Abstract

Bloodstream infections caused by nontyphoidal Salmonella are a major public health concern in Africa, causing ~49,600 deaths every year. The most common Salmonella enterica pathovariant associated with invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease is Salmonella Typhimurium sequence type (ST)313. It has been proposed that antimicrobial resistance and genome degradation has contributed to the success of ST313 lineages in Africa, but the evolutionary trajectory of such changes was unclear. Here, to define the evolutionary dynamics of ST313, we sub-sampled from two comprehensive collections of Salmonella isolates from African patients with bloodstream infections, spanning 1966 to 2018. The resulting 680 genome sequences led to the discovery of a pan-susceptible ST313 lineage (ST313 L3), which emerged in Malawi in 2016 and is closely related to ST313 variants that cause gastrointestinal disease in the United Kingdom and Brazil. Genomic analysis revealed degradation events in important virulence genes in ST313 L3, which had not occurred in other ST313 lineages. Despite arising only recently in the clinic, ST313 L3 is a phylogenetic intermediate between ST313 L1 and L2, with a characteristic accessory genome. Our in-depth genotypic and phenotypic characterization identifies the crucial loss-of-function genetic events that occurred during the stepwise evolution of invasive S. Typhimurium across Africa.

Subject terms: Molecular evolution, Phylogenetics, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Genome informatics, Phylogeny

Stepwise evolution of invasive Salmonella Typhimurium in Africa is defined using genotypic and phenotypic analyses of isolates collected over a 50-yr period.

Main

Over the past decade, bloodstream infections (BSI) caused by nontyphoidal Salmonella (NTS) have killed approximately 650,000 people globally1. Invasive NTS (iNTS) disease disproportionally affects immunocompromised individuals such as adults with human immunodeficiency virus and children under five years of age with malaria, malnutrition or severe anaemia living in lower-to-middle-income countries2. Recently, a systematic review established that Salmonella was the most frequently isolated pathogen in hospitalized patients diagnosed with community-onset BSI in Africa and Asia (2008 to 2018)3. The S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is responsible for approximately two-thirds of iNTS disease cases in Africa4, and consequently is a focal point for research.

The majority of S. Typhimurium isolated from BSI in Africa have sequence type ST3135. There are two distinct and tightly clustered lineages of ST313, which differ from each other by 455 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)5. ST313 lineage 1 (L1) and ST313 lineage 2 (L2) differ by 700 SNPs6 from ST19, which commonly causes gastrointestinal infections globally. The African ST313 L1 and L2 are genetically distinct from ST313 found in the United Kingdom and Latin America7,8.

It has been proposed that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) contributed to the success of ST313 lineages in Africa, with a large proportion of strains being multidrug resistant (MDR)9. Amongst S. Typhimurium ST313, chloramphenicol resistance is specifically found in L2, and is thought to have contributed to the clonal replacement of L1 by L2 prior to 2001, when chloramphenicol was the empirical treatment choice for suspected sepsis in Malawi6. Subsequently, chloramphenicol was replaced by the oral fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin for treatment of iNTS infections in several parts of Africa including Malawi. The third-generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone became the empirical therapeutic for suspected sepsis from 20059. More recently, variants of ST313 L2 with resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and ciprofloxacin or azithromycin have been identified in Malawi and the Democratic Republic of Congo, respectively10,11.

In addition to AMR, the ST313 lineages have accumulated loss-of-function mutations (genome degradation)12. Evidence of host adaptation in ST313 involved specific pseudogenes that inactivated gene function and modified metabolic and virulence phenotypes5,13–18. The functional relevance of genome degradation in ST313 has been investigated at the transcriptomic, proteomic and phenotypic levels for several key isolates5,13–17,19. To understand the evolutionary trajectory and epidemiological relevance of functional degradative events, a study of Salmonella genomes from a wide range of contemporary and historical isolates is required.

Here we study a large and up-to-date collection of ST313, revealing the stepwise evolution of S. Typhimurium causing BSI in Africa. We uncover a pan-susceptible lineage (ST313 L3) with a distinct genome-degradation pattern, which emerged in Malawi in 2016. Despite the recent appearance of ST313 L3 in clinics, our core and accessory genome analyses reveal it to be a phylogenetic intermediate between ST313 L1 and L2. We perform genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the key loss-of-function events that occurred along the evolutionary pathway of invasive S. Typhimurium across Africa.

Results

Assembling an informative collection of S. Typhimurium isolates

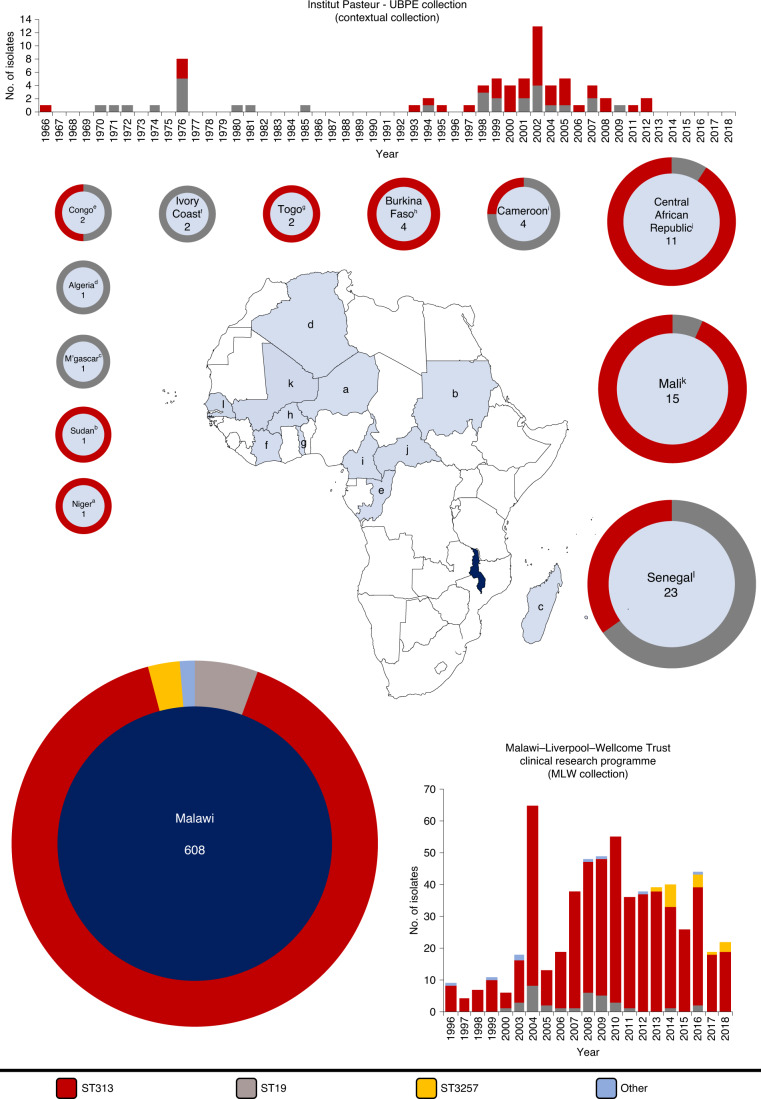

A combination of historical and contemporary S. Typhimurium bloodstream isolates was sampled from two sources (Fig. 1). The main dataset consisted of 608 human bloodstream isolates collected between 1996 and 2018 from the Malawi–Liverpool–Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme (MLW) in Blantyre, Malawi. To provide context, 72 human bloodstream isolates collected between 1966 and 2012 by the Unité des Bactéries Pathogènes Entériques, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France were also included. This contextual collection was derived from 13 countries in Africa, 1 in Europe and 1 in Asia. A description of the isolates is summarized in Fig. 1, details of sequencing quality control are available in Supplementary Table 1 and the complete metadata, including genome accession numbers, are in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1. Bloodstream isolates of Salmonella Typhimurium used in this study.

Isolates were collected from either the Unité des Bactéries Pathogènes Entériques of the Institut Pasteur Centres (n = 72, light blue) or the MLW Clinical Research Center (n = 608, dark blue). Bar graphs show the number of isolates of different sequence types collected by centre per year. Donut charts indicate the proportion of sequence types collected per country and show the total number of isolates from each location in the centre. Note that only isolates from African countries (M’gascar, Madagascar; Congo, Republic of the Congo) are shown in donut plots. Letters in superscript relate to the location on the map. The colour code is shown at the bottom of the figure.

Population structure of S. Typhimurium

To define the population structure of S. Typhimurium currently causing BSI in Africa, we explored the relationship of the 680 S. Typhimurium genomes from the MLW and contextual collections. The two predominant sequence types causing BSI in Malawi were ST313 (n = 549) and ST19 (n = 34). A small number of isolates (n = 25) were typed as ST313 single-locus variants (ST3257 (n = 17), ST2080 (n = 3), ST302 (n = 3), ST4200 (n = 1) and ST4274 (n = 1)). The contextual dataset contained two sequence types, ST313 (n = 43) and ST19 (n = 29). In sum, ST313 isolates originated from nine African countries (Fig. 1). Previous genome-based analyses of the African ST313 epidemic included isolates from eastern and central Africa6,11. Here, by including several Western Africa countries, we have expanded the known geographic range of ST3136,8,11,20–23 to include Cameroon, Central African Republic, Niger, Senegal, Sudan and Togo.

To investigate population structure, a core genome maximum-likelihood phylogeny was constructed, and cluster designation was performed. Three major ST313 clusters, four ST19 clusters and a small number of miscellaneous strains were identified (Extended Data Fig. 1). Multi-locus sequence type variants formed discrete sublineages. The three ST313 clusters were clonal, with cluster 1 and 2 corresponding to previously defined lineages (ST313 L1 and L2)5.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Dataset maximum likelihood core genome SNP phylogeny.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny based on the core genome SNP alignment of strains used in this study. Background shading on phylogeny represents cluster designation (rHierBAPs) and additional metadata is represented as adjacent colour strips. Note that Malawi-Liverpool Wellcome Clinical Research Center is abbreviated to MLW and Institute Pasteur Unité des Bactéries Pathogènes Entériques Contextual Collection is abbreviated to IP. Figure visualised using iTOL69.

