KM. Act on the Registration and Evaluation of Chemicals (K-REACH) and replacement, reduction or refinement best practices. Environ Health Toxicol 2016;31:e2016026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Commission Health and Consumers Directorate-General. Guidelines for Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). Public Health and Risk Assessment Medicinal Product – quality, safety and efficacy. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Commission. EC directive 2004/10/EC (2004). Council Directive 2004/10/EC on the harmonisation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to the application of the principles of good laboratory practice and the verification of their applications for tests on chemical substances. [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Commission. EC regulation N° 605/2014 (2014) of the European Parliament and of the Council amending, for the purposes of introducing hazard and precautionary statements in the Croatian language and its adaptation to technical and scientific progress, Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Italian Government. Legislative Decree 1994 n.626, G.U. n265 (November 12,1994). [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Commission. EC directive 89/391/EEC (1989). Council Directive 89/391/EEC on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work. (89/391/EEC). [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Commission. EC regulation N° 1272/2008 (2008) of the European Parliament and of the Council on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSH Act of 1970. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/lawsregs/oshact/toc [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Occupational Exposure Sampling Strategy Manual. Cincinnati: NIOSH. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Regulatory Reform - Laws & Regulations. 2017. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/regulatory-reform [Google Scholar]

- 17.Environmental Protection Agency. Summary of the toxic substances control act. TSCA; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakubowski M. Biological monitoring versus air monitoring strategies in assessing environmental-occupational exposure. J Environ Monit 2012;14:348-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marć M, Tobiszewski M, Zabiegała B, et al. Current air quality analytics and monitoring: a review. Anal Chim Acta 2015;853:116-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts SM, Rohr AC, Mikheev VB, et al. Influence of airborne particulates on respiratory tract deposition of inhaled toluene and naphthalene in the rat. Inhal Toxicol 2018;30:19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tynkkynen S, Santonen T, Stockmann-Juvala H. A comparison of REACH-derived no-effect levels for workers with EU indicative occupational exposure limit values and national limit values in Finland. Ann Occup Hyg 2015;59:401-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zielhuis RL. Recent and potential advances applicable to the protection of workers’ health - Biological Monitoring. II. Assessment of toxic agents at the workplace - Roles of ambient and biological monitoring. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1984. p. 84-94. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manno M. Viau C in collaboration with Cocker J et al. Biomonitoring for occupational health risk assessment (BOHRA). Toxicol Lett 2010;192:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Technical guides. Elemental speciation in human health risk assessment / authors: Postoli P., et al. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutti A, De Palma G, Manini P, et al. Linee guida per il monitoraggio biologico. Pavia: PIME; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). Documentation of the threshold limit values and biological exposure indices, 7th Ed. Cincinnati: ACGIH Signature Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dascalaki E, Gaglia AG, Balaras C, Lagoudi A. Indoor environmental quality in Hellenic hospital operating rooms. Energ Build 2009;41:51-60. [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBouf RF, Virji MA, Saito R, et al. Exposure to volatile organic compounds in healthcare settings. Occup Environ Med 2014;71:642-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cipolla M, Izzotti A, Ansaldi F, et al. Volatile organic compounds in anatomical pathology wards: Comparative and qualitative assessment of indoor airborne pollution. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritzsche FR, Ramach C, Soldini D, et al. Occupational health risks of pathologists--results from a nationwide online questionnaire in Switzerland. BMC Public Health 2012;12:1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall A, Harrington JM, Aw TC. Mortality study of British pathologists. Am J Ind Med 1991;20:83-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa S, Pina C, Coelho P, et al. Occupational exposure to formaldehyde: Genotoxic risk evaluation by comet assay and micronucleus test using human peripheral lymphocytes. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2011;74:1040-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maison A, Pasquier E. [Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité – Technical guides. Le point des connaissances sur le formaldehyde].[in French]. ED 5032. 1-4. 