The genomes of contemporary isolates revealed that a third lineage has been circulating in Malawi since 2016 (ST313 L3; Fig. 2). Characterization based on long-read sequencing showed that ST313 L3 strain BKQZM9 had a circular chromosome (4.8 Mb) with 99.98% sequence identity to the ST313 L2 reference strain D235805.

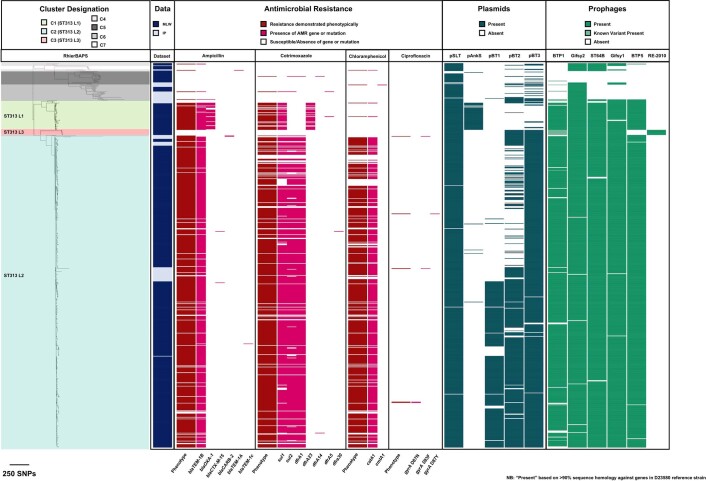

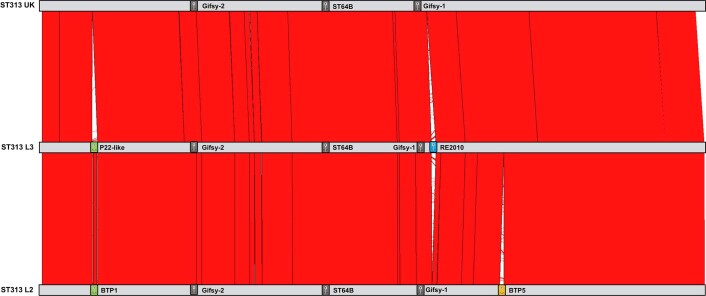

Fig. 2. The four major ST313 clusters have different prophage and plasmid repertoires.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny demonstrating the population structure of ST313 L1, L2 and L3. Approximate location of UK lineages is indicated schematically (Extended Data Fig. 2) due to the diversity of isolates. Prophage and plasmid repertoire of the reference strain for each lineage are shown (dark grey indicates presence; light grey represents absence). Reference isolates used were A130 (ST313 L1), D23580 (ST313 L2), BKQZM9 (ST313 L3) and U2 (UK strains). Red blocks represent the extent of conservation between lineage reference genomes, with white gaps indicating missing regions. Coloured squares on the pSLT plasmid represents different AMR cassettes. *P22-like prophage is absent in UK reference (U2), but present in some UK strains.

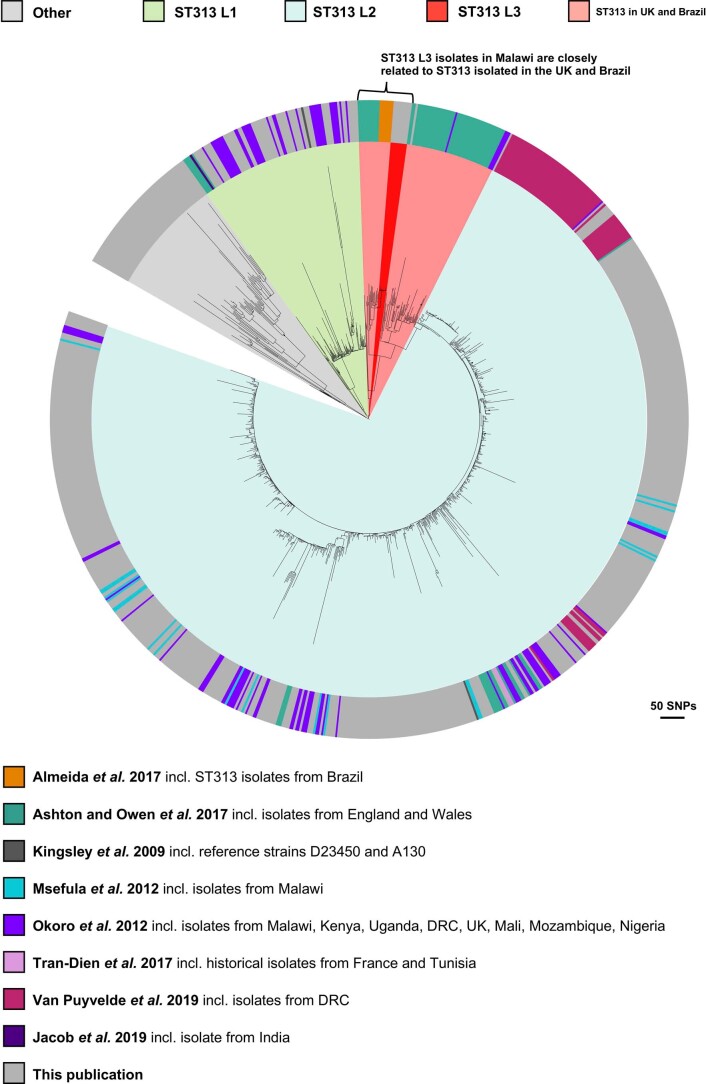

To fully contextualize ST313 L3, we constructed a core gene maximum-likelihood phylogeny, including previously published ST313 genomes (Supplementary Table 3), alongside the current dataset (Extended Data Fig. 2). ST313 L3 forms a monophyletic cluster within a group of ST313 strains isolated in the United Kingdom and Brazil7,8, raising the possibility of an international transmission event. ST313 L3 isolates are closely related, with a maximum pairwise distance of 16 SNPs. To determine whether ST313 L3 represents an outbreak in Malawi, it would be necessary to combine genome-based information with details on time, person and place. Patient-level GPS data were unavailable, therefore the geospatial distribution of ST313 L3 is currently unknown.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Contextual maximum likelihood core gene SNP phylogeny.

Maximum likelihood phylogeny based on the core gene SNP alignment of strains in this study in the context of published ST313 genomes5–8,11,21,22,89. Background shading on phylogeny represents cluster designation (rHierBAPs). Outer ring provides details on the original publication. Grey represents this publication. Figure visualised using iTOL69.

Accessory genome of S. Typhimurium ST313 lineages

To understand the relationship between ST313 L3 and other ST313 lineages, we examined the accessory genome in the context of population structure (Fig. 2). All lineages carried the virulence plasmid pSLT24, and ST313 L2 additionally contained plasmids pBT1, pBT2 and pBT3, consistent with previous studies5,17. ST313 L1 carried a previously unreported 8,274-base pair (bp) plasmid, sharing 99.27% sequence identity with pAnkS25 (GenBank NC_010896.1), which encodes the LsoA–LsoB toxin–antitoxin proteins. This toxin–antitoxin system functions as a bacteriophage exclusion system in Salmonella26 (Supplementary Discussion 1). ST313 L3 strain BKQZM9 contained the 95 kb plasmid (pSLT), a 1,975-bp plasmid (pBT3) and a 2,556-bp plasmid (pBT2, identified using short-read data only). Thus, the plasmid profile of ST313 L3 shared more similarity with ST313 L2 than other lineages, but lacked pBT1 (Fig. 2, S1).

A pairwise comparison of reference strains BKQZM9 (ST313 L3), D23580 (ST313 L2) and U2 (the representative UK-isolated ST313 strain) (Extended Data Fig. 3) revealed chromosomal differences involving the prophage repertoires (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Information). The common S. Typhimurium prophages Gifsy-1, Gifsy-227 and ST64B28 were identified in all three ST313 African lineage reference strains. ST313 L3 carried a Fels-2-like prophage that was absent from the ST313 L2 and the UK-isolated ST313 representative, and shared 99.99% sequence identity to the prophage RE-201029 found in other extraintestinal Salmonella serovars, including a global outlier cluster of Salmonella Enteritidis30 and Salmonella Panama31,32 (Extended Data Fig. 3). Prophage BTP5 was absent from the ST313 L3 reference strain. BTP5 is associated with ST313 L1 and L233, but is generally absent from UK-isolated ST31320.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Chromosomal comparison of ST313 lineages.

Comparison of the complete genome sequences of ST313 lineage representatives generated using the Artemis Comparison Tool86. Reference isolates used; D23580 (ST313 L2), BKQZM9 (ST313 L3) and U2 (UK strains). The number of genes shared between D23580 and BKQZM9 was 4,529. An additional 167 genes were BKQZM9-specific, whereas 309 genes were exclusive to D23580, largely explained by differences in the prophage and plasmid repertoire of the two strains. Red represents sequence similarity and white represents regions absent. Prophage positions are represented as coloured boxes.

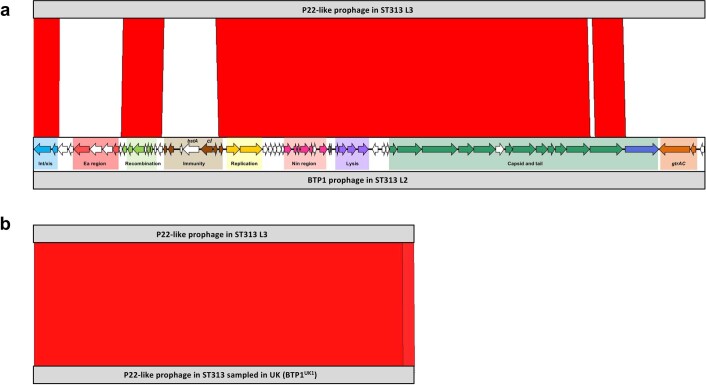

Prophage BTP1 was not found in ST313 L3, although a related P22-like prophage with 74% fragmented sequence identity to BTP1 occupied the same attachment site (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The P22-like prophage had almost identical replication, lysis and capsid genes to BTP1, differing only in the Ea, immunity, tail and gtr regions, and lacking the bstA34 gene. The ST313 L3 P22-like prophage carried the sieB gene, which encodes a superinfection exclusion phage immunity protein35. The SieB proteins of ST313 L3 and P22 were 92% identical, with the two proteins sharing 177 out of 192 amino acids. Carriage of a gene that mediates abortive phage infection could confer a selective advantage to ST313 L3, reflecting the functional role of the BTP1 prophage-encoded BstA virus defence protein in ST313 L234. BstA defends bacterial cells that carry BTP1 against exogenous attack by a variety of lytic phages, conferring a beneficial trait to ST313 L2 without sacrificing lytic autonomy34. Although BTP1 is absent from the UK reference strain U2, two UK-isolated ST313 strains (U15 and U87) carried a P22-like prophage with 99.96% sequence identity to the one found in ST313 L3 (Extended Data Fig. 4b). In summary, the prophage repertoire of ST313 L3 shares similarities with UK-isolated ST313.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Prophage BTP1 comparisons.

Comparison of P22-like prophage regions identified in ST313 lineages generated using the Artemis Comparison Tool86. Red represents sequence similarity and white represents regions absent. (a) shows the comparison between P22-like prophage in ST313 L3 (strain BKQZM9) and ST313 L2 (strain D23580). Prophage annotation is adapted from that shown in Owen et al., 201733, with different colours highlighting different prophage regions. (b) shows the comparison between P22-like prophage in ST313 L3 (strain BKQZM9) and a P22-like prophage in ST313 sampled in the UK.

Genomic epidemiology of AMR

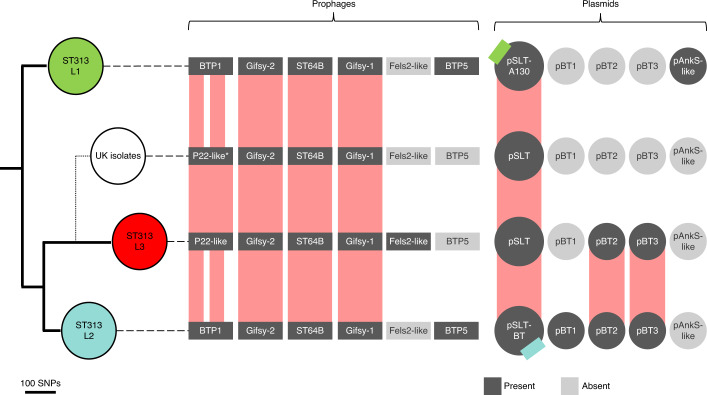

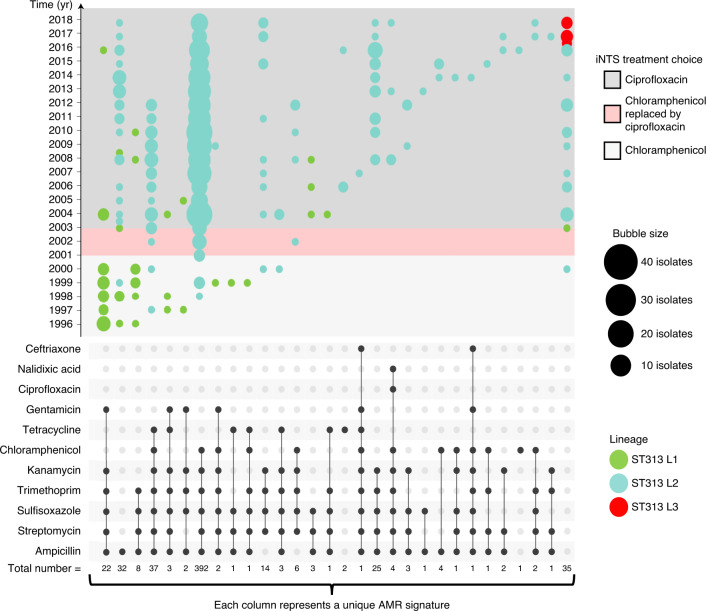

To obtain epidemiological insights into the emergence of ST313 lineages, we investigated the dynamics of AMR. The draft genome sequences of all 680 isolates were examined for genes and mutations that confer reduced susceptibility to antimicrobials (Supplementary Discussion 2). In total, 65% (n = 440) of isolates had an MDR genotype36. Among ST19 isolates, only 11% (7 out of 63) of isolates were resistant to at least 1 antimicrobial. However, among ST313 isolates, 94% of isolates were resistant to at least 1 antimicrobial. The number of chloramphenicol-resistant isolates of ST313 L2 have decreased over time, with 89.19% (n = 66 out of 74) before 2005, decreasing to 84.11% (n = 307 out of 365) between 2006 and 2015 and 65.28% (n = 47 out of 72) between 2016 and 2018 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, there have been changes in antimicrobial usage policy at the local level in Malawi during this timeframe, including the phased withdrawal of chloramphenicol from clinical practice beginning in 2001.

Fig. 3. Temporal AMR trends in S. Typhimurium lineages (1996–2018).

The combination matrix (bottom) depicts predicted AMR patterns of S. Typhimurium. Isolates collected before 1996 were sampled only sporadically, and thus were excluded from analysis. Within the combination matrix, dark grey circles indicate genome-predicted resistance and the vertical combination of grey circles represents the resistance profile. Total number of isolates with each resistance profile is indicated below the matrix. The combination matrix was created using the UpSetR package87. The bubble plot (top) depicts the relative number of isolates (bubble size) with each resistance profile (combination matrix) per year (y axis). Lineage assignments are shown using bubble colour to identify lineage-specific AMR trends. Local Malawi antimicrobial usage policy9 is highlighted in background colours overlaid on the timeline in the bubble plot. The bubble plot was created using R ggplot288.

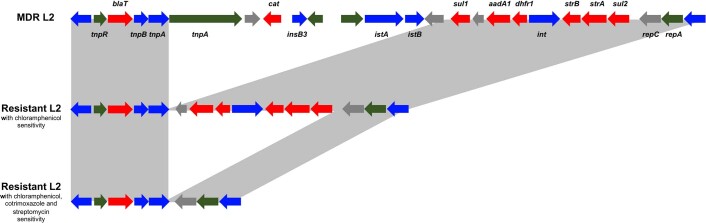

Overall, ST313 in this study had numerous genetic determinants of antibiotic resistance, with 29 different AMR genotype patterns involving 11 antimicrobials (Fig. 3). The AMR phenotype of ST313 L1 and L2 is encoded by resistance cassettes carried on a composite Tn21-like transposable element, inserted in the S. Typhimurium virulence plasmid pSLT5–7,14. The plasmid backbone of pSLT was present in all ST313 strains and we observed lineage-specific variation in the Tn21 insertion site, consistent with previous reports5. The Tn21-like region varied between isolates, reflecting the AMR profile (Extended Data Fig. 5). Plasmid pAnkSST313-L1 carried the blaTEM gene which mediated beta-lactam resistance of ST313 L1.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Examples of variation within the Tn21-like element.

Annotation of the resistance cassette carried on the Tn21-like element integrated into the Salmonella virulence plasmid pSLT-BT. Examples of variation in the Tn21-like element is shown for three different resistance profiles in ST313 L2, Grey boxes between annotations represents gene presence. Annotation is adapted from Kingsley et al., 20095, and shows antibiotic resistance genes (red), integrase or transposase (blue), pseudogenes (green) and other genes (grey).

ST313 L3 was pan-susceptible to all antimicrobials tested, both genotypically and phenotypically (Fig. 2), as were the UK-isolated ST31320. In contrast to L1 and L2, ST313 L3 did not carry an MDR cassette on the pSLT-BT plasmid (Extended Data Fig. 6). Phylogenetic reconstruction of the pSLT plasmid (Extended Data Fig. 7) reflected the core genome SNP-based phylogeny, demonstrating four phylogenetic clades (ST313 L1, L2, L3 and ST19). There was no evidence of a scar associated with excision of the Tn21-like transposable element around location 48,530 on the ST313 L3 pSLT plasmid.

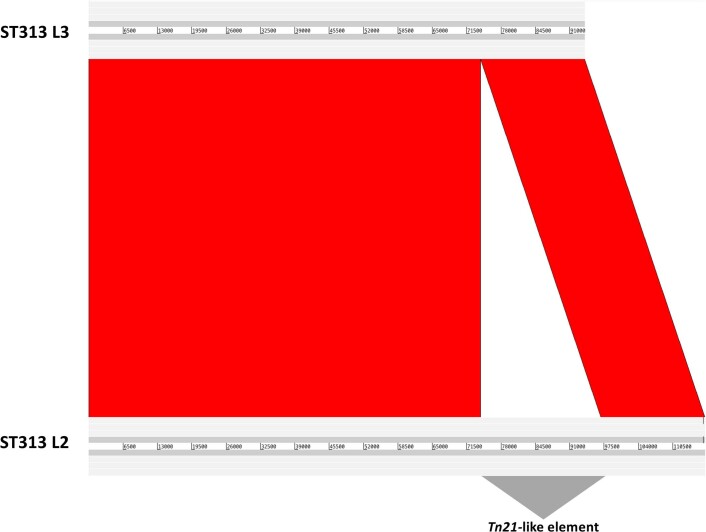

Extended Data Fig. 6. pSLT comparison of D23580 vs BKQZM9.