3ème Edition. Paris: Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.D'Ettorre G, Criscuolo M, Mazzotta M. Managing formaldehyde indoor pollution in anatomy pathology departments. Work 2017;56:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azari MR, Asadi P, Jafari MJ, et al. Occupational exposure of a medical school staff to formaldehyde in Tehran. Tanaffos 2012;11:36-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bono R, Romanazzi V, Munnia A, et al. Malondialdehydedeoxyguanosine adduct formation in workers of pathology wards: the role of air formaldehyde exposure. Chem Res Toxicol 2010;23:1342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa S, Carvalho S, Costa C, et al. Increased levels of chromosomal aberrations and DNA damage in a group of workers exposed to formaldehyde. Mutagenesis 2015;30:463-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sancini A, Rosati MV, De Sio S, et al. Exposure to formaldehyde in health care: an evaluation of the white blood count differential. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2014;36:153-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin D, Guo Y, Yi J, et al. Occupational exposure to formaldehyde and genetic damage in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of plywood workers. J Occup Health 2013;55:284-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peteffi GP, Antunes MV, Carrer C, et al. Environmental and biological monitoring of occupational formaldehyde exposure resulting from the use of products for hair straightening. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2016;23:908-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen GD, Larsen ST, Wolkoff P. Recent trend in risk assessment of formaldehyde exposures from indoor air. Arch Toxicol 2013;87:73-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalantari N, Bayani M, Ghaffari T. Deparaffinization of formalin- fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks using hot water instead of xylene. Anal Biochem 2016;15:507:71-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenzie LM, Witter RZ, Newman LS, Adgate JL. Human health risk assessment of air emissions from development of unconventional natural gas resources. Sci Total Environ 2012;424:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niaz K, Bahadar H, Maqbool F, Abdollahi M. A review of environmental and occupational exposure to xylene and its health concerns. EXCLI J 2015;14:1167-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inoue O, Seiji K, Kawai T, et al. Excretion of methylhippuric acids in urine of workers exposed to a xylene mixture: comparison among three xylene isomers and toluene. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1993;64:533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yılmaz S, Çalbayram NÇ. Exposure to anesthetic gases among operating room personnel and risk of genotoxicity: A systematic review of the human biomonitoring studies. J Clin Anesth 2016;35:326-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tankò B, Molnàe L, Fülesdi B, Molnàr C. Occupational hazards of halogenated volatile anesthetics and their prevention: review of the literature. J Anesth Clin Res 2014;5:1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guirguis SS, Pelmear PL, Roy ML, Wong L. Health effects associated with exposure to anaesthetic gases in Ontario hospital personnel. Br J Ind Med 1990;47:490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen EN, Bellville JW, Brown BW. Anesthesia, pregnancy and miscarriage. A study of operating room nurses and anesthetists. Anesthesiology 1971;35:343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wrońska-Nofer T, Nofer JR, Jajte J, et al. Oxidative DNA damage and oxidative stress in subjects occupationally exposed to nitrous oxide (N(2)O). Mutat Res 2012;731:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferguson LR. Chronic inflammation and mutagenesis. Mutat Res 2010;690:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brodsky JB, Cohen EN. Adverse effects of nitrous oxide. Med Toxicol 1986;1:362-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Byhahn C, Wilke HJ, Westpphal K. Occupational exposure to volatile anaesthetics: epidemiology and approaches to reducing the problem. CNS Drugs 2001;15:197-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scapellato ML, Mastrangelo G, Fedeli U, et al. A longitudinal study for investigating the exposure level of anesthetics that impairs neurobehavioral performance. Neurotoxicology 2008;29:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith FD. Management of exposure to waste anesthetic gases. AORN J 2010;91:482–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Basford AB, Fink BR. The teratogenicity of halothane in the rat. Anesthesiology 1968;29:1167-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wharton RS, Wilson AI, Mazze RI, et al. Fetal morphology in mice exposed to halothane. Anesthesiology 1979;51:532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cassiano da Rosa A, Beier SL, Oleskovicz N, et al. Effects of exposure to halothane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane on embryo viability and gestation in female mice. Semin-Cienc Agrar 2015;36:871-81. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baeder C, Albrecht M. Embryotoxic/teratogenic potential of halothane. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1990;62:263-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Popova S, Virgieva T, Atanasova J, et al. Embryotoxicity and fertility study with halothane subanesthetic concentration in rats. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1979;23:505-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krajewski W, Kucharska M, Pilacik B, et al. Impaired vitamin B12 metabolic status in healthcare workers occupationally exposed to nitrous oxide. Br J Anaesth 2007;99:812-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sardas S, Izdes S, Ozcagli E, et al. The role of antioxidant supplementation in occupational exposure to waste anaesthetic gases. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2006;80:154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujinaga M, Baden JM, Yhap EO, Mazze RI. Reproductive and teratogenic effects of nitrous oxide, isoflurane, and their combination in Sprague-Dawley rats. Anesthesiology 1987;67:960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olfert SM. Reproductive outcomes among dental personnel: a review of selected exposures. J Can Dent Assoc 2006;72:821-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jafari A, Bargeshadi R, Jafari F, et al. Environmental and biological measurements of isoflurane and sevoflurane in operating room personnel. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2018;91:349-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Accorsi A, Valenti S, Barbieri A, et al. Proposal for single and mixture biological exposure limits for sevoflurane and nitrous oxide at low occupational exposure levels. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2003;76:129-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sackey PV, Martling CR, Nise G, Radell PJ. Ambient isoflurane pollution and isoflurane consumption during intensive care unit sedation with the Anesthetic Conserving Device. Crit Care Med 2005;33:585-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Accorsi A, Morrone B, Domenichini I, et al. Urinary sevoflurane and hexafluoro-isopropanol as biomarkers of low-level occupational exposure to sevoflurane. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2005;78:369-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Imbriani M, Ghittori S, Pezzagno G, Capodaglio E. Anesthetic in urine as biological index of exposure in operating- room personnel. J Toxicol Environ Health 1995;46:249-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kovatsi L, Giannakis D, Arzoglou V, Samanidou V. Development and validation of a direct headspace GC-FID method for the determination of sevoflurane, desflurane and other volatile compounds of forensic interest in biological fluids: application on clinical and post-mortem samples. J Sep Sci 2011;34:1004-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scapellato ML, Carrieri M, Maccà I, et al. Biomonitoring occupational sevoflurane exposure at low levels by urinary sevoflurane and hexafluoroisopropanol. Toxicol Lett 2014;231:154-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haufroid V, Gardinal S, Licot C, et al. Biological monitoring of exposure to sevoflurane in operating room personnel by the measurement of hexafluoroisopropanol and fluoride in urine. Biomarkers 2000;5:141-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Italian Department of Health. Circular n. 5, March 14, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Castiglia L, Miraglia N, Pieri M, et al. Evaluation of occupational exposure to antiblastic drugs in an Italian hospital oncological department. J Occup Health 2008;50:48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lancharro PM, De Castro-Acuña Iglesias N, González- Barcala FJ, Moure González JD. Evidence of exposure to cytostatic drugs in healthcare staff: a review of recent literature. Farm Hosp 2016;40:604-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wahlang JB, Laishram PD, Brahma DK, et al. Adverse drug reactions due to cancer chemotherapy in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2017;8:61-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skarin AT. Atlas of diagnostic oncology: Systemic and mucocutaneous reactions to chemotherapy. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. p. 721-36. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moretti M, Bonfiglioli R, Feretti D, et al. A study protocol for the evaluation of occupational mutagenic/carcinogenic risks in subjects exposed to antineoplastic drugs: a multicentric project. BMC Public Health 2011;11:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Italian Department of Health. Action August 5,1999. Official Journal n. 236, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Topçu S, Beşer A. Oncology nurses' perspectives on safe handling precautions: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse 2017;53:271-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Petit M, Curti C, Roche M, et al. Environmental monitoring by surface sampling for cytotoxics: a review. Environ Monit Assess 2017;189:52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Falck K, Gröhn P, Sorsa M, et al. Mutagenicity in urine of nurses handling cytostatic drugs. Lancet 1979;1:1250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boiano JM, Steege AL, Sweeney MH. Adherence to safe handling guidelines by health care workers who administer antineoplastic drugs. J Occup Environ Hyg 2014;11:728-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McDiarmid MA, Oliver MS, Roth TS, et al. Chromosome 5 and 7 abnormalities in oncology personnel handling anticancer drugs. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:1028-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Connor TH, Lawson CC, Polovich M, McDiarmid MA. Reproductive health risks associated with occupational exposures to antineoplastic drugs in health care settings: a review of the evidence. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:901-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Warembourg C, Cordier S, Garlantézec R. An update systematic review of fetal death, congenital anomalies and fertility disordes among health care workers. Am J Ind Med 2017;60:578-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sessink PJ, Trahan J, Coyne JW. Reduction in surface contamination with cyclophosphamide in 30 US hospital pharmacies following implementation of a closed-system drug transfer device. Hosp Pharm 2013;48:204-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Connor TH, Zock MD, Snow AH. Surface wipe sampling for antineoplastic (chemotherapy) and other hazardous drug residue in healthcare settings: Methodology and recommendations. J Occup Environ Hyg 2016;13:658-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Application of biological monitoring methods - Manual of analytical methods. 4th ed. Cincinnati: NIOSH; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Australian Government Department of Consumer and Employment Protection. Risk-based health surveillance and biological monitoring — guideline: Resources Safety. Department of Consumer and Employment Protection; Western Australia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Health and Safety Executive. Biological monitoring in the workplace: a guide to its practical application to chemical exposure. Richmond: Health and Safety Executive; 1997. Available from: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/hsg167.htm [Google Scholar]

- 92.Singh KD, Tancev G, Decrue F, et al. Standardization procedures for real-time breath analysis by secondary electrospray ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2019;19:4883-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McClenny WA, Holdren MW. Compendium method TO-15, determination of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in air collected in specially-prepared canisters and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Environmental Protection Agency, technical guides 1999. Available from: https://www3.epa.gov/ttnamti1/files/ambient/airtox/to-15r.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cucciniello R, Proto A, La Femina R, et al. A new sorbent tube for atmospheric NOX determination by active sampling. Talanta 2017;164:403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Motta O, Cucciniello R, La Femina R, et al. Development of a new radial passive sampling device for atmospheric NOx determination. Talanta 2018;190:199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cucciniello R, Proto A, Rossi F, et al. An improved method for BTEX extraction from charcoal. Anal Meth 2015;7:4811-5. [Google Scholar]

- 97.International Organization for Standardization. ISO 16000-2004. Indoor air - Part 1. General aspects of a sampling strategy. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sassine M, Picquet-Varrault B, Perraudin E, Chiappini L, et al. A new device for formaldehyde and total aldehydes realtime monitoring. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2014;21:1258-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Olmos V, Lenzken SC, López CM, Villaamil EC. High-performance liquid chromatography method for urinary trans, trans-Muconic acid. Application to environmental exposure to benzene. J Anal Toxicol 2006;30:258-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Inoue O, Seiji K, Suzuki T, et al. Simultaneous determination of hippuric acid, o-, m-, and p-methylhippuric acid, phenylglyoxylic acid, and mandelic acid by HPLC. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 1991;47:204-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ashfaq M, Noor N, Saif Ur Rehman M, et al. Determination of commonly used pharmaceuticals in hospital waste of Pakistan and evaluation of their ecological risk assessment. Clean Soil Air Water 2017;45:1500392. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Viegas S, Pádua M, Veiga AC, et al. Antineoplastic drugs contamination of workplace surfaces in two Portuguese hospitals. Environ Monit Assess 2014;186:7807-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gómez MJ, Petrović M, Fernández-Alba AR, Barceló D. Determination of pharmaceuticals of various therapeutic classes by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatographytandem mass spectrometry analysis in hospital effluent wastewaters. J Chromatogr A 2006;1114:224-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Izzo V, Charlier B, Bloise E, et al. A UHPLC-MS/MS-based method for the simultaneous monitoring of eight antiblastic drugs in plasma and urine of exposed healthcare workers. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2018;154:245-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Turci R, Sottani C, Spagnoli G, Minoia C. Biological and environmental monitoring of hospital personnel exposed to antineoplastic agents: a review of analytical methods. J Chrom B 2003;789:169–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]