Comparison of the Salmonella virulence plasmid pSLT identified in ST313 L3 (BKQZM9) and ST313 L2 (D23580) generated using the Artemis Comparison Tool86. Red represents sequence similarity and white represents absent regions. The location of the Tn21-like element is indicated.

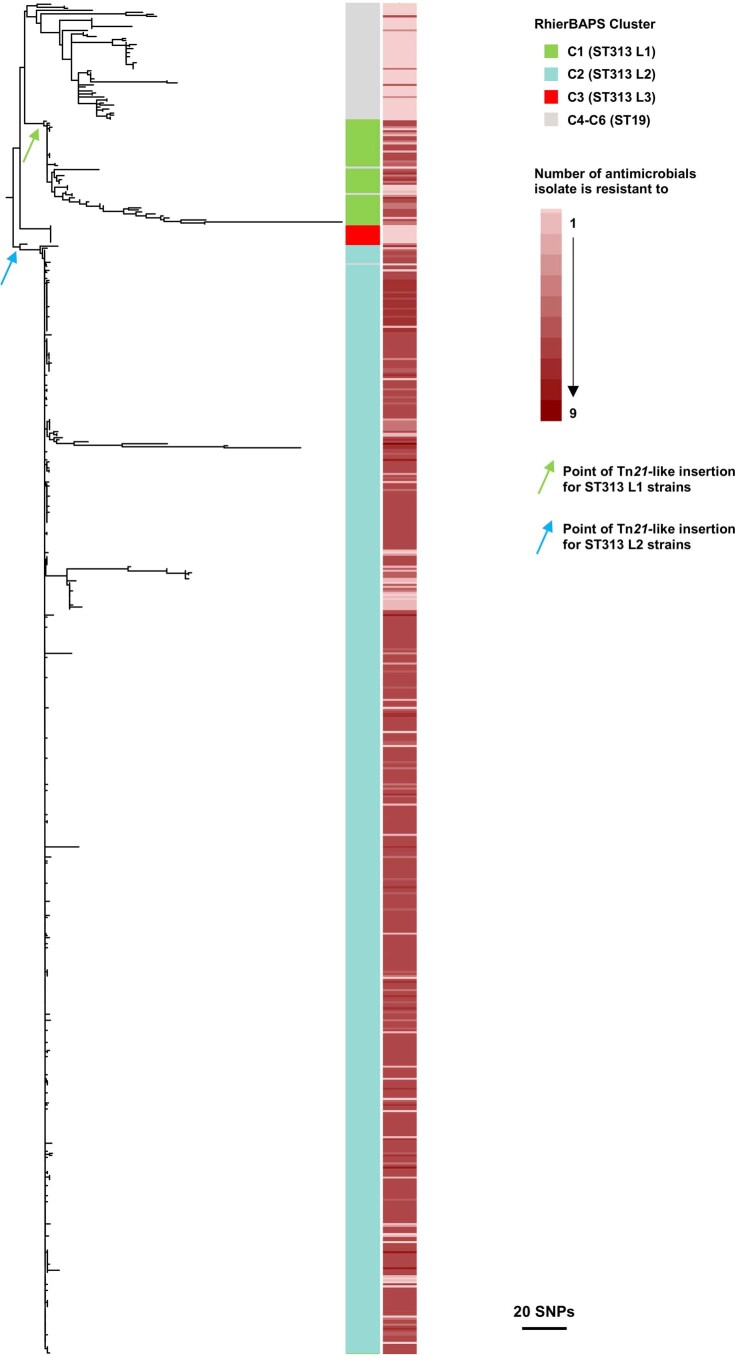

Extended Data Fig. 7. Phylogenetic reconstruction of pSLT plasmid.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing the population structure of the pSLT plasmid in ST19 and ST313 lineages. Colour strip from right to left; cluster assignment of each isolate and number of antimicrobials each isolate is resistant to. The likely point of insertion of the Tn21-like element is indicated for ST313 L1 strains (green arrow) and ST313 L2 strains (blue arrow).

Less than 1% (n = 5/180) of African S. Typhimurium ST313 L2 carried mutations associated with reduced fluoroquinolone susceptibility (for example, gyrA37), originating in Malawi (n = 3), Mali (n = 1) or Cameroon (n = 1). The GyrA proteins had either S83F, D87N or D87Y amino acid substitutions. All five strains were phenotypically susceptible to ciprofloxacin. Ongoing surveillance will be important for identification of strains with triple mutations which would confer full resistance to this clinically important antibiotic.

The evolutionary trajectory of S. Typhimurium ST313

Dates for lineage divergence were provided by Bayesian phylogenetic inference (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 8). The most-recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all ST19 and ST313 sampled in this study was from around ad 918 (95% highest posterior distribution (HPD) ad 570–1080) and the MRCA of all ST313 sampled in this study (Fig. 4, event 0) was from around ad 1566 (95% ad HPD 1271–1953). The incorporation of historical and diverse isolates that predate those used in previous phylodynamic analysis6,7 generates an older MRCA of ST313 lineages than previously described7 (around ad 1787). However, we note that the branch linked to the MRCA is deeply rooted in the phylogeny and the 95% HPD values reported here have a substantial range. A limitation of Bayesian analysis is that it relies upon a series of user-defined prior probability distributions that influence the estimation of tip dates (Methods).

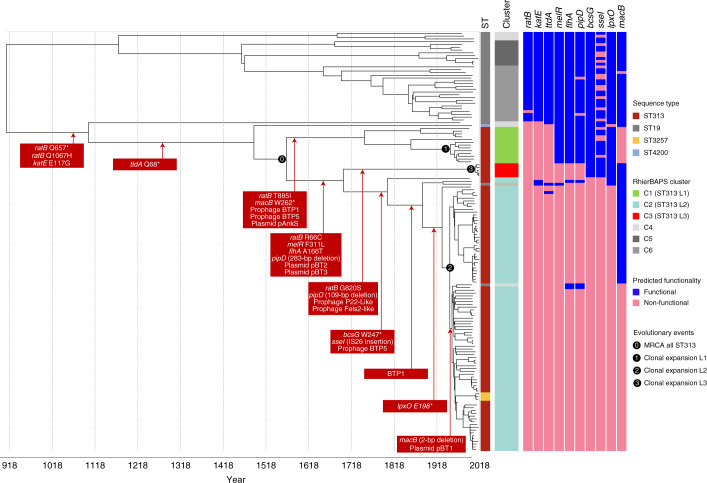

Fig. 4. Stepwise evolution of S. Typhimurium responsible for BSI in Africa.

Chronograph of 150 S. Typhimurium strains isolated from the bloodstream of human patients with iNTS disease. The choice of the 150 isolates from both the Malawian and contextual datasets is described in Methods. The figure shows a maximum clade credibility tree. Adjacent colour strips are as follows (from left to right); ST, lineage assignment (rHierBAPs) with the three major ST313 lineages highlighted in colour. Predicted functionality (Methods) is depicted as a colour strip for each gene and is based on whole-genome-based predictions of SNPs likely to play a functional role. Genome-degradation events that generate functionally relevant pseudogenes are displayed in red boxes overlying the chronograph. An asterisk represents a premature stop codon. The numbers in black circles indicate four key evolutionary events. Figure visualized using iTOL69.

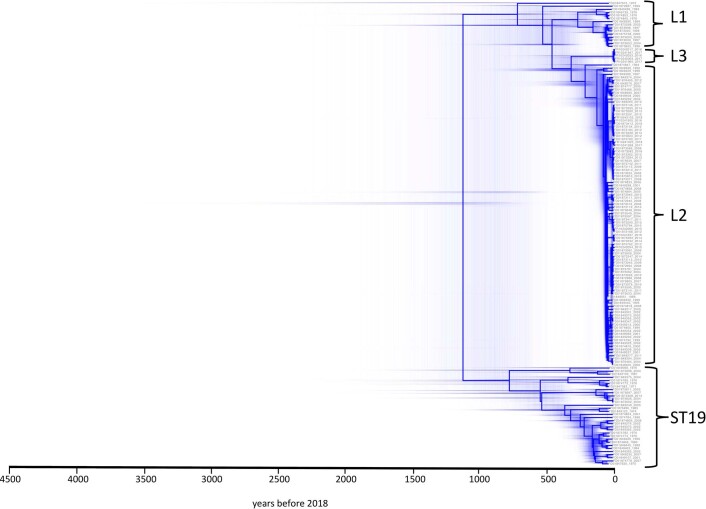

Extended Data Fig. 8. Distribution of possible hierarchies generated in BEAST analysis.

Chronograph of 150S. Typhimurium strains isolated from bloodstream of human iNTS disease patients. The figure displays the distribution of possible hierarchies and highlights uncertainty in the timeline. Figure was visualized using DensiTree74.

The MRCA of ST313 L1 dated to about ad 1794 (95% HPD ad 1738–1965), with Malawian ST313 L1 forming a discrete sublineage with an MRCA dating to around ad 1950 (95% HPD ad 1921–1986) (Fig. 4, event 1). The ST313 L2 MRCA (Fig. 4, event 2) dated to around ad 1948 (95% HPD ad 1929–1959). These MRCA estimates overlap with previous 95% HPD values for ST313 lineage dating6. The MRCA of ST313 L3 (Fig. 4, event 3) was ad 2007 (95% HPD ad 1998–2012), showing that the clonal expansion of ST313 L3 occurred in recent evolutionary history.

Phylodynamics of pseudogene formation in S. Typhimurium ST313

To explore the association of pseudogenization and invasive salmonellosis, we characterized the stepwise progression of functional gene loss associated with host adaptation that probably facilitated the ST313 epidemic in Africa (Methods). This phenomenon is exemplified by the timeline of pseudogene accumulation in ST313 L2 shown in Fig. 4.

Our discovery of ST313 L3 allowed the timeline of gene-degradation events to be scrutinized in more detail. For example, mutations in melR (F311L), flhA (A166T) and pipD (283-bp deletion) occurred prior to the divergence of ST313 L3 and ST313 L2, while the mutations in bcsG (W247*), sseI (IS26 insertion) and lpxO (E198*) preceded the clonal expansion of ST313 L2. A small number of gene-degradation events were associated only with ST313 L3, specifically an additional non-synonymous mutation in ratB (G820S) and a 109-bp deletion in pipD. Both mutations occurred in genes that had been pseudogenized earlier in evolutionary history, and so are unlikely to cause specific phenotypic changes. The macB, sseI and lpxO genes that were non-functional in ST313 L2 were functional in ST313 L3, as reported previously for the UK ST313 representative (U2)7. We recently reported the functional significance of the pseudogenization of macB for ST313 L218. The frameshift event that inactivated the macB gene occurred between ad 1948 and ad 1953 (95% HPD ad 1931–1963), representing the final stage in the evolution of ST313 L2 detected in our analysis (Fig. 4).

Function of evolutionarily important S. Typhimurium ST313 genes

To complement our genome-derived evolutionary insights, we linked a number of lineage-specific phenotypes to individual SNPs (summarized in Table 1 and detailed fully in Supplementary Table 4). For example, the KatE catalase protects bacteria from environmental oxidative stress, and shows a maximal activity in stationary phase cultures of S. Typhimurium ST1915. The E117G KatE mutation caused low level catalase activity in ST313 L1, L2, L2.1 and the UK-isolated ST3137,11,15. We report a similarly low activity in ST313 L3 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). Catalase is required for biofilm formation38, a phenotype associated with survival outside the host, leading to the suggestion that pseudogenization of katE in ST313 reflects adaptation to a restricted host range16.

Table 1.

Summary of the phenotypic impact of pseudogenes in ST313 lineages

| Gene Name | Description | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| ratB (STM2514) | Secreted outer membrane protein | Inactivation of ratB is associated with gut persistence in mouse model and is likely to have reduced the enteric potential of ST313 (ref. 14). |

| katE (STM1318) | Stationary phase catalase | Catalase activity is reduced across all ST313 L1 and L2 isolates7,15. We confirmed that ST313 L3 has a lower catalase activity than ST19. |

| ttdA (STM3355) | l(+)-tartrate dehydratase | l-tartaric acid and dihydroxyacetone cannot be used as sole carbon sources by ST313 L1 or L2 (ref. 14). We confirmed experimentally that ST313 L3 is unable to grow on l-tartaric acid as a sole carbon source. |

| melR (STM4297) | Melibiose operon response regulator | ST313 L2 cannot grow on melibiose as a sole carbon source17,82. We confirmed experimentally that ST313 L3 was unable to grow on melibiose as a sole carbon source. |

| flhA (STM1913) | Flagella biosynthesis protein | Comparison of the ST313 L2 D23580 flhA474 mutant to wild type shows that the A166T SNP carried by ST313 L2 and ST313 L3 causes reduced motility17. |

| pipD (STM1094) | Pathogenicity island encoded protein D | Although a causal relationship is unproven, the PipD effector protein of ST19 contributes to macrophage persistence in murine models14,17,43. |

| bcsG (STM3624) | Cellulose biosynthetic enzyme | Biofilm formation is impaired in ST313 L2 due to a mutation in bcsG15. Here we show that biofilm formation in ST313 L3 is also impaired. The genetic basis is unknown. |

| sseI (STM1051) | Type III secretion effector protein (SPI-2) | Studies in mice demonstrate that an accumulation of SNPs within the sseI gene of ST313 L2 increases the ability of the bacteria to disseminate rapidly from the gut to the draining lymph nodes16. |

| lpxO (STM4286) | Putative membrane-bound β-hydroxylase | We compared the lipid A of ST313 L2 (D23580) and ST19 (4/74) during growth in SPI-2-inducing media. By mass spectrometry, we confirmed that the lipid A of ST313 L2 lacks the LpxO-mediated modification associated with ST19. |

| macB (STM0942) | Putative ABC transport protein | MacAB is involved in oxidative stress resistance13 and antibiotic resistance to macrolides81. In ST313 L1 and L2, variants of the MacAB–TolC tripartite efflux pump affect replication in macrophages and influence fitness during colonization of the murine gastrointestinal tract18. |

Associated phenotypic data are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

The red, dry and rough (RDAR)-negative phenotype of ST313 L239 is caused by pseudogenization of bcsG15 and two nucleotide changes in the csgD gene promoter region39. ST313 L3 has an intermediate RDAR phenotype, with an incomplete wrinkling pattern (Supplementary Table 4). ST313 L3 has a functional bcsG gene and had the same csgD-associated −189 promoter mutation as ST313 L1 and L239. Our finding that ST313 L3 has lost traits required for stress resistance and biofilm formation is consistent with a reduced requirement for environmental survival and the mounting evidence for human-to-human transmission of ST31340,41.

S. Typhimurium ST19 relies on carbon metabolism to colonise the mammalian gastrointestinal tract42, whereas genes required for utilization of specific carbon sources, such as tartrate and melibiose, are not functional in ST313 lineages17. ST313 L3 was also unable to grow with tartrate or melibiose as a sole carbon source, consistent with the pseudogenization of the ttdA and melR genes in both ST313 L3 and ST313 L25,17 (Fig. 4).

Further evidence of genome degradation is provided by the pseudogenization of the genes ratB in all ST313 lineages, pipD in ST313 L2 and L3, and lpxO in ST313 L2. The PipD effector protein has been implicated in gastrointestinal pathogenesis of ST19, although a causal relationship has not been demonstrated43,44. The lpxO gene is pseudogenized by a stop codon in ST313 L25. LpxO hydroxylates lipid A, a modification required for virulence of S. Typhimurium ST1945. We used mass spectrometry to show that the lack of functional LpxO caused structural modifications of lipid A in ST313 L2 (Table 1, Supplementary Table 4). The functionality of the lpxO gene in ST313 L3, reflects the distinct evolutionary path of this lineage.

Invasiveness potential of ST313 L3

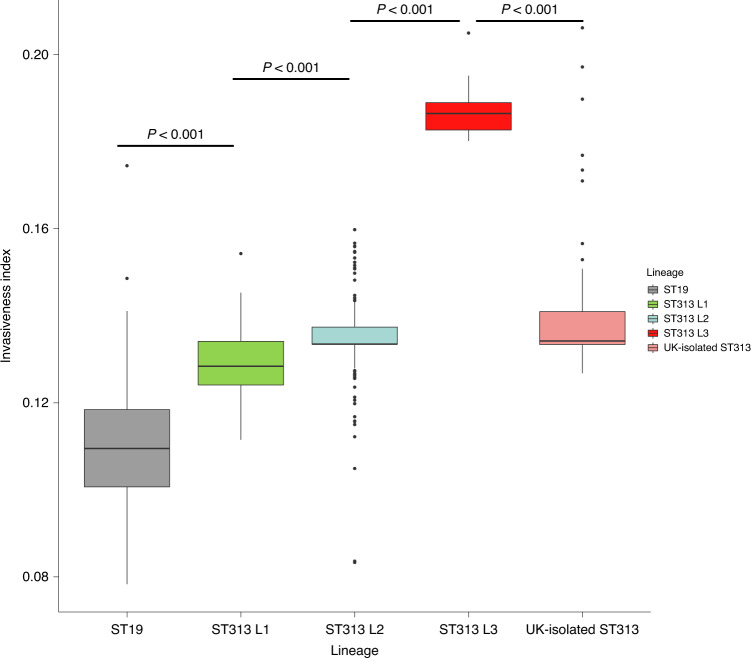

To determine the potential of ST313 L3 to cause BSI, the invasiveness index of each sample was calculated and compared between different ST313 lineages using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test46. The ‘invasiveness index’ represents the extent of genome degradation and diversifying selection specific to invasive serovars, using a proven set of 196 extraintestinal predictor genes47. Consistent with previous studies, we observed a significant increase in the invasiveness index of ST313 L2 compared with ST313 L1 (W = 7,636.5, P < 0.001), and ST313 L1 compared with ST19 (W = 552.5, P < 0.001)11,47. ST313 L3 had a particularly high invasiveness index (median = 0.187, s.d. = 0.008), which was significantly greater than that of ST19 (median = 0.110, s.d. = 0.017), ST313 L1 (median = 0.129, s.d. = 0.008) or ST313 L2 (median = 0.134, s.d. = 0.006) (W = 0, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). ST313 L3 also had a significantly greater invasiveness index than the UK-isolated ST313 (median = 0.134, s.d. = 0.018), (W = 480, P < 0.001).

Fig. 5. Invasiveness index of ST19 and ST313 lineages.

Box plot representing the distribution of invasiveness index values for all genome sequences included in this study summarized by lineage assignment. UK-isolated ST313 refers to those described in ref. 7. Groups were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test46 and the resultant P-values were all less than 0.001. Number of isolates in each group: ST19 (n = 66), ST313 L1 (n = 52), ST313 L2 (n = 550), ST313 L3 (n = 9) and UK-isolated ST313 (n = 59). In the box plot, centre lines represent median values, box limits represent upper and lower quartiles, whiskers represent 1.5× the interquartile range and individual points represent outliers. The box plot was created using R ggplot288.

In total, 17 of the 196 extraintestinal predictor genes had undergone additional degradation in ST313 L3 (isolate BKQZM9) compared with ST313 L2 (D23580), involving the presence of non-synonymous SNPs, indels or gene loss (Supplementary Table 5). A number of the degraded genes in ST313 L3 are required for colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract by S. Typhimurium ST19, including mrcB, a gene that allows Salmonella Typhi to survive in the presence of bile48. In S. Typhimurium, a functional damX gene is required for resistance to bile49, and was degraded in seven of the nine ST313 L3 isolates. The napA gene had extensive deletions in all but one of the ST313 L3 isolates, and encodes a periplasmic nitrate reductase required for gut colonisation17,50. Together, our findings suggest that ST313 L3 is in the process of adapting from an intestinal to a systemic lifestyle.

Clearly, this in silico approach does not prove that ST313 L3 has adapted to an extraintestinal lifestyle. In the past, infection models have provided understanding of the virulence and systemic spread of Salmonella pathovariants that cause gastroenteritis51. However, cellular and animal infection models have failed to discriminate between levels of invasiveness of ST313 L1 and L214 and an ST313 sublineage identified in the Democratic Republic of Congo11. Although the invasiveness index cannot yet be experimentally validated, Salmonella isolates with different invasiveness indices produce distinct clinical symptoms in a human population52. The development and validation of experimental approaches for the robust measurement of the invasiveness of African S. Typhimurium will be an important focus for future research, but goes beyond the scope of this paper. Meanwhile, the ‘invasiveness index’ is a useful tool for monitoring the genetic signatures associated with invasiveness and host adaptation in ST313 lineages.

Perspective

Our data provide an expanded and contemporary insight into the dynamics of S. Typhimurium-associated BSI in Africa, elucidating the stepwise evolution of ST313. This study provides a snapshot of the large repertoire of genomic changes that shaped the emergence of successful ST313 lineages. The stepwise pseudogenization of genes reported here is consistent with the host adaptation of S. Typhimurium ST313 lineages over evolutionary history6,40 and supports mounting evidence for a human ST313 reservoir40. Our findings reflect similar patterns of evolution found in other Salmonella serovars that currently cause BSI disease globally. For example, a third of all iNTS disease cases in Africa are caused by S. Enteritidis which also shows signs of genome degradation consistent with niche adaptation30,53.

We discovered that ST313 L3 emerged in 2016 as a cause of BSI in the Malawian population, and had an MRCA from around ad 2007. It is possible that the phased removal of chloramphenicol from clinical practice following local policy changes in Malawi between 2002 and 2005 created a window of opportunity for the emergence of fully susceptible ST313 L3 (Supplementary Discussion 2). ST313 L3 forms a monophyletic cluster within a diverse group of ST313 originally identified in the UK7. The combination of our phylogenetic and accessory genome analyses led us to conclude that ST313 L3 has been introduced into the Malawian population, probably via an international transmission event. Importantly, ST313 L3 had an elevated invasiveness index compared to ST313 L2, unlike the UK-isolated ST313 strains that had a lower invasiveness index than ST313 L247. The majority of genes unique to ST313 L3 were plasmid- or prophage-encoded, including by the prophage RE-201029 which is found in other extraintestinal Salmonella pathovariants30–32. Apart from accessory genome composition, other ST313 L3-specific changes involve loss-of-function SNPs in genes that are not required for systemic infection. The findings predict that ST313 L3 will be better adapted to cause extraintestinal infection than other ST313 lineages from both the UK and Malawi, possibly explaining the emergence of ST313 L3.

Methods

Dataset

Salmonella samples were derived from two archived blood culture collections. The main dataset was sourced from the MLW in Blantyre, Malawi and consists of over 14,000 Salmonella bloodstream isolates from patients with iNTS disease at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital between 1996 and 2018. Isolates listed as S. Typhimurium were extracted from the metadata file for the entire collection and stratified by AMR profile into the following four categories: susceptible, resistant to one first-line agent, resistant to two first-line agents, or MDR. First-line agents were considered to be ampicillin, cotrimoxazole and chloramphenicol. Random subsampling was then performed using a random number generator (Excel, Microsoft) and selected samples were collected and resuscitated from the freezer archives at MLW. We successfully recovered 647 isolates for whole-genome sequencing.

To complete the MLW data, a contextual dataset was sourced from the Institut Pasteur, Paris. The dataset consisted of 96 S. Typhimurium isolates collected from human extraintestinal sites from patients contaminated in Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, France, Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Sudan, Togo and Vietnam between 1966 and 2012. All 96 S. Typhimurium samples were selected and sent for whole-genome sequencing.

Whole-genome sequencing of short reads

Isolates were prepared by inoculating a single bead of frozen Salmonella stock into a FluidX 2D Sequencing Tube (FluidX) containing 100 μl buffered peptone water (Oxoid, CM0509) and incubating overnight at 37 °C. Thermolysates were generated by heat-killing cultures in a 95 °C water bath for 20 min before DNA extraction (MagAttract kit, Qiagen) and whole-genome sequencing, as part of the 10,000 Salmonella Genomes Project54 (https://10k-salmonella-genomes.com/). Illumina Nextera XT DNA Libraries were prepared (Illumina, FC-131-1096) and sequenced (Illumina HiSeq 4000) in multiplex (768) as 150-bp paired-end reads.

Assembly and annotation of short reads

Trimmomatic55 v0.36 was used to trim adapters and Seqtk v1.2-r94 (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk) was used to trim low-quality regions using the trimfq flag. Fastqc v0.11.5 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and multiqc v1.0 (http://multiqc.info) were used to pass sequence reads according to the following criteria: passed basic quality statistics, per base sequence quality, per base N content, adapter content and an average GC content of between 47% and 57%. Only high-quality reads were used in downstream analysis. Unicycler56 v0.3.0 was used to assemble genomes and QUAST57 v4.6.3 was used to evaluate assembly quality to standards consistent with Enterobase58. Specifically, N50 > 20 kb, 600 or fewer contiguous sequences, total number of bases between 4 Mbp and 5.8 Mbp. Prokka59 v1.12 was used to annotate the genomes.

Sequence typing

Serotyping was confirmed using the Salmonella In Silico Typing Resource60 v1.0.2 and compared with the original metadata table. The strains were assigned a multi-locus sequence type (MLST) using MLST61 v2.10 on the basis of the conservation of seven housekeeping genes.

Reference mapping to D23580

Trimmed sequencing data were mapped against the S. Typhimurium reference genome D23580 using BWA mem62 v0.7.10-r789. The reference genome consists of the D23550 chromosome (GenBank accession: LS997973.1), and four plasmids including pSLT-BT (accession: LS997974.1), pBT1 (accession: LS997975.1), pBT2 (accession: LS997976.1) and pBT3 (accession: LS997977.1). Mapped reads were then cleaned and sorted using the SAMtools suite63 v1.7. Reads were realigned against the reference using GATK64 v3.7 by creating targets for realignment (RealignerTargetCreator) and performing realignment (IndelRealigner). Removal of optical duplicates was completed using Picard v2.10.1-SNAPSHOT (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Sequence variants were called using Bcftools v1.9-80 (http://samtools.github.io/bcftools) to generate a reference-based pseudogenome for each sample with greater than 10× depth. QualiMap65 v2.0 was used to identify a mean sample depth of 35.17× across all isolates.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of dataset

High-quality pseudogenomes (MLW n = 608, contextual n = 72) were concatenated, plasmids were excluded and Gubbins66 v2.2 was used to remove recombinant regions and invariable sites. The resultant multiple sequence alignment of reference-based pseudogenomes (12,013 variant sites) was used to infer a maximum-likelihood phylogeny using RAxML-ng67 v0.6.0 with 100 bootstrap replicates to assess support. To assign clusters, rhierBAPs68 was used, specifying two cluster levels, 20 initial clusters and infinite extra rounds. Visualizations were performed using interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL)69 v4.2.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of dataset and publicly available dataset

For contextual interpretation, previously published S. Typhimurium ST313 sequences were retrieved from public repositories (Supplementary Table 2) and constructed in a core gene phylogeny with our data. Roary70 v3.11.0 was used to generate a core gene alignment and SNP-sites71 v2.3.3 was used to extract SNPs. The resultant multiple sequence alignment (15,240 variant sites) was used to construct a maximum-likelihood phylogeny using RAxML-ng67 v0.6.0 with 100 bootstrap replicates to assess branch support. Visualizations were made using iTOL69 v4.2.

Temporal phylogenetic reconstruction

To determine the evolutionary history of ST313, a chronogram was produced using Bayesian phylogenetic inference. Because the MLW collection is substantially larger than the contextual collection and to reduce computation time, 150/680 samples were chosen for inclusion in the analysis as described below. Sampling reflected original sample selection for this study and included all contextual isolates which passed quality control (n = 72) and a subset of MLW isolates randomly selected using a random number generator (n = 78, Microsoft Excel). A reference-mapped multiple sequence alignment (7,231 variant sites) was created as described above. BEAUTI72 v2.6.1 and BEAST272 v2.6.1 were used to create and execute three independent chains of length 250,000,000 with 10% burn in, logging every 1,000 and accounting for invariant sites. We included the prior assumptions of a coalescent Bayesian skyline model for population growth, and a relaxed log normal clock rate to account for rate heterogeneity amongst branches (the full model is described in Supplementary Data 1). Tracer73 v1.7.1 was used to assess convergence, with all parameter effective sampling sizes being >200. LogCombiner72 v2.6.1 was used to combine tree files and DensiTree v2.2.774 was used for visualization. Finally, a maximum clade credibility tree was created using TreeAnnotator72 v2.6.0.

Determination of invasiveness index

The invasiveness index of each isolate was calculated using previously defined methods47. Because isolates used in our study originated from human bloodstream, we used an invasiveness index model that was pre-trained using a mixture of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal salmonellae47. Specifically, samples were analysed using 196 top predictor genes for measuring invasiveness in S. enterica. The machine-learning approach uses a random forest classifier and delta-bitscore functional variant-calling to discriminate between the genomes of invasive and gastrointestinal Salmonella. The invasiveness index has been validated using multiple Salmonella serovars, and the approach clearly discriminated between the S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium lineages associated with extraintestinal infections in sub-Saharan Africa11,47. The distribution of invasiveness index values for each lineage were compared using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test46 implemented through R75 v3.4.0. A custom-made database of the top 196 invasiveness predictor genes was then created from the multi-fasta file provided47. SRST276 v0.2.0 was used to flag any genes with mutations in ST313 L3 compared with ST313 L2. Exact mutations were investigated manually using MegaX77 v0.1.

AMR testing and statistical analysis

Genetic determinants for AMR were identified using staramr v0.5.1 (https://github.com/phac-nml/staramr) against the ResFinder78 and PointFinder79 databases. Phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the EUCAST disk diffusion method80 (Antibiotic discs: ampicillin 10 μg, chloramphenicol 30 μg and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 25 μg from Mast Group). To compare the results of genotypic against phenotypic testing, sensitivity and specificity were calculated for first-line agents used over the study period using MedCalc’s test evaluation calculator with Clopper–Pearson confidence intervals (https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php).

Genomic conservation of plasmids, prophages and pseudogenes

A literature search was used to identify genomic regions known to vary between ST19 and ST313, including plasmids5, prophages33 and pseudogenes7,13–17,43,81,82. We compiled a list of previously identified pseudogenes associated with the emergence of ST313 lineages in Africa (Supplementary Table 4)14. The collection included metabolic genes (melR17 and ttdA14), environmentally responsive genes (bcsG15, katE15 and macB13), genes that modulate the bacterial cell surface (flhA17 and lpxO83) and virulence genes (pipD43, ratB14, sseI16). Genes of unknown function were not included. We detected the SNPs responsible for pseudogene formation, as well as other non-synonymous mutations. A custom-made database of the identified regions was created, along with known variants. Sequences were downloaded using the online tool SalComD2358017. SRST276 v0.2.0 was then used to identify alleles present and the non-exact matches were investigated manually using MegaX77 v0.1. Prophage and plasmid presence or absence were manually mapped onto the phylogeny using iTOL69 v4.2. The conservation of pseudogene-associated mutations was identified at the population level and integrated into the temporal phylogenetic reconstruction using iTOL69 v4.2. These analyses allowed inference of branches in which functional gene loss and plasmid and prophage acquisition occurred. Phenotypic testing was conducted to determine the relevance of plasmid and functional gene loss as detailed in Supplementary Methods 1.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of pSLT plasmid

Plasmid sequences were extracted from high-quality pseudogenomes and snp-sites71 was used to extract SNPs. The resultant multiple sequence alignment of length 1,034 sites was used to infer a maximum-likelihood phylogeny using RAxML-ng67 v0.6.0 with 100 bootstrap replicates to assess support. The phylogeny was visualized in iTOL69 and convenience rooted to display lineages.

Long-read sequencing of ST313 L3 reference strain BKQZM9

ST313 L3 strain BKQZM9 was selected for long-read sequencing as it has the highest overall quality statistics based on short-read sequencing. An Oxford Nanopore MinION84 9.4.1 flowcell and SQK-RAD004 rapid sequencing kit was used with base calling by Guppy v3.1.5 (https://nanoporetech.com/nanopore-sequencing-data-analysis#). Approximately 120× coverage (600 Mb, 60,164 reads, read N50 33 kb) was generated. Hybrid genome assembly with the Illumina reads was done using Unicycler56 v0.4.4 which resulted in a 4.8-Mb circular polished chromosome (GenBank accession: CP060169), a 94-kb circular plasmid (pSLT) (accession CP060170) and a 1,975-bp circular plasmid (pBT3) (accession: CP060171). Prokka59 v1.12 was used for annotation as above.

Genomic comparison of ST313 lineages

To determine the basic architecture of the ST313 L3 BKQZM9 genome, the identity of the chromosomal and plasmid regions were compared with existing sequences from ST313 L1 (A130), ST313 L2 (D23580) and ST313 UK (U2) using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)85 and visualized using the Artemis Comparison Tool86 v13.0.0. Putative prophage and plasmid sequences were extracted and identified using a BLAST85 search against known ST313 prophages and plasmids and the non-redundant NCBI nucleotide database. Prophage and plasmid presence or absence were also determined experimentally (Supplementary Discussion 2).

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Discussions 1 and 2, and Supplementary Methods.

Contains the following supplementary tables: Supplementary Table 1: Quality control statistics; Supplementary Table 2: Metadata and accession numbers; Supplementary Table 3: Contextual metadata and accession numbers; and Supplementary Table 5: Mutations in top predictor genes for invasiveness.

BEAST xml file.

Acknowledgements

We thank present and former members of Lab H at the Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool, including members of the Hinton and Baker groups for invaluable discussions, in particular C. Chong, M. Horsburgh, S. Owen and K. Costigan for their support, contributions and advice; the MLW clinical research programme and the Institute Pasteur for access to their Salmonella archives; P. Ashton for helpful comments on the manuscript; and R. Low for his assistance in uploading metadata to repositories. C.V.P. is supported by the John Lennon Memorial Scholarship from the University of Liverpool and a Fee Bursary Award from the Institute of Integrative Biology at the University of Liverpool. B.K. was funded by an AESA-RISE fellowship from the African Academy of Sciences. N.H. is funded by the BBSRC, Core Strategic Programme Grant at the Earlham Institute (BB/CSP17270/1). F.-X.W. and A.T.-D. are supported by the Institut Pasteur, Santé publique and the French government’s Investissement d’Avenir programme, Laboratoire d’Excellence ‘Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases’ (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID). K.S.B. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Career Development Fellowship (106690/A/14/Z). J.C.D.H. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (106914/Z/15/Z). Genome sequencing was done by the Earlham Institute as part of the 10,000 Salmonella genomes project which is supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund data and resources grant (BBS/OS/GC/000009D). Next-generation sequencing and library construction were delivered via the BBSRC National Capability in Genomics and Single Cell (BB/CCG1720/1) at Earlham Institute, by members of the Genomics Pipelines Group.

Extended data

Author contributions

C.V.P. was involved in conceptualizing and designing the overall study and performed the majority of phylogenetic, genomic and statistical analyses. B.M.P.-S. was involved in conceptualizing, designing and performing phenotypic characterization of isolates. R.C. contributed to conceptualization of pseudogene analysis and constructed S. Typhimurium 4/74 ΔlpxO::aph mutant for mass spectrometry analysis by λ red recombineering. R.P., H.C.B., L.A., M.P.M. and A.B.-B. assisted in collection of isolates from MLW Clinical Research Center. A.T.-D. assisted in the collection of isolates from Institut Pasteur. R.J. Bengtsson and W.M.P.R. contributed phylogenetic and genomic analysis and supported troubleshooting. R.J. Bennett and G.E.S. contributed to BEAST analysis and bioinformatic troubleshooting. A.Y.B., A.V.P. and A.C.D. completed long-read sequencing and assembly of ST313 L3 reference strain BKQZM9. B.K. contributed to analysis of contemporary whole-genome sequences. J.A. Bevington performed phenotypic characterization of AMR profiles. N.W. performed phenotypic characterization of the pAnkS encoded LsoA–LsoB toxin–antitoxin proteins. J.A. Bengoechea and A.D. did lipid A analysis by mass spectrometry. E.V.R. performed phenotypic confirmation of plasmid and prophage repertoire. H.J.W. and X.Z. performed phenotypic characterization of isolates. P.M.D.S. provided support in reviewing and interpreting results. N.H. sequenced isolates as part of the 10,000 Salmonella genomes project. F.-X.W., M.A.G., N.A.F., K.S.B. and J.C.D.H. were involved in conceptualizing and designing the overall study. K.S.B. and J.C.D.H. additionally supervised the entire study.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). Accession numbers are available in Supplementary Table 2. The complete genome and plasmid sequence for ST313 L3 strain BKQZM9 can be found under bioproject ID PRJNA656707, specifically, complete chromosome (GenBank accession: CP060169), pSLT (GenBank Accession: CP060170) and pBT3 (GenBank Accession: CP060171). The following three S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are in the process of being deposited in the DSMZ strain collection: A130 (ST313 L1), D23580 (ST313 L2) and BKQZM9 (ST313 L3). Publicly available sequence data were downloaded from one of the following sources: GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra), European Nucleotide Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) or Enterobase (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk). Accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The data summarized in Extended Data Fig. 2 are available in Supplementary Table 3. The remaining relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

Competing interests

R.C. was employed by the University of Liverpool at the time of the study and is now an employee of the GSK group of companies. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Microbiology thanks Gordon Dougan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41564-020-00836-1.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41564-020-00836-1.

References

- 1.Stanaway JD, et al. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019;19:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet. 2012;379:2489–2499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchello CS, Dale AP, Pisharody S, Rubach MP, Crump JA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of community-onset bloodstream infections among hospitalized patients in Africa and Asia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;64:e01974–19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01974-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy EA, Shaw AV, Crump JA. Community-acquired bloodstream infections in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010;10:417–432. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kingsley RA, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 2009;19:2279–2287. doi: 10.1101/gr.091017.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okoro CK, et al. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1215–1221. doi: 10.1038/ng.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashton PM, et al. Public health surveillance in the UK revolutionises our understanding of the invasive Salmonella Typhimurium epidemic in Africa. Genome Med. 2017;9:92. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almeida F, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Salmonella Typhimurium reveals the presence of the highly invasive ST313 in Brazil. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017;51:41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feasey NA, et al. Three epidemics of invasive multidrug-resistant Salmonella bloodstream infection in Blantyre, Malawi, 1998–2014. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;61:S363–S371. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feasey NA, et al. Drug resistance in Salmonella enterica ser. Typhimurium bloodstream infection, Malawi. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1957–1959. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.141175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Puyvelde S, et al. An African Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 sublineage with extensive drug resistance and signatures of host adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4280. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11844-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccini G, Montomoli E. Pathogenic signature of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella in Africa: implications for vaccine development. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020;16:2056–2071. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1785791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogomolnaya, L. M. et al. The ABC-type efflux pump MacAB protects Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from oxidative stress. mBio4, e00630-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Okoro CK, et al. Signatures of adaptation in human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 populations from sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singletary LA, et al. Loss of multicellular behavior in epidemic African nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ST313 strain D23580. mBio. 2016;7:e02265. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02265-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carden SE, et al. Pseudogenization of the secreted effector gene sseI confers rapid systemic dissemination of S. Typhimurium ST313 within migratory dendritic cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:182–194. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canals R, et al. Adding function to the genome of African Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 strain D23580. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honeycutt JD, et al. Genetic variation in the MacAB–TolC efflux pump influences pathogenesis of invasive Salmonella isolates from Africa. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008763. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aulicino A, et al. Invasive Salmonella exploits divergent immune evasion strategies in infected and bystander dendritic cell subsets. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4883. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07329-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashton, P. et al. Revolutionising public health reference microbiology using whole genome sequencing: Salmonella as an exemplar. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/033225 (2015).

- 21.Jacob JJ, et al. Genomic analysis of human invasive Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ST313 isolate B3589 from India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;73:416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran-Dien A, Le Hello S, Bouchier C, Weill F-X. Early transmissible ampicillin resistance in zoonotic Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in the late 1950s: a retrospective, whole-genome sequencing study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30705-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagambega A, Lienemann T, Frye JG, Barro N, Haukka K. Whole genome sequencing of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolated from humans and poultry in Burkina Faso. Trop. Med. Health. 2018;46:4. doi: 10.1186/s41182-018-0086-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotger R, Casadesus J. The virulence plasmids of Salmonella. Int. Microbiol. 1999;2:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahin F, Karasartova D, Gerceker D, Aysev AD, Erdem B. A novel Salmonella Typhimurium plasmid, pAnkS: an example for plasmid evolution in antibiotic resistance. Mikrobiyol. Bul. 2008;42:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otsuka Y, Yonesaki T. Dmd of bacteriophage T4 functions as an antitoxin against Escherichia coli LsoA and RnlA toxins. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;83:669–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueroa-Bossi N, Uzzau S, Maloriol D, Bossi L. Variable assortment of prophages provides a transferable repertoire of pathogenic determinants in Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:260–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker CP, Heuzenroeder MW. ST64B is a defective bacteriophage in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT64 that encodes a functional immunity region capable of mediating phage-type conversion. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;294:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna LF, Matthews TD, Dinsdale EA, Hasty D, Edwards RA. Characterization of the ELPhiS prophage from Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis strain LK5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:1785–1793. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07241-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feasey NA, et al. Distinct Salmonella Enteritidis lineages associated with enterocolitis in high-income settings and invasive disease in low-income settings. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/ng.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pulford CV, et al. Salmonella enterica serovar Panama, an understudied serovar responsible for extraintestinal salmonellosis worldwide. Infect. Immun. 2019;87:e00273–19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00273-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao K, et al. Complete genome and methylome sequences of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Panama (ATCC 7378) and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Sloterdijk (ATCC 15791). Genome Announc. 2016;4:e00133–16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00133-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen SV, et al. Characterization of the prophage repertoire of African Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 reveals high levels of spontaneous induction of novel phage BTP1. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:235. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owen, S. V. et al. Prophage-encoded phage defence proteins with cognate self-immunity. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/2020.07.13.199331 (2020).

- 35.Susskind MM, Wright A, Botstein D. Superinfection exclusion by P22 prophage in lysogens of Salmonellatyphimurium: IV. Genetics and physiology of sieB exclusion. Virology. 1974;62:367–384. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magiorakos A-P, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooper DC, Jacoby GA. Mechanisms of drug resistance: quinolone resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015;1354:12–31. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma M, Eaton JW. Multicellular oxidant defense in unicellular organisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7924–7928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacKenzie KD, et al. Parallel evolution leading to impaired biofilm formation in invasive Salmonella strains. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Post AS, et al. Supporting evidence for a human reservoir of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella from household samples in Burkina Faso. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019;13:e0007782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crump, J. A. et al. Investigating the meat pathway as a source of human nontyphoidal Salmonella bloodstream infections and diarrhea in East Africa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1153 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Nguyen BD, et al. Import of aspartate and malate by DcuABC drives H2/fumarate respiration to promote initial Salmonella gut-lumen colonization in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:922–936. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawley TD, et al. Genome-wide screen for salmonella genes required for long-term systemic infection of the mouse. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood MW, et al. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella enteropathogenicity. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:883–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreira CG, et al. Virulence and stress-related periplasmic protein (VisP) in bacterial/host associations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1470–1475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215416110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKnight, P. E. & Najab, J. in The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology (eds Weiner, I. B. & Craighead, W. E.) (Wiley, 2010).

- 47.Wheeler NE, Gardner PP, Barquist L. Machine learning identifies signatures of host adaptation in the bacterial pathogen Salmonella enterica. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langridge GC, et al. Simultaneous assay of every Salmonella Typhi gene using one million transposon mutants. Genome Res. 2009;19:2308–2316. doi: 10.1101/gr.097097.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez-Garrido J, Cheng N, Garcia-Quintanilla F, Garcia-del Portillo F, Casadesus J. Identification of the Salmonella enterica damX gene product, an inner membrane protein involved in bile resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:893–895. doi: 10.1128/JB.01220-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez CA, Rivera-Chavez F, Byndloss MX, Baumler AJ. The periplasmic nitrate reductase NapABC supports luminal growth of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium during colitis. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:3470–3478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00351-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsolis RM, Xavier MN, Santos RL, Bäumler AJ. How to become a top model: impact of animal experimentation on human Salmonella disease research. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:1806–1814. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01369-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tack B, Vanaenrode J, Verbakel JY, Toelen J, Jacobs J. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review on antimicrobial resistance and treatment. BMC Med. 2020;18:212. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01652-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langridge GC, et al. Patterns of genome evolution that have accompanied host adaptation in Salmonella. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:863–868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416707112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Sepulveda, B. M. et al. An accessible, efficient and global approach for the large-scale sequencing of bacterial genomes. Preprint at bioRxiv (2020). 10.1101/2020.07.22.200840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alikhan N-F, Zhou Z, Sergeant MJ, Achtman M. A genomic overview of the population structure of Salmonella. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshida CE, et al. The Salmonella In Silico Typing Resource (SISTR): an open web-accessible tool for rapidly typing and subtyping draft salmonella genome assemblies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larsen MV, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.García-Alcalde F, et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2678–2679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:e15–e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tonkin-Hill G, Lees JA, Bentley SD, Frost SDW, Corander J. RhierBAPS: An R implementation of the population clustering algorithm hierBAPS. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:93. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14694.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Page AJ, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Page AJ, et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb. Genom. 2016;2:e000056. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bouckaert R, et al. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019;15:e1006650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018;67:901–904. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bouckaert RR. DensiTree: making sense of sets of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1372–1373. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017).

- 76.Inouye M, et al. SRST2: Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med. 2014;6:90. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zankari E, et al. PointFinder: a novel web tool for WGS-based detection of antimicrobial resistance associated with chromosomal point mutations in bacterial pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017;72:2764–2768. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matuschek E, Brown DFJ, Kahlmeter G. Development of the EUCAST disk diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility testing method and its implementation in routine microbiology laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:O255–O266. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nishino K, Latifi T, Groisman EA. Virulence and drug resistance roles of multidrug efflux systems of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:126–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang J, et al. Characterization of the invasive, multidrug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella strain D23580 in a murine model of infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gibbons HS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. Oxygen requirement for the biosynthesis of the S-2-hydroxymyristate moiety in Salmonellatyphimurium lipid A. Function of LpxO, a new Fe2+/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32940–32949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jain M, Olsen HE, Paten B, Akeson M. The Oxford Nanopore MinION: delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biol. 2016;17:239. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1103-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carver TJ, et al. ACT: the Artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3422–3423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2938–2940. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag, 2016).

- 89.Msefula CL, et al. Genotypic homogeneity of multidrug resistant S. Typhimurium infecting distinct adult and childhood susceptibility groups in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Discussions 1 and 2, and Supplementary Methods.

Contains the following supplementary tables: Supplementary Table 1: Quality control statistics; Supplementary Table 2: Metadata and accession numbers; Supplementary Table 3: Contextual metadata and accession numbers; and Supplementary Table 5: Mutations in top predictor genes for invasiveness.

BEAST xml file.

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). Accession numbers are available in Supplementary Table 2. The complete genome and plasmid sequence for ST313 L3 strain BKQZM9 can be found under bioproject ID PRJNA656707, specifically, complete chromosome (GenBank accession: CP060169), pSLT (GenBank Accession: CP060170) and pBT3 (GenBank Accession: CP060171). The following three S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are in the process of being deposited in the DSMZ strain collection: A130 (ST313 L1), D23580 (ST313 L2) and BKQZM9 (ST313 L3). Publicly available sequence data were downloaded from one of the following sources: GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra), European Nucleotide Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) or Enterobase (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk). Accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The data summarized in Extended Data Fig. 2 are available in Supplementary Table 3. The remaining relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.